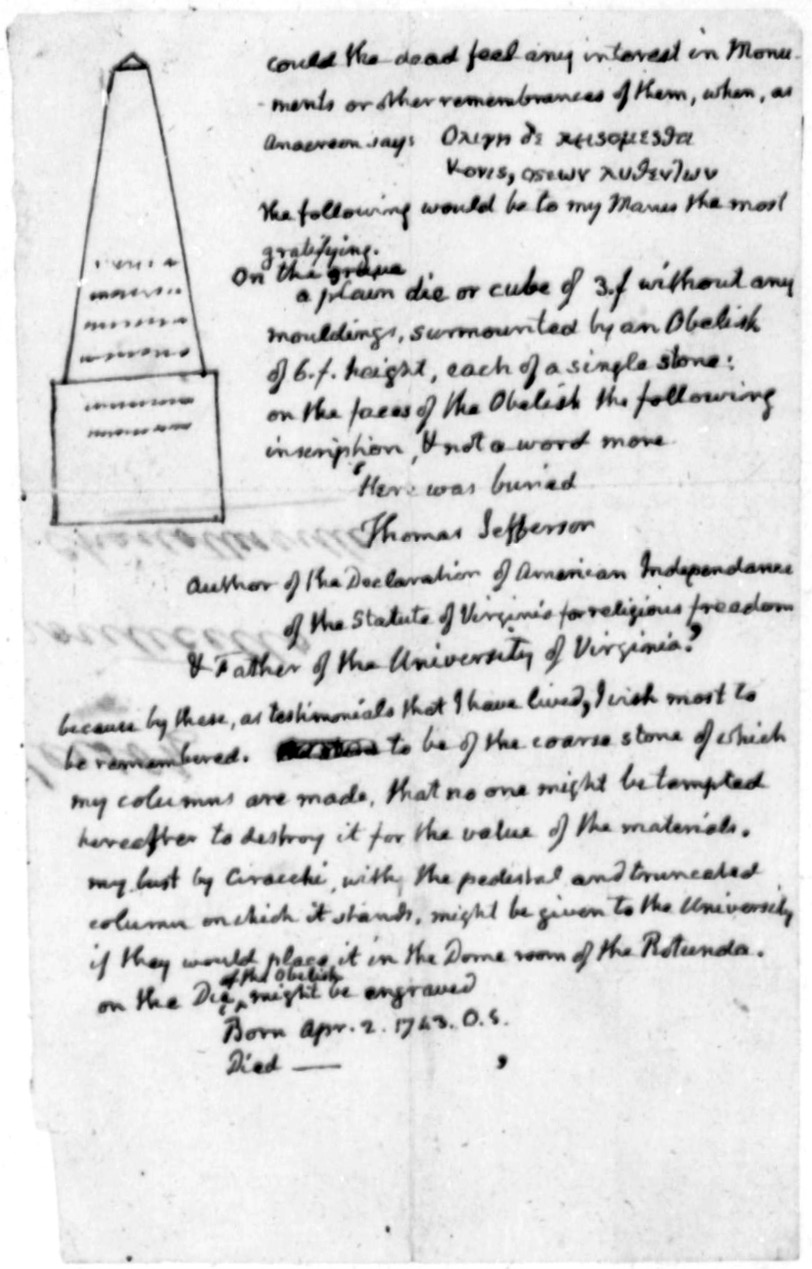

Jefferson sketched out his own epitaph and grave marker, probably in March 1826, not long before he died.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): Many people in this city, and people around the country, would say the highest calling in political life is being president of the United States. Maybe you would say being vice president isn’t too bad or being secretary of state isn’t too bad. Yet when Thomas Jefferson was asked what he would like to have on his tombstone, he didn’t say president of the United States, secretary of state, or vice president. He said, “Author of the Declaration of American Independence, Author of the Virginia Statute for religious freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia.” Was he not happy with his tenure as president of the United States? Why did he not put his government positions on his tombstone?

Jefferson sketched out his own epitaph and grave marker, probably in March 1826, not long before he died.

MR. JON MEACHAM (JM): I think the epitaph that he designed—he drew the tombstone, and we still have that document—is one of the great acts of misdirection in American history. As Freud will tell you, often what you do not say is as important as what you say. I think Jefferson realized that his political career would be forever controversial, because political careers by their very nature are controversial. When you are elected, if you’re doing really well, you get 55 or 60 percent of the vote, and that’s not all that common. On your best day, 40 to 50 percent or more of the people you see are against you. I often wonder how presidents get up in the morning realizing that almost every other person they see doesn’t want them to be doing what they’re doing.

Jefferson disliked controversy, yet he was irresistibly drawn to it. That’s one of the contradictions of his life. He loved politics, he loved the arena, but he believed that being seen as the author of the document about human equality, about liberty of conscience and enlightened education, would be an achievement about which there would be less debate going forward than whether the embargo should have gone in in 1808 or what he did during his vice presidency or as secretary of state. [The Embargo Act of 1807, which took effect in 1808, embargoed British and French trade during the Napoleonic Wars, with serious negative consequences for the U.S. economy.]

DR: You’ve now spent five years of your life studying Thomas Jefferson. You’ve spent almost every waking hour learning about him, reading everything about him, and you’ve produced a best-selling book. After five years of studying him, do you admire him more than you did before, or do you see so many flaws that you say, “This is not the man I thought he was”?

