CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CASSINO ON THE MAIN

Icy-eyed GI’s darted through the flaming streets, killing the vicious German troops like mad dogs.

PAUL HOLLISTER, “THUNDERBIRDS OF THE ETO,” IN OLECK, ED., EYE WITNESS WORLD WAR II BATTLES

Thunderbirds fight through the ruins of Aschaffenburg, Germany, March 1945. [National Archives]

THE THIRD BATTALION BOARDED trucks and was driven toward Aschaffenburg, with Sparks following in his jeep. After two hours, the convoy neared the Nilkheim railway bridge across the Main. At a ridgeline, Sparks stopped the trucks. He wanted to take a good look at Aschaffenburg, lying below him on the eastern banks of the river.

The city rested on a bluff some forty miles upriver from Frankfurt. Forested foothills of the Spessart Mountains rose to the north, east, and south. Through his field glasses, Sparks could make out two main landmarks: the Schloss Joahnnesburg, a seventeenth-century castle, and the tenth-century Stiftskirche, a Roman Catholic basilica that sat atop the city’s highest point, the Dahlberg. To his surprise, he could not see any American troops in the city. There was no movement at all.

Something’s wrong. If the Third Army took that place, there should be some Third Army troops.

He looked down again at the railroad bridge. All was quiet. There was no sign of the enemy. The bridge had been covered with planks to allow troops across. But he felt uneasy all the same. He ordered his men off the trucks and then reconnoitered ahead on foot with his runner Johnson and a few other men until he got to within a mile of the bridge. Again the area was deserted. Around 2 P.M., Sparks ordered a platoon of around forty men to cross the bridge. The silence continued until a full company of two hundred had crossed the bridge and begun to move into streets on the eastern side. Then Sparks heard the unmistakable sounds of German small-arms fire and mortars in the distance. His men scattered, looking for shelter.

Sparks was furious. He had been told that Patton’s Third Army had secured the city. Clearly, that was not the case. Fearing a German counterattack, he ordered his three companies to set up defensive positions across the bridge, on the eastern bank of the Main, in the outskirts of the city that had supposedly been made safe. As his men set up machine-gun positions and mortars, Sparks made contact with a reconnaissance troop of around a hundred men from the 4th Armored Division, which belonged to Patton’s Third Army. They were dug in near the bank of the river, upstream from the bridge, and led by a young captain.

“Colonel,” said the captain, “I’m glad to see you.”

“What’s going on here?”

“Well, Colonel, there’s a hell of a lot of Germans still here. German civilians tell us there’s at least five thousand.”

Five thousand?

That was five times the strength of Sparks’s battalion. Most of his privates were replacements, and all of his men were less than eager to engage the enemy in fierce close combat, especially so near to the end of the war. In recent weeks they had encountered far more civilians waving white flags than they had enemy soldiers with guns. Indeed, they had assumed the war was all but over.

The captain gathered his men and prepared to leave. He clearly had no stomach for the fierce fighting he knew lay ahead.

“I was ordered to stay here until relieved and guard the bridge,” he explained to Sparks.

“I guess you’re relieved,” said a caustic Sparks.

Sparks then radioed back to the division.

“There’s no way I can take this area with one battalion.”

Sparks was told that the rest of the regiment would arrive the next morning. He was to hold his position through the night.

As dusk settled, there was considerable bitterness among Sparks’s men. They felt they had been cruelly deceived. Yet again, they had been given the rough end of the deal. It was supposed to have been a SNAFU (Situation Normal, All Fucked Up) as GI slang had it, not a FUBAR (Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition). Elements of the 4th Armored, Task Force Baum, had in fact passed through the area but had not stopped to secure it. Instead they had been bound for Hammelburg prison camp, some seventy miles away, on a highly secretive mission to free George Patton’s son-in-law, Colonel John Waters, who had been captured in Tunisia in February 1943. The foolhardy rescue attempt, ordered by a reckless Patton, would fail catastrophically within a matter of hours, with all but fifteen of the three-hundred-man force captured, killed, or wounded. From start to finish, the whole exercise was a tragic fiasco. The suicidal “Hammelburg Raid,” as it was called, was far less forgivable than slapping shell-shocked GIs. It would certainly have cost Patton his career had it not been quickly covered up and its survivors sworn to silence.

