Chapter 2

The First Decade 1920–1929

‘It was while I was working in the dispensary that I first conceived the idea of writing a detective story.’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

The Mysterious Affair at Styles • The Mystery of the Blue Train

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in the USA at the end of 1920 and in the UK on 21 January 1921. It is a classic country-house whodunit of the sort that would eventually become synonymous with the name of Agatha Christie. Ironically, over the following decade she wrote only one more ‘English’ domestic whodunit, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). The other two whodunits of this decade are set abroad – The Murder on the Links (1923) is set in Deauville, France and The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928) has a similar South of France background. With the exception of the last title, which Christie, according to her Autobiography, ‘always hated’ and had ‘never been proud of’, they are first-class examples of the classic detective story then entering its Golden Age. Each title, with the same exception, displays the gifts that would later make Agatha Christie the Queen of Crime – uncomplicated language briskly telling a cleverly constructed story, easily recognisable and clearly delineated characters, inventive plots with all the necessary clues given to the reader, and an unexpected killer unmasked in the last chapter. These hallmarks would continue to be a feature of Christie’s books until the twilight of her career, half a century later.

The rest of her novels of the 1920s consist of thrillers, both domestic – The Secret Adversary (1922), The Secret of Chimneys (1925) and The Seven Dials Mystery (1929) – and international – The Man in the Brown Suit (1924). While none of these titles are first-rate Christie, they all exhibit some elements that would appear in later titles. The Secret Adversary, the first Tommy and Tuppence adventure, unmasks the least likely suspect while The Man in the Brown Suit is an early experiment with the famous Roger Ackroyd conjuring trick. The Seven Dials Mystery subverts reader expectation of the ‘secret society’ plot device and The Secret of Chimneys, a light-hearted mixture of missing jewels, international intrigue, incriminating letters, blackmail and murder in a high society setting, shows early experimentation with impersonation and false identity.

Throughout the 1920s Christie’s short story output was impressive. She published three such collections in the decade. The contents of Poirot Investigates (1924) first appeared in The Sketch, in a commissioned series of short stories, starting in March 1923 with ‘The Affair at the Victory Ball’. By the end of that year two dozen stories had appeared and 50 years later the remainder of these stories had their first UK book appearance in Poirot’s Early Cases. In 1953 Christie dedicated A Pocket Full of Rye to the editor of The Sketch, ‘Bruce Ingram, who liked and published my first short stories.’ In 1927, at a low point in Christie’s life, after the death of her mother and her own disappearance, The Big Four was published. This episodic Poirot novel, consisting of a series of connected short stories all of which had appeared in The Sketch during 1924, can also be considered a low point in the career of Hercule Poirot as he battles with a gang of international criminals intent on world domination. The last collection of the decade is the hugely entertaining Partners in Crime (1929). These Tommy and Tuppence adventures, most of which had appeared in The Sketch also during 1924, were pastiches of many of the crime writers of the time – ‘The Man in the Mist’ (G.K. Chesterton), ‘The Case of the Missing Lady’ (Conan Doyle), ‘The Crackler’ (Edgar Wallace) – and, while light-hearted in tone, contain many clever ideas.

Apart from her crime and detective stories, tales of the supernatural, romance and fantasy all appeared under her name in many of the multitude of magazines that filled the bookstalls. Many of the stories later published in the collections The Mysterious Mr Quin, The Hound of Death and The Listerdale Mystery were written and first published in the 1920s. And, of course, it was during the 1920s that Miss Marple made her first appearance, in the short story ‘The Tuesday Night Club’, published in The Royal Magazine in December 1927. With the exception of the final entry, ‘Death by Drowning’, the stories that appear in The Thirteen Problems were all written in the 1920s and appeared in two batches, the first six between December 1927 and May 1928, and the second between December 1929 and May 1930. In 1924 her first poetry collection The Road of Dreams was published. And it seems likely that her own stage adaptation of The Secret of Chimneys was begun in the late 1920s, as was the unpublished and unperformed script of the macabre short story ‘The Last Séance’.

The other important career decision taken in 1923 was to employ the services of a literary agent, Edmund Cork. The first task undertaken by Cork was to extricate Christie from a very one-sided contract with The Bodley Head Ltd and negotiate a more favourable arrangement with Collins, the publisher with which she was destined to remain for the rest of her life; as, indeed, she did with Edmund Cork.

Three of the best short stories Christie ever wrote were published during this decade. In January 1925 ‘Traitor Hands’, later to achieve immortality as the play, and subsequent film, Witness for the Prosecution, appeared in Flynn’s Weekly. The much-anthologised ‘Accident’ was published in the Daily Express in 1929; this was later adapted by other hands into the one-act play Tea for Three. And ‘Philomel Cottage’, which spawned five screen versions as Love from a Stranger, appeared in The Grand in November 1924.

Finally, the first stage and screen version of her work appeared during the 1920s. Alibi, adapted for the stage by Michael Morton from The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, opened in May 1928 while the same year saw the opening of films of The Secret Adversary – as Die Abenteuer G.m.b.h. – and The Passing of Mr Quinn, based loosely on the short story ‘The Coming of Mr Quin’.

This hugely prolific decade shows Christie gaining an international reputation while experimenting with form and structure within, and outside, the detective genre. Although her first novel was very definitely a detective story, her output for the following nine years returned only three times to the form in which she was eventually to gain immortality.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

21 January 1921

Arthur Hastings goes to Styles Court, the home of his friend John Cavendish, to recuperate during the First World War. He senses tension in the household and this is confirmed when his hostess, John’s stepmother, is poisoned. Luckily, a Belgian refugee staying nearby is an old friend, a retired policeman called Hercule Poirot.

In her Autobiography Agatha Christie gives a detailed account of the genesis of The Mysterious Affair at Styles. By now, the main facts are well known: the immortal challenge – ‘I bet you can’t write a good detective story’ – from her sister Madge, the Belgian refugees from the First World War in Torquay who inspired Poirot’s nationality, Christie’s knowledge of poisons from her work in the local dispensary, her intermittent work on the book and its eventual completion, at the encouragement of her mother, during a two-week seclusion in the Moorland Hotel. This was not her first literary effort, nor was she the first member of her family with literary aspirations. Both her mother and sister Madge wrote, and Madge actually had a play, The Claimant, produced in the West End before Agatha did. Agatha had already written a ‘long dreary novel’ (her own words in a 1955 radio broadcast) and some short stories and sketches. While the story of the bet is realistic, it is clear that this alone would not be stimulus enough to plot, sketch and write a successful book. There was obviously an innate gift and a facility with the written word.

Although she began writing the novel in 1916 (The Mysterious Affair at Styles is actually set in 1917), it was not published for another four years. And its publication was to demand consistent determination on its author’s part as more than one publisher declined the manuscript. Eventually, in 1919, John Lane, co-founder of The Bodley Head Ltd, asked to meet her with a view to publication. But, even then, the struggle was far from over.

The contract, dated 1 January 1920, that John Lane offered her took advantage of Agatha Christie’s publishing naivety. She explains in her Autobiography that she was ‘in no frame of mind to study agreements or even think about them’. Her delight at the prospect of publication, combined with the conviction that she was not going to pursue a writing career, persuaded her to sign. Remarkably, the actual contract is for The Mysterious Affair of (rather than ‘at’) Styles. She was to get 10 per cent only after 2,000 copies were sold in the UK and she was contracted to produce five more titles. This clause was to lead to much correspondence over the following years.

Later, as her productivity, success and popularity increased and she realised what she had signed, she insisted that if she offered a book she was fulfilling her side of the contract whether or not The Bodley Head accepted it. When they expressed doubt as to whether Poirot Investigates, as a volume of short stories rather than a novel, should be considered part of the six-book contract, the by now confident writer pointed out that she had offered them the non-crime Vision, described in Janet Morgan’s Agatha Christie: A Biography as a ‘fantasy’, as her third title. The fact that her publisher had refused it was, as far as she was concerned, their choice. It is quite possible that if John Lane had not tried to take advantage of his literary discovery she might have stayed longer with The Bodley Head. But the prickly surviving correspondence shows that those early years of her career were a sharp learning curve in the ways of publishers – and that Agatha Christie was a star pupil. Within a relatively short space of time she is transformed from an awed and inexperienced neophyte perched nervously on the edge of a chair in John Lane’s office to a confident and business-like professional with a resolute interest in every aspect of her books – jacket design, marketing, royalties, serialisation, translation and cinema rights.

The readers’ reports on the Styles manuscript were, despite some misgivings, promising. One gets right to the commercial considerations: ‘Despite its manifest shortcomings, Lane could very likely sell the novel. . . . There is a certain freshness about it.’ A second report is more enthusiastic: ‘It is altogether rather well told and well written.’ And another speculates on her potential future ‘if she goes on writing detective stories and she evidently has quite a talent for them’. The readers were much taken with the character of Poirot – ‘the exuberant personality of M. Poirot who is a very welcome variation on the “detective” of romance’; ‘a jolly little man in the person of has-been famous Belgian detective’. Although Poirot might take issue with the use of the description ‘has-been’, it was clear that his presence was a factor in the manuscript’s acceptance. In a report dated 7 October 1919 one very perceptive reader remarked, ‘but the account of the trial of John Cavendish makes me suspect the hand of a woman’. Because her name on the manuscript appears as A.M. Christie, another reader refers to ‘Mr. Christie’.

