Hamilton’s birthplace on the Caribbean island of Nevis.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): We’re going to delve into a conversation on our first treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, with the man who’s written what I think is the definitive biography of him. How many people here have read the biography? How many people have seen the play? How many people are looking for tickets to the play?

When you were writing this book, did you ever think it would be made into a show?

MR. RON CHERNOW (RC): I think it’s safe to say, David, I never thought it would be made into a musical, much less a hip-hop musical.

DR: But Hamilton was based on your book.

RC: Yes, it’s very faithfully based on the book.

DR: The producer read your book, or the lyricist read it?

RC: Lin-Manuel Miranda, who stars in it—he wrote the lyrics, the music, and the book for the show—read the book back in 2008. When I met Lin-Manuel, he told me that he had been reading my Hamilton biography on vacation in Mexico, and he said that as he was reading it, hip-hop songs started rising off the page. Needless to say, this was not a typical reaction to one of my books. But he has produced the most extraordinary show I’ve ever seen.

DR: How long did it take you to research the book, and how long to write it?

RC: The book took me five years to write, which seems like a long time, but you have to understand that Alexander Hamilton was the most prolific author of all time. He died at age forty-nine, and yet he left behind thirty-two thick volumes of personal, political and business papers. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton was published by Columbia University Press, and the chief editor, Dr. Harold Syrett, made the facetious statement that he wanted to dedicate the volumes to Aaron Burr, without whose cooperation the project could never have been completed.

DR: When we talk about the Founding Fathers, we often say Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Franklin. But Hamilton hasn’t historically gotten the deification the others have. Why do you think he wasn’t as well recognized for his accomplishments, given all the things he did?

RC: When I tell you, David, that Alexander Hamilton’s political enemies were John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe—and I’ll even throw in John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson—what do you notice about that list? It sometimes seemed like the fastest road to the White House was to be a political opponent of Alexander Hamilton.

What happened is that Hamilton died in 1804. He never reached the age of fifty. If history is written by the victors, the victors were certainly the Jeffersonians who dominated American politics in the years leading up to the Civil War. No less important, I think, is that Hamilton’s party, the Federalist Party, disappeared in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, so there wasn’t an institutional structure perpetuating his memory.

DR: Of all the Founding Fathers I mentioned, the only one who was not born in the United States was Alexander Hamilton. Can you go through the story of his birth and how he was considered by some to be illegitimate, and how that affected him?

RC: This was a really ghastly Dickensian childhood. Hamilton was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis and spent his adolescence on the island of St. Croix. Hamilton’s father, James Hamilton, abandoned the family when Alexander was eleven. His mother, Rachel, died when Alexander was thirteen. He was lying there inches away from her, deathly sick himself.

But he survived. He was farmed out to a first cousin, who committed suicide a year later. He was then sent to live with a planter named Thomas Stevens, whose son, Ned Stevens, became his best lifelong friend. Everyone who saw Ned in later years was shocked by the uncanny resemblance between him and Alexander Hamilton, so in all likelihood, Hamilton’s biological father was actually Thomas Stevens.

He was clearly illegitimate. His mother, Rachel Faucette, came from a French Huguenot background. She had already been married when she met James Hamilton and, under the terms of her divorce, she could not legally remarry, so any children she had were illegitimate, and there was a tremendous stigma to that at the time.

DR: How does somebody whose mother was gone and whose father abandoned him make it from the Virgin Islands to the United States? How did that happen?

RC: What happened was that Hamilton was a poor clerk working at a trading house on St. Croix when a killer hurricane hit the island in 1772. It was a monstrous hurricane. It’s thought that a tsunami rolled across the island. Hamilton sat down and he published a description of the hurricane in the local newspaper, and it was almost Shakespearean in its vividness.

The local merchants read this, recognized the extraordinary literary flair of this young man, banded together, and took up a collection to educate him in North America. He came to America around 1773—in other words, right on the eve of the American Revolution. He didn’t know a soul, just came armed with a few letters of introduction. He was briefly educated in New Jersey and ended up in King’s College, now Columbia University, which was then on the southern tip of Manhattan.

DR: He was in New York and going to college, paid for by friends and admirers. When did other people realize that he was a gifted writer and talker?

RC: Almost immediately. Alexander Hamilton was someone who radiated genius.