The city had not been taken—far from it. Task Force Baum had passed by in the night but had not gone unnoticed. Festung Aschaffenburg (Fortress Aschaffenburg), like a hornet’s nest, had merely been tapped unnecessarily with a flimsy stick. Now Lamberth’s most fanatical troops were stirring.

There was, however, some good news that evening. Captain Anse Speairs, the regimental adjutant, had made an extraordinary discovery a few miles from the Nilkheim Bridge: a huge warehouse of more than a million bottles of fine wine and liquor that had been seized from all over occupied France. He returned to the regiment’s mobile headquarters—where the staff was preparing to reinforce Third Battalion the following morning—with a jeep loaded with twenty-three cases of the finest French brandy he had ever seen. Soon, every available truck in the regiment was dispatched to the warehouse to liberate more cases of brandy, at least 640 cases of vintage wine, as well as countless other bottles of assorted liquor and champagne.

“You’ve got a problem,” Speairs told regimental commander Colonel O’Brien. “Do you want the wine or the cognac?”

There was only so much room in O’Brien’s trailer. He couldn’t take it all.

What O’Brien couldn’t take was quickly shared throughout the regiment that night. One battalion issued twenty-six cases of brandy to each company—more than one bottle to each Thunderbird. Ever inventive, a thirsty GI quickly devised a potent new cocktail, the soon-to-be-famous “157th Zombie,” consisting of cognac, Bénédictine, and Cointreau; most men agreed it was best followed by a champagne chaser. It would be several days before some canteens actually carried water rather than wine.

If it was Dutch courage the Thunderbirds needed, they now had plenty of it. In a supply run, cases of booze were apparently delivered to the Third Battalion that night as it guarded the Nilkheim Bridge. The uneasy silence was split not by machine-gun fire but by the sound of popping champagne corks. Some Thunderbirds got blind drunk, but others opted to stay sober, anxiously awaiting the dawn. They didn’t want to have to fight the Germans with a hangover.

Cranston Rogers in G Company was ordered to take his platoon and cover the railroad bridge’s southern approach that night. In his entire six months in combat, he had never been so scared. According to his company commander, a division of German troops, more than ten thousand men, was gathering a few miles away before heading to retake the bridge. Sparks and his battalion would be outnumbered ten to one.

IT WAS A relief to see the trucks cross the Nilkheim Bridge at first light, and Thunderbirds from the regiment’s First and Second Battalions form into squads and platoons. As promised, the rest of the regiment had arrived. After a sleepless night, Cranston Rogers, the platoon guide in G Company, was equally relieved that the story about the German division coming to attack in the night had turned out to be a false alarm.

In almost five hundred days of combat, the Thunderbirds had not been ordered to clear a heavily defended urban area. Doing so was always costly, for it meant engaging the enemy at close quarters by clearing houses room by room. Resentful Thunderbirds from all three of the regiment’s battalions now prepared for the worst. Officers checked their pistols. Rifle squads armed themselves with extra grenades, sharpened knives, grabbed crowbars and axes for breaking through doors, and organized themselves into “search groups” of up to six men. One or two men in each group would enter a building first, covered by the others, and then try to kill any defenders without being hit first.

Having come so far, it was agonizing for Sparks to have to commit his men to a form of attrition that made no strategic sense whatsoever—the German high command had nothing to gain from Aschaffenburg’s defense. That morning, under a murky sky, his battalion made very slow progress. By lunchtime, the advance had become infuriatingly costly and tough going. It seemed as if snipers’ crosshairs covered every open window and rubble-strewn crossroads. To his shock, Sparks learned that in the suburb of Schweinheim, Company L had attacked across open fields and lost all of its officers in just five minutes. Not since Anzio had so many men fallen so fast, more than fifty wounded from the regiment in only a few hours. By late afternoon, his entire battalion had stalled. He ordered his men to dig in while the 158th Artillery tried to soften up defenses.

