WE HAVE SEEN how people describe the common characteristics of optimal experience: a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-hound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous.

But how do such experiences happen? Occasionally flow may occur by chance, because of a fortunate coincidence of external and internal conditions. For instance, friends may be having dinner together, and someone brings up a topic that involves everyone in the conversation. One by one they begin to make jokes and tell stories, and pretty soon all are having fun and feeling good about one another. While such events may happen spontaneously, it is much more likely that flow will result either from a structured activity, or from an individual’s ability to make flow occur, or both.

Why is playing a game enjoyable, while the things we have to do every day—like working or sitting at home—are often so boring? And why is it that one person will experience joy even in a concentration camp, while another gets the blahs while vacationing at a fancy resort? Answering these questions will make it easier to understand how experience can be shaped to improve the quality of life. This chapter will explore those particular activities that are likely to produce optimal experiences, and the personal traits that help people achieve flow easily.

When describing optimal experience in this book, we have given as examples such activities as making music, rock climbing, dancing, sailing, chess, and so forth. What makes these activities conducive to flow is that they were designed to make optimal experience easier to achieve. They have rules that require the learning of skills, they set up goals, they provide feedback, they make control possible. They facilitate concentration and involvement by making the activity as distinct as possible from the so-called “paramount reality” of everyday existence. For example, in each sport participants dress up in eye-catching uniforms and enter special enclaves that set them apart temporarily from ordinary mortals. For the duration of the event, players and spectators cease to act in terms of common sense, and concentrate instead on the peculiar reality of the game.

Such flow activities have as their primary function the provision of enjoyable experiences. Play, art, pageantry; ritual, and sports are some examples. Because of the way they are constructed, they help participants and spectators achieve an ordered state of mind that is highly enjoyable.

Roger Caillois, the French psychological anthropologist, has divided the world’s games (using that word in its broadest sense to include every form of pleasurable activity) into four broad classes, depending on the kind of experiences they provide. Agon includes games that have competition as their main feature, such as most sports and athletic events; alea is the class that includes all games of chance, from dice to bingo; ilinx, or vertigo, is the name he gives to activities that alter consciousness by scrambling ordinary perception, such as riding a merry-go-round or skydiving; and mimicry is the group of activities in which alternative realities are created, such as dance, theater, and the arts in general.

Using this scheme, it can be said that games offer opportunities to go beyond the boundaries of ordinary experience in four different ways. In agonistic games, the participant must stretch her skills to meet the challenge provided by the skills of the opponents. The roots of the word “compete” are the Latin con petire, which meant “to seek together.” What each person seeks is to actualize her potential, and this task is made easier when others force us to do our best. Of course, competition improves experience only as long as attention is focused primarily on the activity itself. If extrinsic goals—such as beating the opponent, wanting to impress an audience, or obtaining a big professional contract—are what one is concerned about, then competition is likely to become a distraction, rather than an incentive to focus consciousness on what is happening.

Aleatory games are enjoyable because they give the illusion of controlling the inscrutable future. The Plains Indians shuffled the marked rib bones of buffaloes to predict the outcome of the next hunt, the Chinese interpreted the pattern in which sticks fell, and the Ashanti of East Africa read the future in the way their sacrificed chickens died. Divination is a universal feature of culture, an attempt to break out of the constraints of the present and get a glimpse of what is going to happen. Games of chance draw on the same need. The buffalo ribs become dice, the sticks of the I Ching become playing cards, and the ritual of divination becomes gambling—a secular activity in which people try to outsmart each other or try to outguess fate.

Vertigo is the most direct way to alter consciousness. Small children love to turn around in circles until they are dizzy; the whirling dervishes in the Middle East go into states of ecstasy through the same means. Any activity that transforms the way we perceive reality is enjoyable, a fact that accounts for the attraction of “consciousness-expanding” drugs of all sorts, from magic mushrooms to alcohol to the current Pandora’s box of hallucinogenic chemicals. But consciousness cannot be expanded; all we can do is shuffle its content, which gives us the impression of having broadened it somehow. The price of most artificially induced alterations, however, is that we lose control over that very consciousness we were supposed to expand.

Mimicry makes us feel as though we are more than what we actually are through fantasy, pretense, and disguise. Our ancestors, as they danced wearing the masks of their gods, felt a sense of powerful identification with the forces that ruled the universe. By dressing like a deer, the Yaqui Indian dancer felt at one with the spirit of the animal he impersonated. The singer who blends her voice in the harmony of a choir finds chills running down her spine as she feels at one with the beautiful sound she helps create. The little girl playing with her doll and her brother pretending to be a cowboy also stretch the limits of their ordinary experience, so that they become, temporarily, someone different and more powerful—as well as learn the gender-typed adult roles of their society.

In our studies, we found that every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, had this in common: It provided a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality. It pushed the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. In short, it transformed the self by making it more complex. In this growth of the self lies the key to flow activities.

