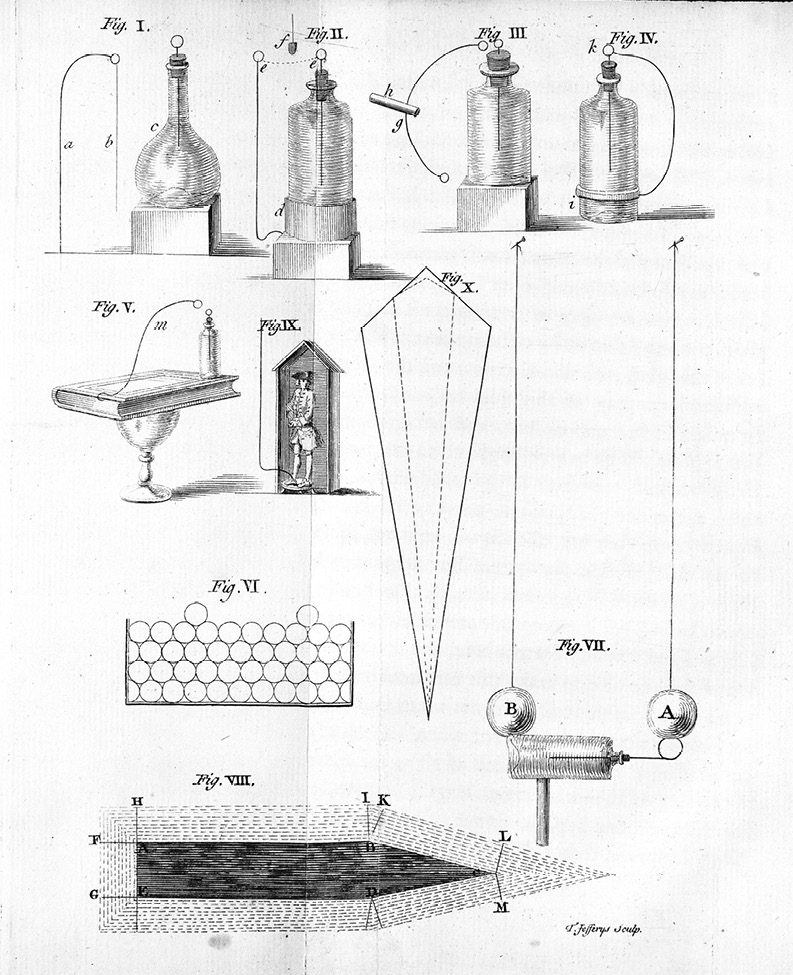

Franklin described his famous electrical experiments in a series of letters that became a highly influential scientific textbook.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): Walter, thank you very much for doing this. Is this one of those rare times that you’re not writing a book?

MR. WALTER ISAACSON (WI): Correct. It’s great to be here at the Library, because you can see the back of Ben Franklin’s head when the sun is coming through the window in the Great Hall, and there’s the bust of him. And let me also say that David Rubenstein has invented patriotic philanthropy, and this is all part of it. So thank you, David.

DR: Thank you very much. Walter, you have tended to write books about people that others would say are more or less brilliant people—Henry Kissinger, Benjamin Franklin, Steve Jobs. Oh, and Albert Einstein. Why did you pick geniuses as kind of a theme? Of those geniuses, who do you think was actually the smartest?

WI: Einstein was the smartest. That one is easy. He was the smartest because he had that quality of genius that allowed him to think out of the box, to be totally imaginative. But he was also somebody who knew what was in the box better than anybody. He was a great physicist.

I like the life of the mind and how the creative mind works. Some people write about great military heroes or sports heroes or literary people. To me, somebody who can think creatively, be imaginative, that’s an interesting thing to wrestle with—somebody like Franklin.

DR: Is it easier to write about a dead genius or a living one?

WI: When I did Henry Kissinger, who of course is a genius, as he will tell you and probably has told you—

DR: A few times.

WI: Right. And he actually was.

He comes up with this whole balance-of-power theory for how to extricate the U.S. from Vietnam and play Russia and China off against each other. But having dealt with him, when the book was over, I got nine letters in one day, hand-delivered by his assistant Paul Bremer, who went on to be viceroy in Iraq. [In 2003–04, Bremer led the Coalition Provisional Authority, which ran the country after the U.S. invasion.]

This was so difficult, in some ways, to deal with that I said, “I’m going to do somebody who’s been dead for two hundred years.” And that’s why I did Franklin.

But there are challenges when you do someone who is in the far past such as Ben Franklin. Let’s take the most ingenious thing he did, which was the kite-flying experiment that led to figuring out the single-fluid theory of electricity. [One popular theory at the time held that electricity was composed of two fluids that worked together to produce a charge.]

Franklin described his famous electrical experiments in a series of letters that became a highly influential scientific textbook.

We have one newspaper article, one letter to Peter Collinson [a Fellow of the Royal Society in London who corresponded with Franklin about electricity], and one textbook written about ten years later that tells you about it. [Franklin’s Experiments and Observations on Electricity, Made at Philadelphia in America, was published in 1751.]

With Steve Jobs, if we were doing the iPad, he would tell me for an hour how he made the curve in the chamfer [the curved edge where the two sides of the computer meet]. So you know a thousand times more from somebody living.

DR: After the Kissinger experience, you wrote about some dead geniuses, Franklin and Einstein. Why did you then pick a person who at the time was living, Steve Jobs? How did that come about, and how difficult was it to write that book?

WI: Partly it came about because I had done the Ben Franklin book, just finished Einstein, and Steve gave me a call. And he said, “Do me next.” My reaction was: “Sure, you arrogant—” Never mind.

I had known him since 1984. We are about the same age, and when he was doing the original Mac computer, he used to come to Time magazine where I worked and show it off. I said, “I’ll do you in twenty or thirty years when you retire.”

