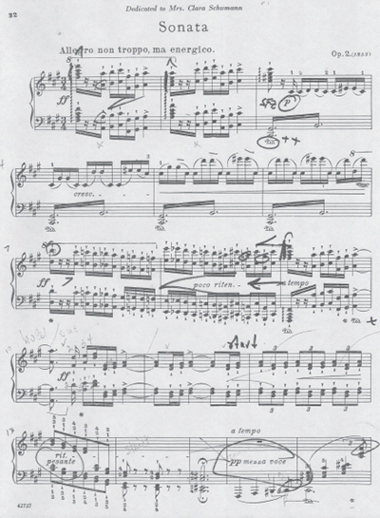

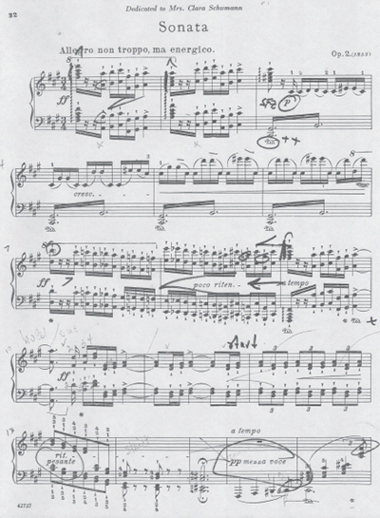

Fig. 18.1. Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 2, from Piano Works In Two Volumes by Johannes Brahms, Edited by E. V. Sauer

Brahms, actually, is our language today. I would say he’s the most popular composer in that sense. And that which he himself felt as a weakness—not being as varied and as profound as Beethoven—to us doesn’t mean anything. To us, he is very profound, he is very varied. And so we play his works, and each time we feel absolutely fulfilled, and it doesn’t matter if it is a symphony or his piano concerto or an intermezzo, quintet, quartet, trio, sonata. He has been one of the great ones, yes? His lyricism, the variety of his harmony, the form are all sublime. Of course, he couldn’t compare himself to Beethoven. And why should he? And why would we? I mean, Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, they are incomparable, and Brahms is incomparable.

PERFORMING BRAHMS’ CONCERTO NO. 2 IN B-FLAT MAJOR

Let me tell you how that is performed. I have heard many, very good performances, many excellent performances. I was talking about the performance of Mr. Serkin, who was playing in New York with the Philharmonic, and it was one of those performances when you feel that it could have been created just at that moment. And he was playing it like Parsifal; he was defending the Holy Grail. And he was hearing Brahms the way it should be, and it was so wonderful to see him when he played those octaves. He was so wild that his cufflinks were hitting the keys and [one] heard people laughing, but not me.

To me the performance was absolutely unforgettable because he expressed all that is in that music, where a young composer takes on the whole world. And it’s wonderful that we know that Brahms played the first performance. When you play in Leipzig at the Gewandhaus, . . . you take that terrible walk to the stage, and you see the picture of the program, Brahms premiering his Concerto in Leipzig with the Gewandhaus Orchestra. It was not a success. It was absolutely a disaster. The public didn’t like it, and the critics were horrifyingly bad. And even Clara [Schumann] said to him, “You’ve got to change it.” And you know, he didn’t change one note, although he always listened when he couldn’t play anymore, and they tried to honor him. He played both concerti in Leipzig. He said, “Oh, I played terrible.” He probably did, because he didn’t practice. But he played both and it was a big success. So perseverance counts for something.

Mvt. 1. Allegro non troppo, ma energico

M. 1. Roll the left hand, but play the right hand as a solid chord with a strong accent. Crescendo to the last octave, while leading with the thumbs.

M. 2. Play the chord the same as in m. 1.

M. 3. Play the chord with a sforzando. Use two or three changes to clear the pedal.

Mm. 4–6. Climb up melodically C![]() -D-E

-D-E![]() -G

-G![]() -D-E

-D-E![]() , etc.

, etc.

Mm. 6–7. Broaden and emphasize the last D. Begin the octaves less.

M. 8. A very big crescendo at the end of the measure. And broaden into the downbeat. Hear the A-G![]() going to the F

going to the F![]() of m. 9.

of m. 9.

