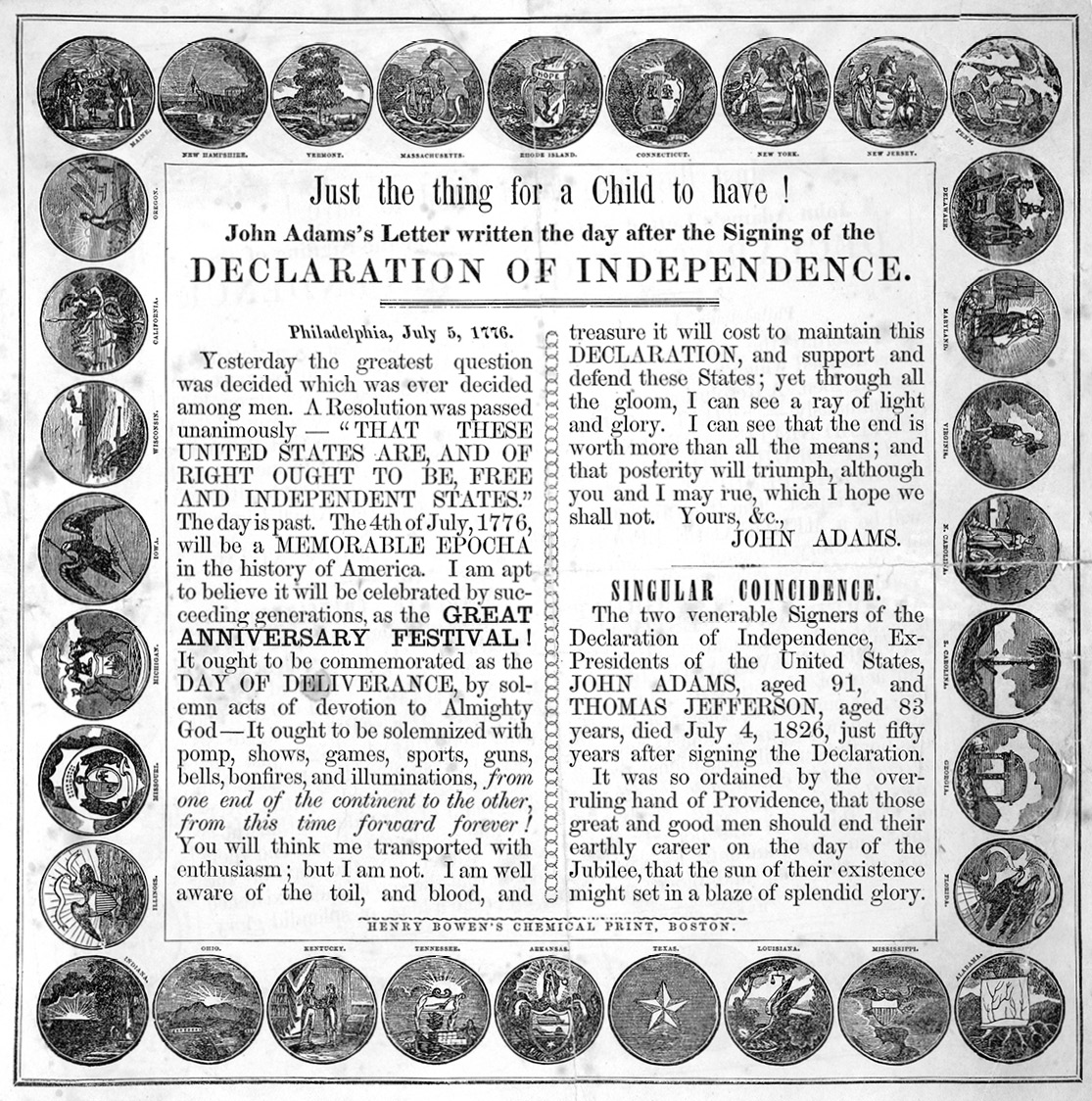

“Just the thing for a Child to have!” Commemorative 1850s broadside of Adams’s passionate letter, July 5, 1776, about the importance of the Declaration of Independence.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): David, thank you very much for doing this. Before we start, how many people here would rather hear David McCullough than be at the White House for the state dinner? Raise your hands. Okay.