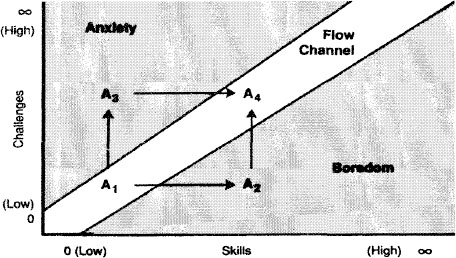

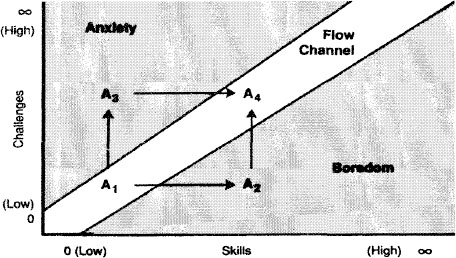

A simple diagram might help explain why this should be the case. Let us assume that the figure below represents a specific activity—for example, the game of tennis. The two theoretically most important dimensions of the experience, challenges and skills, are represented on the two axes of the diagram. The letter A represents Alex, a boy who is learning to play tennis. The diagram shows Alex at four different points in time. When he first starts playing (A1), Alex has practically no skills, and the only challenge he faces is hitting the ball over the net. This is not a very difficult feat, but Alex is likely to enjoy it because the difficulty is just right for his rudimentary skills. So at this point he will probably be in flow. But he cannot stay there long. After a while, if he keeps practicing, his skills are bound to improve, and then he will grow bored just batting the ball over the net (A2). Or it might happen that he meets a more practiced opponent, in which case he will realize that there are much harder challenges for him than just lobbing the ball—at that point, he will feel some anxiety (A3) concerning his poor performance.

Neither boredom nor anxiety are positive experiences, so Alex will be motivated to return to the flow state. How is he to do it? Glancing again at the diagram, we see that if he is bored (A2) and wishes to be in flow again, Alex has essentially only one choice: to increase the challenges he is facing. (He also has a second choice, which is to give up tennis altogether—in which case A would simply disappear from the diagram.) By setting himself a new and more difficult goal that matches his skills—for instance, to beat an opponent just a little more advanced than he is—Alex would be back in flow (A4).

If Alex is anxious (A3), the way back to flow requires that he increase his skills. Theoretically he could also reduce the challenges he is facing, and thus return to flow where he started (in A1), but in practice it is difficult to ignore challenges once one is aware that they exist.

The diagram shows that both A1 and A4 represent situations in which Alex is in flow. Although both are equally enjoyable, the two states are quite different in that A4 is a more complex experience than A1. It is more complex because it involves greater challenges, and demands greater skills from the player.

But A4, although complex and enjoyable, does not represent a stable situation, either. As Alex keeps playing, either he will become bored by the stale opportunities he finds at that level, or he will become anxious and frustrated by his relatively low ability. So the motivation to enjoy himself again will push him to get back into the flow channel, but now at a level of complexity even higher than A4.

It is this dynamic feature that explains why flow activities lead to growth and discovery. One cannot enjoy doing the same thing at the same level for long. We grow either bored or frustrated; and then the desire to enjoy ourselves again pushes us to stretch our skills, or to discover new opportunities for using them.

It is important, however, not to fall into the mechanistic fallacy and expect that, just because a person is objectively involved in a flow activity, she will necessarily have the appropriate experience. It is not only the “real” challenges presented by the situation that count, but those that the person is aware of. It is not skills we actually have that determine how we feel, but the ones we think we have. One person may respond to the challenge of a mountain peak but remain indifferent to the opportunity to learn to play a piece of music; the next person may jump at the chance to learn the music and ignore the mountain. How we feel at any given moment of a flow activity is strongly influenced by the objective conditions; but consciousness is still free to follow its own assessment of the case. The rules of games are intended to direct psychic energy in patterns that are enjoyable, but whether they do so or not is ultimately up to us. A professional athlete might be “playing” football without any of the elements of flow being present: he might be bored, self-conscious, concerned about the size of his contract rather than the game. And the opposite is even more likely—that a person will deeply enjoy activities that were intended for other purposes. To many people activities like working or raising children provide more flow than playing a game or painting a picture, because these individuals have learned to perceive opportunities in such mundane tasks that others do not see.

During the course of human evolution, every culture has developed activities designed primarily to improve the quality of experience. Even the least technologically advanced societies have some form of art, music, dance, and a variety of games that children and adults play. There are natives of New Guinea who spend more time looking in the jungle for the colorful feathers they use for decoration in their ritual dances than they spend looking for food. And this is by no means a rare example: art, play, and ritual probably occupy more time and energy in most cultures than work.

While these activities may serve other purposes as well, the fact that they provide enjoyment is the main reason they have survived. Humans began decorating caves at least thirty thousand years ago. These paintings surely had religious and practical significance. However, it is likely that the major raison d’être of art was the same in the Paleolithic era as it is now—namely, it was a source of flow for the painter and for the viewer.

In fact, flow and religion have been intimately connected from earliest times. Many of the optimal experiences of mankind have taken place in the context of religious rituals. Not only art but drama, music, and dance had their origins in what we now would call “religious” settings; that is, activities aimed at connecting people with supernatural powers and entities. The same is true of games. One of the earliest ball games, a form of basketball played by the Maya, was part of their religious celebrations, and so were the original Olympic games. This connection is not surprising, because what we call religion is actually the oldest and most ambitious attempt to create order in consciousness. It therefore makes sense that religious rituals would be a profound source of enjoyment.