Despite these favourable readers’ reports, there were further delays and after a serialisation in The Weekly Times – the first time a ‘first’ novel had been chosen – beginning in February 1920, Christie wrote to Mr Willett at The Bodley Head in October that year wondering if her book was ‘ever coming out’ and pointing out that she had almost finished her second one. This resulted in her receiving the projected cover design, which she approved. Eventually, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published later that year in the USA. And, almost five years after she began it, Agatha Christie’s first book went on sale in the UK on 21 January 1921. Even after its appearance there was much correspondence about statements and incorrect calculations of royalties as well as cover designs. In fairness to John Lane and The Bodley Head, cover design and blurbs also featured regularly throughout her career in her correspondence with Collins.

As we have seen, one of the readers’ reports mentioned the John Cavendish trial. In the original manuscript, Poirot’s explanation of the crime is given in the form of his evidence in the witness box during the trial. In her Autobiography Christie describes John Lane’s verdict on her manuscript, including his opinion that this courtroom scene did not convince and his request that she amend it. She agreed to a rewrite and although the explanation of the crime itself remains the same, instead of giving it in the course of the judicial process, Poirot holds forth in the drawing room of Styles in the kind of scene that was to be replicated in many later books.

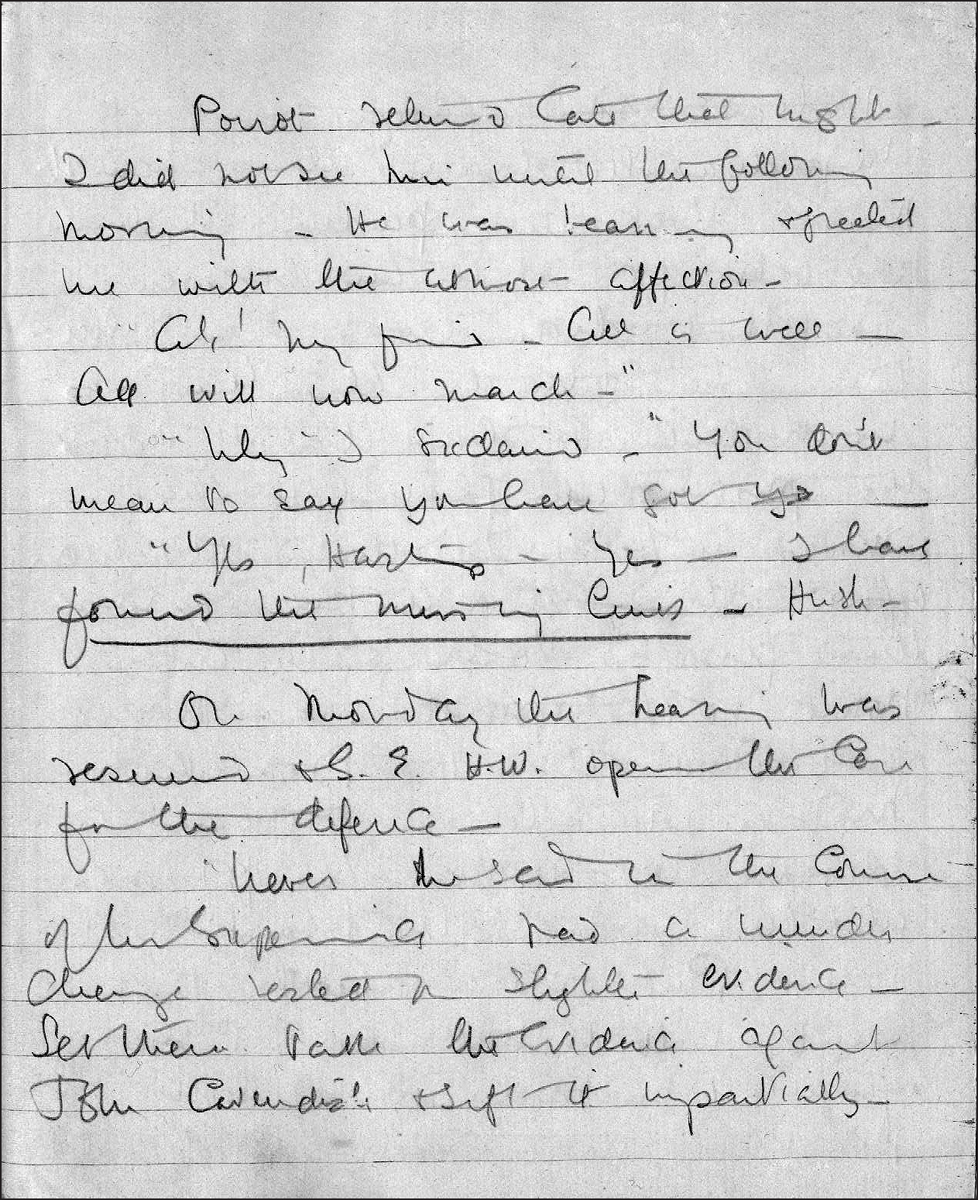

Incredibly, almost a century later – it was written, in all probability, in 1916 – the deleted scene has survived in the pages of Notebook 37, which also contains two brief and somewhat enigmatic notes about the novel. Equally incredible is the illegibility of the handwriting. It was written in pencil, with much crossing out and many insertions. This is difficult enough, but an added complication lies in the fact that Christie often replaced the deleted words with alternatives, squeezed in, sometimes at an angle, above the original. And although the explanation of the crime is, in essence, the same as the published version, the published text was of limited help. The wording is often different and some names have changed. Of the Notebooks, this exercise in transcription was the most challenging of all. The fact that it is Agatha Christie’s and Hercule Poirot’s first case made the extra effort worthwhile.

In the version that follows I have amended the usual Christie punctuation of dashes to full stops and commas, and I have added quotation marks throughout. I use square brackets where an obvious, or necessary, word is missing in the original; a few illegible words have been omitted. Footnotes have been used to draw attention to points of particular interest.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

The story so far . . .

When wealthy Emily Inglethorp, owner of Styles Court, remarries, her new husband Alfred is viewed by her stepsons, John and Lawrence, and her faithful retainer, Evelyn Howard, as a fortune-hunter. John’s wife, Mary, is perceived as being over-friendly with the enigmatic Dr Bauerstein, a German and an expert on poisons. Also staying at Styles Court, while working in the dispensary of the local hospital, is Emily’s protégée Cynthia Murdoch. Then Evelyn walks out after a bitter row. On the night of 17 July Emily dies from strychnine poisoning while her family watches helplessly. Hercule Poirot, called in by his friend Arthur Hastings, agrees to investigate and pays close attention to Emily’s bedroom. And then John Cavendish is arrested . . .

Poirot returned late that night.3 I did not see him until the following morning. He was beaming and greeted me with the utmost affection.

‘Ah, my friend – all is well – all will now march.’

Notebook 37 showing the beginning of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

‘Why,’ I exclaimed, ‘You don’t mean to say you have got—’

‘Yes, Hastings, yes – I have found the missing link.4 Hush . . .’

On Monday the hearing was resumed5 and Sir E.H.W. [Ernest Heavywether] opened the case for the defence. Never, he said, in the course of his experience had a murder charge rested on slighter evidence. Let them take the evidence against John Cavendish and sift it impartially.

What was the main thing against him? That the powdered strychnine had been found in his drawer. But that drawer was an unlocked one and he submitted that there was no evidence to show that it was the prisoner who placed it there. It was, in fact, a wicked and malicious effort on the part of some other person to bring the crime home to the prisoner. He went on to state that the Prosecution had been unable to prove to any degree that it was the prisoner who had ordered the beard from Messrs Parksons. As for the quarrel with his mother and his financial constraints – both had been most grossly exaggerated.

His learned friend had stated that if [the] prisoner had been an honest man he would have come forward at the inquest and explained that it was he and not his step-father who had been the participator in that quarrel. That view was based upon a misapprehension. The prisoner, on returning to the house in the evening, had been told at once6 that his mother had now had a violent dispute with her husband. Was it likely, was it probable, he asked the jury, that he should connect the two? It would never enter his head that anyone could ever mistake his voice for that of Mr. A[lfred] Inglethorp. As for the construction that [the] prisoner had destroyed a will – this mere idea was absurd. [The] prisoner had presented at the Bar and, being well versed in legal matters, knew that the will formerly made in his favour was revoked automatically. He had never heard a more ridiculous suggestion! He would, however, call evidence which would show who did destroy the will, and with what motive.

Finally, he would point out to the jury that there was evidence against other persons besides John Cavendish. He did not wish to accuse Mr. Lawrence Cavendish in any way; nevertheless, the evidence against him was quite as strong – if not stronger – than that against his brother.

