CHAPTER 6

TURTLES, EYES, AND COMPASS STONES

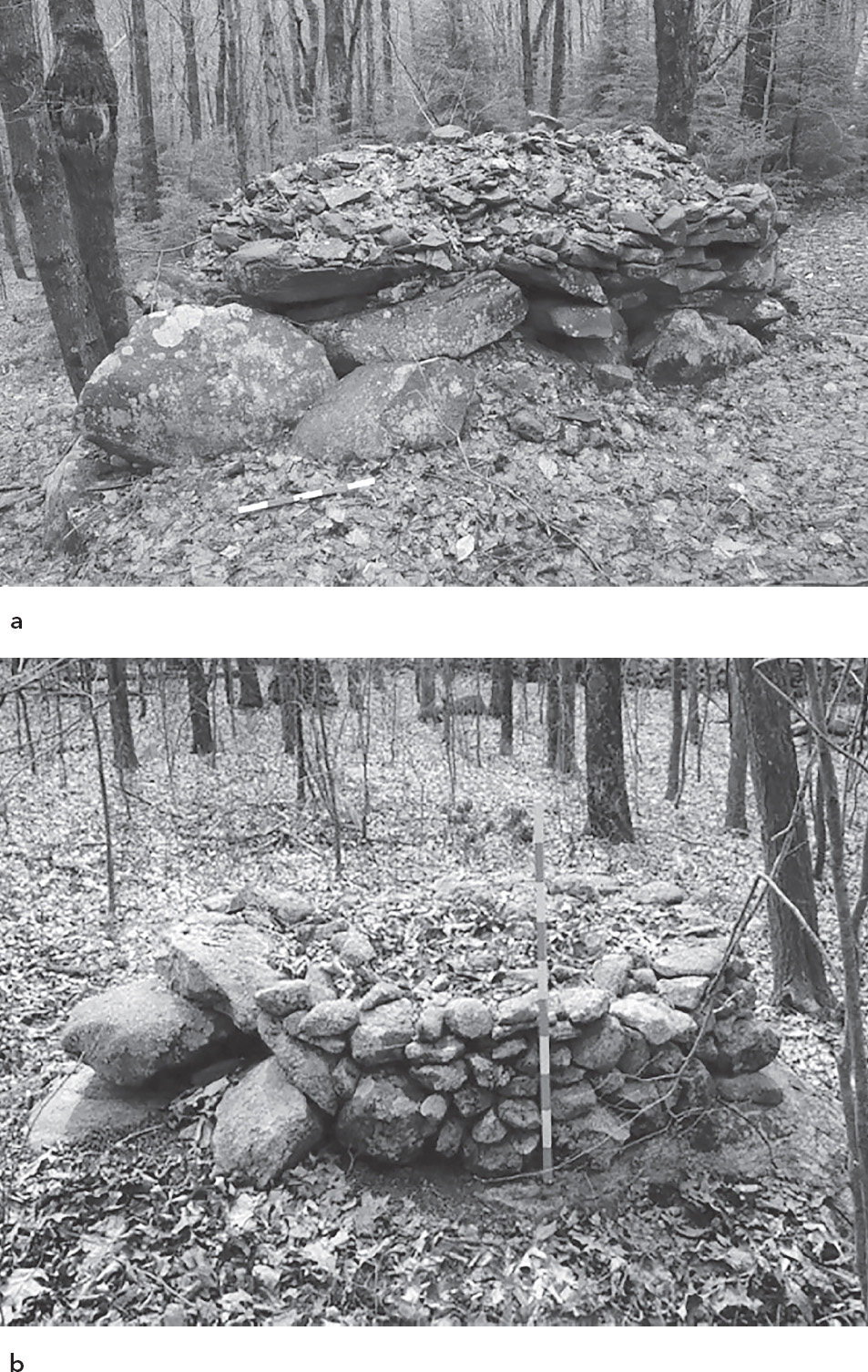

Turtles, turtles, everywhere. Given their place in Native American creation myth and culture, it should not be surprising to us to find these effigies present at suspected ceremonial sites throughout the Northeast and elsewhere. It doesn’t take much imagination to see turtle forms in many such “piles of stones.”