In modern times art, play, and life in general have lost their supernatural moorings. The cosmic order that in the past helped interpret and give meaning to human history has broken down into disconnected fragments. Many ideologies are now competing to provide the best explanation for the way we behave: the law of supply and demand and the “invisible hand” regulating the free market seek to account for our rational economic choices; the law of class conflict that underlies historical materialism tries to explain our irrational political actions; the genetic competition on which sociobiology is based would explain why we help some people and exterminate others; behaviorism’s law of effect offers to explain how we learn to repeat pleasurable acts, even when we are not aware of them. These are some of the modern “religions” rooted in the social sciences. None of them—with the partial exception of historical materialism, itself a dwindling creed—commands great popular support, and none has inspired the aesthetic visions or enjoyable rituals that previous models of cosmic order had spawned.

As contemporary flow activities are secularized, they are unlikely to link the actor with powerful meaning systems such as those the Olympic games or the Mayan ball games provided. Generally their content is purely hedonic: we expect them to improve how we feel, physically or mentally, but we do not expect them to connect us with the gods. Nevertheless, the steps we take to improve the quality of experience are very important for the culture as a whole. It has long been recognized that the productive activities of a society are a useful way of describing its character: thus we speak of hunting-gathering, pastoral, agricultural, and technological societies. But because flow activities are freely chosen and more intimately related to the sources of what is ultimately meaningful, they are perhaps more precise indicators of who we are.

A major element of the American experiment in democracy has been to make the pursuit of happiness a conscious political goal—indeed, a responsibility of the government. Although the Declaration of Independence may have been the first official political document to spell out this goal explicitly, it is probably true that no social system has ever survived long unless its people had some hope that their government would help them achieve happiness. Of course there have been many repressive cultures whose populace was willing to tolerate even extremely wretched rulers. If the slaves who built the Pyramids rarely revolted it was because compared to the alternatives they perceived, working as slaves for the despotic Pharaohs offered a marginally more hopeful future.

Over the past few generations social scientists have grown extremely unwilling to make value judgments about cultures. Any comparison that is not strictly factual runs the risk of being interpreted as invidious. It is bad form to say that one culture’s practice, or belief, or institution is in any sense better than another’s. This is “cultural relativism,” a stance anthropologists adopted in the early part of this century as a reaction against the overly smug and ethnocentric assumptions of the colonial Victorian era, when the Western industrial nations considered themselves to be the pinnacle of evolution, better in every respect than technologically less developed cultures. This naive confidence of our supremacy is long past. We might still object if a young Arab drives a truck of explosives into an embassy, blowing himself up in the process; but we can no longer feel morally superior in condemning his belief that Paradise has special sections reserved for self-immolating warriors. We have come to accept that our morality simply no longer has currency outside our own culture. According to this new dogma, it is inadmissible to apply one set of values to evaluate another. And since every evaluation across cultures must necessarily involve at least one set of values foreign to one of the cultures being evaluated, the very possibility of comparison is ruled out.

If we assume, however, that the desire to achieve optimal experience is the foremost goal of every human being, the difficulties of interpretation raised by cultural relativism become less severe. Each social system can then be evaluated in terms of how much psychic entropy it causes, measuring that disorder not with reference to the ideal order of one or another belief system, but with reference to the goals of the members of that society. A starting point would be to say that one society is “better” than another if a greater number of its people have access to experiences that are in line with their goals. A second essential criterion would specify that these experiences should lead to the growth of the self on an individual level, by allowing as many people as possible to develop increasingly complex skills.

It seems clear that cultures differ from one another in terms of the degree of the “pursuit of happiness” they make possible. The quality of life in some societies, in some historical periods, is distinctly better than in others. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, the average Englishman was probably much worse off than he had been earlier, or would be again a hundred years later. The evidence suggests that the Industrial Revolution not only shortened the life spans of members of several generations, but made them more nasty and brutish as well. It is hard to imagine that weavers swallowed by the “Satanic mills” at five years of age, who worked seventy hours a week or more until they dropped dead from exhaustion, could feel that what they were getting out of life was what they wanted, regardless of the values and beliefs they shared.

To take another example, the culture of the Dobu islanders, as described by the anthropologist Reo Fortune, is one that encouraged constant fear of sorcery, mistrust among even the closest relatives, and vindictive behavior. Just going to the bathroom was a major problem, because it involved stepping out into the bush, where everybody expected to be attacked by bad magic when alone among the trees. The Dobuans didn’t seem to “like” these characteristics so pervasive in their everyday experience, but they were unaware of alternatives. They were caught in a web of beliefs and practices that had evolved through time, and that made it very difficult for them to experience psychic harmony. Many ethnographic accounts suggest that built-in psychic entropy is more common in preliterate cultures than the myth of the “noble savage” would suggest. The Ik of Uganda, unable to cope with a deteriorating environment that no longer provides enough food for them to survive, have institutionalized selfishness beyond the wildest dreams of capitalism. The Yonomamo of Venezuela, like many other warrior tribes, worship violence more than our militaristic superpowers, and find nothing as enjoyable as a good bloody raid on a neighboring village. Laughing and smiling were almost unknown in the Nigerian tribe beset by sorcery and intrigue that Laura Bohannaw studied.

There is no evidence that any of these cultures chose to be selfish, violent, or fearful. Their behavior does not make them happier; on the contrary, it causes suffering. Such practices and beliefs, which interfere with happiness, are neither inevitable nor necessary; they evolved by chance, as a result of random responses to accidental conditions. But once they become part of the norms and habits of a culture, people assume that this is how things must be; they come to believe they have no other options.