JM: I admire him more because I see more flaws. Let me explain that.

You can tell I’m a southerner and a Christian, so I believe in forgiveness. I do what I do in part because for a long time I was a working journalist—for twenty years—and I started looking back at Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, Andrew Jackson and Jefferson, in part to see whether the world seemed as complicated and confounding and difficult in their time as our world does now. And the answer is yes, for in real time we never know how the American story is going to turn out. We now know how the founding of the United States turned out, we now know how the Civil War turned out, we know how the civil rights movement turned out, we know what happened at Normandy on D-Day in World War II and beyond, but they didn’t.

The reason I find biography so compelling is that when you look at great American figures, whether it’s Jefferson or, Lord knows, Jackson—Andrew Jackson’s life was sort of a combination of Advise & Consent meets Bonanza; you didn’t want to cross him because he would shoot you—Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy, when you look at the great figures, their vices are almost as large as their virtues.

To me, the whole world turns on the word almost. To me, it’s remarkably inspirational that flawed, sinful human beings were able to, at moments of great crisis, transcend those limitations and leave the country a little better off than it was before. And Thomas Jefferson did that. For all his contradictions, for all his derelictions, which I’m sure we’ll talk about, the country was a better place, the world was a better place on the Fourth of July 1826, when he died, than it had been in April of 1743 when he was born.

DR: On July 4, 1826, Thomas Jefferson was eighty-three years old. It was fifty years to the day after the Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress in 1776. What happened on that day in 1826 elsewhere?

JM: Well, in Massachusetts, John Adams once again got his headline stepped on by Thomas Jefferson. Poor Adams could never get one clean news cycle. He died on the same day. One of the last things he said was, “Jefferson lives.” He was wrong in that particular moment, because Jefferson had died earlier in the day, but Adams was right on the bigger point, because Jefferson does live. He does continue to resonate. Of the early founders, he is the one who resonates the most for us.

I’d be bold enough to say I think that might be particularly true for members of Congress, because he did what you do. From 1769 until 1809, he was almost constantly holding or seeking public office. He left George Washington’s cabinet in order to do that. As John Adams put it, it’s remarkable how political plants tend to grow in the shade.

I believe that on that day in 1826, Jefferson, revered as the author of the best of the American promise in the Declaration of Independence, knew that his epitaph would stir up a deep interest. He also knew, I think we know now, and people in his own time knew, that very few people had failed so clearly in their own personal lives to realize that promise. No one ever said it better and no one ever really fell so short, and I think in that tragic distance lies an extraordinary American life.

DR: The Declaration of Independence contains a sentence that Jefferson wrote—with some editing we’ll talk about—and that some people would say is the most famous sentence in the English language. I think you all know it by heart: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” How could a man write that all men are created equal when he had two slaves with him in Philadelphia, owned sixty slaves at the time, and owned six hundred slaves during his lifetime, and there’s no evidence that he freed very many slaves when he died? How could he have said all men are created equal?

JM: He meant all white men at the time. The contradiction you point out is that tragic failing to see how the promise he articulated could apply to those other than his own kind.

Remember what was going on when he wrote that sentence. It’s a civilizational shift. This is not just American exceptionalism, it’s really remarkable. The political tradition of which you are the heirs, the operative heirs, was the clearest Western manifestation of the greatest shift in a thousand years or more.

What had happened in the century or so before the American Revolution? The Protestant Reformation, the translation of sacred Scripture into the vernacular, the European Enlightenment, the Scottish moral enlightenment, John Locke and the idea of self-government. The world was going from being vertical to being horizontal. It was vertical for a long time—with the divine right of kings, your entire destiny was shaped by the station to which you were born, and you had no other alternative. Everything came from above.

What did Jefferson do? He gave political manifestation to this shift from a hierarchy to a democratic—lowercase d—ethos, in which suddenly human rights, or the rights of all men being created equal, came from the Creator. What did that mean? If they came from the Creator, that meant neither the hand of the king nor the hands of a mob could take them away. It was an incredibly important intellectual and political shift.

DR: As a young man, Jefferson said some things that were not favorable about slavery, but he realized he wasn’t going to get anywhere in Virginia politics if he was in favor of abolition. Was his view really that we had to tolerate slavery? What was his solution to that problem?

JM: In a very un-Jeffersonian way, he had no solution. The slavery issue is one of our central original sins. The other is the forced removal of Native Americans.

The Constitution codified our compromises on slavery. Everyone here knows that. Thomas Jefferson would not have been president of the United States—the Virginian presidential dynasty of Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe would not have been possible—without the Three-Fifths Compromise. [At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, delegates agreed that three-fifths of each state’s enslaved population would count toward that state’s total population, an important number for determining how many representatives each state would get in Congress. The compromise increased the political power of the southern states.]

The purchase of Louisiana in 1803 led to the first great secessionist movement in the country, which was not in the American South but in New England, because New England saw the country moving south and west and slave states being added that would dilute the power of New England. When I was working on the book and I was thinking about the psychology of that moment, I was reminded of when my wife and I had two children, a boy and a girl, and my wife became pregnant and we found out it was going to be a girl. My son came to me and said, “Daddy, we’re going to be outnumbered, and I don’t like our chances.”

