ROSEMARY VEREY

(1918–2001)

Things could have turned out very differently. Barnsley House, situated in Gloucestershire, one of England’s most beautiful counties, might have been purchased by a private owner who could well have closed its gates forever. This exceptional garden would then have lived on only in people’s memories, in books and in photographs. However, Barnsley House has been lucky; as have we, the garden-visiting public, who can continue to draw inspiration at first hand from Rosemary Verey’s masterpiece.

When Rosemary Verey, the creator of this exceptional garden, died in 2001 and her son Charles took the decision to sell Barnsley House, there were considerable fears for the garden’s future. Since 1970, when the garden first opened to the public as part of the National Gardens Scheme, it had welcomed a constant stream of visitors. Up until the year 2000 around 25,000 people a year made their way to Barnsley, a small village in the southern part of the Cotswolds near Cirencester. It was on the list of must-see destinations for anyone passionate about gardening or the English countryside. Barnsley was a dream garden and Rosemary Verey an inspiration. Everyone wanted to take a little piece of Barnsley home with them, be it a plant or ideas to try out for themselves. It came to be viewed as the epitome of an English country house garden: elaborate, even lavish, infused with an air of romance, featuring long vistas, exuberant flower displays and leafy corners offering peaceful seclusion.

Two hoteliers from the village bought the property and converted Barnsley House into a boutique hotel that perfectly combined the old and the new. The garden was its focal point; guests could breakfast on the terrace, take a drink beside the temple or simply enjoy a stroll. The vegetable garden supplied produce for the kitchen and was even extended to cater for the demand. But the investment and running costs were enormous, too high for a small enterprise, and in 2009 the property was sold to Calcot Health and Leisure. Since then, head gardener Richard Gatenby, who was hired during Rosemary Verey’s lifetime, has been able to look towards the future and develop a maintenance plan – an important step, since this is not the sort of garden that can be left to its own devices. Traditional working methods, organizational skills and extensive plant knowledge are essential.

Barnsley House garden is not to everyone’s taste; many find the style a little too fussy and flowery. But it suits Richard, which is just as well considering all the time he devotes to it. He likes the complex, multi-layered style of planting, the preference for interesting and special plants, and the predominantly pastel colour combinations – all characteristics favoured by Rosemary Verey. When he applied for a position at Barnsley fourteen years ago, he was interviewed first by Charles Verey (who took over the house in 1988) before being introduced to Rosemary Verey. After they had discussed all the usual job-related business, their conversation turned to whippets. They discovered that they shared a passion not only for this nimble breed of dog but also for Laurie Lee’s novel Cider with Rosie, and so Richard was given the job.

ENGLISH EPITOME

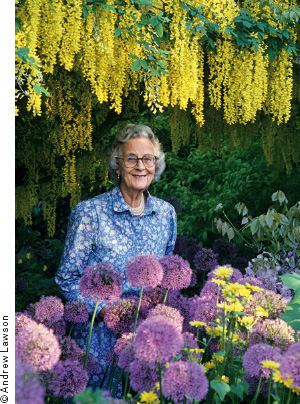

Despite changing trends in the garden world, magazine editors still love this photogenic garden. Pictures of the Laburnum Walk, or of the Knot Garden or potager, regularly appear in garden and design publications. Barnsley was the ultimate garden of the 1980s and 1990s and its creator, Rosemary Verey, perfectly fitted the image of an English lady. She had, for me, something of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple about her, an air of belonging to the old school. Born in 1919, she grew up at a time when young women from good families were expected to get married and look after a household. Despite this prevailing expectation, she attended University College London, which was then as it is today a world-class university. There she studied economics and social history, but married in 1939 before graduating. Fame and a career as both a writer of gardening books and garden designer did not come until the 1980s, when Rosemary Verey was already over sixty. And it all began with her garden.

