VITA SACKVILLE-WEST

(1892–1962)

VITA’S LIFEWORK AT SISSINGHURST

The genesis of an exceptional garden

For many garden lovers, Sissinghurst Castle Garden in Kent represents the height of perfection. It has become a place of pilgrimage and thousands of gardening enthusiasts visit each year to experience it at first hand. However, given the crowds that throng the garden at peak season, it is unlikely that conditions are ideal for visitors to sense the true spirit of the place, which goes deeper than a collection of outstanding plant compositions.

People often wonder what it is that sets Sissinghurst Castle Garden apart from other remarkable gardens and why, more than fifty years after the death of its creator, it still possesses such a powerful attraction. The secret of Sissinghurst’s success lies in the fact that it is inseparably linked to the lives and attitudes of Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicolson. Vita herself would be astonished, and possibly even horrified, to know that she is now no longer famous for her literary works, including The Land (1926) and other poems, and books such as The Edwardians (1930), but for her garden and what she called her ‘beastly little Observer articles’, which were later published in book form and became a bestseller. Writing was her passion, while the garden gave her a sense of balance. To some extent, Sissinghurst is like an album of memories and reflects the subjects that preoccupied Vita as an author: the countryside and love.

KNOLE CHILDHOOD

In defiance of the customs of the day, Vita Sackville-West retained her maiden name all her life, not only because of her work as a writer but, more importantly, because of her sense of pride in belonging to an aristocratic family steeped in tradition. The fact that as a woman she was not entitled to inherit Knole House, where she was born and which had been home to the Sackville family since 1603, was a source of great sadness to her all her life. It was reminders of Knole that she sought and found in Sissinghurst. During her childhood she had the run of the 300-room property, which was located near Sevenoaks, in Kent, and radiated history from every wall. The garden at Knole, extending over about 10 hectares/25 acres, was a private, magical world where this independently minded little girl would have loved to play just as she pleased, were it not for the watchful eye of the strict head gardener who guarded this particular kingdom.

A limited palette of white and green is used to great effect. The filigree framework of the central pergola is generously swathed in Rosa mulliganii.

Born in 1892 and baptized Victoria Mary Sackville-West, she was an only child and was called Vita to distinguish her from her beautiful and overbearing mother, Lady Victoria Sackville. As the daughter of a lord, Vita, like other young ladies of the era, was introduced into society. The many love affairs in which her parents indulged left her disillusioned about marriage and what she yearned for most was a companionable relationship that would make her happy. Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West, the prize-winning biography by Victoria Glendinning, provides an outstanding insight into the personal journey and complicated life of this exceptional woman, who seems to have been constantly in search of love and recognition. All this is of great significance in the story of Sissinghurst Castle and its garden, for in Harold Nicolson, a diplomat six years her senior, Vita found a man with whom she could share her life. Their marriage was far from conventional. They both had numerous friendships and relationships, but were united by the gardens at Sissinghurst, which provided them with a common bond.

The White Garden is one of Sissinghurst’s most photographed scenes. It appears in calendars and on greetings cards, and has been copied in gardens across the world.

The garden in front of South Cottage, filled with yellow kniphofias, verbascum and the daisy heads of Inula helenium, represents a sophisticated version of the cottage-garden style.

THE LONG BARN EXPERIENCE

Sissinghurst was not the family’s first garden. Their early knowledge and initial experience came from Long Barn (a few kilometres south of Knole), where they lived from 1915 to 1930. They were visited here by the famous and highly respected architect, Edwin Lutyens, a friend of Vita’s mother, who gave them much helpful advice on creating terraces. In 1917 Lutyens introduced Vita and her mother to Gertrude Jekyll. They went to see Jekyll at her home in Munstead Wood, Surrey, and Vita recorded in her notebook that she was impressed by the garden. She went on to introduce at Sissinghurst many of the same roses that grew in Jekyll’s garden. Writer Jane Brown examines this and other influences in her book entitled Vita’s Other World.

Old-fashioned ‘Henry Eckford’ sweet peas, lupins and roses around the front door add their charm to the pastoral mood.

Each of the garden enclosures at Sissinghurst has its own theme, yet all share a sense of structure and great attention to detail, as illustrated here in the Herb Garden.

END OF AN IDYLL

In 1930, Harold took the difficult decision of retiring from the diplomatic service in order to work as a journalist. That same year, their idyll at Long Barn came to an end: the property next door was sold with the intention of converting it into a chicken farm. Their search for a new home did not take long, however. In April 1930 a friend had told them of a sixteenth-century castle for sale in Kent. It sounded wonderful, but in reality was a collection of separate buildings around a central tower, surrounded by brick walls. The buildings were in a desperate state of neglect. Vita described her first impressions in the Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society published in November 1953:

‘Yet the place, when I first saw it on a summer day in 1930, caught instantly at my heart and my imagination. I fell in love: love at first sight. I saw what might be made of it. It was Sleeping Beauty’s Castle; but a castle running away into sordidness and squalor; a garden crying out for rescue.’

