Introduction

Today, workplaces are increasingly culturally diverse, and managers and employees interact across various societal cultures. Facilitating communication and cooperation among individuals to accomplish shared goals is central to leadership, and multicultural workplaces represent new challenges and opportunities in this regard. This chapter proposes values work as a strategy, inquiring into the implicit ideas of good and bad leadership at the multicultural workplace with loosely held cultural categories. The aim of the chapter is to examine the factors that shape managers’ and employees’ implicit ideas of leadership and to analyse how leadership is negotiated in everyday interaction across cultures. Three nursing homes in Oslo, Norway, are the empirical context of the case study.

A Critical Review of the Comparative Paradigm of Cultural Universals

The relevance of culture to leadership is well established, especially through large-scale studies that have developed cultural universals or dimensions for comparing cultures at the societal level (Hofstede, 2001; House, 2004). In much of cross-cultural management research, these cultural dimensions are strongly linked to values (Hofstede, 2001; House, 2004; Mustafa & Lines, 2016). In the GLOBE project (House, 2004), the dimensions developed to measure and compare societal culture are referred to as values orientations. In the same vein, Mustafa and Lines (2016) reviewed the literature on culture and leadership and analysed the interaction between societal level values and individual values. However, this approach in cross-cultural management—identifying culture with values—has been criticised for ignoring other aspects of culture that frame leadership practice, such as societal structures and legal frameworks (Alvesson, 1989; Nathan, 2015).

A theoretical concept that describes the relationship between societal culture and leadership in the comparative tradition, and in the GLOBE project in particular (House, 2004), is ‘culturally endorsed implicit leadership theories’ (CLTs). The central tenant of implicit leadership theory is that managers and employees bring to their daily interactions implicit, taken-for-granted ideas of good and bad leadership (Eden & Leviatan, 1975). Building on implicit leadership theory, the GLOBE project aimed at extending the theory from an individual level to a societal level, arguing that implicit ideas of leadership are culturally contingent and culturally endorsed (CLT). To gain acceptance and support from employees, managers must therefore take culture into account and behave in a manner that matches the culturally contingent expectations of the specific society. CLT can then be identified and measured at the societal level and compared with those of other societies. This theory of culturally congruent leadership has gained broad support within cross-cultural management research (Green, 2017; Mustafa & Lines, 2016); however, it has also been criticised for promoting a static and essentialist understanding of culture (Fang, 2005; Mahadevan, 2017; Nathan, 2015).

Phenomena like globalisation and migration make cultural configurations more complex and blur the lines that mark the societal level. Macro-level comparative approaches in cross-cultural management have been criticised for offering a perspective on culture that does not align with the reality of today’s multicultural workplaces. Further, the use of cultural universals to sensitise individuals to cultural differences has been criticised for reinforcing stereotypes and essentialising aspects of people’s social identities (Nathan, 2015; Witte, 2012). This is why researchers have called for alternative, in-depth qualitative approaches that analyse the complexity of leadership and culture in multicultural environments (Fang, 2005; Mahadevan, 2017).

In line with this criticism, this study argues that the macro-level comparative approach to culture and leadership offers a flawed perspective on the interplay of culture and leadership at the workplace. The approach is too narrow in that culture is reduced to values, and it is too broad when culture is identified at the societal level. To understand culture and leadership at the multicultural workplace, it is necessary to broaden the gaze, beyond values, to include the larger institutional context and to narrow the gaze to inspect more specific local organisational factors.

Exploring Implicit Ideas of Leadership at the Multicultural Workplace

Through a case study in three nursing homes in Oslo (Norway), this study explores implicit ideas of leadership at the multicultural workplace and the different sources that shape these ideas. In line with practice theory (Nicolini, 2012) and the ‘Leadership-as-practice’ tradition (Raelin, 2016), this study locates leadership in the practice as it unfolds at the workplace. The study analyses how leadership is negotiated in the everyday interactions of managers and employees. Such negotiation involves an exchange of ideas of good and bad leadership to arrive at a common frame of understanding (Børve, 2008, p. 17) as well as specific leadership practices (Børve, 2010).

The present study seeks to analyse culture in a way that does not confine it to societal or national boundaries. Culture is a social phenomenon enacted at different levels: societal, organisational and group (Mahadevan, 2017). Culture is tied to collectives and as such draws boundaries between insiders and outsiders (Borofsky, 1994). But contrary to the comparative paradigm described above, the boundaries are multiple, shifting, incongruent and overlapping. Thus, although culture is a collective phenomenon, it is enacted by individuals embedded in a variety of cultural contexts and belonging to several different cultural collectives simultaneously.

