Sarracenia flava, from Mark Catesby, 1754.

Man has been aware of carnivorous plants for centuries, though their feeding habits weren’t categorically confirmed until Charles Darwin wrote Insectivorous Plants, published in 1875. In Henry Lyte’s New Herball of 1578, the widespread sundew species Drosera rotundifolia is pictured and described, albeit somewhat erroneously in the chapter describing mosses, despite the recognition of it possessing white flowers.

This herb is of a very strange nature and marvellous: for although that the sun does shine hot, and a long time thereon, yet you shall find it always moist and bedewed, and the hairs thereof always full of little drops of water: and the hotter the sun shineth upon this herb, so much the moistier it is and the more bedewed, and for that cause it was called Ros Solis in Latin, which is to say in English, The Dew of the Sun, or Sun Dew.

A charming description of what was recognized then as a somewhat unusual plant—but no mention of its carnivorous habit, nor any clue that Lyte noticed a presence of insects caught on the leaves in his observation of the plant.

Early references to Sarracenia also do not take into account the genus’s potential carnivorous habit. The botanist Mark Catesby in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, published in 1754, illustrates both S. flava and S. purpurea, and even goes so far as to state of S. purpurea that the leaves contain water and that they seem “to serve as an asylum or secure retreat for numerous insects, from frogs and other animals which feed on them.”

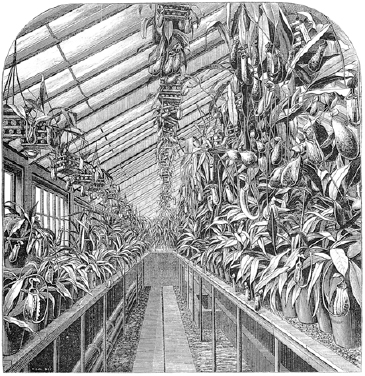

Sarracenia flava, from Mark Catesby, 1754.

Drosera rotundifolia as illustrated in Henry Lyte’s New Herball, 1578.

The first suggestion that these plants may have evolved elaborate traps to catch insects was made in the 1760s when the Venus flytrap was dubbed the “fly trap sensitive” by Arthur Dobbs, governor of North Carolina at the time. But the notion that the plant was deriving some nutritional benefit wasn’t mentioned until 1770, when the plant was formally described as Dionaea muscipula by John Ellis, a textile merchant and naturalist. In his description, he states that “nature may have some view toward its nourishment, informing the upper joint of its leaf like a machine to catch food.”

This view wasn’t widely accepted. At a time when all aspects of nature were considered to be God’s work, the notion that a plant could devour animals was quickly dismissed, even by the great Carl Linnaeus, with whom Ellis had corresponded.

Ellis’s illustration of the Venus flytrap, 1770.

For the next century, the notion of plant carnivory was kicked to the long grass to languish alongside other absurd notions of the day. However, the discovery of new species (such as the gargantuan pitcher plant Nepenthes rajah on the island of Borneo) rekindled interest, and it was then that Darwin embraced the genre. In 1859 he had published his Origin of Species, striking the first fracturing blow to the established views of nature and its place in the world. The book’s reception had at first been hostile, but since he was an established and respected scientist, his peers couldn’t completely dismiss his ideas. Who better to tackle the delicate subject of carnivorous plants? Insectivorous Plants was the first detailed study on the topic, with much of the volume concentrating on his study of the sundew Drosera rotundifolia, but he also examined and included a number of other genera.

On the basis of his studies, Darwin concluded, “There is a class of plants which digest and afterward absorb animal matter.” Well, it couldn’t be clearer than that, and Darwin himself proclaimed, “I care more about Drosera than the origin of all the species.”

The discovery of a huge number of carnivorous plants from around the world fuelled a frenzy of plant collecting during the Victorian era, and large collections were amassed by those with the necessary wealth to both obtain and maintain them. Nurseries such as the famous Veitch of Chelsea, which also traded in Exeter, introduced hundreds of new exotic species to cultivation, even having a dedicated Nepenthes house.

This time of plenty for the fortunate few came crashing down, however, with the start of the First World War, and the amassed plant collections were lost as maintenance costs soared and interest in caring for the plants waned. Interestingly, the Chelsea Veitch nursery ceased trading in 1914, while its Exeter branch continued to operate. Most of the privately held collections were lost, and serious interest in carnivorous plants wasn’t rekindled for decades.

The next great work on the subject came in 1942, with the publication of Francis E. Lloyd’s The Carnivorous Plants, which concentrated on taxonomy rather than cultivation. Continuing the work of Darwin and more obscure studies completed in the intervening period, Lloyd’s work is still regarded as relevant today, and helped bring the plants back into the limelight. A small number of individuals formed the International Carnivorous Plant Society in 1972, and that combined with Adrian Slack’s book in 1979 gave the hobby a shaky rebirth.