But then somebody close to him said, “If you’re going to do Steve, you have to do him now.” I said, “I didn’t realize he had cancer.” And this person said, “He had been keeping it secret. But he called you the day after he was diagnosed.”

So I thought about it. We don’t often write about great business leaders, people who take technology and business and design and art and combine them. We very rarely get up close to somebody like that. We do politicians, presidents. You see them every day. I realized I had an opportunity to get very close to Jobs for two years, at times almost living with him, and to say, “How does a business/technology/engineering/artistic mind work?”

DR: You’ve written a book, The Innovators, which talks about the rise of the Internet and personal computers and so forth. In it, you talk about a lot of geniuses. One you have a fair bit on is Bill Gates. How do you compare Gates to Steve Jobs? Who was smarter?

WI: In the Steve Jobs book I have a chapter on that. They’re both born in 1955. They intertwine often. In the 1970s, when the Apple II comes out, the software writer who does the most for the Apple II is Bill Gates. So they intersected quite a bit. They were the type of friend-rival combination that you see in business.

And they had totally different minds. Bill Gates was smarter than Steve Jobs in a conventional sense. He had more mental-processing power. He could look at two different computer screens with four different flows of information and process things in an analytical-processing-power way that was awesome.

But Steve was more of a genius. Steve had an intuitive imaginative ability to just see around corners, to know what we wanted before we did, and to have a feel for beauty. In the end, Bill Gates creates the Zune. Steve creates the iPod. He’s the creative genius.

DR: In The Innovators, you talk about the history, over several hundred years, of the development of the computer. Is it your view that computers, the Internet, and smartphones came about because of geniuses sitting in their own rooms, or was it because of some other process?

WI: We biographers know deep inside that we distort history a little bit. We make it sound like there’s a guy or a gal who’s a genius sitting in a garage or a garret and they have a lightbulb moment and, boom, innovation happens, an invention is born.

In fact, in the digital age in particular, most people wouldn’t even know—with all due respect to Al Gore—who invented the Internet, who invented the computer or the microchip. The reason is because innovation was done collaboratively.

Bell Labs was a great example. To develop the transistor, they’ve got a quantum theorist like John Bardeen. They have really great physicists like William Shockley. They have deft experimentalists such as Walter Brattain, who knows how to take a piece of silicon and dope the surface of it with boron, so it becomes a semiconductor, and put a paper clip through it and make a transistor based on the theories. You have Claude Shannon—who juggled balls on a unicycle in the Bell Labs corridors—because he’s this great information theorist.

But you also had people with grease under their fingernails who would climb telephone poles and knew how to amplify a signal. It takes a team to put something together. That’s what I wanted to show in The Innovators.

DR: One last question before we get to Benjamin Franklin. How do you actually have time to write these books? You are the president of the Aspen Institute, which is a very active organization. That’s a big day job. When do you write these books?

WI: When I was writing Benjamin Franklin, I was running CNN—which is harder than running the Aspen Institute. But I like to write at night. To me, writing is fun. It’s an escape, because you get to meet people in your mind and do things.

I work from 9 p.m. until 1 or 2 in the morning. Cathy, my wife, is always indulgent. The smart move is that if you’re a night person, you should marry a morning person. Cathy gets up at 6. I like to get up at about 8:30 or 9.

The good thing about the Aspen Institute too is that it’s a think tank. I discovered that nobody ever had a good idea before 9 a.m., so we don’t start that early.

DR: Who will be the next genius you’re going to write about? There are some rumors that you’re thinking about Leonardo.

WI: Leonardo da Vinci is the ultimate genius. You look at his notebooks and realize that everything that I’ve tried to write about, when it comes to creativity, comes from the ability to connect the humanities to the sciences. I know that seems odd—“I’m a humanist. I don’t need the sciences,” and vice versa.

But Ben Franklin flying the kite in the rain, that wasn’t some doddering old dude. He’s a humanist. He knows how to put together humans and science.

The Vitruvian Man, the great drawing by Leonardo da Vinci, is the ultimate symbol of the connection of the sciences to the humanities. So I would love to take on Leonardo, not just as an artist. [Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo da Vinci appeared in 2017.]

When he applies for a job with Ludovico il Moro who in 1494 becomes the Duke of Milan, Leonardo writes a twelve-paragraph letter—eleven paragraphs on “here’s my engineering skills, here’s how I helped build a dome on a church, here’s my military skills, everything else.” And the last paragraph is: “I can paint and sculpt if you need me to as well.” So he does the Mona Lisa while he’s there in Milan, but he considers it all one thing, not like “I’m an artist on one day and an engineer the next.”

DR: Let’s talk about Franklin.

