“He had the idea that he was untouchable.”

MR. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN (DR): I think it’s fair to say, Bob, that in the lifetime of everybody in this room, you’re the most famous journalist our country’s ever produced. You didn’t go to journalism school, and you weren’t really a journalist when you were in college. Your father was a lawyer and a judge, and I think expected you to go to law school. How did you wind up as a journalist rather than a lawyer?

MR. BOB WOODWARD (BW): Good luck, I think, is the best answer. I was in the navy. I was going to go to law school after five years in the navy. It was during the Vietnam era, and I was, quite frankly, unhappy with myself that I couldn’t do something about the Vietnam War.

I worked here in Washington in the Pentagon for the last year. I was reading this newspaper called the Washington Post, and they said there’s a guy named Bradlee there who’s called “the rocket thruster.”

I went and asked for a job. I had no experience. They gave me a two-week tryout and I failed. I went to the Montgomery County Sentinel for a year, and the Post hired me back.

DR: When you went back, were you on probation?

BW: In a sense. It’s like being in Congress. You’re always on probation.

DR: So one weekend in June 1972 there’s a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate. How did you and Carl Bernstein happen to be assigned to cover that?

BW: I’d been at the Post nine months and really enjoyed the work. I was covering the night police beat from 6:30 at night till 2:30 a.m., and I would come in during the day and work on follow-up stories.

The morning of the Watergate burglary—June 17, 1972—was a Saturday morning. It was one of the most beautiful days in Washington. The editors had this strange burglary to cover, and they thought, “Who would be dumb enough to come in and work today?”

My name immediately came to the lips of a number of people. So I got called in.

DR: They said you should cover this with Carl Bernstein?

BW: No. The first day there were a group of people covering it, and then on Sunday there were only two people who came to work—Carl and myself.

DR: As you began to investigate it, at what point did you realize it was more than just a break-in by some average citizen? When did you realize there might be a connection to the White House?

BW: It was immediately obvious that there was a connection to the White House, but of course they denied everything. The reporting was incremental over two years. Sometimes each piece or story advanced it in a significant way, sometimes the stories were marginal.

DR: There are stories about how when you’d written about Watergate, and the famous movie about it came out [the 1976 movie All the President’s Men, starring Robert Redford as Bob Woodward and Dustin Hoffman as Carl Bernstein], you would go knock on people’s doors, and sometimes they’d let you in and sometimes they’d shut the door. How complicated was it to knock on somebody’s door and get them to let you in?

BW: It’s hard, rejection. I’m sure it’s like when you knock on someone’s door and say, “I’d like to invest in your business,” they’re reluctant to let you in. In this case they were sometimes reluctant, but significantly it was the look on their faces of anguish and pain and “Don’t bother me.” It was clear the lid was on from the White House.

DR: One time you and Carl Bernstein wrote an article that wasn’t quite accurate, and the White House went after you. Did the Washington Post support you? What was the inaccuracy?

BW: It was a misattribution involving Nixon’s chief of staff, Bob Haldeman. It was a very serious error, because we said somebody had testified about something involving Haldeman to the grand jury—and they had not.

The substance was true. It was a very interesting moment because Ben Bradlee, the Post’s executive editor, looked at this and said, “We stand behind the boys.”

We didn’t actually deserve that support. We’d made a serious mistake. We couldn’t prove a lot of this.

I’m sure everyone in their life has had somebody—a boss, a friend, a spouse—stand by you in a way that maybe you knew you didn’t deserve. But it accelerates your devotion to the cause and to the person. In this case, it was a very generous act on the part of Ben Bradlee.

DR: As you and Bernstein were writing these articles, where was the New York Times? They’re a pretty good newspaper. How come you managed to outmaneuver them so much?

BW: I don’t think we outmaneuvered them. We were young. If you look back at the clues, so much of it was obvious. The New York Times had people on it and did some very good stories. But, you know, it consumed us.

And, again, this is a leadership question. Bradlee and the Post’s editors were very much of the mind-set “What’s going on with Watergate? Let’s get to the bottom of this.” They were saying that and demanding answers.

DR: Your articles were criticized by some for using unnamed sources. Was that a common technique before you began doing it, or was it relatively new?

BW: It was common in diplomatic reporting and political reporting, but this was necessity. Our sources were not going to allow their names to be used. And the editors of the Post understood that.

