A bad back left Kennedy in pain much of the time. Here he leaves the hospital with his wife, Jackie, following spinal surgery on December 21, 1954.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): Why is it that, fifty years later, so many people remember President Kennedy’s death—where they were when it happened—and why do we have such a high view of his presidency? He passed not a single major bill as president of the United States. He had the Bay of Pigs invasion, had problems in Laos and Vietnam. Why is President Kennedy still so idealized and so popular?

MR. RICHARD REEVES (RR): He was an athlete dying young, not unlike James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe. That’s why, I think. The whole future was ahead of us, we thought.

A great test of a president, it seems to me, is whether he brings out the best or the worst in the American people. Kennedy brought out the best. That’s part of it.

DR: How long did it take you to write your book?

RR: Ten years. You can do it in five years now with Google.

DR: All right, but it took you ten years. After ten years of research and writing, did you admire him more or less than when you started?

RR: Much more.

DR: Why?

RR: In the first place, I didn’t pick Kennedy because I was a Kennedyphile. Congressman Steve Solarz gave me a copy of a book called The Emperor by the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński. He said, “You should read this. It’s really good.” [Published in 1983, The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat chronicles the final years of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, drawing on accounts by his servants and courtiers.]

What we often do in journalism is study the men near the center of power—in this case, in Addis Ababa rather than Washington. I read The Emperor and admired it greatly. Then I thought, “I could do this about an American president.”

With a president, everything—almost everything—is on paper. There are always witnesses. Meeting or working for the president was the high point of anyone’s life. I thought I could reconstruct Kennedy’s presidency based on that.

Historians write knowing the ending, but I thought I could write it forward as narrative history—write about what Kennedy knew and when he knew it, and what was on his desk when he made decisions.

DR: You never met President Kennedy?

RR: No. I was in school.

DR: If you had the chance to meet him now and you could ask him one or two questions, what would you ask him after having studied him for ten years?

RR: I would ask him first to show me the paper trails to two incidents in his presidency. One was the Berlin Wall, which he knew about in advance and for which he was practically a co-contractor. [Built by the Communist German Democratic Republic with Soviet backing in August 1961, the Wall shut democratic West Berlin off from Communist East Berlin.]

It was a desperate time, really, in human history. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev had a problem. More than two thousand people a day were leaving East Germany through East Berlin, and they were the best. They were the doctors, the lawyers. The elite were running, and Khrushchev had to do something about that.

On the other hand, from Kennedy’s viewpoint, we had fifteen thousand men in Berlin at that time, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers in East Germany and Eastern Europe. If it came to a military action, they could have driven us out of Germany in two weeks and probably out of Europe in a month. The only thing that Kennedy could have done was use nuclear weapons, which was the thing he and other presidents have least wanted to do.

DR: So one thing you’d like to know is whether he in effect consented to the building of the Berlin Wall?

RR: I’d like to see it on paper. I think I showed pretty well that he did, but I never found documents.

DR: What else would you like to ask him?

RR: I wouldn’t ask him about his personal life. We didn’t do that so much in those days.

I’d like to get him to admit that he was behind assassination attempts on Cuban president Fidel Castro and the assassination of Rafael Trujillo. [Trujillo was the dictator who ran the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his death in 1961.]

I’ve done books on three presidents—Ronald Reagan, Richard M. Nixon, and Kennedy—and my conclusion from all of that is the president knew. The president always knows.

DR: But he had deniability.

RR: Right. He’s protected by, in this case, his brother Robert Kennedy. [He served as JFK’s attorney general and close advisor.]

DR: Your book was published in 1993, but many of the books written about President Kennedy were written in the sixties and seventies and eighties. So when you were writing your book, you had the advantage of knowing two things about Kennedy that the world didn’t really know when the other books were written. One was about his health. How ill was he? Did he really have Addison’s disease? Would he have lived through a second term?

RR: He probably would have lived through a second term. He was in pain every day of his life because of his back. He was a very, very sick man.

One of the things that helped me in writing the book was that, if people remember who Max Jacobson was, “Dr. Feelgood”—he supplied the Kennedys with amphetamines and cocaine—he kept a journal, and his wife gave it to me.

In the first place, Kennedy never took a physical to go into the navy. His sense was that you would not be able to succeed in this country if you weren’t part of the war. The Civil War was like that.

All our presidents for decades were Civil War officers. So Kennedy wanted that uniform. His father had friends and enough influence to get his son in the military without a medical.