Fortunately there are also many instances of cultures that, either by luck or by foresight, have succeeded in creating a context in which flow is relatively easy to achieve. For instance, the pygmies of the Ituri forest described by Colin Turnbull live in harmony with one another and their environment, filling their lives with useful and challenging activities. When they are not hunting or improving their villages they sing, dance, play musical instruments, or tell stories to each other. As in many so-called “primitive” cultures, every adult in this pygmy society is expected to be a bit of an actor, singer, artist, and historian as well as a skilled worker. Their culture would not be given a high rating in terms of material achievement, but in terms of providing optimal experiences their way of life seems to be extremely successful.

Another good example of how a culture can build flow into its life-style is given by the Canadian ethnographer Richard Kool, describing one of the Indian tribes of British Columbia:

The Shushwap region was and is considered by the Indian people to be a rich place: rich in salmon and game, rich in below-ground food resources such as tubers and roots—a plentiful land. In this region, the people would live in permanent village sites and exploit the environs for needed resources. They had elaborate technologies for very effectively using the resources of the environment, and perceived their lives as being good and rich. Yet, the elders said, at times the world became too predictable and the challenge began to go out of life. Without challenge, life had no meaning.

So the elders, in their wisdom, would decide that the entire village should move, those moves occurring every 25 to 30 years. The entire population would move to a different part of the Shushwap land and there, they found challenge. There were new streams to figure out, new game trails to learn, new areas where the balsamroot would be plentiful. Now life would regain its meaning and be worth living. Everyone would feel rejuvenated and healthy. Incidentally, it also allowed exploited resources in one area to recover after years of harvesting. . . .

An interesting parallel is the Great Shrine at Isé, south of Kyoto, in Japan. The Isé Shrine was built about fifteen hundred years ago on one of a pair of adjacent fields. Every twenty years or so it has been taken down from the field it has been standing on, and rebuilt on the next one. By 1973 it had been reerected for the sixtieth time. (During the fourteenth century conflict between competing emperors temporarily interrupted the practice.)

The strategy adopted by the Shushwap and the monks of Isé resembles one that several statesmen have only dreamed about accomplishing. For example, both Thomas Jefferson and Chairman Mao Zedong believed that each generation needed to make its own revolution for its members to stay actively involved in the political system ruling their lives. In reality, few cultures have ever attained so good a fit between the psychological needs of their people and the options available for their lives. Most fall short, either by making survival too strenuous a task, or by closing themselves off into rigid patterns that stifle the opportunities for action by each succeeding generation.

Cultures are defensive constructions against chaos, designed to reduce the impact of randomness on experience. They are adaptive responses, just as feathers are for birds and fur is for mammals. Cultures prescribe norms, evolve goals, build beliefs that help us tackle the challenges of existence. In so doing they must rule out many alternative goals and beliefs, and thereby limit possibilities; but this channeling of attention to a limited set of goals and means is what allows effortless action within self-created boundaries.

It is in this respect that games provide a compelling analogy to cultures. Both consist of more or less arbitrary goals and rules that allow people to become involved in a process and act with a minimum of doubts and distractions. The difference is mainly one of scale. Cultures are all-embracing: they specify how a person should be born, how she should grow up, marry, have children, and die. Games fill out the interludes of the cultural script. They enhance action and concentration during “free time,” when cultural instructions offer little guidance, and a person’s attention threatens to wander into the uncharted realms of chaos.

When a culture succeeds in evolving a set of goals and rules so compelling and so well matched to the skills of the population that its members are able to experience flow with unusual frequency and intensity, the analogy between games and cultures is even closer. In such a case we can say that the culture as a whole becomes a “great game.” Some of the classical civilizations may have succeeded in reaching this state. Athenian citizens, Romans who shaped their actions by virtus, Chinese intellectuals, or Indian Brahmins moved through life with intricate grace, and derived perhaps the same enjoyment from the challenging harmony of their actions as they would have from an extended dance. The Athenian polis, Roman law, the divinely grounded bureaucracy of China, and the all-encompassing spiritual order of India were successful and lasting examples of how culture can enhance flow—at least for those who were lucky enough to be among the principal players.

A culture that enhances flow is not necessarily “good” in any moral sense. The rules of Sparta seem needlessly cruel from the vantage point of the twentieth century, even though they were by all accounts successful in motivating those who abided by them. The joy of battle and the butchery that exhilarated the Tartar hordes or the Turkish Janissaries were legendary. It is certainly true that for great segments of the European population, confused by the dislocating economic and cultural shocks of the 1920s, the Nazi-fascist regime and ideology provided an attractive game plan. It set simple goals, clarified feedback, and allowed a renewed involvement with life that many found to be a relief from prior anxieties and frustrations.

Similarly, while flow is a powerful motivator, it does not guarantee virtue in those who experience it. Other things being equal, a culture that provides flow might be seen as “better” than one that does not. But when a group of people embraces goals and norms that will enhance its enjoyment of life there is always the possibility that this will happen at the expense of someone else. The flow of the Athenian citizen was made possible by the slaves who worked his property, just as the elegant life-style of the Southern plantations in America rested on the labor of imported slaves.

We are still very far from being able to measure with any accuracy how much optimal experience different cultures make possible. According to a large-scale Gallup survey taken in 1976, 40 percent of North Americans said that they were “very happy,” as opposed to 20 percent of Europeans, 18 percent of Africans, and only 7 percent of Far Eastern respondents. On the other hand, another survey conducted only two years earlier indicated that the personal happiness rating of U.S. citizens was about the same as that of Cubans and Egyptians, whose per-capita GNPs were respectively five and over ten times less than that of the Americans. West Germans and Nigerians came out with identical happiness ratings, despite an over fifteenfold difference in per-capita GNP. So far, these discrepancies only demonstrate that our instruments for measuring optimal experience are still very primitive. Yet the fact that differences do exist seems incontestable.