I remember a wonderful statement that Dr. Samuel Johnson made about Edmund Burke. He said that if there was a rainstorm one day and you sheltered under an awning with Edmund Burke, whom you had never met before, if you sheltered under an awning with him for five minutes, you would know that you had been in the presence of a genius. That describes the reaction people had to Hamilton.

He was an undergraduate at King’s College, but he was already publishing fiery essays against the British and making rabble-rousing speeches in what today is City Hall Park. And then, as the Revolution started, he became the head of an artillery company, drilling in St. Paul’s churchyard.

DR: Did he just start the artillery company himself and say, “Join me”?

RC: Originally it was a group of students.

DR: He was in the artillery company, fighting in the Revolutionary War. How did he wind up as the chief of staff to George Washington?

RC: As a soldier and as the head of this artillery company, Hamilton was a daredevil. He was physically fearless at the Battle of White Plains in 1776, and as the Continental Army was retreating across New Jersey to the Delaware after the battle, Hamilton was covering the retreating soldiers. He was spraying the British and Hessian soldiers with fire.

So he came to Washington’s attention first, I think, for his derring-do, but also because of his brilliance. There were four generals who tried to recruit Hamilton onto their staff, because he was so literate and capable. From Washington’s standpoint, Hamilton had an ideal combination of talents. He was already a very skilled soldier, but Washington’s most pressing need was for someone to write letters for him.

DR: Because the generals in those days were writing dispatches all the time, and Washington had something like four people doing this for him?

RC: He had a number of people doing it. To give some sense of how important these letters were, during the eight and a half years of the Revolutionary War, Washington was serving fourteen different political masters. He was keeping up extensive correspondence not only with the Continental Congress but with the governors of the thirteen states.

Hamilton was handling this correspondence, which was even more important once we forged the alliance with France. Hamilton’s mother was a French Huguenot and he was therefore bilingual. When he was exchanging letters with the marquis de Lafayette, he would write to Lafayette in faultless French. Lafayette would send back letters that even I could see were full of spelling and grammatical mistakes in French.

DR: So Washington brought Hamilton onto his staff, and he quickly rose up to be not just a letter writer but, in effect, the chief of staff?

RC: It was quite remarkable. When you look at the lists of generals at the different war councils before the major battles, you have something like eleven generals, and then it will say “Colonel Hamilton” on the bottom. This was very important in terms of Hamilton’s career, because he was getting a really expansive view of the Revolutionary War, both from a military and also a political standpoint. This was his school.

DR: So he was running the war, practically, for Washington. He was Washington’s mouthpiece.

RC: Well, not exactly running the war, but weighing in on all sorts of issues.

DR: Why was he not happy with that? At one point he said, “I want to do something else.” What was it he wanted to do?

RC: Alexander Hamilton realized from the very beginning of the war that postwar political glory would not go to the person who had written the most beautiful letters for Washington during the war but would go to battlefield heroes. Throughout the war, he was lobbying Washington to give him a battlefield command. It produced real friction between them, and Hamilton ended up leaving Washington’s staff.

Hamilton finally got Washington to give him a field command at Yorktown, and at last he had the moment he’d always fantasized about. He was assigned to take a defensive fortification.

It was at night. He rose up out of the trenches, with shells exploding in the air, and led his men across this rutted battlefield. When they got to Redoubt No. 10 [a key part of the British defenses], Hamilton had one of the men in his company stoop down. He stood on the guy’s shoulders, sprang up on the parapet, and yelled to the other men to follow him. It was almost like a scene from a Hollywood action flick. That was the life of Hamilton.

DR: And he became a bit of a hero for this.

RC: Absolutely.

DR: The Treaty of Paris took another two years or so to negotiate, but after Yorktown the war was over, more or less. What did Hamilton do?

RC: What happened was Hamilton went back to New York. He was a great one for taking advantage of opportunities. Robert Morris, who was the superintendent of finance for the United States, appointed him tax receiver of New York.

This would have been a very lowly job for anyone else, but Alexander Hamilton lobbied the New York legislature to create a special committee on how to make tax collection more efficient. Hamilton so impressed the New York State Legislature with his presentation that he was appointed one of the five New Yorkers at the Confederation Congress [the U.S. governing assembly from 1781 to 1789].