A bad back left Kennedy in pain much of the time. Here he leaves the hospital with his wife, Jackie, following spinal surgery on December 21, 1954.

DR: He also had Addison’s disease but denied he had it, is that right?

RR: It was denied again and again, including on election eve in 1960.

DR: But the medication for that was cortisone, which made his face and his hair thicker. What other side effects does cortisone have?

RR: Well, it increases your sex drive. You feel pretty good about most things.

Kennedy collapsed in a hotel room in London while he was with Pamela Harriman, then Pamela Churchill. He collapsed. Pamela called her father-in-law, Winston Churchill, and his doctor came to the hotel, the Connaught, and did an examination.

The doctor asked Pamela to come outside. He said, “Your young friend has only a year to live. He has Addison’s.” A fatal disease at that time.

But in Chicago, an American doctor in the public health service—a guy making maybe $25,000 a year—figured out how to make synthetic cortisone. Before that, the only available (and expensive) cortisone came from live sheep. Kennedy’s father had put cortisone in safety deposit boxes around the world.

Three times his son got the last rites of the Catholic Church. One time he was saved while traveling in the Pacific with his brother, because they got the cortisone in time.

It was a terminal disease he had and knew that he had. It is no longer a terminal disease.

DR: The back pain that he often suffered from, to the point that he couldn’t walk, came from the cortisone weakening his bones more than from a war injury?

RR: I don’t think a war injury had anything to do with it at all. It was from birth. The amount of drugs he was taking every day, and the fact that his doctor, Janet Travell, was a total fool, almost killed him.

DR: He had three doctors, in effect, when he was president. He had the navy doctor, who was a regular doctor. He had Janet Travell for his back. And then Dr. Jacobson—Dr. Feelgood—would come down and give him shots.

RR: And would travel with him. He shot him up before the summit in Vienna with Khrushchev.

I want to say something about Travell and what she did. All she was doing was shooting him up with novocaine. So he felt better but his back was getting worse and worse and worse. Ironically, at the time of his death, with exercise replacing novocaine, John Kennedy was probably in the best health of his life.

DR: The other thing that’s come out in the last few years is more information about his personal life. Without going through all the details of it, was he not worried that it would be discovered? And why did the press corps never comment on it?

RR: A lot of people exaggerate now what they knew then. To make a long story short, rich people have long driveways. You don’t know who comes in, who goes out, how long they’re there.

Then there’s the fact that Kennedy was a great generational figure. The symbolism of going from having the supreme commander of the Allied forces, Dwight D. Eisenhower, as president, to a lieutenant in the navy—Kennedy’s first political slogan was “The new generation offers a leader.” The press was part of that new generation. Men related to each other at that time by what they had done in the war.

In those days, men bragged to each other, often without any substance, about what they were doing and whatnot. With the combination of that and the fact that he had hundreds of paid liars working for him, he got away with it.

I had lunch with one of the presidents of the United States who succeeded him. He had read the book. When his wife left the table to go on to greater things, as soon as she left he said, “How did he get away with it?”

DR: He didn’t have a physical, but he served in World War II. His PT-109 boat was split by a collision with a Japanese destroyer. He heroically saved his crew, and they were rescued. He came back and was in the hospital for a while.

His brother Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. was killed in the war. Joseph was more outgoing and was the one many people thought would be running for office. After he was killed, did their father pressure John Kennedy to run?

RR: He did pressure him. But in the end, I think history would have been the same even if he hadn’t. John Kennedy, who always thought he would die young because of all the illnesses he had, lived life as a race against boredom. He was a man who would not wait his turn. He invented the idea of a self-selected presidency because he thought he would be a dead man before he was fifty.

DR: He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1946, the same year as Richard Nixon. Why, after just a few years in the House, did Kennedy think he was qualified to run for the Senate against a Republican incumbent, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., in 1952? Eisenhower was probably going to run for election as the Republican presidential candidate and win that year. Why did Kennedy take that chance?

RR: One of his great friends was Charles Bartlett, who was the Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times. They’d served together in the war. Bartlett said, “Why don’t you wait to run?” Kennedy said, “I can’t wait. They won’t remember me.”

In 1956, in a very short campaign, he tried unsuccessfully to be Adlai Stevenson’s vice-presidential nominee, and he was surprised by how easy it was to get national recognition and credibility. He had always planned to run for vice president first. Janet Travell asked him, “Are you sad about this?” He said, “No. I’ve learned I have to be a complete politician, and I will run from this day to the day I’m elected or die.”

