CHAPTER SIXTEEN

THE VOSGES

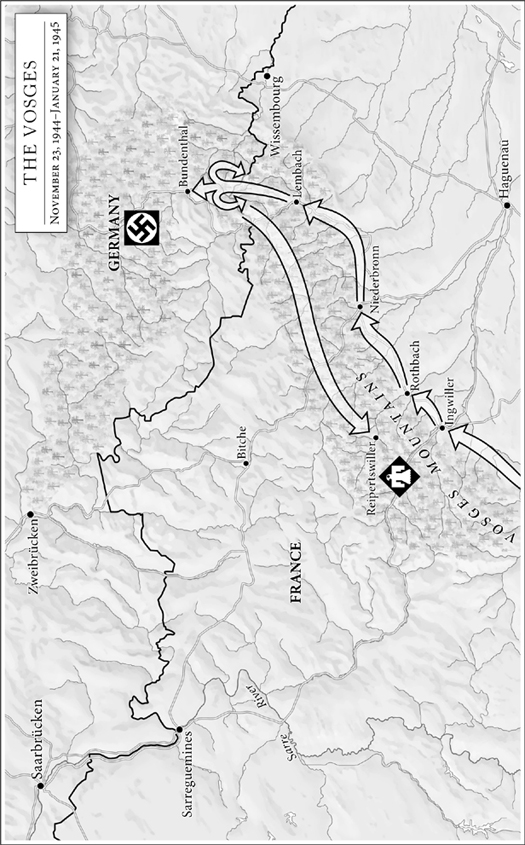

Thunderbirds in the Vosges mountains, 1944. [National Archives]

THE MOSELLE RIVER SURGED, high with autumn rains, through the gorges and past the vineyards with their ripe white grapes. Where it crossed through the medieval fortress town of Epinal, at the base of the forested Vosges mountains, the Germans dug in. They blew the stone bridges, mounted machine guns on the northern banks, and then waited to start mowing down Americans.

On September 21, the Thunderbirds attempted to cross the fast-flowing Moselle at Epinal, less than a hundred miles from the German border. All three regiments managed to get across the river, despite its eighty-foot span with steep banks rising twenty feet high in some places. But they suffered heavy casualties. One company lost a fifth of its men. The bloody crossing marked a milestone: The Thunderbirds were now midway between the beaches of France and Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. A signpost was placed on a pontoon bridge across the Moselle with arrows pointing in both directions and reading: ST. TROPEZ, 430 MILES; BERLIN, 430 MILES. Sparks had traveled farther in six weeks than he had in almost a year of war in Italy.

Beyond Epinal, he pushed his Third Battalion into the Vosges, mountains thought to be insurmountable in winter, where progress meant mastering a new form of warfare as intense as anything experienced in the dense jungles of the Pacific. The enemy could be inches away and a man would not know it, so closely bunched were the pines trees and so thick were the fogs and mists that clung to the valley floors that fall. “You saw men get killed right beside you every day,” recalled G Company’s George Courlas. “You soon realized your life was going to be very short.”

The thick forests aroused primeval fears in the least superstitious. Scouts could expect to be fired on at any moment. The mere snapping of a twig underfoot could cost a man his life. It took immense sangfroid, nerves of iron, to creep up on enemy positions, footsteps soft in the pine needles beneath towering fir trees. Without a compass, men would get lost for days. Every tree was a possible German strongpoint and every bush could shield a machine gun. “It was sometimes a relief to be fired on,” recalled one man, “for fire gave away the location of the enemy.”

Others became so tightly wound that they jumped and opened fire at the slightest sound. Men felt they were being watched at all times. They kept their bayonets sharp just in case the next bush, shrouded in mist, suddenly leapt to life. Raindrops sounded uncannily like footsteps, the steady dripping from branches making it seem as if the enemy was creeping closer and closer. At night, the darkness was total. Men could not even see their hands.

Silence was essential to staying alive. Officers and platoon leaders sometimes dared not speak or even whisper commands. It was safest to gesture and blow signals into a field telephone to direct supporting fire. But often it didn’t matter how quietly men moved in the trees, whose lower boughs sometimes touched the ground. The enemy would dig in, cover their holes, wait for Americans to creep past, then jump up and fire at them from behind. “You had to get right on top of the goddamn Germans before you got into a firefight,” remembered Sparks. “We took more small arms casualties than any other place because it was very close fighting.”