So, David, you have written several books that have won Pulitzer Prizes, and we’re going to talk about one of them tonight. I would like to start by asking you this question. After your book came out, people were amazed that John Adams had this incredible life, and said, “How can it be the case that we have a monument to George Washington, we have a monument to Thomas Jefferson, but for the second president of the United States there’s no monument in Washington?”

Ten years after your book came out, there’s still no monument. So here are the people who can do something about that. Why should there be a monument to John Adams?

MR. DAVID McCULLOUGH (DM): In 2001, Congress voted to provide a place for a John Adams memorial within the District of Columbia, and it was signed by President George W. Bush, so that all the legal aspects of the idea have been covered. The real problem is to organize enough support for it, because John Adams doesn’t have a constituency, say, the way American nurses or teachers do.

And it’s a shame. He’s the only one that isn’t represented. I would be all for it, but I wouldn’t want it to be tucked off someplace where it was not part of the experience of people coming to see our capital and to appreciate it.

I love what he said about this subject in my notebook here, and it was a tribute he wrote to the capital, his benediction. Some of you may know it. It’s a simply marvelous message that I hope will be remembered for generations: “Here may the youth of this extensive country forever look up without disappointment, not only to the monuments and memorials of the dead, but to the examples of the living.”

Adams was a great optimist, and I think that’s part of why he’s so American. We are by nature optimists, and we know that the hard times and troubles and periods where nothing seems to be happening very effectively come and go. And that we can do it if we work together.

America is a joint effort in everything. If you read history, you know that nothing of any real consequence, or very rarely, has ever been accomplished alone. And he knew that.

I think he’s one of the most remarkable human beings in our story as a nation. I also think his wife, Abigail Adams, was one of the greatest of Americans. They led extraordinary lives. Theirs is an amazing story.

There’s an old adage about writing novels: keep your hero in trouble. Both John Adams and Harry Truman were constantly in trouble, so I didn’t have to worry about that.

DR: Now, when you started to write your book on John Adams, you were actually going to write a different book. You were going to write a book about Revolutionary heroes, including Jefferson. Why did you decide to just write a book on Adams?

DM: I had the idea of doing a dual biography. It was going to be Jefferson and Adams. I thought that having both onstage, as it were, I could see them in a different way from how they have been seen before, or even how they were seen in their own time.

I was a little worried how I could keep the glamorous, famous, handsome Thomas Jefferson from upstaging this short, cranky Yankee. Once I got into reading what Adams wrote—the way he poured out his heart and soul in his letters and diaries—I realized what a human being he was.

History is human. That’s what it’s about—“When in the course of human events…” History is about people, and it’s the people of history that we need to know and understand. Why they did what they did, why they were the way they were. What were they up against, what were their advantages, and so forth? Who were their friends? To whom were they married? All of that.

Jefferson tells you nothing about his wife. We don’t even know what she looked like. He called in every letter that she may have written to friends of theirs and destroyed them. Destroyed every letter that he wrote to her and she wrote to him. How can you portray this man very effectively? He built a wall around his personal life. He didn’t want people intruding on that. And you go where the material is.

If I may just sidestep a little bit, I was giving a talk at a university in California, and during the question-and-answer period one of the questions was, “Aside from Harry Truman and John Adams, how many other presidents have you interviewed?” And I said, “Appearances notwithstanding, I did not know President Truman or President Adams.”

But if you get to read their letters, if you’re surrounding yourself with what they said privately, publicly, what they said to someone they love, what they said to their children, what they said to themselves in their diaries, you get to know them, in many ways, better than you know people in real life. In real life you don’t get to read other people’s mail.

The unfortunate thing about all of us is that none of us write letters anymore, and no one in public life dares to keep a diary anymore. It can be subpoenaed against you in court. And here were these people pouring their selves out on paper because of the old sense of working your thoughts out on paper.

