The same year that British industry so proudly displayed its iron virtuosity to the world, an ironmaster outside tiny Eddyville, Kentucky, was hiding in the woods from his wife, who thought he was mad, and from other detractors, who thought him a fool. He was dirtying his knuckles trying to invent a process that would make the proud British iron of the metal’s golden age forever obsolete.

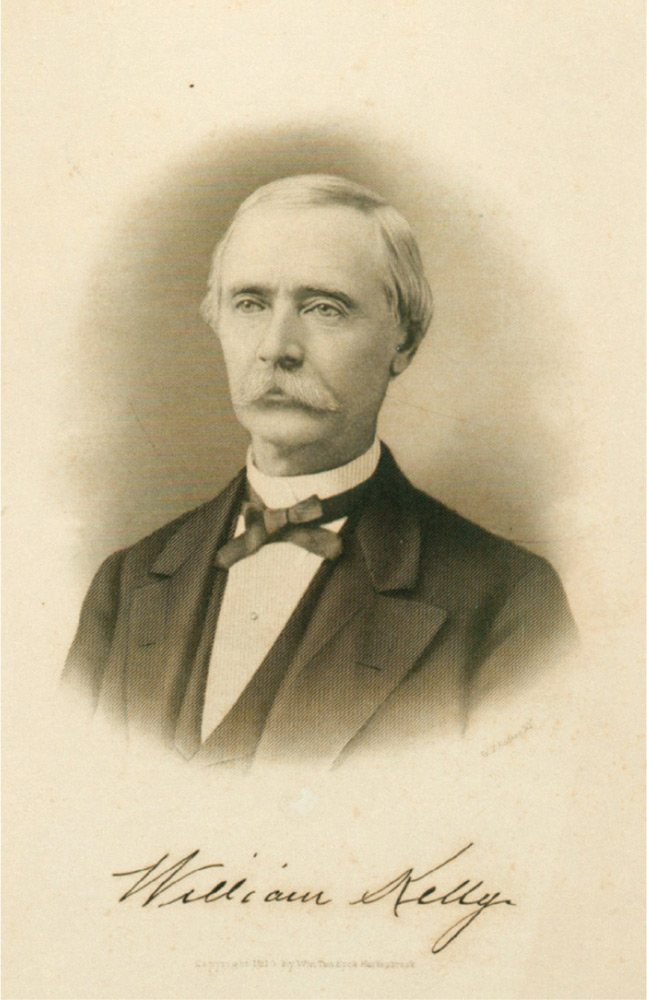

William Kelly of Kentucky discovered a rapid means of converting pig iron to steel but lost the posterity competition to Henry Bessemer.

The ironmaster was William Kelly, born in Pittsburgh in 1811, a student of metallurgy, as it was then understood, and the owner of an ironworks in the west Kentucky hills. He had bought the works in Eddyville and left Pittsburgh in hopes of making his fortune, but he soon came across virtually the same problem as Abraham Darby had 150 years before in England. His woodlands were denuded and he needed a way to save fuel. The hearth Kelly used was the pre–Henry Cort type; that is, he made wrought iron by covering pig-iron lumps with charcoal, igniting the charcoal, waiting for the heat to burn out some impurities in the pig iron, and then beating out most of the rest with a hammer, an onerous and lengthy process. One day, Kelly saw some brightly glowing molten pig iron in line with the blast of air he used to make the charcoal hotter. He knew that pig-iron impurities included carbon and other elements, and that at a sufficiently high temperature these substances combined with oxygen, the chemical reactions producing heat. So the idea struck Kelly that if he raised the temperature of the pig iron sufficiently, then all he would have to do would be blow air on it. The carbon and other elements would simply fly off with oxygen in self-perpetuating, heat-producing reactions—the pig iron getting hotter and hotter and staying liquid—until there were no impurities left. The result would be a nearly pure iron in liquid form. No one had ever made pure iron before, and its potentials were considerable. With pure iron as a liquid, Kelly could add back in small amounts of slag to make wrought iron or the correct amount of carbon to make steel.

When he told his wife about “air-boiling” to refine pig iron into pure iron, she thought him mad and sent for the doctor. Other ironmasters told Kelly that blowing air on liquid pig iron would only make it colder and had some laughs at Kelly’s expense. So Kelly was forced to retreat to a secluded part of the shrinking woods that remained to him and worry into existence a converter that would refine pig iron into wrought iron without either the monstrous hammering of the ancient process or the strenuous stirring of the Cort process—and, eventually, to make steel. He built his first machine of any merit in 1851.

THE VAST COUNTRY in which Kelly worked, the country that in the year of his death a scant thirty-seven years later was the mightiest industrial nation the world had ever known, had had a checkered career in the iron business. The natives who called the land home when Europeans first appeared knew nothing about smelting or casting even the simplest metals.

But, as Sir Thomas More had written in Utopia at the beginning of European exploration across the Atlantic, “Man can no more do without iron than without fire or water,” so the European settlers of America sweated to raise new ironworks. The first of these after the great Falling Creek Massacre in Virginia rose along the Saugus River north of Boston in 1642. Early in the following century, George Washington’s father became a partner in another concern further south. These early ventures were meant to supply customers and line pockets on both sides of the Atlantic. From New England to the Carolinas, so-called iron plantations using the labor of slaves, indentured servants, or natives, self-sufficient in just about every way, marked out for themselves thousands of acres of woodland. The British helped establish many of them and pressed hard to send skilled ironworkers to the New World, a decision that would cause their descendants no small grief.

A water-wheel bellows stokes a Saugus, Massachusetts, blast furnace. Men dumped in materials from an uphill ramp.

By 1750 these scattered ironmaking settlements were making one-seventh of the world’s pig iron and turning a good bit of it into finished tools and utensils. Meanwhile, the British, slow to convert from scarce charcoal to abundant coal, could not dominate the world market as they had hoped. But, like good mercantilists, the British wanted their colonies to behave like colonies—that is, to send cheap raw materials to the mother country and to purchase back more expensive finished articles. So they passed a law allowing the free import into Britain of colonial pig iron and prohibiting the construction of any new ironworks in the colonies that made finished goods. The colonials bristled in a way that set a pattern for dissent in the next twenty-five years. They also built new ironworks anyway, setting the precedent for breaking British law, an example not lost on the younger generation.

When open revolt finally ignited in 1775, most ironmasters and workers chose the Patriot side. Five signers of the Declaration of Independence and three important generals were directly associated with the trade. Iron was vital to the Rebel cause, as well the British knew. A good many battles ensued when redcoats marched out to lay waste to munitions-making ironworks, one of which was Valley Forge, a small iron plantation. But despite repeated assaults, the iron industry of the nascent country held on long enough to assure independence.

However, after the war, American production slumped badly while British imports soared. Alexander Hamilton pleaded for government policies that would foster industries, but his counsel went unheeded for decades. In the fifty years after the turn of the century, the British iron trade concentrated and grew, while the American industry remained largely rural, divided, and puny. In 1850, even though the United States population was roughly equal to that of Britain, it produced one-fifth as much iron.

Holed up in the woods, William Kelly could not make the quality product he coveted and achieved no breakthrough. But while he was tinkering, the Crimean War erupted in southern Russia. A self-styled professional inventor devised a new kind of spinning artillery shell to sell to the Europeans but found that because the standard cast-iron cannons were not up to shooting it, he would have to invent a better cannon barrel as well. So the inventor, Henry Bessemer, a broad-browed man with no formal education but an inclination toward tinkering (an improved typesetting machine and sugarcane crusher were two early efforts), set out to make a better cannon barrel of steel. Using Huntsman crucible steel was out of the question—it was too costly and difficult to make in large quantities—so he realized he had to come up with a whole new method. Bessemer never shipped a cannon to the British army before the end of the war, but he changed the world.

Working near a furnace one day, the fortyish Bessemer by chance noticed the same thing Kelly had—that an air blast alone could increase the temperature of hot pig iron. In his experiments, he attempted a way to pour liquid pig iron into a four-foot-high vessel and then blow air in through the bottom. On his first try, all went smoothly for ten minutes, and then a huge white flame leapt out, followed by sparks, eruptions, and flying liquid metal. Neither Bessemer nor his helpers could approach the roaring and sputtering machine for ten more minutes until the conflagration had died down. But what they found when they poured out the product was a nearly pure, almost totally decarburized iron. All they had to do was add back a touch of carbon and they had cheap steel. Bessemer claimed victory in 1856.

Immediately British ironmasters took up the process and just as quickly declared Bessemer a fraud; the steel they made following his instructions was hopelessly brittle. As it turned out, Bessemer had been both ignorant and lucky—he had used pig iron very low in phosphorus, a chemical additive that made steel brittle. Phosphorus did not burn out in the conflagration, and when the British ironmasters followed Bessemer’s lead they produced a breakable product. This was partly Kelly’s problem also—the harmful phosphorus did not burn out as the carbon did when air was blown through the hot liquid pig iron. Bessemer, however, solved the problem by importing low-phosphorus ore from Sweden and opening new mines in Britain that produced low-phosphorus ore. Then, when he had refined his machine and made some adjustments, he could truly proclaim the age of cheap steel. Huntsman’s method produced about sixty pounds of steel in two weeks; Bessemer’s produced five tons in twenty minutes. Bessemer began selling steel at one-tenth the going price. James Nasmyth, Scottish developer of the steam hammer, held aloft a small piece of Bessemer steel and said, “Gentlemen, this is the true English nugget; its commercial importance is beyond belief.”

