It’s not clear who came up with the first flavoured crisps (ask any crisp company of sufficiently advanced years and they’ll say, ‘It was us’), but Ireland’s Tayto have a better claim than most with their early-doors cheese and onion circa 1957, with Golden Wonder following suit soon after. Smiths, slow on the uptake but eventually sensing an emerging market, countered with salt ‘n’ vinegar, tested first by their Geordie subsidiary Tudor, and launched nationally in 1967. Though they did not know it, both companies had fired the first rounds in a battle that would become a two-decade-long flavour war. By the end of the 1960s, the crisp market had doubled.

First to notice was – who else? – renowned architecture and design critic Reyner Banham, the man who had helped define early modernism, brutalism and industrial megastructure. An unlikely commentator on the common ‘tater, possibly, but an earnest one nonetheless. In a prescient 1970 New Society magazine piece entitled ‘The Crisp at the Crossroads’, no doubt knocked out over a weekend, he correctly identified a trend towards ‘sundry aromas arising from the secret kitchens of [crisp companies’] research and development departments’. Later that year, the British Society of Flavourists formed, uniting food technologists and commercial enterprise in a common interest: giving every child in Britain really stinky breath.

It worked! In 1971, flavoured crisps accounted for 55 per cent of the industry’s total sales. Tudor, for one, started to treat their consumers like some unofficial focus group, as they searched for new natural and artificial flavours to help widen market penetration. ‘Special request’ edition packets were introduced, apparently due to public demand and for overtly limited periods. Golden Wonder, meanwhile, were all over the shop. A baked bean flavour was loudly trumpeted, the product of ‘a year’s research and development’. It soon turned out a year wasn’t long enough. More successful was a branded Oxo flavour (though that too quickly faced opposition from Smiths’ Bovril flavour). Where Golden Wonder did excel was in the savoury snack category, a fact even arch-rivals Smiths had to accept begrudgingly in the face of Wotsits’ domination. Non-potato vegetable proteins were cheaper and more plentiful, plus they could be aerated (thus filling a packet for less) and they suited the more esoteric flavours better than their subterranean counterparts. For inspiration, all Golden Wonder needed to do was look east.

Make mine meat! The manly taste of Smith’s circa 1974, and Golden Wonder (1972).

Enter, in 1974, to the sound of a gong and that racist xylophone riff, Kung Fuey, ‘crunchy corn and potato balls with an unusual bacon and mushroom flavour’. Golden Wonder’s Oriental opportunism paid dividends, riding the crest of a wave of martial arts popularity: kids were already karate-chopping piles of wood and trying to kick down walls barefoot. Now TV ad breaks were filled with Chinese stereotypes doing the same in the name of snack food (leading one copycat eight-year-old in Acton to lose a toenail). Kung Fuey’s yellow-packed, inauthentically flavoured original was joined later by a black-clad cheese and ham variety, though this was greeted less enthusiastically and, like Bruce Lee before them, the snack went the way of the dragon.

British beef (1972) meets Kung Fuey (1975).

Other companies also took their starchy corn, wheat and potato creations to the takeaway in search of a taste sensation – Smiths’ Chinese flavour Quavers sort of approximated spicy beef, KP Skips dipped into a sweet ‘n’ sour sauce, and even Benson’s attempted a rudimentary prawn cracker – but the real winners were to be found wrapped in newspaper down the good old British chippy. Smiths’ much imitated Chipsticks took a patriotic approach, with packet design and TV advertising that riffed on saucy seaside postcard humour (initially aimed at an adult audience with lashings of innuendo but soon softened to kid-friendly Punch and Judy show standards).

Oily, yet moreish, these flaky, puffed-up sticks of potato and maize concealed often intense and acerbic flavours, the salt ‘n’ vinegar variety being particularly nasal. Tudor’s version, Saucy Fries, mimicked the similarly piquant tang of a bottle of HP whereas, puzzlingly, Americans would have been more familiar with Andy Capp’s Pub Fries, the distributor (Goodmark Foods) feeling that the Hartlepool-based layabout made for a good mascot. At least they weren’t Mini Chips, KP’s appallingly dry, solid spikes of potato, deemed so bland by marketers that they were sold under the tagline, ‘You can hear the taste’. When your snack product cannot be enjoyed without calling upon the assistance of another sense organ, you know it’s in trouble.

Good old seaside fun from Chipsticks circa 1978, and good old casual racism from Quavers (1977).

By the late ’70s, the boffins in the food science labs were coming into their own. Chicken ‘n’ sage, fried onion and curry flavoured crisps were commonplace. Golden Wonder’s crispy bacon flavour (created by the controlled burning of hickory sawdust) was among their top sellers, along with beef ‘n’ onion and sausage ‘n’ tomato, while a super-confident Smiths were game enough to risk a ‘mystery flavour’ for their astrology-themed snack, Zodiacs. In 1979 United Biscuits claimed they had over 200 flavours ‘under review’ for possible use in their crisp range, and the other big players were undoubtedly juggling similar numbers.

Out of the unknown and into the gob – Smith’s Zodiacs (1979). Dubious rejuvenation claims ahoy, circa 1987.

Many of them now outsourced their seasoning requirements to the likes of Glentham International of Twickenham (chicken tandoori, sweet and sour pork), Dinoval (Bolognese sauce, hamburger) or Griffith Laboratories of Derby (the inventors of salt ‘n’ vinegar, so they claimed, although how hard could that have been?). The first of these was about to drop a flavour bomb so big it would change the fried potato landscape forever. All thanks to a supercilious TV chef.