Adams writes about this. He says, “It’s only when I sit down at the desk with a piece of paper and my pen that I can really start to think.” And again and again in his diary you’ll read, “At home thinking.” Imagine. Taking time to think! And what a mind. What an incredible brain.

So I thought, “No, I’m going to write about Adams. And that’s more than enough, right there. That’s one of the greatest American lives I know about.”

DR: Maybe we can convince people that there should be a great memorial. Let’s go through his life a bit. John Adams was from a not wealthy family but a family that had been around Massachusetts for a while. His father was a farmer and a preacher. John Adams went to Harvard and then became a lawyer. He was well respected, and ultimately he was elected to the First Continental Congress. When he got there, it turned out that he was more articulate and a stronger believer in independence than other people. How did he become such a leader from the beginning?

DM: I’d like to recast what you said a little bit. John Adams came from very humble origins. His mother was illiterate. They had maybe one book in the house, which was the Bible. And they had no money.

The father did something he’d never done, to help pay for him to go to Harvard. He sold some land. The father was a farmer, as you say. And John went to Harvard on a scholarship, and when he got there, he said, “I discovered books and I read forever.”

You have to keep in mind this is not the Harvard that we know today. This is a small school with a small faculty, six or seven professors, several hundred students. And he did get a law degree. He taught school for a while. And he stood for practicing what you preach.

One of the bravest and most important acts of his life took place when no one would defend the British soldiers after the Boston Massacre. No one would dare do that because it would have been so infinitely unpopular. He said, “Well, if we believe in what we say, somebody’s got to represent them. If you all won’t, I will”—knowing in his heart at least that it would probably destroy any ambitions he had for a leadership life in Boston or Massachusetts or national politics.

But instead, it made him more popular. Because they saw what backbone this man had. That he wasn’t just doing this to follow the crowd. He was doing what he felt was right. And he did that again and again and again in offices he held right up to and including the presidency.

DR: After he defended the British soldiers who took part in the Boston Massacre, he was elected to the legislature in Massachusetts, and then they sent him to the First Continental Congress. And there he became a leader from the beginning?

DM: Yes. Because he was a man who was willing to get into the arena. He would stand up on the floor of the Congress and battle articulately, and never with personal invective, for what he stood for. He’s the one that really put the Declaration of Independence over, on the floor of the Congress. If he’d only done that, he would be someone of infinite importance in the story of our country.

Remember, everybody that signed that document was signing his death warrant. All the odds were against us. Only about a third of the country was for independence. A third of the country was against it. And the remaining third, in the good old human way, was waiting to see how it came out. We had no military strength, we had no money, we had very little in the way of military experience, and we were up against the most powerful nation in the world, with the most powerful navy, most powerful army, and we thought we could do it.

The other thing people don’t realize, or unfortunately don’t know enough about, particularly students, is that the Revolutionary War wasn’t a quick little thing. It was eight and a half years. It was the longest war in our history except for Vietnam. And very bloody, proportionate to the size of the population.

DR: In addition to being the most ardent advocate for independence, Adams made two decisions. He recommended somebody to be the general of the army for the American colonies and somebody to write the Declaration of Independence. Why did he pick George Washington and why did he pick Thomas Jefferson?

DM: He picked Jefferson because he felt he was the best writer. And he liked him very much and admired him very much.

Washington was a clear choice. There wasn’t really much mystery about that. There were so very few to choose from, and they were all young, in their thirties or early forties, with no experience. They’d never done this before; none of them had. And it’s just miraculous, out of this tiny population—2,500,000 people, and 500,000 of them were slaves held in bondage. Couldn’t vote, had no say.

One of the most important virtues or admirable qualities that we all should know and understand about John Adams is he’s the only Founding Father to become president who never owned a slave. As a matter of principle. And Abigail was staunchly of that same point of view. The slaves weren’t all in the South. They were sort of a status symbol in Boston, and you had servants who were slaves. That was the thing to have.

DR: He was not an abolitionist, though?

DM: No, he wasn’t. Nobody was making an issue of that at the time because they had determined that “we can’t solve this one now—we’ve got to sidestep that.” They were really putting in the closet an issue they knew eventually had to be solved.

