“Taxis to Hell-and-Back.” Under enemy fire, troops from the U.S. Army’s 1st Infantry Division wade ashore at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944: D-Day.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): 1944 is an extraordinary book, but before we get into it, I wanted to ask you: Why do you pick years for your titles?

MR. JAY WINIK (JW): I could say it’s a good marketing technique and marketing tool. If I have a talent or skill, it’s isolating turning points in time that have been gone over by other people dozens or hundreds of times, and I find something new and different about them and I try to say why those turning points are important.

DR: In my view, there are five key parts of 1944: the rise of Hitler; the Allied response to Hitler; Roosevelt’s health, which was an important issue; the Final Solution; and the American and Western response to the Final Solution. The best thing I’ve ever read about that part of our history is in this book.

Let’s talk about the first part. How did Hitler, a man who was a corporal in World War I—and not particularly brilliant, people would say—manage to rise so high in German politics?

JW: It’s a fascinating question. He was really a ne’er-do-well. He was a failed artist, hawking his sketches to whoever would buy them. He was so down-and-out that he was shoveling snow for money, carrying people’s bags at the train station, and yet this was the man who would come to dominate one of the most cultured states in the entirety of the world.

DR: He didn’t found the Nazi Party, is that correct? He took it over when it was small?

JW: He was sent as an army corporal to monitor this party called the National Socialists, and he didn’t know much about it. [The German Workers’ Party became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, commonly called the Nazi Party, in 1920.] Rather than monitor it and report back to the state, he actually jumped up on the stage and he gave a speech. Somebody who was there, a member of the party at the time, said, “Good God, this man has talent.” And Hitler quickly joined the party. He was party member 555, and the rest is history.

DR: What’s with that mustache?

JW: I think that was his look. The great columnist Walter Lippmann said, when he heard Hitler speak, “We have heard the authentic voice of a great statesman.” Whereas Time magazine compared him to a Charlie Chaplinesque character. Boy, did they get it wrong.

DR: In 1923, Hitler openly tried to take over the government. He staged a takeover in Munich that failed, and he was thrown in jail.

JW: It was almost pathetic. It was called the Beer Hall Putsch.

He went into this beer hall with about twenty compatriots. They fired their pistols in the sky, and about seven of them were killed. Hitler was injured, and he was sent to jail.

Interestingly enough, though, when he was sent to jail for this, he was not your average prisoner. He was actually regarded as a great celebrity. He was given a beautiful room, a nice desk, a lovely view of the yard.

Rudolf Hess, who would go on to infamy and notoriety, became a secretary to Hitler, and it was there in jail that this ne’er-do-well, this celebrity, wrote this book called Mein Kampf.

DR: Where did his virulent anti-Semitism come from? And was there any truth to the story his grandfather was actually Jewish?

JW: It’s one of those questions that we can never fully answer. Suffice it to say that wherever that virulent anti-Semitism came from—and I think part of it came from kicking around in his younger days in Austria, where it really was quite prevalent, and all the ills of the world were blamed on the Jews—well, what Hitler did was he refined it to an art.

DR: He was elected to the German parliament, but how did he actually become the chancellor of Germany in 1933?

JW: At first his party got 2 percent of the vote, and then 12 percent of the vote, and before everybody knew it, it was 33 percent of the vote.

What he did, which was very clever, is Hitler spoke the language of democracy while planning to subvert democracy. Interestingly enough, when he was made chancellor, Goebbels said this was like a fairy tale. A camera actually captured a view of Hitler when he was made chancellor, and they said it was one of pure ecstasy and bliss, the look on his face.

DR: During World War II, what was Hitler’s mental and physical state? He had some physical issues and mental issues. What were the principal problems that he had?

JW: After the Soviet Union entered the war on the side of the Allies and America entered the war, it was clear the war was not going well for Germany. It was also clear to the professional generals, who knew better, that Hitler wouldn’t win.

