Chapter IV

I Ready Myself for China

The days passed quickly. My journey was to commence in under a week. After a quiet dinner at the nearby Great Western Royal Hotel I clambered up to the box-room where my tackle and clothing from Army days were stored in moth-proof trunks. ‘The East India Vade-Mecum’, my first guidebook for military service in India, lay among the memorabilia. It counselled voyagers to take ‘a washbasin, a chamber pot, a pound of tea, five pounds of sugar, soap that could be dissolved in salt water and both a horsehair and a feather pillow’ - the latter for cold weather, the former for warmer climes. As on that first adventure, I would take an assortment of emergency drugs, a few diagnostic instruments and a small leather-cased amputation kit.

I considered my wardrobe. For the rough terrain en route to northern China a trip to tailors Gieves and Hawkes would be in order. On each of my visits a now-elderly cutter reminded me that Gieves tailored the uniform Admiral Lord Nelson wore when he died aboard HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar. And that when Henry Mortimer Stanley came across David Livingstone in the town of Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika on 27 October 1871, the former was clad head to toe in Hawkes & Co. dress. Even Livingstone wore a Gieves Consular hat.

My formal wear too was in severe need of an update. I would order a bespoke frock coat, grey, with silk-faced lapels, and perhaps a matching grey silk cravat. My existing waterproof horse-hide shooting boots had seen better days and needed replacing.

Food would be a problem on the long route. Mycroft Holmes could send stores to way-stations ahead - a few dozen 2lb lever-top canisters of the ‘McDoddie’, preserved carrots, celery, French beans, Julienne, leeks etc. (‘cannot be distinguished from the fresh’) described favourably in The Lancet as maintaining the true flavours and, as important, the peculiar chemical conditions of the food constituents. An electric torch would be convenient but obtaining fresh charges an impossibility. Instead a couple of Italian Alpine Club lanterns and a ball of spare wick, a gallon of oil of the best quality and wax tapers would serve nearly as well. Plus a 3-draw spyglass in a leather case. For compiling notes I would take my favourite stylographic pen and a stone bottle of Draper’s dichroic ink. By contrast with writing-ink, the latter is quite unaffected by wet.

I dropped in at Salmon & Gluckstein of Oxford Street (‘Largest and Cheapest Tobacconists in the World’) to purchase a half-dozen tins of J&H Wilson No. 1 Top Mill snuff, a few Churchwarden clay pipes, and a box of Trichinopoly cigars manufactured from tobacco grown near the town of Dindigul.

***

That evening I went to my work-table and took out a top-breaker six shot revolver in .476 calibre with a bird’s head grip and two spare barrels. New rounds can be reloaded quickly. Given Mycroft’s and the Chinese General’s dire warnings I would include the bespoke shotgun inherited from my father, after taking it in the morning to Athol Purdey for servicing. A stroll back to the Army & Navy Stores for a supply of Spartan sauce and a few tins of preserved soup, followed by a meal at The Holborn would complete a pleasant day.

An imperious knocking called me to the side-door. A messenger-boy handed me a telegram and pushed a palm at me for a gratuity.

‘Mister,’ he said, pointing at the sturdy revolver in my hand, ‘my grandfather has one just like that. Webley-Pryse, ain’t it? He spends his evenings cleaning it with a rag too.’

I opened the telegram. It was from Holmes.

‘Dear Watson,’ it read. ‘Inconvenient for you to visit right now. Shall explain at some other time.

Yrs S.H.’

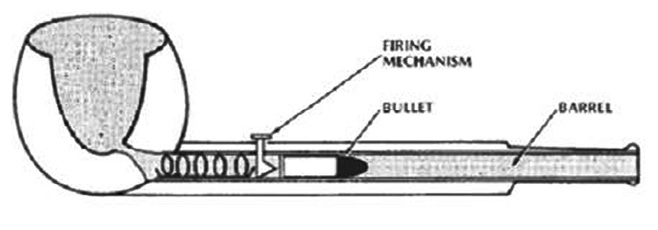

P.S. Am busy designing a single-shot pistol. Prototype as below. In your judgement what calibre would be best? .25 or perhaps .22 (if .22, short or long?).

