CHAPTER 13

MISSION MALTA

Exploring Sound and Energ y Properties of Ancient Architecture

The mythology of the ancient Greeks spoke of times thousands of years earlier when mythical beings with great powers were part of the cultural landscape. In ancient Greek lore the islands within and lands around the Mediterranean Sea were populated with centaurs, the Cyclops, the three Gorgons, the Minotaur, the Hydra, the Sirens, and many more nasty creatures. The origins of these hostile inhabitants make up the meat of the ancient Greek mythologies, along with the messages and lessons they hold. They most definitely came from a deeply remote time in the distant past, a time long prior to the technical and scientific terminology first developed by the Greek Civilization, though many of the creatures’ names and powers appear to have a somewhat technical root.

Prior to the ancient Greeks and the advent of scientific language and technical terminology, humans described things differently. The forces of man and nature were closely observed and described for many thousands of years by humans, even documented in the written history of many ancient cultures predating the Greeks. However, many of these texts were lost, and the surviving ones may require deciphering within a new context. A hypothetical passage such as, “the water God that resided beneath the mountain, providing pure waters and sustaining life,” could be an allegory for “hydrostatic pressure.” We can reasonably assume that before the Greeks came up with a term for the science of hydrology or the concept of static versus dynamic pressure, these concepts were still known, observed, and understood yet were described symbolically or metaphorically rather than technically.

Some believe the Iliad and Odyssey should be interpreted as coded scientific and astronomical textbooks and have devoted time to unraveling them. One example, the whole one-eyed Cyclops in the cave escape story, tells you how to make fire by spinning a stick in the punched-out “eye” hole of a piece of wood. When this was demonstrated, the wood screeched like the screaming Cyclops with its eye punched out.

Some of the most well-known Greek mythological creatures were the Sirens, women with “songs” so powerful they could apparently be used as weapons against their enemies (men). This seems to indicate the use of sound in a practical way and raises the question: What else could the ancients do with sound and energy?

While in Greek times the Sirens were depicted as svelte beauties, this image was based on the image of beauty to the contemporary Greek eye. In reality, they may have more resembled the goddesses of the temple culture on the island of Malta, where very large, zaftig women composed the ruling class. These women probably physically resembled what we might stereotypically expect to see today in a modern opera star, a large woman with a powerful, well-controlled voice. Numerous statues and figurines, part of the archaeological record of Malta dating to prehistoric times, depict just such women.

On Malta during the temple period—which dates back to 3600 BCE (long before the Greeks)—perhaps sound was being used by that culture in specific ways for specific purposes, and one cannot help but wonder if the ancient Greek accounts of sirens comes from there.

From the archaeological record of the preliterate time, it appears the Maltese temple culture, dating back more than six thousand years, apparently had no concept of war. Of the very many well-preserved examples of architecture, artworks, and inscriptions found there, none appear to depict any weapons, shields, warriors, armies, or any other image of conflict or invasion. It was seemingly a matriarchal goddess culture whose people existed for thousands of years peacefully as farmers and traders, and recent finds support the idea of it being a sanctuary of sorts. Their power and command over sound may have been their defense, which once known would have left any hostiles thinking twice. As mentioned, this could be the root of the ancient Greek mythology involving the Sirens.

There are endless variations of “wave” inscriptions found everywhere on the ancient temple constructions, though there is no record of writing, and I cannot help but wonder how the preliterate aspect of their society played profoundly into the nature of their existence and concept of sound.

How and for what purpose did the Maltese temple culture use sound energy? This the focus of Archaeoacoustics: The Archaeology of Sound, a first-of-its-kind conference, held in Malta in 2014, which took a multidisciplinary look at early sonic and aural awareness and lithic sound behavior, toward a better understanding of human and music development. We’ll talk about this conference later in the chapter.

Fig. 13.1. Large goddess figures found on Malta

Meanwhile, let us consider that understanding the soundscape that ancient humans created in the Maltese temples could enable us to finally grasp their intended purpose, for if a picture paints a thousand words, a soundscape can paint a thousand pictures. And through sound we may see what words or pictures may never show us. Perhaps a combination of tones created by humans in a variety of ways can produce an “anthrophony” of sound, which could act as a key to unlock a temple’s function.