A universal Native American creation myth states that after a great world flood, earth retrieved from the ocean floor was placed on the back of a turtle’s shell, and that foundation was built on until it created the land mass we today call North America. Could these constructions have been created to pay homage to that myth and belief?

Another significant turtle effigy site, documented on Marlboro Mountain near Danskammer Point in Plattekill, New York, is discussed in chapter 15.

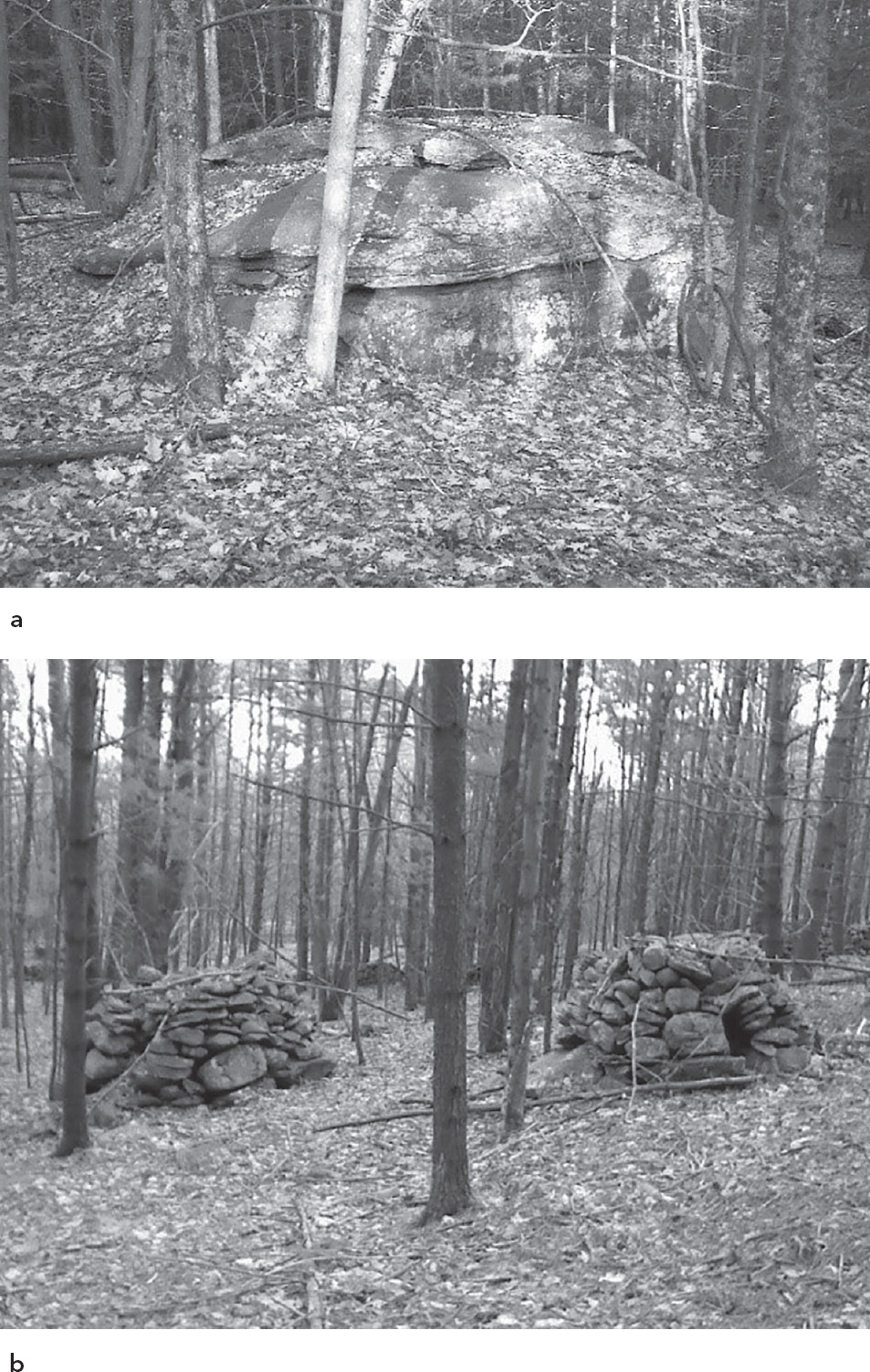

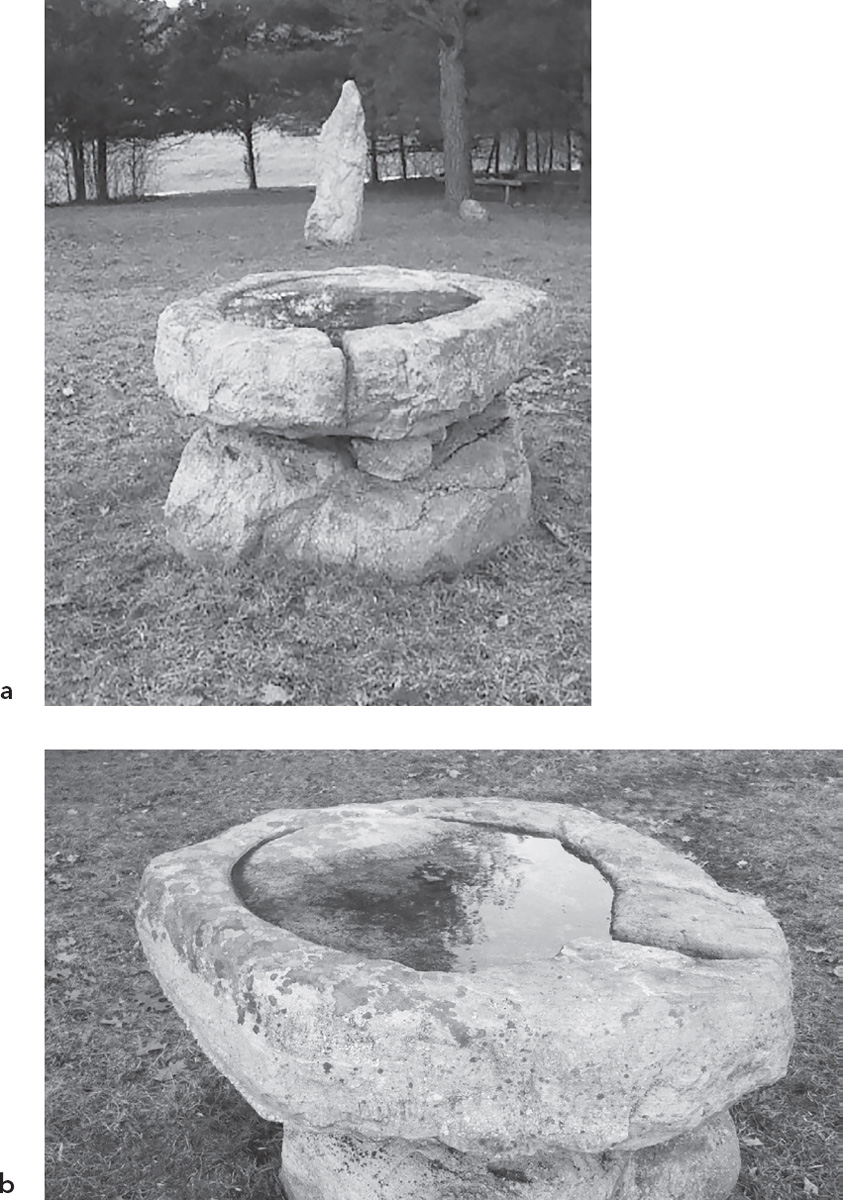

THE “EYES” HAVE IT

I was contacted by a friend who said that a friend of his was renting a summer home in Accord, New York, with an unusual stone in its yard (see figure 6.3 below). I immediately recognized it as very similar to one reported several years ago at Stone Mountain Farm in Tillson, New York, known as the Stone Mountain “sacrifice” stone (see figure 6.4 below). Both are carved out of the same white Shawangunk quartzite conglomerate, both are of similar size, both have a carved gutter, and both have the same general shape and apparent “eye” aspect to their form.