Vision and courage were required to take on such a project. Vita had both. In addition to the purchase price of around £12,000, Harold would need to spend a further £15,000 just to make the buildings habitable. They wondered whether it would not be more prudent to buy a new house. But Vita was charmed by the romantic atmosphere, the tower had certain architectural similarities with her beloved Knole, and Harold had also meanwhile discovered that the place had been occupied in the early sixteenth century by a member of the Sackville family. That settled matters and Sissinghurst was brought back to life.

MOVING ON

Photographs taken during the 1930s show just how much work had to be done. To the right and left of the walled-up entrance stretched a row of houses. Behind this was the tower, while on opposite boundaries stood the Priest’s House and the South Cottage. Between and abutting the buildings was an area of 4 hectares/10 acres: grass around the tower, a kitchen garden, walls, an overgrown apple orchard, and along the outer edge of the property the remains of a moat.

The tower provides an excellent view of the network of paths that cleverly links the garden’s different areas. The yew-hedge Rondel occupies a key point in the centre and forms an oasis of tranquility.

The unusual arrangement of buildings seemed to perfectly suit the family’s lifestyle. Each family member, including sons Ben and Nigel, had their own private space, in addition to shared rooms where the family could spend time together. The tower was Vita’s study and library. The boys were allotted the Priest’s House, which also incorporated the family kitchen and dining room on the ground floor. South Cottage housed Vita and Harold’s bedroom, as well as an office for Harold. Household staff were accommodated next to the main entrance, but guest rooms and a family living room were not included in the plans. In order to get from one living space to another, there was nothing for it but to brave the wind and weather and cross the open area outside. The family did not move into the property until 1932. Money was in short supply and Harold had difficulty earning a living in his new field of work. Vita, inspired by the challenges which Sissinghurst presented, was busily involved with her writing.

HAROLD’S OVERVIEW

Sissinghurst is often regarded as all Vita’s work but Harold’s role should not be forgotten. It was he, after all, who gave the garden its structure and shape. He designed a good deal of the layout from up in the tower, which gave him a good view over the property. He took care of all the measuring up and marked out the different sections with string and posts. In the ongoing battle with irregular shapes – no building was at true right angles to another – he decided to site roughly square-shaped areas in front of the Priest’s House and South Cottage. The old kitchen garden was divided into sections and criss-crossed with formal paths. Main axes, such as the Yew Walk and Moat Walk, were important routes in day-to-day life. A good deal of careful planning was necessary and the whole project took ten years to complete. The gardens in front of South Cottage and the Priest’s House were laid out in a cruciform pattern. The Lime Walk, created in 1932, connected the nuttery with the herb garden and kitchen garden. The Rondel, a circular yew hedge that forms one of the garden’s main features, was not planted until 1937. The idea for the White Garden was first conceived in 1939 but the plans were put on hold for ten years.

This organic development is what makes Sissinghurst special. Had enough money been available to carry out the project in one go, the end result might have been less successful. The sequence of walls and hedges, bisecting lines and vistas defining individual areas make the garden a compelling experience. And although these individual areas were designed to meet particular requirements, they nonetheless merge into a harmonious and satisfying whole.

VITA’S ROUTINE

Anyone wishing to retrace Vita’s daily route should start from her study in the tower, then make their way first to South Cottage and then the Priest’s House. Not surprisingly, Vita grew very familiar with the plants she passed on her way, observing them at different times of day and in every season. The plants continue to play the same important role in the garden as in Vita’s day. They lend colour, texture and scent to soften the solidity and angularity of the brickwork. A delicate, deeply romantic note characterizes the entire garden. Harold may have been responsible for the structure, but it was Vita who brought the borders to life. Travelling had awakened Vita’s feeling for botany, and visits to other gardens and houses opened up a world of opportunities. As Anne Scott-James aptly describes in Sissinghurst: The Making of a Garden, Vita had access to a higher class of garden, ‘for gardening has its own social structure, like everything else’.

In addition to grand estates such Wilton, in Wiltshire, Vita drew inspiration from several more modest sites. She shared a passion for old-fashioned roses with the owner of Kiftsgate Court (see here), Heather Muir. Roses were also one of the main features at East Lambrook Manor garden (see here). Tintinhull Garden in Somerset, established by Phyllis Reiss in the 1930s, was another of Vita’s great favourites. The two women exchanged planting ideas.