Just at that point, a note was handed to him. As he read it, his eyes brightened, his burly figure seemed to swell and double its size.

‘Gentlemen of the jury,’ he said, and there was a new ring in his voice, ‘this has been a murder of peculiar cunning and complexity. I will first call the prisoner. He shall tell you his own story and I am sure you will agree with me that he cannot be guilty. Then I will call a Belgian gentleman, a very famous member of the Belgian police force in past years, who has interested himself in the case and who has important proofs that it was not the prisoner who committed this crime. I call the prisoner.’

John in the box acquitted himself well. His manner, quiet and direct, was all in his favour.7 At the end of his examination he paused and said, ‘I should like to say one thing. I utterly refute and disapprove of Sir Ernest Heavywether’s insinuation about my brother Lawrence. My brother, I am convinced, had no more to do with this crime than I had.’

Sir Ernest, remaining seated, noted with a sharp eye that John’s protest had made a favourable effect upon the jury. Mr Bunthorne cross-examined.8

‘You say that you never thought it possible that your quarrel with your mother was identical with the one spoken of at the inquest – is not that very surprising?’

‘No, I do not think so – I knew that my mother and Mr Inglethorp had quarrelled. It never occurred to me that they had mistaken my voice for his.’

‘Not even when the servant Dorcas repeated certain fragments of this conversation which you must have recognised?’

‘No, we were both angry and said many things in the heat of the moment which we did not really mean and which we did not recollect afterwards. I could not have told you which exact words I used.’

Mr Bunthorne sniffed incredulously.

‘About this note which you have produced so opportunely, is the handwriting not familiar to you?’

‘No.’

‘Do you not think it bears a marked resemblance to your own handwriting?’

‘No – I don’t think so.’

‘I put it to you that it is your own handwriting.’

‘No.’

‘I put it to you that, anxious to prove an alibi, you conceived the idea of a fictitious appointment and wrote this note to yourself in order to bear out your statement.’

‘No.’

‘I put it to you that at the time you claim to have been waiting about in Marldon Wood,9 you were really in Styles St Mary, in the chemist’s shop, buying strychnine in the name of Alfred Inglethorp.’

‘No – that is a lie.’

That completed Mr Bunthorne’s CE [cross examination]. He sat down and Sir Ernest, rising, announced that his next witness would be M. Hercule Poirot.

Poirot strutted into the witness box like a bantam cock.10 The little man was transformed; he was foppishly attired and his face beamed with self confidence and complacency. After a few preliminaries Sir Ernest asked: ‘Having been called in by Mr. Cavendish what was your first procedure?’

‘I examined Mrs Inglethorp’s bedroom and found certain . . .?’

‘Will you tell us what these were?’

‘Yes.’

With a flourish Poirot drew out his little notebook.

‘Voila,’ he announced, ‘There were in the room five points of importance.11 I discovered, amongst other things, a brown stain on the carpet near the window and a fragment of green material which was caught on the bolt of the communicating door between that room and the room adjoining, which was occupied by Miss Cynthia Paton.’12

‘What did you do with the fragment of green material?’

‘I handed it over to the police, who, however, did not consider it of importance.’

‘Do you agree?’

‘I disagree with that most utterly.’

‘You consider the fragment important?’

‘Of the first importance.’

‘But I believe,’ interposed the judge, ‘that no-one in the house had a green garment in their possession.’

‘I believe so, Mr Le Juge,’ agreed Poirot facing in his direction. ‘And so at first, I confess, that disconcerted me – until I hit upon the explanation.’

Everybody was listening eagerly.

‘What is your explanation?’

‘That fragment of green was torn from the sleeve of a member of the household.’

‘But no-one had a green dress.’

‘No, Mr Le Juge, this fragment is a fragment torn from a green land armlet.’

With a frown the judge turned to Sir Ernest.

‘Did anyone in that house wear an armlet?’

‘Yes, my lord. Mrs Cavendish, the prisoner’s wife.’

There was a sudden exclamation and the judge commented sharply that unless there was absolute silence he would have the court cleared. He then leaned forward to the witness.

‘Am I to understand that you allege Mrs Cavendish to have entered the room?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge.’

‘But the door was bolted on the inside.’

‘Pardon, Mr Le Juge, we have only one person’s word for that – that of Mrs Cavendish herself. You will remember that it was Mrs Cavendish who had tried that door and found it locked.’

‘Was not her door locked when you examined the room?’

‘Yes, but during the afternoon she would have had ample opportunity to draw the bolt.’13

‘But Mr Lawrence Cavendish has claimed that he saw it.’

There was a momentary hesitation on Poirot’s part before he replied.

‘Mr. Lawrence Cavendish was mistaken.’

Poirot continued calmly:

‘I found, on the floor, a large splash of candle grease, which upon questioning the servants, I found had not been there the day before. The presence of the candle grease on the floor, the fact that the door opened quite noiselessly (a proof that it had recently been oiled) and the fragment of the green armlet in the door led me at once to the conclusion that the room had been entered through that door and that Mrs Cavendish was the person who had done so. Moreover, at the inquest Mrs Cavendish declared that she had heard the fall of the table in her own room. I took an early opportunity of testing that statement by stationing my friend Mr Hastings14 in the left wing just outside Mrs Cavendish’s door. I myself, in company with the police, went to [the] deceased’s room and whilst there I, apparently accidentally, knocked over the table in question but found, as I had suspected, that [it made] no sound at all. This confirmed my view that Mrs Cavendish was not speaking the truth when she declared that she had been in her room at the time of the tragedy. In fact, I was more than ever convinced that, far from being in her own room, Mrs Cavendish was actually in the deceased’s room when the table fell. I found that no one had actually seen her leave her room. The first that anyone could tell me was that she was in Miss Paton’s room shaking her awake. Everyone presumed that she had come from her own room – but I can find no one who saw her do so.’

The judge was much interested. ‘I understand. Then your explanation is that it was Mrs Cavendish and not the prisoner who destroyed the will.’

Poirot shook his head.

‘No,’ he said quickly, ‘That was not the reason for Mrs Cavendish’s presence. There is only one person who could have destroyed the will.’

‘And that is?’

‘Mrs Inglethorp herself.’

‘What? The will she had made that very afternoon?’

‘Yes – it must have been her. Because by no other means can you account for the fact that on the hottest day of the year [Mrs Inglethorp] ordered a fire to be lighted in her room.’

The judge objected. ‘She was feeling ill . . .’

‘Mr Le Juge, the temperature that day was 86 in the shade. There was only one reason for which Mrs Inglethorp could want a fire – namely to destroy some document. You will remember that in consequence of the war economies practised at Styles, no waste paper was thrown away and that the kitchen fire was allowed to go out after lunch. There was, consequently, no means at hand for the destroying of bulky documents such as a will. This confirms to me at once that there was some paper which Mrs Inglethorp was anxious to destroy and it must necessarily be of a bulk which made it difficult to destroy by merely setting a match to it. The idea of a will had occurred to me before I set foot in the house, so papers burned in the grate did not surprise me. I did not, of course, at that time know that the will in question had only been made the previous afternoon and I will admit that when I learnt this fact, I fell into a grievous error. I deduced that Mrs Inglethorp’s determination to destroy this will came as a direct consequence of the quarrel and that consequently the quarrel took place, contrary to belief, after the making of the will.

‘When, however, I was forced to reluctantly abandon this hypothesis – since the various interviews were absolutely steady on the question of time – I was obliged to cast around for another. And I found it in the form of the letter which Dorcas describes her mistress as holding in her hand. Also you will notice the difference of attitude. At 3.30 Dorcas overhears her mistress saying angrily that “scandal will not deter her.” “You have brought it on yourself” were her words. But at 4.30, when Dorcas brings in the tea, although the actual words she used were almost the same, the meaning is quite different. Mrs Inglethorp is now in a clearly distressed condition. She is wondering what to do. She speaks with dread of the scandal and publicity. Her outlook is quite different. We can only explain this psychologically by presuming [that] her first sentiments applied to the scandal between John Cavendish and his wife and did not in any way touch herself – but that in the second case the scandal affected herself.

‘This, then, is the position: At 3.30 she quarrels with her son and threatens to denounce him to his wife who, although they neither of them realise it, overhears part of the conversation. At 4 o’clock, in consequence of a conversation at lunch time on the making of wills by marriage, Mrs Inglethorp makes a will in favour of her husband, witnessed by her gardener. At 4.30 Dorcas finds her mistress in a terrible state, a slip of paper in her hand. And she then orders the fire in her room to be lighted in order that she can destroy the will she only made half an hour ago. Later she writes to Mr Wells, her lawyer, asking him to call on her tomorrow as she has some important business to transact.

Now what occurred between 4 o’clock and 4.3015 to cause such a complete revolution of sentiments? As far as we know, she was quite alone during the time. Nobody entered or left the boudoir. What happened then? One can only guess but I have an idea that my guess is fairly correct.