That evening, unsettling rumors began to spread that some civilians were fighting alongside the uniformed German defenders. According to one report, young girls were hurling grenades from roofs, and wounded soldiers from a military hospital had even joined the fray, egged on by both Major von Lamberth and a local Nazi Party ideologue, Kreisleiter Wohlgemuth, who had recently issued a proclamation: “Whoever remains in the city belongs to a battle group which will not know any selfishness, but will know only the unlimited hatred for this cursed enemy of ours.”

“Nun Volk steh auf und Sturm brich los!” declared Aschaffenburg’s most fanatical defenders. “Now the people stand up and the storm breaks loose!”

THEY ATTACKED AGAIN at dawn—all three battalions in the regiment. “It was tough, tough, tough, tough,” recalled Sparks. It appeared that Germans were hidden behind every window and door. He could not use artillery in some areas because his men were often just yards from the enemy. In some rooms, they were only inches away from Hitler’s last stalwarts, forced to kill or be killed with daggers and pistols. At one point, his men came under fire from one of their own tanks that had been captured and hastily repainted and identified with the German white cross. Sparks ordered his accompanying tank destroyers to eliminate the seized Sherman. They did so, but not long after, the leader of the tank destroyer platoon and Sparks’s operations officer were both hit and had to be taken back to an aid station, joining fifty-nine other men from the regiment wounded that day.

Later that afternoon, Sparks went in search of somewhere to set up a command post. Karl Mann sat in the back of a jeep with Sparks’s runner Johnson, behind Turk and Sparks, as they reconnoitered a deserted street. At a crossroads, Turk stopped close to a Sherman tank and Sparks spoke with its crew. Soon after, recalled Mann, Sparks found a cute little dog in a deserted house nearby and decided to keep it. They then returned to the crossroads. In their absence, the Germans had shelled it and several of the tank crew had been wounded. Mann wondered what might have happened had they stayed just a few minutes longer at that crossroads.

As night fell, the costs of securing Festung Aschaffenburg became depressingly clear: The regiment’s aid station recorded its highest daily casualty count so far. From the top to the bottom of the division, frustration and a hardening anger set in. The only good news that night for some officers was that Captain Anse Speairs, whose job it was to scout out potential command posts, had yet again found a safe and comfortable headquarters for the regiment—a hotel that had been abandoned in a rush by the pregnant wives and girlfriends of SS troops. “There was a good supply of baby bottles and nipples,” recalled Speairs, “some Swiss chocolate and the bar still had beer on tap.”

Meanwhile, the Germans tried to cut off the American forces by destroying the Nilkheim Bridge across the river Main. Two of the world’s first combat fighter jets—formidable Me-262s*—attacked the bridge but failed to destroy it. German Navy frogmen also attempted to blow it up by placing a torpedo against its sandstone center support, but they were spotted by sentries as they floated down the river toward the bridge. Mortars opened up and one round landed among the four intrepid frogmen, detonating the mine they were carrying and killing them all.

BY DAYLIGHT, THE entire division had been committed to the battle—three regiments numbering over five thousand riflemen. Yet casualties continued to mount. Sparks ordered his men to employ direct fire from heavy-caliber weapons as they tried to clear out German positions. Every mobile piece available was quickly deployed. The M36 tank destroyer had a highly effective 90mm gun and proved particularly effective, as did the M4A3 tank with its 76mm gun. Sparks watched as these vehicles blasted away, often at point-blank range. Then Thunderbirds stormed the positions. The Germans answered round for round, landing hundreds of mortars on Sparks’s battalion. In one fifteen-minute spell, more than two hundred rounds fell on his men, one every five seconds, sounding like a vicious hailstorm.

As far as Captain Anse Speairs at regimental headquarters was concerned, it was time to offer an ultimatum to the Germans in the hope of saving lives. He suggested to regimental commander Colonel O’Brien that he drop on the town from a plane some leaflets demanding surrender or else the city would be completely flattened. Speairs finally managed to get approval at division level.

That afternoon, he found himself sitting in a Piper Cub spotter plane above the city.

Speairs opened a window and dropped two hundred leaflets on the Germans. “Your situation is hopeless,” read the handfuls of mimeographed leaflets, addressed politely to The Commandant of the City of Aschaffenburg. “Our superiority in men and material is overpowering. You are offered herewith the opportunity, by accepting unconditional surrender, to save the lives of countless civilians.… Should you refuse to accept these conditions, we shall be forced to level Aschaffenburg.”