That’s what Timothy Pickering was doing in Massachusetts. He was going to be outnumbered, and it wasn’t going to work out very well, and in fact it didn’t, because the political power of New England was diluted. [Pickering, a Massachusetts politician who served as secretary of state and in the U.S. Congress, opposed the Louisiana Purchase because he worried that New England would lose its influence if the country expanded westward.]

The reality of slavery in that era was that there were some plans for emancipation, there was some talk about expatriation [i.e., sending African Americans to Africa], but William Lloyd Garrison [the famous abolitionist crusader] was not a force in the early part of the nineteenth century. If Thomas Jefferson had fallen off a horse in 1783, he would have been a source of great tags of rhetorical flourishes for the abolitionists, because on four or five occasions as a young man—as a trial lawyer, a young legislator—he did try to take steps to reform the institution of slavery, and he lost each time.

We’re here in a room of political folks. What do political folks dislike a great deal? Losing.

So when, in the Confederation Congress in 1783–84, he had written a provision that would have banned the expansion of slavery to the west, he lost by a single vote. [The Confederation Congress ran the new country from 1781 to 1789.] A delegate from New Jersey hadn’t shown up, and Jefferson later wrote, “In that moment the voice of heaven itself was silent and the fate of millions still unborn hung in the balance.”

It’s a wonderful phrase. No president ever spoke in needlepoint-pillow terms better than Thomas Jefferson. It’s a goose-bump kind of line, but it was, in fact, simply rhetoric. At that point, he realized his political power would be diluted in direct proportion to his opposition to slavery.

He also could not imagine his own life without it. One of the first things we know about Jefferson, his first memory, is of his being handed up on a pillow to a slave on horseback to be taken on a family journey in Virginia.

One of the last things we know that happened in that summer of 1826 is that he’s lying in that alcove bed in his home at Monticello, which I’m sure many of you have seen, and he’s uncomfortable, and he’s trying to signal to his family what’s wrong, his white family, and no one gets it except an enslaved butler who reaches over and fixes the pillow and all is well again. His life was suffused and made possible and supported by slavery, and he simply could not make the imaginative leap to emancipation.

The final thing I’ll say on this is that we can put a lot of freight on Thomas Jefferson. I just gave him credit for being the great articulator of the manifestation of the Enlightenment that shaped the modern world, so you can’t let him off the hook for what he didn’t do.

But it did take a civil war and forty years after he died and six hundred thousand American casualties to abolish slavery. Those of you who come from my native region in the South know that in the lifetime of most of the people in this room, we had to have federal legislation so that poll watchers would not put a box of Tide on a voting table and say to an African American, “You can have a ballot if you can tell us how many flakes of soap are in this box.” So before we’re self-righteous about Thomas Jefferson, I think we should take a moral accounting of ourselves.

DR: One last thing relating to slavery. In recent years, a lot of discussion has occurred about his relationship with a slave, Sally Hemings. He fathered six children with her, and he appears to have been an attentive father to those children, and he more or less stayed with her until he died. How do you explain a slave owner like that having a relationship with an enslaved person? Was that common or not common, and how did he hide it? When it was made public in those days, he never denied it, really, and he never affirmed it. Lastly, based on DNA evidence or anything else, do you have any doubt that the Sally Hemings–Thomas Jefferson relationship was true?

JM: To take them in reverse order, I do not have any doubt. Even in the absence of the DNA evidence, which is 99.9 percent convincing, I do not believe that a man so driven by appetite for power, for books, for food, for wine, for art, for knowledge, could at the age of forty, after his wife died, simply stop short of indulging the most sensuous appetite of all.

If you disbelieve the Sally Hemings story, then you are disbelieving a perennially coherent, oral history tradition from the African American community, and you are ascribing to Jefferson a kind of discipline that is almost superhuman. I do believe that it happened. It was common.

There was an old line of Mary Boykin Chesnut [a South Carolina writer and the wife of a plantation owner], who wrote a diary of a trip through the Carolinas a few years after Jefferson’s death. She pointed out that white women on plantations could tell you with great precision the parentage of any mixed-race children on every plantation in the county except their own, where apparently the children simply descended like manna from heaven. So there was a culture of desire and denial in my native region that was extraordinary. It was extraordinarily pervasive. It’s very hard to put ourselves back there.

It is one of the many hypocrisies of Jefferson’s life. His children by Sally Hemings were the only slaves he freed. Let me just take a second about how the Jefferson-Hemings relationship began.

It began in Paris. Sally Hemings was his wife’s half sister. Let me say that again. Sally Hemings was his wife’s half sister, so the Hemings family itself, in the odd world of slavery, was—and a white southerner really hesitates to use this word—but they were a privileged slave family, as horribly ironic as that statement is. They were to be taken very good care of and overseers were not to give them orders. If I may, they were family. And so when Sally Hemings arrives in Paris, when Jefferson is the American minister there from 1785 to 1789, the relationship begins.

A study in contradictions: the author of the Declaration of Independence was also a lifelong slave owner.

DR: She was fourteen?

JM: No, she was sixteen. Before we go into that, we should point out quickly that James Madison wooed a fifteen-year-old daughter of a congressman from New York. Lock up your daughters. John Marshall married a girl when she was fifteen or sixteen. The age of consent in Virginia in 1800 or so was twelve. Let’s not be anachronistic. We have to put ourselves back in that world, in that time.