Despite ambiguous findings, all large-scale surveys agree that citizens of nations that are more affluent, better educated, and ruled by more stable governments report higher levels of happiness and satisfaction with life. Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands appear to be the happiest countries, and the United States, despite high rates of divorce, alcoholism, crime, and addictions, is not very far behind. This should not be surprising, given the amount of time and resources we spend on activities whose main purpose is to provide enjoyment. Average American adults work only about thirty hours a week (and spend an additional ten hours doing things irrelevant to their jobs while at the workplace, such as daydreaming or chatting with fellow workers). They spend a slightly smaller amount of time—on the order of twenty hours per week—involved in leisure activities: seven hours actively watching television, three hours reading, two in more active pursuits like jogging, making music, or bowling, and seven hours in social activities such as going to parties, seeing movies, or entertaining family and friends. The remaining fifty to sixty hours that an American is awake each week are spent in maintenance activities like eating, traveling to and from work, shopping, cooking, washing up, and fixing things; or in unstructured free time, like sitting alone and staring into space.

Although average Americans have plenty of free time, and ample access to leisure activities, they do not, as a result, experience flow often. Potentiality does not imply actuality, and quantity does not translate into quality. For example, TV watching, the single most often pursued leisure activity in the United States today, leads to the flow condition very rarely. In fact, working people achieve the flow experience—deep concentration, high and balanced challenges and skills, a sense of control and satisfaction—about four times as often on their jobs, proportionately, as they do when they are watching television.

One of the most ironic paradoxes of our time is this great availability of leisure that somehow fails to be translated into enjoyment. Compared to people living only a few generations ago, we have enormously greater opportunities to have a good time, yet there is no indication that we actually enjoy life more than our ancestors did. Opportunities alone, however, are not enough. We also need the skills to make use of them. And we need to know how to control consciousness—a skill that most people have not learned to cultivate. Surrounded by an astounding panoply of recreational gadgets and leisure choices, most of us go on being bored and vaguely frustrated.

This fact brings us to the second condition that affects whether an optimal experience will occur or not: an individual’s ability to restructure consciousness so as to make flow possible. Some people enjoy themselves wherever they are, while others stay bored even when confronted with the most dazzling prospects. So in addition to considering the external conditions, or the structure of flow activities, we need also to take into account the internal conditions that make flow possible.

It is not easy to transform ordinary experience into flow, but almost everyone can improve his or her ability to do so. While the remainder of this book will continue to explore the phenomenon of optimal experience, which in turn should help the reader to become more familiar with it, we shall now consider another issue: whether all people have the same potential to control consciousness; and if not, what distinguishes those who do it easily from those who don’t.

Some individuals might be constitutionally incapable of experiencing flow. Psychiatrists describe schizophrenics as suffering from anhedonia, which literally means “lack of pleasure.” This symptom appears to be related to “stimulus overinclusion,” which refers to the fact that schizophrenics are condemned to notice irrelevant stimuli, to process information whether they like it or not. The schizophrenic’s tragic inability to keep things in or out of consciousness is vividly described by some patients: “Things just happen to me now, and I have no control over them. I don’t seem to have the same say in things anymore. At times I can’t even control what I think about.” Or: “Things are coming in too fast. I lose my grip of it and get lost. I am attending to everything at once and as a result I do not really attend to anything.”

Unable to concentrate, attending indiscriminately to everything, patients who suffer from this disease not surprisingly end up unable to enjoy themselves. But what causes stimulus overinclusion in the first place?

Part of the answer probably has to do with innate genetic causes. Some people are just temperamentally less able to concentrate their psychic energy than others. Among schoolchildren, a great variety of learning disabilities have been reclassified under the heading of “attentional disorders,” because what they have in common is lack of control over attention. Although attentional disorders are likely to depend on chemical imbalances, it is also very likely that the quality of childhood experience will either exacerbate or alleviate their course. From our point of view, what is important to realize is that attentional disorders not only interfere with learning, but effectively rule out the possibility of experiencing flow as well. When a person cannot control psychic energy, neither learning nor true enjoyment is possible.

A less drastic obstacle to experiencing flow is excessive self-consciousness. A person who is constantly worried about how others will perceive her, who is afraid of creating the wrong impression, or of doing something inappropriate, is also condemned to permanent exclusion from enjoyment. So are people who are excessively self-centered. A self-centered individual is usually not self-conscious, but instead evaluates every bit of information only in terms of how it relates to her desires. For such a person everything is valueless in itself. A flower is not worth a second look unless it can be used; a man or a woman who cannot advance one’s interests does not deserve further attention. Consciousness is structured entirely in terms of its own ends, and nothing is allowed to exist in it that does not conform to those ends.

Although a self-conscious person is in many respects different from a self-centered one, neither is in enough control of psychic energy to enter easily into a flow experience. Both lack the attentional fluidity needed to relate to activities for their own sake; too much psychic energy is wrapped up in the self, and free attention is rigidly guided by its needs. Under these conditions it is difficult to become interested in intrinsic goals, to lose oneself in an activity that offers no rewards outside the interaction itself.