His physical and mental state sharply deteriorated. His eyes were cloudy. His hands had tremors. He walked with a stoop. He almost certainly had Parkinson’s disease.

He would assemble all his inner circle, a coterie of quacks and yes-men and lackeys, and, of course, his doctor, and he would go into these dull, rambling monologues for hours. But he was really deeply sick. He couldn’t sleep. He was depressed. He took twenty-eight pills a day. It didn’t work.

DR: Let’s talk about the Allied response to Hitler’s rise. In 1938 Hitler gets the Sudetenland, part of what was then Czechoslovakia. Then, on September 1, 1939, he invades Poland. Then he invades the Benelux countries—Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Then he invades France. And then he is on his way to England. What stopped him from actually taking over England? In other words, why did he not just continue the bombing of England and invade?

JW: It’s a fascinating question and an important question in terms of understanding this whole drama. What took place was the Battle of Britain, which was largely fought in the skies. It wreaked a great deal of damage on Britain. But the British people are made of stern stuff, and they fought back.

Of course, they were led by Winston Churchill, who gave that famous speech that “we’ll fight them on the beaches, we’ll fight them in the air.” They were willing to do anything and everything, and it became clear with time that this set of invasion plans, Operation Sea Lion, would not succeed.

It was then that Hitler conceived of this idea—what he thought was his boldest and most brilliant idea, and it proved to be his most prophetic mistake—which was that he would invade the Soviet Union. As he told the generals, “All we have to do is kick the door down and the whole edifice will collapse.” It did not.

DR: Had he not invaded the Soviet Union, with whom Germany had a nonaggression pact, and had he actually tried to invade England, do you think he could have succeeded, given all the military might he had?

JW: It’s not easy to make that cross-channel invasion. We would do it with the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1944, but we were a much larger country with a much larger population base. I’m not so sure he could have subjugated Britain.

DR: Let’s talk about the American response. When the Sudetenland was taken over, when Poland was invaded, when France was invaded, when the Netherlands was invaded, when Belgium was invaded, the Americans said, “We’re not doing anything.” Churchill spent so much time trying to get us to help. Why were we so reluctant to go into the war?

JW: We were still exhausted and worn out from the memories of World War I. The images and the visions of the dead and dying were still very fresh in America.

And there was the America First movement, a movement with Charles Lindbergh as its spokesman. He was trim. He was handsome. He was articulate. And he said, “We must stay out of Europe’s wars.” He made the case for it over and over again. And America didn’t have much of an appetite for intervening.

Roosevelt, interestingly enough, as charismatic as he was, with his fireside chats and with his speeches, you would think he could have gotten the American people to follow him to the edge of the universe. But he was careful never to get too far out ahead of public opinion, and public opinion was not at the point where we were ready to invade or join the fight against the Nazis.

DR: When Pearl Harbor is bombed on December 7, 1941, we declare war against Japan. Would we ever have gone to war in Europe had we not been bombed by the Japanese?

JW: I think we would have gone to war, but much too late in the game. The longer it took, the stronger Hitler got, and as we waited, he took, and as we waited, he took.

DR: Why did Hitler declare war against the United States? The Japanese had bombed us. We didn’t have a fight with him.

JW: As I said, he made two profound mistakes. One was trying to subjugate and take over the Soviet Union, and the other was declaring war on the United States. After Pearl Harbor, he said, “The Japanese haven’t been defeated in a thousand years,” and he was convinced that the Japanese would win again. That was when he made the mistake of declaring war against the United States.

DR: When the United States came into the war, why didn’t the Allies just get all their militaries together and invade France or the Continent from England and do what later became the D-Day invasion? The bombing of Pearl Harbor occurred in 1941. D-Day didn’t occur until June 6, 1944. What were we doing for those three years?