An 1875 engraved illustration shows the Bessemer converter, at left during a “blow” and at right pouring out the finished steel.

When Kelly heard of the Britisher blowing air through liquid pig iron, he rushed out of the woods and registered a patent on his own process. It held in America, although he needed some Bessemer patents on machinery and refinements to make the process work successfully. Consequently, he lost out in posterity’s selection of a name for the process—it went to the Englishman.

But the name hardly mattered. For the next fifty years, the best show in steelmaking, or in any industry, was the “blow.” A converter, as the steelmaking machine came to be called, evolved into a twelve-foot-high, black steel vessel resembling an egg with an open top. It tilted to allow molten pig iron to be poured in and again for pouring the finished product out. During the time in between, when the metal egg was straight up, with liquid pig iron inside and the air blast turned on, it became a volcano. First, red flames lashed out of the top as the silicon in the pig iron burned away. Then for ten minutes a brilliant white flame, sometimes thirty feet high and full of sparks, roared toward the factory ceiling as the carbon burned away. Men slunk back as if it were a dragon.

This cacophonous vessel of the horrible breath, this spewing, blackened Satan’s egg, débuted in America in a propitious year—1865. It was the year of the triumph of urban over rural, of factory worker over field hand, of capital over land, of entrepreneurial spunk over sluggish paternalism. It was also the year that thirty-year-old Andrew Carnegie founded the Union Iron Mills of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

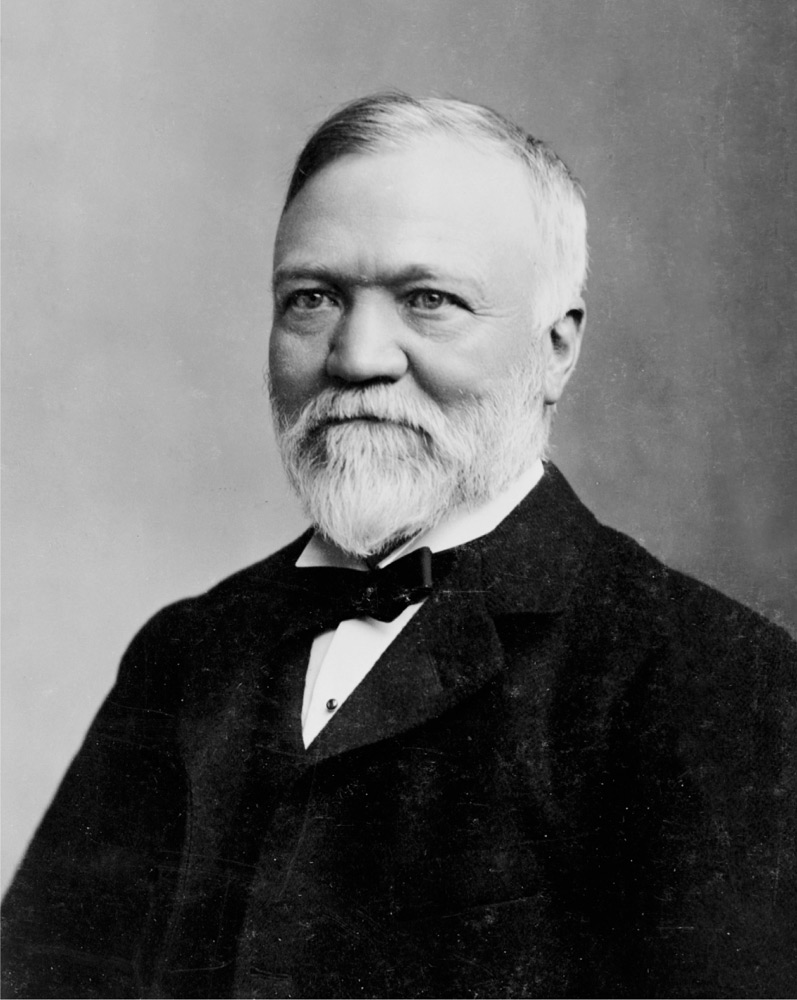

The burgeoning, mercurial world of the postbellum North spawned many a Dauntless Dick, but none was spunkier and shinier—or more successful—than this five-foot-three-inch Scot immigrant boy. One day Carnegie would be called “robber baron” and “malefactor of wealth,” but in true fairy-tale fashion, his origins were humble—and radical. His mother and father, both working people, were active in Scottish politics that championed workers and protested privilege as then practiced by the monarchy, aristocracy, church, and private education.

Forced from Scotland by unemployment in 1848—the elder Carnegie was a handloom weaver put out of work by mechanization—the Carnegies settled in a slum section of Pittsburgh called Slabtown. The father foundered, but the son flourished. He saw nothing but opportunity in this land of the politically free, and he went from job to job eager to please and be recognized. Like Benjamin Franklin a hundred years previous, he wrote notes of self-improvement to himself, and soon he became the protégé of an important official on the Pennsylvania Railroad. He made some spectacular investments, organized a bridge-building company, and then, in 1865, founded the Union Iron Mills to supply the bridge-building company. By 1868 he was making fifty thousand dollars a year from his investments and he wrote to himself: “Make no effort to increase fortune. … Cast aside business forever except for others. … The amassing of wealth … is one of the worst species of idolatry. … I will resign from business at Thirty-Five.”

But it was not to be. He became fascinated with helping to build the first great bridges across the Mississippi River and with raising the money for them by visiting the capital markets of Europe. On one of his trips to England, in 1872, he visited a Bessemer plant in Sheffield. He realized there that what someone in America had to do was to take advantage of the economies of scale—to get really big. Carnegie returned to Pittsburgh and convinced his partners to build the world’s most modern and efficient Bessemer steel plant, which they did, right on the banks of the Monongahela River where the British general Edward Braddock had been so rudely defeated in the previous century, thanks in part to Indian allies of the defending French forces. In another deft move, calculated to help sell his new plant’s principal product—railroad rails—Carnegie named the works after his friend, Edgar Thomson, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Carnegie had caught America at precisely the right time. Up through the Civil War, rails for railroads had been made of iron; these were prone to splitting, often with tragic results, and for safety reasons were meant to be replaced twice a year. Bessemer steel rails, on the other hand, could last ten years.

Andrew Carnegie in the 1890s. Twenty years before, he had seen the virtue of making mills larger than before.

Carnegie, as majority stockholder in the fledgling mill, hired the best engineer in the country to build it and the best superintendent to run it. He pioneered a cost-accounting system. His business philosophy was relatively new: cost control, low markups, low prices, and high volume. “Take sales orders, run full” was a favorite dictum. “Watch the costs, and the profits will take care of themselves” was another. He tore down new buildings if he learned a better design could lower his cost per ton. The Carnegie enterprises grew and prospered.

IN EUROPE, too, steel mills were rising like metal fungi, especially where rivers crossed coal fields or iron deposits. Across the mineral-rich Midlands waist of Britain, steelmen raised their blast furnaces and converters. In France, steel companies concentrated near the immense iron-ore beds of Lorraine in the east and the coal fields of Le Creusot further south. But it was in Germany that the largest steel industry in Europe was spreading along river valleys, transforming the country from a near-feudal patchwork of rural fiefs into the most powerful industrial nation east of the Atlantic.

The mightiest of the new German concerns rose in the city of Essen, near the confluence of the Ruhr River and the Rhine, on top of huge coal deposits. It was here that in 1811, the year William Kelly was born, a man named Frederich Krupp had built a small shop in hopes of cracking the secret of Sheffield steel and winning the four-thousand-franc prize promised by Napoleon. He failed and died in his thirties, a broken man. But Alfred, his fourteen-year-old son, inherited the works and immediately set about to restore the family name.

Alfred was a bit of a crank. Skinny, quixotic, and brilliant, he was inspired by the odor of horse manure (later in life he built his home office over the stables) and the notion of perfection. After the secret of Sheffield crucible steel became common knowledge in the 1840s, Alfred realized the future lay in producing high quality in large quantity. So with Prussian drillmaster fervor, he strove for both. He awed crowds at the Crystal Palace with the world’s largest block of crucible steel—4,300 pounds. He also won admiration for a small, but exquisitely crafted, crucible-steel cannon.

In the late 1860s, Krupp grew rich making railroad wheels, thousands of which sold in America—three rings symbolizing railroad wheels became the Krupp logo. In the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Krupp’s crucible-steel cannons smashed the French army, whose artillery was made of bronze. Thanks to Krupp, Bismarck could build a united Germany around Prussia. Thanks to Bismarck’s war, Krupp received terrific publicity, and from around the globe orders for new guns were dispatched to Essen. Much of the fighting had raged across the Alsace-Lorraine region of northeast France, where three-fourths of French iron ore and machine shops lay. Germany seized most of Alsace-Lorraine as a prize of victory; the province, with its mineral wealth, was a source of contention between the two countries thereafter.