A nineteenth-century illustration of the Veitch nursery Nepenthes house.

WHERE ARE THEY FOUND? TROPICAL VS. TEMPERATE

Carnivorous plants enjoy worldwide distribution. Across the temperate regions of Asia, Europe, North America, and other similar climates, they are typically bog plants, inhabiting wet, peaty areas—environments which certainly in Europe and North America have been greatly reduced due to land drainage and peat extraction. Peat is formed very slowly by the decaying of vegetable matter, predominantly sphagnum moss. The process is lengthy because of the absence of oxygen, due to the waterlogged ground conditions. It is this slow formation that leads peat to be generally considered non-renewable, forming at the rate of around 1/25 in. (1 mm) per year.

Settings such as these are generally open areas, acidic and very low in nutrients; typical vegetation includes grasses and sedges, mosses, and their most unusual residents, carnivorous plants. Which leads to the fundamental question about our subject matter: Why are these plants capable of consuming creatures for sustenance?

As in so many cases, where there is a need, nature provides a solution. Boggy areas are so limited in nutrients (especially nitrogen and phosphorous) that over many millennia, some of the plants in these environments adapted to catch and digest animals to supplement the meagre diet provided by the conditions. The ability to digest mostly insects affords the plants an advantage over their non-carnivorous neighbours.

A sphagnum bog in Southern England. The red-coloured plants are the English sundew, Drosera anglica.

In other areas of the world, the habitats in which carnivorous plants are found vary from those in temperate regions. In countries such as Australia, South Africa, and Mexico, habitats can be only seasonally wet and then dry part of the year. This presents a challenge for the plants since a good amount of water is required during their active carnivorous phase. Certainly in the genus Drosera there are some interesting environmental adaptations to surviving the arid season; a couple of droseras are annual—which means they germinate, grow, flower, and ultimately produce seed in a single season before dying. The seeds lie on the ground until the rains return, when the cycle repeats. The majority of carnivorous plants, however, employ additional tactics to survive. Some produce long, thick, fleshy roots which penetrate deep into the soil, where they retreat to survive the dry season. One group of Australian sundews goes a stage further, producing an underground tuber each year.

The Portuguese dewy pine, Drosophyllum lusitanicum, an unusual sticky-leaved plant which is found in coastal Portugal, southern Spain, and northern Morocco, grows mainly on arid slopes where summers are hot and dry, and winter temperatures can drop to freezing. Again, a substantial and expansive rootstock sustains the plant in its harsh environment.

A large specimen of Drosophyllum lusitanicum.

Then there are the stereotypical tropical environments that most people assume are the natural habitats of all carnivorous plants. In reality, only a handful of genera call the lowland tropics home. The rainforest evokes images of hot, steamy jungles, dense with vegetation, inhabited by leeches and other creatures ready and waiting to bite the unwary visitor. This environment (hot and humid year-round) is found at low altitude, and comparatively few carnivorous plants grow here—a few species of the tropical pitcher plant (Nepenthes) in Southeast Asia, and some bladderwort species (Utricularia), but not many other than those.

Perhaps surprisingly, looking a bit higher in altitude, where conditions are not only humid but cooler, one finds many additional species, including the majority of those in the genus Nepenthes. While there are currently around 150 species of Nepenthes, the total is increasing all the time, as botanically unexplored mountains are conquered and their green treasures discovered. In this habitat, trees are festooned with mosses, epiphytic plants such as orchids, and in some cases carnivorous bladderworts, which cling to branches.

So, generally speaking, native habitats can be roughly divided into tropical or temperate. For ease, let’s assume the plants I’ve just mentioned fall into the former, and all others, the latter. Temperate dwellers fill the other ecological niches and contain among their number those most likely to be cultivated successfully in Europe and the United States.

Now, I’m not saying that everything other than the tropical species can be grown together, or outside, but with a little consideration to requirements, you will be surprised what you can actually grow at home.

WHAT DO THEY EAT, AND CAN THEY BE USED AS INSECT CONTROL?

It could be argued that the term “carnivorous” is something of a misnomer. It would probably be more apt to refer to carnivorous plants as insectivorous, as the bulk of these plants’ diet is made up of insects. There are exceptions, however—in some cases, quite extraordinary ones.

Defining carnivorous

To begin, one must consider the attributes necessary for a plant to be classified as carnivorous. The following are all necessary criteria.

AN ATTRACTION, SOMETHING THAT ENTICES INSECTS TO THE PLANT. This is usually in the form of sugar-laden nectar, produced in copious amounts by sarracenias and other pitcher plants. Nectar is also sometimes used in conjunction with ultraviolet patterning, which renders leaves highly visible to insects.