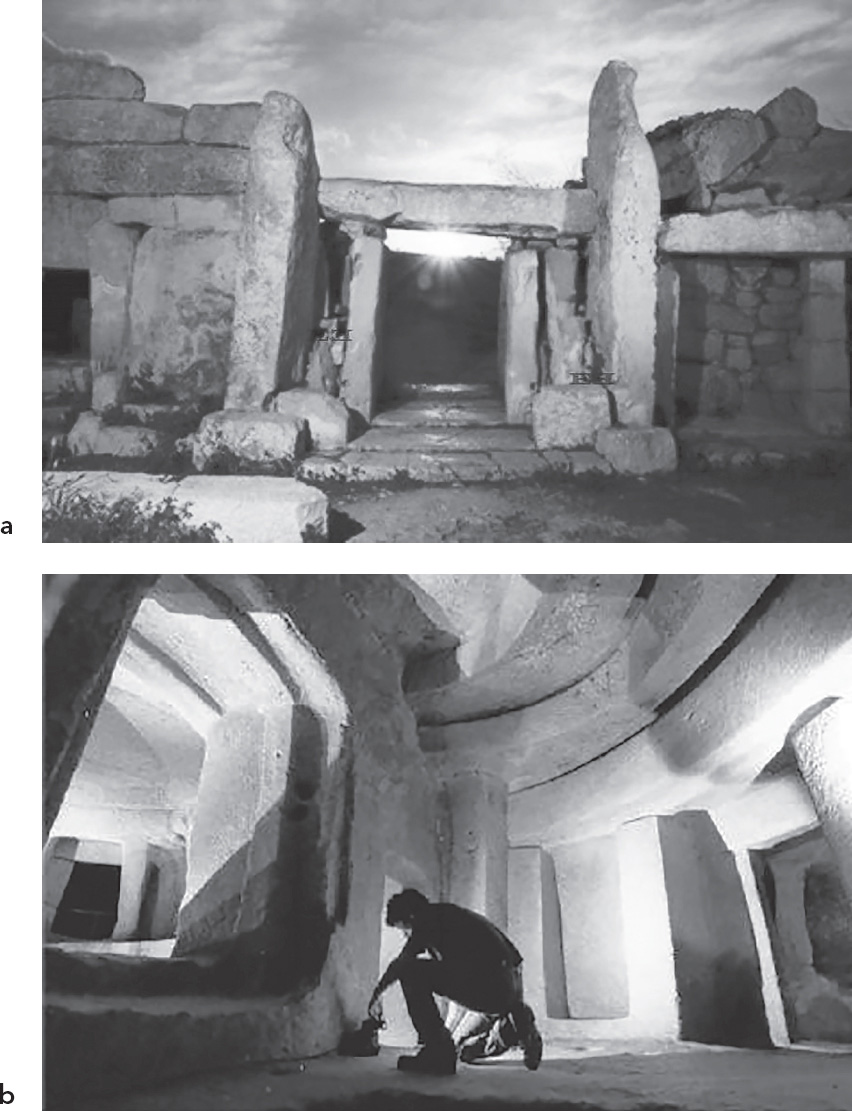

Fig. 13.2. Megalithic construction, Hagar Qim Temple, Malta

Fig. 13.3. Wave-form inscriptions found in a Tarxien Temple, Malta

UNDERSTANDING FORMANTS

Formants are defined by electrical engineer and speech researcher Gunnar Fant as “the spectral peaks of the sound spectrum of the voice.” In the science of speech and phonetics, formant is also used to mean an acoustic resonance of the human vocal tract. It is often measured as an amplitude peak in the frequency spectrum of the sound, using a spectrogram or a spectrum analyzer. However, in vowels spoken with a high fundamental frequency, as in a female’s or child’s voice, the frequency of the resonance may lie between the widely spread harmonics, and hence no peak is visible.

In acoustics, formant refers to a peak in the sound envelope or to a resonance in sound sources, notably musical instruments, as well as that of sound chambers. Any room can be said to have a formant unique to that particular room due to the way sound may bounce differently across its walls and objects. Room formants of this nature reinforce themselves by emphasizing specific frequencies and absorbing others, something that is exploited in construction techniques.

