MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): Of all the Founding Fathers, the one who still commands the most admiration and respect is probably George Washington. Why is that?

MR. JACK D. WARREN JR. (JW): George Washington led the Revolution for our independence. Without him, our revolution would have failed. Our national independence is Washington’s legacy. We are sitting in this city in the greatest country in the history of the world, in the greatest republic since the fall of the Roman Republic, as a consequence of Washington’s actions.

DR: George Washington grew up in what’s now called Mount Vernon—named, ironically, after a British admiral. Washington’s older half brother was an officer in the British navy, is that right?

JW: Washington moved around as a child, but when he was a teenager, he spent a lot of time at Mount Vernon, which was the home of his half brother Lawrence Washington. Lawrence was an officer in the Virginia colonial militia and served as a volunteer officer under Admiral Edward Vernon in an attack on Cartagena in a brief naval war between Britain and Spain, oddly named the War of Jenkins’ Ear.

DR: So his brother named Mount Vernon.

JW: He did. He had admired Admiral Vernon. George Washington later inherited Mount Vernon, but he never changed the name, and so lived in a house named for a hero of the British Empire.

DR: George Washington wanted to be an officer in the British military at one point?

JW: Lawrence thought George might become an officer in the Royal Navy, but there is no evidence George ever warmed to the idea. When he was in his twenties, George Washington wanted to secure an appointment as an officer in the regular British army.

DR: And he was rejected?

JW: He played an important role as a Virginia militia officer in the French and Indian War and came to the notice of regular British army officers—including men he would later fight during the Revolutionary War. He realized then that the British army offered no real opportunities for a colonial and that his ambition was never going to be realized.

DR: Washington does do some fighting in the French and Indian War of 1754 to 1763 and gets a reputation. Then he’s elected to the Continental Congress—the governing assembly in Philadelphia, made up of delegates from the thirteen colonies—and serves as leader of the American forces during the Revolution. Why did they pick George Washington, who wasn’t that famous a military tactician or general? Why did the Continental Congress say, “We want you to lead the troops in the American Revolutionary War”?

JW: He was the best man available. He was a Virginian. The Revolution had begun in Massachusetts, and most of the early fighting was in New England. Congress realized it needed somebody from outside New England to lead the army. Although George Washington had never led more than a couple of hundred men, he was the most experienced military leader in Virginia, the largest of the colonies. Moreover, Washington had the bearing of a soldier. He stood out.

DR: Because he was six foot two?

JW: Yes, but much more than that. Because he commanded respect. In the weeks after the fighting at Lexington and Concord, Congress debated how to respond. George Washington said very little in those debates. He was never much of a public speaker. But he appeared each day in his Virginia regimental uniform, as if to say, “A war for the liberty of America has begun. We must fight, and I am prepared to do it.”

DR: People say that when they asked him, “Why don’t you be the leader of our troops in the Revolutionary War?” he said, “No, I don’t want to do it.” Finally he said okay, and it turned out he had already brought all of his uniforms up from Mount Vernon. Is that true?

JW: He was modest, which is one of the things people admired about him. In accepting the command, he said, “I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.”

But if I could be a fly on the wall, one of the scenes I would like to see is Washington packing his military uniform for the trip to Philadelphia. Surely Martha knew he was taking his uniform, and what this might mean.

After he had accepted command of the Continental Army, he wrote a letter to her, one of the only letters he wrote to her that survives. “You may believe me, my dear Patsy,” he began, “when I assure you, in the most solemn manner, that so far from seeking this appointment, I have used every endeavor in my power to avoid it, not only from my unwillingness to part with you and the family, but from a consciousness of its being a trust too great for my capacity.… But as it has been a kind of destiny, that has thrown me upon this service, I shall hope that my undertaking of it, is designed to answer some good purpose.”

It’s a charming letter, but the idea that he had tried to avoid the appointment is not true. He wanted it. He just didn’t imagine that the war would last for eight years, and that in those eight years he would see Mount Vernon only once, for a single night, when he was on his way to Yorktown.

DR: How old was he when he became the general of the American forces in the Revolutionary War?

JW: He was just forty-three.

DR: The same age as John Kennedy was elected president.

JW: We are used to thinking of Washington as a mature man—a man in his late fifties or sixties, as he was when the most familiar portraits were painted. But in 1775 he was a robust young man in the prime of his life. He was a great horseman, a fine dancer, and a gifted athlete.

DR: He was robust and athletic, but he had not been educated, right? No college, no high school, no grade school.

After leading American troops to victory in the Revolution, George Washington served as president of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 that oversaw the creation of the U.S. Constitution, establishing a federal system for the newly independent country.

JW: Washington had had as much education as a typical planter in his station. His formal education ended when he was about fourteen. Our thinking about his education is skewed, because some of the other leaders of the Revolution benefited from a fine formal education. Thomas Jefferson graduated from the College of William and Mary, James Madison from Princeton, and Alexander Hamilton from Columbia.

But some of the greatest minds of that century, and certainly the greatest Americans of that generation, were more simply educated. Franklin had little formal education. Patrick Henry was the most eloquent American of the eighteenth century, if not of all time, and he had no more formal education than Washington.

DR: So Washington took the job and said, “I’ll do it, but I don’t want to be paid. Just cover my expenses.” Is that what almost broke the Continental Congress? Because his expenses were pretty significant.

JW: Washington’s expenses were significant. Some revisionist historians try to poke holes in Washington’s reputation by pointing out that this was really a good deal. But keep in mind that Washington’s expenses as commander in chief included all the expenses of his military staff. He also had to pay the costs of espionage. There was no NSA, CIA, or military intelligence apparatus, and no congressional appropriation for intelligence. Washington managed much of that himself, and the costs show up in his expense accounts.