A METHOD BY WHICH THE PLANT CATCHES AND HOLDS ITS PREY. This could be a liquid-filled bath, a mucilaginous glue, or even a sudden restraining movement.

A WAY OF KILLING AND DIGESTING THE ANIMAL. In carnivorous plants this is generally achieved by smothering or crushing. Digestion is almost exclusively through enzymatic action. A number of distinct enzymes have been isolated from different genera.

THE ASSIMILATION OF VARIOUS PRODUCTS OF DIGESTION INTO THE PLANT FOR ITS BENEFIT. As carnivorous plants exhibit a wide range of trap types (which will be explained later in more detail), the range of prey they capture also varies. Bladderworts (Utricularia) possess generally tiny traps around only ¹⁄₁₀ in. (2½ mm) in diameter. They capture correspondingly small prey such as protozoans and tiny crustaceans; larger species occasionally add mosquito larvae.

A dissection of a Sarracenia pitcher in the autumn reveals the plant’s diet of flies and similar-sized insects.

Nepenthes ×mixta with a somewhat surprising prey item.

Larger-growing plants, and those of greater interest for us, catch larger insect matter. These are carnivores such as sundews, Venus flytrap, and Sarracenia pitcher plants, all of which are capable of catching large numbers of houseflies, bluebottles, and wasps. Pitcher plant leaves become gorged over the course of their season, due to their capturing efficiency.

Perhaps most intriguing of all are plants capable of enticing and holding larger creatures. If ever there were true carnivores among plants, it would be select species of the tropical pitcher plants (Nepenthes). Their traps range greatly in size, from as small as a thumbnail to the cavernous, bucket-like pitchers of Nepenthes rajah. Insects are the primary diet for the majority of species, but as the traps become bigger, so do the animals caught. Small frogs, lizards, and rodents—even rats—have been found drowned in the fluid within the pitchers’ traps. In cultivation these plants can occasionally catch mice.

I had a pitcher plant that I once hung in a tree outside in my tropical garden, during the summer months. One afternoon as I was walking by the tree, I noticed the tail feathers of a common blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) protruding from the plant’s pitcher.

This of course is far from the norm. Indeed, it was one of only a very few documented cases of birds becoming trapped by carnivorous plants in cultivation in Europe.

Exactly how the unfortunate bird came to meet its early demise is unknown. One thing is certain, however: the pitcher plant was not actively attracting birds, or there would be more than a few known cases. I believe that the bird was attracted by something else, most likely the insects being drawn to the plant. I can imagine that while perched on the front rim of the pitcher’s mouth, it leaned forward to retrieve an insect, became wedged in the trap, and drowned in the fluid.

A Venus flytrap with a small lizard. Larger prey such as this are somewhat unusual.

The large size of the prey item, in comparison to the relatively small dimensions of the trap (some 6 in. [15 cm] from the base to the bottom of the lid), meant that the leaf decayed before any nutritional gain could be made by the plant, but it does demonstrate how some of these unusual captures can occur. This type of event isn’t limited to the larger species of carnivorous plant. A number of years ago, when I operated my nursery from Surrey, a few miles south of London, I found several small lizards caught by Venus flytraps.

The diet of these plants is almost exclusively made up of insects, either crawling or flying, but they have been observed in the wild capturing small frogs—which for a large plant makes a convenient meal, as long as the animal doesn’t push itself out of the leaf with its powerful rear legs. The capture of lizards is another unusual occurrence, certainly in cultivation, and again I suspect this is the result of a blunder rather than the plant actively attracting such animals.

Assuming that these plants stick to their usual diet, they make both effective and beautiful methods of insect control around the home. On a sunny windowsill, mid-height sarracenias, some species of sundew, the cobra lily, and the Venus flytrap are effective at capturing houseflies and bluebottles, and are certainly more interesting and aesthetically pleasing than those sticky-tape traps. They’re also friendlier to us than chemical sprays.

In an environment such as a sunny conservatory or greenhouse, the range of plant sizes can be increased to include larger species and hybrids of Sarracenia—this is where an impressive display of these plants can be staged. Imagine a selection of brightly coloured, organ pipe–like pitchers in a crescendo, from the smaller species at the front up to the metre-high, fluted leaves of some forms of Sarracenia flava. A sprinkling of sundews and Venus flytraps completes the display. With the embellishment of a few props—cork bark or clean, salt-free driftwood—you have something capable of making the neighbours envious and the local insect population fearful. A similar setup can be achieved outside, especially in a sunny, sheltered position where pitcher plants make ideal candidates for containers on patios and decks, and even as interesting and unusual specimens for the margins of a pond.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING

Our knowledge of the cultural requirements of these plants has increased immeasurably over the past thirty years. Plants which in the 1980s were considered to require temperatures above freezing over the winter months are in fact quite hardy. As the availability of cultivated material increased, it enhanced our understanding of the scope of their tolerances. This broader range generally comes as a surprise to people but shows just how much more widely carnivorous plants could and should be grown.