M. 9. Have a clear pedal on beat 3.

M. 11. Start again after beat 3. Phrase toward each beat.

M. 15. Hear the chord decaying and resolving to the F![]() in m. 16.

in m. 16.

M. 30. Use the last right-hand note of each measure to measure the leap.

Mm. 38–39. Play as pizzicato notes.

M. 40. Arm octaves, then use the wrist into m. 41.

M. 42. The low E is important, and lean into the right-hand octave Bs.

M. 45. Emphasize the low G![]() .

.

M. 51. The left hand crescendos into the downbeat C![]() of m. 52.

of m. 52.

M. 60. Color the C![]() in the left hand.

in the left hand.

M. 62. A special color for the C major chord.

M. 69. This measure may push faster, but m. 70 is a tempo.

M. 73. Pull back after the downbeat. Then push forward as the line descends.

M. 77. Restart after the downbeat, then push downward to m. 79.

M. 82. Broaden into the sforzando of m. 83.

M. 83. A tempo.

M. 84. A contrast of dynamics, harmony, and length of line.

Mm. 93, 95. Hear the resolutions of the chords.

M. 99. Color the chord.

Mm. 101–102. Resolve the inner line [A-G![]() ].

].

M. 108. Tempo giusto.

M. 111. Broaden this measure [before the dolce].

Mm. 121–122. Drill the arpeggio leading to the Recapitulation.

M. 125. Continue the pedal until beat 2.

M. 128. A pedal change on each chord.

M. 153. Broaden to the E![]() .

.

M. 161. Either pedal each left-hand octave or use no pedal.

M. 162. Bring out the lower line.

M. 164. Continue bringing out the lower line. And color the C![]() .

.

M. 179. Begin with only one forte. Use the second finger to lead to the left-hand octave.

Mm. 182–184. Crescendo and push forward.

Mm. 184–185. Broaden; have a strong attack for each cadence chord.

Mm. 185–186. Push forward again.

Mm. 187–188. Broaden and accent each chord.

Mm. 193–194. Maintain an even tempo. No rushing.

Mm. 197–198. Diminuendo. Each chord is an “out.”

Mvt. 2. Andante con espressione

Mm. 1–8. These are four-measure phrases.

M. 5. Shape the two-note gestures as “in-out.”

Mm. 7–8. Left hand: play legato F![]() s [play within the escapement].

s [play within the escapement].

M. 13. Shape to the E![]() in m. 14.

in m. 14.

M. 19. The right hand is all “up” arms.

M. 20. Intense upper part. No silence following this measure. Try for as much contrast between piano and pianissimo as one would between forte and piano.

M. 28. Play the first two B![]() s with the left hand.

s with the left hand.

M. 31. Pedal each left-hand octave.

M. 33. “Up” chords in the right hand.

M. 36. No silence following this measure.

M. 37. Deep sonority for the left-hand melody [D-E-F![]() -C

-C![]() ].

].

M. 38. Then the left hand plays “away.”

M. 43. Keep it moving to the downbeat of m. 44.

M. 44. The right hand plays the F![]() .

.

M. 46. Con moto.

M. 50. Legato top part. Shape the measure.

M. 56. The left hand prepares the low grace notes as a “down.” Then plays the chord as an “up.”

M. 58. Shape the motive.

M. 66. Full of pedal. Not too short on the chords.

M. 68. Shape the measure dynamically and with momentum.

M. 74. Hear beats 1 and 3 resolving.

M. 84. The accented chords are resolutions.

M. 86. Play the G![]() full of color.

full of color.

Shape four-measure phrases.

M. 1. Suspend the weight. Play very lightly.

M. 5. Touch the pedal.

M. 8. End fortissimo.

M. 19. No ritard.

Mm. 20–21. Each is pizzicato.

M. 22. A little more weight in the left-hand melody.

M. 25. Be careful with the legato slur.

M. 31. Start the measure still in piano.

M. 37. Color the B major key.

M. 42. Crescendo. Catch the bass As with the sostenuto pedal until the return in m. 48.

M. 59. An echo. Slightly slower.

M. 63. Still a richness to the tone.

M. 77, 78. Touch the pedal.

Mm. 82, 84. Take time to prepare the chord.

M. 87. Think a tiny break after beat 2 to prepare the right-hand F![]() octave.

octave.