JW: The problem was that we had the seventeenth most powerful military in the world. Wrap your heads around that for a second—not first, not second, not third, but the seventeenth. We were drilling our soldiers with broomsticks. That’s how ill-prepared we were.

And while our generals, including Dwight D. Eisenhower and George Marshall, wanted one great, grand tank battle over the European plains against the Germans, Churchill, who had fresh memories of the disaster with the invasion at Gallipoli [World War I’s Gallipoli Campaign of 1915–16 was a major defeat for the Allies], said to Roosevelt, “You’re simply not ready.”

Roosevelt thought about that and he thought about that, and it was then that he devised, along with Churchill, the North African Campaign. [The Anglo-American invasion of North Africa began with Operation Torch in November 1942; the subsequent military campaigns led to the defeat in 1943 of the German forces in North Africa under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.] That got the American soldiers into the fight, it got America engaged, and it did something very important—it boosted the morale of the American people.

DR: Eventually, after we had a victory in Northern Africa and in Italy, the invasion of France occurred on June 6, 1944. Was it clear from the beginning that the invasion was a success? How dangerous was it? Could we have actually lost on D-Day?

JW: D-Day was a massive effort, but there really was no plan B. In the beginning, the battles went very well on Sword and Juno and the two other beaches in Normandy.

But on Omaha Beach, it was terrible, the pounding the Americans were taking. American soldiers were being cut down, mowed down like wheat. They were bleeding into the water. They had lost many of their senior military men. And it really looked like they could be losing at Omaha.

DR: Suppose the Germans had actually anticipated a Normandy landing. Would we have had a chance of winning then? Because they didn’t anticipate it, is that right?

JW: No, they didn’t anticipate it. They anticipated that the invasion would take place at a place called Pas-de-Calais. [The Allies’ Operation Fortitude involved making the Germans believe this in order to distract them from Normandy.] But I think it was inevitable, given this vast armada of men and machines and battleships, that we would have won eventually.

DR: What about Hitler? Were they afraid to wake him up when it happened?

JW: It’s amazing, if you think about it. The great Erwin Rommel, the famed Desert Fox and one of the best generals of the Nazis—he was off buying shoes for his wife. Meanwhile, Hitler was asleep—he was taking sleeping pills then—and everybody was afraid of waking the Führer. That was so important because they had the panzer tanks ready and waiting. It was the one weapon in the arsenal of the Germans that could have repelled the Americans. But the panzers waited and waited and waited. And Hitler slept.

“Taxis to Hell-and-Back.” Under enemy fire, troops from the U.S. Army’s 1st Infantry Division wade ashore at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944: D-Day.

DR: June 6, 1944, we invade. Finally, we capture France. But the war didn’t end in Europe until April 1945. What was going on for almost a year? The Battle of the Bulge, what was that about?

JW: The thing about Hitler was he was willing to expend his men at almost any cost. He was conducting and overseeing battles with imaginary armies. But his motto also became, for what he saw as his cowardly generals—not a good way of leading his men—he said to his generals, “You must stand and die.”

He conceived of one last-ditch effort, which was the Battle of the Bulge, where he threw everything he could at the Americans. He was hoping that if he could get the Americans to pull out of the war, then he could make a separate peace with the Soviet Union.

DR: Eventually Berlin was being bombed. Virtually every major city in Germany was being bombed by the Americans. Why did the Germans not just say, “Let’s get rid of Hitler”? Why did they put up with this decimation of their country?

JW: Remember that the Germans were a great society. They had great culture. They had great arts. They had great government. They were really just a remarkable state. But something happened under Hitler where the country was in the grips of what I can only say was a form of national psychosis. They stuck with him until the bitter end, even knowing the terrible things he was doing to the Jews, even seeing the concentration camps, the knifing of their own people.

DR: There was an effort to kill him with a bomb. How did he survive that attempt?

JW: There were actually eleven efforts to kill him. But I don’t want that to suggest that there was great mass resistance, because there wasn’t.

Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, an aristocrat in the army, came to despise Hitler. He offered to bring a bomb in a suitcase into the Hitler bunker. It went off, and a lot of people were killed and injured.

But like a cat with nine lives, somehow Hitler survived. And of course he thought this was destiny—that he was fated to win the war after all.

DR: Let’s go to the third subject I wanted to cover, which is Roosevelt’s health. Everyone knows that he contracted polio at Campobello, the island in Passamaquoddy Bay where he spent his childhood summers and that he often visited as an adult. He didn’t really think he had a career in politics after that. He had run as vice president in 1920 on James Cox’s ticket, but he was out of politics. How, as a polio victim, did he get elected governor of New York in 1928 when, in those days, people who had disabilities weren’t treated the way they are today?

JW: He got elected because he had the hubris and the drive to get elected. He believed he was fated for high office. He actually thought that he could become president just like Teddy Roosevelt, his distant cousin, did. And while he couldn’t use his legs, he could use other parts of his body. He could use his arms. There was the famous tilt of his head. He liked to do things that were physical. He liked to drive, to play cards.

DR: How did he drive without the use of his legs?

JW: He had a special car that was made for him. Driving was one of his favorite sports. But he thought he was fated and destined for greatness, and indeed he was.

DR: Why did reporters agree to not photograph him in his wheelchair or being carried? Very frequently he was being carried from his car to someplace else. Why did reporters never photograph that?

JW: It would be unthinkable to have something like this happen today. The press had a gentlemen’s agreement that was rigorously adhered to never to show photos of him in his wheelchair, and never to discuss it in articles. And so he was able to do whatever he wanted.

DR: He ran for reelection in ’36 and won. He ran for reelection in ’40 and won—the first time somebody had served a third term. Then in ’44 he ran again. What was his health like in 1944?

JW: This is what really struck me when I set out to write 1944—his health was disastrous. He had congestive heart failure. He was a dying man. He had chills that wouldn’t quit, a hacking cough that wouldn’t quit.

People would walk into the Oval Office, and the Secret Service was stunned to see that sometimes he had fallen on the ground and was sprawled out. His mouth was hanging open. His eyes were cloudy. He could barely even sign his name on letters.

It was so bad that when he came back from the Tehran Conference [in 1943, when he, Churchill, and Stalin convened to talk wartime strategy], his daughter said, “He has to have a full workup, otherwise there will be hell to pay.”

When he went to Bethesda Naval Hospital for the checkup, he was told that if he didn’t have significant rest, he’d be dead within a year. Those words were prophetic.

DR: In 1944, how did he manage to get the nomination of his party? Didn’t he have to go to the convention and make a speech?

JW: He didn’t make a speech at the convention. This charade continued in which he wasn’t photographed.

By this point, there was talk that something was amiss with him. He would sometimes go in front of the press and he would put on a dog-and-pony show. He would pat himself and they would say, “Mr. President, how are you feeling?” And he would say, “I’m feeling pretty good.” And then Fala, his little dog, would jump up in his lap, and he would say, “I’m a little tired today, a little sleepy, but otherwise all is good.”

And they all fell for it. They loved him.

DR: When he was inaugurated in 1945, was the ceremony held in the Capitol?

JW: Rather than having a full-scale inauguration, they had a small little affair of five thousand people at the White House. Again, his health was really bad. There was a very touching moment where he went out there, it was freezing cold, and his son offered him a cape and he turned it down. He was a gutsy guy.

DR: But subsequent to the inauguration, he did go to Yalta in 1945 for his second big conference with Churchill and Stalin. How did he manage to fly there? He didn’t like flying. Didn’t the planes he traveled on have to fly very low because he couldn’t breathe well above ten thousand feet?

JW: They flew low because that’s what he liked, and because flying was hard for him because of his physical infirmity.