In what I find one of the most moving and courageous moments in the whole Jefferson saga, here’s this woman—this girl, as you say—Sally Hemings. She is in Paris, she has become pregnant by the man who owns her, who totally controls her fate, and he wants her to go back with him when he returns home to become the first secretary of state.

If she stays in France, all she has to do is go down to the Paris City Hall and declare that she is a slave being held in France, and she will be free. Her brother is there, he can help her with it.

In what I find to be one of the most compelling moments, she negotiates with one of the most powerful men in the world, and she bends him to her will. She says, “I will go back with you if any children we have are freed at the age of their majority.”

I have friends who are lawyers who say they could have gotten her a much better deal, but I think, in context, her courage, her savvy in some ways, to make the best of what was, I think for everyone in this room, a virtually unimaginably difficult and tragic situation, is a testament to her courage and a remarkable character about which we know almost nothing. But that relationship did last until the day Jefferson died forty years later.

Let me quickly say something about the press—I know, a big favorite of everyone here. Jefferson dealt with this regarding the story of Hemings, beginning in September 1801. He had not been president for a year when the story—almost entirely accurate, with just two little mistakes—appeared in a Richmond newspaper, written by an alienated former ally of his. He denied it. It’s a little unclear what he was denying, but this was very much part of his political life.

There were political cartoons in the newspapers during his presidency with his head on a rooster’s body that called him a philosophic cock, with “dusky Sally,” as she was known, in the background as a hen. I know a lot of you all want to think that cable TV just made this a lot worse, but it’s been a perennial problem.

DR: When Jefferson was at the White House, did Sally Hemings ever visit?

JM: No, no. He was very much embarrassed by his slave-owner status whenever he left Albemarle County. He took slaves to Philadelphia for the Continental Congress, but with the Adamses, who were opposed to slavery, he was very careful about it. He did not want the people in Washington to see him as a southern politician. He wanted them to see him as a national politician.

DR: Let’s move on to the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson writes it in more or less four days. He had seventeen days, but like many people he said, “I’m busy, I waited until the last moment,” and so he spends four days on it. Why was he picked to write this important document? He was only thirty-three years old, relatively young. Who edited it, who else was on the committee with him, and how did that get to be so important?

JM: Well, thirty-three is a good age. Jesus did a lot that year. I don’t think that joke violates the wall of separation between church and state, does it?

Jefferson showed up in Philadelphia in 1775 with, as John Adams put it, “the Reputation of a masterly Pen.” He had written A Summary View of the Rights of British America in 1774. It had gotten wide circulation in the colonies. Nothing like Thomas Paine’s famous pamphlet Common Sense later in 1776, but it was a document that showed, as Adams again put it, a certain “felicity of expression,” and we have to put ourselves back in June 1776.

Everything in the world was going on. They were trying to make a whole new world. Jefferson was on something like six committees, he was in charge of creating a plan for Canadian defense, every kind of legislative question was coming up.

John Adams believed, being a lawyer, that the resolution to reorganize state governments that had passed a few days before had been the real break with Britain that would be celebrated. Only a lawyer could think that way. The Declaration of Independence was kind of an afterthought. It was something they wanted to do, they thought they should do it, so one of the world’s great subcommittees was formed.

DR: With John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Robert R. Livingston from New York.

JM: And Roger Sherman of Connecticut.

DR: Five people. But as I understand it, what they said to John Adams was, “We really would prefer Jefferson to write it,” because Jefferson was from Virginia and the Massachusetts people were seen as being in favor of breaking away, so having this man from Virginia write this declaration might bring the southerners into the fold.

Jefferson sits down, he writes for four days, he brings the draft back to Congress, it’s edited mildly by the committee. Benjamin Franklin made a couple of changes. They decide on July 2, 1776, that we’re going to break away from England. What does the Congress do with the Declaration on July 3 and July 4?

JM: They applied the wisdom of a great legislative body. That was their view. In Thomas Jefferson’s view, they mutilated it.

Those of you who are writers will know that being edited is a great and important and wonderful thing to go through, akin to colonoscopies and other things like that. Jefferson hated it so much, he was sitting next to Franklin on the floor there in Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, and his leg started doing this jiggling. Franklin had to reach over and put his hand on his leg to calm him down, because Jefferson thought the document was being torn apart.

The one great edit, I think, which came in the subcommittee process, was made by Franklin, who was suffering from gout at that point—the wages of a well-lived life. He changed the word sacred to self-evident—“that these truths are self-evident”—in order to ground the notion of human rights more in the ethos of reason than in the ethos of religion. He thought that would work better over time. It was a critical change that Jefferson enjoyed.

Adams and Jefferson, we remember them now in this great autumnal correspondence—they’re the great rivals who came back together and exchanged almost two hundred letters in their retirement. But Adams never really got over how, as he put it, the Declaration of Independence was a theatrical show and Jefferson ran away with all the glory of it, and so that was part of the rivalry that really never went away.