DR: When he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1952, he had a back injury. He was in the hospital awhile to have surgery, and wrote a book called Profiles in Courage then. How did he, when he was in the hospital, manage to write a book that won the Pulitzer Prize?

RR: Well, it didn’t deserve a Pulitzer Prize. It’s really a fairly simple little book. It was his idea and his notes, which then went to Ted Sorensen. [Sorensen was the senator’s chief legislative aide at the time.] Ted did a draft, and then Kennedy, who could write and had been a journalist briefly, edited it. Sorensen rewrote it, Kennedy edited it again. But Ted Sorensen wasn’t the author of that book; John Kennedy was.

DR: In those years he was in the Senate, there was a resolution against Joe McCarthy to condemn him for some of the things he had said and done during his hunt for suspected Communists. Senator Kennedy did not vote for that resolution. Why not?

RR: One, he was in the hospital after his back operation. Two, McCarthy was a friend, particularly of his father’s. Kennedy stayed in the hospital to avoid that vote.

When we talk about Kennedy’s health, by the way, journalism wasn’t as good in those days. Neither was negative research. Anything anyone wanted to know about John Kennedy’s health, including the fact that he had a terminal disease, was in the Journal of the American Medical Association, because he was the first Addisonian ever to survive major surgery.

Because of that, the AMA covered this in depth—although his name was never used. He was referred to as the “thirty-seven-year-old man.” Any journalist today would have figured it out.

DR: So he was in the Senate and didn’t vote against McCarthy. He didn’t actually pass a lot of legislation. Why did he think he was qualified to be president of the United States?

RR: Every president I’ve ever talked to—and I’ve talked to a lot—would point to whoever was in the field at the moment and say, “If they can, why not me?”

DR: He decided to run in 1960. How many primaries did he run?

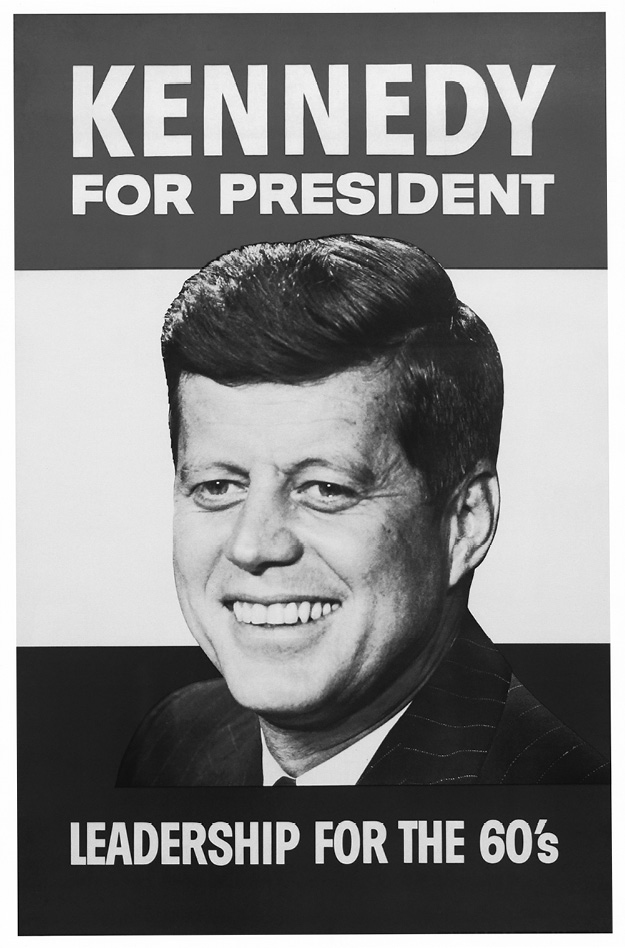

Then senator John F. Kennedy, shown campaigning in Yonkers, decided to seek the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960.

RR: Three.

DR: There were only three primaries?

RR: Right. He totally changed American politics. He was the first self-selected president.

During the four years that Kennedy was never around the Senate, Lyndon Johnson thought he was going to be the Democratic nominee. Kennedy was either campaigning all the time or in the hospital.

But the press had become his constituency, and he had that nomination won before the 1960 convention. He used the primaries as leverage. Again, it was generational. The convention was over before he got there.

DR: The 1960 convention was held in Los Angeles. Johnson went out there and thought he had a chance of getting the nomination, but you say he didn’t really. In the end, he was offered, by John Kennedy, the vice-presidential nomination. Then Robert Kennedy went to take it back. Did John Kennedy authorize that? Why did they offer it to Johnson in the first place?