‘Late in the evening Mrs Inglethorp asked Dorcas for some stamps and my thinking is this. Finding she had no stamps in her desk she went along to that of her husband which stood at the opposite corner. The desk was locked but one of the keys on her bunch fitted it. She accordingly opened the desk and searched for stamps – it was then she found the slip of paper which wreaked such havoc! On the other hand Mrs Cavendish believed that the slip of paper to which her mother [in-law] clung so tenaciously was a written proof of her husband’s infidelity. She demanded it. These were Mrs Inglethorp’s words in reply:

‘“No, [it is out of the] question.” We know that she was speaking the truth. Mrs Cavendish however, believed she was merely shielding her step-son. She is a very resolute woman and she was wildly jealous of her husband and she determined to get hold of that paper at all costs and made her plans accordingly. She had chanced to find the key of Mrs Inglethorp’s dispatch case which had been lost that morning. She had meant to return it but it had probably slipped her memory. Now, however, she deliberately retained it since she knew Mrs Inglethorp kept all important papers in that particular case. Therefore, rising about 4 o’clock she made her way through Miss Paton’s room, which she had previously unlocked on the other side.’

‘But Miss Paton would surely have been awakened by anyone passing through her room.’

‘Not if she were drugged.’

‘Drugged?’

‘Yes – for Miss Paton to have slept through all the turmoil in that next room was incredible. Two things were possible: either she was lying (which I did not believe) or her sleep was not a natural one. With this idea in view I examined all the coffee cups most carefully, taking a sample from each and analysing. But, to my disappointment, they yielded no result. Six persons had taken coffee and six cups were found. But I had been guilty of a very grave oversight. I had overlooked the fact that Dr Bauerstein had been there that night. That changed the face of the whole affair. Seven, not six people had taken coffee. There was, then, a cup missing. The servants would not observe this since it was the housemaid Annie who had taken the coffee tray in and she had brought in seven cups, unaware that Mr Inglethorp never took coffee. Dorcas who cleared them away found five cups and she suspected the sixth [of] being Mrs Inglethorp’s. One cup, then, had disappeared and it was Mademoiselle Cynthia’s, I knew, because she did not take sugar in her coffee, whereas all the others did and the cups I had found had all contained sugar. My attention was attracted by the maid Annie’s story about some “salt” on the cocoa tray which she took nightly into Mrs Inglethorp’s room. I accordingly took a sample of that cocoa and sent it to be analysed.’

‘But,’ objected the judge, ‘this has already been done by Dr Bauerstein – with a negative result – and the analysis reported no strychnine present.’

‘There was no strychnine present. The analysts were simply asked to report whether the contents showed if there were or were not strychnine present and they reported accordingly. But I had it tested for a narcotic.’

‘For a narcotic?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge. You will remember that Dr Bauerstein was unable to account for the delay before the symptoms manifested themselves. But a narcotic, taken with strychnine, will delay the symptoms some hours. Here is the analyst’s report proving beyond a doubt that a narcotic was present.’

The report was handed to the judge who read it with great interest and it was then passed on to the jury.

‘We congratulate you on your acumen. The case is becoming much clearer. The drugged cocoa, taken on top of the poisoned coffee, amply accounts for the delay which puzzled the doctor.’

‘Exactly, Mr Le Juge. Although you have made one little error; the coffee, to the best of my belief was not poisoned.’

‘What proof have you of that?’

‘None whatever. But I can prove this – that poisoned or not, Mrs Inglethorp never drank it.’

‘Explain yourself.’

‘You remember that I referred to a brown stain on the carpet near the window? It remained in my mind, that stain, for it was still damp. Something had been spilt there, therefore, not more than twelve hours ago. Moreover there was a distinct odour of coffee clinging to the nap of the carpet and I found there two long splinters of china. I later reconstructed what had happened perfectly, for, not two minutes before I had laid down my small despatch case on the little table by the window and, the top of the table being loose, the case had been toppled off onto the floor onto the exact spot where the stain was. This, then, was what had happened. Mrs Inglethorp, on coming up to bed had laid her untasted coffee down on the table – the table had tipped up and [precipitated] the coffee onto the floor – spilling it and smashing the cup. What had Mrs Inglethorp done? She had picked up the pieces and laid them on the table beside her bed and, feeling in need of a stimulant of some kind, had heated up her cocoa16 and drank it off before going to bed. Now, I was in a dilemma. The cocoa contained no strychnine. The coffee had not been drunk. Yet Mrs Inglethorp had been poisoned and the poison must have been administered sometime between the hours of seven and nine. But what else had Mrs Inglethorp taken which would have effectively masked the taste of the poison?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Yes – Mr Le Juge – she had taken her medicine.’

‘Her medicine – but . . .’

‘One moment – the medicine, by a [coincidence] already contained strychnine and had a bitter taste in consequence. The poison might have been introduced into the medicine. But I had my reasons for believing that it was done another way. I will recall to your memory that I also discovered a box which had at one time contained bromide powders. Also, if you will permit it, I will read out to you an extract – marked in pencil – out of a book on dispensing which I noticed at the dispensary of the Red Cross Hospital at Tadminster. The following is the extract . . .’17

‘But, surely a bromide was not prescribed with the tonic?’

‘No, Mr Le Juge. But you will recall that I mentioned an empty box of bromide powders. One of the powders introduced into the full bottle of medicine would effectively precipitate the strychnine and cause it to be taken in the last dose. You may observe that the “Shake the bottle” label always found on bottles containing poison has been removed. Now, the person who usually poured out the medicine was extremely careful to leave the sediment at the bottom undisturbed.’

A fresh buzz of excitement broke out and was sternly silenced by the judge.

‘I can produce a rather important piece of evidence in support of that contention, because on reviewing the case, I came to the conclusion18 that the murder had been intended to take place the night before. For in the natural course of events Mrs I[nglethorp] would have taken the last dose on the previous evening but, being in a hurry to see to the Fashion Fete she was arranging, she omitted to do so. The following day she went out to luncheon, so that she took the actual last dose 24 hours later than had been anticipated by the murderer. As a proof that it was expected the night before, I will mention that the bell in Mrs Inglethorp’s room was found cut on Monday evening, this being when Miss Paton was spending the night with friends. Consequently Mrs Inglethorp would be quite cut off from the rest of the house and would have been unable to arouse them, thereby making sure that medical aid would not reach her until too late.’

‘Ingenious theory – but have you no proof?’

Poirot smiled curiously.

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge – I have a proof. I admit that up to some hours ago, I merely knew what I have just said, without being able to prove it. But in the last few hours I have obtained a sure and certain proof, the missing link in the chain, a link in the murderer’s own hand, the one slip he made. You will remember the slip of paper held in Mrs Inglethorp’s hand? That slip of paper has been found. For on the morning of the tragedy the murderer entered the dead woman’s room and forced the lock of the despatch case. Its importance can be guessed at from the immense risks the murderer took. There was one risk he did not take – and that was the risk of keeping it on his own person – he had no time or opportunity to destroy it. There was only one thing left for him to do.’

