CHAPTER 19

CONCLUDING BY LOOKING FORWARD

I think that only daring speculation can lead us further and not accumulation of facts.

ALBERT EINSTEIN

I should start this chapter by saying that I am neither a scholar nor a scientist, but I believe in the scientific method. I also believe that true breakthroughs in science occur when speculation pushes us to the limits of what we perceive as possible and beyond. Surprises and mysteries abound in the natural world. When the true form and nature of the universe is known, or more known than it is today, it should not be surprising if that form is something familiar to us, having been seen before and created by the forces of nature. The natural forces at play in nature on Earth—wind, rain, fire, friction, erosion, the applied forces of physics—all shape our natural world, our universe. The way bubbles and foam multiply rapidly in the backwater eddy of a stream may turn out to resemble the true nature of what our multiverse looks like. This thought represents my own personal expression of a belief. In examining the mute stone constructions of past, preliterate, and prehistoric cultures, our job is to understand the thoughts and thought processes of the people responsible. Interpreting their expressions in stone can open a window into their belief systems and the personal expressions that make up those systems.

Looking ahead forty years, the future holds a new perspective.

One of the biggest changes we’ll see in the future will be a shift in perspective. Evidence for this paradigm change is already present in the headlines today. Trends in current research are already curving toward the realization that prehistoric human beings (including, in addition to us “Homo moderns,” Home erectus and Homo neanderthalensis) were considerably more intelligent and innovative than they are generally given credit for within most orthodox-thinking scientific and historical research circles. This change in perception will correct a bias that does a great disservice to the abilities and accomplishments we moderns generally have attributed to our ancestors. This change in how we perceive ancient man is underway and will continue into the future.

Eurocentricity is another persistent bias that is quite prevalent within the fields of anthropology and history. Both fields are dominated by a heavily anglicized intellectual culture: most of the leading scholars in those fields are of European origin or ancestry. Consequently, Caucasian culture is frequently considered the norm by which all others are measured. In the future, scholars will tackle this bias, and I believe a key objective of future ancient mysteries research will be to remove the “Anglo-colored lenses” that are unconsciously worn by many North American and European researchers and scholars. (Many chroniclers of old wore them as well.) These biased lenses often filter out important details about the stories of our past—details whose inclusion just might help us to see a more complete picture about the history of who we are and from where we came.

Communication tools of the future will help address this sensitive issue and others by ensuring that non-European-language-speaking researchers from around the world can easily contribute their valuable insights, knowledge, and research data to the collective pieces of the ancient mysteries puzzle constructed on a playing field leveled by a net-neutral, open-source, equal-access Internet and World Wide Web.

Another shift in perception can occur by recognizing that many modern discoveries are actually rediscoveries of lost knowledge from past civilizations. Embracing this realization will help us begin to better contextualize, within the bigger picture of human knowledge, the achievements and events of the past, giving rise to a fundamental understanding of where our present time fits into the past and the future, into the cycle of human existence. Research and evidence will eventually combine to create a bigger picture and connect the dots, so to speak, for a public eager to discover that the whole picture adds up to much, much more than the sum of its parts.

Forty years from now, I would dare to speculate, using much of the evidence and tools that already exist today, many of the mysteries we are studying hard in this day and age will have been resolved. Among those mysteries is one this book seeks to answer: Who built the lithic sites in the Northeast and for what purpose? Perhaps the future holds proof once and for all that the Northeast’s Native civilization not only built in stone but also aligned their lithic structures to the sky and the horizon, as did every other ancient civilization worldwide in ancient times.

LESSON IN STONES

What important messages can some of these sites hold if we learn to read them and hear what they have to say? How can heeding their messages, or ignoring them, directly affect our personal and community well-being, harmony, and balance in a very tangible way? In Japan, ancient standing stones held a message long ignored. In 2011, a tsunami that hit northeastern Japan had a devastating effect along the coastline and inland. Headlines after the event reported about missed warnings: Existing for hundreds of miles along the coast in the affected region were a network of ancient inscribed megalithic monuments that had been erected and maintained over long periods of time, the most recent dating from about six hundred years ago. In effect, these stones offered a type of primitive early warning system along the coast, if you heeded their message.