The present study draws on elements from the GLOBE project, particularly the concept of CLTs, but seeks to use the concept differently. Implicit leadership theory provides a useful framework for understanding how managers and employees negotiate leadership at the workplace, but the cultural configuration of organisational members at the multicultural workplace is more complex than what is suggested by the GLOBE project. Organisational actors embody unique cultural configurations that vary for instance with their first-, second- and third-generation country background and the time spent in their current country of residence. Other collective identities like gender and profession add to their individual cultural configurations (Witte, 2012). In this chapter, I argue that these dynamic cultural configurations play a central role in shaping the implicit ideas of leadership and that to improve communication and cooperation at the workplace, it is more fruitful to inquire into these than look for societal level scores to measure them.

Applying an institutional perspective, this study broadens the understanding of culture beyond values and identifies different contextual factors that shape the implicit ideas of leadership at the multicultural workplace. Contextual factors can be found at the institutional, field and organisational levels (Scott, 2014). For instance, factors at the institutional level include legal frameworks and regulations like the Working Environment Act and the Basic Agreement between trade unions and the employers’ unions (Børve & Kvande, 2018; Byrkjeflot, 2001). These frameworks and regulations are central to the Norwegian culture; they frame leadership practice and regulate the roles, rights and responsibilities of managers and employees. At the field level, characteristics of the healthcare sector and the professions dominating the sector are contextual factors that frame leadership practice (Zilber, 2012). In addition, the formal and informal as well as technical and ideational features specific to an organisational context (Scott & Davis, 2016) are important for understanding leadership in a local setting.

Research Design and Methods

To explore the implicit ideas of leadership and the negotiation of leadership at the multicultural workplace, a qualitative approach was chosen, and three nursing homes in Oslo were selected for a case study (Stake, 1995). In the Norwegian context, nursing homes represent highly multicultural workplaces. In this study, the share of employees with an immigrant background varied from 69 to 84% of employees on permanent contracts in the units studied. To investigate the complex cultural dynamics of leadership in the nursing homes, I studied one unit with a manager from an immigrant background and one unit with a manager from the majority background in each nursing home.

List of interviewees

Name | Regional background | Position | Nursing home |

|---|---|---|---|

Anita (f) | Norway | Care assistant | Marigold |

Banu (f) | Asia | Unit manager | Riverside |

Bente (f) | Norway | Healthcare worker | Riverside |

Celeste (f) | South America | Care assistant | Marigold |

Dragan (m) | Eastern Europe | Unit manager | Cornerstone |

Edel (f) | Norway | Healthcare worker | Cornerstone |

Ellen (f) | Norway | CEO | Cornerstone |

Faiza (f) | Africa | Care assistant | Cornerstone |

Hamza (m) | Africa | Care assistant | Cornerstone |

Harald (m) | Norway | CEO | Riverside |

Hege (f) | Norway | CEO | Marigold |

Hilde (f) | Norway | Unit manager | Marigold |

Ingrid (f) | Norway | Nurse | Marigold |

Jenny (f) | Asia | Nurse | Marigold |

Jodit (f) | Africa | Healthcare worker | Marigold |

Jonathan (m) | Africa | Unit manager | Marigold |

Justyna (f) | Eastern Europe | Nurse | Cornerstone |

Kari (f) | Norway | Unit manager | Cornerstone |

Kristin (f) | Norway | Unit manager | Riverside |

Marko (m) | Eastern Europe | Nurse | Marigold |

Milan (m) | Norway/South America | Nurse | Riverside |

Nina (f) | Norway | Healthcare worker | Riverside |

Omar (m) | Africa | Healthcare worker | Riverside |

Shanti (f) | Asia | Healthcare worker | Riverside |

Silje (f) | Norway | Healthcare worker | Cornerstone |

Vanessa (f) | Asia | Nurse | Cornerstone |

Zahra (f) | Asia | Nurse | Riverside |

NVivo was used for thematic coding and analysis of field notes and interview transcripts. The notes from the semi-structured shadowing were coded and analysed in accordance with procedures from previous studies (Askeland, 2015). As recommended for case studies, the different types of data were converged and analysed as a whole (Yazan, 2015). After a preliminary analysis of the data from observation and interviews, findings were shared and validated at meetings in the nursing homes. In terms of transferability of the results, the choice of nursing homes has both advantages and limitations. As mentioned, nursing homes have a high percentage of managers and employees with an immigrant background, which provided rich opportunities to observe negotiation of leadership across cultures. On the other hand, choosing workplaces where employees with an immigrant background are in minority could generate different results showing a more dominant influence of the Norwegian cultural context.