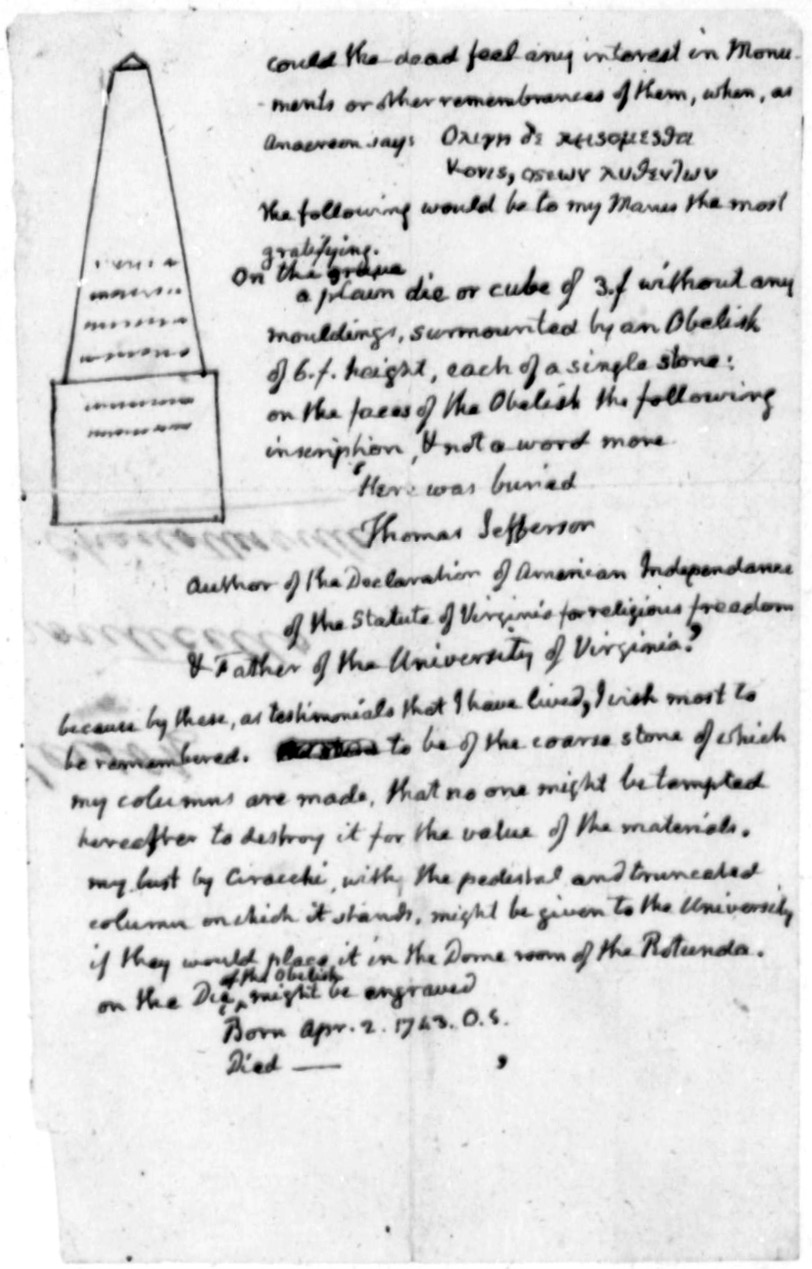

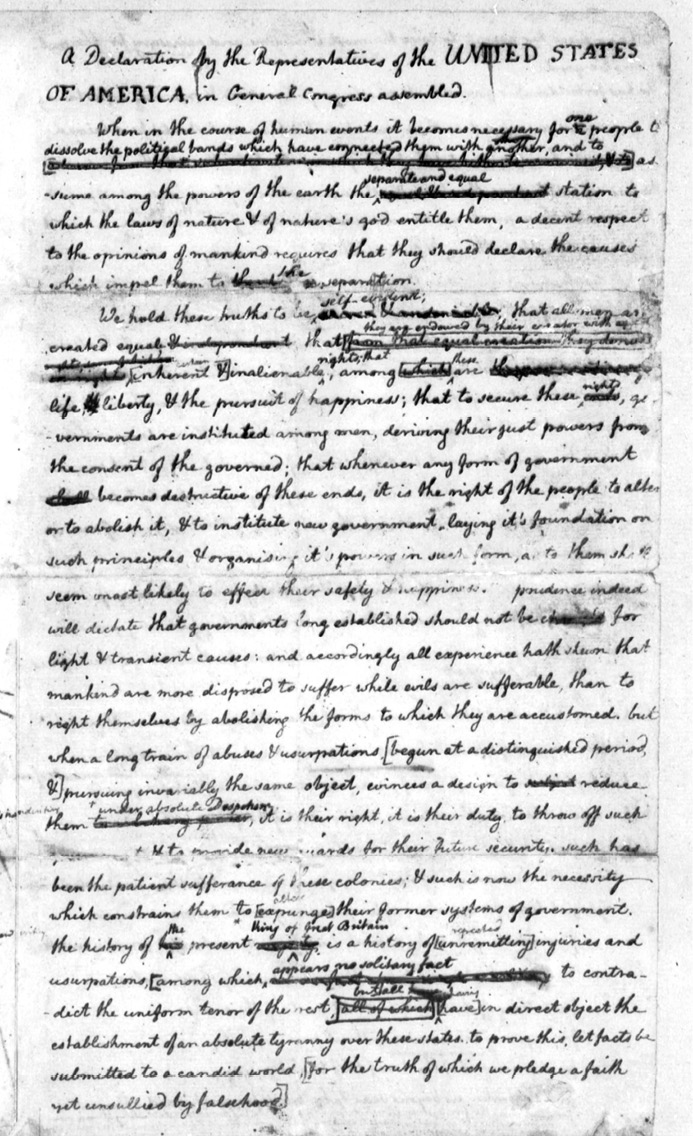

Jefferson’s rough draft of the Declaration of Independence from June 1776 includes edits made by John Adams and Ben Franklin, among others.