I tossed the telegram into a waste-paper basket. At least I would avoid inadvertently giving the game away. I would reply later, recommending the .25 calibre.

Another rat-tat at the same side-entrance a half-hour later presaged the delivery of a weighty parcel from Foyles, ‘the world’s first purpose-built bookshop’. It contained Major C.F. Close’s text-book of topographical and geographical surveying. In case I needed to pass myself off as an archaeologist, I ordered the account of excavations at Anau in the foothills of the Kopet Dagh. Ostentatiously tucked under an arm it could be useful for averting suspicious eyes as I passed through borders between one wild region to the next.

***

The day of departure arrived. A two-horse Hansom carriage dropped me at the boat-train platform for Southampton. The same high excitement coursed through me as thirty years earlier when I set off from exactly the same platform to catch a troop-ship for Bombay to begin my life as an Army doctor. This time a second Hansom accompanied me with the overflow of baggage. The elderly porter ran an inquiring eye over the assemblage of trunks, bags, leather valises, battered tin-box and packages crowding the platform at my feet. He took off his cap, scratched his head, peered at me and asked waggishly, ‘Away for the entire weekend, are we, Sir?’

I handed him a half-crown - a handsome gratuity –and advised him to keep it to place on a horse called The White Knight at the next Ascot Gold Cup.

Exhaust steam vented upwards into the atmosphere through the monster chimney, giving rise to the familiar chuffing sound at the start of many an adventure. The seat opposite me was vacant, empty of a Sherlock Holmes clad in his Poshteen Long Coat with its many flaps and pockets. I wondered what Holmes would make of it when eventually I was able to let him into the secret, that for once I was the principal player in the mission - and at the request of His Majesty’s Government. For the first time since my India and Afghanistan days I would not be the side-kick or, as a rude American described me - in print - ‘the great Detective’s Performing Flea’.

The platform guard waved his green flag with a flourish worthy of a colour guard. I was about to slam the carriage door when the chauffeur who had delivered the invitation from Grey and Haldane came running down the platform and thrust a package into my arms. He fell back as the train pulled away, hand still held to forehead in a salute.

The parcel, the size of about half a dozen books, contained a curious box-like apparatus. An accompanying note from Mycroft Holmes wished me well and offered an explanation. A sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence would soon be formed to investigate the potential of flying machines for reconnaissance and artillery observation. A Pole by the name of Prószyński had approached them with the ‘Aeroscope’, a new hand-held film camera he planned to patent and manufacture in Britain. An ingenious compressed-air system made it possible to film in the most difficult circumstances, from airplanes and for other military purposes.

Before considering ordering some hundreds of Aeroscopes the War Office wanted it tried out in precisely the harsh conditions I would meet on my journey to Peking. The device came with several 400-foot reels of 35mm film and a small bicycle pump to compress the air. It was, Mycroft advised me in parenthesis, the only Aeroscope at present in existence. I placed the device in my tin-box alongside my favourite camera, the Lizars 1/4 Plate Challenge Model E.

I settled back uneasily. An hour with Sir Ernest Satow, the recent British Envoy in Peking, at his quintessential English gentleman’s club, The Travellers, had left me with deep misgivings.

‘Take the Yellow River as a metaphor,’ were Satow’s cautionary words as he saw me to the street. ‘Unfathomable to every Western investigator the Chinese unquestionably are. Treacherous they may well be. One may as well seek to peer into the muddy waters eddying around the piles of the ... (he mentioned some bridge over the Yangtze River) as hope to penetrate the mystery behind the eyes of the Chinese people.’

He took my hand in a farewell shake.

‘Remember, Watson, the man who presumes to interpret the Chinese mind is doomed, his theories snares, his conclusions perilous.’

Those final words of Satow’s would stay with me for a very long time.