Attentional disorders and stimulus overinclusion prevent flow because psychic energy is too fluid and erratic. Excessive self-consciousness and self-centeredness prevent it for the opposite reason: attention is too rigid and tight. Neither extreme allows a person to control attention. Those who operate at these extremes cannot enjoy themselves, have a difficult time learning, and forfeit opportunities for the growth of the self. Paradoxically, a self-centered self cannot become more complex, because all the psychic energy at its disposal is invested in fulfilling its current goals, instead of learning about new ones.

The impediments to flow considered thus far are located within the individual himself. But there are also many powerful environmental obstacles to enjoyment. Some of these are natural, some social in origin. For instance, one would expect that people living in the incredibly harsh conditions of the arctic regions, or in the Kalahari desert, would have little opportunity to enjoy their lives. Yet even the most severe natural conditions cannot entirely eliminate flow. The Eskimos in their bleak, inhospitable lands learned to sing, dance, joke, carve beautiful objects, and create an elaborate mythology to give order and sense to their experiences. Possibly the snow dwellers and the sand dwellers who couldn’t build enjoyment into their lives eventually gave up and died out. But the fact that some survived shows that nature alone cannot prevent flow from happening.

The social conditions that inhibit flow might be more difficult to overcome. One of the consequences of slavery, oppression, exploitation, and the destruction of cultural values is the elimination of enjoyment. When the now extinct natives of the Caribbean islands were put to work in the plantations of the conquering Spaniards, their lives became so painful and meaningless that they lost interest in survival, and eventually ceased reproducing. It is probable that many cultures disappeared in a similar fashion, because they were no longer able to provide the experience of enjoyment.

Two terms describing states of social pathology apply also to conditions that make flow difficult to experience: anomie and alienation. Anomie—literally, “lack of rules”—is the name the French sociologist Emile Durkheim gave to a condition in society in which the norms of behavior had become muddled. When it is no longer clear what is permitted and what is not, when it is uncertain what public opinion values, behavior becomes erratic and meaningless. People who depend on the rules of society to give order to their consciousness become anxious. Anomic situations might arise when the economy collapses, or when one culture is destroyed by another, but they can also come about when prosperity increases rapidly, and old values of thrift and hard work are no longer as relevant as they had been.

Alienation is in many ways the opposite: it is a condition in which people are constrained by the social system to act in ways that go against their goals. A worker who in order to feed himself and his family must perform the same meaningless task hundreds of times on an assembly line is likely to be alienated. In socialist countries one of the most irritating sources of alienation is the necessity to spend much of one’s free time waiting in line for food, for clothing, for entertainment, or for endless bureaucratic clearances. When a society suffers from anomie, flow is made difficult because it is not clear what is worth investing psychic energy in; when it suffers from alienation the problem is that one cannot invest psychic energy in what is clearly desirable.

It is interesting to note that these two societal obstacles to flow, anomie and alienation, are functionally equivalent to the two personal pathologies, attentional disorders and self-centeredness. At both levels, the individual and the collective, what prevents flow from occurring is either the fragmentation of attentional processes (as in anomie and attentional disorders), or their excessive rigidity (as in alienation and self-centeredness). At the individual level anomie corresponds to anxiety, while alienation corresponds to boredom.

Neurophysiology and Flow

Just as some people are born with better muscular coordination, it is possible that there are individuals with a genetic advantage in controlling consciousness. Such people might be less prone to suffer from attentional disorders, and they may experience flow more easily.

Dr. Jean Hamilton’s research with visual perception and cortical activation patterns lends support to such a claim. One set of her evidence is based on a test in which subjects had to look at an ambiguous figure (a Necker cube, or an Escher-type illustration that at one point seems to be coming out of the plane of the paper toward the viewer and the next moment seems to recede behind the plane), and then perceptually “reverse” it—that is, see the figure that juts out of the surface as if it were sinking back, and vice versa. Dr. Hamilton found that students who reported less intrinsic motivation in daily life needed on the average to fix their eyes on more points before they could reverse the ambiguous figure, whereas students who on the whole found their lives more intrinsically rewarding needed to look at fewer points, or even only a single point, to reverse the same figure.

These findings suggest that people might vary in the number of external cues they need to accomplish the same mental task. Individuals who require a great deal of outside information to form representations of reality in consciousness may become more dependent on the external environment for using their minds. They would have less control over their thoughts, which in turn would make it more difficult for them to enjoy experience. By contrast, people who need only a few external cues to represent events in consciousness are more autonomous from the environment. They have a more flexible attention that allows them to restructure experience more easily, and therefore to achieve optimal experiences more frequently.

In another set of experiments, students who did and who did not report frequent flow experiences were asked to pay attention to flashes of lights or to tones in a laboratory. While the subjects were involved in this attentional task, their cortical activation in response to the stimuli was measured, and averaged separately for the visual and auditory conditions. (These are called “evoked potentials.”) Dr. Hamilton’s findings showed that subjects who reported only rarely experiencing flow behaved as expected: when responding to the flashing stimuli their activation went up significantly above their baseline level. But the results from subjects who reported flow frequently were very surprising: activation decreased when they were concentrating. Instead of requiring more effort, investment of attention actually seemed to decrease mental effort. A separate behavioral measure of attention confirmed that this group was also more accurate in a sustained attentional task.