How was sound used in ancient Malta? As today, sound was used in every way possible and perhaps more. As with most sophisticated ancient cultures, they most likely had a three-dimensional worldview and used sound to express it outwardly, inwardly, and in a centered way, projecting it in all directions and on the plane of the living, for the purpose of communication, as weaponry (if necessary), and spiritually or to create altered states of consciousness. New investigations are looking at all these possibilities.

Above: Projecting Outward and Upward

- Communication with the gods

Living plane: on the ground

- Long-distance communication over the water (sound amplified over water)

- Sound as a weapon—tradition of the Sirens

Below: Underworld Belowground, Projected Inward

- Sound for altering consciousness

- Communicating with other realms, connecting with the spirit world

SOUND FOR DIFFERENT PURPOSES

There are several descriptions and relics that testify to the importance of sound in ancient ceremonies and structures, but it is only now that we are becoming aware of the extent that it was incorporated. Recent investigations into Paleolithic cave art have revealed an association between areas that produce a strong resonance and the location of the art. This finding demonstrates that the properties of sound were being recognized, explored, appreciated, and recorded more than thirty thousand years ago.

Long-Distance Communication—From Telepathy to Telephony

Long-distance communication using sound is nothing new for humans, and ways of transmitting sound without electricity goes back to deep antiquity. A more recent well-known form is yodeling, a method of relaying messages and communicating across the vast mountains and valleys of the Alps.

It is interesting to speculate about other means of communication. In our age of wireless devices for communication between humans we take very much for granted the high technology and unseen forces behind the function. Just for basics, for every voice or data transmission that takes place, a very specific set of parameters and conditions must exist for the connection to be made. If the correct frequency is not used and known on both ends, if the power is insufficient for the signal to travel, if a sender is not in place to set up or initiate, or a recipient is not in place to accept and receive, the communication will not occur. So not only must a medium exist for the transmission to travel through, there must be someone at each end intending and expecting communication to take place. It would seem natural to believe a similar set of parameters would be required for any such “wireless” communication to take place between any great distance and even realms of reality, time, or existence.

On a more practical level, could a relay system have been set up using sound as a way of communicating and sending messages across the Mediterranean Sea? I considered two locations for the southern relay points: the temple city of Malta, ninety-six miles south of Sicily, and Lampedusa, a small island off the coast of Tunisia in North Africa, considered the most southern part of Italy and the nearest landfall south of Malta. I searched to discover if any megalithic remains could be found on that tiny island. It turns out there are unresearched prehistoric megalithic ruins found on Lampedusa, some located on the northeast shore, overlooking the Mediterranean and facing toward Malta some one hundred miles away. No one can say if they are related to the Maltese temple culture, but the circular aspect of the Lampedusa constructions seems reflective of the Maltese temples.

Could sound be sent over the sea from the Lampedusa temples to the temples in Malta? Considering that sound seems to be amplified when it travels over water due to how cool air bends sound and thus increases its amplitude, it may not seem so farfetched. It is a strange effect that follows the principles of sound and wave motion.

The reason is that the water cools the air above its surface, which then slows down the sound waves near the surface. This causes refraction or bending of the sound waves, such that more sound reaches someone in a boat or across a body of water. Sound waves skimming the surface of the water can add to the amplification effect if the water is calm. That means sound would tend to focus and thus increase its apparent loudness.

Is it possible that the Malta complexes were used as generators of high-frequency acoustic waves? Perhaps they were used to arrange a communication channel among various islands. Legends abound around Malta of the Sirens acoustically tempting or deafening seafarers. These “sirens” might have been the best singers with the strongest voices, namely obese or thick women, such as some modern opera stars. As noted, many statues of just such women have been discovered everywhere on Malta, including temples and standing on pedestals in the middle of complexes. We can speculate that the singing of these women modulated low-frequency signals, which were generated on opposite ends of temples (in windows and in doors), simply with a bell, or with vibrating metal plates, or even with a strong wind drafted through a wall opening.