Sparks’s men reached the strongest points of resistance by late that afternoon, penetrating as far as the artillery barracks, the Artillerie Kaserne, in central Aschaffenburg. By nightfall, they had split the city in two but were struggling to hold their gains because of German infiltration. Snipers would crawl through rubble and sewers into buildings that had been cleared by Sparks’s men and then open fire on them from behind.

Mopping up such resistance usually meant sudden death for either an American or a German. Thunderbirds kicked in doors, lobbed in grenades, ran inside to see who was still alive, who wanted to surrender, and who wanted to die. Then they yelled upstairs for others to come down and give up. If nobody answered, they had to creep upstairs to check, hoping there weren’t more Germans waiting with grenades in a bedroom or the toilet.

When running from one house to another, or across a street, it was safest to do so in squads, each man a few yards from the next. Snipers didn’t usually fire at groups, preferring the lone soldier. Squads had a tendency, if they lost a man, to hunt down the sniper with a vengeance. As was the case throughout Germany that spring, not many snipers, recognizable by the bruises on their faces from a rifle’s recoil, were taken alive.

Just like killing, surviving this kind of warfare required one to act counterintuitively. When bullets started buzzing past, Sparks’s men instinctively wanted to drop their heads and kiss the rubble. But if they all did so and then clustered, they provided an ideal target, especially to an MG42 machine gunner. The experienced men knew they should always hold their heads up with their eyes open and stay on the attack. It was the best way to stay alive.

In some streets, recalled First Sergeant Cranston “Chan” Rogers, the G Company platoon guide, he had to fight against a curtain of small-arms fire. It was the utter randomness of the killing—the feeling it induced that any man could die unfairly at any second—that would still haunt him many years later. Ordered by his company commander to take a schoolhouse, Rogers joined a young lieutenant and others from his platoon in a frontal assault on the schoolhouse held by a hundred Germans.

“Let’s go,” ordered the lieutenant.

Rogers scrambled up a pile of rubble. He stumbled and fell flat on his face. His helmet came off as he dropped his rifle. He was stunned for a moment. The lieutenant and his runner kept going. They were both cut down by a machine gun and killed. Had he not stumbled, Rogers too would have been dead.

The fighting only intensified as the Thunderbirds tried to eliminate German strongholds in the center of the city. In the Bois-Brule Barracks on Würzburger Strasse, Sparks’s men wounded or killed every German defender. Unprecedented quantities of white phosphorous were fired into cellars to smoke the enemy out. Explosions ripped at the eardrums every few seconds, the constant barrage sounding to stunned defenders as if a gigantic machine gun had opened up on them. Any building or high point in the city from which German fire could be directed was quickly destroyed, including the Roman Catholic basilica’s steeple, the highest point in the city, which was demolished by twenty-five artillery rounds. Nothing was sacred. Only God knew when it would end.

THE LOW-LYING CLOUD above Aschaffenburg cleared on the fourth day of the battle, April 1, 1945, and an increasingly frustrated General Frederick was able to call in air support. A P-47 fighter-bomber squadron attacked using .50-caliber ammunition because of fears that bombing might kill Americans below in the burning and shattered city. But the strafing runs were ineffective, and so the P-47s were instructed to bomb specific targets such as the Gestapo headquarters. Fighter-bombers were soon flouting curtains of 20mm anti-aircraft flak and striking all across the city where resistance was strongest.

Around a thousand Germans kept on fighting. Lamberth’s overall strategy—Auftragstaktik—to hold off the Americans for as long as possible was proving agonizingly effective. Then, for the first time in Europe in World War II, it was reportedly decided to use napalm on a civilian area. The napalm, essentially jellied petroleum, added a particularly deadly fuel to flames that engulfed more and more of the city.

The air strikes seemed to make no difference, nor did the napalm, the phosphorous that burned to the bone, the tons of high explosives, the thousands of artillery rounds aimed at strongpoints each day. Still the Nazis held out. So stubborn in fact was the resistance that Allied Supreme Command even considered issuing a directive, eerily like Lamberth’s, that any German civilian would be shot without trial on the spot if found bearing arms.