***

Mid-September. The start of my travel diary though so far nothing to report. The waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth, the English Channel, came and went. So too Brussels and Berlin. And Moscow. Am crossing immense stretches of the Russian plain that saw some of the last horse-mounted nomadic tribes of Europe, the Tatar of the Golden Horde. Now the hardest part lies not too far ahead.

October 4. Today is the fourteenth day sailing down the River Irtish in a shallow-draft steamer to the Russian outpost of Zaissan. The steamer leaks badly. Every morning the Captain pays obeisance to the God of the Rivers, before we start. The crew and half the passengers join in with him. The other half of the crew and passengers spend their time in the bilges removing the water and plugging new leaks. The journey is giving me time to start recording my thoughts for the lesser of my assignments, China’s first New Army Field Service Pocket Book. I plan to include concise information on every conceivable contingency faced by the serving officer - from subaltern on the furthermost Frontier to staff officer at Headquarters. I shall start with advice for moving badly-sited garrisons to more favourable ground, reminding the engineers that no natural or artificial strength of position will of itself compensate for loss of initiative when an enemy has time and liberty to manœuvre. The choice of a position and its preparation must be made with a view to economizing the power expended on defence in order to increase the power available for offence. That should be clear enough.

With the world of aviation growing apace I plan an appendix on Aeronautical terms and their meaning, e.g. ‘Aeroplane’ - a flying machine heavier than air. ‘Fuselage’ - the outrigger connecting the main planes with the tail-piece or elevator. ‘Nacelle’, the enclosed shelter for the pilot of a biplane. Etc.

At Sir Edward Grey’s personal request I have also started to keep notes on natural phenomena. When he and I parted at the Foreign Office he presented me with a manuscript copy of a work he plans to publish privately. It will be dedicated in memory of his deceased wife Dorothy under the title A Cottage Book. My first note records a remarkable fact: I find myself in a region where there is hardly any autumn colouring. The leaves die green.

October 6. Along with nearly all the passengers I have left the waterlogged steamer. Today on trek to a fort near the remote village of Mo-tao-chi I came across another curiosity of Nature, a gigantic conifer. The tree with its beautiful light-green ferny spring foliage may be completely unknown to European dendrologists. The village headman led me to the stand just as dawn broke. It reminded me of the California Redwood. I shall informally name it Dawn Redwood. I have collected a pocketful of seed to hand to the Royal Botanical Gardens on my return. If it turns out to be unknown to science perhaps the Society will name it Sequoia watsoniana.

Avery different curiosity of Nature leapt into my tent unbidden today, a big green grasshopper with a reddish head and a broad amber stripe all down its back. We had a good look at each other. It stayed a while before giving a prodigious spring back into its own world.

October 10. Have wended my way to the settlement of Semipalatinsk on the Irtysh River, the ‘Seven-Chambered City’, so named from a long-gone monastery with seven buildings. We have left Russia’s silver birch forests and the Ural mountains well behind, along with Russia’s influence. For the foreseeable future, large stretches of my journey must be undertaken on foot, eastward into the eye of the rising sun, only the baggage carried by horse and mule. The pretty 10-rouble gold coins with Tsar Nicholas II on one side and the double headed eagle of the old Byzantine Empire on the other are now a rarity. My pocketful of Mexican dollars is coming in useful.

I switched to a horse-drawn tarantass to reach the frontier at Bakhty and on through Urumchio to Chinese Turkestan. In such fashion I arrived at Turfan, the northern arm of the Silk Road. The heat in summer rises to 130° Fahrenheit, yet the temperature in winter is so bitter that vehicles can only be started by lighting fires under the engine sump, a risky procedure but regarded as routine.

In their heyday, the Silk Roads were famous thoroughfares, the numerous oasis-villages producing wines, melons and grapes which, side by side with religions, ideas, technologies and languages, moved to and fro between the Imperial Court at Ch’ang-an and the Ottoman and European empires. A German archaeologist travelling with me said that by the 8th Century Hindus, Jews, Nestorians, Manichaeans, Zoroastrians lived in great cities along the routes. They traded in cosmetics, rare plants, falcons, parrots, the occasional lion, and that marvel, the ostrich, first known as ‘great sparrows’, latterly ‘camel birds’.