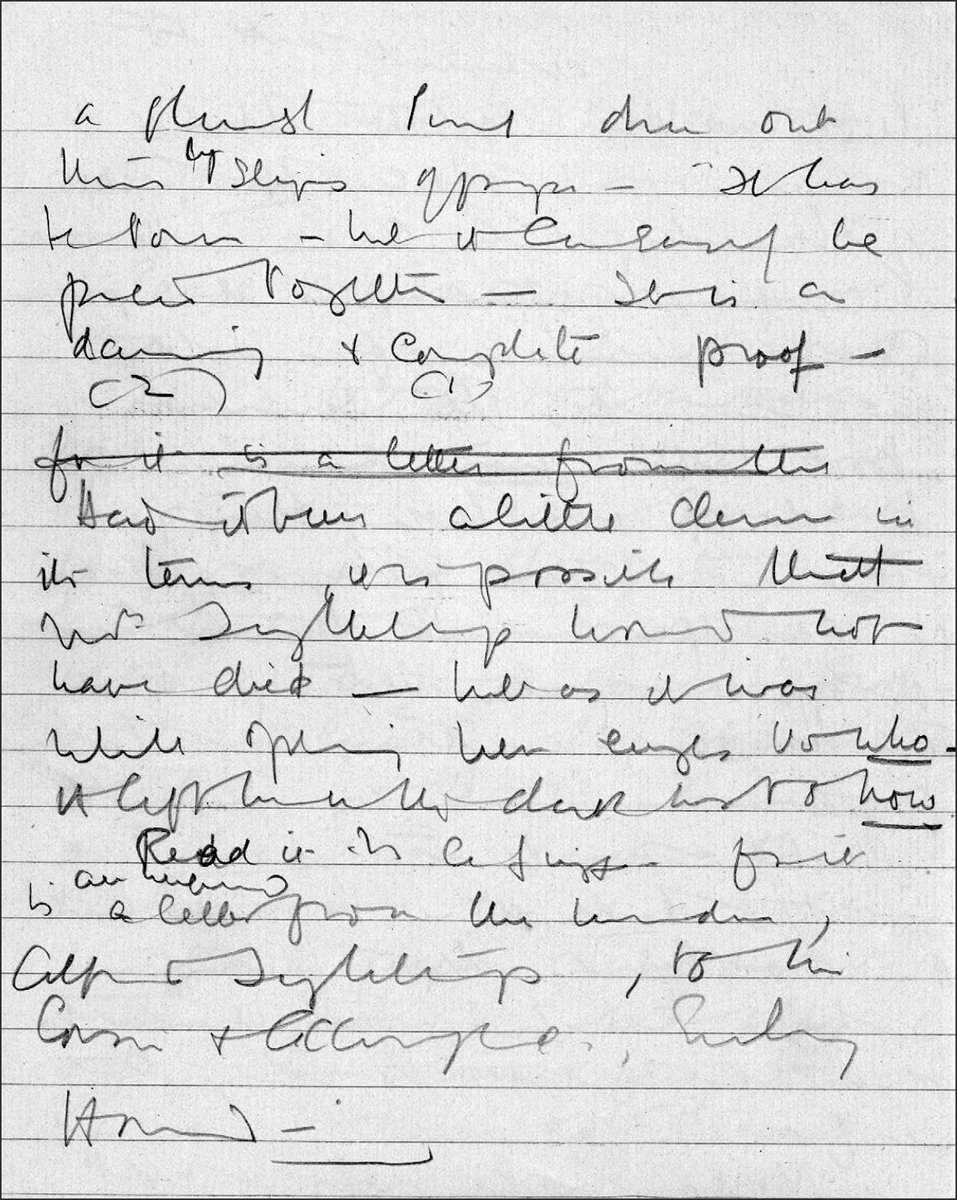

Notebook 37 showing the end of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles. See Footnote 19.

‘What was that?’

‘To hide it. He did hide it and so cleverly that, though I have searched for two months it is not until today that I found it. Voila, ici le prize.’

With a flourish Poirot drew out three long slips of paper.

‘It has been torn – but it can easily be pieced together. It is a complete and damning proof.19 Had it been a little clearer in its terms it is possible that Mrs Inglethorp would not have died. But as it was, while opening her eyes to who, it left her in the dark as to how. Read it, Mr Le Juge. For it is an unfinished letter from the murderer, Alfred Inglethorp, to his lover and accomplice, Evelyn Howard.’

And there, like Alfred Inglethorp’s pieced-together letter at the end of Chapter 12, Notebook 37 breaks off, despite the fact that the following pages are blank. We know from the published version that Alfred Inglethorp and Evelyn Howard are subsequently arrested for the murder, John and Mary Cavendish are reconciled, Cynthia and Lawrence announce their engagement, while Dr Bauerstein is shown to be more interested in spying than in poisoning. The book closes with Poirot’s hope that this investigation will not be his last with ‘mon ami’ Hastings.

The reviews on publication were as enthusiastic as the pre-publication reports for John Lane. The Times called it ‘a brilliant story’ and the Sunday Times found it ‘very well contrived’. The Daily News considered it ‘a skilful tale and a talented first book’, while the Evening News thought it ‘a wonderful triumph’ and described Christie as ‘a distinguished addition to the list of writers in this [genre]’. ‘Well written, well proportioned and full of surprises’ was the verdict of The British Weekly.

Poirot’s dramatic evidence in the course of the trial resembles a similar scene at the denouement of Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907), where the detective, Rouletabille, gives his remarkable and conclusive evidence from the witness box. Had John Lane but known it, in demanding the alteration to the denouement of the novel he unwittingly paved the way for a half century of drawing-room elucidations stage-managed by both Poirot and Miss Marple. And although this explanation, in both courtroom and drawing room, is essentially the same, the unlikelihood of a witness being allowed to give evidence in this manner is self-evident. In other ways also The Mysterious Affair at Styles presaged what was to become typical Christie territory – an extended family, a country house, a poisoning drama, a twisting plot, and a dramatic and unexpected final revelation.

It is not a very extended family, however. Of Mrs Inglethorp’s family, there is a husband, two stepsons, one daughter-in-law, a family friend, a companion and a visiting doctor; there is the usual domestic staff although none of them is ever a serious consideration as a suspect. In other words, there are only seven suspects, which makes the disclosure of a surprise murderer more difficult. This very limited circle makes Christie’s achievement in her first novel even more impressive. The usual clichéd view of Christie is that all of her novels are set in country houses and/or country villages. Statistically, this is inaccurate. Less than 30 (i.e. little over a third) of her titles are set in such surroundings, and the figure drops dramatically if you discount those set completely in a country house, as distinct from a village. But as Christie herself said, you have to set a book where people live.

Some ideas that feature in The Mysterious Affair at Styles would appear again throughout Christie’s career. The dying Emily Inglethorp calls out the name of her husband, ‘Alfred . . . Alfred’, before she finally succumbs. Is the use of his name an accusation, an invocation, a plea, a farewell; or is it entirely meaningless? Similar situations occur in several novels over the next 30 years. One novel, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, is built entirely around the dying words of the man found at the foot of the cliffs. In Death Comes as the End, the dying Satipy calls the name of the earlier victim, ‘Nofret’; as John Christow lies dying at the edge of the Angkatells’ swimming pool, in The Hollow, he calls out the name of his lover, ‘Henrietta.’ An extended version of the idea is found in A Murder is Announced when the last words of the soon-to-be-murdered Amy Murgatroyd, ‘she wasn’t there’, contain a vital clue and are subjected to close examination by Miss Marple. Both Murder in Mesopotamia – ‘the window’ – and Ordeal by Innocence – ‘the cup was empty’ and ‘the dove on the mast’ – give clues to the method of murder. And the agent Carmichael utters the enigmatic ‘Lucifer . . . Basrah’ before he expires in Victoria’s room in They Came to Baghdad.

The idea of a character looking over a shoulder and seeing someone or something significant makes its first appearance in Christie’s work when Lawrence looks horrified at something he notices in Mrs Inglethorp’s room on the night of her death. The alert reader should be able to tell what it is. This ploy is a Christie favourite and she enjoyed ringing the changes on the possible explanations. She predicated at least two novels – The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side and A Caribbean Mystery – almost entirely on this, and it makes noteworthy appearances in The Man in the Brown Suit, Appointment with Death and Death Comes as the End, as well as a handful of short stories.

In the 1930 stage play Black Coffee,20 the only original script to feature Hercule Poirot, the hiding-place of the papers containing the missing formula is the same as the one devised by Alfred Inglethorp. And in an exchange very reminiscent of a similar one in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, it is a chance remark by Hastings that leads Poirot to this realisation.

In common with many crime stories of the period there are two floor-plans and no less than three reproductions of handwriting. Each has a part to play in the eventual solution. And here also we see for the first time Poirot’s remedy for steadying his nerves and encouraging precision in thought: the building of card-houses. At crucial points in both Lord Edgware Dies and Three Act Tragedy he adopts a similar strategy, each time with equally triumphant results. The important argument overheard by Mary Cavendish through an open window in Chapter 6 foreshadows a similar and equally important case of eavesdropping in Five Little Pigs.

In his 1953 survey of detective fiction, Blood in their Ink, Sutherland Scott describes The Mysterious Affair at Styles as ‘one of the finest “firsts” ever written’. Countless Christie readers over almost a century would enthusiastically agree.

The Secret of Chimneys

12 June 1925

A shooting party weekend at the country house Chimneys conceals the presence of international diplomats negotiating lucrative oil concessions with the kingdom of Herzoslovakia. When a dead body is found, Superintendent Battle’s subsequent investigation uncovers international jewel thieves, impersonation and kidnapping as well as murder.

‘These were easy to write, not requiring too much plotting or planning.’ In her Autobiography, Agatha Christie makes only this fleeting reference to The Secret of Chimneys, first published in the summer of 1925 as the last of the six books she had contracted to produce for John Lane when they accepted The Mysterious Affair at Styles. In this ‘easy to write’ category she also included The Seven Dials Mystery, published in 1929, and, indeed, the later title features many of the same characters as the earlier.

The Secret of Chimneys is not a formal detective story but a light-hearted thriller, a form to which she returned throughout her writing career with The Man in the Brown Suit, The Seven Dials Mystery, Why Didn’t they ask Evans? and They Came to Baghdad. The Secret of Chimneys has all the ingredients of a good thriller of the period – missing jewels, a mysterious manuscript, compromising letters, oil concessions, a foreign throne, villains, heroes, and mysterious and beautiful women. It has distinct echoes of The Prisoner of Zenda, Anthony Hope’s immortal swashbuckling novel that Tuppence recalls with affection in Chapter 2 of Postern of Fate – ‘one’s first introduction, really, to the romantic novel. The romance of Prince Flavia. The King of Ruritania, Rudolph Rassendyll . . .’ Christie organised these classic elements into a labyrinthine plot and also managed to incorporate a whodunit element.

The story begins in Africa, a country Christie had recently visited on her world tour in the company of her husband Archie. The protagonist, the somewhat mysterious Anthony Cade, undertakes to deliver a package to an address in London. This seemingly straightforward mission proves difficult and dangerous and before he can complete it he meets the beautiful Virginia Revel, who also has a commission for him – to dispose of the inconveniently dead body of her blackmailer. This achieved, they meet again at Chimneys, the country estate of Lord Caterham and his daughter Lady Eileen ‘Bundle’ Brent. From this point on, we are in more ‘normal’ Christie territory, the country house with a group of temporarily isolated characters – and one of them a murderer.

