1 JACK D. WARREN JR. on George Washington

“Our national independence is Washington’s legacy.”

BOOK DISCUSSED:

The Presidency of George Washington (U. of Virginia Press, 2002)

We don’t lack for George Washington scholars. The United States has an abundance of them, and their books have together given a relatively full rendering of the Revolution’s indispensable man—the man of whom it was said at his funeral that he “was first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Like many Americans, as a youth I was taken by my parents to Mount Vernon. That began my own lifelong admiration for our first president, the only Founding Father to free his slaves at his death.

When I took my own son, then about eight years old, to visit Mount Vernon, he saw a large twig on the ground and asked if that was a part of the cherry tree that Washington had cut down as a young boy. Although the cherry-tree story is a myth, I could not destroy the illusion for an eight-year-old. I replied that I could not tell a lie and that it indeed had been a part of the cherry tree.

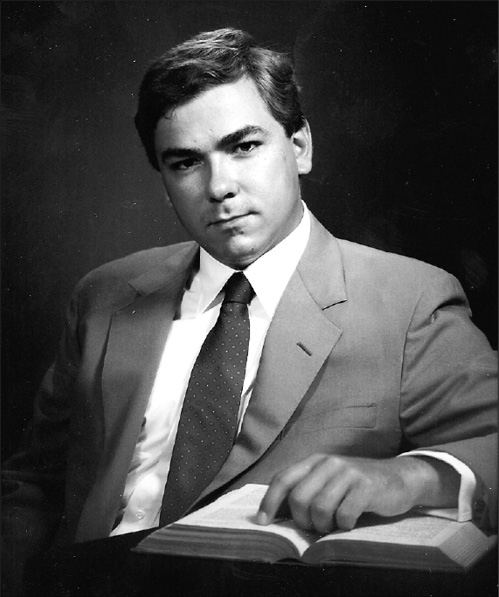

I asked Jack Warren to do the interview on George Washington because Jack has an encyclopedic knowledge of our first president, having devoted much of his adult life to studying him. His book on Washington’s conduct as president is an excellent look at how Washington essentially invented the office and established traditions and practices still in use more than two hundred years later.

Jack has devoted his career to promoting the memory of Washington and the American Revolution. For a good number of years, Jack served as an editor for The Washington Papers, a project still ongoing under the auspices of the University of Virginia. He fought successfully to save the site of Washington’s childhood home. Today, Jack leads the American Revolution Institute, a public nonprofit created to ensure that all Americans understand and appreciate the achievements of the American Revolution. He is also the executive director of the Society of the Cincinnati. (The modern members of the society are descendants of Washington’s officers.)

Although there were no Rubensteins who served as officers in the Revolutionary War, a few years ago I was made an honorary member of the Delaware chapter of the society. Through the society, and through events at its headquarters (Anderson House in Washington, D.C.), I have interviewed Jack more than a few times. His affection and respect for Washington and his knowledge of Washington’s life are unmatched, as is apparent in the interview.

In our conversation, Jack Warren makes clear why George Washington was easily the first among equals of the Founding Fathers. On three occasions, he left the tranquility and comfort of Mount Vernon to help his fellow citizens, fulfilling a role that no one else in the colonies (and later the country) could have done as well, if at all.

First, he led the American troops in battle against the seemingly invincible British. (Few Americans had Washington’s military experience.) Second, he presided over the Constitutional Convention, an assemblage unlikely to have even occurred, much less succeeded, without his presence. Third, as the first U.S. president, he ensured the new American government would work, and set the precedents that have helped guide his forty-four successors so far.

As Jack recounts, Washington was able to achieve these three feats not because of an engaging, back-slapping, hail-fellow-well-met personality. Standoffish, if not regal, in bearing and demeanor, he was more than a bit distant from his colleagues and even his fellow Founding Fathers. He led not through a dynamic, engaging personality but through example. He set a high bar for himself and met or exceeded it. Others saw this and followed his lead.

But Washington’s greatest legacy was his willingness to give up power. Generals who led military victories typically became rulers for life if they could. Washington returned to Mount Vernon at the end of the Revolutionary War, content to resume the life of a gentleman farmer and plantation owner. He could readily have had a third term and presumably served as president until his death, but he chose the opposite course. He retired to his home and gave up all his government power.

Back at Mount Vernon, Washington lived only two and a half more years. He could have lived longer had he been less hospitable: after riding several hours through a rainstorm, he arrived home drenched and cold, but refused to change clothes and keep his dinner guests waiting. The result was a swollen epiglottis, difficulty in breathing, and a failed effort to address the problem by bloodletting (i.e., cutting veins to let the “bad blood” out of the body). That shortly produced shock, and ultimately death. Jack relates the unfortunate outcome in the interview.

Interestingly, Jack notes, Washington had two uncommon provisions in his will. First, he arranged for his slaves to be emancipated after his death (the only Founding Father to do so). Second, he asked not to be buried for two days. In those days, doctors left something to be desired, and they sometimes authorized patients to be put in coffins before death had actually occurred. Washington was, in fact, dead before being placed in his coffin.