Like Carnegie, Krupp made a habit of using depression years to expand, not retrench. He built Essen into the largest industrial center in Europe—really a gigantic company town, because Krupp, the sole proprietor, owned the housing, hospitals, schools, and even the Bibles. He pioneered health and pension plans. But he demanded complete loyalty from his Kruppianer, mostly fresh from the farms and working exhausting hours at his shimmering furnaces. He hated universal male suffrage, and unionism was anathema. His works grew and prospered, and he linked his fortunes closer and closer to Germany’s Kaiser.

In 1879, Krupp’s prospects were boosted even higher, this time from an unlikely source—an English police court clerk. He was Sidney Gilchrist Thomas, twenty-eight years old and a dabbler in chemistry. At a lecture one day, young Thomas learned of a problem that had baffled a generation of scientists and also that “the man who eliminated phosphorus in the Bessemer converter would one day make a fortune”—phosphorus having remained a nuisance because it was in so many ores. Thomas, in good English fashion, established a laboratory in an old shed and set out to crack the nut. After some tinkering he figured that if the lining of the converter were changed from one that was chemically acid to one that was chemically basic and that if a basic flux such as lime were thrown in, then the phosphorus would combine with chemicals in the lining and become trapped in the flux as part of the slag, undesirable and unincorporated elements that floated on top of the heavier iron below and could be easily separated. When he tried this method, it worked perfectly.

Thomas’s new process was the answer to steelmakers’ dreams—they could now make as good steel with the abundant and cheap phosphoric ores as with the rarer expensive nonphosphoric ones. Aside from the immediate savings to steelmakers, the process also hastened the acceptance of a new kind of steelmaking furnace, one that could make better steel than Bessemer’s converter and in quantities four times as great.

This was called the open hearth, developed by combining the ideas of a German immigrant to England named Siemens and a French father-son team named Martin. Basically it was an improvement on Cort’s furnace—men laying cast-iron bars or pouring liquid pig iron on the floor of a long narrow hearth. But the Siemens-Martin process used recycled heat to increase the temperature of the incoming flame so much that the iron stayed liquid even after the carbon had burned out. Consequently, steelmakers could add or subtract ingredients at will to make a high-quality steel. The open hearth could even melt scrap steel, thus reducing the iron-ore cost.

There were two other great consequences of the process by Thomas, who did indeed make a fortune but died of overwork at the age of thirty-five. One, oddly enough, helped farmers: the slag produced, being rich in trapped phosphorus, could be pulverized and thus became a prime resource for the nascent artificial fertilizer industry. The other gave boosts to France and Germany, but especially Germany. The huge iron-ore fields of Alsace, Lorraine, the Ruhr, and the Saar—all very close to the border between the two countries—were high in phosphorus and suddenly much more acceptable to steelmakers. So for the time being, Germany, and especially Krupp, was going to feast. Not only were the Ruhr and the Saar solidly German, but so—because of the war prizes—were Alsace and much of Lorraine.

IF GERMANY WAS LUCKY, America was blessed. A thousand miles northwest of Pittsburgh, a few men bushwhacked through forest, cohabited with Indians, and fended off bears in a land that Kentucky statesman Henry Clay had once suggested was so far from civilization as to be “beyond … the moon.” Still, Americans had always thought there was wealth there, in the Great Northwest. This vast rolling land around and west of Lake Superior first attracted fur trappers. Next, missionaries sought to spread their religious teachings via canoes, and then prospectors tramped about looking to line their pockets with gold, silver, and copper. None thought much of where the real material wealth lay, not even the man credited with discovering it. He was William A. Burt, who in 1844 was leading a surveying party of white men and Indians. One day his compass needle began spinning in its case as if bewitched. Burt soon realized he was standing on acres of iron and he considered it a nuisance.

The following year, Philo Everett, a spunky south-Michigan prospector, thought the iron might be worth pursuing and so headed north. He traveled on foot and by boat for six weeks, “often wet for days.” With the help of an Indian woman named Full Moon, and then her uncle, Marji-Gesick (also known as Moving Day), he struggled to reach their mystic mountain, one the Indians said drew lightning out of the sky and where lightning danced even among the rocks. As the party approached, the Indians held back in fear and merely pointed. Everett tramped up without them. The promontory was a massive mound of iron ore.

For the next fifteen years, men staked claims, jumped claims, froze to death, set fire to the cabins of rivals, sank test pits, cut mineshafts, hauled ore in wheelbarrows, built crude railroads, went bankrupt, went crazy, or just plain held on. They rolled ore rock down to the hamlet of Marquette (really just a wharf they built on Lake Superior), sailed it east to Sault Ste. Marie, portaged it around the rapids in the river to Lake Huron, and sailed it farther south again. They began bringing ore down in quantity just as the Northern armies were organizing for the Civil War; four years later at Appomattox Court House, Robert E. Lee wrote to his ill-clad, ill-fed soldiers that they “had been compelled to yield to overwhelming … resources.”

It was 1868, however, before anyone thought of carefully analyzing the Lake Superior ore. Chemists found that it was remarkably free of phosphorus, perfect not only for the Bessemer process but for the Thomas process and the open hearths, too. That spurred a new rush of eastern capital and hairy prospectors to the North Country, a rush that would make more millionaires than the California 1849 gold bonanza. Miners came from Wales, England, Sweden, and Finland. Then came the “miners of the miners.” Daisy Redfield and her rapturous house of white slaves set up in one town; Old Man Mudge, with a staff that included his daughter, protected his sin-house from the pure with chained wolves; and one sink of iniquity enlisted the services of a trained monkey to lift wallets and watches. America was launched on her most colorful age.

THE BESSEMER CONVERTER and the Siemens-Martin open-hearth furnace, directly responsible for the ruckus on the Lake Superior frontier, were also changing the rest of America and the world forever. Because of them, North America, Europe, and India were being laced with rails, not only opening the resource-rich interiors of these lands for commerce but also giving their peoples the fastest transportation and freight handling they had ever known. Great steel suspension bridges began spanning rivers and valleys. Navies and passenger liners turned from the wooden past to steel-hulled behemoths. Architects designed ever-higher buildings with inexpensive steel girders and beams. Subways of steel began burrowing beneath cities. Food manufacturers discovered they could preserve their products in steel cans. Farmers bought machinery of steel; they fenced prairies and plains with steel barbed wire.

Bessemer converters and open hearths even made a revolution on the factory grounds. Because they could accept much more pig iron than any steelmaking machines before them, they required bigger blast furnaces. And because the hotter the pig iron the better when it was poured into the steelmaking furnaces, it made sense to build the blast furnaces near the steelmaking machines. Ironworks and steelworks sprouted in America where rivers provided cooling water, transportation both into and out of the plants, and effluent disposal, and where either coal or iron ore or both were near. Besides the Monongahela Valley at Pittsburgh, mills cropped up on the Lehigh and Conemaugh Rivers in Pennsylvania, at Bethlehem and Johnstown; along the Mahoning and Cuyahoga Rivers in Youngstown and Cleveland, Ohio; and along Lake Michigan south of Chicago. Later, the Lackawanna Steel Company moved out of Scranton, Pennsylvania, to the shores of Lake Erie south of Buffalo, New York. Though lacking major water routes, ironmaking sprouted in Birmingham, Alabama (named for the English industrial city), where iron ore, coal, and limestone deposits were close to rail lines. Some of these mills had started as ironworks before the Civil War; now all were getting into the steel business and growing larger.

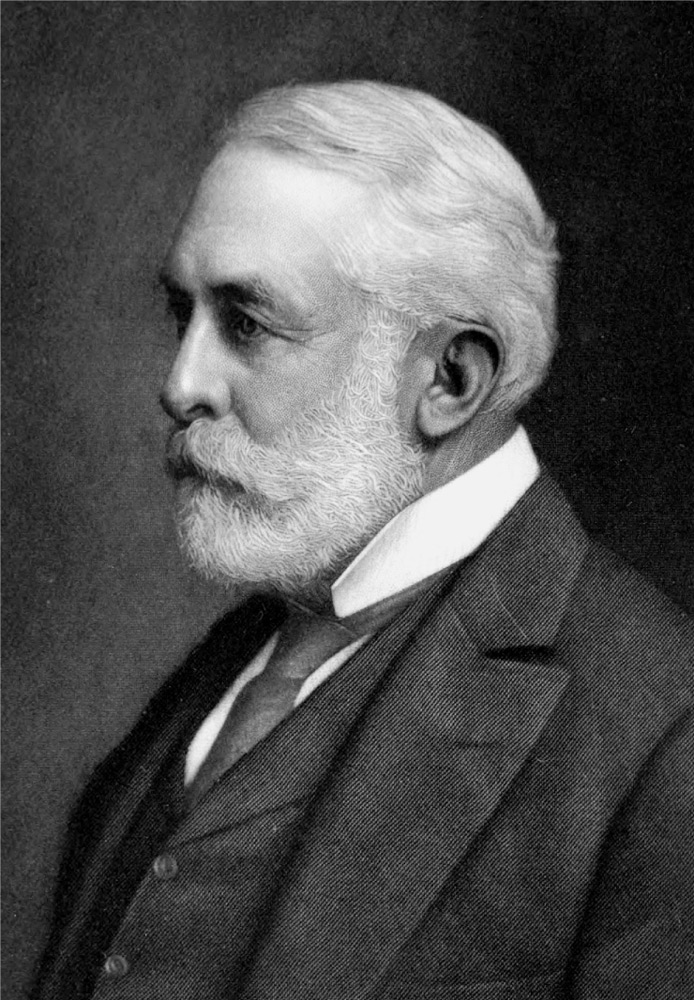

The next step for a company with blast furnaces and steelmaking machines was owning natural resources. As usual, it was Andrew Carnegie who took the plunge in the biggest way. He bought a majority interest in the H. C. Frick Coke Company, just up the Monongahela and Youghiogheny Rivers from Pittsburgh, which controlled almost limitless coal of the superior consistency needed to make the coke that smelted iron ore in blast furnaces. Carnegie also acquired the services of Henry Clay Frick himself, a thirty-two-year-old farmer’s son and self-made millionaire who was as serious about business as a bloodhound about tracking.

