Freedom Riders outside a burning bus, May 14, 1961.

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): You spent how many years working on these several thousand pages of books that you wrote on the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King Jr. in particular?

MR. TAYLOR BRANCH (TB): Twenty-four years—1982 to 2006.

DR: Did you ever think maybe you were giving too much time to this project?

TB: No, I was enthralled. It was supposed to take three years, which was two years longer than any other book I had done. But I knew it was a big topic, and the more I got into it—I didn’t want it never to end, but I never regretted how long it took.

DR: How many total pages are the three books?

TB: It depends on whether you count the footnotes. But there are 2,200 pages of book and about 700 pages of notes.

DR: After all of the time you spent on this, what would you like to convey to people about the civil rights movement? Could you summarize, in just one or two sentences, the main point you wanted to convey in these 2,200 pages?

TB: That it was the essence of patriotism. It was modern founders doing what the original Founders had done, confronting systems of hierarchy and oppression and moving toward equal citizenship. And in that sense, I think the civil rights movement is still a shining example of patriotism.

DR: Martin Luther King Jr. is not the only person in the books, but he’s the main person featured. After all your research, what thing or things most surprised you about him?

TB: The surprises begin with his name and never stop. He wasn’t born Martin; he was born Michael. His father went to Germany and saw the birthplace of Martin Luther, and got so carried away with himself that he changed his own name to Martin Luther King and his son’s name to Martin Luther King Jr. This embarrassed his son, who was reluctant to use the new name.

Black men, in those days, didn’t want to use their first names anyway, because it would allow white people to diminish them by being familiar. So he went by M. L. until the end of the Montgomery bus boycott, when Time magazine put him on the cover.

They asked him what his name was, and he said it was M. L. King, and they said, “No, we can’t do that.” Sheepishly, he said he was Martin Luther King Jr. After that, his revised name was public.

DR: Did you come away respecting him and admiring him more or less after you did the research?

TB: Much more after I did the research. At the beginning I was a fellow Southern Baptist who thought maybe he got carried away by turning the other cheek and stumbled into a historic movement. The longer I studied him, the deeper and more profound for me was his understanding of ecumenical, spiritual, and political movements. He was a much more profound figure than I was prepared to believe at the beginning.

DR: If you could have dinner with him tonight and could ask him one or two questions, what would you like to ask the man that you spent twenty-some years researching?

TB: If I had one question, it may not make much sense to most people. To me, the turning point of his career—and a turning point in American history that pushed the civil rights movement into momentum that lasted—was in Birmingham on May 1, 1963, when the movement was about to fail and he was getting run out of town.

He was under tremendous pressure to let children march, and not to let them march, when adults became too afraid or discouraged to demonstrate anymore. It was the biggest crisis of his life so far, and angry black parents came to him and said, “You are absolutely insane. You are not going to skulk out of here leaving our children with criminal records, spoiling what little chance they have to have a decent life.”

He decided to go for broke and to let the children march. On Friday they had 13 adults march, on Saturday they had 600 children march, and on Sunday they had over 1,500 march.

It was “D-Day.” The photographs of dogs and fire hoses turned on young children, I think, melted emotional resistance in the United States to the civil rights movement. It was a turning point.

It’s amazing to me that there’s never been a PhD dissertation analyzing why America turned on the witness of schoolchildren as young as six years old, but it happened, and it was a tremendous risk for him. He had to go in and face those parents and say, “Don’t worry about your children.”

DR: What would you want to ask him?

TB: I would want to ask him, how did he make that decision? How did he decide to let two thousand small children march into Bull Connor’s jail in early May 1963? Because that was a turning point for American history. [Bull Connor was the commissioner for public safety in Birmingham who led the savage attacks on the marchers.]

DR: Your books feature the period from 1954 to 1968—a fourteen-year period of time. Between the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments after the Civil War—when slavery was outlawed, African Americans could be citizens, and they could have the right to vote—between that time and 1954, virtually no progress was made in civil rights for almost a hundred years. Why, in the fourteen-year period you write about, did so much happen when so little had happened in the one hundred years before?

TB: For a lot of those one hundred years, we were busily misremembering everything that had produced the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. We more or less buried them. They didn’t apply the Fifteenth Amendment at all. In retrospect, it’s amazing that you had a Fifteenth Amendment there, guaranteeing the right to vote, but black people couldn’t vote, and nobody seemed to notice.