RR: They offered it because it was the only way they could win. [The Democrats needed the southern money and votes that Johnson, with his deep Texas ties, could deliver.] John Kennedy knew, months before that convention, where he would go with the vice presidency, and so he lied to his brother—a thing he did more than once.

His brother was against it all the time, even at the last moment in Los Angeles, in the hotel, where Bobby went down and tried to talk Johnson into withdrawing. But John Kennedy would not have been president if he had a different vice-presidential candidate.

Youthful, charismatic, and adept at dealing with the press, Kennedy represented a generational shift in American politics.

DR: Now, there had never been presidential debates before the election of 1960. The famous Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858 were actually Senate debates. Why did Nixon agree to have debates in 1960, and how did John Kennedy prepare for those debates?

RR: He had a group of very smart people throwing questions at him, as did Nixon.

As for why Nixon agreed, there are a couple of things we know. One is that the incumbent is always in trouble in a debate.

As Jerry Brown once said to me—I asked him what was the difference between his governorship and his father’s, and he said, “Everyone’s the same size on television. Some housewife in Ventura is just as big as I am on television.” They didn’t know that then.

Nixon thought he could destroy Kennedy in debate, and he thought he could end the campaign right there.

DR: What about the famous makeup issue? Kennedy was asked if he wanted makeup. He said no, and Nixon then said no. But Kennedy already had a tan and had makeup on.

RR: He had pancake makeup. Going back to another point, I want to say one thing about the two of them.

Most of us, if we’re old enough, probably remember the picture of Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, bare-chested, a fatigue cap on, sunglasses, sitting in the cockpit of his PT-109 boat. That was his official picture at that time.

Richard Nixon, who was also a lieutenant in the navy—a supply officer and a senior-grade lieutenant—his campaign picture was standing at attention in dress blues on a beach. And you didn’t have to be Marshall McLuhan to figure out who’s going to win that contest.

DR: The election was held and Kennedy won, with the help of a few friends in certain states, you might say. Who wrote his enormously successful inaugural address, which is only fourteen minutes long? Why was it so special?

RR: It was so special because the country was ready to fall in love. Kennedy had succeeded a much older man, and there was a generational change coming across. He wrote it. Sorensen did drafts.

In the text that Kennedy approved, there was not a single mention of domestic policy. Harris Wofford, a white man who was his civil rights advisor, said, “There are things going on in this country. You’ve got to put something in this speech.” And Kennedy said okay. He added that people are crying for freedom, both abroad—and then the three words “and at home.” Meaning African Americans.

DR: But that was the only reference to domestic policy in the entire speech.

RR: That’s the only reference. We were a Cold War nation, and we thought we were at war. He was a Cold Warrior.

DR: At the beginning of his administration, President Kennedy authorized the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba. [The 1961 invasion involved a group of Cuban exiles who planned to overthrow Fidel Castro’s government, with U.S. backing. The invasion, which took place on April 17, 1961, was a military and diplomatic disaster.] Why did he make such a big mistake?

RR: He was stupid and inexperienced. He believed that Eisenhower had okayed the operation. He later found out that was not true.

The CIA, which did plan the operation, lied to him, and thought that no American president would ever let an American invasion fail. They just assumed the president would call in the marines—that if things went bad on the beaches with these Cuban rich kids, he’d call in the marines.

Well, Kennedy refused to do that. Finally he agreed with the CIA and the air force that he would allow three old B-26 bombers to fly over the beaches of Cuba, so they could evacuate these kids, these invaders, but first the planes were painted over gray. There were no American insignia visible on them.

There also were no Cubans, because the people who planned the raid did not take into account that Cuba is in the Central time zone. The CIA made the whole plan based on Eastern Standard Time, and the planes flew over and nothing happened.

DR: President Kennedy did something that other people like to do today, which is to take responsibility for what happened. When he took responsibility, his poll numbers went up. When he said, “I take responsibility,” did he expect to be more popular?

RR: No. He thought he was finished. He literally said, “Can you believe this? The worse you do, the better they like you.” His approval rate went up into the eighties after the Bay of Pigs.

He was no fool. I actually am not old enough to remember this, but he had this whole series of patriotic meetings, beginning with Eisenhower and Nixon, saying, “We’re with him all the way”—although in private Eisenhower told him he thought he was a goddamn fool. He said, “Did you have anybody in your office who was arguing against this?” Kennedy said no, and Eisenhower said, “Well, you better try next time.”