DR: One of your famous sources was somebody who was known as Deep Throat. Did Deep Throat call you up and say, “I’d like to see you in a garage”? How did that come about?

BW: No. He was somebody I had met as a courier at the White House—Mark Felt, who was number two in the FBI later. He was not a volunteer source. I was a pest. I had his phone number, and he helped on one initial story on the White House connection involving Howard Hunt, who was one of the supervisors of the Watergate burglary.

Because I was such a nag, Felt said, “Let’s meet in this garage and set up these very complicated signals.” Again, I was starting out, and I thought this was kind of common practice.

DR: Washington is not famous for keeping secrets, I think it’s fair to say. But you and Carl Bernstein managed to keep the secret of who Deep Throat was for thirty-some years. How did you manage to do that? What was it like when everybody came up to you and said, “I think it’s X” or “I think it’s Y”? How did you respond?

BW: I said, “We’re not going to talk about it.” It was part of the rules of engagement. I did tell my wife, Elsa, who is here. I told her on about our fourth date.

DR: Wow, okay. You kept that secret for a while. Why ultimately did you decide to write a book about it and expose Deep Throat’s name?

BW: He came out and identified himself, Mark Felt did.

DR: Let’s talk about the Nixon tapes for a moment. Why did Richard Nixon tape so many of his White House conversations?

BW: There are two elements. He wanted to write the best memoirs a president had ever written. He knew that the process of getting people to take notes at meetings was insufficient.

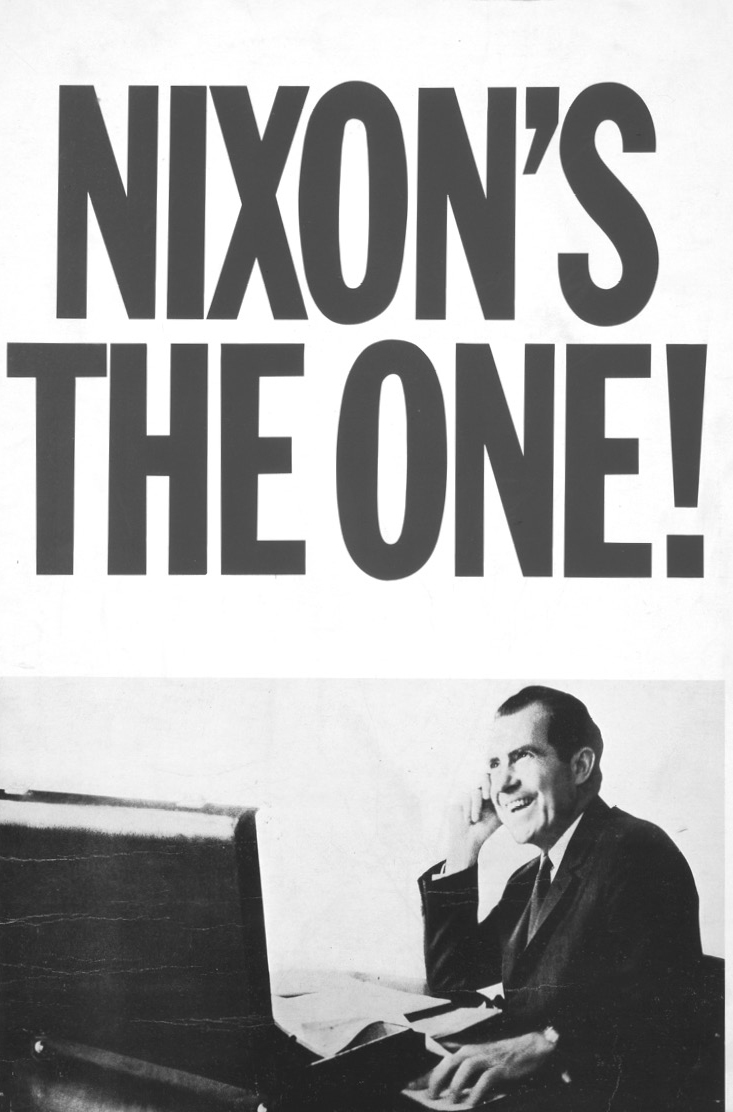

But most importantly, I think, he had the idea that he was untouchable. He was president of the United States. He thought no one would ever find out about these tapes, let alone get access to them.