Even the Fourteenth Amendment—giving equal citizenship and due process to freedmen, that’s what it was for—was nullified within ten years by the Supreme Court. Thereafter, those rights really applied more to corporations than they did to African Americans.

American history can go backwards in race relations, and we were doing that busily. What turned us was in part World War II, in part the Depression, and in part ceaseless agitation that finally confronted, in the 1950s, how we could live up to the ideology that we had extolled when we were fighting Hitler and Japan.

DR: In 1954, we had the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ruling that school segregation was unconstitutional. Was it a shock to the country that the decision went that way and that it was unanimous?

TB: It was absolutely a shock that nine white men would say that the central institution of southern segregation violated the Constitution. Everybody was in shock, including a lot of black people who said, “This is a hallelujah day,” but then in the next breath said, “What’s going to happen to our black schools and our black principals? Are they all going to get fired?”

DR: When the decision came down, the Supreme Court said that with all deliberate speed we should implement this, but things didn’t happen that quickly. Why was it in Little Rock, Arkansas, that there was a confrontation, and did Eisenhower really want to send troops into Little Rock? I thought he was not really in favor of that decision.

TB: He wasn’t so much in favor of the decision. But the more I have studied it, the more I give Eisenhower credit, because once he decided that the honor and the legality of the federal government was at stake in enforcing the court’s orders against open resistance by the state powers, he said, “I want to do this effectively,” and he sent in paratroopers.

He sent in the 101st Airborne. He said, “If I’m going to intervene militarily, I want to do it decisively.” And he did.

DR: Why Little Rock and not some other city?

TB: Little Rock had two things. It had a committed small group of children willing to take upon themselves the burden of being guinea pigs to march into this very large school. They had a lot of support in the local NAACP, and they had a state governor who was very ambitious—not particularly a segregationist, but when push came to shove, he felt that he had to stand up against the federal government and against the power of the courts. He got himself trapped so that he had his state troopers and his National Guard preventing the children from entering.

It was unlike anything since the Civil War. You had the powers of the state resisting the powers of the federal government over the issue of race.

DR: In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to somebody who was white and move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Was that the first time that had ever happened in the South?

TB: No. A large handful of people were arrested for violating the segregation laws for one reason or another. Many of them were not considered suitable to become a test case because the people involved were drunk, or pregnant out of wedlock, or didn’t have an exemplary record.

Rosa Parks was respected by everybody. She was a unique person in that she was a seamstress who spoke perfect English and was the secretary of the NAACP, so that middle-class black folks respected her, and the working-class black folks respected her because she never looked down on them. She had this cross-class admiration, so that when it happened to her, people said, “It happened to Rosa, so we’ve got to stand up for her.”

DR: When she was arrested, there were protests. How did Martin Luther King Jr. get in the middle of this? He was a preacher in that city then, but he was not that heavily involved in civil rights before that, was he?

TB: No. He was fresh out of grad school, and he had just come to Montgomery. He was a brand-new preacher in town, and that’s arguably the reason that he became the leader of the bus boycott. All the established preachers thought it was a ticket to get run out of town, a ticket to certain failure. So they voted him in to head the bus boycott that many felt was going to go down the tubes.

Fortunately, some blessed person recorded the speech he gave on the first night of the bus boycott, December 5, 1955. I spent a week trying to capture the dynamics in his first public address, talking about what the bus boycott meant.

It was full of theology but also full of the Constitution, and what it meant to protest, and why they should protest, and how much discipline it took to protest, and how they were going to make each other proud and stand together.

He was fishing around for an applause line, and finally he said, “There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression.” He went on to the next line, and then all of a sudden in the tape you can hear the thunder of applause come rolling through. He gets the rhythm of that, and you can see the public person being born in that speech.

DR: Did he want to be a preacher? When he was growing up, his father was a preacher in Atlanta. Did Martin Luther King Jr. say, “I want to be like my father”?

TB: No. He said he wanted to be unlike his father, because his father was bombastic and selfish and wanted to drive a big car. King always used to say that in the black South of that era, if you were an idealist you wanted to be a lawyer, and if you wanted to be rich you wanted to be a preacher, which was the reverse of white culture.

So it was a big struggle for him to want to become a preacher. He knew he had been groomed for it and that he loved speaking, but for a long time he wanted to be a lawyer, and it was hard for him to reconcile himself to idealism in the ministry for which he was born.

DR: What was the outcome of the Montgomery bus boycott?