DR: The Continental Congress vote to separate from England takes place on July 2, 1776. John Adams then writes to Abigail, “This will be the most important day in the history of our country, July the 2nd.” Why do we celebrate Independence Day on July 4 instead of July 2?

DM: This is something that he wrote on July 2, 1776. That was the day they voted. Your wonderful Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol has the painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull, and almost everything about it is wrong.

Nothing happened on July 4. That’s the date on the document. And all those people weren’t assembled to sign it. They signed it when they were in town, as it were. Some of them signed in the fall, some were signing all the way up to Christmas. And the furniture in the painting is wrong. The room, the decorations of the room are wrong.

The only thing that’s right, and it’s what’s most important, are the faces. They were all representative of individual Americans—free, independent Americans—who are stating their political faith and who are accountable. In other words, they can’t hide anymore. There they are. Proudly, but not without courage to do that.

Adams wrote that day or the next day: “The 2nd day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding generations, as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as a day of deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”

“Just the thing for a Child to have!” Commemorative 1850s broadside of Adams’s passionate letter, July 5, 1776, about the importance of the Declaration of Independence.

Think about it for a minute. He’s saying, “From one end of the continent to the other.” The country at that point didn’t even reach the Allegheny Mountains. And he’s seeing this dream, this ambition. Like John F. Kennedy saying, “We will go to the moon.” This is an American moment, and it is more than just legally interesting or legally important, profound, and unprecedented, which it was. And Adams had that capacity.

Adams was short, and he was not very handsome, and he comes right after the presidency of the tallest, most glamorous, important figure in the world then, George Washington, and before the glamorous Thomas Jefferson. And to me, it’s very interesting that it’s the same situation with Harry Truman. He comes after Franklin Roosevelt and is succeeded by Dwight Eisenhower, two of the most luminous figures of that day. But you have to wait for the dust to settle, and you begin to see who really did matter.

Right here, across the way here, over at the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, there’s a piece of sculpture commemorating the goddess of history, Clio. She’s riding in her chariot, and there’s a clock on the side of the chariot, and she’s writing in her book.

The idea behind putting the statue there was that the members of Congress would look up to see what time it is. That clock still keeps perfect time. That’s a Simon Willard clock, made in Massachusetts about 1850. They would look up to see what time it is, and they would be reminded that there was another time—history—and that what you’re saying today, what you’re doing today, here on the floor of this legislative assembly, is going to be judged in time to come, in the long run.

There’s present-day time and then there’s the time of history. And the best and most effective people in public life, without exception, have been the people who had a profound and very often lifelong interest in history. You have to understand history in order to understand who we were, how we got to where we are, why we are the way we are, and where we might be going. And that you are going to be judged by history, not just by tomorrow morning’s headlines. And they were worried about this back at the very beginning.

DR: Was Adams upset that later on we didn’t celebrate July 2, we celebrated July 4? And why do we celebrate the Fourth?

DM: Because that’s the date that’s on the document. “When, in the course of human events…” July 4, 1776. But no, he didn’t mind.

So often in history, what really happens, you couldn’t put it in a novel. Nobody would believe it. The truth is stranger and more wondrous, very often, than fiction.

The idea that Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the two men who put the Declaration of Independence over and changed history, changed the world, then died fifty years later on the same day, July 4, 1826—unbelievable. And yet it really happened.

They came to Adams right before he died. It was about two or three days before. The newspaper reporters came to him and they said, “Mr. Adams”—he was sitting up in a chair that’s still there in the Adams house in Quincy, Massachusetts—“we’re going to be celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Do you have anything to say?”

He said, “Yes. Independence forever.”

“Would you like to say a little more, Mr. Adams?”

“Not a word.”

DR: After the Declaration of Independence is signed, the Revolutionary War goes forward; Adams is asked to go to France and see if he can get the French in as allies to help America in the Revolutionary War. How did he get to France? He couldn’t fly over, so describe the boat ride and how he went and whom he took with him.

