The best thing about savoury snacks, from a kid’s point of view, is the independence they represent. You buy them yourself with your own money, and eat them where and when you fancy (or at least can get away with). Best of all, they bear little or no relation to all that boring old ‘proper’ food your mum tries to shove down your gullet when you go home. If the flavours don’t actually taste anything like their descriptions, that’s surely a bonus. But snack firms have another trick up their sleeves to distance their liberating bags of fun from the everyday meat and two veg grind: the corn or potato puff, warped into a pleasingly wacky shape.

Large-scale corn snack cookery is nothing like any cuisine you’ll have encountered. For one thing, it has a strangely sadomasochistic vocabulary all of its own involving twin-screw extrusion cookers, kneading zones, surge bins and feeder shafts. Essentially, the powdered potato or corn meal is mixed with water, squeezed through a heated tube by a long screw, cooked at super-high temperatures to create that mouth-melting puffy texture, forced through a metal die cut in whatever shape you choose, and cut to length by rotating knives. The resulting ‘collette’ falls into a big spinning drum to be fried and coated with whatever giddy numerical flavourings Brussels will allow, along with lashings of – as the accepted industry term has it – liquid cheese slurry. It’s a maize-based abattoir, really. Best not to think about it.

Years of the dragon – spicy tomato (1978) and original (1975) Walker’s Snaps.

Still, what the nine-year-old eye doesn’t see, the good folk of Ashby-de-la-Zouch get away with, and such munchable mutations became big sellers during the early 1970s. Phase one consisted of two basic shapes: the puffed-up cheesy lozenge, as exemplified by Golden Wonder’s Wotsits of 1971, and the flattened shape that curled up at the edges, initiated by Smiths in 1968 with the Quaver, and enhanced by Walkers in 1975 for a rare excursion into shaped snacks, the Snap. The adverts for Snaps handily summed up the sensory experience of the ideal corn snack, laid out by the eponymous Harry H. Corbett-voiced dragon as consisting of, a) the crunch, b) the ‘melt in your maahf’ and c) the flavour explosion. Despite this canny technical dissection of the snacking experience, Walkers never ventured too far into multiform manufacture, the relatively straightforward flattened puffery of Say Cheese and Bitza Pizza being as daring as they got.

For everyone else, the game was afoot, and phase two was more topologically adventurous. For this, a more dense form of corn pulp allowed a greater degree of control, and the resulting snacks were crunchier. Simplest of these was the ring, pioneered in 1970 with Smiths Onyums, onion rings in maize form with an off-the-peg cartoon Frenchman on the pack, beating Golden Wonder Ringos to the shelves by almost three years, and KP’s perenially popular finger-sized Hula Hoops by two. Last, and very possibly least, KP Griddles (‘with the holes in the middles!’) rolled up at the end of the decade.

Snack geometry basics – Smith’s Quavers (1968) and KP Griddles (1982).

As shapes became more ambitious, their quasi-geometric descriptions began to cause confusion. Smiths released their ground-breaking spiral-shaped potato puffs in 1974, heralding a new development which, as they modestly put it, ‘could be as important as the invention of crisps’. Whether you called them Quirls or Twists depended, initially, on where in the country you bought them, until everyone settled down with the latter name. Things were simpler at the start of the decade when their intricately lattice-shaped Chekkers were called the same thing countrywide. Incidentally, the lattice shape was, for some reason, something of an obsession with snack companies, reaching its zenith in 1981 with KP’s finely wrought Wickers.

These miniature wickerwork envelopes in modish prawn cocktail flavour were promoted, oddly, by adverts featuring an all-singing, all-dancing medieval court. This fierce high-tech one-upmanship soon established the shaped snack market as the Formula One of the tuck shop.

Snacketeers enlisted the help of good old industrial food dye to help define their vague wobbly forms. In 1975 Smiths showed off their bacon rasher-aping product Frazzles, blessed with an ‘exciting flavour, superior to that of any bacon flavour product’ by adding little brown streaks of Lord-knows-what concentrate.

The Fabergé egg of moulded snacks, KP Wickers (1981).