Implicit Ideas of Leadership at the Multicultural Workplace

The following sections present findings from the fieldwork and interviews. It starts with a presentation of the implicit ideas of leadership in the nursing homes, followed by an analysis of the multiple sources of these ideas: contextual factors and individual experiences. The three managers with an immigrant background are then presented as examples of how leadership is negotiated at the multicultural workplace.

Implicit Ideas of Good and Bad Leadership in the Nursing Homes

Descriptions of good and bad leadership

Good leadership |

• The leader must be available and visible in the unit • The leader must listen to the employees • The leader must show some flexibility • The leader must support the staff and show that they fight for the staff • The leader must call in substitutes when someone is sick • A good leader puts on the uniform and isn’t afraid of working • A good leader gives you a pat on the shoulder. It is someone who says you have done a good job today • A good leader is strict and kind—a good mix of both |

Bad leadership |

• Bad leaders lock themselves in the office and just sit there; they are not present in the unit • Bad leaders only think of money and budget • Bad leaders are very rigid and closed • Bad leaders are strict with their employees but pander to their bosses |

Contextual Factors and Individual Experiences as Sources of Implicit Ideas of Leadership

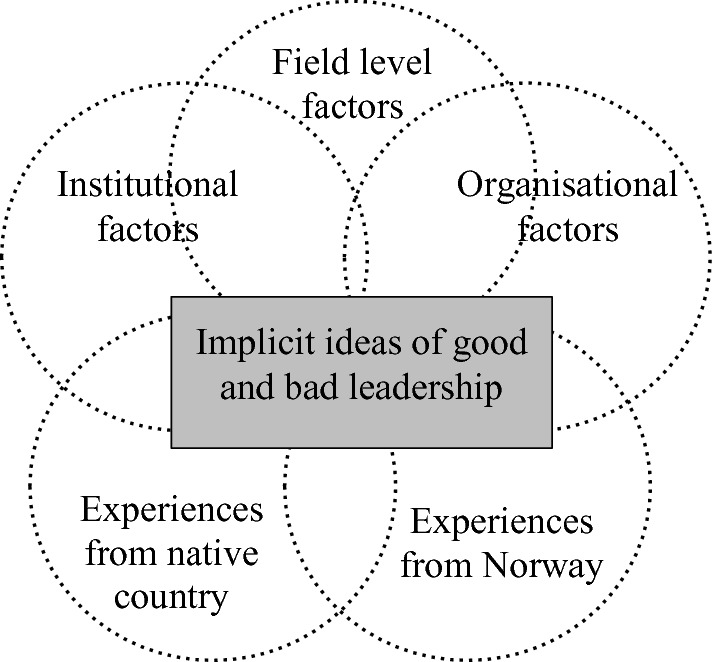

Where do the ideas of good and bad leadership come from? From the data, two sets of sources were identified: contextual factors from the institutional, field and organisational levels and individual experiences of leadership from the country of origin and the country of residence.

We work under the same rules and the same obligations, you know. And rights. (…) We have the same rights all of us, and the same obligations. So that doesn’t worry me. (Omar, health care worker at Riverside)

Jonathan [unit manager at Marigold] follows the Norwegian rules. If he doesn’t, we can complain. (Alvin, health care worker at Marigold)

Employees expected leaders to play by the rules and were conscious of the mechanisms that protected them and regulated the power balance between managers and employees.

The shadowing of the six unit managers showed that being unit managers in a nursing home shaped the manager role in a significant way, which can be attributed to nursing homes as a sector or institutional field. The unit managers engaged in similar types of activities (e.g. supervising clinical work, staffing shifts, attending meetings, responding to emails and phone calls), and they related to the same set of actors (CEOs, other unit managers, employees, residents, relatives of the residents). One of the factors that featured in the list of good leadership was appointing substitutes to compensate for employees on sick leave. Again, the use of substitutes may be attributed to the field level as the healthcare sector is characterised by a relatively high percentage of employees on sick leave, and the completion of tasks depends on the number of hands available. The topic of sick leave and use of substitutes was discussed frequently among the employees.