Fig. 19.1. The 2011 Japan tsunami. Some of the resulting damage could have been avoided if the warning on ancient standing stones had been heeded.

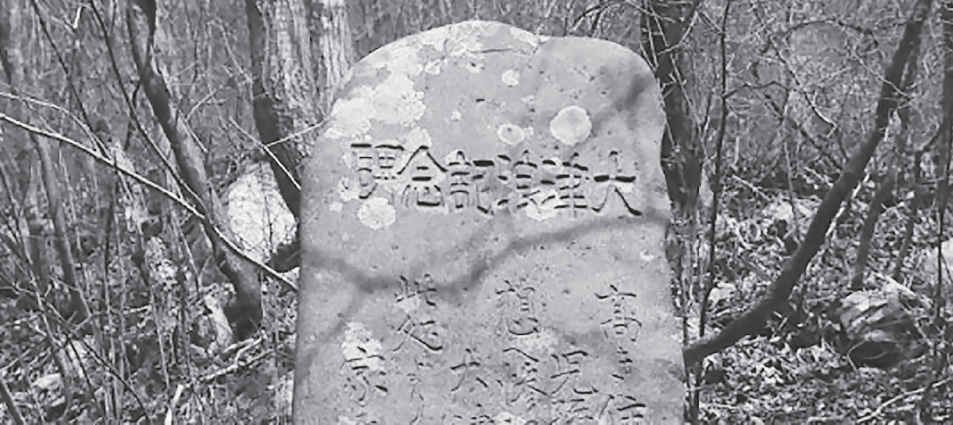

Fig. 19.2. Inscribed megalithic stone in Japan

Fig. 19.3. Warning message inscribed on a megalithic stone in Japan

It turns out the people’s ancestors had left monuments to remind them of the dangers. The inscriptions are said to read, “To live in peace and tranquility (balance and harmony), for generation upon generation, one must heed this warning, do not build your dwellings beyond this marker.”

To not spend the effort and energy to investigate important ceremonial stone sites and landscapes to fully understand and interpret the true meaning and story behind them and the balance and harmony they help create is to our own peril.

At the time of this writing, there is a movement building in America, supported by a broad spectrum of American activists who are speaking out. They are standing with Standing Rock. The Standing Rock Sioux tribe in South Dakota is currently fighting a battle to save sacred lands and sacred sites from the development of an oil pipeline through their lands. The pipeline threatens not only to destroy the tribe’s source of fresh drinking water but also to desecrate the sacred sites of their ancestors, of all our ancestors. The symbol of the “standing rock” serves as a metaphor: one of strength, perseverance, and human integrity. Those who stand with those at Standing Rock are on the right side of history in terms of humanity, integrity, and doing the right thing.

The message held in the standing stones, in the carefully constructed stone cairns, in the animated existence of snake and turtle effigies of stone, and in the alignments of these sites with the heavens and the waters in the earth below is the message of integrity, the root of which is to “integrate.” When we visit and study these sites, it forces us, knowingly or not, to open our minds and hearts to a higher truth, a truth seeking balance and harmony in our lives and in our world, a truth seeking integrity in our existence. When we visit these sites we are joined in body, mind, and spirit; these elements are integrated, thus giving us integrity. When we can understand the true message the silent stones speak, we are offered the opportunity to become integrated with our higher spirit.

FURTHER COMMENTS ON THE ROCK STRUCTURES

Connecticut woods wanderer and NEARA researcher Doug Schwartz provided a wealth of research insight when he responded to a curious query and replied with a comprehensive list of substantiating evidence and references from the past and provided here.