M. 95. Prepare before the right-hand An octave.

Mm. 105–106. Touch the pedal each half measure.

Mvt. 4. Finale

M. 1. More left-hand melody for richness.

M. 7. Think a fermata over the trill. Take the first four notes of the scale with the left hand. Every note in the scale must be heard evenly.

M. 15. Play the first five notes of the scale with the left hand.

M. 16. Close the passage with a diminuendo to the D.

M. 21. Close the trill with an F![]() -G

-G![]() before the B

before the B![]() .

.

M. 22. [Pressler plays an E![]() on the last triplet.]

on the last triplet.]

M. 23. Maintain the tempo with the left-hand eighths.

M. 26. Shape the B![]() -B-A

-B-A![]() .

.

M. 28. Pedal each beat.

M. 41. Direction to the forte of m. 42.

Mm. 55–56. Very fast graces. Stay steady, not faster.

M. 71. Phrase the left hand to the low note using the thumb each time.

Mm. 76–77. Secco left hand.

M. 79. Decrescendo. Then forte.

M. 80. Right hand: have a close thumb for B-C![]() -B.

-B.

Mm. 88–89. More pedal as the crescendo begins.

M. 97. The left hand must hold the keys on the last Gs.

M. 107. A slower arpeggio [the F![]() 7 chord] for color.

7 chord] for color.

M. 111 (after 2nd ending). Play the B major chord with a strong accent in each hand.

M. 145. Pull the chord in the right hand [beat 2], emphasizing the syncopation.

Mm 164–165. Accent the left-hand chord on the second beat of each measure.

M. 166. Pull the chord [beat 2] in the left hand.

M. 169. A clean break.

Mm. 175–177. Left hand: use 1–2 for each slur.

M. 180. Close the slur as everywhere else.

Mm. 181–182. Quieter than

Mm. 179–180.

Mm. 185–186. Pesante, but no accents.

M. 194. Maintain the meter. Therefore, pulse the left-hand D![]() s.

s.

M. 195. Broaden into m. 196.

M. 197. Use the sostenuto pedal for the C![]() octave until m. 204.

octave until m. 204.

M. 225. More short pedals [beats 1 and 3].

Mm. 258–260. Make the left-hand theme clear.

M. 267. Count, in order to ritard evenly.

M. 270. Play the left-hand B-D![]() after the octave as a dotted quarter.

after the octave as a dotted quarter.

M. 272. Emphasize the low F![]() as the last note of the theme.

as the last note of the theme.

M. 280. Play the right hand as a solid chord.

Mvt. 1. Allegro con brio

M. 1. Prepare mentally. You have to know exactly the sound you want to produce. The hands must be ready.

M. 4. Come down [decrescendo] for the cello entrance, then be under the cello.

M. 9. Lean into beat 2.

M. 14. Cello, come down from F![]() to B.

to B.

M. 16. Cello, come down from G![]() to B.

to B.

M. 28. The last F![]() is a pick-up to the next measure.

is a pick-up to the next measure.

M. 29. More sound, but not faster.

M. 35. Lead with beat 4 to the downbeat.

M. 51. It doesn’t have a feeling that you have arrived. First of all, you have to rehearse it; and secondly, you have to rehearse it; and thirdly, you have to rehearse it. But after all the rehearsing is done, then you have to really play it with all your imagination and awareness.

M. 56. Piano, decrescendo with the cello.

Mm. 68–69. The piano is a continuation of the other instruments. Listen to the last note of each triplet and don’t let there be a hole between the strings and the piano.

M. 72. Cello, finish it [on beat 3], but don’t take time. Show that there’s a change of direction.

M. 74. Violin, don’t you have a staccato over that B![]() ? You have to honor it somehow, but you dishonor it.

? You have to honor it somehow, but you dishonor it.

M. 75. Without that chord, their notes don’t mean a thing. You play it so unimportant, so meaningless.

M. 77. Not slow.

M. 87. Piano, come down.

M. 91. The C![]() resolves to the B

resolves to the B![]() .

.

M. 121. No waiting for the chord, just play it so that out of B major comes G major. You go from a B top note to a G [m. 123] and to an E [m. 125].