DR: That’s a fair point. How many troops did he actually command in the Revolutionary War? Was it more than twenty thousand at any point?

JW: At its peak, when the army was gathered around New York City in the summer of 1776, Washington had about thirty-five thousand men to defend America from the greatest military expedition any European power had ever sent overseas. Those thirty-five thousand included the Continental Army—the regular army upon which Washington relied—and short-term militia.

DR: And many of those men were not well armed or well equipped. At Valley Forge, for example, one-third had no shoes. Was he always fighting with Congress to get them paid? How did he actually hold them together?

JW: Washington was continuously struggling to keep the army together. The army was always underpaid. It was always underfed. It was always poorly shod. It was always short of arms.

When the war began, we didn’t have a single factory for making muskets or a gunpowder mill capable of supplying an army. We didn’t have bronze for making cannon barrels or sufficient lead for musket balls. We had no workshops to produce tents, uniforms, knapsacks, and all the other things consumed in war. We never had enough money. Congress issued paper money unsupported by gold or silver, and it soon became worthless.

Washington appealed continuously for support from Congress and from the states. He appealed to the patriotism of his men. He shared their suffering. He held the army together through the force of personality. People believed in Washington. The men who fought with him believed that he would lead them to victory.

DR: He camped in Valley Forge during the winter. Why was it that when winter arrived, the troops just stopped fighting? In other words, the British said, “We’re not going to fight in the winter.” And the Americans didn’t fight then either. Why did they not think they could fight in the winter? It was too cold?

JW: Fighting slowed dramatically in winter, but it rarely stopped. Washington kept patrols on the roads around the British army to prevent them from collecting supplies from American farms. Skirmishing went on all the time.

The British were in an unusual situation, conducting a war of conquest thousands of miles from Britain. They were able to take American cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah, but they were never able to establish control of the interior. They were never able to live off the land. They had to depend on supplies brought from overseas. Moving supplies overland in winter was simply too arduous, so the British went into winter quarters and waited for spring. Every year the British hoped that this would be the year they would bring Washington to bay.

DR: In November 1776 there was a battle at Fort Washington, on the island of Manhattan, and almost three thousand American troops were captured. As general, Washington himself you could say was responsible for that. We lost several thousand men. There was a movement afoot to replace him as the general of the American army. Did that get very far? Did Congress lose confidence in him?

JW: This was the darkest moment in the war. The British attacked New York in the summer of 1776 with some thirty-six thousand men, including German mercenaries, and a fleet of warships. Their goal was to take the city, crush Washington’s army, and end the rebellion in one swift campaign. Congress expected Washington to defend the city, but the task was nearly impossible. New York is an island city, surrounded by a maze of navigable waterways that favor an attacker who enjoys naval superiority. The British could move their army at will. They took the city without much difficulty, and they beat Washington’s army in a series of battles.

Fort Washington, which is at the north end of Manhattan, was the last American stronghold on the island. Washington’s officers assured him they could hold it against a British attack for months. When the British attacked, the fort fell in a matter of hours. The German mercenaries, the Hessians, led the attack, and when they took the fort, they began slaughtering American prisoners. Washington watched through a spyglass from the other side of the Hudson. He knew that he had made a tragic mistake, and he quietly wept as he watched. Washington retreated with what was left of the army, fewer than six thousand men, across New Jersey, hoping to get across the Delaware into Pennsylvania. Congress fled Philadelphia, expecting the British to take that city as well. It looked at that moment like the war was coming to an end.

DR: Did he not write, “I think this is the end. We’re not going to make it”?

JW: The crisis led Washington to draw on his innermost strength. He refused to accept defeat. He worked to keep what was left of his army intact, and he assured his men that they could still prevail. He told them to hold firm and that victory could be achieved.

Thomas Paine, who was with the army, caught that spirit of defiant determination, and wrote a pamphlet called The Crisis that Washington had read to the army. “I call not upon a few,” it said, “but upon all: not on this state or that state, but on every state: up and help us; lay your shoulders to the wheel; better have too much force than too little, when so great an object is at stake. Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.”

Washington understood that the British needed to win the war quickly. The longer it went on, the more likely the French, Britain’s historic foe, would join the war on America’s side. Washington was determined to hang on. His battered army believed in him and followed him back across the icy Delaware to victories at Trenton and Princeton—victories that shocked the British and inspired Americans to keep fighting. This was his greatest moment.

DR: Eventually we won the war at Yorktown. On October 19, 1781, the British general Lord Cornwallis surrendered to the American forces, led by Washington, and their French allies led by General Rochambeau. The war dragged on for another eighteen months, but the British finally accepted American independence and signed a treaty of peace in 1783. At that moment, Washington resigned his commission and went home to Mount Vernon. When he heard this, King George III said, “If George Washington gives up power, as I hear he’s going to, he’s the greatest man in the world.” Why did he say that?

JW: Because it had never happened before and has scarcely happened since. Whether we’re talking about revolutions we like or revolutions we don’t, revolutions of the far right or the far left, they have a defining feature. The men who led them hold on to power. They convince themselves that they are the revolution. And they behave as Cuba’s Fidel Castro behaved, and hold on to power as long as they can. And more often than not, they become ruthless tyrants.

Washington believed the revolution he had led was our revolution. When it was over, he surrendered the authority he had been given and entrusted the fate of the nation to its people. He knew that it was a critical moment. He wrote a letter to the states, which was immediately published all over the country, in which he asked Americans to dedicate themselves to the high ideals of the Revolution. “It is yet to be decided,” he wrote, “whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse: a blessing or a curse, not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn millions be involved.”