Doug Schwartz

In response to a legitimate question, I wish to respond by stating that this question would never have been asked a century ago. This is in no way intended to slight the questioner, because it is a question which has been asked time and time again in recent decades, often without being answered properly. The archaeological community in the eastern U.S. has collectively forgotten what was known to most people in the first three centuries of European settlement.

The stone cairns in the Southeast are identical to the stone cairns in the Northeast, and the extant examples of the latter now number easily in seven figures. Most mark Native burials, and this practice survived long after contact, and there is an extensive literature supporting this, a small portion of which is appended below. I will let this literature speak for itself, only adding the observations that this custom was found throughout all of North America east of the Mississippi (I don’t know if it extended farther west, but I suspect it did), and while the Mississippian culture is generally thought of as a society, which used earth as its architectural medium, stone was equally popular.

I have seen many, many thousands of Native cairns, but have yet to encounter post-contact field clearings which might be confused with these. Field clearings are easy to differentiate. They are either an amorphous heap at the edge of the field or incorporated into the stone walls encompassing the field. Native cairns are often found in out-of-the-way places where no one ever farmed, often on mountains or overlooking waterfalls (not all Native cairns are burials, many served other purposes).

I would add that I find the excavation of such cairns to be despicable grave robbing and would hope that any who read this respect the intentions of their builders and just leave them alone. We are now in a damned-if-wedo and damned-if-we-don’t situation. If we tell people what they are, they risk being ransacked; if we don’t, time and time again they are demolished as useless “field clearings” having no enduring value.

Thomas Jefferson, from

Notes on the State of Virginia, 1787

Barrows, of which many are to be found all over this country. These are of different sizes, some of them constructed of earth, and some of loose stones. That they were repositories of the dead, has been obvious to all. . . . But on whatever occasion they may have been made, they are of considerable notoriety among the Indians; for a party passing, about thirty years ago, through the part of the country where this barrow is, went through the woods directly to it, without any instructions or enquiry, and having staid about it some time, with expressions which were construed to be those of sorrow, they returned to the high road, which they had left about half a dozen miles to pay this visit, and pursued their journey.

John Lawson, from

Lawson’s History of North Carolina, p. 22

[The Santee of South Carolina] have other sorts of Tombs, as where an Indian is slain, in that place they make a heap of stones, (or sticks where stones are not to be found); to this memorial every Indian that passes by adds a stone to augment the Heap, in respect to the deceased hero.

E. G. Squier, from

“Antiquities of the State of New York”

Rude heaps of stone of similar character are of frequent occurrence throughout the west. A very remarkable one occurs upon the diving ridge between Indian and Crooked creeks, about ten miles southwest of Chillicothe, Ohio. It is immediately by the side of the old Indian trail, which led from the Shawnee towns, in the vicinity of Chillicothe, to the mouth of the Scioto River, and consists of a simple head of stones, rectangular in form, and measuring one hundred and six feet in length by sixty in width, and between three and four in height. The stones are of all sizes, from those not larger than a man’s head, to those which can hardly be lifted. They are such as are found in great abundance on the hill slopes—the fragments or debris of the outcropping sandstone layers. Some are water-worn, showing that they were brought up from the creek, nearly half a mile distant: and although they were disposed with no regularity in respect to each other, the heap was originally quite symmetrical in outline. . . . The heap is situated upon the highest point of land traversed by the Indian trail: upon the water shed, or dividing ridge between the streams which flow into Brush creek upon the one side and the Scioto River on the other.

Another heap of stones of like character, but somewhat less in size, is situated upon the top of a high, narrow hill overlooking the small valley of Salt creek, near Tarlton, Pickaway County, Ohio. It is remarkable as having large numbers of crumbling human bones . . . . A very extensive prospect is had from this point. . . . Smaller and very irregular heaps are frequent among the hills. These do not generally embrace more than a couple of cart-loads of stone, and almost invariably cover a skeleton. Occasionally the amount of stones is much greater. . . . A number of such graves have been observed near Sinking Springs, Highland County, Ohio; also in Adams County in the same State, and in Greenup County, Kentucky, at a point nearly opposite the town of Portsmouth on the Ohio.