But there was this great feeling of national redemption with every Republican coming to say, “The president is fine.”

DR: Part of the problem in Cuba was that the Soviet Union was supportive of the Castro regime, so Kennedy really wanted to meet with Khrushchev. He had never met him before. They scheduled a meeting in Vienna in June 1961. What happened at that meeting?

RR: What happened in that meeting tells you more than you want to know about John Kennedy. One, Dr. Jacobson was there, injecting him with amphetamines—speedballs—when he went in.

Second—there are a couple of other politicians who have done this over time—Kennedy’s résumé was faked. It said that he had studied under Harold Laski at the London School of Economics and therefore was an expert on Marxism. [Laski was a famous political theorist, socialist, and Labour Party leader.]

The truth was he enrolled there but never went to England, never met Harold Laski. But all the people around him, who bought into the résumé, thought their president, their boss, was an expert on the Marxist dialectic. He walked into the meeting with Khrushchev, who was an expert in it, and Khrushchev walked all over him.

DR: Kennedy recognized he had been beaten up during the two-day meeting. Khrushchev then felt, “This man I can really take advantage of.” Is that what led to his putting Soviet missiles in Cuba?

RR: It certainly was part of it, although their relationship was a little different by then. Khrushchev’s motivation—Kennedy later said if he were Khrushchev, he would have done exactly the same thing—was that the Soviets did not have any long-range missiles capable of hitting a target in the United States, while we had picket fences of missiles surrounding the Soviet Union and had submarines that could fire missiles that could reach Russia within minutes.

DR: Kennedy had said during the campaign that there was a missile gap. There was no gap, right?

RR: It was a lie. There was a missile gap of a hundred to one in our favor. The Soviets only had sixteen. We had thousands.

Khrushchev had medium-range ballistic missiles. We had long-range, medium-range, and short-range missiles. But if the Soviet leader could get launching sites in Cuba, those medium-range missiles could reach as far north as Washington. It was a gamble. We caught it. I want to repeat that Kennedy said, “If I were Khrushchev, I would do the same thing.”

DR: How did we catch it? Were we surprised that they were getting ready to have the nuclear missiles so close to here?

RR: The Republicans weren’t surprised. Kenneth Keating was not surprised. [Keating, a Republican who served as a senator for New York from 1959 to 1965, suspected the Soviets had nuclear intentions in Cuba.] Keating and other Republicans and the defense intellectuals were saying, “This is really trouble.” And the White House was denying it.

To bring another figure into it, one of the clues that led to Kennedy realizing it was true was that he had a young sometime foreign affairs advisor named Henry Kissinger. Our spying was nowhere near as comprehensive as it is today, and Cuba, during this two-month-long period, was mostly clouded over.

We used the U-2 spy plane to get photographs when the clouds broke, and Kissinger noted that there were new soccer fields in Cuba. The Cubans played baseball. They didn’t play soccer. They do now. They didn’t then. Kissinger, who was a soccer fanatic, said, “There must be Russians there. Russians play soccer.”

DR: Kissinger was then a thirty-seven-year-old consultant to McGeorge Bundy, who was Kennedy’s national security advisor. So they discovered these missile sites. What did they decide to do? The military wanted to go in and invade and bomb? Why did they decide to use a quarantine strategy—a naval blockade—instead?

RR: The military, particularly Curtis LeMay, the U.S. Air Force chief of staff, wanted to destroy the island. And the rest of the world too, if it took that.

It was an interesting thing about Kennedy and the military. He hated LeMay. After one session, in which LeMay talked about eliminating the Soviet Union, he said, “Never let that man near me again.” But six months later, he appointed him chief of staff. His brother said, “How could you do that?” He said, “Look, the man is like Babe Ruth. He’s a bum, but the people love him.”

DR: He also didn’t want him out there saying bad things.

RR: Right.

DR: After they discovered that missiles were in Cuba, they ultimately decided to go for the quarantine approach. Why did Khrushchev send the Soviet ships back and agree to take the missiles out?

RR: Because, from the experience in Vienna—the summit at which he was humiliated—John Kennedy came to understand, as many of his people, say, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, did not understand, that Khrushchev was just another politician in a different system. Kennedy didn’t want to start World War III, and he knew Khrushchev didn’t either.