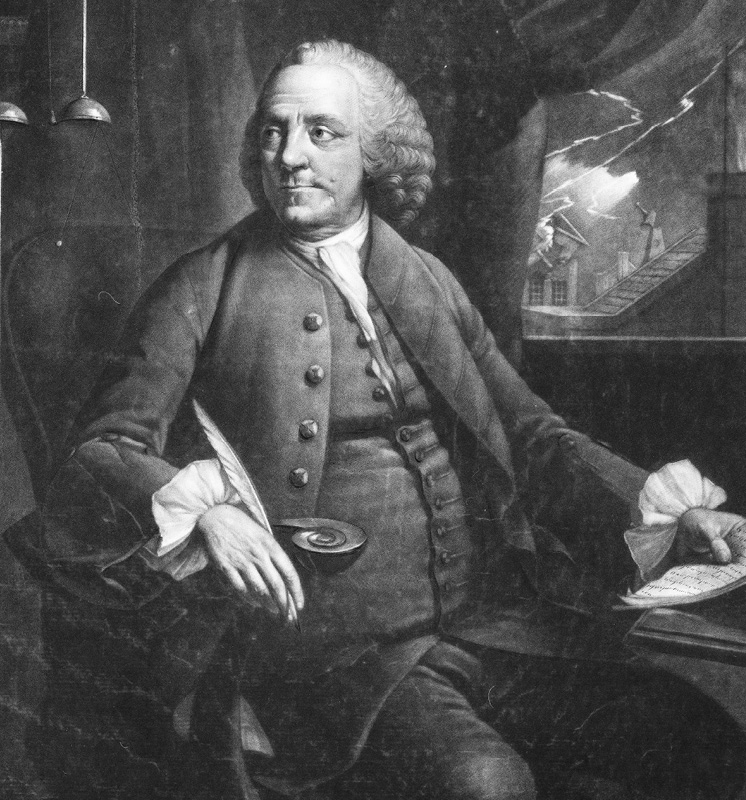

WI: I wrote about Benjamin Franklin at first because I’d done Henry Kissinger, and I realized that the great balance-of-power diplomat we had in our history was Ben Franklin. Most people write about him as a writer, as a newspaper editor who writes wonderful essays. I realized he was a great diplomat.

But then I realized he was also a great scientist. That, to me, was sort of the revelation—that if you’re going to be an Enlightenment thinker, if you’re going to work for the balance of power as a diplomat or the balances that we see in the Constitution, it helps to know Newtonian mechanics, which he loved. That’s what got me very excited about a person who could do science and engineering as well as the humanities and art.

DR: Franklin wasn’t educated to be a scientist. In fact, he only went to school for two years. He was born in Boston, then came to Philadelphia. How did that come about?

WI: Well, he was the tenth son of a Puritan immigrant. As the tenth son, he was going to be his father’s tithe to the Lord. They were going to send him to Harvard to study for the ministry. It was a long time ago, when Harvard knew how to train ministers.

Ben Franklin wasn’t exactly cut out for the cloth. At one point, they’re salting the provisions at his house in Boston, and he was tired of the fact that they had to say grace every night. So he asked his father if he could say grace when they put the provisions away and they could get it done with once and for all for the entire year. His father realizes, “Man, this guy is never going to be a minister,” and doesn’t send him to Harvard.

He gets the next-best education, which is as a newspaper reporter. He’s apprenticed to his brother James. He writes the wonderful Silence Dogood essays—fourteen humorous essays he did for his brother’s paper—about what a waste of money it is to go to Harvard. He says, “Harvard knows only how to turn out dunces and blockheads who can enter a room genteelly, something they could have learned less expensively at dancing school.”

If you were a printer and a newspaper publisher, you were also a bookseller. And so Franklin would take, late at night, all the books from the shelf without his brother knowing it, and he would read Addison and Steele. [Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s witty newspaper the Spectator appeared in 1710–11 and was highly influential in the early eighteenth century.]

Daniel Defoe was one of his favorites, Bunyan’s [The] Pilgrim’s Progress, Cotton Mather’s Essays to Do Good, other things you and I were reading when we were fifteen. He sort of becomes a scientist because Cotton Mather and others were too.

DR: So he’s working for his brother, who is a printer in Boston. And then around age seventeen he decides to run away. He goes to Philadelphia. How does he manage to make himself a living in Philadelphia?

WI: He runs away, arrives in Philadelphia—in the most famous scene in autobiographical literature—with three coins in his pocket. Tips the boatman very generously because he says—here’s something you wouldn’t understand—“When you’re really poor, you’re more generous than when you’re really rich because you don’t want people to think you’re poor.”

DR: I’ve been poor.

WI: Okay, okay. And then he buys the three puffy rolls [another famous scene in Franklin’s Autobiography] and he decides to become a printer. Now, this is really cool. There are about seven newspapers in Philadelphia, a town of three thousand. He says, “I’ll start another newspaper.” These were the good old days for newspapers. He starts a very funny, spunky newspaper, and he’s really good as a media mogul.

Instead of printing the Bible at his printshop and making that one of the books he sells, he says, “People only buy a Bible once a year.” So he invents Poor Richard’s Almanack, so you have to buy it every year.

Then he helps start the colonial postal system because he wanted to make sure that he could sort of franchise his printshops up and down the East Coast, and he would get preferred carriage in the colonial postal system.

DR: So as he’s building this printing business—

WI: And becomes incredibly wealthy.