Now the earthquake-scarred hills are destitute of all life, the cities gone.

To the north lies the snow-capped Bogdo-Ola, the ‘Mountain of God’, higher than anything in Europe. The division between arid desert and fertile land is as definite as that between shore and ocean. The first of the many garrisons I plan to inspect is only a matter of days ahead. The old warhorse in me sniffs the air and paws the ground. My mission can soon commence.

3am. The extremes of temperature have no effect on the repulsive insect life. In addition to mosquitoes, sand flies, scorpions, fleas and lice there are two particularly unpleasant kinds of spider. One is the jumping kind with a body the size of a pullet’s egg. Its jaws produce a crunching sound. The other is smaller, black and hairy, and lives in a hole in the ground. These are to be avoided. Their bite, if not lethal, is extremely dangerous. At night, I am surrounded by huge Turfan cockroaches. Their big eyes stare down at you, their long feelers try to attack your eyes. Finding such a creature sitting on my nose on awaking is enough to make any man vomit uncontrollably.

October 19. I am now the sole European in a small party camped the night by a large smugglers’ caravan of some forty transports laden with coral. The caravan is heading in the opposite direction to us, back, towards Irkeshtam and the Russian border. Coral is highly dutiable. We watched as the ponies were forced to swallow the coral. Once through the customs the donkeymen will delve through the ponies’ droppings to regain the smuggled lumps and beads.

October 21. Our Kirghiz horses are superbly sure-footed. Even on ice they keep their feet. They climb over boulders like mountain goats, or go unhesitatingly down steep paths cut like staircases. In this part of the world the distance from one point to another on the outward journey may be quite different from a return journey over exactly the same path. I came across this interesting fact on hiring mules and coolies for a diversion from an overnight encampment to an isolated fort. The charge levied for the one mile outward journey was tripled for the return journey on exactly the same track. With a patronising look the Chinaman explained the outward journey was downhill and therefore easy, but the same journey back was up a steep gradient and not at all easy. On level ground the distance of one statute mile equals just short of 3 ‘li’. By contrast, up very steep roads the same statute mile is called 15 li, and charged accordingly. A stretch down a river like the Yangtze might cost 90 li one way and the return journey up-stream a third more.

Late this afternoon our small and disparate band of travellers reached the end of a long valley. Leeches are plentiful on the lower slopes. Anticipating the arrival of monied ‘feranghis’ the local people readied several calico tents for us in the long, wet grass. They were armed with repeating rifles to defend their paying guests. We were supplied with various kinds of game hunted with falcons, mainly beautiful little red-legged partridges which run across the hillsides, and a large bird like Scotland’s capercailzie. The fare provided welcome relief from days of scraggy chickens or boiled mutton without salt, or the tins of sausages and soups brought from London.

October 23. At sun-up I joined a train crossing rough territory for about 50 miles in the right direction. A short way into the journey it pulled into a small station to replenish water and coal. Word got out among the two or three Europeans aboard that we would be there long enough to stretch our legs.

I stepped on to the platform and before long a most amusing sight presented itself. Coming at a lick down the dusty road towards the station entrance was a wheelbarrow covered with yellow silk, pushed by a panting porter and preceded at a trot by several coolies waving yellow banners. Leaning out of the wheelbarrow at a dangerous angle was an old man adorned with the longest white beard imaginable, so long it was in danger of catching the legs of the banner-bearers and upending them.

The soothsayer’s flamboyant clothing was a curious mix of Manchu and Han attire, the flowing sleeves displaying the depredations of moths and their caterpillars which had eaten out some considerable patches. His head was shaved except for the long pigtail known as a queue. The eyeglasses clamped on the Chinaman’s pock-marked face were the thickest I have ever seen, slices of smoky quartz crystal polished until translucent. They completely enclosed his eyes, like Victorian railway glasses worn in open carriages to protect the eye from funnel smoke and sparks.