The Declaration of Independence has three parts to it. First is the preamble, which I gave a little bit of before: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” Nobody paid attention to that. That was not important then because it was just a preamble.

The part that was most important was the section that listed the faults of King George III. That was what most of the document dealt with. The mutilation that occurred was the Congress’s taking out Jefferson’s view that King George should be blamed for the slave trade. He blamed King George for forcing slaves into the United States. It was taken out because many of the people in the Congress were slave owners, and they didn’t really like to criticize King George for it.

Then the third part of the Declaration stated that we’re going to become independent. Those were the three parts.

Thomas Jefferson, not being unlike many of us, perhaps—at least, not unlike me—he would send his friends a copy of his draft and say, “Don’t you think my draft is better than what these guys did?” So he wasn’t above all that.

Let me describe what you’re actually seeing when you see a copy of the Declaration of Independence. The language of the Declaration was agreed to on the Fourth of July. In those days, they didn’t have typewriters and things like that, so once they mutilated the language—I should say that Jefferson was so upset that for nine years he didn’t admit that he wrote the Declaration of Independence. He wouldn’t tell anybody, he was so upset about it. Later he said it was the most important thing he did, and he put it on his tombstone.

But, okay—the language has been agreed to. They went next door to a man named Mr. Dunlap and said, “Print up a hundred copies of this” as a broadside—a Dunlap Broadside, as they are now known—and they took these hundred copies and distributed them around—one to King George, one to George Washington to read to the troops at Valley Forge, and then they were sent around to the states.

There were two hundred of them. There are twenty-seven known copies. They probably are worth about $25 million apiece now.

The broadside version doesn’t have any signatures. It just was the text. They had to inscribe it, so what happened?

Well, they told all the members who agreed to the final document on July 4, “Go home, because one of the states hasn’t agreed to it.” New York State had been invaded by the British, so the legislators were hiding, and they hadn’t agreed to the independence. So the Congress ultimately said, “Let’s get all thirteen states together. We’ll come back at another time when New York can be in favor of it and everybody can sign it.”

They came back, more or less around August 4. There are debates on whether it was signed then or not, but let’s just assume for a moment it was signed on August 4.

That document was kept as part of the United States government. It was moved to New York and back to Philadelphia; it was wrapped up for a time, hidden in a box. When the British invaded in 1814, it was wrapped up and taken in a cloth bag down to Leesburg and hidden there. At one point it was displayed for thirty years in a building in Washington—the Claims Building.

The original is now in the Archives. If you go to the Archives, what you see is a very faded document. One of the reasons it’s so faded is because it was exposed to sunlight—nobody preserved it—but another thing also happened.

In 1820 John Quincy Adams, the secretary of state, said, “We’re not going to have a copy that everybody can see, because it’s getting faded.” He hired a man named William Stone and said, “Figure out how to make a perfect copy of the Declaration of Independence.”

So Mr. Stone, in a three-year process, came up with a process that essentially involved taking a wet cloth and putting it on the original. That took half the ink off, and that was then made into a copper plate. That copper plate was then used to make two hundred perfect copies—two hundred—two were given to each living signer of the Declaration, and two or more to each state or governor.

There are fifty or so of them left. When you see the New York Times, on the Fourth of July, printing a copy of the Declaration of Independence, what you’re seeing is a Stone copy. It’s a perfect replica, but it’s a Stone copy because the original one is so faded. So today, when people talk about the Declaration, there’s the original in the Archives, there is the Stone copy, and then there are the Dunlap copies that were printed the day after, which don’t have signatures.

And the signatures had no binding effect. The Declaration was a propaganda document, but everybody wanted to make sure that, in effect, the signers were really standing behind it. They all knew when they signed it they might be signing their death warrant, because it was treason. So that’s more than you might want to know about the Declaration.

Now, how many Stone copies do you have?

DR: I own four of them [now seven], and I’ve given one on permanent loan to the State Department.

JM: That’s one more than me.

DR: One is in the permanent display at the State Department. If you go to the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, it’s there. One is at the Archives, one is at Mount Vernon, and one is now at the new Constitution Center in Philadelphia. I put them on display so people will see them.

JM: Can I give you one treason story?

DR: Go ahead.

JM: When the signing of the Declaration was going on—I have this vision in my mind that it was on a table in the corner and you would come in for a roll call and they would say, “Have you signed this?”—it was like a birthday card—“Have you signed it yet?” and they would go over and do it.

There was a great fat Virginian named Benjamin Harrison and a little, little guy from Massachusetts named Elbridge Gerry, of gerrymandering fame, a wispy fellow. And as they were taking their turns, Harrison turned to Gerry and said, “You know, when the British catch us and hang us, it’ll all be over with me. You’re going to dangle for days.” So there was the sense that if they didn’t hang together, they would hang separately.