Organisational factors seemed to cause differences in the patterns of leadership between the unit managers. Tasks included in the job description and access to office space were two examples of such organisational factors. Among the unit managers, the access to a separate office space was not consistent. Jonathan and Hilde at Marigold had their own offices on one floor, while their units were located on other floors. At Riverside, Banu and Kristin did not have a separate office space. For administrative work, they used the computer at the staff room that was accessed by all staff members. At Cornerstone, Dragan and Kari had private office spaces next to the staff room in their units. The physical conditions of the space where the unit managers spent time during the day influenced how they interacted with the employees and thus the employees’ expectations towards their managers.

The tasks included in the unit managers’ role descriptions varied between the nursing homes. While all the unit managers were trained as nurses, the extent to which they were expected to participate in the daily care of residents varied. At Marigold, unit managers did not participate in care on a regular basis, but when needed, they would put on the uniform and share the tasks with other employees. At Riverside, Banu and Kristin were counted as part of the staff in care on a regular basis. Since they also had other responsibilities, they often took on the lighter cases or dropped out to attend to other commitments. At Cornerstone, the unit managers participated in care once a week. These differences implied that Banu and Kristin at Riverside wore the uniform at all times, whereas the unit managers at Marigold and Cornerstone wore regular clothes and changed into the uniform only when they participated in care. The degree to which managers and employees share the same tasks and wear the same clothes influences expectations towards leadership practices and the implicit ideas of good and bad leadership. I perceived that unit managers at Riverside, who participated in care on a daily basis and wore the same uniform as other employees, were expected to behave in a more egalitarian way than managers in the other nursing homes.

In [my country in Eastern Europe], leaders decide everything. There is no room for communication so … they are dictators. Employees do what the leader says, and the leader has absolute power” (Dragan, unit manager at Cornerstone)

[In my country in Asia] it is something about how they have this great respect for their leaders, that when the leader says it has to be done, they do it. For they are a bit afraid of being punished, you know. For there are consequences. (…) It’s good in a way. Like a bit authoritarian. (Vanessa, nurse at Cornerstone)

In [my country in Southern Europe] you only speak with your leader if there is a problem – something that you cannot solve. You may not even know your leader. (Magdalena, nurse at Marigold)

Although the descriptions of leaders given by employees of different country backgrounds seemed unanimous, they should not be perceived as specific descriptions of leadership in the respective countries. The descriptions were relative—comparing leadership in their country with what they experienced in their Norwegian work context. In the data, there were fewer references to typical Norwegian leadership, but aspects like a flat structure and the approachability of the Norwegian managers stood out. A key factor in the conversations with employees from an immigrant background was that they continuously related to both the culture of their native country and that of their present work country (Norway).

Here, it is the employees who manage the boss. It is “my way or the highway”. The smallest thing, and the employees write a deviation report on their leader. “I am protected because I am an employee”. Here it is the Working Environment Act and all that stuff.

These examples show that employees were not uncritically socialised into the Norwegian context. They did not simply accept what was considered typical Norwegian leadership as good leadership.

Sources of implicit ideas of good and bad leadership

Negotiating Leadership in the Nursing Homes

To illustrate how leadership is negotiated at the multicultural workplace, the three managers with an immigrant background are presented as examples.

Jonathan (Marigold). Jonathan, from a West African country, had studied nursing in Norway. He had no formal management training when he took over as unit manager about two years prior to the field study. When he took over, the employees in his unit were on sick leave on average 28% of their regular working hours. His major achievement as a unit manager was to reduce this percentage to below 6%. Jonathan, the staff and the CEO at Marigold, attributed this achievement to his leadership style and especially to his visibility in the unit and his flexibility in accommodating the needs of the staff. Jonathan spent little time in the office doing administrative work. Once or twice a week, he stayed back after normal work hours to complete his administrative tasks. Jonathan preferred informal areas for interacting with the staff—the hallway, the kitchen or the resident rooms where he accompanied the staff. When employees asked for changes in their shift schedules, Jonathan tried his best to accommodate. The employees found him understanding and easy to talk with, and he claimed he made an effort to be so. He said that at times, he felt like a social worker but added that the give-and-take was a part of the game: ‘If you show them that in case of sick leave, you call in substitutes, within reasonable limits, it works’. When the staff sensed that he made an effort to cover shifts with substitutes, they made an extra effort to not fail him. Overall, Jonathan responded to the core aspects of the implicit ideas of good leadership in the nursing home and was appreciated and respected for it.