Carnegie was not content merely to integrate vertically. He well understood the economies of scale, and in 1883, a depression year, he bought a brand-new plant from squabbling rivals a mile down the Monongahela at a place called Homestead. Anticipating the eventual decline in the demand for rails, he converted its product to structural shapes for skyscrapers. In 1890, he bought another brand-new mill, called Duquesne, up the Monongahela River. With it, Carnegie’s empire could churn out half as much steel as the entire British industry.

America could have done much worse than having Andrew Carnegie as its foremost industrialist and richest man. He was not above some dirty tricks, but compared to many of his contemporaries, he set a sterling example in the business world. He deprecated gambling, philandering, stock watering, collusion, monopolies, and, after 1872 anyway, stock speculation. He paid far less attention to profits than to cutting costs and increasing efficiency. He was fond of the arts and literature, and in the 1880s he set about writing articles and books, gleanings from which have guided and goaded American businessmen ever since.

One famous essay, “Wealth,” roused a furor. “I would as soon leave my son a curse as the almighty dollar,” he wrote, debunking inherited largess. “[T]he duty of the man of wealth,” he continued, was to “set an example of modest, unostentatious living … to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds which he is called upon to administer” for the public good.

In Triumph of Democracy, Carnegie lambasted aristocracy and championed the egalitarianism of his adopted land. He hailed material progress and extolled the capitalist as the agent of progress, because it was the capitalist who worked under the law of competition and lowered the price of goods for everyone.

In reality, Carnegie had more trouble living up to his aphorisms than he did casting them. As his mills and those of his rivals grew, more and more men sweated in larger and larger corporations until they became strangers to the men who were lucky and shrewd enough to be owners. Workers made an average wage of $2.50 a day (about $60 in 2015 dollars), while the few who claimed title to the machines, buildings, and natural resources pocketed millions. Carnegie could hail political equality, but he was little help in preventing the broader social equality that America seemed to embody from slipping away.

Henry Clay Frick joined his coal properties to Andrew Carnegie’s steel works and made Pittsburgh a capital of steelmaking.

Moreover, the work in the mills was exceptionally hard. Generally the men labored seven twelve-hour days every week. Heat in summertime made the mills hellish. The machines, recent inventions themselves, caused ghastly accidents, about which the men grew fatalistic. Workers began in their teens, and few, including plant managers, could stand the pace twenty years later. In the fierce competition of the day, they were driven relentlessly. If they gave out, there were always other farm boys or immigrants willing to take their places.

The mills proved fertile ground for the embryonic and struggling labor unions, mainly associations only for skilled workers. As the numbers of workers grew in the ever-larger mills, it became increasingly obvious that they could not all rise to be owners—as many of them may have thought in the 1850s and 1860s—and that for their own protection they had better think of themselves less as individuals and more as a group. The great success of the industry was obvious for all to see, but so too was the burgeoning social inequality. The pendulum, having swung one way, was bound to provoke a force that would pull it the other, and unionism was to be that force.

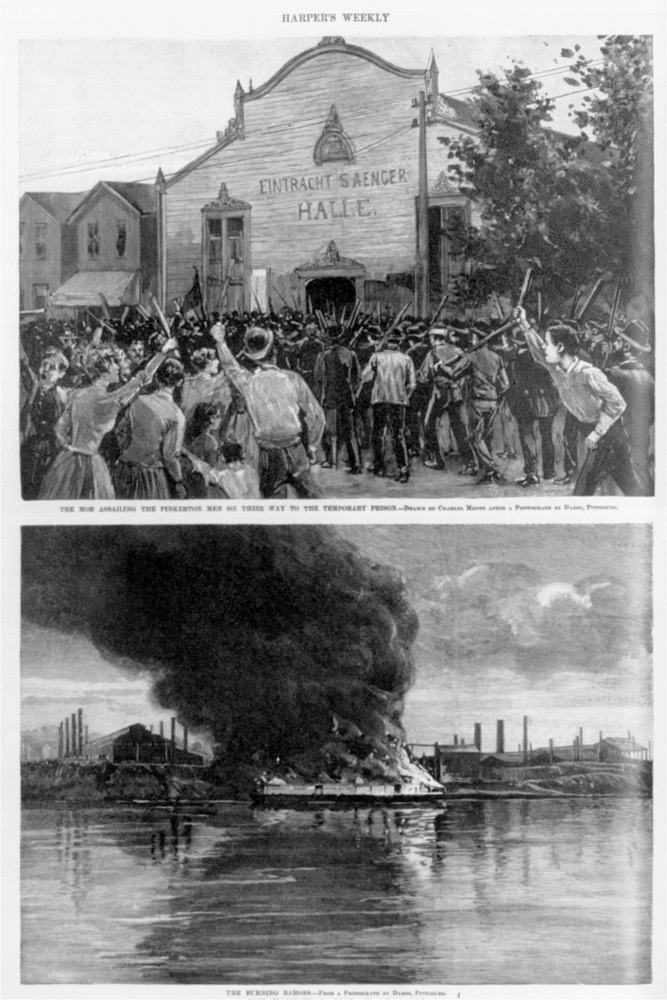

First blood was spilled at the gates of the Carnegie Steel Company, Homestead Works, in 1892. Henry Frick, tough as shoe soles and president of the company at the time (though subordinate to chief stockholder Carnegie), wanted to break the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers at the Homestead plant, where union membership only numbered 1,800 out of 3,800 workers, and to make Homestead, like all the other Carnegie plants, nonunion. Carnegie had proclaimed that he supported the rights of unions, but he turned the situation over to Frick and went on a vacation to Scotland. Frick proposed unreasonable demands during negotiations, the union resisted, and Frick closed the plant. The union persuaded all Homestead workers to strike, and because Homestead, the steel plant, was surrounded by Homestead, the town where the workers lived, the plant was virtually sealed off from management. Frick could have sat it out as Carnegie had hoped, but instead, after trying to use local officials, he hired agents from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to do his dirty work. The Pinkertons, mostly recently down-and-outs themselves, motored up the Monongahela to seize the plant so that management could reopen it with recalcitrant union men and scabs. (This clash served as the origin of the word fink, meaning industrial spy or strikebreaker—a corruption of Pink, for Pinkerton.) The workers defended the steelworks in a day-long battle that left ten Pinkertons and workers dead.

National Guardsmen marched in, and public sentiment railed against the owner-capitalists until nineteen-year-old immigrant anarchist Alexander Berkman from New York City walked into Frick’s office and shot and stabbed him. The curmudgeon survived, even wrestled Berkman to the ground, and finished his day’s work before letting the ambulance take him to doctors for treatment of his wounds. Because of Berkman’s assassination attempt, sympathy turned against the union even though it had nothing to do with the assassin. In the end, Carnegie got a union-free empire, and because all other steel companies generally followed Carnegie’s lead, the industry remained nonunion until the 1930s. The workers fed on hopelessness, and in their mills they felt more tightly bound to one another than to any man who owned a piece of the means of production.

Harper’s Weekly depicted angry Homestead steelworkers accosting Pinkerton men and burning their barges. Library of Congress

IN THE SAME YEAR that America was foolish enough to spark one of her darkest hours in the Homestead Strike, she was lucky enough to trip over one of her greatest blessings. Up on the Minnesota frontier, some brawny woodsmen known as the Merritt Brothers kicked over the pine needle forest floor and revealed one of nature’s freaks—the gigantic Mesabi iron-ore vein. It lay under only inches of topsoil and was so soft it could be scooped up with a spade. Once the trees were removed, eight men with a steam shovel could take out more iron ore in one hour than hundreds of miners in an underground shaft all day. They could reduce the price of ore at the minehead from three dollars a ton to a mere five cents. And the ore was incredibly pure.

