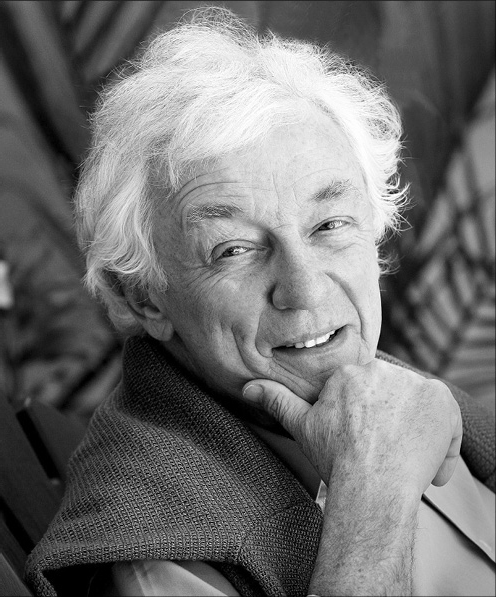

11 RICHARD REEVES on John F. Kennedy

“A great test of a president, it seems to me, is whether he brings out the best or the worst in the American people. Kennedy brought out the best.”

BOOK DISCUSSED:

President Kennedy: Profile of Power (Simon & Schuster, 1993)

I believe that I have read at least one biography of each of our forty-five U.S. presidents, but I think I have read every single biography written about President John F. Kennedy.

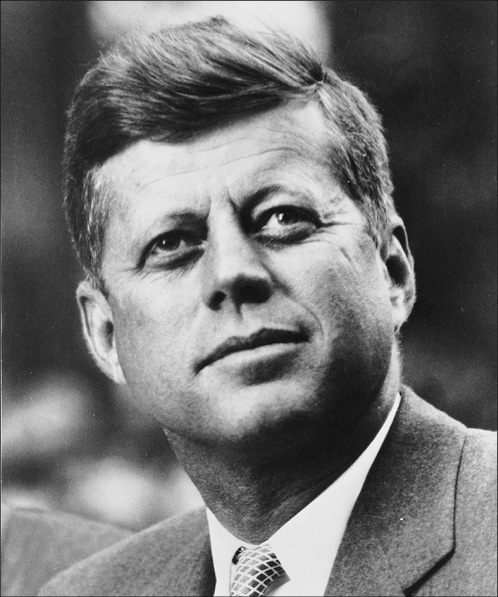

Perhaps that is because he was the president on whom I first focused some real attention. He gave his inaugural address while I was in the sixth grade. My teacher went through that compelling speech with my class, line for line and word for word. I realized that it was truly poetry in prose form, and a call to public service.

The speech inspired my own interest in public service and in becoming a lawyer—which I thought would be a helpful prerequisite to public service—and in also working someday at the White House as an advisor. (To the good fortune of the American people, I never saw myself as a candidate for public office.)

Toward that end of being an advisor, I thought some of the Kennedy eloquence and commitment to public service would rub off on me if I initially practiced law at the firm where Ted Sorensen, Kennedy’s counsel and speechwriter, was a partner. None of the eloquence rubbed off, but my ability to perform public service was no doubt aided by Sorensen’s support, as I moved to Washington to work first in the Senate and then in the White House for President Jimmy Carter.

In recent years, my fond early memories of President Kennedy—and his inaugural address—have remained with me and may account in some ways for my decision to be supportive of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, where I serve as chairman of the board of trustees.

So, what author of a book about President Kennedy would share my deep interest in him and would be best to interview for the Congressional Dialogues series?

Unfortunately, many of President Kennedy’s best-known biographers have passed away, including Sorensen and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., author of A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. However, there remain a number of talented Kennedy biographers.

One of them is Richard Reeves, a well-respected newspaper journalist and biographer. He published his book on President Kennedy in 1993, and thus had the benefit of writing it after information about the White House recordings of the president’s conversations and about his health problems had come into the public domain. (That was not the case with many of the earlier biographies.)

For many in my generation, President Kennedy still holds a fascination, a magical allure that transcends the actual legislative or foreign policy achievements of an administration that lasted less than three years. And that allure—the Camelot factor, perhaps—exists despite the revelations in recent years of the precarious nature of the president’s health and, at times, the incautious nature of his personal behavior.

In Reeves’s view, that allure is due in part to Kennedy’s ability to bring out and to appeal to the best in our human instincts, and in part to the tragic nature of Kennedy’s death as a young man, with so much of his promising future ahead of him. There is no doubt that when charismatic young leaders in any field die young, they tend to be remembered forever as young and vibrant. There will never be pictures of these individuals with gray hair or wrinkles, with physical ailments or in wheelchairs.

Perhaps the perpetual image of a young President Kennedy, sailing or throwing a football or playing with his very young children, is part of his continuing appeal. But Reeves does justice in the interview to Kennedy’s more tangible accomplishments, the most significant of which is the brilliant negotiation that led to the peaceful ending of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Those who lived through that crisis no doubt remember thinking a nuclear war was imminent. (My ninth-grade teacher, I remember vividly, said there was no point in assigning homework that week, for we would not likely be around in a few days.)

Kennedy’s youth, vigor, charm, and tragic assassination are what those in that era most vividly recall about our thirty-fifth president. But they, and future generations, should most remember the skill he used to peacefully end a thirteen-day stalemate with the Soviet Union that had brought the world closer to a nuclear confrontation than it had ever been before.