TB: The outcome was that those people who loved Rosa Parks marched for a year and proved that they could do it and made an enormous and inspirational story, but the Supreme Court basically ordered bus segregation to end. It didn’t have that much effect on bus segregation elsewhere. Nothing was ever solved all at once.

But it did become a victory. And it became a victory that the NAACP associated with a legal strategy and winning a court case, and that King associated with people standing up for their rights to make them real, because if you don’t stand up for those rights, it doesn’t matter what the court says.

DR: Not too long after the bus boycott, there was a sit-in at a Woolworth’s counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. What was that about?

TB: That was a spontaneous protest by students who were frustrated that, six years after the Brown decision, not much had changed. Segregation was still there, and the blacks-only and whites-only signs were still everywhere.

The students went and sat down at the whites-only lunch counter and were amazed that they weren’t arrested. So they decided to do it again the next day, and it spread. It spread like wildfire, so that ten weeks later, students from all over the South came to form a student coordinating committee because there were protests going on in so many different places.

Now, King became important then because he was the only adult civil rights leader who instantly said, “This is a breakthrough, because these students have found a way to amplify their words with sacrifice. They’re willing to go to jail. You can’t boycott someplace that won’t let you in.”

King, coincidentally, had been frustrated in the late 1950s because he thought he could preach America out of segregation, like Billy Graham. He traveled hundreds of thousands of miles doing it and failed. He was the first one to say, “This is a breakthrough. My words aren’t enough. I’m a gifted preacher, but if you’re going to be a citizen, you’ve got to be willing to make sacrifices and go beyond just telling everybody what to do.”

DR: There were hundreds of these sit-ins. John Lewis, the future congressman, was involved in one in Nashville, Tennessee. What happened there?

TB: John Lewis is famous for saying, “We’re going to march through the Yellow Pages of Nashville,” because they would march against the theaters, which were segregated, the lunch counters, the hotels, everywhere. Even the airport. They went everywhere that was segregated, and they had a lot of victories.

The message was that every city in the South needed to have sit-ins, because there were no public officials who were openly against the segregation laws. You pretty much couldn’t get elected if you opposed those laws, and so the civil rights protestors marched and marched and marched.

Meanwhile, the people defending segregation mobilized, to the point that King said, in 1962, “The defenders of segregation are mobilizing more rapidly than these isolated movements that I keep getting called to like a fireman for support. We’re losing our moment, our window in history, if we don’t establish a foothold pretty quick.”

That’s why he went to Birmingham and made his supreme gamble there: “We have to make a breakthrough. I have to risk more.”

DR: The segregation that existed in housing and elsewhere—was that only in the South? What about the nation’s capital? What about the North?

TB: There was segregation everywhere. There were segregation laws in the South, but there were segregation policies everywhere. America’s neighborhoods were segregated as a result. We like to tell ourselves that it’s all the result of private decisions, but it’s Federal Housing Administration loans, it’s bank loans, it’s government policy, city after city, in decisions that determine where the highways go, where the public housing is built, and those patterns. We’re still living with decisions that were made at every level of government in every region of the country a long time ago.

DR: King came up with a theory that his supporters should use nonviolent response. Why was that so novel? Where did he get that idea from?

TB: At the beginning, I thought it was from Jesus. After all, that’s what Jesus says: “Turn the other cheek, resist not evil.” The cross is the ultimate symbol of nonviolence.

DR: Was King influenced by Mahatma Gandhi?

TB: He was influenced by Gandhi, but then he went over to India in 1959 to study the Gandhians and came back saying, “They fast all the time. We can never do that in America. Those Indians haven’t eaten barbecue.” Jawaharlal Nehru, the preeminent nonviolent Gandhian, is building nuclear bombs in India, and other Gandhians are fighting over whether they should step on insects, or do this, that, or the other.

He said, “We need our own nonviolence in the United States for black people, because we’re a tiny minority and the only thing we have is our faith and our commitment to democratic principles.” Then he said, “Most Americans think nonviolence is exotic and strange, but American democracy is built on votes, and a vote is nothing but a piece of nonviolence. So if you believe in democracy, you believe in nonviolence, whether you know it or not.”

DR: Was nonviolence a very popular approach at the time?

TB: No. It was not popular. First of all, it was scary, because it meant you’re willing to accept violence.

But King said, after the Freedom Rides of 1961, “If you look at the basis of American democracy after the Revolution, it was self-government—Madison said all our political experiments rest on the capacity of mankind for self-government—and public trust. Without virtue in the people, no form of government can secure liberty.”