Nazi ingenuity and subterfuge reached new heights. One day, a patrol spotted Germans wearing American uniforms and carrying M1 rifles as they booby-trapped a woodpile. The latest latrine joke was that the “Krauts” had stopped surrendering because Americans had started feeding prisoners C rations. Instead, the enemy retreated just far enough to regroup and strike back like a coiled snake. They never failed to leave death hidden in their wake, burying mines and then running over them in tracked vehicles before arming them, so that Sparks’s men would see the fresh tracks and assume the roads were safe.

The fir trees, stretching toward the Fatherland, were as lethal as the mines. Artillery fire exploding in their upper branches had a devastating effect on any man cowering in an uncovered foxhole below. Shell fragments and jagged pieces of wood showered down, splitting skulls wide open. The best protection was to stand upright against a tree, exposing only shoulders and helmet, but few had the composure to do so, and instead most flung themselves instinctively to the ground.

Men sometimes had to cross open pastures dotted with dead cows to reach the trees, from which snipers wrapped in camouflaged capes often fired. If Thunderbirds were spotted in the open, just a few seconds might pass before they heard the terrifying sounds of a multiple rocket launcher, the Nebelwerfer. It was as if women far in the distance were sobbing their hearts out, then the moaning would grow louder and louder, becoming a banshee-like scream. After a heart-stopping silence, six-inch mortar bombs would land with a deafening racket, spraying shards of metal in every direction.

The unrelenting stress was too much for many men. Even the seemingly unflappable began to break. Stranded one day in a field as bullets cracked a few inches above his head, twenty-year-old Clarence Schmitt, who had been with the regiment a year, realized that his nerves had “snapped”: “I’d been one of the lucky bastards who’d never been hit. I just couldn’t take any more.”

Schmitt ran back to a sergeant in his company.

“I can’t take this shit no more.”

The sergeant was busy dealing with a sane but terrified private.

“Get your fucking ass back up there,” the sergeant shouted at the private.

Then he pointed to Schmitt.

“Can’t you see? My men are going crazy.”

IT DIDN’T MATTER what rank men were, how tough their upbringing, how calm they appeared before others, when the German 88s began to seed every square yard with lethal shards of hot steel that cauterized as they ripped through flesh. Everyone’s nerves snapped sooner or later. According to the U.S. Army surgeon general, all men in rifle battalions became psychiatric casualties after two hundred days in combat. “There aren’t any iron men,” declared one army psychiatrist. “The strongest personality, subjected to sufficient stress over a sufficient length of time, is going to disintegrate.”

The all-important infantrymen, the only forces that could actually defeat Nazism on the ground, comprised just 14 percent of the U.S. Army’s overseas numbers. But they suffered three-quarters of its casualties that fall in Europe, with well over a hundred thousand men already pulled off the line for “psychoneurotic” reasons, one of the official euphemisms for combat fatigue. Before they went crazy, more and more young Americans chose to go AWOL. Officially, eighteen thousand American deserters now roamed behind the lines, desperate for the war to end before they got caught and sent back to the front.

The incidence of self-inflicted wounds soared. In the trade-off between life and a big toe, there was no contest. Guy Prestia, in the regiment’s E Company, had carried a machine gun all the way from Sicily. He joked with one man in his unit about the man’s failure to shoot off his toe. He had kept his boot on and shot himself in the foot, but the bullet had gone between his big toe and the next one. Others were smarter and did it right. They took a loaf of bread and put it on their foot so that when they fired there would be no powder trace. That way, they got away with it.

Most Thunderbirds carried on until they couldn’t go a step farther and then suddenly collapsed. One night, Sparks came across a soldier sitting beside a trail through thick woods. The man was crying.

“What’s the matter, soldier?” asked Sparks.

When the man didn’t reply, Sparks knelt down beside him. Close up, he recognized him. He was one of his company commanders. He had been in combat for more than a year.

Sparks turned to the men beside him.

“Take the captain back to the aid station and you tell the doctor I want this man evacuated permanently. He’s not to come back.”

Yet another of Sparks’s men had finally reached his limit. “You get pounded enough, you’re going to break,” recalled another of them, Private First Class Adam Przychocki, who had also lived on borrowed time until he too was treated in an evacuation hospital for combat fatigue after enduring one too many bombardments.