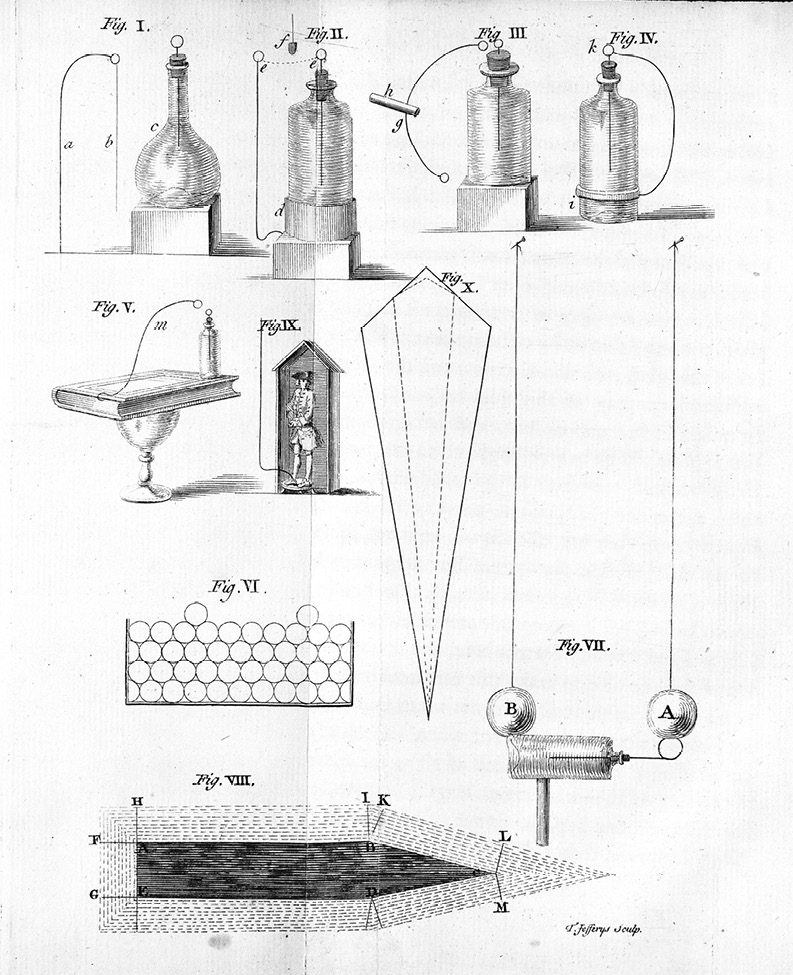

DR: On the side, he experiments with various scientific things. Let’s go through some of the things he supposedly invented. Bifocals?

WI: Absolutely. He was not only a good theorist, he was a good engineer. When he would ride in the carriages on the postal inspection tours he took, he loved to read. Then he would look up and see the scenery, and it was hard for him. He had to switch glasses.

DR: So he did bifocals. What about the famous Franklin stove?

WI: It was actually not as successful as it should have been. One of the problems in that period was smoky stoves and waste of heat. So he invents an enclosed stove that recirculates the air, and he starts making money off of it, but it doesn’t succeed too well, because it was so efficient that the smoke didn’t go up the chimney much and it smoked up houses.

DR: What about electricity? Did he actually discover it?

Among Franklin’s many inventions: bifocals, sketched here in a letter to George Whatley, May 23, 1785.

WI: He comes close. Up until then, electricity was some parlor trick where people would take little balls of amber and put cloth on them and sparks would come out. [Rubbing the amber with the cloth produced static electricity.] People couldn’t figure out what electricity was. So Franklin does the great electricity experiments in the 1740s.

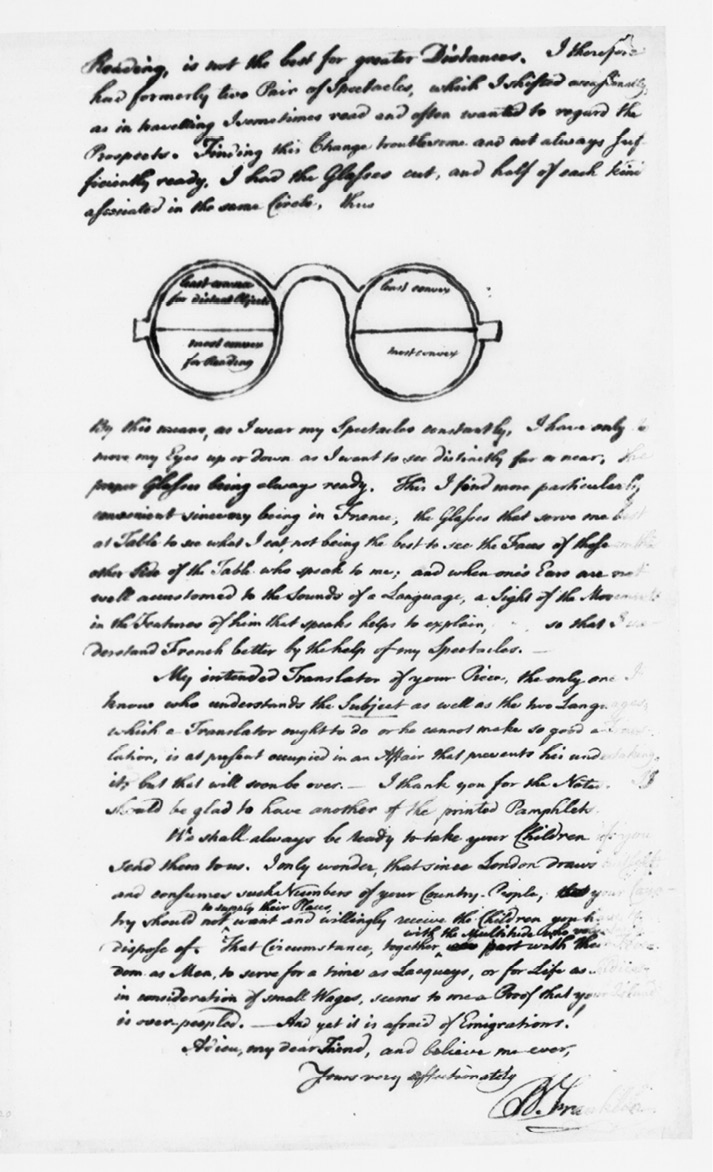

DR: Did he actually go out with a kite, or is that apocryphal?

WI: He did. Totally true.

DR: Isn’t that kind of dangerous?

WI: It was very dangerous. He said one of the great things about the electricity experiments and the kite experiments was that you kept getting shocked and knocked down. He said it was useful because it made a vain man humble. He was always trying to pretend to be more humble.

DR: He discovered that lightning was electricity?

WI: There are three things he discovers that are incredibly important. The first is called the conservation of charge, which even Newton hadn’t discovered. If you read I. Bernard Cohen’s Revolution in Science textbook, this is the most important discovery of that period.

They used to think that electricity was two fluids. Franklin discovered that it’s not two fluids. You’re just taking one charge and another charge and then when you put them back together it’s called the conservation of charge. He even invents terms—positive and negative—and a word, battery, to describe putting Leyden jars together so he can store a charge. [Leyden jars were an early kind of capacitor for storing electrical charges.]

Secondly, he looks at sparks. He’s making sparks. He looks at lightning, and he has a wonderful notebook entry that says: “Here’s the characteristics of a spark [snaps fingers], a quick thing like that, sulfurous smell, whatever. Here are the characteristics of lightning. They’re all the same.”