King said, “Nobody exemplifies that better than a disciplined Freedom Rider looking at somebody who’s about to hit him in the face, and saying, ‘We may not make a connection, but our children will, because of what we’re doing here today.’ ”

King thought that this kind of nonviolence was the essence of patriotism in the American tradition from the Revolution forward, and that our successes are the advances of nonviolence to make votes count, and that we take them too much for granted and get seduced into measuring democracy by lapses into violence.

DR: At the time all this was going on, King was a rising leader in the African American community. Who were the established leaders? What did they think of him? Did they think he was somebody they didn’t have to pay attention to? At what point did they realize that he was one of them?

TB: Some of them never realized he was. Black critics said they were like crabs in a barrel, some of these leaders—that when there’s not a lot of prestige and money to go around, you squabble over it harder.

Thurgood Marshall called King “a man on a boy’s errand” who didn’t understand the law. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP thought that King was trying to steal his members. Whitney Young Jr. of the National Urban League admired King, but his constituency and business were so different. And James Farmer Jr. thought that King was stealing his thunder in nonviolence, because Farmer was more of an overt Gandhian, whereas King was saying, “I respect Gandhi, but we have to develop our own form of nonviolence.” [Farmer was a main organizer of the Freedom Rides of 1961, in which activists defied segregation on interstate buses.]

So there were a lot of different factions. Then there were these students whom King supported and said had made these breakthroughs, but they resented him later because he got all the publicity. They felt that they were the shock troops and they were always going to jail, but the reporters only wanted to talk to Martin Luther King Jr. And that made some of those students revolt against him.

DR: There was a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Who headed that?

TB: John Lewis headed it for a while. Marion Barry headed it for a while. Stokely Carmichael took it over from John Lewis in the summer of 1966 and instantly launched Black Power. But by that time, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was no longer students, not so nonviolent, didn’t coordinate much, and wasn’t much of a committee. Stokely became kind of a shooting star.

DR: Going back to 1960 and the presidential election that year—King is put in jail in Atlanta. Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon doesn’t call him or call Coretta Scott King, but John F. Kennedy does. Why and how did that call occur, and why was Robert Kennedy upset about it?

TB: Robert Kennedy was upset about it because he thought that the staff aides, Harris Wofford and Sargent Shriver, who tricked Jack Kennedy into making this quick courtesy call from the Chicago airport, had lost the election. The Kennedy campaign was utterly dependent on the solid South of segregationist Democrats. If Kennedy associated himself with a black leader, Democrats feared that Nixon was going to make inroads in the South. So Bobby Kennedy was furious.

Then, typically, he felt guilty about being furious. Kennedy wondered how in the world a court of law could put King on the chain gang, for four months, for not getting his driver’s license transferred from Alabama to Georgia quickly enough. When Kennedy’s aides told him, “Democrats run everything down there, they can do whatever they want,” he felt bad and called the judge. So Robert Kennedy’s education on race went round and round.

But the fact of the matter is that Daddy King [Martin Luther King Sr.] and most of his generation were all Republicans in 1960. This was the party of Lincoln. Black people voted Republican. Democrats had been the party of solid South segregation for a hundred years. It was a different world than the one we live in.

DR: Kennedy wins the election in 1960. Does he say, “I want to propose civil rights legislation right away”?

TB: He said he wanted to change some of the federal laws and regulatory practices that fostered segregation in housing. The FHA would not approve any integration in FHA-supported housing development.

Kennedy promised that he could change that with the stroke of a pen. Two years later, civil rights activists mailed him thousands of pens, saying, “Here’s a pen. Sign.”

It was easy to say he was going to do it, but he was always nervous about what the effect was going to be in the South. He didn’t think he could get reelected if he lost any more southern states.

DR: The March on Washington occurred in August of 1963. Why did John Kennedy not speak at it? Was it controversial to have the march? What was the big fear about it?

TB: The march occurred after those kids that I mentioned marched in Birmingham in May of ’63. Because that event broke emotional resistance, demonstrations spread. There were seven hundred demonstrations in a hundred-something cities within the next few weeks. It was that firestorm that made King call a march on Washington.

Kennedy was not ready to introduce legislation, and the standing presumption was that a black march for freedom in the nation’s capital in 1963 would inevitably produce a bloodbath. The Pentagon stationed paratroopers all around Washington. Public employees were sent home. The city canceled liquor sales. Hospitals stockpiled plasma. Major League Baseball canceled two Washington Senators baseball games, the day of the march and also the day after, in advance, because they assumed we would be cleaning up from violent disorder.