Finally, I should make a few comments concerning the names of the plants. All plants and animals have Latin names, which follow the binomial system devised by the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). Names consist of two parts, the generic (genus) and specific (species) names. The easiest way of understanding this is to consider the two names as make and model.

Species

Let’s take the Venus flytrap, whose Latin name is Dionaea muscipula. Dionaea is the genus (make), and within that we have the species (model), which is muscipula. As there are no other species, this is called a monotypic genus.

With North American pitcher plants (Sarracenia), there are eight species, and so we have S. flava, S. leucophylla, and others. You will often see the genus name reduced to its first letter (which is always a capital), but the species name is almost always written in full, beginning with a lower case letter.

When a species is written down, it is correct to follow it with the name of the person responsible for describing it. So we have Sarracenia flava L., in which L. is the abbreviation for Carl Linnaeus himself. For the Venus flytrap, it is Dionaea muscipula Ellis. However, this rule is rarely adhered to and is considered unnecessary in anything other than scientific or taxonomic texts.

Varieties

Sometimes we have a situation in which a species is defined further, because of a certain stable characteristic which differentiates it, but not to the extent to which it can be regarded as a separate species. Sarracenia flava is a prime example, as there are seven named, naturally occurring varieties. These are written as S. flava var. flava, S. flava var. ornata, and so on. The term “var.” stands for variety, and in this instance the varieties differ little in stature but are distinct in their colours and patterning.

Subspecies

If a plant has distinct features which go further than simply, say, colour, they are categorized by subspecies, and again we can use Sarracenia to demonstrate. Sarracenia purpurea has two of these subspecies, which are written S. purpurea subsp. purpurea and S. purpurea subsp. venosa. Although the two plants are clearly the same species, they have different natural ranges and slightly different forms, one with slimmer, hairless (glabrous) leaves, and the other with much larger, more voluminous leaves, which often have a covering of fine, short hairs (pubescence).

Forms

Occasionally we see odd forms which are given legitimate status if they are naturally occurring, and we can again use Sarracenia purpurea to demonstrate. Each subspecies has an all-green variety which lacks the red pigment anthocyanin, the chemical compound which gives most plants their red colouration (anthocyanin is also used as a food colourant). Such a plant could be regarded by the layman as akin to an albino, and the easiest way to reliably identify this anomaly is to look at the emerging new growth, which is usually flushed red but in these individuals is always lime green. I mention this as there are sometimes veinless green plants found which still contain anthocyanin.

So we have Sarracenia purpurea subsp. purpurea f. heterophylla (the f. standing for forma), and S. purpurea subsp. venosa var. venosa f. pallidiflora, wherein the subspecies itself is broken down into two distinct forms.

Hybrids

A species is a plant in its purest form. A hybrid is a cross between two or more species; in the case of Sarracenia, often between other hybrids, as they are all interfertile. A primary hybrid—that is, a cross between only two species—is indicated by an × between the two names. So the cross between S. flava and S. purpurea is S. ×catesbaei, and the cross between S. flava and S. leucophylla is S. ×moorei. In the case of crosses between two hybrids, the name can be written as, for example, (S. ×catesbaei) × (S. ×moorei). Alternatively, you can list the individual components: (S. flava × S. purpurea) × (S. flava × S. leucophylla).

Cultivars

Finally, we come to cultivars. These are generally plants of horticultural origin and are names given to individual clones (genetically distinct individual plants) with outstanding characteristics. There is no limit to the number of cultivars that exist, even within an individual species or hybrid. They are given non-Latin names and are frequently named after people—for example, my own Sarracenia ‘Joyce Cooper’, in which the name of the plant is within single quotation marks, with capital lettering at the beginning of each word.

Here is a vitally important thing to remember with cultivars. Virtually all are so named because of a unique character, and so to preserve these attributes, cultivars can only be propagated vegetatively, that is by cutting, division, or tissue culture (micropropagation), in which tiny fragments of the growth points are grown in sterile jars on a nutrient jelly.

Plants should never be grown from seeds produced by a cultivar, nor labelled, swapped, or sold with that name. This applies to all plants, not just those we are covering in this book. That isn’t to say you can’t use a cultivar as a parent to produce seed; indeed there are many outstanding plants that can be raised, but the resultant offspring are to be labelled accordingly.

Very occasionally, a plant is named which has a unique characteristic that is genetic and passed on to its offspring. If it is specified in the cultivar description that any plant with this trait can be labelled as such, then it is fine to do so.

Cultivars need to be registered with a recognized body; in the case of our plants, that is the International Carnivorous Plant Society. They can also be named and described in the published catalogue of a nursery, or in a published book.