Fanny Cradock started the decade as the queen of British cuisine and ended it as a laughing stock. The success of her long-running cookery series had been undermined by one dyspeptic appearance as a celebrity expert on The Big Time, a documentary-cum-talent show for the Beeb. For years, however, Cradock was known as the champion of a certain sophisticated signature dish that would eventually become a byword for 1970s naffness.

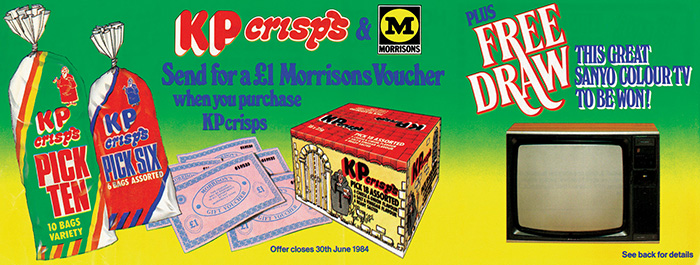

Shouldn’t this offer have been on packets of McCoys? (1986). The acme of deep-fried daintiness, KP Skips (1976).

The prawn cocktail, transplanted from Las Vegas surf ‘n’ turf buffets, via Berni Inn and Abigail’s Party, rose to epicurean eminence under her stewardship. Yet it wasn’t until 1980 that Glentham managed to capture perfectly its seafood-in-a-marie-rose-sauce essence. Associations with retro kitsch didn’t stop Smiths, Tudor and Golden Wonder releasing rival flavours within months of each other, and opening the floodgates for the prawn cocktail plague. KP Skips rebranded themselves as ‘Britain’s daintiest snack’ with ‘the flavour of the moment’ and brought in gargantuan professional wrestler Giant Haystacks to act the ponce on TV. They never looked back.

Over in Bradford, a company that would later become synonymous with unusual and strong flavours had just relocated to a new factory in Duncombe Street. Seabrook Crisps (so named after a local photographer’s shop misspelled owner Charles Brook’s name) pioneered the use of sunflower oil and sea salt, as well as grammatically challenged slogans (‘More’ – Than A ‘Snack’). From the mid-’80s their roster boasted ‘Wuster’ sauce, Canadian ham, roast garlic, sweetcorn, and bacon ‘n’ brown sauce among the usual array of onion, cheese and chicken flavours.

The KP friars swap pick ‘n’ mix belief for pick ‘n’ mix beef.

‘In what way is this not just, you know, “cheese”?’ Walkers leap aboard the ‘finicky flavours’ bandwagon (1989).

Resolutely northern, their ongoing success gave the lie to the theory that only namby-pamby southerners would approach anything a bit fancy. Smiths remained poker-faced and commissioned some research into regional tastes: ‘Northerners prefer barbecue chicken and other meaty flavours’ they stated baldly. ‘In the Midlands, cheese crisps take over, and down south the milder tastes are preferred.’

Another Seabrook advance was the use of the ‘crinkle cut’ for their crisps. The theory went that crinkles would enhance the flavour by increasing the surface area of each individual crisp, thus allowing more contact between tongue and titbit. In practice it was nothing more than a gimmick. KP’s Crinkles launched in 1980, with an offer to obtain an ‘I’m a KP Crinkle-ologist’ badge that might just as well have read ‘Please kick seven bells out of me’. Smiths’ Crinkle Cut copycats claimed ‘From now on ordinary crisps will seem a bit flat’, which was a bit rich coming from the makers of Square Crisps.

Flavour experimentation waned as the ‘90s loomed ahead, with novelty crisps rising and falling from favour in quick succession. KP Pizza crisps, apparently devised by clerical cartoon frontman ‘Brother Angelo’, were swiftly carried away to join the choir invisible. Walkers’ spicy sausage flavour, the company’s one ambitious attempt at something out of the ordinary, also long exceeded their sell-by date. And the less said about Benson’s XL corned beef crisps the better. In 1991 The Times reported that the UK was home to forty-four different flavours of crisp, more than any other country, and an unsustainable high for the snack industry. The torch eventually passed back to Tudor (‘the only crisp worth its salt’) who introduced the fried potato/chocolate combo in – where else? – Scotland, sounding the death knell for the tasteful crunch and opening the door for the ‘gourmet chip’.

Unnecessary inverted commas not ‘pictured’. Seabrook’s crisps circa 1984.

Britain’s favourite flavours faced assault-n-vinegar on two fronts. While American atrocities of the sweet chilli, nacho cheese and ‘cool ranch’ variety drifted lazily across the Atlantic on a Frito-Lay Lilo, further battle lines were being drawn in Brussels. The tabloids fingered German industry commissioner Martin Bangemann, ‘the Eurocrat determined to ban our flavoured crisps’ under a Common Market directive restricting the use of artificial additives. The British response was clear: you can straighten our bananas and stop us smacking our kids, but keep your hands off our sacred cheese ‘n’ onion, Fritz! It seemed that Reyner Banham had been right all along. For him, as for all Britons, the crisp was a ‘ritual substitute for solid food, the kind of token victual that ancient peoples buried with their dead, the nutriment of angels rather than mortal flesh’. Good luck with those Scampi Fries in heaven, St Peter.