DR: He was also practicing law. He got to become a lawyer without going to law school, right?

RC: It was amazing, because at the time you became a lawyer by serving a two-year apprenticeship with an older lawyer. Hamilton passed the bar in New York after six months of self-study. He cobbled together a digest of New York legal precedents and procedures that was so expertly done it became a crib sheet for law students for another two or three generations in New York.

DR: In those days, if you came from a foreign country and you were, let’s say, illegitimate, you were not likely to rise up in New York. How did he manage to get to the top of New York society?

RC: He married Elizabeth Schuyler, whose father, Major General Philip Schuyler, was not only one of the leading generals in the Revolution, he was a close friend of George Washington, and one of the leading landholders in New York State.

I think what happened, David, was that because Hamilton was Washington’s chief of staff, even though he was this illegitimate orphaned kid from the Caribbean, it was like being chief of staff of the White House. It gave him tremendous standing.

When Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler at the Schuyler mansion in Albany, the place was teeming with all her rich relatives—the Van Cortlandts, the Van Rensselaers, the Beekmans. They were the Anglo-Dutch royalty of New York State.

Hamilton didn’t have a single family member there. He had only one friend, a James McHenry from Washington’s staff. So you can imagine the discrepancy in status. He was marrying into the most social and prosperous family in New York, and he had only one friend present.

DR: He had a bit of an amorous reputation. In fact, what did Martha Washington call her tomcat?

His marriage to Elizabeth Schuyler, a member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, raised Hamilton’s social status considerably.

RC: Hamilton. Yeah, it was a big joke. She had this feral tomcat that she called Hamilton, although historians have disputed the accuracy of this.

Everyone noticed early on that the ladies were fatally attracted to him. In fact, Abigail Adams, after she met Hamilton, said, “The devil is in his eyes. His eyes are lasciviousness itself”—what we would call “bedroom eyes.” Hamilton clearly had a roving eye.

DR: So the war was over. We signed the Treaty of Paris. The Articles of Confederation were governing the country, and Hamilton was a member of the Congress. What could be better than that? He was making a lot of money as a lawyer. He’d married into a prosperous family. Why did he decide to try to overturn the Articles of Confederation?

RC: For one thing, throughout the war, Hamilton and Washington were constantly writing letters to the Congress and the state governors, pleading for men and money. The Continental Congress did not have the power to demand money from any of the thirteen states. They did not have the power to demand men from the states. They could only request. And of course all of those thirteen state governors decided that they would rather keep the money and men in their own states. So Hamilton already saw the weakness of the Articles of Confederation.

When he was in the Confederation Congress, it had no independent revenue source. They tried to enact a 5 percent impost—a 5 percent customs duty. They could not get that passed. Hamilton, I think, despaired of the Articles of Confederation as ever being the framework for a real government.

DR: So he and Madison caballed to put together an effective request for a constitutional convention.

RC: They met in Annapolis, Maryland, in late 1786. There was a small conference called to try to iron out trade disputes. There was no common trade policy, so Connecticut had its own import duties, as did New York, as did New Jersey, etc.

What happened at this little conference in Annapolis was that they realized the disputes over trade policies were just symptomatic of the basic problems with the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton personally wrote and issued the plea for a constitutional convention to meet in Philadelphia in May of 1787.

DR: Congress agreed to have a constitutional convention that might modify but not completely change the Articles of Confederation. The trick was getting George Washington to show up. Why was that so important?

RC: They realized that Washington would give the convention a cachet it couldn’t possibly have otherwise. Hamilton and Madison at that point were comrades in arms, but that changed. This was the one relationship where someone went from being Hamilton’s political friend to political enemy.

But at that point they were working very, very closely together, and they realized that technically the Constitutional Convention was supposed to revise the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton and Madison saw that was ridiculous—that they needed to scrap the Articles of Confederation and create a brand-new constitution. That was obviously going to be something that would be hard for the general public to swallow, so they felt that it required someone of George Washington’s stature to reassure the country that this was not some sinister plot being hatched in Philadelphia.

DR: Hamilton convinced Washington to go, and he showed up at the Constitutional Convention. They met for three months. What was Hamilton’s role in the convention? He wasn’t really that powerful, was he?