M. 127. Loud, but only one forte.

M. 135. This, of course, is the climax.

M. 137. Same tempo. Cello, you’re playing clean and you’re playing well, but I can’t identify with your playing. More intensity.

M. 153. Not forte.

M. 176. Beat 4, not so loud. The violin has the melody.

Mm. 176–179. Violin, would you play G![]() -B the same as F

-B the same as F![]() -A and E-G

-A and E-G![]() ? Then, piano, whatever he does, you have to play that way, too.

? Then, piano, whatever he does, you have to play that way, too.

M. 195. It sounds so spastic, so jagged.

M. 214. Finish. Then begin beat 4 with a different sound.

M. 252. More left hand.

M. 254. Tranquillo, cello. It is slower; you did that. But it is also a kind of summation, so it is not a kind of vibrato that wakes up. It is a kind of vibrato that goes to bed, yes? It’s a kind of closing, a kind of summing it up after you have told the story. Piano, he needs to play off of something. He must hear your left hand. And the left hand, of course, needs the right hand.

M. 260. Cello, find time within the beat to finish the phrase. That was better, but you gave a wrong accent.

M. 262. When the violin plays that F![]() [downbeat], the piano must play a different color on that chord. It’s better, but it’s still not good. Why is it not yet good? Because you just play it and you say, “It’s not important. It’s okay.” It’s like when you drive through the country and you see a restaurant that says, “Come in just for food. It’s quick. It’s horrible, but it’s just food.” But the food that Brahms serves is for people whose taste buds are the most developed.

[downbeat], the piano must play a different color on that chord. It’s better, but it’s still not good. Why is it not yet good? Because you just play it and you say, “It’s not important. It’s okay.” It’s like when you drive through the country and you see a restaurant that says, “Come in just for food. It’s quick. It’s horrible, but it’s just food.” But the food that Brahms serves is for people whose taste buds are the most developed.

M. 264. Brahms writes a swell in the piano part. It’s not possible, but you can feel it.

Mm. 264–267. You have an F![]() , an E, a D

, an E, a D![]() , a C

, a C![]() . It’s a composed diminuendo, but he also asks for one.

. It’s a composed diminuendo, but he also asks for one.

M. 268. That’s a subito pianissimo following a little crescendo.

M. 274. Cello, I would like you to slide the last two notes. It is a diminuendo without accenting the last note. On the contrary, the last note should disappear. Basically, you should not play a ritard. You relax.

Mvt. 2. Scherzo

M. 4. Cello, go away on the last note. Piano, it is lighter. You take over from the cello. Answer in the same character.

M. 7. Piano, the left hand goes to the center of the phrase, then away.

M. 9. The first one is too loud. You are entitled to a little swell, but no heavy accents. And actually, the part you should listen to inside you is the left hand.

M. 17. Here you play second voice under the strings. And play 2-1.

M. 21. Violin, when you have the G![]() , it is less than the A.

, it is less than the A.

M. 24. Piano, on the last C![]() you play an octave in the left hand.

you play an octave in the left hand.

M. 25. Very light, very legato. It’s always two bars together, the right hand followed by the left hand. Each chord gets a pedal, but be sure that the low notes are clear.

M. 26. Play the C![]() -A

-A![]() -G with the right hand.

-G with the right hand.

Mm. 29–32. Divide the arpeggio into two hands [second ending]. The left hand takes the last three notes each time.

M. 32 (first ending). It’s a question mark, yes?

Mm. 34–35. Change the foot so that it clears up.

Mm. 36–44. Piano, the left hand is always a trumpet, yes?

M. 44. Finish on the downbeat. In the left hand the wrist plays one motion but gets two notes.

M. 48. Not a long note; don’t sit on the downbeat.

M. 60. No pedal; there are rests.

M. 64. Piano, that’s such a mess. You’re in too much of a hurry getting back up.

M. 67. The G resolves to the F![]() [m. 68].

[m. 68].

M. 77. Brahms has a pedal there, four bars, more or less.

M. 99. Piano, too loud. The strings are above you.

M. 103. For once play an F![]() instead of the E

instead of the E![]() , so you see the F

, so you see the F![]() is very special. Obviously it was done with great deliberation to get that feeling of suspense, of something that somehow asks us to be afraid for a second.

is very special. Obviously it was done with great deliberation to get that feeling of suspense, of something that somehow asks us to be afraid for a second.