So it was a terrifying event. No aide would recommend that the president go to such an event if that’s what people were expecting.

One reason that it has such a sunny reputation now, the March on Washington—“ ‘I have a dream,’ this is nice, who could be against that?”—was the stark relief from what people publicly expected.

DR: King was the final major speaker there. Why was he last?

TB: Nobody wanted to go after him. With good reason.

He was a really accomplished speaker. He was great at reading an audience, a skill he used at the march, because the famous parts of his speech were extemporaneous. They weren’t what he wrote. He went off on a riff like a good jazz musician, which is what Baptist preachers were.

A lot of people think that he stayed up all night and wrote a really great speech, but he discarded his written text in the middle of delivering it and went off on two or three of his familiar riffs: “With this faith.” “Let freedom ring.” “I have a dream.”

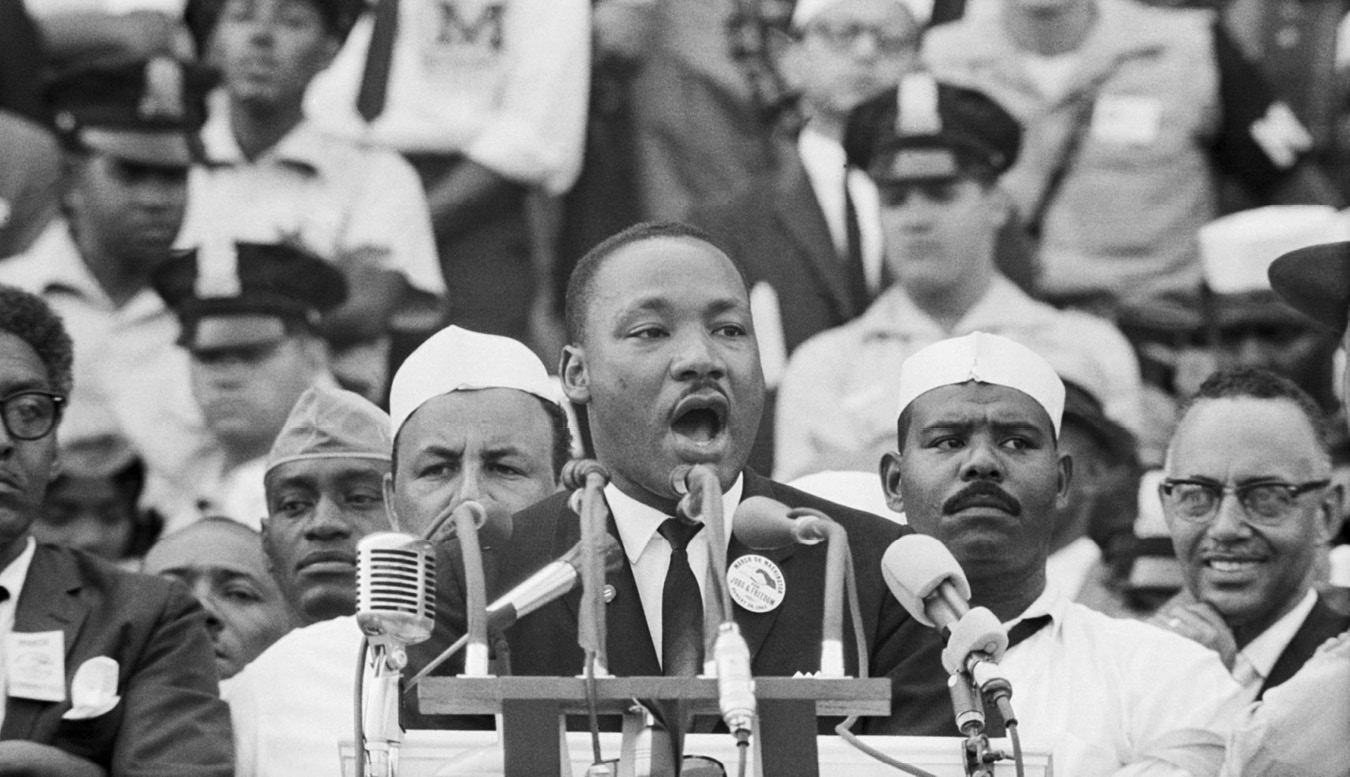

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington, August 28, 1963.

DR: That speech was one that he had given before. White people had not heard it, but many black people who were there had heard it before, is that right?