The most likely explanation for this unusual finding seems to be that the group reporting more flow was able to reduce mental activity in every information channel but the one involved in concentrating on the flashing stimuli. This in turn suggests that people who can enjoy themselves in a variety of situations have the ability to screen out stimulation and to focus only on what they decide is relevant for the moment. While paying attention ordinarily involves an additional burden of information processing above the usual baseline effort, for people who have learned to control consciousness focusing attention is relatively effortless, because they can shut off all mental processes but the relevant ones. It is this flexibility of attention, which contrasts so sharply with the helpless overinclusion of the schizophrenic, that may provide the neurological basis for the autotelic personality.

The neurological evidence does not, however, prove that some individuals have inherited a genetic advantage in controlling attention and therefore experiencing flow. The findings could be explained in terms of learning rather than inheritance. The association between the ability to concentrate and flow is clear; it will take further research to ascertain which one causes the other.

The Effects of the Family on the Autotelic Personality

A neurological advantage in processing information may not be the only key to explaining why some people have a good time waiting at a bus station while others are bored no matter how entertaining their environment is. Early childhood influences are also very likely factors in determining whether a person will or will not easily experience flow.

There is ample evidence to suggest that how parents interact with a child will have a lasting effect on the kind of person that child grows up to be. In one of our studies conducted at the University of Chicago, for example, Kevin Rathunde observed that teenagers who had certain types of relationship with their parents were significantly more happy, satisfied, and strong in most life situations than their peers who did not have such a relationship. The family context promoting optimal experience could be described as having five characteristics. The first one is clarity: the teenagers feel that they know what their parents expect from them—goals and feedback in the family interaction are unambiguous. The second is centering, or the children’s perception that their parents are interested in what they are doing in the present, in their concrete feelings and experiences, rather than being preoccupied with whether they will be getting into a good college or obtaining a well-paying job. Next is the issue of choice: children feel that they have a variety of possibilities from which to choose, including that of breaking parental rules—as long as they are prepared to face the consequences. The fourth differentiating characteristic is commitment, or the trust that allows the child to feel comfortable enough to set aside the shield of his defenses, and become unselfconsciously involved in whatever he is interested in. And finally there is challenge, or the parents’ dedication to provide increasingly complex opportunities for action to their children.

The presence of these five conditions made possible what was called the “autotelic family context,” because they provide an ideal training for enjoying life. The five characteristics clearly parallel the dimensions of the flow experience. Children who grow up in family situations that facilitate clarity of goals, feedback, feeling of control, concentration on the task at hand, intrinsic motivation, and challenge will generally have a better chance to order their lives so as to make flow possible.

Moreover, families that provide an autotelic context conserve a great deal of psychic energy for their individual members, thus making it possible to increase enjoyment all around. Children who know what they can and cannot do, who do not have to constantly argue about rules and controls, who are not worried about their parents’ expectations for future success always hanging over their heads, are released from many of the attentional demands that more chaotic households generate. They are free to develop interests in activities that will expand their selves. In less well-ordered families a great deal of energy is expended in constant negotiations and strife, and in the children’s attempts to protect their fragile selves from being overwhelmed by other people’s goals.

Not surprisingly, the differences between teenagers whose families provided an autotelic context and those whose families did not were strongest when the children were at home with the family: here those from an autotelic context were much more happy, strong, cheerful, and satisfied than their less fortunate peers. But the differences were also present when the teenagers were alone studying, or in school: here, too, optimal experience was more accessible to children from autotelic families. Only when teenagers were with their friends did the differences disappear: with friends both groups felt equally positive, regardless of whether the families were autotelic or not.

It is likely that there are ways that parents behave with babies much earlier in life that will also predispose them to find enjoyment either with ease or with difficulty. On this issue, however, there are no long-term studies that trace the cause-and-effect relationships over time. It stands to reason, however, that a child who has been abused, or who has been often threatened with the withdrawal of parental love—and unfortunately we are becoming increasingly aware of what a disturbing proportion of children in our culture are so mistreated—will be so worried about keeping his sense of self from coming apart as to have little energy left to pursue intrinsic rewards. Instead of seeking the complexity of enjoyment, an ill-treated child is likely to grow up into an adult who will be satisfied to obtain as much pleasure as possible from life.

The traits that mark an autotelic personality are most clearly revealed by people who seem to enjoy situations that ordinary persons would find unbearable. Lost in Antarctica or confined to a prison cell, some individuals succeed in transforming their harrowing conditions into a manageable and even enjoyable struggle, whereas most others would succumb to the ordeal. Richard Logan, who has studied the accounts of many people in difficult situations, concludes that they survived by finding ways to turn the bleak objective conditions into subjectively controllable experience. They followed the blueprint of flow activities. First, they paid close attention to the most minute details of their environment, discovering in it hidden opportunities for action that matched what little they were capable of doing, given the circumstances. Then they set goals appropriate to their precarious situation, and closely monitored progress through the feedback they received. Whenever they reached their goal, they upped the ante, setting increasingly complex challenges for themselves.

Christopher Burney, a prisoner of the Nazis who had spent a long time in solitary confinement during World War II, gives a fairly typical example of this process:

If the reach of experience is suddenly confined, and we are left with only a little food for thought or feeling, we are apt to take the few objects that offer themselves and ask a whole catalogue of often absurd questions about them. Does it work? How? Who made it and of what? And, in parallel, when and where did I last see something like it and what else does it remind me of? . . . So we set in train a wonderful flow of combinations and associations m our minds, the length and complexity of which soon obscures its humble starting-point. . . . My bed, for example, could be measured and roughly classified with school beds or army beds. . . . When I had done with the bed, which was too simple to intrigue me long, I felt the blankets, estimated their warmth, examined the precise mechanics of the window, the discomfort of the toilet . . . computed the length and breadth, the orientation and elevation of the cell [italics added].