DR: So, for example, Cromwell, Napoleon, Mao, Lenin, Castro—when they led revolutions, they stayed in power. The fact that Washington went back to Mount Vernon was unusual. When he went back to Mount Vernon, what did he do? He just went back to being a planter?

JW: He did, although it was difficult for him. Washington enjoyed farming, at least as an intellectual exercise. He enjoyed experimenting with new crops and improving his plantation. But he was, even in retirement, the most important figure in the country. People came to see him and wrote to him about public affairs almost continuously. He knew almost everyone in public life and was universally respected. Mount Vernon, he quietly grumbled, was “like a well-resorted tavern,” always filled with visitors, and they invariably wanted to talk with Washington about political issues.

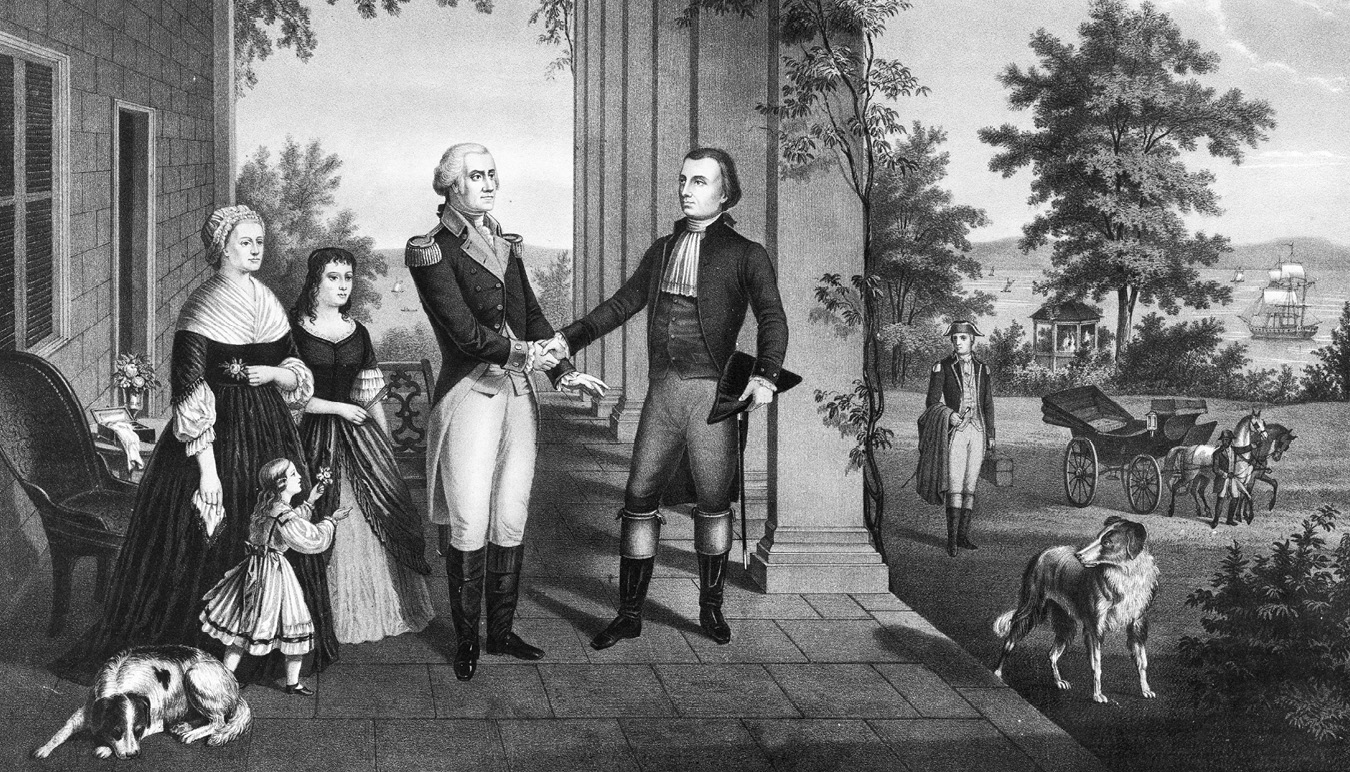

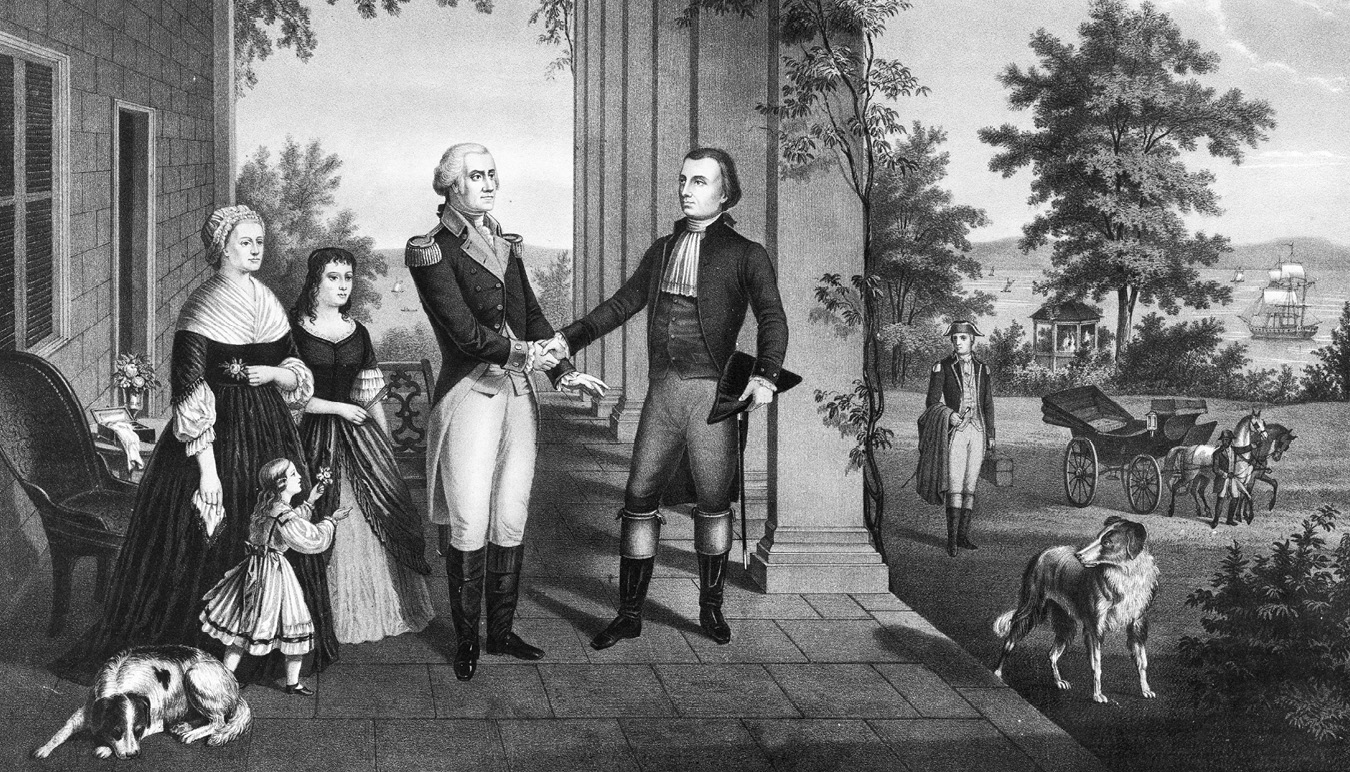

Washington’s roles of general and gentleman farmer combine in this mid-1800s image showing the general and his family at Mount Vernon in 1784, bidding farewell to General Lafayette, Washington’s staunch French ally.

DR: The country was then being governed under the Articles of Confederation, which brought the original thirteen states together in a loose confederation that gave little power to the federal government. James Madison says it’s probably not working. He goes to George Washington and says, “Would you be willing to chair a convention to figure out how to amend the Articles of Confederation so as not to completely get rid of them?” Why did George Washington agree to do that?

JW: Madison persuaded him by reminding Washington of what mattered most to him. He predicted that the republic would fail, and Washington’s legacy would be forgotten, if Washington refused to act.

Washington—like Benjamin Franklin and some of the other leaders of that generation—had conceived a vast ambition. He wanted to be remembered, like the heroes of classical antiquity that he’d been taught to admire since boyhood, as the founder of a great republic. He wanted us to have this conversation about him this evening. That was his private ambition. He wanted us to remember him.

Madison warned him that the republic would crumble if Washington did not lead the effort to reform the Articles of Confederation. Washington didn’t want to be remembered as the virtuous founder of a failed republic. He was willing to risk his reputation by coming out of retirement to save the republic he had spent so many anxious days and sleepless nights to establish.