DR: Thomas Jefferson, when his document was being mutilated, never said a word because he didn’t like to talk. As president of the United States, he gave one speech in public. He hated to talk in public. Why was that?

JM: He wasn’t very good at it. Honestly, he did not have a voice that carried.

As keen an observer of Jefferson as John Adams—and as we all know, our frenemies are often our best critics and the most precise ones—believed that Jefferson’s political power was enhanced by his failure to be a great speechmaker. Remember, in those days, the largest group he would have addressed—outside of the presidential inauguration, which would have been a big crowd—would have been the House, the Continental Congress, or the Confederation Congress. It would have been a group of people fewer in number than are in this room.

Adams—and Franklin also agreed with this—said that because Jefferson was such a good committeeman, he was a good draftsman, he would exercise a certain amount of power in being the fellow who wrote the report. It enhanced his power, because no legislator had ever changed his mind.

Adams spent most of his time getting up and giving speeches saying the other guy was wrong, and it never changed anyone’s mind. And so both Franklin and Adams, on reflection, believed that Jefferson had been wise not to pursue the art of rhetoric.

DR: In those days, you ran against each other for president, and whoever came in second became vice president. In this case, when Adams ran against Jefferson in the election of 1800, Adams got the highest number of votes, and he became president. How was it to be serving as vice president for somebody you ran against?

JM: It didn’t work out very well, surprisingly. This was the first great contested election in U.S. history, because Washington had not faced any opposition and yet was so sensitive to criticism that he almost left after one term because he didn’t like being criticized at all. I certainly never have that reaction to criticism.

Adams came to call on Jefferson when he arrived after the 1800 election and said, “I very much want you to be part of the councils of the administration.” They talked about several issues, and then Adams went off to have dinner with a bunch of Federalists and, as Jefferson put it, “We never again had a substantive discussion about any measure of the administration.”

The Federalists are holdovers. John Adams kept Washington’s cabinet, and later said it was one of his greatest mistakes because they were more loyal to older policies than to Adams’s.

DR: So when Adams ran for a second term, he was defeated by—

JM: Thomas Jefferson.

DR: And Jefferson’s vice president was?

JM: Aaron Burr.

DR: And Aaron Burr shot Hamilton while he was vice president?

JM: In 1805.

DR: When Aaron Burr was vice president, was he preparing an insurrection against the president because of the Louisiana Purchase?

JM: There were several insurrections. In 1801, beginning in February, there were thirty-two ballots cast in the House of Representatives for the presidency of the United States. There had been a mistake. It took the Twelfth Amendment to correct it, but in 1800 the number of electoral votes for Jefferson and Burr turned out to be the same.

In the past, they would figure out a way to throw away a vote, vote for someone else, just symbolically. It hadn’t happened this time.

There’s a great debate about this, but Burr was not as eager to stand down as a possible president as Jefferson had hoped, and so you had this entire intrigue in February. There was a snowstorm in Washington. Jefferson was in a quiet agony over at Conrad and McMunn’s boardinghouse at C Street and New Jersey Avenue, a fancy new boardinghouse, just trying to figure out how to survive this great political intrigue. Burr let it be known that perhaps he would accept the presidency.

In one of the moments that helped feed an existing rivalry between John Marshall, a cousin of Jefferson’s, and Jefferson, there was talk that Marshall might become president for a year while they settled this. You can imagine how that made Jefferson feel about Marshall.

As someone once said, for some reason God loves drunks, little children, and the United States of America. This was the fourth election we’d ever had. Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania and James Monroe of Virginia were governors who prepared to send militia to Washington if, in fact, Thomas Jefferson was not made president. It was a remarkably conditional moment.

DR: Jefferson lived in the White House for eight years—two terms—and his hostess was Dolley Madison because he didn’t have a wife, is that right?

JM: That’s right.

DR: He didn’t give speeches, so members of Congress would come to the White House for salons, and he would greet them in his slippers. What was that all about?

JM: He very much wanted to establish a republican—lowercase—ethos. A lot of debates in the first four, five, six years, even the first decade of the Republic, were about these questions of style and etiquette.

Washington was much more monarchical than a lot of Republicans believed he should be, understandably. General Washington wore a sword when he took the oath of office both times; John Adams also wore a sword. I always have visions of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Pirates of Penzance in my mind with that.

Jefferson refused to do that. Jefferson walked from Conrad and McMunn’s to the Capitol to take the oath of office and then returned after his inaugural address and sat down at the common boardinghouse table to have lunch, a very conscious way of signaling that this was a republic, not a proto-monarchy.

The way in which he entertained at the White House was very much like this, and also classically contradictory in a Jeffersonian way. There had never been better food, there had never been better wine—he went broke buying wine for the White House to keep members of Congress happy—but he would show up in these sort of Virginia plantation-house clothes, showing that any farmer could become president.

DR: Jefferson almost went broke all the time. He would die bankrupt, more or less. Why was he always borrowing money, and how come he was so bankrupt if he was so smart about so many other things?

JM: You’re a private-equity guy. You know farmers.