Mm. 129–132. That’s so lame, like a lame duck because of 5-5-5-5. Practice the right hand alone and change the fingers.

M. 132. Here the violin finishes very softly, so the piano has to play softer still, yes?

M. 136. Close it.

M. 137. Can you play piano in the right hand and pianissimo in the left hand?

M. 138. Play the octaves molto legato. The C![]() dies down and the A [beat 2] starts where the C

dies down and the A [beat 2] starts where the C![]() has come down to.

has come down to.

M. 145. Light, light.

Mm. 152–153. Hear the difference between the major and the minor.

M. 155. Be conscious of major going to minor in the left hand.

M. 159. A maximum of piano. If he had wanted you to build up to something, he would not have had the strings come in piano [163]. Practice so that it gets lighter than that. Not fast.

M. 165. That chord, feel that your body becomes a sounding board. Is that as nice as you can play that? I hope not! This is a waltz by Brahms, and it shows that he lived in Vienna, the charm. And the left hand stays steady [Pressler sings the melody while tapping]. You heard this [the tapping]. With all the freedom I was singing, this stays steady.

M. 170. Going up takes a hair of time longer than you’re doing.

M. 173. Don’t hit the downbeat. Do you see where he starts the crescendo? That would be a good idea.

M. 178. Piano, they are not staccato. Very little space between the notes. Use some pedal. Not slower. The strings can’t connect to you and everybody goes to sleep.

M. 180. Strings, you have to respond to whatever she does. If she slows down, you must catch up the time.

M. 181. Strings, it must be beautiful.

M. 197. Piano, change the fingers in the left hand.

M. 202. Brahms gives you a decrescendo on the higher note. It’s exceptionally beautiful because the other way is ordinary. But this is special.

Mm. 203–204. The right hand sustains and gives us the illusion that you are still pedaling.

M. 210. Now you need to spread the wings. If you look at the violin part, you see he is going all the way to forte. So he needs time, and you need time. The piano part must match and become one with the violin part, yes? Can you make a legato there [on the downbeat]? I play fifth finger, and I go to the second finger just at the last second. Stretch out and make a curve with your arm there.

M. 212. These three dots under a slur—it talks in there. Then you go down and you make that last swell [downbeat, m. 214].

M. 215. Here you give the tune to the cello. Let the cello be above you, yes?

M. 217. But you play the chord [downbeat] so perfunctory. You play it, but you’re only interested in getting down there for the bass notes.

M. 219. The left hand is a tympani.

M. 227. You have to pedal in such a way that the chords in the left hand don’t disappear. All these chords are long chords. You have to be a virtuoso with your foot. You have to pedal it so that you dry it a little bit and we can hear those tympani going, yes?

Mm. 241–244. Make a line out of it. You play one measure at a time. You have to connect it with your hand, so use 5-3 or 5-4.

M. 243. You leave that to the cello. That high note is hazardous. And if he hits it clean, he gets complimented. And if he doesn’t hit it clean, you play loud and you get the compliment, yes?

M. 259. That is the last note of the phrase. Close it.

M. 434. That E is a continuation of what just happened in the strings.

Mm. 439–445. The pedal is all the way until Brahms gives you the change of the pedal, even through the rests. Make a decrescendo, not a crescendo. The arm is too heavy. A light arm floating over the keys.

Mm. 446–448. I take only the first note in the left hand and then I play everything else in the right hand. And why does it get louder when it goes up? Play very close to the keys, very close.

It’s not Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn’s are wine-drinking Alps, or champagne. These are heavier Alps, beer-drinking Alps. These are German with potatoes and sausages, but they have to be as light as they can. It’s fantastically composed.

Mvt. 3. Adagio

It is soft, illuminating, like a prayer, like a church. I think you can hear him talk to himself. It’s an innocence, as close as one can come to an audience. The middle section is more alive where the cello has that marvelous solo. And at the return, the piano is, so to speak, improvising and the strings have the melody.

M. 1. Pianissimo and loose arm. That’s too slow and has no beat. The two quarter notes go to the next measure with a very slight crescendo.