Fig. 6.1. Turtle cairn in Spruceton Valley, West Kill, New York (a); turtle cairn in Killingworth, Connecticut (b) (photo: Norman Muller)

Fig. 6.2. Turtle effigy boulder (a); accompanying turtle cairns at the Bearsville Hollow site in Woodstock, New York (b)

They were also both found in the same general neighborhood, at the foot of the Shawangunk escarpment, just on opposite sides of the ridge and a dozen miles north and south of one another.

We were at that time (early August 2014) experiencing a bumper crop year of blueberries and huckleberries in upstate New York, and the towns at the base of the mountains affectionately known as the “Gunks,” which are abundant in berries, were holding their berry festivals, which must date back to the earliest times for people of the region. One can’t help wonder if what we were looking at were early juice presses, where bunches of berries were placed in the center “altar” area and squashed by hand or implement until the juices filled the gutter and ran out the spigot, where the gutter drains, producing and providing the nectar of the gods.

Fig. 6.3. Accord, New York, “sacrifice” stone and possible original pedestal stones beneath (a); note gutter feature carved in perimeter of stone (b)

In O. G. S. Crawford’s The Eye Goddess, it is argued that an early, worldwide matriarchal culture used “eye” iconography as a foundation for the representation of a woman’s spirituality (Crawford 1958). Could these mysterious carved stones in our region be vestiges of that ancient culture and evidence that it made its way to our shores?

Fig. 6.4. Stone Mountain sacrifice stone found in Tillson, New York, with standing stone, part of a modern stone circle, in background (a); the eye stone, found one hundred yards away, was relocated and set up on the present pedestal (b)

COMPASS STONES OF THE CATSKILLS AND SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS

The enigmatic boulders known as compass stones have been identified in locations throughout the Catskill Mountains, Hudson River valley, and Shawangunk Mountains of New York. They all possess aspects and features (noses or faces) that are oriented to the four cardinal directions. In most cases, these are boulders, the size of which would not preclude the ability to have been manipulated and moved by humans.

Though there’s no record of Native Americans having developed any type of compass, elsewhere in this book I describe the possibility of Native cultures having the ability to survey point-to-point straight lines accurately through the woods with the use of line-of-sighting instruments.

The ability to distinguish the four directions would also have been of paramount importance to Native American cultures, and some of the earliest references from European settlers were descriptions of ceremonies, such as the tobacco ceremony, which involved scattering a small amount of tobacco in all four directions while honoring the great ancestor spirits in association with the four seasons. So the need to understand and accurately identify the four cardinal directions had a practical purpose besides the spiritual aspect associated with compass stone sites.

Below are examples of compass stones I’ve come across and documented over the past decade. Many more, I’m sure, exist unnoticed for their true purpose. You’ll see a few of these stones sites again, later in this book, as they also play a role in long-distance, line-of-sight, and non-line-of-sight alignments that are covered in chapter 8.

THE ONTEORA LAKE COMPASS STONE

The Onteora Lake Compass Stone, located north of Onteora Lake, in Ulster County, New York, is situated on a prominent hilltop with a view to the horizon to the north. A feature of the stone that is hard to miss is the prominent nose that points due north.

Though it is possible this large (approximately five ton) boulder, a possible glacial erratic of local Catskill sedimentary/conglomerate rock, melted out of the glacier and settled on its base stones, it seems more likely this stone was set up by humans to mark north on the landscape. The stones that compose the base appear to be purposefully placed to keep the boulder upright and oriented the way it is.