All-seeing, all-knowing, always correctly dressed, courteous, full of energy and extremely self-assertive, Rosemary Verey belonged, like the Queen, to the generation that continued working until an advanced age. People treated her with great deference and even today refer to her respectfully as ‘Mrs Verey’. She lived at Barnsley House for nearly fifty years, first in the house itself and later, after the death of her husband in 1984, in a smaller adjoining cottage. It is often not appreciated that her love of gardening developed over time. When her husband, architectural historian David Verey, inherited the seventeenth-century house with its 2 hectares/5 acres of garden in 1958, Rosemary Verey was more interested in horses than plants. A riding accident, coupled with the influence of her husband, was to change this. In 1962 David Verey had a neoclassical temple transported stone by stone from Fairford Park, about 12 kilometres/8 miles away, and erected in the far corner of the Walled Garden. He had a special interest in preserving the country’s historical legacy through his work as senior investigator of historic buildings for the Ministry of Housing, particularly since this was an era when large country houses like Fairford were being demolished or were falling into neglect as a consequence of high taxation and crippling death duties. Once the temple was in place, it was decided to construct a pool and complete the area with iron railings, thus laying the foundation of the outstanding garden that was to follow.

The Knot Garden, based on a seventeenth-century design, leads into a park-like sweep of lawn. Clipped topiary shapes contrast with the freely growing trees beyond.

These spring beds illustrate the careful planning, the often playful touches and the delicate colour combinations that make this garden so special.

Mrs Verey believed that a garden should make an impression all year round, offering a succession of overlapping highlights. Under the tunnel of laburnum and wisteria, not yet in bloom, brilliant red ‘Apeldoorn’ tulips provide a striking show of colour. Alliums in bud promise to carry the display through to summer.

Along the vista from the temple, parallel to the high wall, David Verey planted a lime walk using Tilia platyphyllos ‘Rubra’, which was to be kept clipped in the style of French topiary. It was, however, his wife’s idea to continue the walk, extending it with a tunnel of laburnum and wisteria. Five Laburnum × watereri ‘Vossii’ and five purple-flowered wisterias were planted either side of the path and supported by bespoke but simple metal arches. This was the beginning of the famous ‘Barnsley’ successional flowering: as one plant finishes flowering it is followed by the next in an apparently seamless transition. This approach was carried through to the ground cover beneath the arches of the Laburnum Walk, where red tulips are succeeded by a mass of purple alliums.

Barnsley House illustrates how gradual development inspired by both beauty and function can benefit a garden. The long herb garden, a tribute to the Elizabethan age, was created in 1976 when Rosemary Verey wearied of always having to walk to the bottom of the garden for her culinary herbs and decided to plant them in a formal bed near the kitchen door. Her husband suggested consulting historic books such as The Country Farm (1616), Gervase Markham’s revised translation of a French treatise called La Maison Rustique. This inspired her to create a long, narrow bed with low box hedging laid out in a diamond pattern, thus providing separate compartments for each herb. By cleverly combining the useful with the aesthetic, dill, chives, coriander and thyme were elevated to things of beauty. And with this mini knot garden barely 2m/6ft wide, Rosemary Verey succeeded in reviving a design feature from the past.

A smooth, open lawn provides an important natural break between intimate, delicately planted beds, such as this spring border along the edge of the terrace, and the strict formality of the yew domes and the clipped lime tree avenue in the background.

Being inspired by others is nothing new, as is evident throughout the history of garden design. Regardless of where the ideas come from, however, it is important above all to choose the right design for one’s own garden. Slavishly copying other people was not Rosemary Verey’s style. Head gardener Richard Gatenby relates how she wrote him this dedication inside one of her books: ‘Hope you enjoy having your input.’ It is this sentiment that prevails at Barnsley House, seeking inspiration then adapting it to fit one’s own vision. As well as drawing on influential books of previous centuries, the Vereys visited nearby gardens, including Hidcote Manor. They both came away impressed but decided that ‘while each part of our garden must have its own theme and character, the garden as a whole would not benefit from being divided into such clearly defined “rooms”.’ The Vereys had made a wise choice, as the garden at Barnsley House is considerably smaller than Hidcote. In addition, the layout of their plot is different, featuring a park-like front garden sloping down to the road and a roughly square main garden at the back. It was for this reason that the Vereys decided against severely trimmed hedges, preferring to use decorative shrubs and herbaceous borders to screen and define separate areas.