M. 4. Strings, that’s so loud and too much vibrato.

M. 8. Help it to move. The beats continue. They don’t stop.

M. 13. You play with no control of your arm. Prepare the arm, and the weight goes right into the key.

M. 15. You must hear the E. It must ring. Then it resolves to the D![]() [m. 16].

[m. 16].

M. 16. Violin, I would like that the eighth notes have more meaning. With you, they’re just a bridge to the next note.

M. 20. Piano, that’s too loud. You must take over from what they do.

Mm. 23–24. I want more sound. Emotionally, I want more.

M. 26. Strings, that’s too much vibrato! As small as possible. Very beautiful. Piano, come down. Each chord must relate to the one before it. And very legato.

M. 29. Here it’s the cello. And here it’s the violin [m. 30]. And here it’s the piano [m. 31]. But not loud, just present.

M. 33. The left hand must support.

M. 42. Now the cello goes all the way to the top.

M. 43. Close it [beat 3]. There’s no hitting. Can you lean into the piano so that you don’t hit [beat 4]?

M. 48. Piano, what are you waiting for? There’s no hole there.

M. 54. Piano, the right hand is too loud. The solo is in the violin. You just have an accompaniment.

M. 62. Cello, they play off of your downbeat.

M. 67. Piano, resolve to beat 2. And don’t hit the downbeat.

M. 69. You have to play legato. It’s not just that he has the slur, but he also uses the word. And how do we play legato? You have to phrase it. It has to be going somewhere.

M. 71. That finishes on the downbeat.

Mm. 79–80. There’s no rhythm in you. Even when you don’t play the eighths, you must feel them. Your heart should beat those eighths.

M. 90. Don’t separate so much. There’s a slur over the dots.

M. 93. Piano, let me hear the high B.

M. 95. Hear the cello A.

M. 96. Hear the violin E.

M. 97. Now hear the piano chord.

M. 98. A resolution on the B major chord.

Mvt. 4. Allegro

M. 1. Pedal is marked, but you should use very little.

M. 3. Cello, the E![]() is less than the G [m. 2].

is less than the G [m. 2].

M. 9. Piano, see how Brahms holds the left hand? He creates a sort of pedal.

M. 15. Can we be a little bit more religious and do what he asks for? It’s not that you play it too loudly, but you play it in sunlight. It should be darker.

Mm. 18–21. Piano, it sounds so staccato, like “Chopsticks.” Play it pianissimo with some pedal, and catch the left hand in the pedal. Each meas ure descends. Violin, not so ringing. Have more air in the sound. And piano, you never play the last triplet of the bar. Which sin is bigger? If it’s too loud or if it’s not played at all? For both you go to hell. I mean, you certainly won’t be invited to where Brahms is. No, you will be only invited to where the players are who don’t play him well, yes? So there is no excuse to say, “I don’t want to be too loud.” Of course, you don’t want to play too loud, but not playing the notes is not better.

M. 45. The ritardando cannot always be the same. The piano has to follow the strings, and it depends on how the phrase goes.

M. 46. With some pedal. It’s the same mood.

M. 64. Have a feeling of Appassionato. Cello, Greenhouse plays it all with up bows.

M. 87. Strings, more of a break after the first beat.

M. 101. Resolve it. The F![]() goes to G.

goes to G.

M. 106. No, it doesn’t crescendo. Just the contrary. It’s obvious, wouldn’t you agree?

M. 112. It’s one instrument divided into two.

M. 129. It’s pianissimo and sotto voce. My God, how far can this man go? All the way!

M. 142. Yes, it’s a syncopation, but you must still play it in a three.

Mm. 151–152. Not faster.

M. 184. Play the last octave with the right hand.

M. 199. Play that An [the sixth note] with the right hand.

M. 205. Con passione.

M. 241. Cello, play that D with a little accent.

M. 242. Hold the pedal all the way until the next bass note [m. 246].

Mm. 253, 261. Play these first three notes with the left hand.

M. 263. It’s only mezzo forte. There’s your forte half an hour later [m. 266].

Mm. 263, 265. Play the sixth note with the left hand.

M. 304. Start less.

M. 309. Hold back. Broaden. And then a tempo [m. 310].

Mm. 319–320. Cadence in the left hand. We need that F![]() .

.