Four times that Easter Sunday, Lamberth’s fanatics were dislodged from their hiding places in ruins yet managed to creep back through sewers and the skeletons of buildings into Thunderbird positions in the town’s center and inflict casualties. Aschaffenburg was indeed what one newspaper described as a “half-destroyed city of death.”

“Hate is our prayer,” announced Deutschlander radio in a national broadcast that day. “Revenge is our battle cry.”

LAMBERTH AND HIS men clearly still possessed the energy and obedience that had made the Wehrmacht so hard to destroy, from Sicily to Anzio, from the Vosges to the river Main. But they were not, after all, Supermen. Finally, that evening, facing another long night of close combat and relentless shelling, cornered in hopeless positions, low on ammunition and out of water, some of the defenders began to surrender.

Sparks was surprised how old some of Lamberth’s warriors were: over fifty in some cases. The German Army was clearly running low on manpower, however fanatical its resistance. Others who wandered toward the Thunderbirds’ lines in tearful dazes, arms above their dirty faces, wore uniforms several sizes too big. They were mere boys, yet to grow stubble or taste alcohol. That March of 1945, sixty thousand German sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds were sent into battle, often with just a few days’ training.

Late on Easter Sunday, Sparks reached Aschaffenburg’s central square. A gruesome scene awaited him. Two German soldiers, executed on Lamberth’s orders, had been hanged from a gallows with signs pinned on each of them: THIS IS THE REWARD FOR COWARDS.

WORN DOWN BY the constant shelling, hundreds more Germans began to throw down their weapons and wave white flags. The most eager to escape the American onslaught were traumatized women and children, some three thousand of whom still remained in the shattered city, cowering in cellars and bomb shelters.

As the Thunderbirds closed on the last SS holdouts in the city, many civilians tried to break out of Festung Aschaffenburg, much to the displeasure of the more fanatical defenders. One young Thunderbird, Harry Eisner, caught sight of a crowd of around a hundred moving toward him. Some were walking and others running. Then he heard rifle shots and saw civilians fall dead, fired upon by their own countrymen. Others kept on, walking and running, undeterred.

Eisner spotted a pretty schoolgirl. Her pale arms were folded tightly across her stomach. Her socks drooped around her ankles. She had an ashen face.

She was a laughing child once.

The girl looked so terribly sad. Eisner would never forget that she wore a faded blue dress and had a pigtail. Soon, she stood right in front of him and he saw a thin red line across her stomach. He realized that she was bleeding. He tried to move her arms from her stomach. She resisted, keeping them firmly in place. He opened the collar of her dress and saw that she had been badly wounded. Her arms were all that were keeping her from being disemboweled.

Eisner picked her up and held her tenderly. He was determined to save her. He no longer felt tired. Adrenaline coursed through him as he turned to other Thunderbirds for help. They too were galvanized by the girl’s plight and were soon clearing the nearby road so that a medic in a jeep could get to her. Killing Krauts did not matter now. All that counted was saving this one child, preserving a life rather than taking one. Finally, the medic arrived. Eisner felt his heart pounding as the medic tended to the child, injecting her with fluid. She still had her eyes open. Their steady gaze never left Eisner as the medic carried her to the jeep and then placed her gently in it. She kept looking at Eisner, even as the jeep pulled away.

THE THUNDERBIRD WAS with a German captain when he arrived at Colonel O’Brien’s command post. He had been captured in fierce combat and had been allowed to return to his own lines with the German, who bore a note from Aschaffenburg’s military commander. It was excellent news: Lamberth was finally prepared to surrender if the Americans would send someone to his headquarters to negotiate terms.

Colonel O’Brien was, however, in no mood to negotiate and refused Lamberth’s offer. Instead, he told the German officer to tell Lamberth to surrender at once or air strikes would intensify and the entire city center, as well as its outskirts, would be pulverized. There would be unconditional surrender or total destruction, consistent with the broader Allied approach in subjugating Nazi Germany.

A brave German-speaking American lieutenant accompanied Lamberth’s officer back to the German headquarters. Thankfully, Lamberth agreed to O’Brien’s demand, but he would not himself surrender to a mere lieutenant. Sparks was the most senior officer available in the vicinity of the Old City where von Lamberth was holed up, and so he was instructed to take Lamberth’s surrender in person.