The neoclassical temple, rescued from a nearby stately home, was to some extent the linchpin of the new garden. The metal gates open on to a long vista stretching towards the Laburnum Walk.

The flower beds at Barnsley House are deep, in some cases more than 5m/16ft, allowing plenty of room for trees and shrubs as well as perennials and bulbs. It is only by analyzing the beds in detail that the complexity of the plant schemes become apparent. The beds are built up in layers towards the centre where they form a high point, almost like a curtain, filtering the views beyond and thereby creating a sense of depth. All plants are of similar weighting, all equally important, and they merge to form an exquisite yet complex composition reminiscent of a fine Gobelin tapestry. This type of planting became Rosemary Verey’s signature style, and although labour-intensive and costly was exported the world over.

In her book Rosemary Verey’s Garden Plans, she describes her first steps in the design process and how she found it was something she enjoyed doing. She realized that ‘the position of the house, the path lined with yew trees and the 1770 stone wall around the garden made it impossible to be too precise. On the ground, so long as you keep a certain symmetry, you do not notice the discrepancies that seem obvious on paper.’ The garden is distinguished by a structure that is neither rigid or forced but acknowledges the quirks of its setting. It is also the loose symmetry that balances the garden. Quick to learn, widely read and prepared to listen to suggestions, Rosemary Verey adopted an important piece of advice from the garden designer and plantsman Russell Page: ‘Every garden needs an open space for you to walk into, a place where you can take a deep breath, contemplate your surroundings and enjoy the moment.’ At Barnsley House, the large lawn behind the house fills this role. It creates a sense of space, being a neutral, calm area separate from the three-dimensionality of the planting. Standing with your back to the house, you can sense that the garden extends outwards at either side. Parallel to the Laburnum Walk and contrasting with its formal feel is a set of beds planted in a more country garden style. Gold and green are the predominant colours here, provided by Bowles’s golden grass (Milium effusum ‘Aureum’), hostas, lamium and many others, the names of which would fill several pages.

Paving, plants and colour: three elements of the iconic Laburnum Walk. It has been copied many times but nowhere else is the effect as perfect as at Barnsley House.

When appropriate, Rosemary Verey kept things simple and functional. Before making the herb garden, she planted a knot garden beside the house so it could be viewed to best advantage from the window of an upstairs room. For the design of the two squares measuring 3 by 3m/10 by 10ft, she borrowed from Gervase Markham’s The Country Farm and another book, The Complete Gardener’s Practice (1664) by Stephen Blake. She created the outline of the interlacing knot pattern by using common box hedging (Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’), gold-edged B. sempervirens ‘Aureovariegata’, shrubby germander (Teucrium × lucidrys) as well as topiary box balls and Santolina chamaecyparissus. The compartments were filled with gravel to emphasize the rhythm of the hedging weaving in and out. Rosemary Verey could be credited with reintroducing knot gardens, which were fashionable during the Renaissance, to the wider gardening public. By the end of the 1980s every garden worth its salt had a knot garden; in London there were even some tiny gardens that consisted of a single love-knot. Word of Barnsley’s magic began to spread and Rosemary Verey became sought-after as a garden designer. Although she only designed two gardens in their entirety – those at Barnsley House and a show garden at the Chelsea Flower Show of 1992 – her influence is nevertheless evident in many famous gardens.

People often forget nowadays that Rosemary Verey played a pivotal role in making vegetable gardens chic. Long before it became fashionable to grow vegetables in the garden, Rosemary Verey had designed her own potager, inspired by another Gervase Markham book, The English Housewife (1631). However, she did have to wait until 1979 before she could put her ideas into practice, as the incumbent gardener, Arthur Turner, was very set in his ways. The potager was separate from the main garden, lying on the other side of a lane outside the garden wall. Enclosed within its own dry-stone wall, it resembled a miniature version of the famous potager at the Château de Villandry in central France, but in Verey style. Serious vegetable growers might have shaken their heads at the sight of box-edged beds and colourful arrangements of green and red oak leaf lettuce, but Mrs Verey thought they were splendid and her kitchen garden provided enough fruit and vegetables for the family table. She started a vegetable trend that spread widely, into Europe and other parts of the world. When Richard Gatenby first came to Barnsley House he worked initially in the potager. Yorkshire born and bred, with a father who grew award-winning vegetables, he remembers how he pulled out all the stops to produce some magnificent specimens. Charles Verey, however, declared them to be vulgar. It was, after all, not about competing in the annual village show but all about appearance and elegance. Nowadays this area is tended with great sensitivity by Ed Alderman.