GROWING REPUTATION

Sissinghurst’s fame is largely due to Vita’s weekly columns for the Observer. The articles she wrote for this Sunday newspaper between 1946 and 1960 were practical and entertaining and appealed to the English gardening public. Later on, they were compiled in a series of four books. Vita wrote about her latest discoveries, problems in the garden, and appreciations of plants that she felt were unfairly neglected (such as aquilegias, or the rose ‘American Pillar’). Vita, who never claimed to be an expert, wrote from experience. She offered tips on where to source different plants and did not shy away from including the occasional trenchant comment. She was categorical, for example, on the subject of conifers: ‘some people like conifers: I, frankly, don’t.’

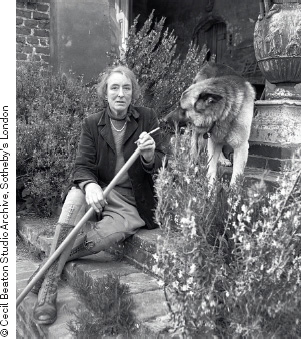

Her readers naturally wanted to see the garden for themselves. Sissinghurst had first opened to the public in 1938 and visitors were known by the family as ‘shillingses’, in reference to the entry fee. Vita was often present – a tall, striking woman, dressed in knee breeches and boots – and willing to answer questions, which contributed to the charm and character of the garden, and certainly heightened the visitors’ experience. Eccentric and outwardly self-assured, Vita had an unmistakably aristocratic bearing. She was invited as a speaker to give talks, abroad as well as in England. Prominent figures, including the Queen Mother, also visited Sissinghurst, adding to the garden’s celebrity.

Roses such as ‘Blush Rambler’ have overrun the old apple trees, enveloping them in a magical, romantic atmosphere. From this perspective, the tower appears taller and more impressive, as if it were part of a much larger estate, and is reminiscent of Knole, Vita’s beloved birthplace.

The Lime Walk along the edge of the garden is one of its main axes and was designed by Harold Nicholson. It leads towards one of the statues that adorn Sissinghurst.

The day-to-day work of mowing the lawns, cutting hedges and weeding was taken over by gardeners, while Vita concentrated on her vision for the garden. She experimented with the new and ripped out the old.

Two years before her death in 1962, Vita hired two women gardeners from Waterperry Horticultural School (see here). Pamela Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger, whom Vita simply referred to in German as ‘Mädchen’, the girls, were largely responsible for the continuity of the garden when it was handed over to the National Trust five years after Vita’s death. They maintained the garden for the new owners for another thirty-one years.

What we see today is, of necessity, a pared- down version of the original garden. Space, atmosphere and plants are the outstanding elements of Sissinghurst; it is still beautiful and yet it lacks the individual flair of its creators. Even with the Nicolson family keeping a custodial eye over the garden, it is difficult to achieve a balance between the crowds of visitors and the personality of the garden.

ROMANCE AT HEART

There is no other garden quite like Sissinghurst. The design can be copied, as can the planting, but not the location or the bygone lifestyle of Vita and Harold. As garden lovers, we have benefited from Harold’s ability to give Vita the freedom she needed to develop her talents. Whether in the famous and much-imitated White Garden, under the rose-covered apple trees of the orchard, or in the bright, hot-coloured flower beds outside South Cottage, romance is at the heart of this remarkable garden.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

|

Having Sissinghurst and Vita Sackville-West as role models should give us the confidence to landscape our own gardens gradually, over a period of years, to acquire a thorough knowledge of the place and not allow ourselves to be influenced by trends. |

|

When choosing plants, always be open to new ideas, be prepared to experiment and do not be afraid to fill up the space available. Vita was in favour of using every crack and crevice, advocating ‘Cram, cram, cram every chink and cranny.’ She was convinced that it was more effective to ‘plant twelve tulips together rather than to split them into two groups of six’. |

|

A good gardener never stops learning. Vita did not think of herself as an expert, was modest about her achievements and, above all, never shirked hard work. |

|

Anyone wanting to copy Sissinghurst will need an awkward plot of land, dilapidated buildings, a large amount of artistic talent, points of reference to which one can always return for direction, and infinite patience for immersing oneself in the world of gardens. |

SIGNATURE PLANTS

|

Climbing Rosa mulliganii. |

|

Lilies such as Lilium regale or ‘Apollo’. |

|

White tansy (Achillea ptarmica). |

|

Delphinium ‘Ice Cap’. |

|

White rosebay willowherb (Chamaenerion angustifolium ‘Album’). |

|

Scotch thistle (Onopordum). |

|

Wisteria brachybotrys ‘Shiro-kapitan’. |