Fig. 6.5. Onteora Lake Compass Stone, north nose

Fig. 6.6. Onteora Lake Compass Stone base “chock” stone

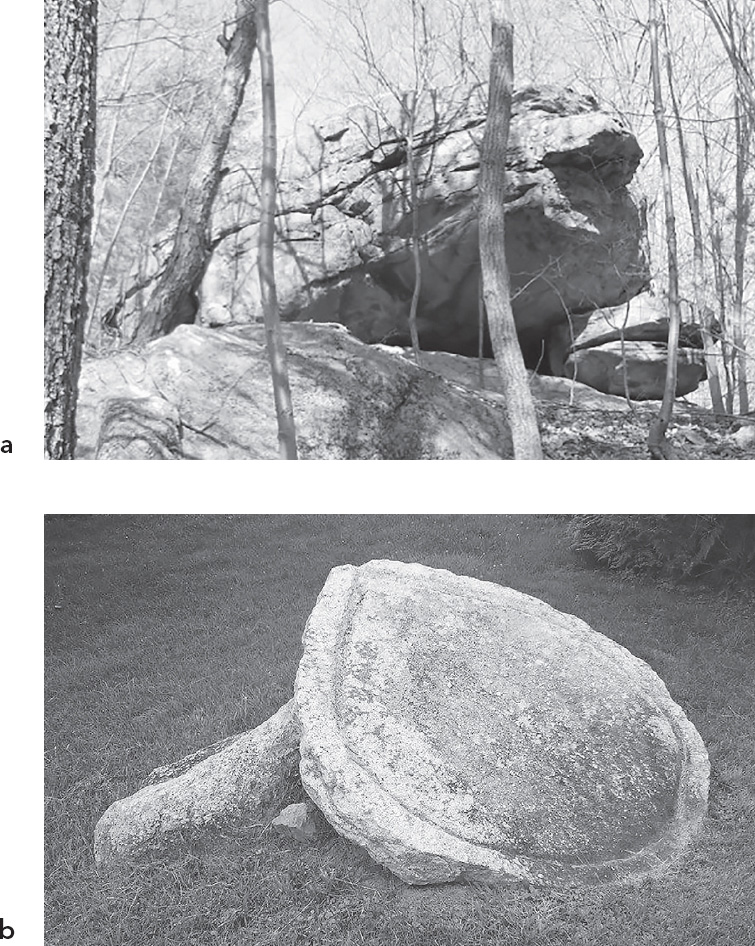

THE NORTH SHAWANGUNK DOLMEN

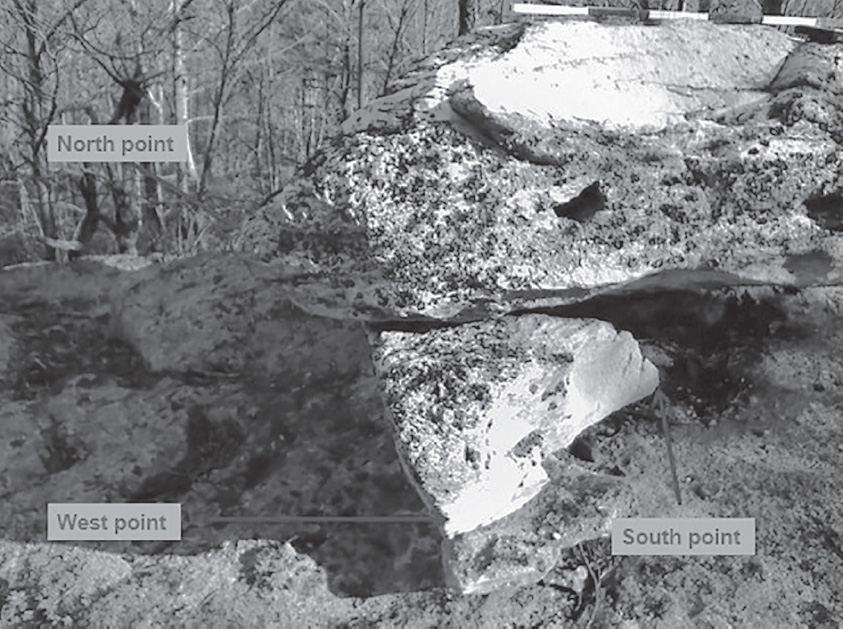

Located on a high, narrow ridgetop on the Mohonk Preserve in the Shawangunk Mountains, this site location has clear views to the eastern and western horizons. It weighs approximately fifteen to twenty tons and is set on base stones that give it an unusual angle. Located about a mile south of Bonticou Crag, this stone was brought to my attention by my friend Ian Jacobus, who, after I mentioned another stone I had encountered that had aspects and features that aligned with the cardinal directions (Reconnoiter Rock), said he knew of a similar stone, and we both wondered if it too had such an orientation. When Ian led me to this large quartzite/conglomerate boulder in the north Shawangunks, we were surprised to discover it too was a compass stone. Later, I would discover on the map the hidden relationship this stone shared with Reconnoiter Rock and its site location on Peekamoose Mountain, more than eighteen miles to the northwest.