And at the very bottom he puts: “Let the experiment be made.” So he goes out and flies a kite.

DR: The value of this experiment, among other things, was it led to the lightning rod. Can you explain what that was?

WI: The lightning rod was the most important invention of the eighteenth century. I was stunned, when I researched this book, at the number of lightning strikes that just totally destroyed things.

DR: All over the place. Houses, churches.

WI: All over Europe. One of the great dangers of that period was lightning. They used to consecrate church bells. They used to pray over the church bells and put them in the steeples so that lightning wouldn’t strike there. And they even sometimes stored gunpowder under the steeples. And yet the lightning kept striking the steeples and everything would blow up.

Franklin, in his wry way, in the same notebook with “Let the experiment be made,” writes: “You would think we would try something different after a while.”

He realizes through the kite experiment that lightning is actually an excess of negative charge in the cloud that suddenly discharges to the ground. The kite with its wet string actually brings the charge down, and he captures it with a key and transfers it into a Leyden jar.

By doing that, he realizes that a pointed, grounded, metal rod will capture the excess electrons, or the negative charge of the cloud, and keep it. When he publishes that in the Pennsylvania Gazette, that summer in Philadelphia, forty-two lightning rods go up, and those buildings no longer get hit by lightning.

They actually do the full experiments [that Franklin proposed on electricity] first in France. He does the kite experiment himself, but he hasn’t heard the fact that they’ve done it in France. But he becomes an unbelievably important international celebrity.

DR: He became the most prominent American in the world. He was better known than George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

WI: By far. The French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon has a wonderful epitaph for him—I think it may be on the Houdon bust on display at the Library—which is: “He snatched the scepter from tyrants and lightning from the gods.”

DR: Think about some of the other things he did. He created the first hospital in the United States.

Franklin as scientific investigator: Lightning strikes outside the window as the scientist takes notes during an experiment in this 1763 portrait.

WI: When he was a young newspaper tradesman printer, he started something called the Leather Apron Club, or the Junto. It’s for civic improvement, because he was the ultimate in what you want as a civic leader. He wasn’t looking for big expenditures. He would just get people together and start things.

Every Friday when they met, they said, “What does the town need?” They start, I think, with the Hospital Company of Philadelphia. Then they have a militia, a street-sweeping corps, the Library Company of Philadelphia. On his deathbed, he still has his leather fire bucket from the Union Fire Company [the volunteer fire brigade he helped start], because you’re supposed to sleep with that for safety. Sixty years later, when he’s dying, he still has that.

DR: On the side, he created the university that’s now the University of Pennsylvania.

WI: And you should read the document for it. It’s called Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pennsylvania, and it starts the academy.

It’s a particularly interesting thing because Franklin and Jefferson were really close, but they had separate theories of education. Jefferson believed—and if you read the founding documents of the University of Virginia, you see it—it was to take the best of the best and skim the cream and create what Jefferson calls “a natural aristocracy.”

But Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pennsylvania, which becomes the founding document of what is now the University of Pennsylvania, says this is not just to skim the elite, this is so that every person, whatever their abilities or whatever their station in life, can reach fulfillment by having a better education. I’ll let Jon Meacham come back and defend Jefferson later.

DR: The printing business is a very big business, and so, at the age of forty-two, Franklin says, “I’m done. I’m retired.”

WI: Sort of. He has franchises with all of his apprentices up and down the coast. Something else you would understand—he is getting an equity stake in each one of these but he’s not going to work every day.

DR: He has a deal with his partner where I think he gets half the profits for eighteen years or something like that.

WI: Not bad.

DR: So now he has time for public affairs. How does he get involved in governmental matters? Why did he actually decide to leave Philadelphia and go to London?

WI: He gets appointed. First of all, he hates the proprietors of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. There’s a complex situation there. It was not a Loyalist colony.

DR: The Penn family owned the state, essentially.

WI: Essentially, although Franklin would not have agreed with that. But the Penn family thought they owned it outright.

Franklin’s newspaper was an independent newspaper, but he becomes involved with the Pennsylvania Assembly, which thinks that you should not be able to tax people, as the Penns were trying to do, without the assembly agreeing to it. Franklin becomes the envoy of the Pennsylvania Assembly to London, to be a lobbyist, basically, to get the ministers to agree to allow the colonies to have their own governance. He also then becomes the envoy for Massachusetts and two others.