So he kind of cruised along. If you listen to any of these tapes, it is a shocking story. In fact, in the end, Nixon resigned not because of the media or the Democrats. It was the Republicans.

DR: When it was exposed publicly for the first time that he had the tapes, why didn’t he just burn them?

BW: I think part of it is that he was so deluded, he thought they would exonerate him.

DR: The man who exposed the tapes was a man named Alex Butterfield, an aide to President Nixon. He testified before the Senate Watergate Committee and he said, yes, there was a taping system. Recently you wrote a book about him, and he shared with you that he’d been holding a lot of documents for thirty-plus years. Why did he call you, and what did you learn from his documents?

BW: He didn’t call me, I called him. There’s this idea that reporters sit around and wait for Daniel Ellsberg to come in with a grocery cart of documents. [Ellsberg was an analyst for the RAND Corporation who, in 1971, leaked the Pentagon Papers, a secret government report on the Vietnam War, to the New York Times.]

I’d been waiting a long time for that to happen. You have to go out and find sources. These people are not volunteers.

DR: What did Butterfield tell you all these years later that you didn’t already know?

BW: All kinds of things. He told me stories that were almost not credible until you saw the documents.

For instance, he said that Nixon threw a fit because some staff members had pictures of John F. Kennedy in their offices. There actually is a memo where Butterfield reports to Nixon that he got these pictures out. The subject of the memo is “Sanitization of the Executive Office Building.”

Nixon thought these pictures, somehow, were disloyal. It’s almost unthinkable. Suppose you’re gone and somebody else comes along and runs the Carlyle Group and someone has a picture of you in their office. Do you think your successor would say, “We have to sanitize”?

DR: I’m not sure.

BW: Hopefully not. Hopefully there would be enough self-confidence and comfort to say, you know, “That’s the old guy.”

DR: What did it feel like to have a movie written about this and to be played by Robert Redford? What was that like?

BW: You have no idea how many women I have disappointed. Universally, they thought there would be some resemblance and were horrified rather than disappointed to discover that there was no resemblance.

DR: You wrote a book about the final days of Nixon. Who was really running the White House in that final year and a half or so? Was the president really in control of things, or was it Alexander Haig?

BW: Al Haig was the chief of staff. He was running lots of things. But it’s a sad story about the disintegration of power and the disintegration of Nixon.

In a blizzard of self-knowledge, the day he resigned—if you’ve seen the video of it, Nixon was there, his daughters, his sons-in-law, his wife—and he gave a speech with no text. It was Nixon raw. He talked about his mother and his father and was very maudlin.

Then, near the end, he kind of waves his hand like, “This is why I called everyone here. This is the message I have to say.” Then he said, “Always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”

Now, the wisdom in that could not be larger, because Nixon did destroy himself. At that moment, he said, the hating was the poison that did him in.

We’ve had lots of presidents, and we’ve had lots of disagreements, and there’s a lot going on. I tried to write about and understand some of the other presidents, but none of them were haters like Nixon. He just could not get over the fact that people would cross him or disagree with him. He had no sense of the wonderful feelings of goodwill that people had, even Democrats.

DR: He resigned in August 1974. In all the years after he left office, did you ever meet him?

BW: No.

DR: He never called you and said, “Let’s talk about old times,” or something like that?

BW: When we were doing reporting for our books, we tried to talk to him, and it was always no. We did not even get on his Christmas card list.

But when he gave his famous interviews to TV host David Frost, at one point Frost asked him about Carl and myself. Nixon said, “That’s Washington. That’s politics. That’s the Washington Post. They’re liberals, and what they write is trash, and they are trash.”

I called my mother to get some comfort. I said, “What did you think about Nixon calling us trash?” She said, “That’s Washington. That’s politics.” Pause. “What’s this about being a liberal?” Mother could always figure out what the problem might be.