The North Shawangunk Dolmen has four obvious “noses” that protrude from the main mass of the boulder, pointing east, south, north, and west. The east-west axis of the stone is nearly perfectly bisected by the north-south axis (see more on this stone in chapter 8, here).

Fig. 6.7. North Shawangunk Dolmen

Fig. 6.8. North Shawangunk Dolmen south point

Fig. 6.9. North Shawangunk Dolmen north point

Once, when I gave a presentation to a chapter of the New York State Archaeological Association and I showed a picture of the North Shawangunk Dolmen, one of the attendees spoke up and said he did not believe humans could move a boulder of that size (approximately twenty tons). I countered that I begged to differ with that belief and that humans around the globe had been moving boulders that were much larger for thousands of years, and that it is not disputed. I mentioned that I believed the local ancient inhabitants of the region, the Lenape, could have easily moved such a stone, if it was important to do so, it suited their purpose, and they had the desire.

PEEKAMOOSE STONE/RECONNOITER ROCK

This large boulder, known as both Peekamoose Stone and Reconnoiter Rock, is found on a high shoulder leading to the summit of Peekamoose Mountain, deep in the heart of the Catskills. It is composed of typical Catskill Mountain sedimentary sandstone/conglomerate and weighs approximately ten to fifteen tons. It rests on a single point of contact with the bedrock of perhaps sixteen inches.

Fig. 6.10. Peekamoose Stone, also known as Reconnoiter Rock

I believe twenty strong men could get their hands on this rock and spin it, if so needed, as the small base contact area would make a good pivot point.

I believe the rock may have been reoriented from its original position to have its prominent “nose” point north. Using the sun/shade line to align a compass when the sun is directly overhead, we see that north is recorded in the position of the stone. We’ll see in chapter 8 how this stone relates and aligns with the previously documented North Shawangunk Dolmen.

THE PETERSKILL COMPASS STONE

This smaller stone of Shawangunk quartzite conglomerate, weighing perhaps two to four tons, is also found on a high ridgetop, one with clear easterly and westerly views. It appears to have been set up to record the cardinal directions in stone, acting as a compass stone for those who knew to look. It is also located on the Mohonk Preserve, several miles south of the North Shawangunk Dolmen.

Fig. 6.11. Peterskill Compass Stone

Base stones have been placed to raise and orient the main stone as well as to incorporate points that orient to the cardinal directions.

Is this more evidence that a practice of exploiting natural features on the land (large stones and boulders) and marking the landscape by identifying boulders that could orient to the four directions was once common among those who traveled these lands by foot long ago? The Peterskill Compass Stone is located within sight of a main trail that travels through a pass in the Shawangunk escarpment, allowing east-west passage. This may be part of the original old Shawangunk Trail, shown on some colonial maps, which led from the Catskill Mountains to the Shawangunks.

Fig. 6.12. Peterskill Compass Stone’s three points

Fig. 6.13. Peterskill Compass Stone north point

LAKE MINNEWASKA COMPASS STONE

Above the south shore of Lake Minnewaska in Minnewaska State Park, in the Shawangunk Mountains of New York south of the Mohonk Preserve, sits a large boulder along a carriageway. This site location is also on a high ridgetop that affords good views in multiple directions. Some tree clearing would open the views up substantially, as is the case with most of these high ridgetop site locations. It is known that Native populations conducted major tree clearing activities for multiple purposes, including land and view-shed management, as well as agriculture. The Lake Minnewaska Compass Stone has unusual angles, and in addition to its east and north points, it has other prominent points that do not indicate compass directions. Due to the additional points it may not be considered a true compass stone, but the cardinal angles look very intentional to me.

Fig. 6.14. Lake Minnewaska Compass Stone