DM: He went over by sailing ship, which was the only way you could go anywhere. And he took his little boy with him, John Quincy Adams. So you had two future presidents riding in the same ship.

It was dangerous just to go to sea in those days, but very dangerous to be going to sea when the sea happened to be controlled by the British navy. And if they were captured, he would be taken and hanged.

And he didn’t speak a word of French. He began scurrying around and buying all the books he could get on France and managed to teach himself French pretty effectively on the voyage over. It was a very difficult voyage, and he did it several more times before he was finished. Going, coming back, and going back to Europe a second time. He was a very brave man.

It was a very courageous time. You have to understand what they were reading at the time. For example, they had no rules of punctuation. Never used quotation marks—nobody did. When you’re reading their letters, you’ll come across a wonderful line or two. You think, “Oh, isn’t that great?” And then you find out that, no, they’re quoting a line from some poet or Shakespeare. It happens all the time.

They all did it, because they knew that the person they were writing to knew the line. It would be as if in a letter you would say, “Well, I guess we’ll just have to follow the Yellow Brick Road.” You probably wouldn’t put quotation marks around that.

One of the lines that appears again and again in the Founding Fathers’ writings is a line from Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”: “Act well your part, there all the honor lies.” In other words, history has cast you in these roles and you better damn well play that role to the best of your ability. And why? “There all the honor lies.”

Nobody talks about honor anymore. Not money, not fame, not power—honor. And they really believed that. Of course, they didn’t always live up to it, but they believed it.

So there’s a certain creed, a certain faith that we need to know more about, because it was the fuel of their courage and their persistence in the cause of equality and freedom and the freedom to use our minds to think for ourselves. This great institution [the Library of Congress] was signed into existence by John Adams, a man who never stopped reading.

When he was in his eighties, he embarked on a sixteen-volume history of France in French, which he taught himself. And he told his son, little John Quincy—one of my favorite of all lines—“You’ll never be alone with a poet in your pocket.” Take a book, carry a book. Don’t go anywhere without a book. And he would urge poetry.

There’s so much about this man that needs greater appreciation, but I feel immensely gratified that my book has reached such an audience as it has. The book is now in its forty-eighth edition.

Nothing can please me more than that the story of that amazing American is out there for people to know him and be enlarged by him. Adams et al. set such an example, and that’s why it’s so imperative that we teach history—the example of those who preceded us.

DR: When Adams finally gets over to France, he finds out he’s got two colleagues he’s got to negotiate alongside: Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. They’re in France as well. What was it like for the three of them representing the United States? Was it easy for the three of them to get along?

DM: Well, I say this not to put Jefferson down, but Jefferson didn’t arrive until the war was over. So all the tough stuff was over. He came in when it was easy. Franklin was there before Adams.

Jefferson was not one to get in the arena. He would not get up on the floor of the Continental Congress and say what he really thought. He wasn’t that kind of man. That’s in keeping with when he goes to France. It was all safe. The war was over.

Adams gets there and discovers that Franklin is loved by everybody. Anything the French want, he’s all for it. His way of dealing with them was to just be as nice as he could and try to be as much like them as they were and enjoy some of the privileges of life that weren’t always approved of at home.

And he was not well, so he couldn’t get around very well. He really didn’t swing into action until about eleven-thirty in the morning.

DR: He seemed to have a lot of girlfriends. He was very popular?

DM: He was very popular with the people out in the street. I hate to use this analogy, but it really was a good cop / bad cop situation. Franklin was the one the French all loved; Adams was the one who kept saying, “You gotta do something. We could lose this war any day now.”

Keep in mind—this is so important to understand—how different that time was. We think of transportation and communication as two different things. In that day they were the same. You couldn’t communicate anything across the ocean any faster than it would take you to go across the ocean on a boat.

So when a diplomat arrived in a foreign country, the decisions that that person made, the actions that he took or things that he said, were his decisions. He wasn’t getting orders from back home. If he did get orders from back home, they might be two, three months late getting there. The war could have been over back here, and John Adams and Benjamin Franklin might not have known until three or four weeks or more after it had ended.