That said, it must be admitted that a hefty suspension of disbelief is called for if some aspects of the plot are to be accepted. We are asked to believe that a young woman will pay a blackmailer a large sum of money (£40 in 1930 has the purchasing power today of roughly £1,500) for an indiscretion that she did not commit, just for the experience of being blackmailed (Chapter 7), and that two chapters later when the blackmailer is found inconveniently, and unconvincingly, dead in her sitting room, she asks the first person who turns up on her doorstep (literally) to dispose of the body, while she blithely goes away for the weekend. By its nature this type of thriller is light-hearted, but The Secret of Chimneys demands much indulgence on the part of the reader.

The hand of Christie the detective novelist is evident in elements of the narration. Throughout the book the reliability of Anthony Cade is constantly in doubt and as early as Chapter 1 he jokes with his tourist group (and, by extension, the reader) about his real name. This is taken as part of his general banter but, as events unfold, he is revealed to be speaking nothing less than the truth. For the rest of the book Christie makes vague statements about Cade and when we are given his thoughts they are, in retrospect, ambiguous.

Anthony looked up sharply.

‘Herzoslovakia?’ he said with a curious ring in his voice. [Chapter 1]

‘. . . was it likely that any of them would recognise him now if they were to meet him face to face?’ [Chapter 5]

‘No connexion with Prince Michael’s death, is there?’

His hand was quite steady. So were his eyes. [Chapter 18]

‘The part of Prince Nicholas of Herzoslovakia.’

The matchbox fell from Anthony’s hand, but his amazement was fully equalled by that of Battle. [Chapter 19]

‘I’m really a king in disguise, you know’ [Chapter 23]

And how many readers will wonder about the curious scene at the end of Chapter 16 when Anchoukoff, the manservant, tells him he ‘will serve him to the death’ and Anthony ponders on ‘the instincts these fellows have’? Anthony’s motives remain unclear until the final chapter, and the reader, despite the hints contained in the above quotations, is unlikely to divine his true identity and purpose.

There are references, unconscious or otherwise, to other Christie titles. The rueful comments in Chapter 5 when Anthony remarks, ‘I know all about publishers – they sit on manuscripts and hatch ’em like eggs. It will be at least a year before the thing is published,’ echo Christie’s own experiences with John Lane and the publication of The Mysterious Affair at Styles five years earlier. The ploy of leaving a dead body in a railway left-luggage office, adopted by Cade in Chapter 9, was used in the 1923 Poirot short story ‘The Adventure of the Clapham Cook’. Lord Caterham’s description of the finding of the body in Chapter 10 distinctly foreshadows a similar scene almost 20 years later in The Body in the Library when Colonel Bantry shares his unwelcome experience. And Virginia Revel’s throwaway comments about governesses and companions in Chapter 22 – ‘It’s awful but I never really look at them properly. Do you?’ – would become the basis of more than a few future Christie plots, among them Death in the Clouds, After the Funeral and Appointment with Death. The same chapter is called ‘The Red Signal’, also the title of a short story from The Hound of Death (see Chapter 3). Both this chapter and the short story share a common theme.

There are a dozen pages of notes in Notebook 65 for the novel, consisting mainly of a list of chapters and their possible content with no surprises or plot variations. But the other incarnation of The Secret of Chimneys makes for more interesting reading. Until recently this title was one of the few Christies not adapted for stage, screen or radio. Or so it was thought, until it emerged that the novel was actually, very early in her career, Christie’s first stage adaptation. The history of the play is, appropriately, mysterious. It was scheduled to appear at the Embassy Theatre in London in December 1931 but was replaced at the last moment by a play called Mary Broome, a twenty-year-old comedy by one Allan Monkhouse. The Embassy Theatre no longer exists and research has failed to discover a definitive reason for the last-minute cancellation and substitution. Almost a year before the proposed staging of Chimneys, Christie was writing from Ashfield in Torquay to her new husband, Max Mallowan, who was on an archaeological dig. Rather than clarifying the sequence of events, these letters make the cancellation of the play even more mystifying:

Tuesday [16 December 1930] Very exciting – I heard this morning an aged play of mine is going to be done at the Embassy Theatre for a fortnight with a chance of being given West End production by the Reandco [the production company]. Of course nothing may come of it but it’s exciting anyway. Shall have to go to town for a rehearsal or two end of November.

Dec. 23rd [1930] Chimneys is coming on here but nobody will say when. I fancy they want something in Act I altered and didn’t wish to do it themselves.

Dec. 31st [1930] If Chimneys is put on 23rd I shall stay for the first night. If it’s a week later I shan’t wait for it. I don’t want to miss Nineveh and I shall have seen rehearsals, I suppose.

A copy of the script was lodged with the Lord Chamberlain on 19 November 1931 and approved within the week, and rehearsals were under way. But it was discovered that, due possibly to an administrative oversight, the licence to produce the play had expired on 10 October 1931. Why it was not simply renewed in order to allow the play to proceed is not clear but it may have been due to financial considerations, because at the end of February 1932 the theatre closed, to reopen two months later under new management, the former company Reandco (Alec Rea and Co.) having sold its interest. But it must be admitted that this theory is speculative.

Whatever happened during the final preparations, Christie herself was clearly unaware of any problems and was as surprised and as puzzled as anyone at the outcome. The last two references to the play appear in letters written during her journey home, via the Orient Express, in late 1931 from visiting Max in Nineveh. The dating of the letters is tentative, for she was as slipshod about dating letters as she was about dating Notebooks.

[Mid November 1931] I am horribly disappointed. Just seen in the Times that Chimneys begins Dec. 1st so I shall just miss it. Really is disappointing

[Early December 1931] Am now at the Tokatlian [Hotel in Istanbul] and have looked at Times of Dec 7th. And ‘Mary Broome’ is at the Embassy!! So perhaps I shall see Chimneys after all? Or did it go off after a week?

And that was the last that was heard of Chimneys for over 70 years, until a copy of the manuscript appeared, equally mysteriously, on the desk of the Artistic Director of the Vertigo Theatre in Calgary, Canada. So, almost three-quarters of a century after its projected debut, the premiere of Chimneys took place on 11 October 2003. And in June 2006, UK audiences had the opportunity to see this ‘lost’ Agatha Christie play, when it was presented at the Pitlochry Theatre Festival.