The Merritts borrowed heavily to buy equipment and build a railroad from their properties to Lake Superior. The Panic of 1893 caught them too short of cash and orders. That is when John D. Rockefeller stole a march on Carnegie and “rescued” the Merritts by buying them out and thus gaining control of the world’s best iron ore. Such a coup horrified steelmakers because they realized that, being thus positioned, the viperous Rockefeller could try to do with steel what he had done with oil—that is, monopolize it. Actually, “Reck-a-fellow,” as Carnegie liked to call him, never wanted to enter the steel business, but Carnegie took no chances and made a deal with the oil man that gave leasing rights of Rockefeller ore lands to Carnegie companies. Carnegie then had his natural resources locked up—coal from Frick’s properties and iron ore from Rockefeller’s—and, as a commentator wrote at the time, the deal “complete[d] the last link in a chain which [gave] the Carnegie Steel Company a position unequalled in the world.”

Carnegie was demonstrating how heavy industry could make acquisitions while integrating backward or forward yet still maintain high efficiency. He had imitators, and they came gunning for him. The business climate of the time was an odd blend of cutthroat competition calculated to ruin rivals combined with a willingness at other times to collude with those same rivals, allowing prices to stay up and thus letting all survive. In the 1890s, Wall Street financier J. Pierpont Morgan, Chicago lawyer Elbert Gary, flamboyant businessman John Warne “Bet-a-Million” Gates, and several others had put together a few combinations of steel companies. One of these, Chicago-based Federal Steel, was large enough to make half as much steel as Carnegie, and the others—made up mainly of companies that bought raw steel from Carnegie for shaping finished products such as pipe and wire—were now threatening to integrate backwards, make their own raw steel, and thus cut out the Little Scot altogether.

Carnegie saw the threat immediately, and his old competitive blood flowed fast again, as in his youth. He threatened to make new mills for finished products that would run rings around the other combinations. Morgan and Gary were mortified; they hated competition, which they saw as leading to duplication of plants, the progenitor of overcapacity, waste, cutthroat pricing, and ruin. Besides, they saw a contest with Carnegie as one they might not win, and so they figured the only way to stop Carnegie was to buy him out.

In this they were lucky, because Carnegie, then sixty-five, was hearing his old self whispering, “Cast aside business forever except for others.” Carnegie’s new and affable president, thirty-eight-year-old Charles M. Schwab (Frick having resigned as president in 1895, after squabbles with Carnegie, and turning to such interests as collecting art), knew of Carnegie’s sentiments and had a secret talk with Morgan. Through an all-night session in the mahogany-paneled Morgan library, surrounded by priceless paintings, Morgan, Gates, and Schwab conceived a gigantic conglomerate that would merge Carnegie with other combinations and that would be called the United States Steel Corporation—if only Carnegie would sell.

The man who might be able to convince Carnegie was Charlie Schwab. Schwab was a steelman on the rise. Born into a family of German Catholics in central Pennsylvania a year before the Battle of Gettysburg, he grew up in Loretto, not far from where the Pennsylvania Railroad climbed the Alleghenies on its route from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. After two years at St. Francis College in Loretto, Schwab set off for Pittsburgh, where he was hired at Carnegie’s Edgar Thomson Steel Works as a stake driver in the engineering department. He was an eager, bright, and ambitious employee, studying steel chemistry at night. Confident and cheerful, he was promoted often; he became the superintendent of Carnegie’s Homestead Works and then general superintendent of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works in 1889 (thus missing the Homestead Strike debacle of 1892). In 1897, at only age thirty-five, he was picked by Carnegie to be president of Carnegie Steel.

To put Carnegie in a good mood, Schwab played golf with the Little Scot and intentionally lost, then presented Morgan’s proposal, including the part that said Carnegie could name his price. Carnegie did: nearly half a billion dollars. Morgan accepted the same day, whereupon the master of Wall Street congratulated his rival on being the richest man in the world. The Arch Competitor had sold out to the Baron of Market Rationalization and went on to give away more than 90 percent of his wealth in the form of libraries, concert halls, church organs, foundations, and pension funds—even pensions for the men who had fought him in 1892.

Carnegie’s passing from business fittingly closed a grand chapter in the American Industrial Revolution, one that in thirty-five years had turned America from a former colony and rural backwater into the world’s greatest industrial power whose manufacturing capacity made up nearly one-third of the world’s total and nearly surpassed that of Britain, France, and Germany combined. Perhaps it is as good a time as any to look back—the previous thirty-five years had been a whirlwind.

In 1867, the United States produced 22,000 tons of steel. Six years later, in 1873, it produced ten times that amount, or about one-third of Britain’s production. Seven years later, in 1880, the United States produced 1.3 million tons, equal to Britain’s effort. Ten years later the United States produced almost 5 million tons, or almost equal to Britain’s (3.6 million) and Germany’s (2.2 million) efforts combined. Ten years later, in 1900, the United States produced 11.4 million tons to 4.9 for Britain and 8 for Germany—together these three countries produced 88 percent of the world’s steel. In 1860, a typical American blast furnace produced forty tons a day, in 1900, five hundred tons. In 1867, Bessemer steel cost $166 a ton, in 1900, $19 a ton—less than a penny a pound.

One of the river mills that sprang up in the Gilded Age was a plant along the Susquehanna River, downstream from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Calling the place Steelton, some railroad investors began an ironworks there in 1867 to make rails using the Bessemer process. The railroad men were adamant: iron rails were both dangerous—they could split—and short-lived. The men needed Bessemer rails. So the Steelton plant of the Pennsylvania Steel Company began churning out steel rails by the ton, and vastly improved railroad reliability and efficiency.

Accordingly, the Steelton mill was profitable, but by 1882, its manager worried that the present steel industry, by growing inland and westward, was too vulnerable to railroad corporations for delivery of materials. He sent his best engineer—a man named Frederick Wood, who turned out to be something of a steel industry genius—to Cuba to assess iron ore there. Wood found the ore near Santiago to be good, so Pennsylvania Steel in Steelton persuaded the Bethlehem Iron Company in Bethlehem to partner with it for bringing Cuban ore up the East Coast, there to be made into steel “in deep water.” For the site of a new Atlantic Coast mill, Wood recommended a spit of land called Sparrows Point—named for seventeenth-century landowner Thomas Sparrow—several miles downstream from Baltimore where the Patapsco River flows into Chesapeake Bay. Cuban ore would arrive by ship and Pennsylvania coal by rail. Wood began laying out his mill.

By 1891, the mill, locally known as the Maryland Steel Company, was being run by the thirty-four-year-old Frederick Wood. The steel company also built a company town on Sparrows Point to house, provision, and educate 2,500 workers and their families. The town included its own police force, which watched over sobriety and morality, and enjoyed practical autonomy from the state of Maryland. Happy to be presented with unencumbered land, Wood designed a plant for maximum efficiency and maximum scale. Short rail lines connected two blast furnaces to two Bessemer converters that were twice as large as Carnegie’s and continued on to the finishing and rolling mills, where Wood installed the latest in high-speed shaping equipment. All was to be logical and orderly. Wood also invented a means of pouring Bessemer steel out of a ladle into ingot molds positioned on railroad-car platforms for railroading to the next step in the process—ingots had been formerly pushed by sweating men. Using railroad flatcars hastened the transportation process, made it safer, relieved the workers, and prevented much wasted steel that cooled too quickly. This method lasted nearly a century.

As a young engineer, Frederick Wood designed many of the buildings and machines at Sparrows Point that developed the modern steel industry.

Ever inventive, Wood fashioned machines for removing steel from the ingot molds and improved the method and speed of rolling and squeezing the ingots into the shape of steel rails, rods, bars, or plates. He applied tremendous engines to his Sparrows Point works, one of 2,500 horsepower. Wood was also nimble at snatching ideas. In Europe, he was impressed by the long train sheds that covered tracks behind railroad stations. These were steel-framed, multistory, high and long, and lined at the top with clerestory windows for expelling heat, soot, and smoke. He brought the design to American steel sheds and rolling mills, thus eliminating the stacked-floor factory architecture of old mills. Wood’s mills became long and airy, and they more readily expelled heat and foul air at the top. The design also better accommodated both the moving cranes overhead that lifted ladles and the rail tracks below that transported materials and ingots. Sparrows Point mills began to look like railway sheds, and other steelworks took up the style. In the twenty years from 1875 to 1895, Wood cut the cost of making steel rails from $60.20 to $23.12 a ton. The Bessemer work in Steelton in 1875 produced eighty tons a day; the Bessemer work at Sparrows Point in 1895 produced three hundred tons a day.

As welcome as many of Wood’s innovations were, the work was still demanding, to say the least. The coking ovens and blast furnaces were too costly to turn off and stoke up again, so they were run continuously in two shifts. Accordingly, in the 1890s men worked eleven-hour day shifts, thirteen-hour night shifts, and twenty-four hours straight from Sunday into Monday when the shifts changed. This allowed one day off every two weeks. Workers had no vacations and only two holidays a year—Christmas and the Fourth of July, both unpaid. Work habits and efficiency drives were relentless. But steel flowed from the American mills with increasing abundance. The classic cornucopia of fruits, grains, and vegetables was looking, for America, more like one spewing rails, beams, trusses, and steel plates.