The responsibility they felt—it’s the same thing with women at the time. When Abigail had to decide whether to inoculate their children for smallpox, knowing that the very process of the inoculation could cause the death of one of her children, she couldn’t call up John down in Philadelphia and get advice over the phone or tell him: “You get on the next plane and come back here. I want you to be here for this decision.” She had to make that decision herself. And right or wrong, it would always be her decision.

We spread responsibility. We divide it up. They had to make decisions themselves, on their own, and right or wrong, it was their responsibility.

DR: The Americans win the war, and Adams is appointed to be our ambassador to, of all countries, England. What was it like for him to go over to England and meet King George III, who was the terrible hated figure? How did that work out?

DM: It worked out quite well. They really admired each other. George III was a much more interesting and appealing man than I ever understood before. Yes, he made very unfortunate decisions. And yes, he could be stubborn in the extreme. But he was interesting and not without feeling. He had a good heart.

Once they got over the stagy difficulties of the first presentation, when they first met each other in the ceremony where the new ambassador goes to present himself, both of them were so emotionally moved by that moment they couldn’t speak. A very powerful scene.

I must say that the rendition of it by Paul Giamatti in the HBO miniseries John Adams was superb. The whole series was superb. That’s the finest rendition, the most accurate portrayal of life in the eighteenth century that’s ever been on the screen.

It’s really due to the integrity of executive producer Tom Hanks. When we first met to talk about it, I said, “I don’t want it to be a costume pageant. I want you to show what life was like—dirt under the fingernails, bad teeth, suffering, smallpox.” When the British representative was tarred and feathered—tar and feathering was cruel punishment, it was torture, it wasn’t some adolescent prank—that’s all in that film, which is sometimes very hard to watch.

And the other thing I said was: “Don’t violate the vocabulary. Keep it in the language of the time. Let’s hear that beautiful use of the English language.” And because both Paul and Laura Linney, who played Abigail Adams, were trained as classical actors, they could handle those lines. To my knowledge, there was never any complaint from viewers that they couldn’t understand what the characters were saying.

DR: When Adams is finished as ambassador and comes back to the United States, we have a new Constitution. After spending a little time on the side writing the Massachusetts state constitution by himself, he’s elected vice president. Was it a foregone conclusion he would be vice president? And how did he get along with President George Washington?

DM: He was elected vice president by popular vote, and he took his job very seriously in that he officiated over the Senate every day. I’m sure there were days he wasn’t there, but very few. Probably no one who’s ever had the job was more conscientious about showing up for work.

And you think the Congress has its difficulties today? They went at each other one day on the floor of the Congress with fire tongs. It was rough and tough, lots of contention. Washington stayed away from it. He didn’t want anything to do with Congress. He wanted to play the role of the chief executive, and he played it superbly.

One of the greatest, luckiest breaks in our whole history as a nation is that George Washington was our first president, because he set the example of integrity, strength of purpose, and devotion to the country. Patriotism—not just the flag-waving kind, but real love of country. Keep in mind too that he was our chief executive, he was our commander in chief, for sixteen years, because we had no president during the war, and he was the commander.

As you know, when George III heard that he was going to retire and not take power after winning the war, the king said, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man on earth.” And, again, there was the example. And Washington retired in 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was signed ending the war. He was elected president in 1789, after the U.S. Constitution was ratified. He really did nothing wrong or embarrassing or corrupt or self-serving as president.

DR: But Adams thought that the title “Mr. President” wasn’t appropriate. The president should be called something better?

DM: Yes.

DR: There was a little fight over that, and George Washington and Adams for eight years barely talked. Is that true?

DM: No. Not true.

DR: How much did they talk?

DM: They didn’t talk the way we do today. Well, yes, maybe they did. Not too much talking seems to be going on today.

No, I think it had more to do with the interpretation they each had of the role they were playing. But there was no animosity between them. It was difficult sometimes. They were two very different human beings. But Adams hugely admired Washington, and so did Abigail. Abigail just thought he was “it.” And he was “it.”

DR: When Washington says, “After eight years, I’m going to retire,” was it a foregone conclusion that Adams would become president?