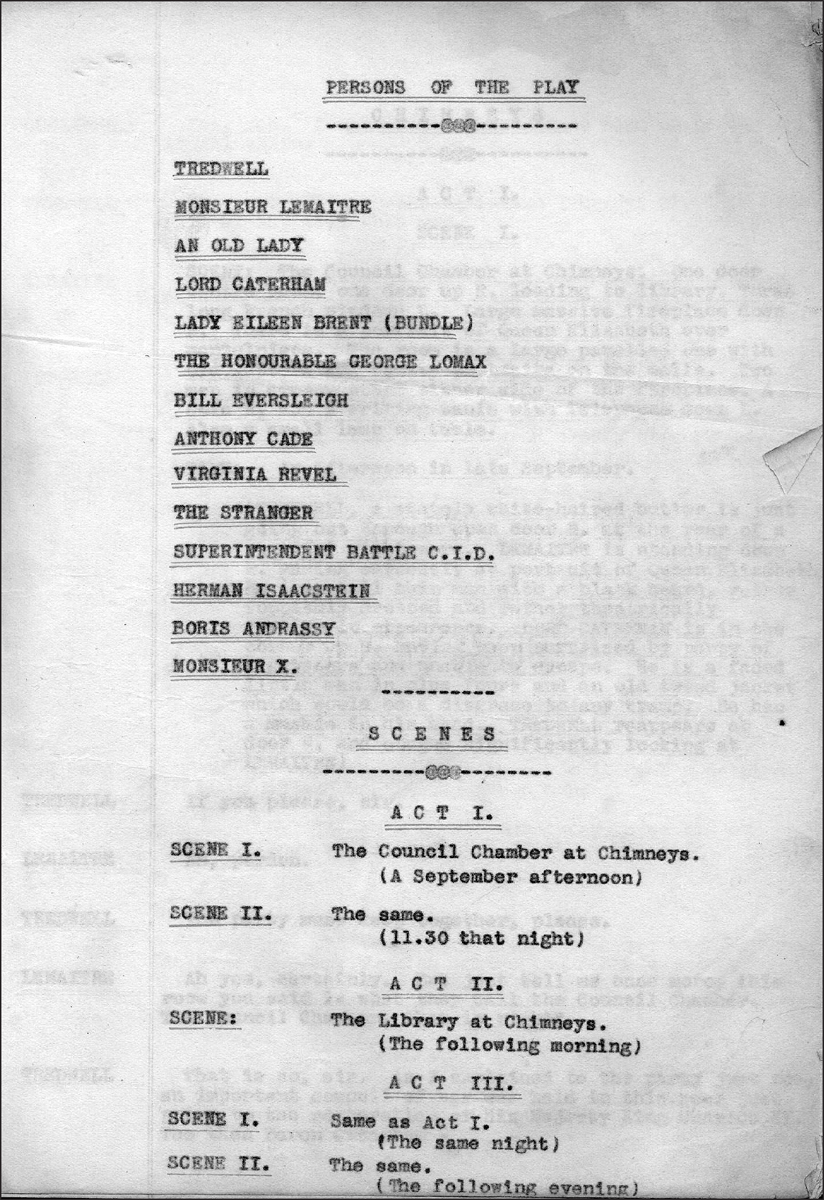

It is not known when exactly or, indeed, why Christie decided to adapt this novel for the stage. The use of the word ‘aged’ in the first letter quoted above would seem to indicate that it was undertaken long before interest was shown in staging it. The adaptation was probably done during late 1927/early 1928; a surviving typescript is dated July 1928. This would tally with the notes for the play; they are contained in the Notebook that has very brief, cryptic notes for some of the stories in The Thirteen Problems, the first of which appeared in December 1927. Nor does The Secret of Chimneys lend itself easily, or, it must be said, convincingly, to adaptation. If Christie decided in the late 1920s to dramatise one of her titles, one possible reason for choosing The Secret of Chimneys may have been her reluctance to put Poirot on the stage. She dropped him from four adaptations in later years – Murder on the Nile, Appointment with Death, The Hollow and Go Back for Murder (Five Little Pigs). The only play thus far to feature him was the original script, Black Coffee, staged the year before the proposed presentation of Chimneys. Yet, if she had wanted to adapt an earlier title, surely The Mysterious Affair at Styles or even The Murder on the Links would have been easier, set as they are largely in a single location and therefore requiring only one stage setting?

Perhaps with this in mind, the adaptation of The Secret of Chimneys is set entirely in Chimneys. This necessitated dropping large swathes of the novel (including the early scenes in Africa and the disposal, by Anthony, of Virginia’s blackmailer) or redrafting these scenes for delivery as speeches by various characters. This tends to make for a clumsy Act I, demanding much concentration from the audience as they are made aware of the back-story; but it is necessary in order to retain the plot. The second and third Acts are more smooth-running and, at times, quite sinister, with the stage in darkness and a figure with a torch making his way quietly across the set. There are also sly references, to be picked up by alert Christie aficionados, to ‘retiring and growing vegetable marrows’ and to the local town of Market Basing, a recurrent Christie location.

The solution propounded in the stage version is the earliest example of Christie altering her own earlier explanation. She was to do this throughout her career. On the stage she gave extra twists to And Then There Were None, Appointment with Death and Witness for the Prosecution; on the page, to ‘The Incident of the Dog’s Ball’/Dumb Witness, ‘Yellow Iris’/Sparkling Cyanide and ‘The Second Gong’/‘Dead Man’s Mirror’. In Chimneys she makes even more drastic alterations to the solution of the original; the character unmasked as the villain at the end of the novel does not even appear in the stage adaptation.

Some correspondence between Christie and Edmund Cork, her agent, in the summer of 1951 would seem to indicate that there were hopes of a revival, or to be strictly accurate, a debut of the play, due to the topicality of ‘recent developments in the oil business’; this is a reference to one of the elements of the plot, the question of oil concessions. But further developments in connection with a staging of the play, if any, remain unknown and it is clear that until Calgary in 2003 the script remained an ‘unknown’ Christie. The remote possibility that the script preceded the novel, which might have explained the unlikely choice of title for adaptation, is refuted by the reference in the opening pages of notes by the use of the phrase ‘Incidents likely to retain’.

There are amendments to the original novel in view of the fact that the entire play is set in Chimneys. As the play opens a weekend house party, arranged in order to conceal a more important international meeting, is about to begin, and by the opening of Act I, Scene ii the murder has been committed. And, in a major change from the novel, Anthony Cade and Virginia Revel are the ones to find the body, although they say nothing and allow the discovery to be made the following morning. In a scene very reminiscent of a similar one in Spider’s Web, Cade and Virginia examine the dead body and find the gun with Virginia’s name; in view of the danger in which this would place her, they agree to remain quiet about their discovery. In effect, Act II opens at Chapter 10 of the book and from there on both follow much the same plan.

A major divergence is the omission of the scenes involving the discovery and disposal, by Cade, of the blackmailer’s body. In fact, the entire blackmail scenario is substantially different. But whether written or staged, it is an unconvincing red herring and it could have been omitted entirely from the script without any loss. Other changes incorporated into the stage version include the fact that Virginia has no previous connection with Herzoslovakia, an aspect of the book that signally fails to convince. The secret passage from Chimneys to Wyvern Abbey is not mentioned, the character Hiram Fish has been dropped and the hiding place of the jewels is different from, and not as well clued as, that in the novel.

The Cast of Characters and Scenes of the Play from a 1928 script of Chimneys.

The notes for Chimneys are all contained in Notebook 67. It is a tiny, pocket-diary sized notebook and the handwriting is correspondingly small and frequently illegible. In addition to the very rough notes for some of The Thirteen Problems the Notebook contains sketches of some Mr Quin short stories, as well as notes for a dramatisation of the Quin story ‘The Dead Harlequin’. Overall, the notes for Chimneys do not differ greatly from the final version of the play, but substantial changes have been made from the original novel.

The first page reads:

People

Lord Caterham

Bundle

Lomax

Bill

Virginia

Tredwell

Antony

Prince Michael

Now what happens?

Incidents likely to retain – V[irginia] blackmailed

Idea of play

Crown jewels of Herzoslovakia stolen from assassinated King and Queen during house party at Chimneys – hidden there.

And twenty-five pages later she is amending her cast of characters:

Lord C

George

Bill

Tredwell

Battle

Inspector

Isaacstein

Bundle

Virginia

Antony

Lemaitre

Boris

The entire action of the play moves between the Library and the Council Chamber of Chimneys. The opening scene, which does not have an exact equivalent in the novel, introduces us to Lord Caterham, Bundle and George Lomax, the immensely discreet civil servant, arranging a top-level meeting that is to masquerade as a weekend shooting party. Chapter 16 of the novel has a brief reference to visitors being shown over the house and it is with such a brief scene that the play opens, as outlined below:

Act I Scene I – The Council Chamber

Lord C[aterham] in shabby clothes – Tredwell showing party over. ‘This is the . . . .’ A guest comes back for his hat tips Lord C. Bundle comes – ‘First bit [of honest money] ever earned by the Brents.’ She and Lord C – he complains of political party Lomax has dragged him into. Bundle says why does he do it? George arrives and B goes. Explanation etc. about Cade – the Memoirs – Streptiltich . . . the Press – the strain of public life etc. Mention of diamond – King Victor – stolen by the Queen, 3rd rate actress – more like a comic opera – she killed in revolution

Despite the crossing-out and amended heading of this extract, the following passage appears in the script as Act I, Scene ii. It corresponds to Chapter 9 of the novel, although there it takes place in Virginia’s house. I have broken up the extract and added punctuation to aid clarity.

Scene II – The Same (Evening)

Act II Scene I

That evening Antony arrives first – then V. He says about a poacher – shots – They do go to bed early – no light except in your window . . . – not this side of the house. Then she talks about the man – his queer manner – didn’t ask for money – wanted to find out. Then discovery of body – she screams. He stops her – takes her to chair.

‘It’s all right my dear, it’s all right.’

‘I’m quite all right.’

‘You marvellous creature – anyone else would have fainted.’

‘I want to look.’

He goes, coming back with revolver.

‘Yes – stay.’

He asks her to look.

‘You are marvellous’

‘Have you ever seen him before?’

‘Have I – Oh! Why, it’s the man – he’s different. He had horn-rimmed glasses – spoke broken English.’

‘This man wasn’t . . . He was educated at Eton and Oxford’

‘How do you know?’

‘Oh, I know all right. I’ve – I’ve seen his pictures in the newspapers’

‘Have you ever had a pistol?’

‘No’

‘It’s [an] automatic.’ Shows her.

‘It’s got my name on it.’

‘Did you tell anyone – anyone see come down here?

‘Go up to bed.’

‘Shouldn’t I shut the window after you?’

‘No – no . . .’

‘But . . .’

‘No tell tale footprints’

V goes. A. comes round – examines body. A little earth – he sweeps it up – wipes fingerprints from handles inside. Then goes out, looking at pistol.