A stone heap, somewhat resembling those here described, though considerably less in size, is situated on the Wateree River, in South Carolina, near the mouth of Beaver Creek, a few miles above the town of Camden. It is thus described in a MS. letter from Dr. Wm. Blanding, late of Camden, addressed to Dr. S. G. Morton, of Philadelphia:

The land here rises for the distance of one mile, and forms a long hill from north to south. On the north point stands what is called the Indian Grave. It is composed of many tons of small round stones, from one to four and five pounds weight. The pile is thirty feet long from east to west, twelve feet broad, and five feet high, so situated as to command an extensive view of the adjacent country, as far as Rocky Mount, a distance of twenty miles above, and of the river for more than three miles, even at its lowest stages.

A large stone heap was observed, a number of years since, on a prairie, in one of the central counties of Tennessee. . . . Within it was found the decayed skeleton of a man.

Noting that there was (and still is forty years later) “a prevalent archaeological belief that there are no prehistoric mounds or structures in New England,” Frank Glynn excavated two stone mounds in Westbrook, Connecticut, and noted the differences in them.

Frank Glynn, from

“Excavation of the Pilot’s Point Stone Heaps”

The Indian stone heaps of Connecticut fall into three size groups.

Large: This may be exemplified by the site at the former Stott Farm in Jewett City, Connecticut. Made up largely of broken stones, it has an approximate diameter of 45 feet, and an elevation of seven feet. Although a heavy concentration of stones, it has been known locally as an Indian Stone Fort. Two heaps of similar size, but oval rather than circular, have been reported by the Danbury Chapter from their locality.

Medium: This intermediate type is of oval shape with the long axis East and West. It has low elevation, one to three feet. Length varies from fifteen to twenty-odd feet. . . .

Small: The smallest type varies from cones six to eight feet in diameter to small piles comparable to hog-backed earth burials found in . . . historic Indian burial grounds . . . . James Hammond Trumbull noted that [Indian stone heaps] were formerly very common in Connecticut [Trumbull 1881]. Ezra Stiles, for whom a strong claim could be made as the first American archaeologist, took a continued interest in the heaps.

The two stone heaps Glynn excavated overlooked Long Island Sound and “consisted of oval heaps of stone with a width of twelve feet, a length of twenty-one feet, the long axis East and West.” Glynn noted that on the point where the cairns were located “hurricanes ‘Carol’ and ‘Edna’ in 1955 washed out soil on the northern slope, disclosing a hitherto unknown well. Its top is washed by average high tides. It may be of Indian origin.” Glynn found that

Stone Heap I, the larger of the two heaps, was a 12 foot by 21 foot oval mound with a maximum elevation of two feet. . . . Stone Heap I . . . proved to be the far more interesting of the pair . . . . After the loose stone overburden was removed, a unique and complex site was revealed. There was a well-defined outer wall, outside of which a complete humus horizon had formed. Within the wall was a three-inch layer of black clay, which was covered by a stone pavement, with hearths, fire-pits and postholes below. Above it was a compact deposit of burned stones and fine charcoal, also containing stone hearths and postholes.

There was a five-foot-deep pit under the pavement at the eastern end. Above the fire-scorched soil in the bottom of the pit was a layer of black soil like that on the stone pavement. Above this black soil was gravel refill which reached to the pavement. A ring of small cobbles, set vertically, outlined the pit’s circumference in the pavement. In the black soil above the pavement large boulders, including two quarried granite slabs, were embedded.