It wasn’t just the industry giants who were screwing that corn pulp. Tudor cooked up their knobbly Rustlers and Tags, and in 1972 their cheesy Rolls were being touted as ‘a technological breakthrough in snack food production’ – yes, there was a lot of this kind of talk – attaining unheard-of levels of melt-in-the-mouth bliss. ‘Mouthfeel’ was the daftly named but increasingly important quality that separated a light, fluffy savoury success from a rock-hard, misshapen catastrophe. Although one of the by-products of snack extrusion failure, namely the occasional lump of solid flavouring lurking at the bottom of the bag, became a prized delicacy among junior gourmets whose taste buds were living on borrowed time.

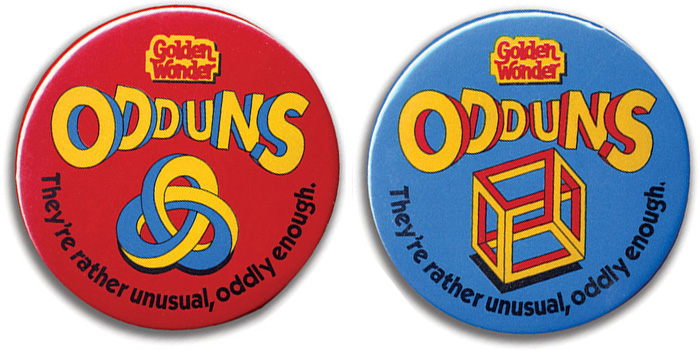

The culinary equivalent of Halford’s – a big bag of Nibb-it Wheelz (1986); the dimension-warping snackery of Golden Wonder Odduns (1983).

Once the basics of moulding were mastered, things got ambitious with a spate of representational realism. KP’s bacon flavour Whiz Wheels literally surfed the 1978 Zeitgeist by aping the little plastic cylinders to be found on those trendy new things called skateboards. They weren’t the first to make wheels. The good people of Tudor had beaten them to it by two years with their similarly spoked Forty Niners, and the cash and carries of the north groaned under the weight of gigantic, squirrel-adorned packs of the supersized Nibb-It Wheelz.

None of those wheels, however, would have got you very far by the time the packet was opened. The higher snack artisans aimed, the harder they fell when contents settled in transit. KP’s Outer Spacers were frequently scarred by some colossal intergalactic war that broke out halfway up the M6. Smiths’ Farmer Browns, a hopelessly over-ambitious farmyard miscellany promising ‘bags of moo, neigh, woof, baa and cock-a-doodle doo’, looked more like an assortment of fossils straight from the primeval sludge. Most unfortunate of all, the plucky little daredevils in a packet of KP Sky Divers were prone to all manner of horrendous injuries, suggesting a product recall at the parachute makers was in order. Perhaps the way to go was towards abstraction: Golden Wonder’s Atom Smashers were supposedly modelled on the contents of a particle accelerator, but looked suspiciously like bog-standard noughts and crosses to the physics-ignorant kid on the street.

Lunchbox meltdown with Golden Wonder Atom Smashers (1978); a free coroner’s report in every bag of KP Sky Divers (1980).

Golden Wonder ducked out of the novelty shape market in 1978, dismissing it as faddish, but looked at the sales figures for Smiths’ all-conquering Monster Munch and swiftly rethought. In 1983 they teamed up with DC Comics to launch Super Heroes: Spiderman and Superman symbols fully endorsed by the webslinger and man of steel. Golden Wonder fancied their chances, declaring Monster Munch to be ‘nearing the end of its product life’. They were rapidly proved wrong.

Excelsior emulsified by Golden Wonder Super Heroes (1980).

The early 1980s saw the high-water mark of snack diversity. As the more outlandish varieties became extinct, it was clear that the classical forms were the most durable: the Quaver, the Wotsit, the Ringo; timeless shapes that exist outside fickle underage fashion. The only long-stay snack to have joined their ranks since the golden years is Golden Wonder’s Nik-Nak, which made a virtue of its own deep-fried deformity, a scampi ‘n’ lemon flavoured Elephant Man. So popular has it become around the world in various guises, it’s even earned the highest accolade of all: its very own dedicated extrusion cooker. So if you fancy making your own unlimited supply of Nik-Naks, get your hands on the JRJ Nik-Naks Extruder, a snip at £37,000. You might have to supply your own cheese slurry, though.