At Yalta, he had this image of two things that drove him. One was that he wanted to see the war to a close, and he needed to make sure Stalin was in the fight to the bitter end. And he wanted to create something called the United Nations. That was his great dream. And so he was willing to do anything to make that happen.

DR: When he gets to Yalta, was he able to really do a good job of representing the United States, given the mental state and physical state he was in?

JW: His mental state, I think, was still fairly sharp—but he was clearly circumscribed by his limited physical abilities and by his ill health. Where this really came into play at Yalta was in the treatment of what to do about Poland. [At Yalta, the leaders left Poland under the control of the Soviet Union, helping set the stage for the Cold War.]

DR: He died how long after Yalta?

JW: A few months later he was dead—April 1945.

DR: Let’s skip for a moment to the question of the Final Solution—the Nazis’ plan to exterminate the Jews. Early in the war, the idea wasn’t to kill all the Jews, it was to get them out of Germany. Why did Hitler and the others decide to kill them instead?

JW: There’s no absolute certainty about why they decided to do that. What happened with the Final Solution is that over time, it evolved. It began with just getting rid of the Jews, putting them in Siberia and relocating them to points east.

Eventually they started these mobile killing squads in the Soviet Union that would line up the Jews, thousands of them at a time, and would just—boom—point-blank shoot them, shoot them, shoot them, and they would fall into a pit. And then, if you can believe it, David, the Nazi doctors were saying, “This is causing problems for the mental health of the German soldiers operating in the Soviet Union.”

That’s when they convened a conference in 1942 at Wannsee [a suburb of Berlin] where all the great heads of the departments of the German Third Reich assembled with sun streaming in through the windows in this beautiful villa, they devised this policy in which they would destroy every living Jew—every man, every woman, every child.

I want to say one other thing about this. After devising this policy of the Final Solution, these extermination camps in Auschwitz and elsewhere, they retired to a beautiful library not unlike this, and they drank brandy and they toasted themselves for a job well done.

DR: Why did they decide to use gassing as part of the Final Solution?

JW: They realized that shooting was inefficient as well as causing these problems for the morale and the health of the German soldiers. They had done some experiments on mentally challenged people in which they used gas, and they realized they could use this.

They refined it to an art form. And it was dastardly.

People would arrive at Birkenau [the killing center that was part of the Auschwitz camp complex], and they would smell this smell like nothing they had ever smelled before. It was broiled flesh. Little did they know that, within an hour, they themselves would be nothing but ashes and dust.

DR: When you arrived at Auschwitz—there were many places like Auschwitz—when you arrived, they took the younger people who could do some work and they would tell them to go one place, and older people, or people who didn’t seem like they could do any work, would be exterminated right away. They were just told to go into the gas chambers? What would the Nazis tell them?

JW: They told them that they would be showered. There was this fiction that they weren’t actually going to kill them.

The Germans were terrified that the Jews would fight back. So, until the bitter end, until the moment that they walked into the gas chambers, they thought they were going for nothing but a shower. Somebody might say, “Oh, I want to be with my child afterward.” And the guards would say, “Okay. Together afterward.” Or somebody might say, “I want to be with my wife afterward.” They would say, “Together afterward.”

DR: They would tell these people, “Take your clothes off, women and men together,” and they would put them in a gas chamber. Death occurred in two or three minutes?

JW: No, no, no. It was a little more horrific than that.

It took about fifteen minutes, seventeen minutes. In the beginning there would be a mass rush for the doors, because people were trying to get away from the gas. And then there would be shouting, and that shouting would become a death rattle, and eventually the death rattle would be a squeak.

Then all two thousand people—let me give you a sense of what two thousand represents: that’s nearly as many men as died during Pickett’s Charge [the failed Confederate military assault that was the turning point of the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War]—everyone would be dead. And then the process would be repeated an hour later.

DR: What did they do with the bodies?

JW: The Germans were nothing if not meticulous. They would shave off the hair and use it for mattresses. They would take out the dental fillings—they would take out the gold. They would take all the victims’ possessions.