TB: Black people in the audience probably hadn’t heard it, but those who traveled with him had heard it. Crowds had heard it in Chicago and Detroit not that long before, or at least themes from it. Riffs—we call them riffs.

DR: After the march, the leaders went to the White House. What did President Kennedy say to Dr. King?

TB: He said, “I have a dream.” Kennedy recognized a good line. He kind of teased him.

DR: Did the speech instantly become famous? Did it make the front page of the New York Times and the Washington Post the next day?

TB: The press reaction mostly was astonishment that there wasn’t any bloodbath. The Washington Post didn’t have many stories at all. The New York Times had seven stories on the front page about what a phenomenon the march was, but it didn’t isolate the speech initially as a great thing, in part because it was so late, they probably had their deadlines coming up and wrote other stuff.

DR: J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, didn’t seem to like King. How did he persuade President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy to let him wiretap him?

TB: That is still a historical conundrum. I wish more historians were writing about it.

Hoover asked Bobby Kennedy to wiretap King in the summer of ’63, right after Birmingham, when all the demonstrations were going on. Kennedy turned him down. After that, King gave the “I Have a Dream” speech and the administration submitted its civil rights bill, with King as a prime supporter, so they kind of married each other in politics. Yet Kennedy approved the wiretap afterwards, in the fall of 1963. He was under tremendous pressure.

It’s one of the great wrestling matches in American history, why he approved that. Bobby Kennedy knew he was handing his rear end to J. Edgar Hoover by putting his signature on that document. Hoover would have that secret over him for the rest of his life.

DR: Did John Kennedy get the results of the wiretaps? Did he ever talk to King about it?

TB: He didn’t talk to King about the wiretaps. He wouldn’t have disclosed that he had them.

But even before the wiretaps, Kennedy felt so exposed politically when he had to submit that civil rights bill in the summer of ’63 after Birmingham and all those demonstrations. JFK said, “We can’t fight all these fires one by one. We’ve got to put a bill out there to stop them.”

He had King to the White House in June of 1963 because he felt that he needed to control him. He took him out into the Rose Garden for privacy, astonishing King.

In seemed to King that President Kennedy thought Hoover was bugging the Oval Office. Kennedy took him outside to escape it and whispered, “They’re after you. If they shoot you down, they’ll shoot me down too. We have to be really careful. You’ve got to get rid of some of your supporters because they’re Communists.”

Kennedy named some, and King said he was astonished. He kept saying, “What’s the evidence? I love these people. They’re volunteers. They don’t work for me.” He said, “I don’t believe in shunning people.”

They went round and round. King went home and put this case before his aides, Harry Belafonte, and a bunch of others. Some of them said, “This is how a witch hunt starts.” Some of them said, “Is this the price of the civil rights bill?” It’s that kind of politics going on behind the scenes.

DR: Kennedy is assassinated a few months later, in November of ’63. Lyndon Johnson becomes president. He pushes Kennedy’s legislation through. Why did a southern senator, a senator from Texas, who had been so close to the segregationists in the Senate, push civil rights legislation, and how did he get that through?

TB: For one thing, the death of President Kennedy had a cathartic effect on the whole country. People thought hatred and division had something to do with it, and the civil rights bill was about addressing and trying to overcome hatred, so that helped.

But Johnson doesn’t get enough credit for his inner drive, and what he really wanted to do as president, and where he came from in life. To me, the biggest proof of that is that within a month of passing the Voting Rights Act, he passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of ’65, which opened legal immigration to the whole world that had been previously excluded.

He said, “Never again will freedom’s gate be shadowed by the twin barriers of prejudice and privilege.” I think he was speaking from his heart there, and he risked a lot for the civil rights legislation.

DR: The Voting Rights Act came about in part, I assume, because of the 1965 marches in Selma and other places. Can you describe what the Selma march was about and why voting rights had not really spread to the South? How many black voters were there in some of the southern states and southern congressional districts?

TB: Practically none. The march from Selma to Montgomery went through Lowndes County. No black person was known to have tried to register to vote there in the entire twentieth century into 1965, even though Lowndes County was 70 percent black. It was almost medieval.

The Fifteenth Amendment said everybody should have the right to vote, that it should not be abridged on account of race, but we had turned a blind eye to that for a century. It took these marches to wake people up to that fact. In a way, this was the crescendo of a movement that had been building for a long time.