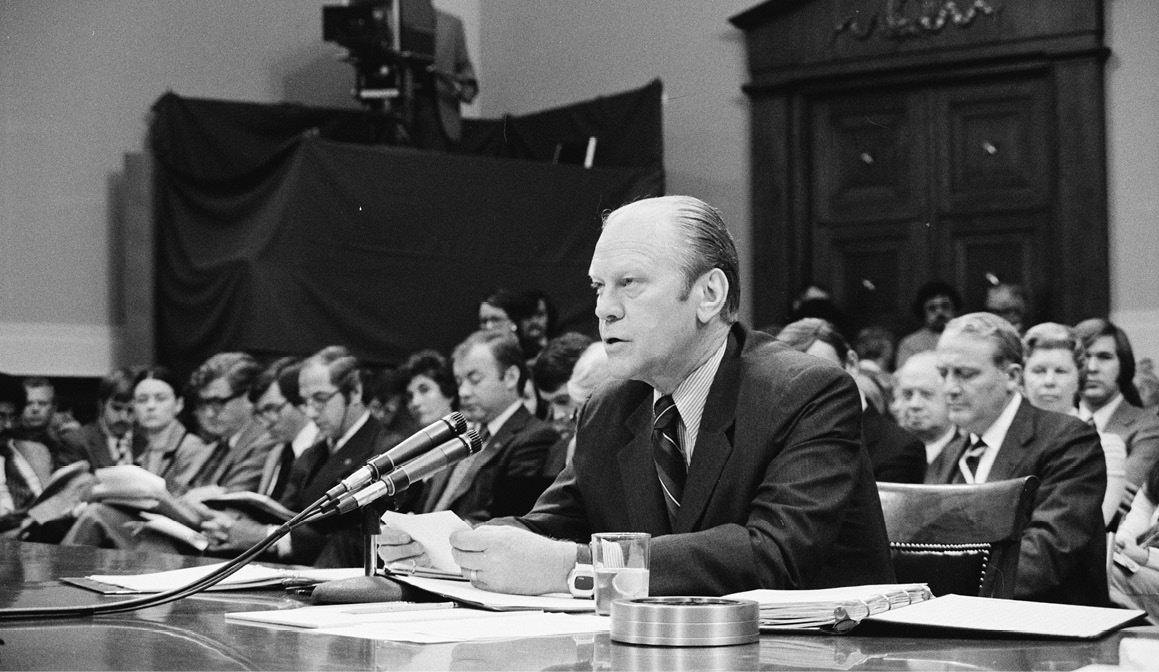

DR: Before he got on the plane the day he resigned, do you think he had a feeling that President Gerald Ford was going to pardon him? Was there a deal cut before he left office?

BW: There actually was not a deal. There was suspicion that there was a deal. I did a book twenty-five years after this called Shadow and spent lots of time investigating this.

It was a Sunday morning, Nixon had been out of office for a month. Ford was president. Ford went on television on Sunday morning announcing a full pardon for Nixon.

I was asleep. My colleague Carl Bernstein called me up and woke me and said, “Have you heard?” Carl—who then had and still has the ability to say what occurred in the fewest words with the most drama—said, “The son of a bitch pardoned the son of a bitch.” And I even got it.

In October 1974, President Gerald Ford testified in front of the House Judiciary Subcommittee about pardoning Nixon—a decision that helped push the Watergate story off the front page.

I thought this was the most corrupt thing, you know, perfect. Nixon, who led all of this, gets off, and all these other people go to jail. Then I looked at it twenty-five years later and, when you really dig into it, you realize that what Ford did was quite a courageous thing, in the country’s national interest, to get rid of Nixon and Watergate, to get them off the front page.

I interviewed Ford many, many times, and I will never forget him saying, “I had to get rid of Nixon. I had to preempt the process.” He said, in this plaintive tone, “I needed my own presidency.”

DR: Did Ford tell you that, had he not done the pardon, he would have been reelected? Did he believe that?

BW: No. What he did tell me is that Al Haig, who was Nixon’s chief of staff, came and offered him a deal. And Ford said—convincingly—that he rejected the deal.

DR: After Watergate, you wrote another book on a different branch of government, and that’s the judiciary. You wrote a book on the Supreme Court called The Brethren. In it, you have a very interesting passage about a case involving Muhammad Ali. You might describe that. [Ali died on June 3, 2016, a few days before this conversation took place.]

BW: If you read the stories in the last week about Ali, it said the Supreme Court overturned his conviction for draft-dodging. He had been convicted. It was in the court system.

What I find most interesting about this is how it illustrates the large theme: we don’t really know what goes on. There’s a behind-the-scenes that is always much richer and real.

In the case of Ali, we were able to talk to 140 law clerks and five of the justices and get lots of documents. It turns out that, yes, Ali got off at the end, 8 to 0, but it started out where they were going to send Ali to jail.