He was a plantation owner, and he was not very good at it. He spent a lot of time creating new things. He created new species of apples, he loved grapes, he was always trying to bring Italian musicians to Albemarle County, Virginia. It was all very charming, but he didn’t actually get a crop to market very often.

DR: You spent five years studying him. If Thomas Jefferson were sitting right here now and you had a chance to ask him one question, what would that question be?

JM: “Why, given your clear moral sense that slavery was the fire bell in the night that was going to lead to a civil war someday, did you not use any political capital in the twenty years of your political dominance to try to ameliorate the situation?”

He just gave up. Again, no one was more eloquent, even in retirement. If you go to the Jefferson Memorial, all those quotations, almost all of them, are about slavery: “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just.” “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people shall be free.”

These are all about slavery, but these were always in letters in which he then said, “But I can’t do anything about it. It’ll be the work of another generation.”

Thomas Jefferson was the dominant political figure of the first half of the American Republic. I absolutely believe he was the most important president—Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln.

From 1801 through 1840, for those forty years, either Thomas Jefferson himself or a self-described Jeffersonian was president of the United States, except for four years during the administration of John Quincy Adams. For thirty-six years there was a de facto Jeffersonian dynasty. No other president has done that. Lincoln didn’t do it, Roosevelt didn’t do it, Reagan didn’t do it. It’s an unmatched achievement.

If I’m right about that, then you have to take unpopular positions at times to move the country forward in places they don’t want to go, and Jefferson just never tried. So “Why, Mr. President, did you never try?”

DR: I wish I knew the answer. One last question. Jefferson lived to be eighty-three years old—a very old age in those times, when the average life span was forty-five or forty-seven. He would attribute that to riding horses and walking, but he also did something with water every day with his feet. If you want to live to eighty-three or longer, what is the secret that he used?

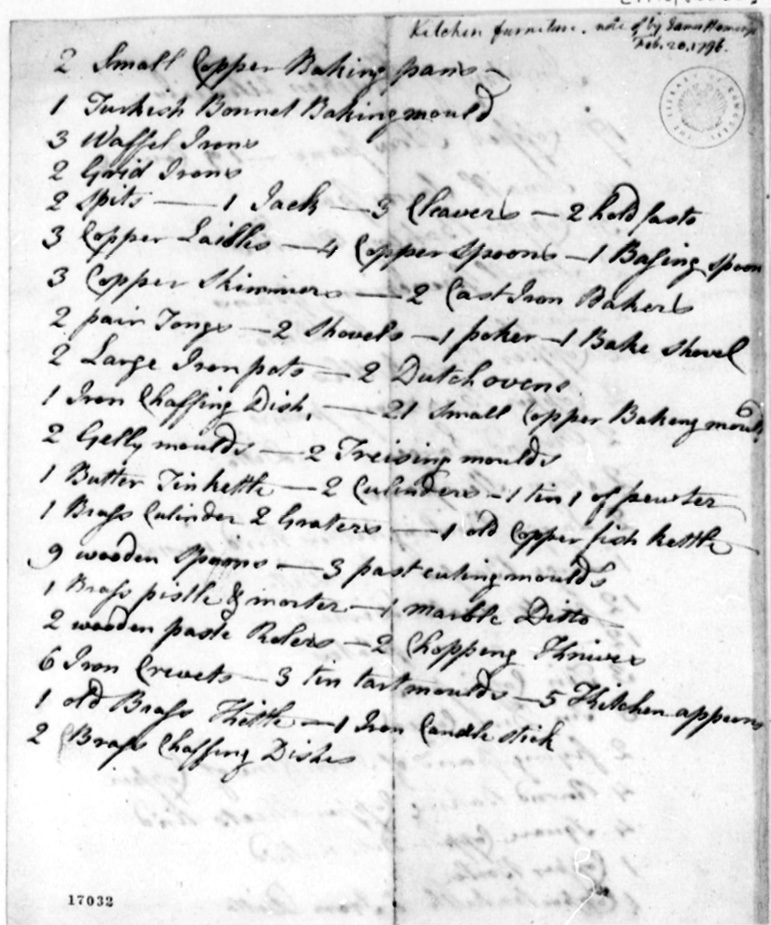

James Hemings, a relative of Sally Hemings, was trained as a French chef. He prepared this inventory of kitchen utensils in 1796, two weeks after he was emancipated by Jefferson.

JM: I’m glad you asked that, because I’m investing in a small company to create foot bowls.

I was allowed, through the good graces of Monticello, to spend the night in Jefferson’s bedroom in the course of doing this book. Nothing inappropriate happened with anyone, I quickly, quickly add.

But one of the things I learned, because I slept on the floor next to the bed, is there was this groove next to the bed. I asked the curator—marvelous staff there, marvelous people—I said, “What is that?” And she said, “Oh, that’s from the foot bowl,” as if I were a lunatic for not knowing this.

Every morning a bucket of cold water was brought to Jefferson’s bedside and he plunged his feet in. And they were little feet. We looked at his boots recently, actually. They were tiny, but he was tall, above six feet. He plunged his feet into cold water and left them in for a few minutes. Benjamin Franklin did the same thing, and he lived a long time too.

He also didn’t eat a lot of meat, and he avoided hard liquor, although four glasses of wine was just the beginning of a good time in Jefferson’s house. Soak those feet in cold water, and you too can live to be eighty-three years old.