THE REASONS for the country’s industrial corporate triumph are many and varied. Certainly, abundant, unprecedented resources played their part. The philosophy of social Darwinism aided and abetted. So did laws and courts that held a man’s factory practically as sacrosanct a piece of personal property as his home or his pocket watch. So did immigration, which provided strikebreakers and workers willing to sweat for almost any wage. American workers labored longer hours than their counterparts in Europe. Additionally, in America there was also a kind of spirit, a drive that was meant to match the breadth of the continent. Freewheeling, gutsy, starry-eyed former farm boys and urban urchins concocted visions and promoted schemes so large that men of smaller enclaves like England, France, and Germany blanched when hearing them. American tinkerers saw the scarcity of laboring men as an opportunity to dream up generations of labor-saving machines. And while Old World capitalists were loath to dispose of serviceable machinery, Americans burned with frontier zeal to leave yesterday’s methods in the dust on a dash for the new and improved.

This leap of industrial prowess came at a tremendous price. Natural resources were used up, even wasted, at alarming rates. Pollution—not only in the form of fouled rivers and lakes but also in that of the devastation of forest, farmland, and beautiful waterfront sites—ran practically unchecked. Even worse, broken bodies and demented spirits lay everywhere. The men who stitched together US Steel may have concluded, consciously or not, that the costs of unrestricted competition among companies making such huge investments of men, land, and capital were too great and that only planning and cooperation could stem the appalling waste.

The United States Steel Corporation brought under one financial umbrella Morgan and Gary’s Federal Steel combination, several other Chicago-based combinations, a finished-product conglomeration that Morgan had also put together, the Carnegie plants, and the Rockefeller ore properties. It comprised two-thirds of American steelmaking capacity. In 1906 it would build a tremendous mill southeast of Chicago on Lake Michigan sand dunes that it would name the Gary Works, after Elbert Gary, and help found the town adjacent—Gary, Indiana. US Steel’s original capitalization was $1.4 billion ($40 billion in 2015 dollars), making it the largest corporation in the world at the time. It represented one twenty-fifth of America’s national wealth, or more than the value of all the wheat, barley, cheese, gold, silver, and coal produced in the country in 1900.

A child and young woman emerge from steelworker housing near Pittsburgh in a photograph taken about 1909 by Lewis Hine.

Little materially changed when US Steel was formed—the production revolution continued at full throttle so that steel output increased another 250 percent by 1910—but the very structure of the holding company had its effects. No longer owned by a privately held small partnership, as the Carnegie Steel Company had been, US Steel ownership was now divided among thousands of stockholders, answerable to the investment bankers who birthed it. Almost immediately, the new corporation became a conservative force financially and technologically. Profits and dividends became more important than cost-cutting; less money was put into new, more efficient machinery.

A second effect was bolstering the struggling Progressive Movement. Although by no means the worst, US Steel was the largest of the ethically questionable business trusts and drew the ire of a public fed up with stock watering and monopolies. In 1900, 1 percent of the nation’s population owned 50 percent of its wealth, and moneymen were reaping millions merely by midwiving mergers. Businessmen, once seen by the public as “agents of progress,” devolved in the minds of many to “malefactors of great wealth.” Even churches substituted sermons on the striving of the individual for those on social responsibility. Teddy Roosevelt, skillfully galloping with this stampede of reform, proposed his Square Deal and prodded government and courts as never before into the arena of industrial production.

IN EUROPE, equally fundamental changes were emerging in the years around the turn of the century, one technological and one geopolitical. First, European science so increased the knowledge of chemical elements and the nature of metallic bonds that steelmakers there could begin to improve steel with such additives as tungsten, manganese, nickel, and chromium. These elements, mixed mainly in steel that was used for tools, helped fabricate drills, saws, and lathes that, with increasing rapidity and low cost, could shape the metal the mills were making. This meant better and cheaper electrical turbines, oil-rig pipe, ball bearings, axles, internal combustion engines, container cans, chemical storage tanks, pipelines, ship armor, and explosive shells.

The other change was a function of the notion of growth. Europe and America for decades had absorbed—generally in the form of rails—all the steel the producers could make. But by the 1890s, it had become obvious that Europe was both bloated with capital and about to see the end of its railroad-building era. The obvious solution was to invest the capital overseas and create a demand in less-developed countries for railroads and manufactured goods. There were additional benefits as well: the less-developed countries could ship cheap food to the industrialized ones, and the industrial countries could exploit such natural resources—especially the rare elements tungsten, manganese, and chromium currently coming into vogue for steel alloys—as were found in exotic places of the world. This trade spurred colonialism and the descent of the northern nations upon the non-steelmaking societies of the south and east.

Britain was an early and adept player of the game. The United States could largely remain aloof because it still had its own continent to fill and because its markets grew within its own borders as millions of immigrants settled in the new land. Germany began late, but with fervor. The Kaiser bolstered exports, and, in order to rival Britain on the sea over which most of those exports flowed, built a powerful navy with Krupp steel. The Kaiser’s push into Morocco for iron mines almost started World War I in 1911.

Unfortunately in the long run for millions of future soldiers, but not unpleasantly for certain businesses, another outlet for steel companies—whose traditional markets had been railway equipment—was armaments. The Krupp enterprise, now run by Fritz (son of Alfred) and then Gustav (son-in-law of Fritz) in what had become a dynasty, especially capitalized on the spit-and-polish Zeitgeist and sold cannons to governments large and small around the world. In America, a Krupp patent for making steel plate used in ship hulls was taken up by US Steel. The royalties were expensive, but paid dividends to US foreign policy when American fleets pounded older Spanish ships in Manila Bay and outside Santiago, Cuba, in 1898. Bethlehem Steel was also heavily committed to armaments, as the US Navy had been an important customer since the 1880s. By the turn of the century, Bethlehem Steel was making long-range guns from a superior alloy of its invention, with Charles Schwab leading the charge. Schwab had had a falling out in 1903, two years into his US Steel presidency, with the strong-minded chairman Elbert Gary and left to take up the reins at Bethlehem, soon boasting he would make his new plant “the greatest armor plate and gun factory in the world.” Schwab traveled to Europe and South America hawking armor and weaponry. In 1913 he bought for Bethlehem Steel a Quincy, Massachusetts, ship and submarine builder.

Munitions became a huge business, one of national pride and vital to national economies—European companies such as Vickers in Britain, Schneider Frères in France, and Škoda in Austria-Hungary all competed fiercely with Krupp. It was a complex and morally ambiguous business. Politicians, diplomats, and generals might be in the secret employ of armament makers, who tended to sell to any country, even potential enemies—Vickers and Krupp traded patents on weaponry that would soon be turned against their own countrymen.

Hell burst its banks along the French-German frontiers in 1914. Kaiser Wilhelm II had seen his Germany grow so strong so fast that he may have felt his people invincible. If he had left well enough alone, he probably would have lived to see Germany dominate Europe peacefully, but he was vainglorious and impatient. He thought that the world’s second-greatest steel power could take on Britain (third), France (fourth) and Russia (fifth). He wanted to keep the United Sates (first) out of the war.

The Kaiser nearly succeeded. Krupp’s “Big Bertha” cannons pounded to rubble the supposedly impregnable fortresses of Belgium, winning for the Germans the considerable Belgian steel industry and opening the way to Paris. Only another product of the steel age, the taxicab, saved the French capital by running troops out to stiffen the line at the Marne.

Steel manufacturing did not start the Great War—though some argue that naval and armaments rivalries played their part—but steel certainly worsened it. The machine age, so much a product of the ability of Europeans for making steel, manufactured the first “machine war,” and the war became a horror; death rode the production line.

The Allies immediately looked to the United States, with its tremendous steelmaking capacity, for help. The British War Office secretly cabled Charles Schwab two months after the war’s outbreak, and later the same day the Bethlehem Steel president booked passage on the Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic, under a false name. Once in England, Schwab conferred with Lord Horatio Kitchener, the secretary of state for war. Kitchener asked for forty million dollars in munitions, including two hundred large guns and one million rounds of shells, on the condition that Schwab stopped selling to Britain’s enemies; Kitchener knew that Bethlehem had sold several large guns to Germany earlier in the year. Schwab agreed, then met with First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill (then thirty-nine years old) and First Sea Lord John Fisher. These two wanted submarines in a hurry. Schwab offered twenty at twice the peacetime speed of production and twice the price. Churchill and Fisher agreed to Schwab’s terms, the arrangement being that Bethlehem would ship submarine sections to Britain for assembly in British waters.

United States neutrality laws at the time allowed free sale of armaments to warring powers, but not manufacture of warships for them in US ports. President Woodrow Wilson warned Schwab, who then sailed on the Lusitania back to Britain in December 1914 and reworked the contract. Now, under a new agreement, Schwab would secretly deliver submarine parts to Montreal, Canada. The British government would lease a Vickers armaments facility there, then allow Bethlehem Steel to use it for free. Schwab would assemble the submarines at the Vickers site for the British, raising the price of each submarine above the previously quoted figure for good measure. The cover for the steelmaking surge was that Bethlehem yards were furiously fabricating steel for bridges destroyed in the fighting and that shipment to Europe was by way of Canada. Soon the Wilson administration discovered the ruse, but settled for vague language that allowed parts going to Canada to be legal. The Germans also discovered the deception. So disconcerted were they by Schwab’s energy on behalf of the British that they offered to buy him out for one hundred million dollars; Schwab, despite what might have been sympathies for Germany on account of his ancestry, refused.