The first vote at conference was 5 to 3. Justice Thurgood Marshall, because he’d been solicitor general, was out of the case, so there were eight justices voting. Chief Justice Warren Burger gave the assignment of writing the opinion to Justice John Marshall Harlan II, a very conservative justice, and everything seemed to be fine.

Then a clerk read the literature that Ali cited as to why he was a conscientious objector—that it was part of the Black Muslim religion. The clerk said, “Ali is a legitimate conscientious objector.” He gave this material to Harlan, who at this point was nearly blind and could not read.

Harlan took all this stuff home and, under this intense light he had, read it and came in and said, “Ali is a legitimate conscientious objector. I’m switching my vote.” So instead of 5 to 3, it’s 4 to 4. As we know and are reminded now, when the Supreme Court is split 4 to 4, it upholds the lower court opinion, which was to send Ali to jail.

But [in that situation] there’s no written opinion from the Supreme Court. Justice Potter Stewart said, “This isn’t right. We need to find some way to explain what we’ve done.” He found a technicality and switched his vote.

So now it was 5 to 3 the other way. Two of the other justices quickly got on board, so it was going to be 7 to 1 to free Ali. Chief Justice Burger said, “People are going to think I’m a racist. So I’ll join the 7,” making it 8 to 0.

The day it was announced, Ali said, “I thank Allah and the Supreme Court of the United States.” He had no idea that he was heading to jail.

The reversal of his conviction brought him back. Everything he did in the seventies was made possible because of that.

DR: In The Brethren, you also talk about the Roe v. Wade case. When that was decided, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the opinion. Did that vote switch back and forth as well?

BW: It was immensely complicated. The Roe v. Wade opinion is not a legal opinion, it’s a kind of doctor’s opinion.

Harry Blackmun was very close with doctors—people at the Mayo Clinic—and wanted to make sure that doctors had the right to practice what they thought was correct. That is really the root of the abortion decision.

DR: You began writing books about the Nixon administration, and subsequently you wrote a number of books about other administrations. You also wrote a book about the CIA under Ronald Reagan. Do you think Reagan knew about Iran-Contra or not? [In the Iran-Contra affair, the administration arranged for covert arms sales to Iran, which was under an arms embargo, and used the proceeds to support the U.S.-backed Contra rebels in Nicaragua.]

BW: I think he did not know, or he did not remember. Casey [William Casey, director of the CIA] was one of the truly most interesting characters, somebody who was very elusive but agreed to let me talk to him. He would scream and yell at me and run away from me, and then have me over to his house for dinner.

DR: And he mumbled all the time. How did you understand what he was saying?

BW: You could just say, “Could you repeat that, please?” And then he would repeat it.

DR: You wrote a book, The Commanders, about what happened in the Kuwait war—the Gulf War of 1990–91. Why did that war seem to work so well, in the sense that it got done the way it was supposed to get done, relatively few Americans were killed, and the mission was more or less accomplished? Was the administration’s team working together so well?

BW: This was George Bush Senior’s war, and the team did work well together. The theory of the case, held by Colin Powell, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was that we had to send a force that was absolutely decisive. So we sent nearly five hundred thousand troops and airmen and navy men over to the Persian Gulf, and the war lasted, what, forty-two days?

DR: How did we get people to pay for it? The Saudis and others paid for the war?

BW: Most of it, yes. Jim Baker used to say we “tin-cupped” it. He was Bush’s secretary of state, and he went around the world with his tin cup and the Saudis and others filled it up.

DR: When the September 11 attacks occurred, you wrote a book about that. Do you think that U.S. intelligence capability today is such that we could have pieced together the intelligence and prevented that from occurring? Or are we still as vulnerable as we were before 9/11?

BW: It’s a great question, and the answer is, I don’t know. Let me just skip ahead to President Barack Obama, because I think this is important. I was thinking about this.

When I interviewed Obama for Obama’s Wars, the focus was really his decision-making in the war in Afghanistan. But out of the blue, not in response to a question—this is a question I should have asked, stupid me—he said, “You know what I worry about at night? What I worry about the most is a nuclear weapon going off in an American city.”

He said that would be a game-changer. He then went further and said that a significant number of our intelligence operations are geared to keep that from happening.

DR: Staying on Obama for a moment, how obsessed was he about getting Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaeda leader behind the 9/11 attacks? Was it really a matter of luck? Was it a courageous decision to go after bin Laden in light of the intelligence Obama had?