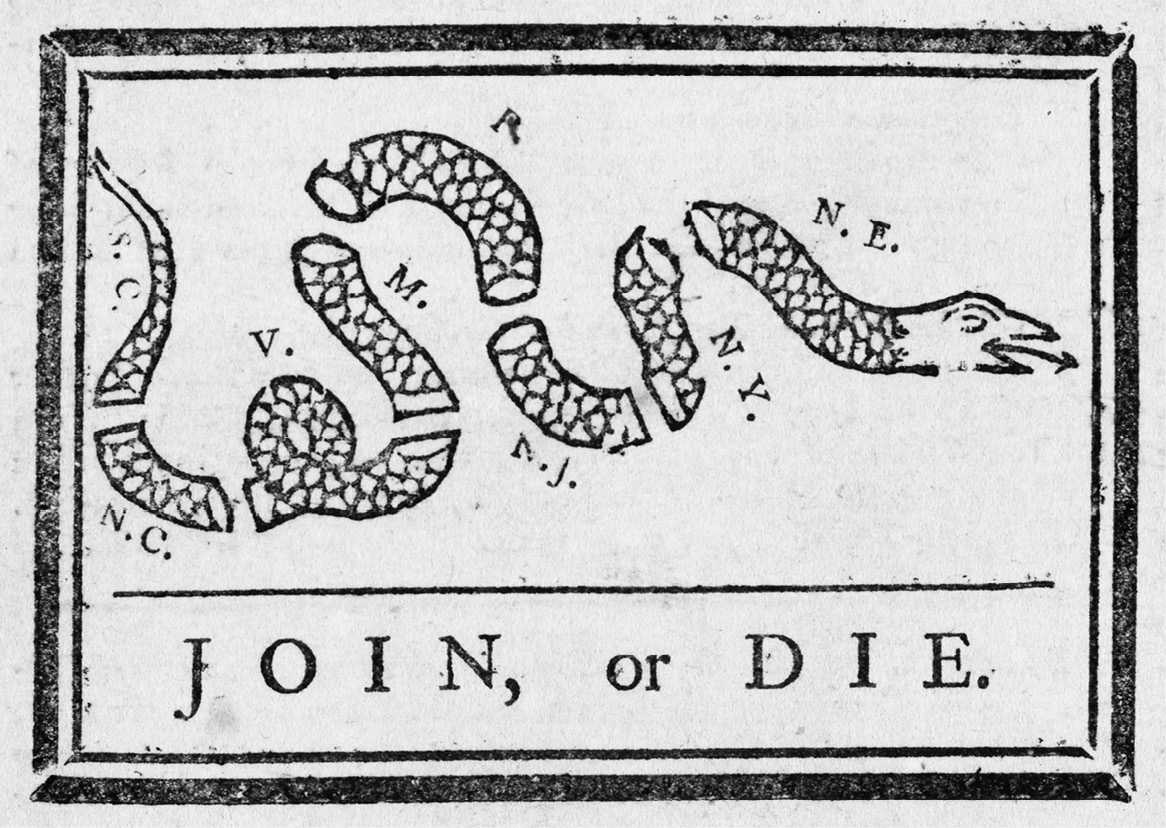

“Join, or Die”: Franklin published this famous early example of editorial cartooning in his Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper to encourage the colonies to band together to defend themselves.

DR: So he eventually moves to London. Does he come right back?

WI: No. It’s kind of odd. He loves it, and he brings his illegitimate son, William, who loves it even more and becomes very aristocratic.

But Ben Franklin is not an aristocrat. He loves “we, the middling people,” so he becomes friends with all the printers and Dr. Johnson and David Hume, the great thinkers of the British Enlightenment. He is already a bit of a celebrity. And, weirdly, he replicates his home life in England, because he has Deborah Franklin as his common-law wife in America. And in London he has Mrs. Margaret Stevenson, who sets up house with him, and he lives with her there.

DR: With his common-law wife, he had two children, a son who dies young—

WI: Frankie.

DR:—and then a daughter, and then he had the illegitimate son with somebody whom we don’t know. And over in London—

WI: He has no children there, but he has a family and basically adopts Polly Stevenson, who is Margaret Stevenson’s daughter.

DR: While he’s over there, he’s trying to make the case that we shouldn’t tax the colonies so much. Then he gets into a problem because the Stamp Act is proposed by Parliament, and Benjamin Franklin is supposed to be against it. [The Stamp Act, passed in 1765, taxed the paper used by the colonists for printed documents and newspapers.] What happens?

WI: This is something everybody in this room can relate to. His great strength, but sometimes his problem, was that he always believed you could find a middle ground and compromise on things.

DR: You can’t do that?

WI: You cannot on the Stamp Act, apparently. He sort of goes along with it and then there’s a blowup in Pennsylvania: “Hey, you were supposed to fight taxation, and look what you’re doing. You’re kowtowing to Parliament.” By having left the colonies and gone to England, he has lost touch with his constituents.

DR: He’s over there for more than a dozen years.

WI: Yeah. And he’s lost touch with the fact that they’re becoming more and more radical. Then he has to get the Stamp Act repealed, which he does.

DR: He gets it repealed, and then people in England say, “You’re going to stay here. You’re one of us now. You’re more of an Englishman than an American.” But then what happens? Why does he become unpopular in England and have to leave?

WI: He becomes more radicalized by the late 1770s, because various ministers for the colonies like Wills Hill, Earl of Hillsborough [later Marquess of Downshire] and others keep imposing taxes from London. [Hill served as secretary of state for the colonies from 1768 to 1772.]

And then he gets involved in a complicated affair I won’t get into, which involves some letters from the royal governor of Massachusetts called the Hutchinson Letters, which he leaks. [Franklin leaked the letters to Samuel Adams, and they were published in the Boston Gazette, creating a political uproar.]

He gets called in front of what’s called the Cockpit in Parliament. Imagine the Senate Foreign Relations Hearing Room but writ large as a battlefield.

He’s called for a hearing and is humiliated. He’s refusing to dress up for the proceedings. He’s wearing this blue frock coat. And he gets so upset that in April of 1775 he sails back to America.

And when he gets home, nobody knows quite if he will declare for independence. Because in 1775, two-thirds of the people in the colonies were in favor of sticking with Britain.

DR: Because he had lived in England so long, did some people in the colonies think he was a spy?

WI: They think he is a spy. They’re not sure which way he’s going to go. Sam and John Adams are like, “Whoa, is he going to be with us or against us?”

The reason it’s complicated is that illegitimate son we talked about, who I said was becoming very aristocratic, does indeed become the Loyalist governor of New Jersey. Franklin is waiting to have a meeting with his son William, and he tells William, “I’m now abandoning the cause of unity and I’m going to become a rebel,” and then makes a big declaration in 1775 that he’s on the side of independence.

DR: He gets elected to the Second Continental Congress, and he’s appointed to a committee to draft the Declaration of Independence.

WI: That’s been one of the times that Congress really created a good committee. It has Jefferson, John Adams, and Franklin on it, along with two others.

DR: Jefferson writes the Declaration, but Franklin is a printer and a writer, so he edits it.