Charles Schwab leaving the White House shortly after World War I. He rose to be one of the most powerful businessmen in America.

Besides producing massive armaments orders for the Allies, Schwab had other big ideas. With the wartime profits pouring in, he wanted to expand Bethlehem Steel out of its Lehigh Valley works. Pennsylvania Steel, owner of the Steelton works south of Harrisburg as well as Maryland Steel at Sparrows Point, was a company in trouble. It had done well before the war selling rails to railroad projects around the world—Australia had been a large client—but when the war broke out, nations suddenly had other priorities and orders for rails dwindled. Bethlehem’s stock value was up and Pennsylvania’s down. In late 1915, Schwab bid for Pennsylvania Steel and got it, taking Sparrows Point in the bargain, an Atlantic coast facility prized for relative ease of shipment to clients in Europe. Schwab’s purchase doubled Bethlehem Steel and created a company now larger than rivals Jones and Laughlin in Pittsburgh, Lackawanna in Buffalo, and Midvale-Cambria in Johnstown. Schwab told Baltimore’s mayor and assembled potentates in late 1916 that he would turn Sparrows Point into the largest steel mill in the world.

By then he had already made Bethlehem Steel the world’s largest munitions manufacturer. Plants in Bethlehem and at Sparrows Point churned out shells, armor plate, artillery, and naval guns. It was making three thousand shells a day before the war, but eight times that number by the time of Schwab’s speech in Baltimore. Its specialties were armor-piercing shells and shells that burst above the ground, the better to spread their lethal shrapnel.

By the time the United States entered the war in early 1917, its industry was in full wartime stride. In one year it riveted together more than three million tons of shipping to handle supplies and made the Allied armies the best-equipped and most powerful forces in the field. Adding the United States to the Allied efforts crushed the Kaiser’s hopes. In 1914, the United States produced 23.5 million tons of steel, in 1918 almost twice that at 44.5 million tons. Bethlehem Steel’s profit margin in 1917 before taxes was 29 percent.

The worst war yet known was bound to have tremendous consequences, and it did—not the least of which began in Russian steel mills. There, peasants newly trucked in from the farms formed a proletariat unlike any known in Russia or the world. Like the industrial workers of early nineteenth-century Europe, the Russian workers suffered minimal living standards, but unlike their earlier counterparts, they did not have time to assimilate to an unfamiliar industrial culture before their society came under the pressure of total war. As institutions around them began to strain, Marxist arguments flourished, and the steelworking proletariat helped lead the revolution that established the first communist state.

The example of the Russian workers stimulated wage earners throughout Europe and America; strikes and uprisings marked the years 1919 to 1921, and the owners of capital, horrified at the Bolshevik example, dug in their heels. During the war, labor had gained ground when governments temporarily forced collective bargaining on the management of war-related industries in order to assure strike-free production. The United States started the National War Labor Board, in large measure to preserve labor peace so factories could keep rolling out munitions. It favored an eight-hour day and the right to collective bargaining through a union. After the war, the National War Labor Board was dissolved, and management hoped to return to prewar practices. But labor’s ranks had swollen during the war production frenzy. Unions knew they had gained new power and they struck to hold their gains.

After President Wilson had implored both sides to moderation, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) called for the largest strike in the nation’s history, involving 350,000 workers. Most of them were foreign-born, and pamphlets on both labor and capital sides were printed in as many as twenty-three languages. Labor claimed their goals were collective bargaining and a shorter work week. Management countered that the workers were misled by outside organizers, many of whom, in management’s opinion, were Bolsheviks or Bolshevik sympathizers and were really working to establish, first, a “closed shop,”—that is, an all-union force at any particular mill—and then domination of the plants by dictating what the workers could and could not do. Managers saw the struggle as one over control of their industry. Passions ran high on both sides, and tactics were low. Each side accused the other of using force to intimidate workers, and union people complained the companies not only used spies to ferret out organizers but also supported local authorities who deliberately interfered with the free right of assembly and speech.

Ultimately, the strike of 1919 failed in the United States. American opinion ran strongly against foreigners, especially Eastern Europeans, who by now made up the majority of the unskilled workers in the mills. Fear of Bolshevism was strong. Among the public, perception of the nation’s workers morphed from heroic “patriots” in 1917 and 1918 to suspicious “Reds” in 1919. The great strike had some immediate results. It pulled the federal government further into the affairs of industrial production, the government ostensibly being the agent of the public now that the steel industry was so vital to the health of the country. And the strike also drew forty thousand Southern blacks to Northern cities as strikebreakers. Accordingly the failed strike aggravated the distrust between white and black steelworkers, but also between the American-born and the foreign-born. Worker solidarity, important to union organizing, was seriously strained. In Europe similar strikes failed, but the workers were quicker to identify themselves with a class, to embrace political doctrine, and to force political concessions. In Britain, for example, the efforts of the workers led to the creation of the Labour Party.

Even apart from the labor question, the steel industry was going through spasms, especially in Europe. The postwar Treaty of Versailles snatched iron-rich Alsace and Lorraine from Germany and restored them to France. It also granted France the coal-rich German Saar region for seventeen years, and it demanded huge war reparations, some in the form of German Ruhr coal. All this helped France, which had lost a quarter of its foreign investments when the Bolsheviks seized French-owned steel mills in Russia. The French also dictated that half of Krupp’s works be dismantled. Consequently, Germany pleaded impoverishment in 1922 and refused to ship more coal to French coke ovens that stocked French blast furnaces. In response, French troops invaded the Ruhr in 1923 and for almost three years controlled 80 percent of German steel production, demanding payment in coal or cash. Germany responded with passive resistance and paying what it could in inflated marks that were quickly becoming worthless. The French occupation grievously strained the German economy, and the simultaneous hyperinflation ravaged the savings of the middle class, which then focused its hatred on the Allies as well as on those Germans who had acquiesced to the Allied demands. The German steelmakers were actually not so hard hit; they could repay old loans in inflated marks and take out new loans, many from the United States, to rebuild plants with improved equipment. Fritz Krupp even secretly expanded his operations by controlling steel mills in Russia, Holland, and Sweden and began to manufacture there what was proscribed to him by treaty—airplanes and cannons.

The 1920s were generally good years for American steelmaking companies, and their prosperity was reflected in the bustling economy. Management was content that the strike of 1919 had failed and unionism blunted. US Steel won a Supreme Court decision when the justices ruled that size alone was not reason enough to call for the corporation’s dissolution; compared to the prewar Progressive era, the Harding and Coolidge administrations were friendly toward large corporations. But there was shifting and sliding among the industrial giants. US Steel was still attempting to rationalize the disparate plants it had cobbled together at the turn of the century, shutting down some of the smaller operations and attempting to jigger the remainder into an efficient operation. Though three times larger than its nearest rival, Bethlehem Steel, US Steel grew slower and had less favorable margins. Smaller companies, including Bethlehem, were prospering in its shadow. Bethlehem Steel continued to grow, raising New York skyscrapers with its new lower-cost and stronger I-beam, the silhouette of which became Bethlehem’s corporate symbol. Steelmen who worried that nothing would take the place of orders for guns and ship hulls were pleased when automobiles, surging in popularity and switching away from wooden bodies, demanded more steel, as did household appliances such as washing machines. The market for thin, tin-covered steel for food cans burgeoned. Dole (pineapples), Campbell’s (soup), and Hormel (meats) were only some of the companies demanding millions of steel cans.

From 1919 to 1925 in the United States, productivity increased 15 percent in transportation and 18 percent in agriculture but 40 percent in manufacturing, largely owing to labor-saving machinery. Wages rose. Schwab offered a bonus system—more pay for more product—and some skilled workers in his plants could make ten or twelve dollars a day. The bonus system actually worked better for the highest managers than it did for workers in the mills, though most of this was cloaked from the public. Stockholders were outraged when they learned that Bethlehem’s board secretly divided a profit pool of $39 million by paying $13.5 million in executive bonuses before dispensing the rest to stockholders. The average bonus of fourteen Bethlehem top managers in 1929 was $244,665, or 114 times the $2,150 annual wages for their mill workers. The Bethlehem elite were the highest paid in the nation.

America was flush with money, principally because Britain and France had liquidated foreign investments during the war in order to buy American steel products. So much capital flowed west across the Atlantic that New York replaced London as the world’s financial center. Some of these funds speedily returned to Europe, such as those that helped rebuild Krupp steel plants and pay German reparations. Other monies opened iron mines in Cuba, Brazil, and Venezuela.

In early 1922, Bethlehem Steel bought Lackawanna Steel near Buffalo, the fourth-largest of the companies operating in US Steel’s shadow, Bethlehem being the largest. The purchase opened the Great Lakes market to Bethlehem. Later that year Bethlehem bought the second-largest of the independents, Midvale Steel, whose major works were at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The expansion made Bethlehem one-third the size of US Steel, three times larger than its next rival, Jones and Laughlin, and larger by assets than either General Motors or Ford.