BW: A lot’s been written about that. Again, like Ali or Nixon or any of these things: the full story has not been written.

My curiosity about the bin Laden raid is that they learned that bin Laden was probably at this place in August 2010, and the raid was not until May 2011. [A team of Navy Seals killed bin Laden in Pakistan during a covert operation on May 2, 2011.] Why would it take so long if you could be sure where he was?

They said, “Well, we weren’t really sure,” but they had satellite photos. They called him “the pacer.” He was visible on satellite photos pacing back and forth in the compound. It was pretty clear it was him. So I think there are things we don’t know about that, quite frankly.

DR: Okay. Back to 9/11. When President George W. Bush was informed about the attacks, he was reading to these young children at a school in Florida. After he was informed by his White House chief of staff, Andy Card, he didn’t get up and rush out. He stayed there frozen for a while.

His explanation was he didn’t want to scare anybody. Do you accept that explanation, or do you think he wasn’t really prepared to deal with it?

BW: I’m sure he, like most people, didn’t know what it meant, whether it was true. It was incomprehensible in many ways.

DR: Later, the Bush administration’s strategy was to go into Afghanistan. That worked, but it didn’t get Osama bin Laden. Was Bush obsessed with getting bin Laden?

BW: No. It was symbolic but probably not strategically that significant to take out Osama bin Laden.

DR: You wrote another book, Plan of Attack, about Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003. Why did the intelligence community make such a big mistake in thinking that there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?

BW: Because they knew that Saddam Hussein had had weapons of mass destruction. It seemed logical. [Hussein, the strongman president of Iraq from 1979 to 2003, was toppled by the U.S. invasion.] They did not look at alternative explanations seriously.

And there was a momentum to war. George Tenet, the CIA director, memorably told the president that the intelligence was a slam dunk. You notice that when people are talking about politics now and they’re sure about things, they don’t use that term anymore.

DR: Do you think President Bush would have invaded had he known there were no weapons of mass destruction there?

BW: In hours of interviews with him, I asked him about that. His answer was, “We’re better off with Saddam not in power.”

If you really look at it—and I looked at the war plans and interviewed people and interviewed Bush for, as I said, hours on that—the explanation for the Iraq War is momentum, that the military told Bush at the beginning, “Oh, it’s going to take a year, it’s going to be complicated.” Then they said it would be faster and much easier.

Each time the top-secret war plan was presented to President Bush—the code word, interestingly enough, was Polo Step—each time the Polo Step plan came to him, it looked easier and easier. I chart in detail in the book what happened each day, what Bush thought, what his reactions were.

There was no one in there saying, “What about an alternative explanation?” And I quite frankly think, in our politics today or anything else, you have to go for that alternative explanation.

DR: Was Bush ever briefed on the difference between Shiite and Sunni Muslims? Was that ever included when he was briefed about the possible problems of invading?

BW: The focus was, for him, Saddam Hussein. He became obsessed with this.

DR: The surge strategy was later used. Who do you think deserves the credit for the surge more or less working? Had it not worked, what would have been the result?

BW: To a certain extent, we know now, the surge actually didn’t work. The drop-off in violence in Iraq was attributable not to the addition of these twenty to thirty thousand troops but to top-secret intelligence operations to locate the leaders, and to the Sunni Awakening movement and some other things that happened. If you really look at that, the surge as something that put us on a better track in Iraq is a myth.

DR: You’ve met with many presidents, interviewed them. Could you give us your impressions of the great features and the weaknesses of the presidents that you have met or interviewed?

Let’s go over Nixon first. You didn’t meet him, but what would you say his greatest strength was? What was his greatest failing?

BW: The hating was his greatest failing. It just doesn’t work. It doesn’t work in politics. It doesn’t work in your personal life. There is a great lesson for everyone in studying Nixon.

