5 WALTER ISAACSON on Benjamin Franklin

“The Founders are the greatest team ever fielded. You have somebody of great, high rectitude: George Washington. You have a couple of really brilliant people: Madison, Jefferson. You have very passionate visionaries: Sam Adams, his cousin John. And then you have somebody who can bring them all together: Ben Franklin.”

BOOKS DISCUSSED:

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (Simon & Schuster, 2003)

Kissinger: A Biography (Simon & Schuster, 1992)

Einstein: His Life and Universe (Simon & Schuster, 2007)

Steve Jobs (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution (Simon & Schuster, 2014)

Leonardo da Vinci (Simon & Schuster, 2017)

The phrase “Renaissance man” is not used to describe many individuals today, for there are so few who, in the era of specialization, can do many different intellectually challenging acts in an enviable way. In the modern era, one such man is Walter Isaacson: Rhodes Scholar, member of the Harvard Board of Overseers, former editor of Time magazine, past president of CNN, past president of the Aspen Institute, a member of the Tulane Board of Trustees, the founding chairman of Teach for America, and the author of best-selling books on Henry Kissinger, Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, and Leonardo da Vinci, among others.

One of Isaacson’s books is about America’s first, and perhaps most gifted, Renaissance man—Benjamin Franklin. During his era, Franklin was America’s best-known and most admired person, in the colonies as well as in Europe: publisher, printer, political theorist, humorist, author, scientist, inventor, postmaster, signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and the Treaty of Paris (the only person to sign all three), university founder, library creator, friend of kings and government leaders, the colonies’ overseas representative and negotiator, prominent figure of the day in science and literature and the arts, and, of course, skilled raconteur and well-known lover of life.

Perhaps it takes a Renaissance man to fully understand and write about another Renaissance man. That may account for the insightful, hard-to-put-down biography that Walter Isaacson wrote about Benjamin Franklin.

I have worked with Isaacson on a variety of Aspen Institute matters over the years and have interviewed him in various settings about most of his books. His admiration for Franklin, as well as his appreciation of Franklin’s flaws, comes through in this interview. A reader of it would be hard-pressed to not also read the entire biography. I hope some skilled author will, not long from now, write the biography of Walter Isaacson.

In our conversation, Isaacson first addresses the fascination he has with Renaissance men or “geniuses.” He enjoys trying to understand how the creative mind really works, and what enabled some individuals to think outside of the box so creatively that they could develop theories of relativity, create the iPhone, or discover electricity.

But he notes that even the greatest of geniuses have usually been building on the earlier work of others, and many have had partners to enable them to make their “genius” breakthroughs.

Franklin is in that category. An inventor and a creator of enormous breadth and scope, often he was working with others or building on the work of others. Still, as Isaacson points out in the interview, however Franklin did what he did, the scope of his creations in the sciences, and in so many other areas, made him the country’s best-known individual before the Revolutionary War. He was also the most admired American in Europe, where he lived for nearly two decades, in London and in Paris, representing various colonies and ultimately the new country as it sought to negotiate the end of the war.

Isaacson did note one of Franklin’s secrets: he could spend much of his long life (he lived to the age of eighty-four) without having to work for a living.

Although born poor and educated only for two years, Franklin was able to retire from his successful printing operation in his early forties, having his employees and his common-law wife continue to run the business throughout much of the rest of his life. That provided him with income as well as the freedom to create, think, negotiate, and charm.

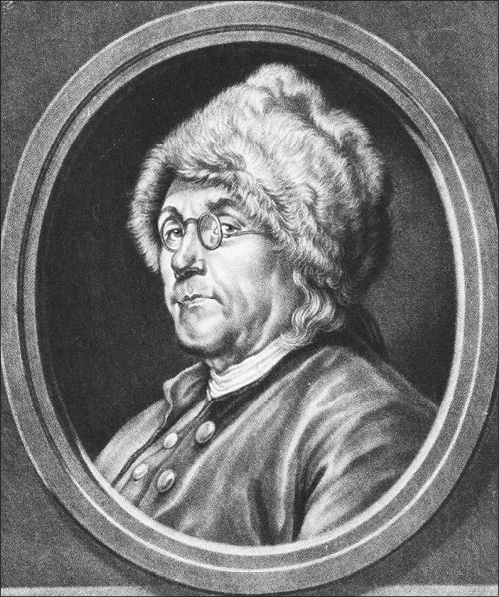

Part of the charm was the homespun wisdom often seen in Poor Richard’s Almanack, an example of an exceedingly popular and profitable Franklin venture. And part of the charm was due to Franklin’s ability to appear as a common man, for instance, not wearing the kind of wig favored by aristocrats to cover their baldness.

His flowing long hair became his trademark. Little could he have imagined how, centuries later, that look would adorn the most commonly printed U.S. paper currency—the hundred-dollar bill.