Then there was a back-and-forth of ghostwritten military memos. It was Bobby actually who suggested, “Ignore this one, answer this one,” and when he answered this one, what came back from Khrushchev was: “We can work this out.” There was a secret codicil, of course, which was that Kennedy—no one knew this at the time—promised we would never invade Cuba.

DR: We also agreed to take our missiles out of Turkey, more or less in a secret deal.

RR: Yeah. But those missiles were worthless anyway.

DR: Let’s talk about civil rights for a moment. When he was running for president, Kennedy famously called Coretta Scott King when her husband, Martin Luther King Jr., was arrested. Why did he make that call, and why was Bobby Kennedy upset about it?

RR: They thought it was a disaster. They didn’t want Kennedy to be seen as the candidate of black people. It was his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, a true liberal, who convinced Kennedy to make that call.

Bobby didn’t know about it. Bobby was furious when he found out about it, because the last thing in the world the Kennedys wanted was to be heroes of the civil rights movement. It was only when George Wallace barred the door at the University of Alabama and it was on national television that Kennedy decided he had to make a stand. [In June 1963, Wallace, then the governor of Alabama, physically stood in the way of African American students attempting to enroll at the segregated state university.]

He asked Wofford, “Why are these black people”—he wasn’t a racist or anything—“why are they doing this? Who are they listening to?” And Wofford said, “They listened to you. You were talking about individual action and freedom.”

It was Wofford and Lyndon Johnson and Johnson’s press secretary, George Reedy, who had been a Communist as a young man, who told him, “You’ve gotten this far in politics by being a northerner. The southerners controlling Congress think you’re only doing this for politics. They think you’re secretly like your father—that you’re secretly on their side.” And the young black activists believed JFK was on their side. Events forced Kennedy to choose.

On the other hand, Kennedy couldn’t get anything done without the southerners. He didn’t want to rile them up. But he then made one of the great speeches in American history—not all of it on paper, working from notes—saying, “This is not a political question. This is not a regional question. This is a moral question. It is a question of what kind of people we are.” One of the great moments in American history.

DR: Why did Kennedy oppose the 1963 March on Washington? He opposed it, and he refused to speak at it.

RR: Absolutely. And his brother had someone stationed in the bowels of the Lincoln Memorial with the switches to turn off the microphones.

DR: If the speeches weren’t appropriate?

RR: Yeah. If they thought they had to do it. What happened next was that Kennedy, who knew a star when he saw one, watched Martin Luther King Jr. deliver the “I Have a Dream” speech on television, and called Bobby and said, “I want him to come to the White House.”

It took King twenty minutes to get there because Kennedy had never allowed his picture to be taken with Martin Luther King Jr. or any black person. Sammy Davis Jr., the black song-and-dance man—and Kennedy friend—was thrown out of the White House because he had a white wife.

In the twenty minutes it took them to get there, Kennedy had a meeting with the National Security Council—these were big days, dense with events—at which he signed off on overthrowing President Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam, which is what, in the end, got us involved there. [Diem was overthrown in a military coup on November 1, 1963, after the United States indicated it would not interfere. That strengthened the position of the Communist North Vietnamese government.]

DR: Let’s get to that right now. Many people associate President Johnson and President Nixon with the Vietnam War, but when Kennedy came into office, we had a few hundred military advisors in Vietnam. When he died, we had about sixteen thousand or so there. Many people who support President Kennedy and like him say that he would have definitely, in a second term, gotten us out of Vietnam. What is your view on that?

RR: My view is he would not have done what Lyndon Johnson did. Diem was a Catholic. That was very important to the Kennedys. It was a minority religion, hated in Vietnam. I have no doubt in my mind that Kennedy would have pursued that war for a while, but nowhere to the extent that Johnson did.

DR: But Kennedy wanted to be reelected, obviously. He began campaigning, and took his wife, Jackie, with him. The first time she went on a political trip with him—the first time she went west of the Mississippi as first lady—was when she went to Texas in November 1963. Why did they need to go to Texas?

Enduring glamor: John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy at their wedding reception, September 12, 1953, in Newport, Rhode Island.

RR: She decided to go. He was going to Texas because the state’s two senators at that time were at each other’s throats. One was a liberal, one was a conservative, both were Democrats. Johnson was supposed to take care of that. There’s money in Texas, and Kennedy wanted that money and wanted the votes. That’s why he went.

It was the first time Jackie agreed to go with him. It wasn’t him saying, “I want you to go with me.” It was her saying, “I want to come with you.” He was dazzled by the way she was received.