Crisps began knocking around British pubs shortly after the First World War, when Frank Smith and his wife started bagging them up in their Cricklewood garage. For decades, Smiths was the country’s only major crisp company, on the stock market since 1929 and corporate to a fault. Up and down the country, though, nearly 800 tiny backroom outfits were nibbling at their heels, many started by grocers and butchers augmenting their tough, ration-hobbled trade with a cheap sideline assisted by a demob grant.

Initially, production was crude and dirty, with crisps fried in batches in much the same way as fish suppers. Toiling workers became so saturated with oil fumes that their bosses had to lay on special buses to take them home, to keep public transport free of the stench of stale chip oil. That all changed in the late 1950s when newfangled continuous fryers were imported from the States, Tudor being the first recipients in ‘57. These automated wonders could provide a constant stream of crisps, at the rate of eight tons of spuds an hour. British crisps were about to become big business.

The main challenge to the Smiths monopoly was Scottish outfit Golden Wonder, started by William Alexander as a sideline to his bakery business. They gained plenty of local kudos, but really took off when they were bought by Imperial Tobacco in 1961. The new Golden Wonder’s objective was nothing less than national domination. While Smiths were still farting around with booklets wherein fictional radio matriarch Doris Archer doled out recipes for scones and fudge featuring a handful of ‘delicious Smiths potato crisps, crushed to farthing size’, Golden Wonder went for broke. They built three new crisp factories including the ‘world’s biggest’ in Corby, and replaced old-fashioned waxed paper bags with a long tube of glossy cellophane. These were filled with crisps, sealed and snipped off into instant, moisture-proof packs with reassuring little windows onto the product itself: ‘Crackle-fresh!’ as children’s entertainer Mr Pastry put it in the adverts.

Golden Wonder’s ‘crackle-fresh’ flavours, circa 1978.

Noting that Smiths had the traditional crisp market – old blokes in pubs – locked down, the Wonder team shipped their glossy offerings off to grocers, supermarkets and newsagents. What was a dreary post-war meat substitute became a fun family snack. Smiths’ management reeled under the weight of unprecedented competition. Imperial Tobacco even tried to buy them up too, but the Monopolies Commission weren’t having it. The ‘70s began with Smiths knocked into second place for the first time in crisp history.

Britain’s third biggest crisp maker was, of course ... Meredith and Drew. Hardly a household name, but they were behind nearly all the own-brand supermarket crisps of the day, as well as their own Crispi Crisps which, after 1975, were gradually brought in line with their nut-based sister brand KP. Regional manufacturers were being incorporated left, right and centre. Chipmunk Crisps were bought from their parent company Liebig, makers of Oxo, and assimilated into Golden Wonder in 1969. Tyneside’s venerable Tudor had been a Smiths subsidiary since 1962, while Burton’s of Doncaster (makers of Crown and XL Crisps) and Lancashire’s Rishy were absorbed by the colossal Associated British Foods Group. Oh, and US monolith Frito Lay sought a bit of British action by buying up tiny Scottish firm Crimpy Crisps, but nothing came of that.

A cheek-pouch filler for Chipmunk (1972). Smith’s forelock-tugging flavour (1981).

Through all this upheaval a few indies held out, like Bradford’s dauntless Seabrook Crisps, and an operation that spent the 1970s slowly but surely expanding from its command centre at 4 Cheapside, Leicester.

It’s fair to say no one saw Walkers coming. Instigated in 1949 by butcher Henry Walker and sandwiched geographically between the Smiths and Golden Wonder head offices, they eschewed going national in favour of slowly but steadily conquering their local market. By 1973 they accounted for over half the crisps sold in the Midlands, which was a lot of crisps. Walkers also renounced kid-friendly cartoon gimmicks. Not for them the unctuous, Nimmo-voiced likes of the KP friars, or the funny little bloke in the tam-o’-shanter who decorated packets of Golden Wonder. Nor did they try to compete with the likes of Tudor in the novelty flavour market. Slow, sensible and steady-as-she-goes was their motto.