DR: The Declaration of Independence was adopted in Independence Hall in Philadelphia. In 1787, the Constitutional Convention is convened in the same place, Independence Hall, and George Washington is elected the head of it. The entire time the new Constitution is being debated, he doesn’t say one word, except at the very end. Why was that?

JW: Washington was one of the most skilled politicians of all time and lived by the general principle that what it’s not necessary to say, it’s necessary not to say. He knew that he didn’t have to say much in the convention. James Madison had arrived with a plan for a new constitution, and the men who could be counted on to support discarding the Articles of Confederation and adopt a new and more effective form of government included some of the most gifted minds of the early modern world.

Washington also understood that one of the main tasks of the convention would be to provide for an effective federal executive. Nearly everyone present agreed that the convention should propose a single executive with considerable authority. There was only one person anyone could imagine entrusting with that authority, and he was sitting quietly in the front of the room. Washington was destined to lead the new government, and he made sure that it was a government designed by others, so that no one would suggest he had fashioned its powers for himself.

DR: When the convention concluded and the Federal Constitution was submitted to the states for ratification, Washington didn’t get involved. He didn’t urge anybody to ratify the document. Why?

JW: He had, in fact, endorsed the Constitution by signing it. He had associated his own prestige with the Constitution, and no argument offered in favor of it was as powerful as Washington’s endorsement. He fully expected the document would be ratified, and that he would be called upon to lead the new government. He saw no reason to spend his political capital in debate. He didn’t believe he needed to, and events proved him right.

DR: So the Constitution was ratified, and George Washington was elected president by the unanimous vote of the electors. Did he really want to be president of the United States, or was he forced into it? Would he have been happy just to stay at Mount Vernon?