She is a bit direct. And it is not everybody who likes that. You feel that you are treated very hard sometimes. Nobody likes to be treated badly. Everybody does their best, and still they get “pepper”. (…) And then we have heard she is the best to save money. So, it means that she doesn’t spend money on calling in substitutes. (Zahra, nurse at Riverside)

When analysed in the context of the implicit ideas of leadership, Banu failed to live up to core expectations of leaders: to be understanding, to remain loyal to employees and to communicate in a soft and kind manner. Her strengths—being performance-oriented, strategy-driven and a visionary—did not align with the leadership characteristics highlighted in the implicit ideas of leadership in the nursing homes; as a result, she did not earn legitimacy or support from the staff. Banu argued that as a leader, she could not expect to receive positive feedback from the employees. The support from the CEO and positive comments from residents and their relatives were more important to her. In a way, it seemed like she had resigned from negotiating leadership with her employees, and the level of conflict with the staff in the unit was high.

They are not used to direct feedback. They mean I should wrap it more in and say it in a nice way. No one likes to receive criticism, even if it is constructive. (…) My job is to correct the mistakes and supervise the employees so that they don’t make mistakes. So, I need to have this kind of … a bit direct leadership. (…) I need to become dictator as long as we have serious mistakes.

The autocratic tendency was in sharp contrast to what was perceived as good leadership in the nursing homes. So how did Dragan get away with it and receive high scores on the employee survey? It appears that Dragan had special ways of demonstrating affection towards his employees. The employees used emotionally charged words when expressing how much they liked him. Alvin, a healthcare worker from Asia, captured the tension between the affective attachment and Dragan’s directness: ‘It is kind of like a father. We are the children and get scolded by our father. We are like a family’. Alvin seemed very satisfied with this style. By developing an affective relationship with the staff and creating a family spirit among the employees, Dragan created a space for himself to be direct and, at times, autocratic. Thus, he responded to the core aspects of ideas of good leadership in the nursing home but also renegotiated them to create acceptance for his more authoritarian leadership practices.

How did culture influence the three managers’ negotiation of leadership? Interestingly, all of them clearly distanced themselves from the leadership practices in their country of origin and frequently cited ideas of leadership that they had adopted in the Norwegian study or work context. However, they also deliberately drew on their cultural background as a resource. Dragan specifically noted how his temperament as an Eastern European was different from that of the typical Norwegian and allowed him to connect with the more emotional and expressive temperaments of his employees from around the world. When Jonathan handled permission requests from employees who wanted to visit their home country to care for their family members, he drew on his personal experiences with a sick mother in West Africa and his family members who expected him there. Some employees linked their managers’ leadership practices to their country backgrounds even though the managers’ self-perceptions indicated otherwise. Other employees argued that it had more to do with the manager’s personality.

The examples of the three unit managers show that it is difficult to isolate cultural values from their country of origin or country of residence as factors determining leadership practices. Contextual factors from the institutional environment, the field and the organisation, as presented above, framed their leadership practices. As such, the unit managers drew on a repertoire of resources in their leadership practices. These resources may be traced back to the culture of their country of origin and to the Norwegian context, but also to professional background or leadership discourses that transcend national boundaries.

Concluding Remarks

To enhance communication and cooperation at the multicultural workplace, it is necessary to actively engage with culture and leadership. This study proposes values work as a strategy—inquiring into the implicit ideas of leadership, taking into consideration the dynamic cultural configuration of the organisational members. The study has shown that contextual factors at the institutional, field and organisational levels frame leadership in a significant way. The contextual factors, such as the legal framework, office space and job descriptions, are more than technicalities. They come with sets of value-laden expectations that shape the implicit ideas of leadership and needs to be discussed. The process of values work also requires a space for sharing individual experiences of leadership across cultures, as these experiences as well frame implicit ideas of leadership. Through values work, managers and employees at the multicultural workplace make their implicit ideas of leadership explicit in a continuous dialogue around legitimate expectations of leaders and employees. The degree to which managers and employees respond to implicit ideas of leadership in a meaningful way impacts communication and cooperation.

The comparative paradigm in cross-cultural management has focused on national or societal level culture scores on values dimensions (Hofstede, 2001; House, 2004). The present study has shown that these scores fall short for two reasons. First, when culture is limited to values, the influence of contextual factors arising from the institutional environment, the field or the organisation is omitted. Second, societal culture scores do not capture the heterogeneity of cultural influence at the multicultural workplace. Hence, this study argues that it is necessary to broaden the perspective—to zoom out—to include the broader institutional context. At the same time, it is also necessary to zoom into include the factors specific to the local organisation. Instead of trying to identify cultural universals, which may reinforce stereotypes and stigmatise organisational actors, it seems more useful to examine the implicit ideas of leadership with loosely held cultural categories.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.