Sparks, his interpreter Karl Mann, and his runner Johnson arrived at Lamberth’s headquarters later that morning. Lamberth emerged, holding his pistol belt and holster in one hand. With the other, he saluted Sparks before handing over his gun. Then he ordered all of his fellow officers to give up. Soon, they had all dropped their pistols at Sparks’s feet. To the end of his life, Sparks would prize Lamberth’s Luger.

Sparks knew Germans were still holding out in several places. So he turned to Karl Mann, his interpreter.

“Tell the major he’s got to go with me,” said Sparks. “We’re going to all these remaining strong points.”

Lamberth rode on the hood of the jeep, holding a bullhorn, and ordered his men to give up. His defense of the city had been totally pointless. Sparks had only contempt for him. His devotion to Hitler had cost thousands of lives and reduced a beautiful, ancient city to a vast field of rubble. He had executed honorable men for suggesting surrender, and yet here he was, walking from one shattered building to another, holding a white flag, ordering boys and old men to lay down their weapons.

At last, silence descended on Festung Aschaffenburg. When the last Germans had given up, Sparks turned Lamberth over to officers who took him back across the river Main, where he formally surrendered to Colonel O’Brien. I Company medic Robert Franklin watched as other Germans were escorted from strongpoints to be processed into POW camps, the so-called cages, which now swelled throughout Germany with hundreds of thousands of vanquished Nazis. Even in defeat, some were full of spit and vinegar, astonishingly arrogant. Franklin saw a German officer marching alongside his captured men, shouting abuse at an American officer. The American walked over to the German and kicked him hard in the backside. The German looked humiliated and fell silent.

Then the looting began. Some Thunderbirds smashed windows of a jewelry store and pocketed everything in display cabinets. Franklin also saw men from his own I Company, now commanded by a Lieutenant Bill Walsh, enter a German headquarters and break into a safe containing a large amount of German payroll. One of the thieves handed Franklin a handful of several hundred thousand marks. Franklin gave most of the banknotes to other men in his unit as souvenirs, not realizing that the money could actually be used. “Had I known it was good,” he recalled, “I would have bought some hotels and cafes and other property in Aschaffenburg.”

In the defense of Aschaffenburg, the Germans had suffered more than 5,000 casualties. At least 1,000 were killed. It was a heavy price to pay for useless ground, but a mere fraction of the 284,000 fatalities suffered by the German armed forces that March of 1945. The regiment had lost 200 men, 90 from Sparks’s battalion alone. Eleven officers had been killed.

Lamberth’s fanatical resistance had shocked not only the Thunderbirds but also the American high command. No less than secretary of war Henry L. Stimson had learned of the intensity of the siege and soon told reporters: “Nazi fanatics used the visible threat of two hangings to compel German soldiers and civilians to fight for a week.” Such behavior meant he must now make it clear to the German people that their “only choice is immediate surrender or the destruction of the Reich city by city.”

IT WAS BEHIND him now, the “Cassino on the Main,” its smoldering ruins and fires receding into the distance. Sparks pressed on, heading south toward Bavaria, the birthplace of Nazism. Shaken by the fanatical resistance in Aschaffenburg, some of his men riding in trucks believed rumors of a Nazi suicide mission to stall the advance once more. Thankfully, the counterattack failed to materialize and the Thunderbird caravan rolled on, smashing through “sixty-one minute” barricades hastily placed in streets by the increasingly pathetic Volksturm and other halfhearted resisters. “Sixty minutes to build them,” Thunderbirds joked, “and one minute to knock ’em down!”

In the savage close combat at Aschaffenburg, many of the men had passed a point of no return. “I didn’t feel sorry for any Germans after Aschaffenburg,” recalled Sergeant Rex Raney, who had fought all the way from Sicily. “When women and kids hold you off, war takes on a different atmosphere.” Raney had accidentally stepped on part of a blown-up German soldier in the city and tried everything to clean his boots but wasn’t able to get rid of the stench of death, even though his sense of smell had been severely impaired at Anzio. “My boots stunk so bad—death walked with me for about five days before I got a new pair. I left the old ones for some Frenchman.”