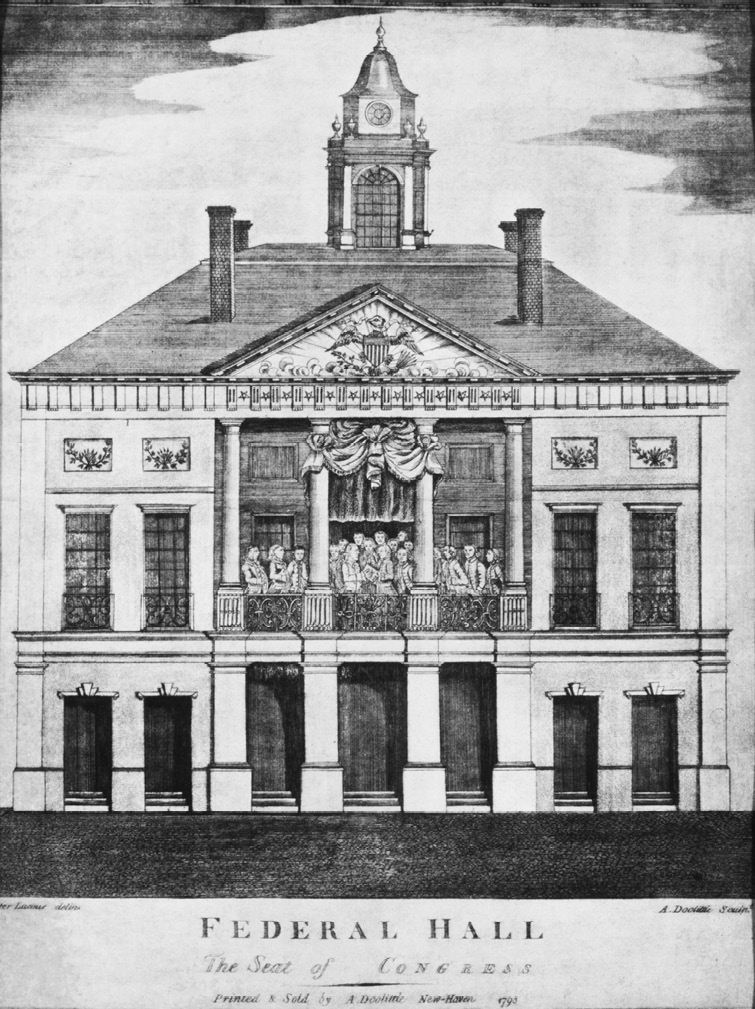

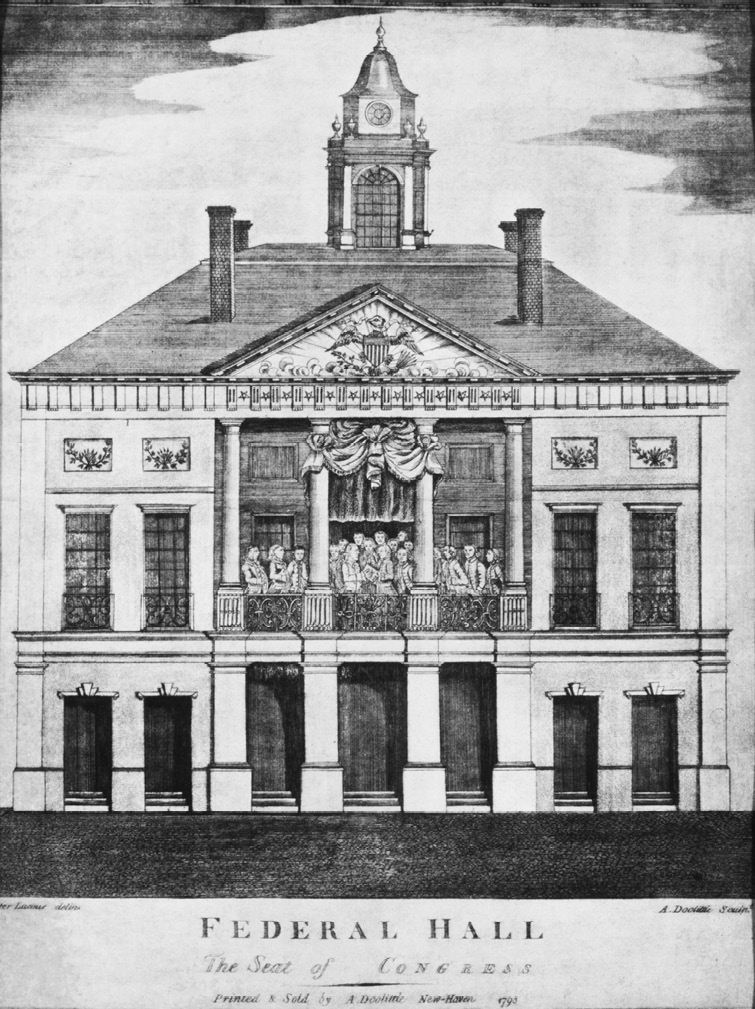

Reluctantly elected as the nation’s first president, Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City, then the seat of the U.S. government.

JW: Washington wrote and said repeatedly that he didn’t want to be president. And when politicians say that kind of thing—

DR: Remember who you’re talking to here.

JW: When politicians say, “You know, I don’t want to be elected, don’t do this”—we don’t believe them. But Washington meant it. He wrote to Henry Knox, his intimate friend, in a private letter, that “my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares, to quit a peaceful abode for an Ocean of difficulties.… Integrity & firmness is all I can promise.”

DR: He was elected unanimously. And under the Constitution, whoever got the most votes from the electors was president and whoever got the second most was vice president. So the vice president was John Adams. At the beginning of their administration, Washington thought he would involve Adams in governing, but he got mad at him. He never talked to him for eight years. Is that right?

JW: At the outset, Washington didn’t know Adams very well, and neither man had a very clear idea what the vice president ought to do. In the early weeks of the administration, Washington called on Adams for advice, and if things had happened differently, the vice presidency might have emerged as a much more important role.