RC: In the opening weeks of the convention, Hamilton didn’t make a single speech. When he finally opened his mouth, being Alexander Hamilton, he spoke for six straight hours. He presented his own plan for a new form of government, and it was frankly pretty wacky. It was not his greatest moment.

For the presidency, he wanted to have an elective monarch, essentially. He wanted the president to be elected but then to serve for life, subject to impeachment or recall. It was a terrible idea, but luckily it was not taken seriously. Then Hamilton got down to the serious business of passing a more realistic proposal.

DR: At the Constitutional Convention, each state had one vote, and there were two people in the New York delegation who were against his views. Hamilton was always outvoted, so he didn’t show up that much, did he?

RC: Right. The New York State governor was a man named George Clinton, who was a real local boss. George Clinton loved the Articles of Confederation. The weaker the central government, the more he liked it, so he was afraid of the Constitutional Convention.

There were three delegates from New York: John Lansing Jr., Robert Yates, and Hamilton. Lansing and Yates were sent by Governor Clinton essentially to sabotage the Constitutional Convention. It wasn’t until a certain point, in the middle of that summer, when Lansing and Yates left the Constitutional Convention for good, that Hamilton suddenly came back, realizing his moment had come.

DR: When the convention agreed on the Constitution, Hamilton agreed to it even though he thought it wasn’t perfect. Why?

RC: People often say, “Well, the final document was so different from his speech,” but the final version of the Constitution differed in significant ways from the views of every single person there. Hamilton’s elective monarch was wacky, but Madison wanted the federal government to have a veto over every state law—not exactly a great idea either. Benjamin Franklin wanted a plural executive—that is, instead of one president, we would have a council of three, which I think we will all agree was not a great idea. The beauty of this situation was that all of these men were able to then rally around this compromise document.

DR: As drafted, the Constitution said that it would go into effect if nine of the thirteen states ratified it. What was Hamilton’s role in the ratification process?

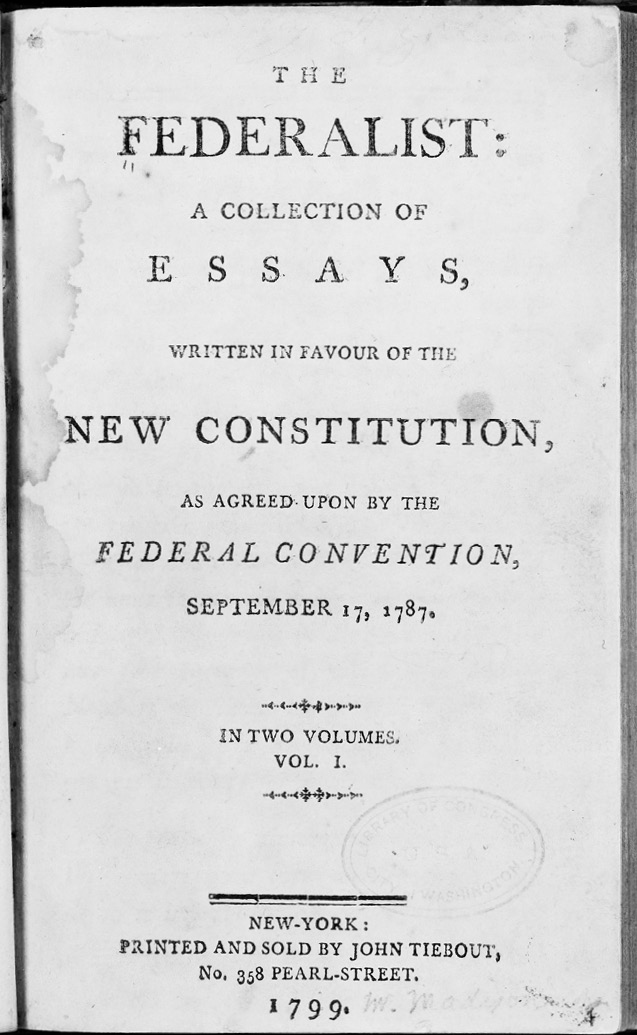

RC: Major. First of all, it was Hamilton who originated the idea for The Federalist Papers, basically because New York was one of the states with significant opposition to the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers were eighty-five essays published over a six-month period. [Written by Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay and published under the pseudonym Publius, the essays argued the case for ratifying the Constitution.] Alexander Hamilton wrote fifty-one of them, and he was doing this as a sideline. He had a full-time legal practice. We have anecdotal evidence of the printer sitting in the outer office as Hamilton was finishing the final lines, and then the printer would run off to publish them.