Everything was saved. Everything was catalogued in a place that was called Canada, because Canada was deemed a rich country, and everything was to be used and to be disseminated throughout other parts of the Third Reich to help out the German people.

DR: Why were the Germans so obsessed with hiding the bodies? Why were they so obsessed with making sure that the Allies didn’t know that they were doing this?

JW: I think it’s safe to say that there were two reasons. The first reason is that they didn’t want the Jews to fight back. That was reason number one. The second reason is Hitler understood that the German people were willing to follow him in almost everything, but he thought perhaps they were still too cultured to countenance this.

The West was uncertain in the beginning about what was taking place, but as time went on, very quickly there were those in the West who pieced together what was happening.

DR: How many Jews were killed in the gas chambers?

JW: Nobody has an exact figure, but the best figure is six million.

DR: The Germans also exterminated others who were not Jewish.

JW: That’s right. What was unique about the targeting of the Jews is it was a systematic attempt to exterminate an entire race. That’s what separated them [from the Nazis’ other victims].

DR: Did anybody ever escape from Auschwitz?

JW: That’s a great question. It’s worthy of a Hollywood movie. I actually have an agent who’s trying to make one from my book.

There were two men, Rudi Vrba and Fred Wetzler, who were young and healthy, and they weren’t gassed. They were rare people in Auschwitz because they were administrators, and they knew everything that was taking place.

When they saw that there was going to be the worst mass murder in history, the killing of 750,000 to a million Jews from Hungary [and Poland, among other origin countries of Auschwitz’s prisoners], they were determined to tell the truth to the world and especially to Roosevelt. They hid in a woodpile for three days, and they waited to be discovered.

They never were. Eventually while there was darkness, they turned around, they pushed the top of the woodpile open, and they looked toward Auschwitz, and they saw these flames going high into the sky, because the gas chambers were still going.

Then they ran like hell for seventeen days, escaping the SS, escaping German soldiers, escaping anti-Semites. Eventually they got to Slovakia, where they told a few remaining Jewish elders everything that was taking place. They had a photographic memory, these two men, and so there was unimpeachable evidence about what was taking place.

It would eventually wind its way to Washington and land on FDR’s desk. But still nothing was done.

DR: That’s the fifth subject I wanted to cover, the American and Allied response. Once these two men escaped from Auschwitz and people began to know what was actually happening—people weren’t sure what was happening before—when Roosevelt found out, why did he not say, “Let’s do something to prevent this”?

JW: This is one of the great puzzles in history. Roosevelt was considered one of the great humanitarians. He’s the man who uplifted hearts with his fireside chats on the radio, who pulled us out of the Great Depression. And if he was such a great humanitarian, why, in the face of this, would he not want to do something?

Churchill, interestingly enough, when he got word of what was taking place in Auschwitz, he said, “This is the greatest crime in all of human history.” And he told his air force, “Bomb Auschwitz. Use my name. Get everything you can out of it.” Roosevelt did only the minimal amount of what he could do.

DR: Roosevelt had a secretary of the treasury who was a lifelong friend, Henry Morgenthau Jr., who was Jewish. Did Morgenthau lobby Roosevelt on this issue?

JW: For Morgenthau, Roosevelt was his best friend, they had a weekly luncheon meeting, and he owed everything to Roosevelt—for him to take on Roosevelt was not an easy thing. But he was so aghast at the failure of the American Allies to do anything to help out the Jews that eventually he had his department write a thirty-page memo.

This memo had to be the hardest-hitting memo ever given to a president—and not just any president, to the humanitarian Franklin Roosevelt. It was first titled Report [to the Secretary] on This Government’s Acquiescence in the Murder of the Jews. [Written by Morgenthau’s assistant Josiah E. DuBois Jr. and dated January 1944, the report was retitled Personal Report to the President.]