But early in the Washington administration, Adams pressed the Senate to adopt a title for the president similar to those associated with kings. A committee finally suggested “His Highness, the President of the United States, and the Protector of Their Liberties,” which Adams endorsed. This proposal did not go over well in Washington’s own Virginia, where critics continued to warn that the new government would deprive the people of their liberties. Thereafter Washington kept his distance from Adams. He treated Adams cordially but gave him no responsibilities, which led Adams to call the vice presidency “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

DR: George Washington wanted to be called “Your Excellency”?

JW: Washington actually shared Adams’s concern about establishing public respect for the presidency and the new government in general. “Your Excellency” was a common way of addressing a state governor, and not consistent with the dignity of the presidency Washington worked to establish. James Madison proposed “Mr. President,” which has endured.

Washington understood, better than others, that respect for the presidency would ultimately have little to do with titles and other formalities. He knew that public regard for the office would depend upon the conduct of the men who held it. He recognized that the eyes of the world were on him, and he worked constantly to promote the public interest, discourage partisanship, and avoid the slightest appearance of using his office for his private benefit or the benefit of friends or relatives.

In this regard, as in many others, he was a revolutionary, though we don’t always recognize it. Consider the familiar Gilbert Stuart portrait of Washington, in which Washington wears a simple black suit. Today that kind of suit—or some variant—is the daily attire of most heads of state. But in 1789, when the world was ruled by kings and emperors wearing crowns and purple robes edged with ermine, Washington’s dress was a revolutionary political statement. Washington’s revolution is now so complete that we no longer see how revolutionary it was.

DR: The new government met first in New York and then moved to Philadelphia, but quickly passed the Residence Act, saying that we’re going to have an entirely new capital and that the man in charge of figuring out where it’s going to be is the president of the United States. And the president of the United States decides he wants to build it somewhere on the Potomac River. How did he decide? Did he come down and actually look at the sites himself? Did he have other things he had to worry about, or did he have time to go find a site?

JW: The Residence Act called for the establishment of the federal seat on the Potomac River, somewhere between the mouth of the Anacostia River and a stream called Conococheague Creek, which is up in Washington County, Maryland, near Hagerstown. Washington had lived on the Potomac River all of his life, and he knew exactly where he wanted to put this city, but he didn’t want to appear impulsive or biased in any way, so he rode up the river and visited all the potential sites. In fact, he’d already made up his mind, and the tour was political theater. He had chosen the area between the mouth of the Anacostia and Rock Creek. He believed that this could become the site of the greatest city on earth.

DR: And the city was built by slave labor?

JW: Slave labor was involved in the construction of most buildings and other improvements in Washington through the Civil War. The site of the federal city was a mix of undeveloped woods interspersed with small farms. In the early years there was never enough labor to clear the land, construct the unpaved streets, and build the essential buildings. The managers had to hire slaves from local plantation owners.

DR: It was hard to get the money, so Washington came up with a lottery system to try to raise money. In the end, it almost didn’t happen. How close did it come to not actually getting built?

JW: Very close. The Residence Act of 1790 was the mother of all unfunded mandates. Congress authorized Washington to choose the site for a federal city but neglected to appropriate any funds to acquire the land or build the public buildings.

DR: That would not happen now.

JW: No. Nothing like that happens anymore.

Actually, the whole business was as politically charged as anything in our history. Congressmen from Pennsylvania didn’t want to see the government leave Philadelphia, and congressmen from other northern states hoped the city would never be built and that the government would remain in Philadelphia or return to New York. So they refused to appropriate money for the project. They didn’t understand Washington’s determination. The president came down to Georgetown, which was then a little port town, and met with all the local landowners.

I picture this scene—forgive me, this is a little bit irreverent—like one of those late-night infomercials about buying real estate with no money down. In effect, Washington said, “Look, here’s the plan. All of you are going to deed over the rural land you own to a neutral trustee. And the neutral trustee is going to divide it up into building lots and city streets. And you’re going to get back two-thirds of the land that you gave us in city lots. That means you are going to give away a third of your land to us, some of which is going to be used for city streets, and some as lots for public buildings. The government won’t pay you for your land, but your city lots will be worth a lot more than your rural real estate. The federal government is going to sell off most of its lots and with the proceeds we will pave all the streets, which is going raise the value of your real estate. What do you say?”

And, of course, this is George Washington making the pitch, and everybody signs on. With that the city was born, despite the fact that Congress didn’t appropriate any money.

Washington watches every detail of the development of the city. He’s determined to see it rise. He thinks that it can be a combination of contemporary London and Paris. It can imitate the glories of ancient Rome and Athens. He thinks it can be the greatest city on earth.

DR: Did he say, “Let’s name it Washington”?

JW: No. George Washington was far too modest for that. He referred to it for the longest time as the Great Columbian Federal City. Considering the fact that it was undeveloped woods and farmland, this was a bit of real estate development hyperbole.

DR: Where did the idea of naming the city after Washington come from?

JW: The idea of naming the city after George Washington was tossed around in the press and in private correspondence from the time the Residence Act was passed. Washingtonople and Washingtonopolis were both suggested. So was Columbia. Congress decided to name the entire one-hundred-square-mile federal enclave the District of Columbia and authorized the president to appoint commissioners to oversee the construction of the city inside the district. The commissioners voted to name the city Washington.

DR: In his lifetime it was called Washington?

JW: Yes, in his lifetime.

DR: As president of the United States, George Washington only had three people in the cabinet?

JW: Four, if you include the attorney general. Congress authorized the departments of state, treasury, and war, with secretaries to run each department. The attorney general—Edmund Randolph—didn’t have much public business to do and was admitted in the courts of Pennsylvania.

DR: Washington’s secretary of state was Thomas Jefferson, and his secretary of the treasury was Alexander Hamilton. And they didn’t get along too well?