The oval, multichambered configuration of the Maltese temples would allow signals formed from groups of air particles, before output, to be amplified in a second parallel opposite the oval spaces of the temple. This would be analogous to a resonator. This is supported by the fact that the massive coralline limestone blocks used for construction of the complexes are a very resonant material.

Sound as a Weapon

The power of sound has been demonstrated by opera singers, who have been known, on occasion, to shatter glass simply by producing the correct sound. This effect was presumably already understood with the story of the shattering of the walls of Jericho as written in the Old Testament: “The captain of the Host of the Lord came to Joshua before he stormed Jericho and told him to circle the city for six days, and seven priests shall blow seven trumpets of rams’ horns, and on the seventh day, when you hear the trumpets, all the people shall shout with a great shout and the city shall fall down flat” (Joshua 6:2–5).

Sound for Altering Consciousness and Communicating with Other Realms

It is well accepted in scientific circles that there is a correlation between the electroencephalographic (EEG) wave rhythms exhibited by the brain of a human and the state of consciousness of that being. Rhythms customarily found in the normal human adult when he is relaxed and his eyes are closed have a pulse frequency in the 7–14 hertz range and have come to be identified as alpha rhythms. Similarly, when a person is aroused and anxious, the rhythms exhibited fall in the 14–28 hertz range and are known as beta rhythms. A normal person in sleep exhibits delta rhythms in the 1.75–3.5 hertz range. Other brain wave rhythms that have been identified by researchers as being associated with various normal and abnormal states of consciousness are theta rhythms, 3.5–7.0 hertz, and gamma rhythms, 28–56 hertz. Further research has led to the identification and naming of three additional rhythms: omega, 0.875–1.75 hertz; epsilon, 56–112 hertz; and zeta, 112–224 hertz.

A variety of specific methods has been devised for stimulating the brain to exhibit specific brain wave rhythms and thereby alter the state of consciousness of the individual. So-called trance states are arrived at through many methods involving sound, such as chanting, drumming, and singing, just to mention a few.

In my 2006 paper on electromagnetism and the ancients (an updated version was published in my book, Lost Knowledge of the Ancients), I discussed how I had noticed a possible correlation between the architectural configuration of a temple on Malta and a radio-frequency propagation pattern (see figure 13.4). I wrote that through “the infant field of Radio Archeology I would suggest a series of experiments, conducted to scientific standards, to test and measure both transmit and receive propagation properties of prehistoric sites that meet certain specific criteria. Such tests should include accurately modeling structures and developing or adapting existing propagation prediction tools to account for building material properties. This, along with utilizing carrier-wave transmitters and spectrum-scanning receivers and software, as well as spectrometers and spectrum analyzers to determine propagation properties, could help determine if they are enhanced by the site locations and/or site configuration and construction materials.” To me it was a far-flung yet comprehensive approach to analyzing ancient sites in an entirely new way.

Fig. 13.4. Illustration showing the similarities of the Hagar Qim Temple compound layout compared to a typical eight hundred megahertz wireless antenna pattern

In 2014, Archaeoacoustics: The Archaeology of Sound, the first international conference on archaeoacoustics—the archaeology of sound—took place on Malta; it brought together experts and researchers from around the world to study and survey the acoustical and various energy properties of the ancient temples on Malta, a UNESCO World Heritage site.*14 These temples are considered the oldest freestanding buildings on Earth and are more than a thousand years older than the Egyptian pyramids or Stonehenge.

In conjunction with the conference, a team of specialists—each working in their own field—defined and executed independent but coordinated collection and analysis of data on the temples. During some of the research experiments healthy volunteers were measured and monitored for changes in brain activity, blood pressure, and skin temperature on exposure to natural sound stimulation and reverberant conditions. Data were collected from the sounding of voices, horn and shell instruments, primitive drums, and electrically generated tones.

Fig. 13.5. Photos showing the “lobe” construction of the Neolithic-era Hagar Qim and Mnajdra Temples on Malta

Fig. 13.6. Equinox alignment at a Maltese temple (a); the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum (b)

Visual impacts related to cymatics, or energy patterns of sound waves, may also be observed: sand on a drumhead, water in a pottery or stone vessel. Correlations were sought between these patterns and those found in the Stone Age art of the site. Does one reflect the other?