The events of Bloody Sunday—March 7, 1965, when the marchers were attacked, those famous pictures of John Lewis being beaten on the bridge—occurred on a Sunday morning, and it was not until that night that footage of it made television. In those days you had to take your film, run to an airport, get on a prop plane, fly to New York, get the film developed, take it in, and figure out how to put it on the air. It went on that night.

King sent out a telegram that same night, Sunday night, saying to all of his contacts in the church mostly, “Come to Selma.” He didn’t say, “Discuss this at your next meeting,” or “Vote for a new candidate,” or “Ask Congress to do something.” He said, “Please come to Selma to march with me on Tuesday from the same spot where these people were beaten.”

On Tuesday, there were a thousand people—nuns and priests and everybody, from all over the country—who figured out, before Expedia, how to get there in less than thirty-six hours. It was a stunning mobilization.

DR: During the march, he gets to the end of the bridge and the troopers say, “Go ahead.” Why did he turn around?

TB: That’s one of the great studies in politics. The federal court had ordered him not to march until they could hold a hearing on whose fault it was that there had been beatings in the first place. John Doar, an assistant attorney general trusted by the civil rights leaders, went down and told Dr. King, “You’ve never defied the federal courts. You can’t afford to do it now because it’ll throw us against you.”

King was negotiating at the same time with members of Congress about whether they would introduce a voting rights bill. He’s secretly negotiating also with Alabama governor George Wallace’s people about what they’re going to do, thinking that they may be laying a trap by asking him to march and defy the federal court order and then get out into Lowndes County where the Ku Klux Klan is very strong. Nobody thought they would march more than five miles.

He was battered by some people saying, “This is a breakthrough. We can march right through there. You’re a coward if you don’t march,” and by other people saying, “You’re a fool if you do.” It was a very, very critical moment.

In that moment, Dr. King decided to put his faith in the promise of the federal government to deliver a voting rights act. He said, “We are half-marching. We’re keeping the movement going, but we’re turning around. Let’s go back to the church. We’re not willing to defy this federal order.”

As Johnson later told him, “It’s the best thing that ever happened in American history. You mobilized that public opinion that allowed me to go before the joint session of Congress and propose the voting rights bill. That’s the way it’s supposed to work: active citizens and responsive government.”

DR: King won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Was he surprised? And was it controversial in the United States at the time that he won?

TB: It was controversial to J. Edgar Hoover, who said that he was the most notorious liar in the country, and that they really had to drag the bottom of the barrel for that prize.

But of course, Hoover was a unique person. He thought that he should get the Nobel Peace Prize.

It was a surprise, but it went over pretty well. It marked a turning point for King, because he had been trying to build the influence of his movement. He gets to a pinnacle in Oslo, and Andy Young says, “We’re going to celebrate this for ten years. We’ve finally gotten an antisegregation bill through, and you’ve got the Nobel Prize.”

King says, “No. We’re going to Selma. Not next year but next week.” And within a month he’s in jail in Selma.

He had been very reluctant to take personal risk. He resisted being in the sit-ins of 1960. He didn’t go on the Freedom Rides in 1961. He resisted the kind of sacrifice that the students were making. But from the Nobel Prize on, he dragged his staff to Selma, then he dragged them north, saying, “We have to prove that the race issue is not now and never has been purely a southern issue.”

DR: He said, “I care about poverty as well as racism, and there’s poverty in the North,” and he went to Chicago. Why did he pick Chicago?