The Thunderbird convoy built up speed as it made toward the Danube River. Spirits rose. The confidence of conquerors returned. Men pulled out bottles and began to drink. There had been little time to savor the wonders of France during the long march to Germany. At last some of the old-timers discovered what the ripening grapes they had seen were capable of producing—the best wines in the world.

There had been so much booze stashed in the liquor warehouse that the Thunderbirds had not been able to bring it all with them. So Sparks and others had decided to bury some of the bottles, vowing to return for the hidden caches. On they rolled, through villages where from every window there seemed to hang crisp white sheets. Men opened more bottles and toasted the imminent fall of the Third Reich. A few undoubtedly sipped the vintages with hearts full of hate, determined to wreak vengeance. They had lost their best friends for no good reason, so close to the end.

* The Me-262 could fly at 528 mph—ninety more than any Allied plane in the ETO.

Lieutenant Van T. Barfoot (right) near Epinal, France, after receiving the Medal of Honor, September 28, 1944. [National Archives]

Lieutenant Earl Railsback, one of Sparks’s finest young officers, killed in the Vosges, fall 1944. [National Archives]

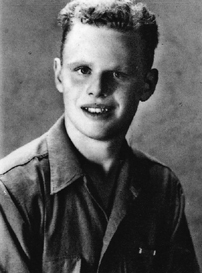

Karl Mann, Sparks’s German-born interpreter. [Courtesy of Karl Mann]

Johann Voss, SS Black Edelweiss machine gun squad leader. [Courtesy of Johann Voss]

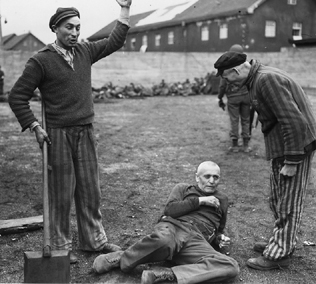

Medics take a German prisoner (left) and an American to an aid station near Aschaffenburg, March 31, 1945. [National Archives]

Tanks attached to 157th Infantry Regiment clear buildings of snipers in Aschaffenburg. [National Archives]

Barricades created by Germans in Aschaffenburg, March 1945. [National Archives]

German civilians flee their homes, which have been set on fire by Thunderbird tanks trying to eliminate snipers in Aschaffenburg, March 28, 1945. [National Archives]

American tanks roll through ruins of Nuremberg, April 20, 1945. [National Archives]

German troops captured in Nuremberg, April 20, 1945. [National Archives]

American tanks take to one of Hitler’s famous autobahns, April 1945. [National Archives]

Thunderbirds from 157th Infantry Regiment cross the Danube on April 26, 1945. [National Archives]

The infamous “death train” containing about 2,000 dead people, which Sparks and his men discovered near the entrance to Dachau on April 29, 1945. [National Archives]

Sparks’s men in I Company run toward the shelter of woods near the entrance to Dachau, April 29, 1945. [National Archives]

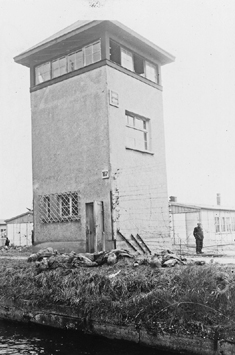

Entrance to the Dachau complex, shortly after liberation. [National Archives]

Dachau inmates assault an SS guard in the coal yard on April 29, 1945. [National Archives]

GIs inspect boxcars at Dachau shortly after liberation. [National Archives]

Sparks’s men rounding up German soldiers in Dachau. [National Archives]

SS guards killed by American liberators lie beside a guard tower at Dachau concentration camp. [National Archives]

Robert Frederick, 45th Division commander (center), arrives at Dachau, the afternoon of April 29, 1945. [National Archives]

Robert Frederick being shown the crematorium at Dachau by an inmate. [National Archives]

Three of 32,000 inmates liberated from Dachau, photographed on April 30, 1945. [National Archives]

Sparks’s 157th Infantry regiment comes to attention in Munich for decoration ceremonies, May 24, 1945. [National Archives]

Felix Sparks, commanding general, Colorado National Guard, 1960s. [Courtesy of the Sparks family]