Architectural evaluation by an acoustic engineer and a concurrent digital acoustic and electromagnetic mapping of sites were also conducted. Observations were made by experts in a wide range of fields in order to augment the known archaeological data. Results were compiled in a book published in 2014.

Fig. 13.7. MRI images show regional brain activity changes from baseline conditions (no tone) to three frequencies of stimulation, indicating increases and decreases in activity.

Fig. 13.8. Sound energy patterns displayed in sand and through an electromagnetic wave propagation prediction for the Stonehenge site

The full study will take years, and the researchers hope to reveal the original intended purposes of these highly unusual structures, while shedding light and a better understanding on how and why ancient cultures controlled unseen energy forces, such as acoustical or electromagnetic energy, with architecture.

More on the Conference

The conference presenters were an extremely diverse scientific group: scholars and researchers from universities and institutes around the world, representing such fields as architecture, archaeology, anthropology, acoustics, cave art, musicology, neurology, psychology, forensics, and more. Specialists in one field were respectfully given a look into the mechanics of another, toward a more holistic understanding of the ancient world. The subject of archaeoacoustics was elevated from the perception of it as a “pseudoscience” to a legitimate emerging field of study.

Delegates were introduced to a physical facet of prehistory that has somehow managed to remain under the radar; reports and research in a variety of fields will now recognize the megalithic “Temple Culture” of Malta.

Below is a summary and small sampling of research abstracts from the more than forty presentations that took place over the four-day event.

Archaeoacoustics Analysis of an Ancient Hypogeum in Italy

by Paolo Debertolis (University of Trieste)

We studied the archaeoacoustic properties of an ancient hypogeum in Cividale del Friuli (north of Italy). Aside from the fanciful interpretations mixed with legends, it was hypothesized that during the Celtic age the Hypogeum was used as a depository of funerary urns. However, other researchers believe it was used as a prison during the Roman or Lombard period. But despite this historical information, this hypogeum presents some unexpected sound similarities to the widely known Ħal Saflieni hypogeum in Malta.

This hypogeum consists of various underground spaces below the surface, carved out of the conglomerate with different levels and branches. Its shape looks rough to the careless eye, but in reality despite the alterations over the centuries, the builders made full use of the shape of the rooms to take advantage of the resonance phenomenon, obtained during prayers and mystic songs. In particular resonance effects were detected in two of the six chambers, and these maintain the original shape, with an arched shape along the top. There is also a small truss on the end wall that seems to have been specifically built to tune up the room for a male voice singing or praying. The male voice is absolutely necessary to stimulate the resonate response phenomenon as the two chambers are tuned to 94 and 102 Hz. On several occasions a female voice was used, but it was insufficient to stimulate the structure.

Results show that archaeoacoustics is an interesting new method for reanalyzing ancient sites; it uses different study parameters to rediscover forgotten technology that operates on the human emotional sphere. The effect on the psyche of ancient people through the acoustic properties suggests the builders of these sites had knowledge of this process and probably used it to enhance their rituals.

Fear and Amazement

by Torill Christine Lindstrøm (University of Bergen) and Ezra Zubrow (University at Buffalo)

“Fear and amazement are a very potent combination,” said Maximus in the film The Gladiator.

And indeed, the sacred, in whatever form or expression it has, often implies some kind of exaggeration that can function as super-normal sign stimuli. Such exaggerations are connected to what can be perceived through our sensory apparatuses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, skin sensation, perception of pain, pressure, and temperature). In particular, sacred objects are commonly larger and more elaborate than their everyday counterparts, and sacred sounds stronger, more complex, and often different from sounds or music that are heard in everyday life. Such exaggerations can be very effective in creating an “impression” and a sense of awe. They also have mesmerizing properties, as they may contribute to inducing altered states of consciousness

With regard to sounds, three elements are characteristic of religious rituals.

- Sudden strong sound(s) followed by silence. This combination creates startle responses followed by relief, a combination known in psychological research to increase susceptibility, receptiveness, and compliance.