Two further coolies at the unusual transport’s sides held up a red woollen cloth umbrella in a cylindrical shape, like the half of a drum. A retainer brought up the rear, carrying his master’s water-tobacco pouch, a small hat and a clothes bag.

The porter brought the wheelbarrow and its cargo on to the platform at a run and dropped it thankfully, sweating heavily. Out stepped the theatrical fortune-teller. The banners were held up in a semi-circle behind him by the attendants. Around his waist was a silken belt with dragon and tiger hooks of a white stone from which were suspended a watch, a fan, an ornamental purse and a small knife. I was astonished to see he was afflicted with the hereditary condition known as thumb polydactyly, both hands having full duplication of the thumb including the first metacarpal. Many inhabitants, whether Manchu or native Chinese, have a deformation of some sort, a goitre, a strange squint, an unsightly dinge in the forehead, even one side of the face completely different from the other. His smile displayed another hereditary affliction: four or five of his teeth ran together in one piece, like a bone.

The spectacles made it difficult to place from which part of China his ancestry originated. The predominant Han have flat faces and noses. People originating in the north are often heavier and taller with broader shoulders, lighter skin, smaller eyes and more pointed noses than the people south of the Huai River–Qin Mountains line.

At my side, delighted with this display, was a fellow European, the same German archaeologist. He had good knowledge of Mandarin, and more to the point, Chinese logograms.

To my horror the fortune-teller singled me out. His voice was unexpectedly shrill.

‘I am your humble servant from Chin-Hwa,’ my new companion translated, adopting the same sing-song voice.

The German pointed at the fortune-teller and asked, ‘Surely, Doctor Watson, you aren’t going to lose the chance to know your future - and for so little expense!’

He translated the logograms -

Foretelling any single event . . . . . . . . 8 cash

Foretelling any single event with joss-stick. . . . . . .16 cash

Telling a fortune . . . . . . . . . 28 cash

Telling a fortune in detail . . . . . . . 50 cash

Telling a fortune by reading the stars . . . 50 cash

Fixing the marriage day . . . . . . . fee according to agreement

To the general satisfaction of other passengers on the platform I succumbed. I opted for ‘fate calculating’. The fortune-teller asked for the hour of my birth, the day, the month and the year (to which for some reason he added a further year). The archaeologist acted as language interpreter. He also explained the seer was writing my answers down in particular characters to express times and seasons. From the combinations of these and a careful estimate of the proportions in which the elements gold, wood, water, fire, and earth made their appearance he would make his predictions.

In return for a ‘shoe’ (a string of 50 cash) I received the following: ‘Your present lustrum is not a fortunate one; but it has nearly expired, and better days are at hand. Beware the odd months of this year: you will meet with some dangers and slight losses. Danger can be ameliorated by offerings at the Temple of Boundless Mercy. Two male phoenixes will be accorded to you. Fruit cannot thrive in the winter (he had arbitrarily decided to place my birthday in the 12th moon). Conflicting elements oppose: towards life’s close prepare for trials. Wealth is beyond your grasp; but nature has marked you out to fill a lofty place.’

Certainly the ‘Wealth is beyond your grasp’ had the ring of truth. At the last prediction, ‘nature has marked you out to fill a lofty place’, the considerable number of locals and the station-master gaping at the proceedings broke into raucous laughter and hoorays. The fortune-teller’s retainer ran around handing out visiting cards.

The train’s whistle gave a warning blast. With a wide smile exposing the fused front teeth the soothsayer took the 50 cash and waved me into my compartment, repeatedly bowing, chattering in Chinese (Mandarin with a northern rhotic accent, with a few archaic, out-of-context English words thrown in, according to my knowledgeable German fellow traveller).

As the Chinaman leaned forward to close the carriage door I caught a split-second sight of a banner through the very edge of one of his glass lenses. Curiously, there was no magnification, reduction or compensating distortion. The appearance of the logograms puzzled me. They were quite unchanged.