WI: In this building is the coolest document I’ve ever dealt with. It’s the first draft of the Declaration of Independence—Jefferson’s first draft that he submits to Franklin and Adams.

He writes a wonderful letter to Franklin—even though they’re living next door in Philadelphia—saying, “Would the good Dr. Franklin, in all of his wisdom, please look over this draft?” People were nicer to editors back then than when I was an editor. Franklin looks at it, and as you know, there’s that second paragraph, which is awesome.

DR: Jefferson writes, “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable,” and Franklin as an editor says, “ ‘Sacred and undeniable’ is three words. Let’s make it ‘self-evident.’ ”

WI: If you look at the draft, there’s Franklin’s printer’s pen—you know, heavy black printer’s pen that you use to do backslashes. If you’re an old editor like me, you know how to backslash something, which means you’re really taking it out. And he writes “self-evident,” not simply to save words, but because he wanted to show that we were creating a new type of nation based on rationality and reason, not on the dictates of a religion.

He had been friends with David Hume, as I said, when he was in London, and Hume had come up with the notion of “self-evident truths.” But then the sentence goes on, and it says that all men are created equal, and you see what I am pretty sure is and most historians think is John Adams’s insert: “They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.” So in the editing of this document you can see them balancing the role of divine providence and the role of rationality and reason, just in that half sentence.

DR: Jefferson is much younger than Franklin—about thirty-seven years younger. He looks up to him. He takes his edits. When the Declaration of Independence is approved, and we declare independence, what happens to Franklin? Does he remain in Philadelphia?

WI: Well, no. First of all, he gets to help print it, because he’s a printer. They use what we now call Franklin Gothic as the font. It’s a great thing.

But in order to make that document any good, we had to get France in on our side in the war—even back then, France was a bit of a handful—and there’s only one person who can do it. He’s in his seventies. But he is larger than life.

Other than Jerry Lewis, we have never produced somebody that the French were so gaga for. Poor Richard’s Almanack is selling more in France as Les Maximes du Bonhomme Richard Bonhomme Richard is the name of U.S. naval commander John Paul Jones’s ship because Franklin, when he gets there, gets it funded.

They send Franklin over in a wartime journey across an ocean that is controlled by the enemy, meaning British warships. He goes to try to convince France to come in on our side.

He does it in two ways. First of all, he realizes that the American Revolution, with all due respect to us, was not the central act in this play. This was part of a long war between Britain and France that had played out in the French and Indian War and had played out all over Europe, and that, naturally, we should get France in on our side. Like Henry Kissinger, he’s a brilliant balance-of-power diplomat.

Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, is the French foreign minister. Franklin writes these letters that say, “Here’s the balance of power. If you and the Bourbon pact”—meaning France, the Netherlands, and Spain—“come in with us against England, you’ll have navigation rights on the Mississippi.” It is a perfect triangular balance.

But then he does something really cool. He builds a printing press at Passy, his place in Paris, because he realizes you have to win the hearts and minds of the people. It was a battle for public diplomacy. He prints the Declaration and the Virginia Declaration of Rights, all the documents coming out of America, because the notion of liberty, equality, fraternity is welling up in France.

He wins the battle for French opinion. He brings one of these things to the steps of the Académie Française and hands it to Voltaire, who hugs him. There are about twenty thousand people there to watch this great meeting, at which point the French say, “Okay, okay, we’re in on your side.”

DR: So France supports the United States, and we win the war. Does Franklin come back?

WI: He doesn’t come back right away. [Franklin returned from Paris in 1785.]

He has done this remarkable thing of weaving what you would call realism, meaning balance of power and diplomacy, and idealism, which is appealing to the ideals of people around the world. That’s what we still try to do today, but he does it better. So after the war, he negotiates a treaty with England.

DR: By himself or with other people?

WI: He does it with John Adams and John Jay.

A spy who was working for the British, Edward Bancroft, is his valet. Franklin uses that by allowing the British to know that we might still stick with the French if they don’t sign fast.

DR: They sign the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and he stays.

WI: He loves science, and they’re doing balloon experiments and he can’t leave. So he and his grandson are there during the balloon experiments. They’re also all into this new romantic science, like mesmerism [a system of hypnotic induction], created by Franz Mesmer, and the king asks him to test out these things. So he becomes a scientist there for two years before he returns home.

DR: His illegitimate son had an illegitimate son. That’s the grandson you mentioned?

WI: Right. And he and his son are fighting over the affection of Temple, the grandson. When he finally does go home, William, the royal governor of New Jersey and estranged son of Ben Franklin, is now living in England in Portsmouth as a refugee Loyalist who had been traded to England. On the way home, taking Temple with him, the grandson, Franklin stops in Portsmouth, they divvy up the family proceeds, and he and the grandson head off to America.

DR: He comes home, and what he finds in America is that the Articles of Confederation aren’t working so well.

WI: They’re terrible. It’s a mess.

DR: So they have a constitutional convention, and he managed to get invited to that.

WI: He is eighty-one years old in 1787, and so he’s exactly twice as old as the other people—as the average age there—and he becomes the great sage at the Constitutional Convention, the person who pushes this notion of “we can find the common ground here.”

He has a huge impact. The famous speech was the call for prayers, which he does partly because he just thinks it will calm everybody down. But the main thing he does is that the convention, as you know from your high school history, had broken down in that long, hot summer on the big state / little state issue and proportional representation, an equal vote for each state. And it’s unclear whether they’re going to get a constitution.

Franklin gives one of the best speeches, which everybody here should read because you have to deal with this every day. He finally gets up. He’s been pretty quiet.

He’s actually been in favor of a single house—just an elected House of Representatives, not the Senate—but he proposes a full compromise: a House of Representatives to provide proportional representation, direct election, and a Senate that has equal votes for all the states.

He says, “When we were young tradesmen in Philadelphia, we had a joint of wood that didn’t quite fit together. You’d take a little from one side and then shave a little from others until you had a joint that would hold together for centuries. And so too, we here at this convention must each part with some of our demands if we’re going to have a constitution that will hold together.”