- Sounds that are strong and complex. Their effect is to be impressive, “otherworldly,” and they attract and absorb attention.

- Repetitive rhythmic sounds or slow continuous sounds. They are often used in meditative practices and in creating various trancelike states.

These three elements have psychological and psychoneurological concomitants and explanations. Given that people have wished to create such acoustic effects in order to experience certain auditory and psychological reactions, particular architectonic features of sacred buildings and sacred spaces can be explained.

An Interdisciplinary Approach: The Contribution of Rock Art for Archaeoacoustic Studies

by Fernando Coimbra (Center for Geohistory and Prehistory, Portugal)

The author starts his paper with a brief reference to Paleolithic “making sound” objects (not musical instruments), which constitute an unambiguous archaeological evidence of the use of sound in that period. The presentation is developed in two parts.

- Rock art iconography and archaeoacoustics

- Acoustics, phosphene forms, and rock art

In the first part some examples of the use of sound in Late Prehistory are presented, based on the rock art images of nonliterate societies in different countries and with different chronologies. In the second part, a theoretical approach regarding the interaction of sound, phosphene forms, and the resulting rock art imagery is proposed; for example, are paintings found in a Neolithic context (caves and hypogea)?

The presentation ends with a short practical exercise: listening for two minutes to a musical piece representing the “evolution” from original sound such as wind, thunder, rain, birds, drums, human vocalizations . . . till the beginning of early music . . . all of them early acoustics that may also have been related to rock art iconography.

Thirty Years of Research in the Sound Dimensions of Painted Caves and Rocks

by Iegor Reznikoff (University of Paris West)

Since 1983, we have studied the acoustics of painted mostly Paleolithic caves in Western Europe, North Norway, and the Urals. These studies have shown strong correlations between the location of paintings in a cave and the quality of the resonance of these locations. A statistical approach shows that this relationship cannot occur by chance alone. From the obtained results, it is possible to deepen our understanding of the meaning of prehistoric signs and paintings. The acoustic argument—namely the evidence of the use of sounds in relationship with painting—gives the best argument to support the ritual, possibly shamanic signification of Paleolithic Art. We have also studied the relationship between painted rocks and the acoustic quality of the space around (Finland, Southeast France); such studies have recently been made successfully in Spain and the United States. It’s interesting to mention that some pictures have been found because of the sound quality of the location of the pictures. These studies initiated more than thirty years ago have opened a new era in sound archaeology.

Temples of Music: The “Cuicacalli” and the “Calmecac,” the Ancient American Conservatories

by Maria Cristina Pascual (University of Kent, Berlin, Germany)

Musical education was of critical importance in the Mesoamerican cultures since most of the people’s ancestral memory was transmitted by the priests through song and recitation of their illustrated codices in their temples. Outside the buildings, in the streets, people held onto their traditions and customs with a routine musical performance that began every day at sunrise, uttered as an act of gratitude to the sun, as described by the Spanish chroniclers who were the first Occidentals to come in contact with these unknown cultures. In their most prominent celebrations of processions and ceremonies, architecture and sound acted together as the ornamental representation through which power and religion were displayed and demonstrated to the masses. The maintenance of the whole social fabric required a very well-geared structure of musical training—which were composed of the two-tiered institution—that encompassed the “Cuicacalli,” the conservatory for the regular citizens of the empire, and the “Calmecac,” an elite institution for those who received superior training in the transcendent matters of the empire, as music was, and were predisposed to become future priests.

The aim of the paper is to scrutinize the codices and chronicles and their references of the two temples of music par excellence, as well as more recent archaeological revelations, such as the buried Calmecac on Tenochtitlan, currently located under the quarters of colonial Mexico City. The pursuit will produce a more profound understanding of the building typology, which conjugates sound and stone, as well as the social, political, and religious implications they had in these ancient cultures.

Exploring Possibilities of Sound Instruments in Prehistory from a Maltese Perspective

by Anna Borg Cardona (Maltese Folklore Society)

The Maltese Islands’ rich prehistory is the legacy of an advanced civilization, which had the extraordinary ability to create monumental architecture, as well as sculpture, pottery, and works of art. In such a society one would also expect the sound/music elements to have played a part in daily life, even if merely for communication, alerting, and signaling.