DR: The Federalist Papers were written, the Constitution was ratified and went into effect, and George Washington was then elected president of the United States. There was no provision in the Constitution for a cabinet, but Washington decided to have one. Why did he decide to have Hamilton be his secretary of the treasury, and was that the job Hamilton originally wanted?

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay made the case for the Constitution in a series of eighty-five public essays, The FedAveralist Papers. Hamilton wrote fifty-one of them.

RC: I’m sure that was the job that Hamilton wanted. The story is told—how accurately I’m not sure—that as Washington was en route to New York in 1789 for his first inaugural, he stopped off in Philadelphia and asked Robert Morris to be the first treasury secretary. Morris had been the financier of the Revolution. He used his own personal credit to finance the American Revolution.

Morris declined the job. He was already running into serious financial problems that would land him in debtors’ prison in a few years, and he suggested Hamilton. Washington supposedly said to Morris, “I didn’t realize that Alexander Hamilton knew so much about finance,” and Robert Morris said, “To a mind like his, nothing is amiss.”

I think Washington knew all about Hamilton’s knowledge of finance. So Hamilton, at age thirty-four, became the first treasury secretary, which was far and away the most important job in the cabinet.

DR: The cabinet then had three people.

RC: Effectively, yes. Even the attorney general was a part-time legal advisor. There were three cabinet secretaries. Thomas Jefferson, the secretary of state, started out with six people in his department. Henry Knox, the secretary of war, started out with twelve. Alexander Hamilton, because he had customs inspectors and revenue collectors, suddenly had hundreds of people, so his department was more than 90 percent of the entire government.

DR: He created the U.S. Mint and the U.S. Coast Guard at the same time. How did he do that?

RC: The main source of government revenue at the time was from customs duties, so Hamilton created a customs service. There was a lot of smuggling, so he created a fleet of revenue cutters to intercept smugglers. That fleet of revenue cutters became the Coast Guard. Hamilton was really more like the prime minister than just treasury secretary.

DR: One of the big issues was who was going to pay off seventy-some million dollars of Revolutionary War debt. Hamilton had a plan, and ultimately there was a compromise at a famous dinner. Can you describe what happened?

RC: Again, just let me say that the United States was literally bankrupt when Washington was sworn in as the first president. American debt was selling at ten or fifteen cents on the dollar.

Any other regime after a revolution would have just repudiated the debt. Hamilton felt that, as a matter of both American honor and American pride and American credit, that debt had to be paid off in full at par value. The centerpiece of his plan was to assume state debt. There was $50 million in federal debt, $25 million in state debt.

It seems counterintuitive. Why would any treasury secretary voluntarily take on additional debt? Hamilton realized that, if he assumed state debt, the federal government forever after would have a lock on the main revenues of the country. To this day, I think that that assumption of state debt is the reason we pay more in federal taxes than in state and local taxes.

Now, Hamilton had a lot of trouble getting that through Congress, but he struck a deal over dinner with Jefferson and Madison. He agreed to have the new U.S. capital on the Potomac River if they would get him a few extra votes from the South on the assumption of state debt by the federal government.

Thomas Jefferson later said it was the single biggest mistake of his political career. It sounded like a technocratic thing, the assumption of state debt. He didn’t realize that Hamilton had a whole political agenda buried in that to strengthen the central government.

DR: At the time, the capital was New York. The agreement was it would then go to Philadelphia for ten years. And after those ten years, Washington, D.C., would be built. We’re here because of that dinner. After George Washington got reelected, Hamilton decided to stay for how much longer?

RC: Hamilton stayed one year into the second term and went back to being a lawyer in New York.

DR: Why did he leave?

RC: This will not come as a surprise to anyone in this room. He’d made tremendous financial sacrifices for public service.

DR: The salary of the secretary of the treasury in those days was—

RC: It was very low.

DR: Two or three thousand dollars?

RC: Yes. He could make much, much more money as a lawyer in New York. Alexander and Eliza Hamilton ended up having eight children, so he had a lot of bills.