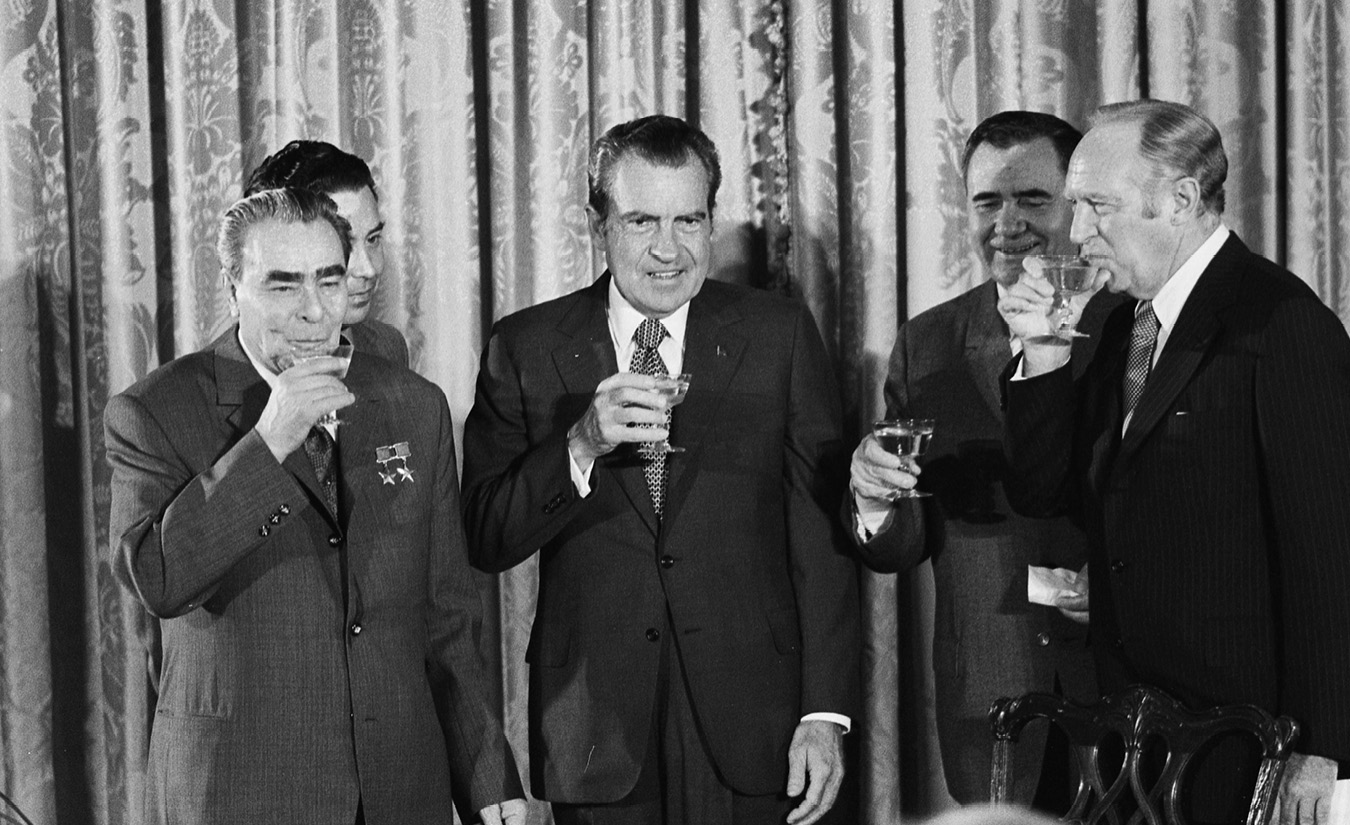

DR: Any strengths you’d mention?

BW: Sure. He did some important things in foreign affairs. But he was a criminal, a provable criminal.

Barry Goldwater, of all people, had Carl Bernstein and myself up to his apartment here in Washington and read his personal diary about the last days of Nixon and what happened when he and other Republican leaders went to see Nixon.

It’s an astonishing scene, because this is August 1974. Nixon knows he’s going to be impeached in the House. The question is what the Senate will do, as is always the question.

The Watergate scandal overshadowed Nixon’s foreign policy accomplishments. Here he is in 1973 with (left to right) Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, Soviet minister of foreign affairs Andrei Gromyko, and Secretary of State William P. Rogers, toasting the signing of U.S.-Soviet agreements on oceanography, transportation, and cultural exchange. June 19, 1973.

Nixon said to Goldwater, “Barry, so what do I have in the Senate? Twenty votes?” He needed thirty-four to keep from being removed from office. Goldwater said, “I just counted. And, Mr. President, you have four votes. And one of them is not mine.” The next day, Nixon announced he was resigning.

DR: What about Gerald Ford? Greatest strength?