Seeing that this was a society highly concerned with religion and burial of its dead, ritual surely would have been of great significance. Vocal or instrumental sound (or both) would have accompanied rituals inside or outside the Temple area and hypogea. And yet nothing recognized as a musical instrument has so far ever been excavated from Malta’s prehistory sites.

The Arundo donax pannt (cane), so crucial in the production of Malta’s traditional instruments, was already available to Neolithic man, as were large conch shells, smaller seashells, animal membranes, animal horns, bone, clay, and of course the Maltese limestone. Musical instruments could certainly have been made from all of these. Among these, perishable membranes and vegetable matter would not have survived in their original form, but they may still have left traces or suggestions of their existence.

From the perspective of an organologist and musical historian, Cardona explores the above materials in terms of their possible use as sound-producing objects within a prehistoric context. Particular reference is made to instruments produced on the islands and around the Mediterranean in an attempt to connect prehistory with historical and the more recent past.

Archaeoacoustics and 111 Hertz

by Flinton Chalk (musician, researcher, curator, London)

In 1996, Cambridge University and Princeton University published the results of acoustic testing on a selection of man-made European Stone Age chambers dating from the fourth millennium BCE, the majority of which were in Ireland. The aim was to discover the resonant frequency of each chamber. The results fell within a very narrow band of acoustic wavelengths, between 95 hertz and 120 hertz. The average resonant frequency of the acoustically tested chambers was found to be 111 hertz. Once this frequency is emitted in the chamber the effect is to immerse the listener in sound; in this instance the sole frequency of 111 hertz is amplified by the architecture as it filters out other frequencies, creating an acoustic standing wave.

Many of us have experienced the effect of a standing wave while singing in a tiled bathroom. When a frequency is accidentally sung that correlates with the dimensions of the tiled bathroom, that tone will create a momentary standing wave that causes a booming or “immediate echo” sensation. This is a demonstration of how the brain experiences this immersive standing wave. We are able to recreate this immersive experience electronically in our installations; 111 hertz is a lower male baritone in the human vocal range and can be comfortably hummed, sung, or spoken.

Subsequent research has established the potentially beneficial medical attributes of the frequency of 111 hertz. This audible frequency is reputed to be processed by and therefore directly stimulated by the right-hand frontal cortex of the brain, a problem area for autism and other emotional and development disorders such as anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). This specific frequency is also associated with endorphin release, a potential nonaddictive panacea for pain relief.

It has been observed that within a few minutes of exposure to 111 hertz, alpha state trance is induced in the listener, as neuronal activity moves within the brain from the left-hand frontal lobe to the right. At that point the language centers are “quietened” along with increased theta wave activity normally associated with sleep and cell regeneration, produced solely in the right-hand prefrontal cortex. The overall effect is a subtle, altered state of consciousness with the potential to train the brain to stimulate longer-term neuronal activity in the right-hand hemisphere of the brain.

Enough evidence has now been gathered to compel further research, and discussions are underway with Cambridge University to instigate clinical trials.

Personally, I envision an Energy Survey Project (ESP) that proposes a methodical approach to surveying energy wave propagation properties of ancient architecture around the world and the associated measured physiological effects on humans. It seems the unique capabilities of advanced in-building propagation prediction software, test and measurement equipment, as well as brain-mapping technology and capabilities, are ideally suited and could be leveraged to accomplish an array of archaeological experiments and much more, by accurately modeling important sacred structures from Malta to Stonehenge, to the other great sacred sites and cathedrals worldwide, many of which still hold unseen secrets awaiting discovery. And we are just now beginning to learn new ways of how to look and learn.

In an interesting twist of local interest to NEARA, it should be noted there were reports from the mid-1950s and 1970s, from the Early Sites Research Society, submitted by James P. Whittall (1976) and archaeologist Frank Glynn (1955), comparing specific construction design aspects and techniques between the megalith temples on Malta and the “America’s Stonehenge” site in North Salem, New Hampshire. Interestingly, many close parallels and correlations were identified. I wonder if the chambers, passages, and portals of the New England site have ever had their acoustic properties tested. (Thanks to Polly Midgley for that.)

