CHAPTER FOURTEEN

DAY 401

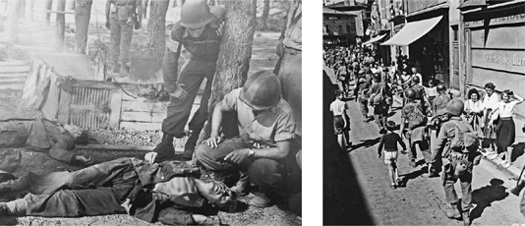

(LEFT) Dead German soldiers lie near a machine-gun emplacement, St. Maxime, France, August 16, 1944. [National Archives]

(RIGHT) Thunderbirds from the 157th Infantry Regiment greeted by citizens in Bourg, southern France. [National Archives]

THE RED LIGHT WAS ON. Major General Robert Frederick stood anxiously at the door of the C-47 plane, waiting for the green “GO” light to flash on. His standard-issue paratrooper watch showed the second hand ticking toward 4:40 A.M. He had a .45 on his hip, a white silk scarf at his neck, and a blue flashlight in his hand for signaling once he was on the ground. The plane’s engines roared. At 4:40 A.M. precisely, the green light flashed on.

“All right, fellows, follow me,” said Frederick.

Chutes soon filled the skies above southern France as five thousand Allied troops floated through the darkness. Frederick shook with fear as he dropped through thick fog. Then the ground rushed up to meet him. He landed badly, colliding against a wall. A ten-inch scar from an old wound opened up. He cut a piece of cord from his parachute and used it as a tourniquet to stop blood from running down his leg into his boots. Then he looked around for other parachutes but didn’t see any. Perhaps he had jumped too soon. He pulled out a map and turned on his flashlight. In its blue glow, he tried to figure out where he had landed.

Frederick set off into the darkness. He had gone perhaps fifty yards when he saw what he thought was a German in the early-morning mist. He crept behind the man and then leapt onto him, grabbing him by the throat.

“Jesus Christ!” blurted the man in a thick English accent.

Frederick relaxed his hold. The man belonged to his First Airborne Task Force.

“Who are you?” asked Frederick.

“I’m from the Second British Independent Parachute Brigade.”

The paratrooper was as lost as Frederick.

“You’d better be careful. Your helmet in this mist looks like it’s German.”

Frederick was anxious to link up with others in his unit, code-named Rugby Force, which had jumped into the Argens Valley between the towns of Le Luc and Le Muy. It was critical to secure the valley and prevent the Germans from counterattacking through it. To the south, beyond a range of hills, lay Operation Dragoon’s landing beaches near St. Raphael and St. Tropez. The Germans must be denied control of the heights at all costs if the Allies were to avoid heavy casualties as they came ashore.

SPARKS AND HIS men, among fifty thousand VI Corps troops scheduled to land on August 15, crouched down in landing craft as they moved through a haze of gunpowder smoke that clung to the water. They were headed toward a beach near St. Maxime on the Côte d’Azur. There was thick cloud cover. Conditions were perfect for an invasion.

Will I be alive or dead by tonight? wondered BAR carrier Bill Lyford.

A nineteen-year-old held up his sixty-pound flamethrower and called to a friend.

“Hey, Joe. How do you like your Germans, rare or well done?”

For some of the men, it was their fourth D-day.

“Hell,” said one grizzled veteran, “I’ve been on more boats than half the guys in the Navy.”

Watching the VI Corps’s landing was Prime Minister Winston Churchill. He had fiercely opposed Operation Dragoon, as had Mark Clark, both arguing that it would divert resources from Italy, where the campaign to defeat the Germans dragged on. But now a delighted and excited Churchill chomped on his cigar on board the destroyer Kimberley, looking through his field glasses as the first wave prepared to hit the beaches.

There was surprisingly little resistance as the Thunderbirds landed on the sands of St. Maxime. Massive naval bombardment and General Frederick and his men had made sure of that. “The best invasion I ever attended” was how Bill Mauldin, now working for the Stars and Stripes, described the landings in southern France, the most successful of the entire war. Not one man from the regiment was killed. Just seven were wounded as they took cover from halfhearted mortar fire and the odd machine-gun burst. By lunchtime Germans were surrendering in droves, filing down from the hillsides before being herded onto the beaches.

That afternoon, as Sparks and his men pushed inland, a Frenchwoman rushed from her house. “From the woman came a torrent of rusty English,” remembered Jack Hallowell, “most of which added up to: ‘Where in hell you been? We been waiting years for you.’ ” It was the beginning of what one journalist, welcomed by a waiter carrying a tray stacked with flutes of champagne, would call the Champagne Campaign—a heady advance north from the French Riviera past some of the world’s finest vineyards. Fresh flowers were thrown in the Thunderbirds’ path, and petals clung to their dusty boots. For the first time, they were truly greeted as liberators. Young women embraced them, planting wet kisses on their cheeks, and presented vintages carefully hidden from the beastly Boche. On they marched beneath parasol pines, feeling the warm sun of the Riviera beating down on their faces, admiring the brightly painted buildings, inhaling the balmy evening air perfumed with mimosa and jasmine.

Sparks’s command post that first night in France was in the bucolic village of Plan de la Tour, five miles inland: a very good gain, he felt, for his first day in France. He was delighted his men had gotten off the beach so quickly. The casualty rate had been less than 1 percent rather than the 20 percent predicted. The enemy might be running out of troops, he figured, and could no longer fight effectively on so many fronts.

SPARKS WAS RIGHT. The Germans had expected the landings, but Hitler had not been able to reinforce his Army Group G in southern France, which comprised eleven under-equipped infantry divisions and a badly depleted armored division. He needed every man he could find to hold back the Russians in the east and the Allies in northern France.

In Russia, Operation Bagration had, since June 22, dealt a serious body blow to the Wehrmacht. Two million Red Army soldiers, backed by almost three thousand tanks, had inflicted more than four hundred thousand German casualties—a quarter of Hitler’s manpower in the east. Fifty thousand captured German troops were paraded in a rapid march through Moscow that lasted ninety minutes before all the humiliated had passed by. In a symbolic gesture, the Soviets washed down the streets after the defeated fascists had been escorted back to POW camps, where most would not survive the war. As Sparks snatched a few hours’ sleep for the first time in France, on his 401st night of war, Hitler’s forces in Russia were now in full retreat, forced back to a line along the Vistula, just four hundred miles from Berlin, with only the Oder River serving as a natural obstacle to the Red Army’s accelerating advance.

In the south of France, where Sparks and his men would begin the push north just after dawn, Hitler’s forces were also living on borrowed time, fugitives from the law of averages, outnumbered in men and in tanks by four to one. To the north, they were also on the run. Eisenhower’s armies had finally broken out of Normandy after brutal fighting around St. Lô and Caen and were now barreling toward Paris, having taken two hundred thousand prisoners, many from Hitler’s finest Panzer divisions. Beyond Paris lay the last great prize—Berlin. No wonder Hitler called the day Sparks arrived in France the worst of his life.