In and immediately above the pavement were found stemmed and barbed projectile points, a stemmed knife, a scraper and a chisel, suggestive of the Archaic-Woodland overlapping periods. . . . Twenty features, other than artifacts and pot sherds, were encountered. . . . [These included] two small stone-ringed hearths, one superimposed upon the other . . . a stone ringed hearth, eighteen inches in diameter [various hearths and fire-pits containing stone items, and at] the focal point of the mound . . . two rectangular stone slabs . . . vertically placed . . . were well embedded in the black deposit . . . . [of a pit that was] circular, four feet, ten inches in diameter and five feet, three inches deep . . . [with] a closely fitted floor, chiefly slab-like pieces of stone.

Glynn required more than one page of fine type to describe the various features unearthed in the interior of the cairn.

David Bushnell Jr., from

“Native Cemeteries and Forms of Burial East of the Mississippi”

Cairns, heaps of stones usually on some high and prominent point, are found throughout the southern mountains, but seldom have they been mentioned in the older settled parts of the North. One, however, stood in the country of the Housatonic Indians. As early as 1720 some English traders saw a large heap of stones on the east side of Westenhook or Housatonic River, so called, on the southerly end of the mountain called Monument Mountain, between Stockbridge and Great Barrington. This circumstance gave rise to the name which has ever since been applied to the mountain, a prominent landmark in the valley.

E. O. Dunning, from

“Account of Antiquities in Tennessee”

Stone mounds are quite numerous, not only on the hills once occupied by the Cherokee, but far northward. Many of the western towns of the Cherokee, often termed the Overhill Towns, were in the vicinity of Blout County, Tennessee. Many stone mounds were there on the hilltops, and these may justly be attributed to the Cherokee, but all may not have covered the remains of the dead. Leaving Chilhowee Valley and crossing the Allegheny range toward North Carolina, in a southeast course, having Little Tennessee River on my right, and occasionally in sight from the cliffs, my attention was called along the road, to stone heaps. . . . After an examination of the objects and a talk with Indians and the oldest inhabitants, I came to the conclusion that there were two kinds of these remains in this part of Tennessee, which are sometimes confounded, viz, landmarks, or stone piles, thrown together by the Indians at certain points in their journeys, and those which marked a place of burial. At a pass called Indian Grave Gap, I noticed the pile that has given its name to the mountain gorge. The monument is composed simply of round stones raised three feet above the soil, and is six feet long and three wide.

As the grave had been disturbed I could make no satisfactory examination of its contents. On the opposite side of the Gap, a stone heap of another description was observed, which had been thrown together in accordance with Cherokee superstition that assigns some good fortune to the accumulation of those piles. They had the custom, in their journeys and war-like expeditions, at certain known points, before marked out, of casting down a stone and upon the return another. . . .The Cherokee custom of burying the dead under heaps of stone, it is well known, was practiced as late as 1730.

James Adair, from

The History of the American Indians, p. 184

Note: Part of the extremely long subtitle to this book reads: “Particularly Those Nations Adjoining to the Missisippi [sic], East and West Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia: Containing an Account of their Origin, Language, Manners, Religious and Civil Customs, Laws, Form of Government, Punishments, Conduct in War and Domestic Life, Their Habits, Diet, Agriculture, Manufactures, Diseases and Method of Cure . . .” In the text, Adair writes:

To perpetuate the memory of any remarkable warriors killed in the woods, I must here observe that every Indian traveler, as he passes that way, throws a stone on the place, according as he likes or dislikes the occasion or manner of death of the deceased. In the woods we often see innumerable heaps of small stones in these places, where, according to tradition, some of their distinguished people were either killed or buried, till the bones could be gathered; then they add Pelion on Ossa, still increasing each heap, as a lasting monument and honor to them, and an incentive to great actions.

Stephen Williams, from

Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory. p. 171

About ten miles south of Newark [Ohio] on the border of Licking County was the site of the Great Stone Mound, once probably some fifty feet tall, not an unlikely estimate. By 1860 people were talking about where and how tall it had been since it had been destroyed for its stone fill decades before, in 1831–32. How big was it? It seems that over ten thousand wagonloads of fill, mainly stones, were carried off to make a dam.