DM: Yes. But of course he had to get elected. And he would have been reelected.

This is something that isn’t taught, and we don’t know it—he kept us out of a war with France. And he knew that if he did that, it would probably cost him reelection.

He did it because he had common sense. We were up against this very powerful nation. In that day, if you went to war with France, you were going to war with Napoleon, and you didn’t mess with that guy. We had no money, we had no army, we had no navy to speak of.

Adams and John Marshall, who became chief justice, figured out, “We can get out of this and we don’t have to go to war”—and they didn’t, and thank heaven they didn’t. Adams said, “If I have anything on my gravestone that I should be remembered for, it’s ‘I kept us out of an unnecessary war.’ ” And it was true, and of course he did lose the election of 1800.

DR: He lost to his own vice president, Thomas Jefferson?

DM: Yes, he did. And he lost in a very major way because of what he did.

I wanted to tell you a little story about Adams. His son died of alcoholism and his mother died, all right around the change of the new year into 1801. He’d lost the election. He had every reason in the world to be the bluest, most depressed creature imaginable—and he was, to a very large degree.

One night in the White House, before he had to leave—with newly elected Jefferson coming in—he looked out and saw that the Treasury was on fire. There was snow on the ground. He immediately jumped up—the president of the United States—grabbed his coat and hat, ran across the lawn over to the Treasury building to help the bucket brigade put out the fire. And they succeeded. The next day there was an article in the paper saying that citizens all gathered and got the bucket brigade going and, inspired by the example of their leader, put the fire out.

Now, the question is, why did he do that? He didn’t have to do that. He was the president. There’d be other people doing that. It was instinctive. You’re a good citizen; you pitch in. Very New England, very rural, very understanding of how we make civilization work.

When Adams lived in Washington, D.C., as president, much of the nation’s new capital was still semirural.

DR: If you had the chance to have dinner with John Adams, what would you want to ask him?

DM: I’d want to ask him: “What can we do to increase the love of learning? What can we do to bring back the attitude toward reading and books and knowledge and thinking that was such a part of the adrenaline of your time?”

I’d like to read you a clause in the Constitution of Massachusetts, which John Adams wrote. Wrote the whole thing. It’s a clause that was never in any constitution up till then and is still not in any other constitution except New Hampshire’s. I think it’s a reminder to all of us of what our obligations are, not just to these oncoming generations, but to our country and its future.

He says, “Wisdom and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people, being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties; and as these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education in the various parts of the country, and among the different orders of people”—in other words, everybody—“it shall be the duty of legislatures and magistrates, in all future periods of this Commonwealth, to cherish”—wonderful word—“cherish the interests of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them in public schools and grammar schools in the towns; to encourage private societies and public institutions, rewards and immunities, for the promotion of agriculture, arts, sciences, commerce, trades, manufacturers, and the natural history of the country; to countenance and inculcate the principles of humanity and general benevolence, public and private charity, industry and frugality, honesty and punctuality in their dealings; sincerity, good humor, and all social affections, and generous sentiments among the people.”

How about that?

DR: If you had a choice to have dinner with John Adams or Harry Truman, who would you have dinner with?

DM: John Adams, because I want to know more about that very distant and different time.

I didn’t know Harry Truman. I saw him once. But I really understood a lot about Harry Truman. I would love to have talked to Harry Truman. There’s so much about him that people of the time didn’t know. People of the time didn’t know that Truman sat at home at night and read Latin for pleasure. This was the failed haberdasher. He knew nothing.

Truman had many qualities that are similar to John Adams. They both had great courage. Backbone. They were willing to say what they felt. They knew how to make decisions.

And they also understood that they were a link in a long chain, that the sun didn’t rise and set on them; they weren’t the greatest thing that ever happened in the history of the country, and they better act well their part and play their part. “There all the honor lies.”

Harry Truman made some very difficult, very unpopular decisions, but he knew they were right, best for the country in the long run. They were willing to lose in order to do what was right. And to hell with what the public ratings and tomorrow’s headlines could say.