Also, to give you some idea of the success of his program, when he became treasury secretary, we were the deadbeat of world finance. We were in arrears on both the principal and interest on our debt. By the time that Alexander Hamilton left the Treasury five years later, we commanded interest rates as low as any country in the world. Our credit was as high as any of the Western European powers.

DR: When they were in the cabinet, Jefferson was secretary of state and Hamilton was secretary of the treasury. How bad was the relationship? Did they ever get along?

RC: No. Hamilton later said that from the day Jefferson arrived in New York, Jefferson was gunning for him. It was partly there was certainly a personality difference between them. Jefferson was a rather shy, courtly person. Hamilton had a real zest for political combat and polemics.

But they also had two fundamentally differing visions. In terms of the economy, Jefferson wanted a nation based on small towns and traditional agriculture. Hamilton wanted that plus large cities, stock exchanges, banks, factories, corporations—in other words, the world that we know today.

Then there was also the political difference. Jefferson wanted a weak central government, legislative power, strict construction of the Constitution. Hamilton wanted a strong central government, executive power, and a very expansive interpretation of the Constitution. They really started the debate we still have.

DR: In those days, even if you were in the same president’s cabinet, you apparently hired surrogates to write negative articles about other people in the cabinet.

RC: While he was treasury secretary, Hamilton liked writing articles under Roman pseudonyms, which was fairly common at the time. In the middle of one controversy, he started secretly writing essays praising the treasury secretary under the pen name of Camillus.

Then he launched another series under the pen name of Philo Camillus. And Philo Camillus kept praising Camillus, and they both kept saying that the treasury secretary was the most brilliant man in America.

DR: What did they say about Jefferson?

RC: Much less complimentary things.

DR: Madison and Hamilton cooperated on writing The Federalist Papers. How did that relationship go later on?

RC: It sank over an issue that was known as discrimination. I mentioned that the debt was selling for ten or fifteen cents on the dollar. Hamilton announced his plan to redeem all the debt at face value, and the value of that debt soared.

A lot of it was originally in the form of IOUs that had been given to soldiers during the Revolutionary War. Many of them, desperate for money after the Revolution, sold those pieces of paper at depressed prices. Speculators gathered them up and made a killing on Hamilton’s plan.

Madison said, “Let’s track down those original soldiers who sold their IOUs. They should be the ones who profit from the appreciation in value.” Hamilton opposed the idea, even though he was the one who had been a soldier during the war, not Madison.

Hamilton said two things. He said, number one, tracing back all the owners of a security administratively would be a nightmare. The second point was much more important. He said, “I understand that this is hard to swallow, but we have to establish forever the principle that anyone who owns a stock or a bond or any kind of security has, in purchasing that security, assumed all of the risk and all of the reward for it.” So it’s really the basis of our modern financial markets.

DR: George Washington decided not to run for a third term, and he gave a farewell address. Did Hamilton write that farewell address?

RC: Yes, Hamilton did write the farewell address.

Washington gave him two options. He had thought of stepping down at the end of his first term, and he’d had Madison write a farewell. He gave Hamilton Madison’s farewell address and said, “You can either revise Madison’s farewell address or trash it and start anew.”

Anyone who knew Alexander Hamilton knew what decision he would make in that situation. He wrote a completely new farewell address.

He used to tell the story that he and Eliza were walking down the street in New York one day after it had been published in pamphlet form, and a vendor on the street tried to sell him a copy of Washington’s farewell address. He turned to his wife afterward and laughed. He said, “That man tried to sell me a copy of my own writing.”

DR: Hamilton wanted to retain political influence. When Washington stepped down, the next election was between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. What role did Hamilton play in that election?

RC: Hamilton and John Adams were the two leading figures in what was known as the Federalist Party. Hamilton had started out with a lot of respect for Adams as one of the original venerable figures of the Revolution, but their relationship became really pathological.

Adams saw Hamilton as this conceited upstart who had overshadowed him. Hamilton saw Adams as crotchety and temperamental and difficult. So their personal relationship was very bad.

Two things that Adams said about Hamilton—one was that “Hamilton has a superabundance of secretions which he cannot find whores enough to draw off.” And we think the style of political play is rough nowadays.