How long would his men last, Sparks wondered, in the face of death, with a determined enemy trying to kill them every minute of every day? Few believed they would survive to see the defeat of Nazi Germany, let alone their families back in America. Yet they kept fighting, carrying out his every command like automatons, no questions asked. They were exactly the kind of soldiers the army wanted: dedicated, hardened, professional killers.

Staying as numb as possible yet still being able to fight was crucial. After Anzio, Sparks had learned how vital it was to cut himself off from his emotions, to stay detached, if he was going to continue to function effectively as a leader. It was all about minimizing pain. He had seen men in foxholes in Italy who understood that if they left their frozen feet alone they would suffer less. If you rubbed them, tried to reanimate them to bring feeling back, you would soon be in agony, unable to stagger down the mountain. You’d have to be carried. No one wanted that.

So long as he stayed numb, Sparks could fight. He could stay sane. He had stopped worrying about getting killed. Only the letters and photos from Mary, the glimpses at her and Kirk in the photos he had placed under Perspex on the butt of his lucky Colt .45, reminded him to care whether he lived or died.

SPARKS AND HIS men had arrived in the Alsace-Lorraine region of northeastern France. Many of the signs on roadways here bore German names. Some locals were taciturn and surly, waving halfheartedly at their liberators: It was a far cry from the beaming and joyous French farther south. Many communities had both German and French loyalties, in a region that had passed back and forth between the two countries several times in the last century.

A machine gun snarled. Another joined in. Then there was the hollow sound of German mortars firing, followed by explosions that ripped across a wooded hill. Soon came the whistle and whine of artillery shells. Alarmed by radio reports from his rifle platoons, Sparks set out from his forward command post to join his men who had come under fire. As he crossed an open field, machine-gun bullets snapped overhead. He dived to the ground, crawled back to a radio operator, and called regimental headquarters for reinforcements. When he looked up, he saw a column of half-tracks and a group of tanks in the distance, moving toward him. He was in the open, pinned down with no way to escape.

Sparks began to prepare for the worst—until he noticed that the soldiers in the half-tracks were wearing long woolen coats. He had seen such overcoats before in Italy. To his immense relief, he realized they belonged to Goums, the Moroccan soldiers serving under French command who had relieved him on the Winter Line almost a year ago.

The lead tank trundled forward and stopped thirty feet from Sparks. A small French flag was flying from the tank’s radio antenna. He picked himself up and ran over to the tank. An officer jumped down from its turret. Sparks had never been so glad to see a Frenchman. Once again, he had escaped capture or worse. He pointed out where his men and the Germans were. The Frenchman climbed back into his tank and issued orders over his radio, and the tanks moved toward the Germans. Meanwhile, other Goums had jumped down from half-tracks and joined forces with Sparks’s men. “The ensuing battle lasted only a few minutes,” he recalled. “The surviving Germans, about thirty, were quickly disposed of by the Moroccans. Apparently, they had no use for prisoners.”

DAWN WAS ALWAYS the worst time. Heavy dew soaked into boots, the chill air sending shivers down sleepless men’s spines. They rubbed their hands together, pulled on beanies to keep their heads warm, checked their rifles, clipped in new magazines, and waited as the somber landscape changed from gray to green.

Chemical mortar rounds landed and large clouds of thick white smoke drifted across a field. Under the billowing screen, Sparks’s men moved toward a village called Housseras, northeast of Epinal. It had taken them more than a month to advance a little more than twenty miles, so stubborn was German resistance.

Men’s nerves were stretched taut as they stalked the enemy once more. The attack would either be a pushover or very tough going if the Germans chose to counterattack. They had been in continual combat since landing in France on August 15, and most, Sparks knew, were at their limit of endurance. They crept down wet lanes, skirted by bare trees, not knowing if they would see green leaves again. Combat never became less terrifying. It felt as if they were starting from scratch every time they closed on the enemy, cracking feeble jokes to keep their minds off what lay ahead, hearts pounding, stomachs contracting, calves twitching, muscles fluttering in their cheeks, jaws clenched, lips cracked with the dryness of fear.