Walkers’ ‘confuse an alcoholic’ campaign, circa 1980.

The market for crisps was expanding as never before, but it was a choppy ride. Potato famines were, predictably, a dent in profits. The introduction of the breathalyser in 1967 hit pub sales so badly that Chipmunk had to put 200 workers on short time. Worse still, in 1974 Denis Healey stuck VAT on crisps, leading a Daily Mirror consumer report to conclude that ‘the price per pound often puts these products in the steak class.’ Novelties designed to distract customers from the ludicrous prices came and went. While the big boys knocked themselves out to stay on top, Walkers just carried on soberly divvying up the sales areas, sweet-talking the country’s cash and carries and plonking the odd Guinness world record on the backs of the packs.

Walkers were bought out by Shredded Wheat giant Nabisco. Soon afterwards, they swallowed up Smiths as well, and so began the long, painful process of Smiths and Tudor gradually vanishing under the unstoppable might of their former rival. Golden Wonder became distracted by their Pot Noodle, which was suddenly very successful, and then just as suddenly wasn’t. Strikes and a factory fire didn’t help matters. They never fully recovered their old pep. At the end of the decade, Walkers were sold on to the even mightier Pepsico, and the rest is jug-eared, Match of the Day-presenting, crisp-thieving history.

The crisp world is a ruthless commercial battleground, and no one should begrudge Walkers their hard-won success, but despite your Sensations, World Cup limited editions and Comic Relief flavour-related hilarity, it’s hard not to shed a tear for that overcrowded, cartoon-festooned, pickled onion flavoured pantechnicon that was the 1970s crisp world. But that’s probably the nostalgia talking. Or maybe the sodium benzoate.

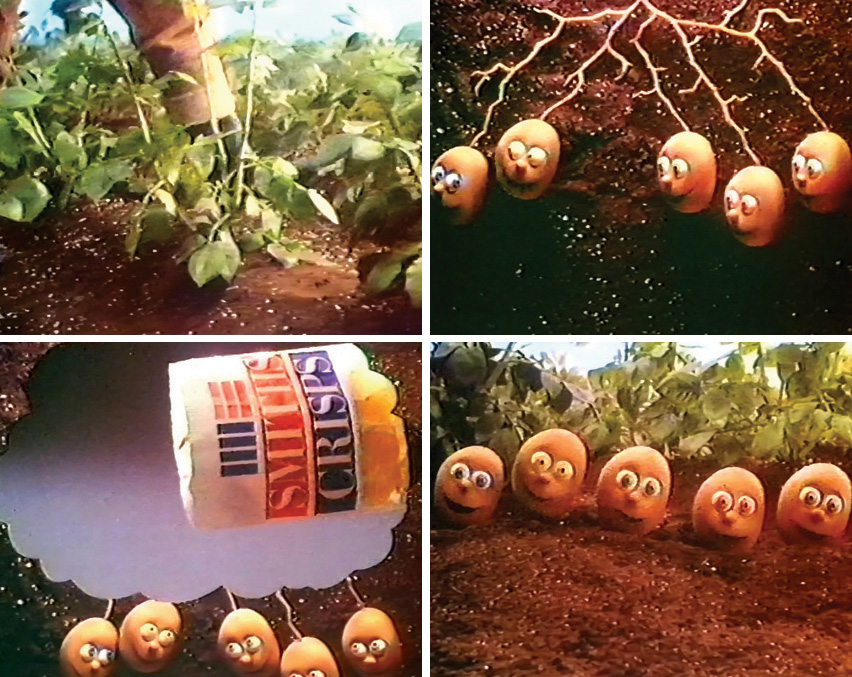

Try eating these on the streets of Belfast! Murphy’s Crisps, circa 1974. Stop-motion spuds welcome oblivion for Smith’s, circa 1982.