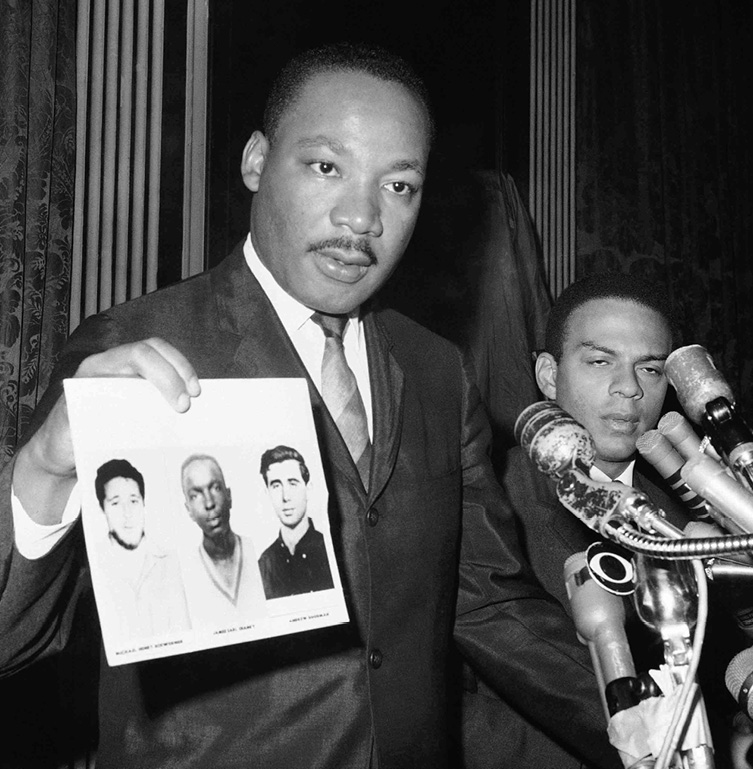

Lives on the line: Dr. King displays a photo of three murdered civil rights activists, December 4, 1964.

TB: He knew Chicago pretty well. It was kind of the center of black culture in the North. But he also went to Boston. He tried out six cities as the best laboratory to demonstrate that there was racial conflict and ghettoization in northern cities.

He went to Boston, he went to Rochester, he went to Philadelphia, and he went to Cleveland, in addition to Chicago. Ultimately he picked Chicago, and was subjected to what he said was the worst violence that he ever saw in trying to march for integrated housing in Chicago.

But he said, “At least we proved two things. We proved that there’s a lot of racial feeling in the North, and we also proved that the northern press will not cover civil rights demonstrations as sympathetically in Chicago as they did in Selma.” The press turned on him. He said, “That’s a price we will willingly pay.”

DR: Later, in 1968, he gets involved in a sanitation workers’ dispute in Memphis. Why did he get in the middle of that?

TB: By that time, he was in his poor people’s campaign. The end of King’s career is a series of witnesses—bearing witness to things that he knew he had already lost the momentum to change in his lifetime. He came out against the Vietnam War very publicly.

Then he said he wanted to leave behind a witness on poverty—that the government could be a positive force to relieve poverty. His model, believe it or not, was the Bonus Army marchers of World War I, who came to Washington in 1932 during the Great Depression and got run out of town. [Many of the marchers were desperate out-of-work veterans who wanted the government to redeem bonus certificates it had issued for their wartime service.]

That was part of the gestation of the G.I. Bill. King said, “If we come to Washington, we’ll be run out of town too, but maybe the equivalent of the G.I. Bill will come out of this in the future.” That’s what he was doing.

Memphis laws at that time did not allow sanitation workers, all of whom were black, to seek shelter during rainstorms, because it offended the white residents. During a particularly terrible storm, the “tub men,” the ones who carried the tubs of garbage, wouldn’t fit in the cab of one truck, and two of them had to get in the back, and their broom hit the compact lever and they were compacted with the garbage.

That precipitated the strike in February of 1968. When you see these signs that say, “I am a man,” that’s the origin of that slogan. It was not just “I am a man.” It means “I am a man, not a piece of garbage to be compacted in the back of this garbage truck because we can’t seek shelter and we have no rights.”

King felt that he couldn’t resist that. He went to support those people, and that’s what he was doing when he was killed.

DR: Do you have any doubt that James Earl Ray killed Martin Luther King Jr. alone?

TB: No. It’s virtually certain that he had aides and accomplices, but more or less at his own level, which was a petty-criminal truck-stop type thing. Not SMERSH, or a helicopter company from Texas, or Russians, and God knows who else fits in a conspiracy theory.

I don’t believe in the conspiracy theories, and neither did King when he was alive. He said, “Conspiracy theories are belief in the devil, and they relieve people from the obligation of confronting the problem as it is.”

DR: King was almost stabbed to death in 1958 in Harlem. Had the knife gone a half inch another way, he would have been dead. Had he been killed, would the civil rights movement have occurred much differently? How would history be different had he not lived in the sixties?

TB: Wow. You are really tough. The civil rights movement would have been different. It was percolating, and there would have been more protests. But King was the effective public voice.

The best way I know to talk about how he did it was that he consistently put one foot in the Scriptures and one foot in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, in a balanced way that invited people to understand the mission for equal citizenship, either in secular terms or spiritual terms. They could take their choice. He didn’t try to subdue one with the other. It was the gift of his rhetoric that made it seem both religiously and spiritually inspiring, and patriotic in a way that people couldn’t resist.

It’s that patriotism that we’ve really lost today. It made him a leader for all of us, not just for black people trying to get rights about quaint things that no longer apply. It’s about the future, not about the past.