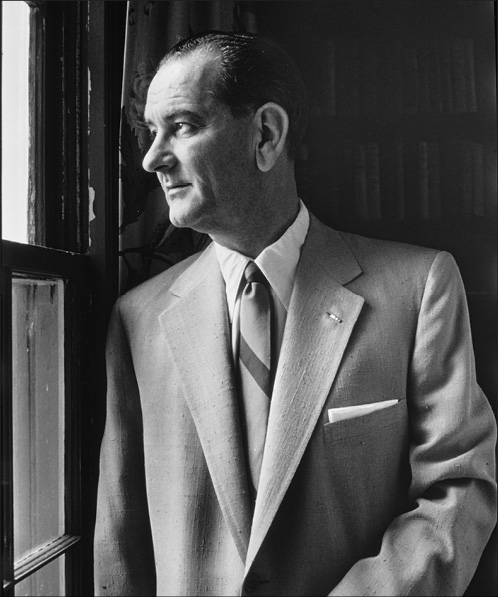

13 ROBERT A. CARO on Lyndon B. Johnson

“I never had the slightest interest in writing a book just to tell the story of a famous man. I was interested in political power.”

BOOKS DISCUSSED:

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (Knopf, 1974)

The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volumes 1 to 4

The Path to Power (Knopf, 1982)

Means of Ascent (Knopf, 1990)

Master of the Senate (Knopf, 2002)

The Passage of Power (Knopf, 2012)

Robert Caro is as legendary and respected a biographer as is alive today—and not just because of his epic, Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker. That biography, the result of seven years of research and writing, was so detailed, dramatic, and interesting in its description of the unelected official who built much of New York’s infrastructure during the 1950s and 1960s that Time magazine named it one of the one hundred best nonfiction books ever written.

It might fairly be asked how one could top that achievement. Some authors (e.g., Margaret Mitchell, Ralph Ellison, and Harper Lee) published first books that made such an impact that they found it almost impossible to publish a second book.

Fortunately, that was not the case with Robert Caro. After The Power Broker, Caro embarked on a mission, now forty-five years in the making, to produce the definitive biography of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

To date, four volumes have been researched, written, and published—all by an author who does his own painstaking research, along with his wife and longtime research partner, Ina Caro; and who writes on a no-longer-manufactured (and thus difficult to repair) Smith-Corona typewriter. These four volumes—The Path to Power, Means of Ascent, Master of the Senate, and The Passage of Power—have each received awards (including a Pulitzer Prize for Master of the Senate) and highly favorable critical commentary.

In our interview, Robert Caro discusses why he became interested in Robert Moses and, later, in Lyndon Johnson. Both were studies in how to obtain, consolidate, and use power. For Moses, it was local power. Caro, in seeking his next subject, wanted to see how power was mastered at a national level. Little did he realize at the outset that mastering Lyndon B. Johnson would take more than four decades.

Caro describes in the interview a young Johnson interested in power almost for power’s sake. He got elected to the House of Representatives and quickly became a protégé of the Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, and, to some extent, a favored congressional supporter of the president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

That his mentors’ views were somewhat different did not bother Johnson. They had power, and some of it could rub off on him.

When he was elected to the Senate in 1948 by 87 votes (made possible, Caro points out, by getting 200 of 202 votes in one precinct where the voters apparently voted in alphabetical order), he quickly figured out that the power there was held by Senator Richard Russell. So Johnson quickly became Russell’s protégé and best friend, despite Russell’s ardent segregationist views.

Within six years of becoming a senator, Johnson became the Senate majority leader—an unrivaled ascent in the modern era. And he became the most powerful majority leader in anyone’s memory.

The only way for him to get more power, Caro relates, was to become president. Johnson thought this would happen in 1960, for his rival for the Democratic nomination was an often absent, frequently ill, and ineffective figure in the Senate—John F. Kennedy.

But, as Caro notes, Kennedy did master the nomination process, and Johnson had to settle for the vice-presidential nomination. Although his Texas base helped Kennedy to hold the South in 1960, Johnson became a vice president with little to do and with far less power than he had wielded in decades.

That changed, of course, when he became president and once again had real power. Johnson was back in his element, often subjecting those from whom he needed something to the famous “Johnson treatment.”

Despite the humiliations he suffered during the Kennedy presidency, Johnson resolved to use his power to push the Kennedy agenda through Congress. He succeeded in doing so most visibly with the civil rights legislation that seemed so inimical to Johnson’s roots and to the views of his closest supporters in the Senate.

Caro observes that Johnson did not just do this to honor the Kennedy legacy—though that was a factor—but because he had resolved as a young man that if he ever had the power to help the poor and disenfranchised, he would do so. “What is the point of having power if one does not use it?” Johnson would regularly say to his closest advisors.

In the interview, Caro did not discuss Vietnam very much, for he had not yet finished the volume dealing with the subject that ultimately drove Johnson from office and damaged his legacy as president. Caro’s definitive conclusion about Johnson and about Vietnam will presumably come in the long-awaited fifth volume.

Caro is now researching and writing that volume, presumably the final book in this epic series on our thirty-sixth president. The publication date has not been announced, but Caro is now eighty-three, and intent on publishing this much-anticipated work on the Johnson presidency in the near future. (To the surprise of many hoping that he would complete the fifth volume soon, he published a different book this year—Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing, an informal memoir. He expects to write a full memoir at some point.)

The difficulty in interviewing Robert Caro is trying to get him to distill forty years of work in about forty-five minutes. That was the mission when I interviewed him on November 3, 2015.

Caro clearly has an uncommon command of the details of his subject’s life, and that comes through in the interview. What also comes through is the biographer’s admiration for Johnson’s highly developed political and legislative skills, though he fully recognizes that Johnson was not without his flaws and failings.

What does not come through is the respect, indeed awe, that the members of Congress who attended the interview have for Robert Caro. That was evident from the number who brought their dog-eared copies of his books in order to get them autographed. None of them knew Johnson, but all of them were familiar with (and admiring of) the kinds of legislative skills that he used to work his way in Congress.

Unlike many of the authors interviewed for the Dialogues, I really did not know Robert Caro well beforehand. But like the members, I greatly admired and had read all of his books. I particularly admired his commitment to mastering details through laborious, first-person research, and his persistence in writing without the aid of modern technology.