JW: They were two of the most brilliant men of their time, but they had little in common. Jefferson was a Virginia planter and well connected socially. Hamilton—some ten years younger—was a West Indian immigrant who had pulled himself up from obscurity. Jefferson had spent the Revolutionary War as a legislator, governor, and diplomat. Hamilton had been a soldier—an artillery officer and then aide-de-camp to Washington. They were barely acquainted before they met in Washington’s cabinet and they almost immediately developed a dislike for one another.

DR: Hamilton was in favor of a stronger federal government and Jefferson was in favor of a weaker federal government. Is that a fair characterization?

JW: I see it a little differently. Both men wanted to ensure the survival of the republic and wanted the federal government to be a success.

Jefferson was in Europe, serving as our ambassador to France, when the Federal Constitution was framed and ratified, and he was a rather remote spectator to the process. He supported revision of the Articles of Confederation, but his friend James Madison had to convince him of the wisdom of adopting the new Federal Constitution. When he arrived home to take up his duties as secretary of state, he was in favor of a small federal government empowered to conduct the diplomatic affairs of the new nation and provide for the common defense, but otherwise limited in scope.

The problem with Jefferson’s vision is that it did not provide for dealing with the crippling debts left over from the Revolutionary War. Brilliant as he was—and this great Library of Congress is a monument to the energy and scope of his imagination—Jefferson was obtuse about economics. He never understood banking and finance and was deeply concerned that Hamilton’s solutions for the nation’s debt crisis would destroy the republic by placing inordinate power in the hands of financiers.

Hamilton’s experience as a soldier had convinced him that only a robust federal government could protect the republic from impotence and insolvency. Hamilton was in favor of a solvent federal government.

When Washington became president of the United States—you all may laugh at this—the United States was about $85 million in debt. I realize the national debt of the United States has increased $85 million while David and I have been talking. But $85 million was an enormous amount of money in 1789. It was so much money that few Americans imagined that the United States could get out of debt within fifty years even if all of the revenue that the government could expect to raise through customs duties, the chief source of federal revenue, was dedicated exclusively to retiring the debt without doing anything else.

Hamilton created a plan to save the United States from indebtedness by creating a reliable system for funding the debt. This stabilized the value of federal securities and increased market liquidity by making it possible for debt instruments to circulate like money. This in turn encouraged investment and entrepreneurship and helped to release the creative energy of the American economy. Jefferson never understood any of this. He saw it as a system that would fasten debt and taxes on the American people and deprive them of personal independence.

DR: Did Jefferson anonymously write articles or have them written criticizing Hamilton while he was secretary of state?

JW: Yes, and Washington knew it very well. I marvel when people say we live in a time of unprecedented political partisanship. In the Washington administration, the secretary of state put a man on the public payroll, ostensibly as a translator, whose actual role was to edit a newspaper critical of the Washington administration.

DR: Of which Jefferson was the secretary of state.

JW: Right.

DR: Ultimately Jefferson resigned, went back to Monticello, and said some things that are not so favorable about the intellect of George Washington. And I gather Washington never talked to him again. Is that true?

JW: Jefferson returned to Philadelphia in 1797 when he was elected vice president. They went in together to the hall where Adams and Jefferson would take their respective oaths of office—a fascinating scene, because Washington arrived at the door first but then stepped aside so Adams could walk through, leaving Washington and Jefferson in the doorway. Jefferson waved his hand, deferring to Washington, but Washington shook his head, insisting that the new vice president precede him. They shook hands, exchanged pleasantries, and never spoke again as long as they lived.

DR: All right. So Jefferson’s back in Monticello. Washington doesn’t really want to run for a second term, but people come to him and say, “You’re the only person, run again,” and he decides to run again. Is that correct?

JW: Washington had been reluctant to serve as president. He wanted to get out of the presidency as quickly as possible. In 1792, at the end of his first term, he sat down to write a farewell address. It’s not as eloquent as the one Hamilton helped him write later. It actually has a little Nixonian ring to it, a kind of “You’re not going to have George Washington to kick around anymore” tone. He was our first president, and he was the first person to get a real taste of what being president was like. Washington never got used to being criticized in the press, and by 1792 he was ready to retire.

His advisors, including Jefferson and Hamilton, talked him out of it. The last thing that I think Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton ever agreed on was that Washington had to accept a second term or the Union would fragment. Washington relented. He accepted a second term and came to regret it.

DR: At the end of that second term, when he leaves, he writes what’s called a farewell address that Hamilton helped write. But it wasn’t an address. He didn’t deliver it to anybody. He sent it out as a letter and left for Mount Vernon and just went home.

JW: He didn’t intend to give it as a speech. He issued it to the newspapers, explaining that he would not accept another term as president of the United States, and offering some parting advice. He left us to manage our own affairs. Hamilton helped Washington write it, but the sentiments are very much Washington’s own. And like our greatest state papers, it still has much to teach us.

DR: So he just went home to Mount Vernon and said, “You go elect somebody else”?

JW: He remained in Philadelphia through the election and inauguration of his successor, and then he packed up and went home. We are now so used to this ritual transfer of power that we no longer see how truly revolutionary it once was. In a world ruled by kings, there were no former heads of state.

DR: When he gets back to Mount Vernon, he becomes a country squire again. But at one point, when Adams was president and we were afraid that France might invade the United States, Adams went to Washington and said, “Would you lead the army again?”

Washington’s example, and his exploits, continue to resonate in American culture. This 1940s pie advertisement invokes the general’s famous crossing of the Delaware River.