He also—and this, I think, was far more painful to Hamilton—called him “the Creole bastard,” which was simultaneously sticking it to him in terms of saying he was biracial, which some people imagined he might have been, and also that he was illegitimate. And nothing pained Hamilton more than that.

Hamilton, of course, gave as good as he got. He said of Adams, “I think the man is mad and I shall soon be led to say as wicked as he is mad.”

DR: They were both members of the Federalist Party. Did Hamilton get Adams elected president?

RC: No. Adams ran in 1796. Under the rules of the day, Jefferson was the runner-up and therefore became vice president.

Adams and Hamilton continued to have a very stormy relationship up to the point in 1800 when Adams ran for reelection. Hamilton—again, not one of his finest moments—published an open letter to John Adams. It was really a pretty cruel diatribe about him that, I think, injured Hamilton much more than it injured Adams. But, of course, Jefferson won the election.

DR: Adams was elected to the White House just once. During that period of time, there was in effect a quasi war. We thought the French were going to invade the United States, and Adams asked George Washington to lead an army to repel them. What did Washington say about what he needs to do to pull it off?

RC: Washington was, after forty years of public service, happily retired in Mount Vernon at that point. Adams sent Washington’s name to the Senate before Washington even knew what was happening.

Washington then did something that flabbergasted Adams. He said, “I will only take the job”—which was to lead a provisional army of ten thousand people in case France invaded—“I’ll only take the job if I can have Alexander Hamilton as my inspector general,” which was the number-two job.

By this point Adams loathed Hamilton, and suddenly George Washington, the great political untouchable, is saying, “I’m not going to take this job unless Alexander Hamilton can be my major general,” which is what happened. And that really stuck in Adams’s craw.

DR: Adams ran for reelection in 1800, and he was running, in effect, against Thomas Jefferson, his vice president. What role did Hamilton play in helping Jefferson get elected?

RC: Enormous. However strange it sounds now, under the rules of the time there were not separate elections for president and vice president. Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr were ostensibly on the same ticket—that is, everyone understood that Jefferson was the presidential candidate and Burr was the candidate for vice president. But there was only one election, and they tied.

At that point, Aaron Burr thought, “Well, it might be very nice to be president of the United States instead of vice president.” The vote went to the House, which was still controlled by the Federalists.

And Hamilton did something that Aaron Burr would never forgive and that may have cost Hamilton his life. He advised the Federalists in the House to vote for Jefferson, even though Jefferson had been his bitter enemy. He said, “It’s better to have Jefferson, who has the wrong principles, than Aaron Burr, who has no principles,” which Burr never forgave.

DR: So Jefferson became president and the vice president was Aaron Burr.

RC: Yes. But Jefferson felt that during that period when the election went to the House for a vote, Burr had angled to become president. Even though he was forced to have Burr as vice president for four years, when Jefferson ran for reelection in 1804, he dropped him from the ticket.

Burr then went back to New York—both Hamilton and Burr were from New York—and ran for governor, and Hamilton again blocked Burr in his attempt to win office.

If you were Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton stopped you from becoming president, then stopped you from becoming governor of New York. I think that was really the political context of the duel.

DR: Hamilton was having a conversation with somebody. He said something negative about Aaron Burr, as if he needed to say more than he’d already said. This got put in a letter, and the letter was read by Burr. What happened?

RC: There was an Albany dinner party, and someone reported, in a letter that was published in a newspaper, that Alexander Hamilton had uttered a despicable opinion about Aaron Burr. Historians for two hundred years have been trying to figure out what the despicable opinion was. I came up dry, unfortunately, like all my predecessors.

As strange as it sounds, very often politicians in those days had duels as a way of trying to rehabilitate their careers. So Aaron Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel.

Hamilton’s son had died in a duel, also in New Jersey, about three years earlier. Because of that episode, Hamilton on the one hand had a principled objection to dueling, but on the other hand he felt that, as a political figure and a military man, if he was challenged to a duel and spurned it, he would look like a coward. This would destroy his political and military usefulness.

I think this was more in his head than in other people’s: How could he resolve this conflict? He decided he was going to go to the dueling ground in Weehawken, New Jersey. He would show his bravery by showing up for the duel, but then, when they squared off, he was going to waste his shot.

DR: At the time they often had seconds who would be negotiating to avoid the duel, but the seconds were unable to negotiate a resolution this time. They were in New York. Why did they go across the river to New Jersey?