BW: Courage. Democrats acknowledge this, with the pardon he made with the national interest in mind.

DR: What about Jimmy Carter?

BW: Whom you worked for when you were a very young aide who wrote, as I recall, a memo to the president suggesting a war on OPEC.

DR: Well, somebody leaked it to you, and you wrote about it. But yes.

BW: How old were you then?

DR: Twenty-seven or twenty-eight.

BW: Twenty-seven, twenty-eight—what an age to have that wonderful lesson of the cleansing power of a leak. Right? You didn’t feel that way at the time.

DR: I thought I would lose my job, but that’s another matter. Maybe a war on OPEC would have worked, but that’s a separate issue. So, your impression of Carter?

BW: Carter gets a bad and unfair rap on lots of things—and, you could argue, correctly on a number of things.

But the Camp David Accords of 1978, where he invited Menachem Begin, the Israeli prime minister, and Anwar Sadat, the Egyptian president, to Washington—they went up to Camp David for two weeks, and came up with, effectively, a peace treaty between the two countries. A big step forward.

I remember asking Hamilton Jordan—your boss, the chief of staff, who had a side of him that could be very candid—I said, “How did Carter pull this off?”

He said, “Look, if you’d been locked away at Camp David for thirteen days with Jimmy Carter, you too would have signed anything.”

Now, there’s a lot of truth in that. What I think is the lesson, and very much to Carter’s credit, is he was able to set a priority. He was able to say, “It’s worth spending two weeks to really do this.”

If you look at their schedules, presidents will spend maybe a half a day on something—fifteen minutes there, some calls here. It is a pressure cooker, to say the least. Presidents more often should say, “This is really the most important thing going on. Let’s try to fix it. Let’s spend time on the problem.”

DR: What about Reagan?

BW: Can I ask a question? How many people here have been involved in a negotiation at one time in your life? Raise your hands. How many people are married? It’s the same question.

And what do you learn in a negotiation? That you have to spend time, you have to listen. It gets down to one for you, one for me, one for you, one for me. That’s how you solve things.

What Reagan did is he attacked Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev verbally: “The Soviet Union is the evil empire.” Then he negotiated with him. He attacked the Democrats, and then he negotiated with Tip O’Neill, the Speaker of the House. As he said, the purpose of a negotiation is to reach an agreement. And that seems to be a new idea.

DR: What about your impression of George Herbert Walker Bush? Did you spend much time with him?

BW: He would never be interviewed by me. He had been the Republican National Committee chairman during Watergate and spent a lot of time going around defending Nixon. That was his duty, and I think that had an effect.

What he did in the First Gulf War was a model for how to go to war: keep it short. I think he bungled the economy, or appeared to bungle the economy, and that’s why Bill Clinton beat him.

DR: What was your impression of Clinton?

BW: Can I use the line “easier to describe the creation of the universe”? What’s so interesting about him is that his eight years as president were peace and prosperity, by and large. But the Monica Lewinsky business is going to be in the first paragraph of his obituary. [Clinton’s relationship in 1995–97 with Lewinsky, then a White House intern, caused a major scandal and contributed to impeachment proceedings against the president in 1998.]

Somebody was asking me today what I think the ratings are going to be for the presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. It’s going to make the Super Bowl look like an afternoon soap opera.

Trump is going to attack her, presumably: “Crooked Hillary” and “Look at all the things your husband did” and so on and so forth.

Somebody was saying, “How can Hillary Clinton deal with that?” Somebody said, “Let Trump go on and Hillary could say, ‘I forgave Bill, and that was very hard, but I forgave him.’ ” That would maybe end that issue.

DR: Two final ones. George W. Bush—what is your impression of him?

BW: He was the most open person when I wanted to talk to him. He made a mistake in Iraq, and a significant one, and we still have that problem.

DR: And your impression of Barack Obama?

BW: As one of his aides says, “Obama has the armor of a good heart.” I think he really does. If you look at his first inaugural address, where he says that “we’re going to be known for our good deeds and the justness of our cause and our sense of restraint”—it’s not the way the world works.

I remember, a couple of years ago, having breakfast with one of the world leaders who is one of our best allies. I said, “What do you think of Obama?” He said, “I really like him. He’s really smart. But no one’s afraid of him.”

There’s a lot of truth in that—the message in this world we learn as parents: sometimes you have to be tough and you want your kids to be afraid of you.