When Roosevelt got this, even though he was sick and ailing and not feeling well, he immediately called Morgenthau into a meeting in the second-floor Oval Office and he said, “What do you want?” It was at that point they set up the War Refugee Board, whose sole intent was to do nothing but save the Jews. But it was too little and way too late.

DR: The Pentagon’s view was that if we divert efforts from the war, it might slow down victory. What was their reasoning?

JW: The man who was running point from the Pentagon was John J. McCloy, one of the great wise men and statesmen of American foreign policy. He came up with reason after reason as to why they couldn’t bomb Auschwitz.

He said that we didn’t have enough planes, when we actually did have enough planes. He said they couldn’t fly that distance, when in fact American planes had been flying around Auschwitz—three, four, or five miles away—for months, as part of the oil war to degrade the Nazi war machine. [Allied planes bombed oil refineries and a synthetic oil plant in the vicinity of the Auschwitz complex.]

Reason after reason was given, and the irony is that, in the end, Auschwitz was bombed, but it was bombed by mistake.

The great humanitarian and now departed conscience of mankind Elie Wiesel was in Auschwitz as a boy at that time, and he said, “We may have feared death, but we did not fear that kind of death.” When they bombed Auschwitz by mistake, the inmates, who could barely stand, barely walk, barely talk, they rose up on their feet and they cheered.

DR: What about the State Department? What was their attitude about doing something?

JW: The State Department mirrored, in many ways, the Pentagon. A man named Breckinridge Long was the head of the visa policy section. At this point, when Jews were cramming American consulates to get visas, because it meant life and death for them, Long sent out a really dastardly memo in which he said to all the consulates, “By various administrative devices, we can postpone and postpone and postpone the giving of visas to the Jews.” He said it not once but three times.

All he had to do was say yes, and two hundred thousand people would have been saved. That’s two Super Bowls’ worth of people. And it never happened.

DR: There was a refugee ship that came and tried to dock in Miami. What happened to that ship?

JW: That was the ship St. Louis. It had a couple hundred Jews on board, and they were escaping Nazi Germany.

They came so close to Miami that they could actually see the shores and the buildings. They had people coming out in little dinghies and little ships waving to them and giving them food. And yet, when they sent a telegram to Roosevelt—“Help us”—all they got was a nonreply. [The St. Louis was forced to return to Europe, where many of its passengers died in the Holocaust.]

DR: When the war was very much near the end, did the Nazis abandon the concentration camps, or did they still try to kill the Jews even though they knew they were going to lose the war?

JW: The very tragic thing, the pathos in all of this, is that even as the war machine was winding down because the Germans were clearly losing the war, the empire of death, the killing of the Jews by any means possible, continued.

The Germans were afraid the Soviets would find out what they did at Auschwitz, so they tried to cover up their crimes as quickly as they could. They took the remaining Jews—there were some fifty thousand of them still in the camps—on a death march during which if anyone strayed, they shot them. If anyone halted, they shot them. And these were the remnants of the Jews. There were six million dead.

DR: When the war was over, the American generals and military went to see the remains of the concentration camps. What was the reaction, for example, of General Patton?

JW: Patton, who had seen more than his share of war and bloodshed, was so horrified by what he saw that he couldn’t walk into the camp itself. From what he did see, he vomited.

DR: What about Eisenhower? What was his reaction?

JW: Eisenhower was infuriated. He mirrored Churchill in thinking this was one of the greatest crimes ever committed.

As one of the troops around him said, “Now, finally, more than anything else, we know what we’ve been fighting for.” Eisenhower made sure that as many people as he could get—he got every congressman he knew to come to Germany and see what happened.

DR: If you had to summarize the main reason the American government didn’t do more to solve the problem—to let refugees in and/or keep them from being exterminated—what would you say?