JW: Washington agreed to command a provisional army organized to defend the nation in the event of invasion. He makes a couple of trips to Philadelphia to confer about the business and entrusted the organization of the army to Alexander Hamilton, who was made second in command at Washington’s request. Washington didn’t expect a French invasion, but he was willing to lend his prestige to the administration to calm public fears, which were soon dispelled.

DR: So Washington was back at Mount Vernon, and then one day it begins to sleet while he’s out riding around his estate. He comes back completely wet. He has guests for dinner. (I think I read that he and his wife had not had dinner alone together for twenty years because they always had guests.) Rather than go up and change out of those wet clothes—he didn’t want to be impolite and hold his guests up any longer—he sits down and has dinner with them. And then what happens?

JW: He had been out riding in sleet and rain for several hours, and by night he was very sick. Whether he would have avoided it by changing out of his wet clothes and warming up, we’ll never know. For a long time, historians thought he had developed pneumonia, but the current view is that he contracted epiglottitis, an infection of the cartilage covering the windpipe—something that can be cured very quickly with antibiotics today. When it is badly infected and swells, the epiglottis blocks the flow of air into the lungs. Every breath is agonizing, and the sufferer gradually suffocates.

DR: Three doctors came. They looked at him and said, “The treatment that you need is to get rid of your blood. You have too much blood.” So they let one quart of his blood out of his system.

JW: In their defense, therapeutic bleeding was a common early modern treatment, particularly for fevers. Washington was a big believer in therapeutic bleeding. He’d actually instructed one of his farm managers to come and bleed him before the doctors arrived. So it was his idea. The bleeding undoubtedly weakened him, but it probably didn’t cause his death.

DR: He was sixty-seven when he died. He said, “Do not bury me for two days.” What is the reason for that?

JW: There had been a great deal of literature in the latter part of the eighteenth century about people being buried prematurely—often people who were in shock, which is a medical condition doctors were only beginning to understand. Washington had read some of this literature and was worried about that.

DR: After he died, there was a debate about whether he should be buried up at the Capitol or at Mount Vernon. Where is he buried?

JW: Washington had directed that his body should be placed in a simple tomb at Mount Vernon. Many public officials thought that Washington should be entombed in the Capitol, and Mrs. Washington, with considerable reluctance, agreed, but it took many years for the proposed crypt beneath the Rotunda to be finished. When it was finished, the new owner of Mount Vernon refused to allow Washington’s remains to be disturbed. The crypt in the Capitol is empty, and we have been spared a spectacle like Lenin’s Tomb. I think Washington would be pleased.

DR: Now, in his will, he did something that no other Founding Father, I believe—certainly none from Virginia—did, which is he freed his slaves. He had about 130 or so slaves, but he actually directed that they should be free upon the death of his wife. If you were Martha Washington and you were told that the slaves will be free as soon as you’re dead, is that a good thing for you to know? How did they resolve that?

JW: With great difficulty. George Washington had been born into a world in which slavery, as abhorrent as it is to us, was a part of everyday life. He benefited all of his life from the labor of people he deliberately enslaved. But during the Revolution and the years that followed, he came to the conclusion that slavery was both inefficient and unjust, and made plans to free his slaves.

The situation was complicated. Half of the roughly three hundred slaves at Mount Vernon in 1799 were so-called dower slaves. They, or their mothers or grandmothers, had once belonged to Martha Washington’s first husband, and George Washington did not own them. He benefited from their labor, but they were the legal property of the Custis heirs and would eventually go to Martha Washington’s grandchildren. George Washington could not free them. His own slaves had intermarried and mixed with the dower slaves, and freeing his own slaves while leaving the dower slaves in bondage would break up families.

The law, moreover, discouraged freeing slaves. Legislators were reluctant to facilitate the growth of the free black population, into which runaways might disappear. The market for the labor of freed slaves was limited. And while legislators rarely considered the interests of enslaved people, they discouraged slave owners from evading their responsibility to care, in a minimal way, for elderly, infirm, or chronically ill slaves by making it hard to free them. In anticipation of freeing them at his death, Washington worked to ensure that many of his slaves learned crafts that would provide them with marketable skills, and he provided funds to care for the elderly and infirm for the rest of their lives.

When the terms of Washington’s will became public, Washington’s slaves learned that they would be free when Mrs. Washington died. She decided not to wait and freed them herself.

Washington included a provision in his will to emancipate the enslaved people he owned. In this portrait of George and Martha with her grandchildren, the unidentified man in the background may be William Lee, an enslaved African American who served with the general during the Revolution.

DR: Washington’s most famous eulogy was given by Henry Lee, who said that George Washington was “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” As a scholar, you have spent your entire life studying George Washington. Do you admire him more now, or do you see his flaws and admire him less than when you started your studies?

JW: It has been the greatest privilege of my life to spend it in the study of this person. He’s the only historical character I’ve studied who rises in my estimation every year that I study him. Washington was an extraordinary person.

He had flaws and he made plenty of mistakes. But he learned from his mistakes, and rarely made the same one twice. He was an immensely prudent person. He was a man of great character. He was also an idealist—even a visionary. We don’t usually think of him that way, but we should. Here we are, in a city he imagined, in a nation he devoted his life to creating, living under a form of government he did more than anyone else to vindicate—a government dedicated not to the interests of kings and aristocrats, but to the interests of ordinary people. Nothing like it had ever been seen in the world.

There is another characteristic of George Washington I particularly admire. He thought in the long term. His correspondence is laced with the phrase “a century hence.” He thought about what our country would be like in a hundred or even two hundred years. And he did so in the crush of everyday political life, in which decisions had to be every day made under the pressure of events, in a hectic world like our own. He thought about us. He thought about the twenty-first century. He challenges us to think about a distant posterity—about the world we are making for generations yet unborn.