ROYAL INFLUENCE

During Rosemary Verey’s lifetime, visitors entered the garden by a route that took them past the glasshouses rather than through the front garden, which did not really feature in the garden visit. The emphasis was on the main garden, on vistas and axes like the yew-bordered path leading up to the house, dotted with thyme and other plants contentedly growing in the gaps between paving stones. Delicate little pink and blue flowers sprang up everywhere so you had to be careful where you trod, but the scent that wafted up from them was deliciously suggestive of the Mediterranean. Prince Charles was so taken with this planting feature that he introduced it, in a slightly different form, as a Thyme Walk in his garden at Highgrove.

As a mark of the high acclaim Rosemary Verey enjoyed in the gardening world, she was invited in 1992 to create a garden for the Chelsea Flower Show. This was followed by further honours: in 1996 she was awarded an OBE by Queen Elizabeth II, and in 2000 featured in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Five Centuries of Women and Gardens. Rosemary Verey also broke into the North American market, where her style became hugely popular, fulfilling, as it did, all the criteria required of an English garden. It was in the USA that she gave her last public lectures. The links with north America are still intact. All Mrs Verey’s garden plans are held in the archives of the New York Botanical Garden, and in 2012 a biography by American lawyer Barbara Paul Robinson was published, entitled Rosemary Verey: The Life and Lessons of a Legendary Gardener. Robinson had the privilege of spending a few months working with Rosemary Verey, thus gaining valuable insights into her career and creative world.

Inspired by the potagers of France, Rosemary Verey developed a distinctly English style of kitchen garden. Aquilegia, forget-me-nots (Myosotis), Welsh poppies (Meconopsis cambrica) and topiary form a decorative edging around the vegetable beds.

If one plant combination reflects Mrs Verey’s distinctive style more than any other, it is surely tulips (as in ‘Blue Diamond’, pictured here) underplanted with forget-me-nots (Myosotis) and set against a backdrop of neon-green Smyrnium perfoliatum.

The garden at Barnsley House has inevitably changed in some ways, but has lost none of its distinctive flair. A new generation is learning to appreciate the ambience of the place. These are the city-dwellers who spend their weekends in the country. They are able to enjoy the interiors of this elegant country house hotel, savour delicious food conjured up by the chefs from kitchen garden produce, and wander at leisure in the gardens. Whether they realize it or not, they are caught up in the garden’s magic – and one day they may find themselves planting forget-me-nots and pink tulips.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

|

Gather and adapt ideas. |

|

Combine a formal framework with lavish planting. |

|

Introduce main axes and vistas, and furnish them with displays of flowering plants. |

|

Build up layers of trees and shrubs, herbaceous plants, ornamental grasses, bulbs and corms. |

|

Integrate historic features in appropriate spots. |

|

Know, appreciate and take care of your plants. |

|

Do not stint on time or money. This type of garden is the very opposite of thrifty and low-maintenance. |

SIGNATURE PLANTS

|

Old-English plants, such as forget-me-not (Myosotis). |

|

Honesty (Lunaria annua). |

|

Tulips in a range of varieties, such as ‘China Pink’. |

|

Geranium ‘Johnson’s Blue’ and other cranesbills. |

|

Lamium maculatum (spotted deadnettle) or its cultivar ‘Pink Pewter’. |

|

Bronze fennel (Foeniculum vulgare ‘Purpureum’). |

|

Laburnum × watereri ‘Vossii’, seen here with Allium aflatunense. |