By this time Schwab was increasingly intent on smelling the roses. He surrendered more and more work to thirty-nine-year-old Eugene Grace, son of a New Jersey ship captain, graduate of Lehigh University, and zealot for profits, whom Schwab in 1916 had named Bethlehem president. Truth be told, Schwab had become less a man for the grit and sting of the mills than a man of grand gesture, of huge deals—and by the early 1920s he was intent on luxurious living, thanks to the vast wealth he had accumulated from Bethlehem’s World War I business and from his continuous stream of dividends. Schwab had already completed a mansion on Riverside Drive in New York City in order to outshine the Manhattan Astors, Vanderbilts, and Rockefellers—in fact, it was the largest mansion in the city. He had bought an entire block between 73rd and 74th Streets, then erected a chateauesque pile costing $3.5 million when it was completed in 1907 ($92 million in 2015 dollars). Inside were a gym, bowling alley, swimming pool with pillars of Tuscan marble, and dining area to accommodate 250—all in French Louis style of one sort or another—plus a fortune in paintings and sculpture. French chefs and servants were on call continuously. For one dinner Schwab paid opera tenor Enrico Caruso a fee twelve times what one of his millworkers earned in a year.

But Schwab’s On the Hudson—also called Riverside—pales in comparison to the thousand-acre summer retreat he built over the years in Loretto, Pennsylvania. This he called Immergrün, (German for evergreen). The mansion, a limestone Renaissance castle, was only a small part of the estate. Surrounding it were a 133-acre golf course, a fourteen-step water cascade between double stairs leading to the manse, world-class landscaping, and a Normandy village with stables, farmer’s cottage, barn with bell tower, and homes for sheep and pigs. Chickens lived in reproductions of French cottages; a water tower was made to look like an English fortress. Schwab’s philosophy of wealth was nowhere near Carnegie’s. Schwab was a spender. And he was also a gambler, particularly inclined to the tables at Monte Carlo.

Schwab was lavish with money in other ways. Over fifteen years in this period, he oversaw payments of $62 million ($836 million in 2015 dollars) to only about twenty-four men, two-thirds of it going to Eugene Grace. But truth be told, during the 1920s, Schwab and Grace were also pouring money into their business. From 1923 through 1928, they spent $158 million ($2.14 billion today) in cash improving their mills from Baltimore to Buffalo. The Sparrows Point plant in particular expanded rapidly. By 1929 employment there reached eighteen thousand, half again as high as its peak during the war years. Sparrows Point was making two and a half tons of steel each minute of the day, and its payroll was fueling Baltimore. But the work remained grueling. In the rolling mills, for example, much of the work required physical endurance and standing up to exhausting heat. Despite new machinery, much of the labor came from the muscle of men’s backs and hands. Steel plates were heated to cherry red and fed with tongs by a man—called a rougher—into a set of rollers, which partly pressed the steel. It was caught on the opposite side by a catcher with his tongs. A screw boy minutely diminished the distance between the rollers as the catcher passed the glowing steel back to the rougher, who then fed it in again—over and over for hours until the thinness was right. Summertime was particularly excruciating. Except in the most demanding jobs, men worked ten or more hours a day and, until the mid-1920s, the twenty-four-hour swing shift. Because of the shift changes, men worked six-day weeks and never saw more than twenty-four hours off but once every nineteen days. President Harding called on US Steel’s Chairman Gary to reduce worker hours, but Gary held firm for a year before yielding. Compared to a man with a white-collar job, an American steelworker in these years had a life expectancy seven years shorter.

Charles Schwab’s New York City mansion nestled on an entire block and was the largest in the city in the 1920s.

WHEN THE 1920S ENDED, so did a way of life. The steel industry did not create the worldwide Great Depression—nature’s work on crops and mankind’s financial schemes are better targets for blame—but it shared in the suffering, and the solutions it sought had widespread ramifications. The steel industry was at the forefront of damage; people could not stop buying shirts and food, but they could put off building skyscrapers and ships. Orders dried up. America had the capacity for making seventy-one million tons of steel, but in 1930 made only twenty-nine million tons, 41 percent of capacity. In 1932, Pittsburgh steel factories did even worse, running at only 32 percent of capacity. US Steel made twenty-five million tons of steel in 1929, earning $198 million, but a paltry six million tons in 1932, losing $71 million. The United States could make half of the world’s steel, but in 1932 made about 27 percent. Myron Taylor of US Steel (Gary had died in 1927) laid off 67,000 workers. Eugene Grace laid off 12,000, leaving only 3,500 at Sparrows Point. Grace also cut the base hourly rate of his workers from forty-five cents to thirty-four cents. To avoid further layoffs, he established a “spread the work” tactic. Men might work three five-hour days or fifteen hours a week, down from seventy hours a week in the 1920s, and receive a paycheck twice a month of ten to fifteen dollars; what savings many steelworkers had put away in the 1920s they had to consume in the 1930s. Meanwhile, Grace, who would rule Bethlehem Steel until 1957, did not lower his own base salary of $180,000, nor Schwab his of $250,000.

As well as in America, the skies over Sheffield in England, Essen in Germany, and Le Creusot in France cleared of soot, which the workers took as a sign of despair. Plant expansions that steel companies had ordered in the 1920s now worked against them. They were paying for plants and machinery that were idle; their losses went from bad to worse, quarter after quarter, year after year.

Only in the Soviet Union could the steel industry beat its chest. Central planning, ruthless discipline, and a strategy to increase heavy industry at the expense of consumer goods and agriculture—exacerbating the Ukrainian famine of 1931–1932 and swelling the ranks of the more easily politicized proletariat—managed to turn the devastated country of 1922 into the industrial giant of 1939. During the ten years of the Depression, Soviet steel production nearly quadrupled, an astonishing achievement. Soviets crowed to a world mired in unemployment and made the most of their propaganda.

In other great steel countries, people had to look at themselves squarely and ask, “Can free enterprise and capitalism exist here anymore?” Invariably, the answer was, “Not as in the past.” The methods of altering free enterprise, however, differed from country to country. In Britain and France, capitalism was saved by the intervention of government, which with good doses of central planning helped to regulate markets and production.

Germany took a not-so-different course—central planning but with one big difference: it discarded democratic institutions. The German people in general and the Krupps in particular pledged allegiance to their Nazi leader—who had seized power during the height of the Depression in 1933—and looked the other way when dissenters were crushed through compulsion or violence. The Krupp family was not sorry to see the Weimer Republic vanish; Hitler favored a rearmament program, and steelmakers began once again to make money, much of which flowed back into Hitler’s political coffers. The Germans, however, found it difficult to sell into international markets because so many countries had erected formidable tariffs. So the idea blossomed in Germany that their Reich should economically dominate much more of Europe—all that it would need was more land and more markets to make the economy hum as during the Kaiser’s days.

In the United States, strong measures were obviously needed; the factories were idle and the workers impoverished. Many owners and managers in the steel industry, as distressed as they were over low production, were willing to see the Depression run a free-market course, letting unemployment rise so high that wages would plummet. In addition, such a course would lower their labor expenses and have the added benefit of setting worker against worker, thereby diminishing unionism. Whether freedom in America could have withstood the strain of such a course is a matter of debate, but Franklin Roosevelt, having taken the presidential reins in 1933, would not tempt revolution. Instead he “betrayed his class”—the capitalist class—and put government to work where American government had never gone except in the emergency of World War I. Under the National Recovery Administration (NRA), Roosevelt instigated a kind of central planning and collaboration in large industries, including the steel industry. Once set up for steelmakers in late 1933, the planning and collaboration helped. After years of losses, price stabilization instigated by the NRA, plus new orders stimulated by federal government programs for railroad work, increased revenue—Bethlehem Steel made money in the last quarter of 1932.

Steel companies could catch one ray of sunshine in the Depression: they shooed beer out of glass and put it in cans. Spurred by advances in rolling thin sheets to uniform and high quality, they sold their steel to two giant canning companies, American Can and Consolidated Can. After years of research and development, American Can produced a steel can that could both stand up to beer pasteurization and counteract beer’s tendency to become cloudy in steel. Steel cans did not have to be returned to bottlers as glass bottles did, and the price for delivering beer to stores dropped. Pabst was the first of the national brands to give up glass and turned to silver-and-white steel cans. Schlitz came out with a brown-and-yellow can. Retailers and beer drinkers took to them, and steel companies relished a new and profitable market.

Moreover, Roosevelt’s energetic secretary of labor, Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet, took up the cause of labor. As one of her first acts, she telephoned both Eugene Grace and Myron Taylor and invited herself to both Sparrows Point and US Steel’s Homestead works for inspection tours. Perkins also wanted to meet with workers privately, outside the mills. In Homestead, borough authorities considered the workers “Reds” and denied Perkins any meeting place either indoors or outdoors within the borough limits. “Where is the nearest post office?” Perkins asked and met workers there.

Hardly anything could be called normal anymore. Perkins called for a meeting in Washington of major industry leaders to discuss proposed NRA collaboration codes. Grace and other big steelmen were seated when they saw a representative of the AFL walk in; they rose as a unit and walked out, telling Perkins that if they sat in the same room with the man, the perception would be that they were “dealing with organized labor.” Perkins wondered aloud if she had “entertained eleven-year-old boys at their first party.”