JW: I think it was the attitude of Franklin Roosevelt, who, despite his humanitarian impulses, was hardheaded and tough-nosed, and he didn’t want anything to compromise the winning of the war. There was never a moment like Abraham Lincoln had with the Emancipation Proclamation.

In Lincoln’s case, he made the war about the Union, about keeping the Union together, until the Battle of Antietam. And then he promulgated the Emancipation Proclamation and made the war a great humanitarian gesture as well. Roosevelt never gave World War II that higher sense of purpose.

DR: Who is the hero of your book 1944—or heroes?

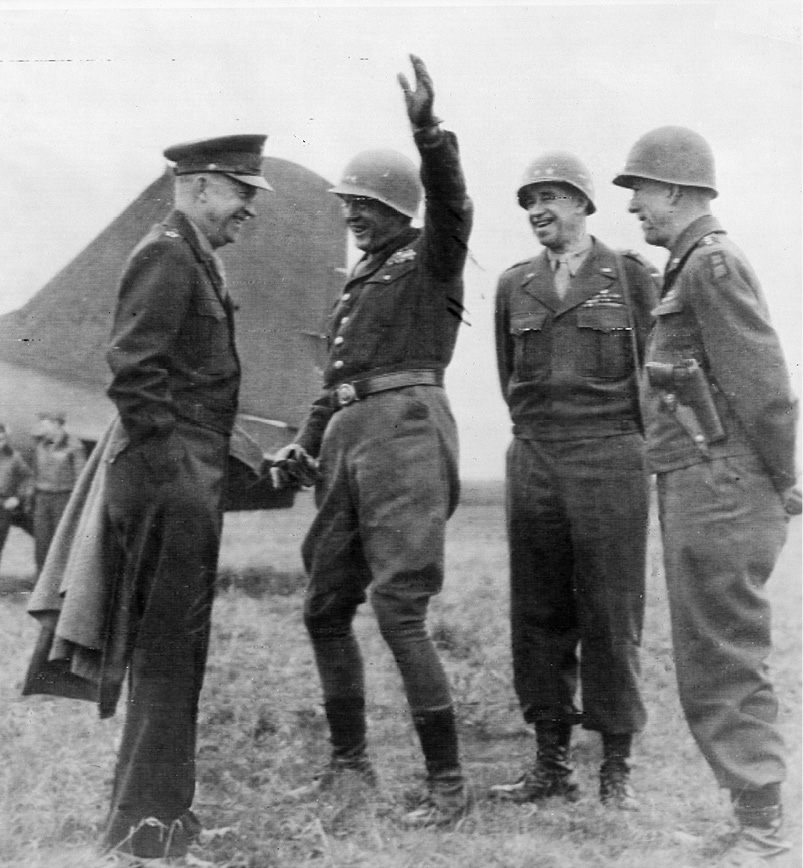

Photographed here during an impromptu meeting at an airfield in Germany with three top Allied generals—George Patton, Omar Bradley, and Courtney Hodges—General Dwight D. Eisenhower was among the military officers appalled by the Nazis’ crimes against humanity.

JW: The heroes are those who escaped from Auschwitz. I certainly think Henry Morgenthau was a hero. There’s a German named Eduard Schulte who was horrified by what was taking place and, at great risk to his own life, he got word out about the Final Solution. There were people who put their lives or their careers on the line, who had a moment where they said, “Enough is enough. We have to do something.”

DR: What was Adolf Eichmann’s role in the Final Solution?

JW: Eichmann was just dastardly. He oversaw the complete extermination of the Jews. Later, of course, he was captured by the Israelis. [Israeli agents caught Eichmann in Argentina in 1960 and brought him to stand trial in Israel, where he was convicted of war crimes and executed in 1962.]

Hannah Arendt talked about the “banality of evil,” and she saw in him a soulless bureaucrat. But I don’t buy that they were soulless bureaucrats who were carrying out the Final Solution. I think they knew what they were doing, and I think they did it with hate in their hearts.