Essentially the same ingenuity in finding opportunities for mental action and setting goals is reported by survivors of any solitary confinement, from diplomats captured by terrorists, to elderly ladies imprisoned by Chinese communists. Eva Zeisel, the ceramic designer who was imprisoned in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison for over a year by Stalin’s police, kept her sanity by figuring out how she would make a bra out of materials at hand, playing chess against herself in her head, holding imaginary conversations in French, doing gymnastics, and memorizing poems she composed. Alexander Solzhenitsyn describes how one of his fellow prisoners in the Lefortovo jail mapped the world on the floor of the cell, and then imagined himself traveling across Asia and Europe to America, covering a few kilometers each day. The same “game” was independently discovered by many prisoners; for instance Albert Speer, Hitler’s favorite architect, sustained himself in Spandau prison for months by pretending he was taking a walking trip from Berlin to Jerusalem, in which his imagination provided all the events and sights along the way.

An acquaintance who worked in United States Air Force intelligence tells the story of a pilot who was imprisoned in North Vietnam for many years, and lost eighty pounds and much of his health in a jungle camp. When he was released, one of the first things he asked for was to play a game of golf. To the great astonishment of his fellow officers he played a superb game, despite his emaciated condition. To their inquiries he replied that every day of his imprisonment he imagined himself playing eighteen holes, carefully choosing his clubs and approach and systematically varying the course. This discipline not only helped preserve his sanity, but apparently also kept his physical skills well honed.

Tollas Tibor, a poet who spent several years in solitary confinement during the most repressive phases of the Hungarian communist regime, says that in the Visegrád jail, where hundreds of intellectuals were imprisoned, the inmates kept themselves occupied for more than a year by devising a poetry translation contest. First, they had to decide on the poem to translate. It took months to pass the nominations around from cell to cell, and several more months of ingenious secret messages before the votes were tallied. Finally it was agreed that Walt Whitman’s O Captain! My Captain! was to be the poem to translate into Hungarian, partly because it was the one that most of the prisoners could recall from memory in the original English. Now began the serious work: everyone sat down to make his own version of the poem. Since no paper or writing tool was available, Tollas spread a film of soap on the soles of his shoe, and carved the letters into it with a toothpick. When a line was learned by heart, he covered his shoe with a new coating of soap. As the various stanzas were written, they were memorized by the translator and passed on to the next cell. After a while, a dozen versions of the poem were circulating in the jail, and each was evaluated and voted on by all the inmates. After the Whitman translation was adjudicated, the prisoners went on to tackle a poem by Schiller.

When adversity threatens to paralyze us, we need to reassert control by finding a new direction in which to invest psychic energy, a direction that lies outside the reach of external forces. When every aspiration is frustrated, a person still must seek a meaningful goal around which to organize the self. Then, even though that person is objectively a slave, subjectively he is free. Solzhenitsyn describes very well how even the most degrading situation can be transformed into a flow experience: “Sometimes, when standing in a column of dejected prisoners, amidst the shouts of guards with machine guns, I felt such a rush of rhymes and images that I seemed to be wafted overhead. . . . At such moments I was both free and happy. . . . Some prisoners tried to escape by smashing through the barbed wire. For me there was no barbed wire. The head count of prisoners remained unchanged but I was actually away on a distant flight.”

Not only prisoners report these strategies for wresting control back to their own consciousness. Explorers like Admiral Byrd, who once spent four cold and dark months by himself in a tiny hut near the South Pole, or Charles Lindbergh, facing hostile elements alone on his transatlantic flight, resorted to the same steps to keep the integrity of their selves. But what makes some people able to achieve this internal control, while most others are swept away by external hardships?

Richard Logan proposes an answer based on the writings of many survivors, including those of Viktor Frankl and Bruno Bettelheim, who have reflected on the sources of strength under extreme adversity. He concludes that the most important trait of survivors is a “nonself-conscious individualism,” or a strongly directed purpose that is not self-seeking. People who have that quality are bent on doing their best in all circumstances, yet they are not concerned primarily with advancing their own interests. Because they are intrinsically motivated in their actions, they are not easily disturbed by external threats. With enough psychic energy free to observe and analyze their surroundings objectively, they have a better chance of discovering in them new opportunities for action. If we were to consider one trait a key element of the autotelic personality, this might be it. Narcissistic individuals, who are mainly concerned with protecting their self, fall apart when the external conditions turn threatening. The ensuing panic prevents them from doing what they must do; their attention turns inward in an effort to restore order in consciousness, and not enough remains to negotiate outside reality.

Without interest in the world, a desire to be actively related to it, a person becomes isolated into himself. Bertrand Russell, one of the greatest philosophers of our century, described how he achieved personal happiness: “Gradually I learned to be indifferent to myself and my deficiencies; I came to center my attention increasingly upon external objects: the state of the world, various branches of knowledge, individuals for whom I felt affection.” There could be no better short description of how to build for oneself an autotelic personality.

In part such a personality is a gift of biological inheritance and early upbringing. Some people are born with a more focused and flexible neurological endowment, or are fortunate to have had parents who promoted unselfconscious individuality. But it is an ability open to cultivation, a skill one can perfect through training and discipline. It is now time to explore further the ways this can be done.