And he makes the argument that compromisers may not make great heroes, but they do make great democracies. That’s the essence of how you put things together. Then he asks them to line up by state to sign on to it.

And they do, every state. It was clever, because there were a lot of people against it, but the people who were against it were the ones who wanted voting by state. So, by voting by state, he gets basic unanimity.

DR: So Franklin becomes the only person to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Treaty of Paris, and the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with the French. Is that right?

WI: The four great documents—and the fifth, which he wrote, is the Albany Plan of Union in 1754. It was the first time somebody had proposed that the colonies should unite and form their own government.

DR: When it’s over, he walks out of Independence Hall, and a woman comes up to him and says, “Mr. Franklin, what have you done?”

WI: “What have you wrought in there?” Mrs. Powell says. “What have you given us?” And he says, “A republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

DR: He only lives a few more years after that. He dies at eighty-four. Was he a religious person? Was he a deist? Was he a Christian?

WI: He wrestles with it like we all do. In the book, I talk about each phase of his religious thinking.

For a long while, as a young person, he’s a deist, which is sort of the Enlightenment science view of religion that there’s a Creator who made everything beautiful with all the laws of the universe, but our Creator is not a personal god that you can pray to really hard and the Seahawks will win the Super Bowl or something. God doesn’t intervene. He’s just the great Creator.

Then Franklin says something interesting. He decides that deism is not for him. He said, “Even if it happens to be true, it’s not useful”—meaning it’s more useful to have a more fervent religious received wisdom from God.

That was the interesting thing about Franklin. Almost everything he did, his first question was, “Is it useful?” He said, “I can’t wrestle with all the metaphysical questions of whether God exists or not, but I know what the most useful way is to have a religion.” And so he becomes nondenominational. During his life, he donates to the building fund of each and every church built in Philadelphia.

DR: What was his view on slavery? Was he not a slave owner at one point?

WI: Yeah. And that’s interesting too, of course. He made a lot of errors in his life. He called them “errata,” and he kept a chart of them.

The first error he makes is running away from his brother James when he was apprenticed to him and going to Philadelphia without permission. Then he has a second column in which he says, “How did I make up for it?” The way he makes up for it is that when James is dying, Franklin promises to educate his son. And he does, and puts him in business.

All through his life he does this. But he made one great mistake that he said was larger than them all, which is he compromises on the issue of slavery.

In his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, he had allowed advertising related to slavery [including slaves for sale and runaway alerts]. In fact, one of the ads says, “Inquire at the house of Deborah Read,” meaning his father-in-law’s house. He’d owned two household slaves. He frees them—one of them just leaves—and he frees them in his will. But he realizes he had compromised at the Constitutional Convention.

He said, “Look, we’re going to not be able to solve this in the Constitution until you have the compromise.” That’s the one thing left. And so, at age eighty-one, he becomes president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, because he wants to try to rectify the moral error he had made.

DR: His image is very well known because he had this long hair and kind of a balding head. Was that an affectation?

WI: It was an affectation because he did not want to be pretentious, did not want to put on airs. He said, “We’re trying to create a new type of people who don’t have aristocratic habits.”

DR: No wigs.

WI: No powdered wigs. And we don’t have titles. It’s all going to be common people wearing [working clothes like the printer’s traditional] leather apron, including the blue coat he wears when he’s at the Cockpit, which he puts back on when he signs the Treaty of Paris—as a symbol, this old coat.

But when he goes to Paris for the first time, he’s lived in Philadelphia, London, and Boston. He’s not a wilderness dude. He likes Market Street, not the backwoods.

But he realizes that the French have read Rousseau once too often, and they sort of think of Americans as the natural philosophers prancing around in the wilderness—“the natural man” of Rousseau. [The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) associated virtue with the natural state.]

So when he goes to France, he wears no wig, but he wears a coonskin cap and a backwoods coat that somebody had given him. And in Paris, all the women start doing the coiffeur à la Franklin, which is making your hair look like a coonskin cap. I mean, he was pretty good.

DR: If you look back on the Founding Fathers—let’s say Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin—who do you think actually had the biggest impact on the country at the time, and how would you assess Franklin?

WI: Washington, probably. But let me answer in a slightly different way, which gets back to the innovators.

When I was doing Franklin, I realized it wasn’t about one person. What you do, especially in business, but also in politics, is you build a team.

The Founders are the greatest team ever fielded. You have somebody of great, high rectitude: George Washington. You have a couple of really brilliant people: Madison, Jefferson. You have very passionate visionaries: Sam Adams, his cousin John. And then you have somebody who can bring them all together: Ben Franklin.

If you look at Intel, it’s like having Andy Grove, Bob Noyce, and Gordon Moore, Intel’s cofounders. You have to have a team that holds together. So I would be loath to say who’s the most important, but I think Franklin is indispensable, because there was nobody else in that role.

One of the halls in the U.S. Capitol has beautiful pictures of our history. And one of them is Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, at the Constitutional Convention, under the mulberry tree. He’s got Adams and Hamilton and one other person I can’t remember, and a couple of people are standing around.

He said that under the shade of the tree in his backyard, which is two blocks from Independence Hall, “I can bring people together and the tempers cool down and I can make sure we can get things done.” Sound familiar?

DR: Why do you think that in Washington we have memorials for a lot of great people, but we don’t have any real big memorial for Benjamin Franklin?

WI: Every now and then, you get David McCullough saying, “Sign up to get a John Adams memorial, sign up to get a Franklin memorial.” I think we see Franklin all around us. Wherever I am, I see the fingerprints of Dr. Franklin. It’s like the epitaph on the stone slab in St. Paul’s Cathedral where its architect, Christopher Wren, is buried: “If you seek his monument look around you.”