That October 25, as the Thunderbirds entered woods near Housseras, the Germans opened fire with machine guns and mortars. Several men were killed and wounded. Later, in the quaint village of half-timber houses, a sniper perched in a church steeple stared through the calibrated glass of his high-velocity rifle’s sights and moved the crosshairs until they settled on an American. Then came the crack of a bullet, like a dry twig snapping underfoot, and yet another GI fell. By dusk, Sparks’s I Company had cleared the town but had lost its second, much-respected commander in less than six weeks, Lieutenant Earl Railsback, whom Sparks had held in high regard. If the killing continued at such a pace, he knew his Third Battalion would soon run out of experienced officers. The Thunderbirds had now been in combat for eighty-eight days straight, without receiving a single replacement.

IN THE LATRINES, rumors began to circulate that finally the Thunderbirds were to be relieved. When they weren’t cowering in foxholes under shellfire, trying to keep their feet dry, or defecating in icy slit trenches, men read letters from home and soggy newspaper clippings and laughed bitterly at predictions they would be home by Christmas. Clearly, the American public had not the remotest idea what was happening in Europe.

Early on November 5, Sparks ordered his Third Battalion to seize a village called St. Rémy, a few miles northeast of Housseras. By afternoon he had learned that K Company had come under heavy fire. He left his command post and set out to join his men. As he climbed a hill to reach K Company’s location, he recognized a man lying on a stretcher, his leg blown off at the knee. He had known twenty-one-year-old Sergeant Otis Vanderpool since he had been a platoon leader at Fort Sill in Oklahoma in 1941. Finally, the odds had caught up with him.

When Sparks moved closer to the fighting, he spotted Otis’s older brother Ervin, thirty-one, a platoon sergeant, but so intense was the firefight up ahead that he wasn’t able to tell him about Otis’s injury. Ervin had only joined the regiment so he could be keep an eye on Otis. Yet he had since proved to be a superb soldier. At Anzio, he had single-handedly saved his platoon when it came under attack, firing clip after clip from his M1 rifle at an armored car, finally scoring a direct hit and taking out the driver.

That evening, thirty-one-year-old Ervin was shot in the stomach and killed. It was uncanny that both brothers were hit, after so long in the field, on the same day. Perhaps Sparks should have offered Ervin a promotion or at least reassigned him to a noncombat position, as he had done with other men who had fought all the way from Sicily. According to Otis, who would eventually return to Colorado to face his parents alone, Ervin would not have accepted: “He wanted to stay near me.”

JUST TWO DAYS after the Vanderpool brothers were hit, the horror and heartbreak finally ended. Sparks and his men were pulled off the line for two weeks of badly needed rest. The forest fighting in the Vosges had pushed them to and beyond the breaking point. It was indeed a twitchy and demoralized battalion that was trucked to a rest area near the spa of Martigny-les-Bains, on a sheltered plateau, famous for its healing waters. Men’s jaws finally relaxed, leaving their faces slack, mouths hanging open, after months of tension.

“Who the hell do I see about a discharge?” asked one Thunderbird as he fumbled with trembling fingers to light a cigarette.

There were hot showers and movies. Every radio seemed to play Bing Crosby’s hit “White Christmas.” Sparks and his men tried to savor every second away from the front, getting dry, catching up on sleep, and writing long-delayed letters to loved ones. Sparks was careful, like every other Thunderbird, to avoid conveying the reality of the war to his parents and Mary back home, for fear of causing undue concern. Letters focused on the mundane, and on birthdays and weddings missed, and that November on Thanksgivings past and the approach of yet another away from home. In 1944 Thanksgiving fell on November 23. Eisenhower had ordered that every man in the European Theater be able to eat some turkey, whether served in a canteen or carried to a remote foxhole in a cold sandwich.

Many Thunderbirds also received forty-eight-hour passes to nearby cities. After being promoted, much to his surprise and delight, on November 14, from major to lieutenant colonel, Sparks is said to have visited a cabaret with a fellow officer. He tried to relax with a beer, only to overhear five enlisted men, who were clearly drunk, making loud and derogatory comments about officers.

“Shut your mouth!” ordered Sparks.

Sparks and his fellow officer apparently ended up in a fistfight with a couple of the enlisted men. Regardless of the provocation, it was a serious transgression for an officer who now had the silver oak leaves of a lieutenant colonel on his uniform. He was finally showing the strain of being so long in combat, even when resting. The close fighting in the forests of the Vosges, where men jumped at the sound of the wind, had pushed him to the edge. As with so many under his command, it was now only a matter of time before he also broke.