RC: Dueling, on paper, was illegal in both New York and New Jersey, but it really wasn’t prosecuted vigorously in New Jersey, so duelists would row there across the Hudson—although after Burr killed Hamilton, he was wanted for murder in two states.

In fact, it’s a bizarre story. He was wanted for murder in New York and New Jersey, so where did he flee? He fled to Washington and, because he was still vice president, he presided over the impeachment trial of a Supreme Court justice in the U.S. Senate, even though he was wanted for murder in two states. Strange.

DR: What happened in the duel was that Hamilton put up his gun and shot first but didn’t try to hit Burr?

RC: One of two things could have happened. Hamilton’s second said that Burr fired first. If Burr fired first, what must have happened was that Hamilton, who had the pistol in his hand, as the bullet hit reflexively squeezed the trigger. Because Hamilton’s bullet went about twelve feet high, it hit tree branches above Burr.

If Hamilton fired first, he must have aimed in the air because, again, it went many feet above Burr, and Hamilton had been a soldier, so he was a decent shot. Either way, there is evidence that Hamilton did not aim his pistol at Burr, who may have aimed to kill.

DR: Hamilton didn’t die instantly. They rowed him back to Manhattan. What happened? Everybody came to say good-bye?

RC: It was an extraordinarily dramatic scene. He was rowed back to the Bayard Farm, in what’s now the West Village of Manhattan.

Hamilton was lying in the bed, and he asked his wife, Eliza, to have all of the children line up in a row at the foot of the bed. And he took one last look at them, and then he shut his eyes. It was heartbreaking. We have a lot of descriptions. There were people on their knees weeping and gnashing their teeth. It was an incredible moment.

DR: Is the home that Hamilton built and lived in in his later years in New York still there?

RC: Yes, it’s called the Grange. It’s now in Harlem, or what’s called Hamilton Heights.

DR: After his death, his wife tried, with his family, to perpetuate his image. How much longer did Eliza live?

RC: She lived another fifty years, to the age of ninety-seven. One of the most touching things, for me, about the later years of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton is that she not only did everything in her power to try to honor her husband but Washington as well.

In 1848, she attended the laying of the cornerstone for the Washington Monument. She’d become very close friends with Dolley Madison, even though their husbands had been political opponents. And in the crowd that day with Eliza Hamilton and Dolley Madison was a one-term congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln.

It was an amazing moment. It’s the only moment of that sort I’m aware of where the founding generation touches the Civil War generation.

DR: Can you explain why the ten-dollar bill will not have Hamilton on it?

RC: I can’t. I pray to God that he’ll stay on the ten. I feel it has been his claim to fame. I’d love to see a woman on the currency, but on the twenty. I think maybe it’s a good time for Andrew Jackson to retire. [The Treasury Department ultimately decided to keep Hamilton on the ten-dollar bill; as of spring 2019, Jackson remained on the twenty after the U.S. Treasury Department announced that replacing him with Harriet Tubman would be delayed until at least 2026.]

Hamilton doesn’t have an obelisk near the White House. He doesn’t have a temple on the Tidal Basin. There’s a tiny little statue of him behind the Treasury Department that I think maybe one visitor in a thousand sees.

DR: After Alexander Hamilton, you subsequently wrote a book on George Washington, which won the Pulitzer Prize. In it you say, in effect, that Washington is the indispensable man to the beginning of the country. Where do you think Hamilton stands in that pecking order?

RC: I would also call him an indispensable man. Remember, this is somebody who created the first fiscal system, the first monetary system, the first accounting system, the first tax system, the first central bank, the first mint, on and on and on and on.

He was uniquely qualified to do it, because the first treasury secretary had to be someone with extraordinary financial sophistication. Hamilton had that. It had to be someone who was a great legal scholar and could argue that the Constitution permitted these activities. He also had to be a great enough technocrat to craft these policies, and then he had to be a great enough political theorist to see them as consistent with the American Revolution and the Constitution.

DR: Who is your next book on? What great American are you working on?

RC: Ulysses S. Grant.

DR: And how many more years will that take you?

RC: I’m hoping it will be out in a couple of years. But I’ve been a little distracted by a certain show. [Chernow’s Grant was published by The Penguin Press in 2017.]