Thoughts on My Hypogeum Experience

by Glenn Kreisberg

As a spectrum engineer my interest in conducting an on-site survey of the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum in Malta was to gather data to accurately model the architectural features of the underground structure. Accurately modeling the physical space and all its unusual dimensions would allow for wave propagation prediction models to be generated using variable inputs, such as frequency, level of energy, structure materials, and location. Based on the floor plan layout of this ancient subterranean necropolis, output maps could be produced that would allow for visualization of the energy footprint from an energy source. The intent is to apply the same methodology used for in-building wireless network design to better understand how energy waves behave when interacting with the stone construction and architectural features of the Hypogeum.

Preliminary modeling based on photographs and floor plan diagrams confirmed previous research, which suggested that the room known as the Oracle Chamber has characteristics that apparently project sound energy in a highly focused manner, allowing the audio waves to easily distribute to the other areas and rooms in the large, multilevel complex. Was there something specific—a feature or aspects of the design—that could account for such an effect? Was it intentional and planned for in the original construction design?

As part of the Archaeoacoustics: The Archaeology of Sound conference held in February 2014, on Malta, I was part of a multidisciplinary team gathered to conduct research. We were granted permission to carry out a series of experiments in the Hypogeum under controlled conditions and collect data for further analysis.

Upon entering the Hypogeum I was struck by the curved nature of the walls, pillars, stairways, and ceilings, with no sharp corners, edges, or surfaces. Not unlike the aboveground temples of Malta, many of the lines are circular, which creates numerous, continuous, opposing parallel surfaces. Everything seemed carved or worn smooth, almost as if slightly polished, perhaps the result of water running over the surfaces for a long period of time. The effect on propagating waves this curving smoothness plays is that it prevents refraction or the bending of waves when they encounter a sharp or jutting surface. Think how ocean waves “turn” or bend when encountering a jutting peninsula, as they break toward the shore. Refraction breaks down and weakens waves (water, sound, or electromagnetic) and is unlike reflection. The many parallel, opposing surfaces of the Hypogeum cause reflection, which allow the sound waves generated within to echo, build upon themselves, and reverberate strongly.

The Oracle Chamber ceiling, especially near its entrance from the outer area and the elongated inner chamber itself, appears to be carved into the form of a waveguide. A waveguide is a structure that guides waves, such as sound waves or electromagnetic waves. There are different types of waveguides for different type of waves. As a rule of thumb, the width of a waveguide needs to be of the same order of magnitude as the wavelength of the guided wave. So high-frequency small waves require a small waveguide, and low frequencies with larger wavelengths would require a larger waveguide. The very low-frequency sounds that echo strongest in the Hypogeum have very long wavelengths; thus the waveguide employed would need to be quite large. I believe the Oracle Chamber’s size itself is of the magnitude to create the wave-guiding effect on the sound waves produced within.

Fig. 13.9. Carved “waveguide” ceiling channel feature at entrance to the Oracle Chamber in the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum

That the Oracle Chamber in the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum in Malta acts as a waveguide for sound waves seems indisputable and that it was carved that way by humans thousands of years ago is quite remarkable to contemplate. Does this constitute evidence that sound provided the earliest link in architecture between form and function? It may have served a Neolithic belief system to have sound behave the way it does in the Hypogeum, and those who created it apparently had the sophistication and ingenuity in their design skills and construction techniques to undertake this exceptional and complicated expression of sound in stone.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES

“Of Temples and Goddesses in Malta” by Linda Eneix. From Popular Archaeology. popular-archaeology.com/issue/april-2011/article/of-temple-and-goddesses (accessed January 18, 2018).

“Outdoor Sound Propagation in the U.S. Civil War” by Charles D. Ross. From the Echoes newsletter. http://asa.aip.org/Echoes/Vol9No1/EchoesWinter1999.html (accessed September 6, 2017).

Homepage for Megalithic-Lampedusa.com. www.megalithic-lampedusa.com (accessed September 6, 2017)

Homepage for fractal artist, author, and publisher Gregory Sams. www.gregorysams.com (accessed September 6, 2017).