Christie reorganises her earlier listing of acts and scenes, although the sequence is somewhat confused:

Act II Scene I – The Library

[Act II] Scene II – The Council Chamber

Act III

Act II Scene I – The same (evening)

Scene II – The Library (next morning)

Act III The Council Chamber (that evening)

[Scene] II The same – the following evening

[Act II] Scene II The library next morning

Bundle and her father (the police and doctor)

Then begins – splutters – I’ve got Battle. Battle comes in, asks for information. Scene much as before – plenty of rope – gets him to look at body next door – watches him through crack – Antony slips out unnoticed

And the third act is sketched twice, the second time in a more elaborate version:

Act III Scene I The following evening

Assembled in library – George and Battle read code letter – Richmond – they wait – struggle in darkness. Lights go up – Antony holding Lemaitre – always suspected this fellow – colleague from the Surete

Act III That evening Battle and George

Virginia, Lord C, Bundle go to bed. Lights out – George and Battle – the cipher – George 3 – man in armour. They [struggle] – door opens – the window – shadows. Suddenly outbreak of activity – they roll over and over – the man in armour clangs down. Suddenly door opens – Lord C. switches on light – others behind him. Battle in front of window – Antony on top of Lemaitre – ‘I’ve got you.’

As the above extract might suggest, The Secret of Chimneys is, both as novel and play, a hugely enjoyable but preposterous romp. Overall it is littered with loose ends, unlikely motivations and unconvincing characters. Characters drop notes with significant information; jewel thieves act with uncharacteristic homicidal responses; blackmail victims react with glee at a new ‘experience’ and bodies are disposed of with everyday nonchalance. And virtually nobody is who or what they seem. Why does Virginia not recognise Anthony if, as is reported in Chapters 15 and 24, she lived for two years in Herzoslovakia? Would someone really mistake a bundle of letters for the manuscript of a book? Would Battle accept Cade’s bona-fides so easily? It is difficult not to have a certain amount of sympathy with the pompous George Lomax and to sympathise deeply with the unfortunate Lord Caterham.

There are glimpses of the Christie to come in the final surprise revelation and the double-bluff with King Victor (in a novel about a disputed kingdom, why use this name for a character unconnected with the throne?), but her earlier thriller, The Man in the Brown Suit, and the later book with some of the Chimneys characters, The Seven Dials Mystery, are, if not more credible, at least far less incredible.

The Mystery of the Blue Train

29 March 1928

The elegant train is the setting for the murder of wealthy American Ruth Kettering. Fellow passenger Katherine Grey assists Hercule Poirot as he investigates the murder and the disappearance of the fabulous jewel, the Heart of Fire, among the wealthy inhabitants of the French Riviera.

The Mystery of the Blue Train was written at the lowest point in Christie’s life. In her Autobiography she writes, ‘Really, how that wretched book came to be written I don’t know.’ Following her disappearance and her subsequent separation from Archie Christie, she went to Tenerife with her daughter Rosalind and her secretary, Carlo Fisher, to finish the book she had already started. Rosalind constantly interrupted the writing of it, as she was a child not given to entertaining herself and demanded attention from her preoccupied mother.

The writing of this book also represented an important milestone in the career of Agatha Christie. She realised that she had advanced from amateur to professional status and now she had to write whether she wanted to or not. ‘I was driven desperately on by the desire, indeed the necessity, to write another book and make money.’ But ‘I had no joy in writing, no élan. I had worked out the plot – a conventional plot, partly adapted from one of my other stories . . . I have always hated The Mystery of the Blue Train but I got it written and sent it off to the publishers. It sold just as well as my last book had done. So I had to content myself with that – though I cannot say I have ever been proud of it.’ Most Christie fans would agree with her.

The short story to which she refers is ‘The Plymouth Express’, a minor entry in the Poirot canon, published in April 1923. It is a perfectly acceptable short story but it is debatable that it merited expansion into a novel. Frequently in the Notebooks she toys with the idea of expanding, inter alia, ‘The Third Floor Flat’ and ‘The Rajah’s Emerald’; why she opted for ‘The Plymouth Express’ remains a mystery. It is indeed a conventional plot and lacks both the ingenuity and glamour of her later train mystery, Murder on the Orient Express.

Extra complications in the shape of the history of the Heart of Fire are added in the novel and the inclusion of a new character, Katherine Grey, is significant. Katherine lives in St Mary Mead, although she does not know a certain Miss Jane Marple, who had made her detective debut some three months earlier in ‘The Tuesday Night Club’, the first of The Thirteen Problems. A quiet, determined, sensible young woman seeing the world for the first time, Katherine is a sympathetic character who captivates Poirot. And it is not fanciful to see her as a wish fulfilment for Christie herself.

The notes for The Mystery of the Blue Train are in Notebooks 1 and 54. Notebook 1 has a mere five pages but Notebook 54 has over 80, although the entries on each page are relatively short. They all reflect accurately the finished novel; no variations are considered and nor are there any ideas that did not make it into the published book, possibly because Christie was expanding a short story. For some reason the notes begin at Chapter 4 and then, 20 pages into Notebook 54, we find a listing of the earlier chapters, suggesting that the notes for those chapters had been destroyed.

I include a dozen pages from towards the end of Notebook 54. They contain Poirot’s explanation of the crimes, a passage so close to the published version in Chapter 35 that it merits reproduction in full, although the published version is more elaborate. Nowhere else in the plotting of her books is there anything else like this. Her flowing handwriting covers the pages, elucidating a complex plot with a minimum of deletion. Much of the following passage is almost exactly as Agatha Christie wrote it in Tenerife in 1927; it appears in the Notebook almost without punctuation, but I have added only enough to make it readable. The single most concentrated example of continuous text in the Notebooks, it is an impressive example of Christie’s fluency, clarity and readability – the factors that still play such an important part in her continuing popularity.

‘Explanations? Mais oui, I will give them to you. It began with 1 point – the disfigured face, usually a question of identity; but not this time. The murdered woman was undoubtedly Ruth Kettering and I put it aside.’

‘When did you first begin to suspect the maid?’

‘I did not for some time – one trifling [point] – the note case – her mistress not on such terms as would make it likely – it awakened a doubt. She had only been with her mistress two months yet I could not connect her to the crime since she had been left behind in Paris. But once having a doubt I began to question that statement – how did we know? By the evidence of your secretary, Major Knighton, a completely outside and impartial testimony, and by the dead woman’s own confession testimony to the conductor. I put that latter point aside for the moment because a very curious idea was growing up in my mind. Instead, I concentrated on the first point – at first sight it seemed conclusive but it led me to consider Major Knighton and at once certain points occurred to me. To begin with he, also, had only been with you for a period of 2 months and his initial was also K. Supposing – just supposing – that it was his notecase. If Ada Mason and he were working together and she recognised it, would she not act precisely as she had done? At first taken aback, she quickly fell in with him gave herself time to think and then suggested a plausible explanation that fell in with the idea of DK’s guilt. That was not the original idea – the Comte de la Roche was to be the stalking horse – but after I had left the hotel she came to you and said she was quite convinced on thinking it over that the man was DK – why the sudden certainty? Clearly because she had had time to consult with someone and had received instructions – who could have given her these instructions? Major Knighton. And then came another slight incident – Knighton happened to mention that he has been at Lady Clanraven’s when there had been a jewel robbery there. That might mean nothing or on the other hand it might mean a great deal. And so the links of the chain –’

‘But I don’t understand. Who was the man in the train?’

‘There was no man – don’t you see the cleverness of it all? Whose words have we for it, that there was a man. Only Ada Mason’s – and we believe in Ada Mason because of Knighton’s testimony.’

‘And what Ruth said . . .’

‘I am coming to that – yes – Mrs. Kettering’s own testimony. But Mrs Kettering’s testimony is that of a dead woman, who cannot come forward to dispute it.’

‘You mean the conductor lied?’

‘Not knowingly – the woman who spoke to him he believed in all good faith to be Mrs Kettering.’

‘Do you mean that it wasn’t her?’

‘I mean that the woman who spoke to the conductor was the maid, dressed in her mistress’s clothes – wearing her very distinctive clothes remember – more noticeable than the woman herself – the little red hat jammed down over the eyes – the long mink coat – the bunch of auburn curls each side of the face. Do you not know, however, that it is a commonplace nowadays how like one woman is to another in her street clothes.’

‘But he must have noticed the change?’

‘Not necessarily, he saw The maid handed him the tickets – he hadn’t seen the mistress until he came to make up the bed. That was the first time he had a good look at her and that was the reason for disfiguring the face – he would probably have noticed that the dead woman was not the same as the woman he had talked to. M. Grey would The dining room attendants might have noticed and M. Grey of course would have, but by ordering a dinner basket that danger was avoided.’

‘Then – where was Ruth?’

P[oirot] paused a minute and then said very quietly ‘Mrs Kettering’s dead body was rolled up in the rug on the floor in the adjoining compartment.’

‘My God!’

‘It is easily understood. Major Knighton was in Paris – on your business. He boarded the train somewhere on its way round the ceinture – he spoke perhaps of bringing some message from you – then he draws her attention to something out of the window slips the cord round her neck and pulls . . . .It is over in a minute. They roll up put the body in the adjoining compartment of which the door into the corridor is locked. Major Knighton hops off the train again – with the jewel case. Since the crime is not supposed to be committed until several hours later he is perfectly safe and his evidence and the supposed Mrs. Kettering’s words to the conductor will prove an alibi for her.

At the Gare de Lyon Ada Mason gets a dinner basket – then locks the door of her compartment – hurriedly changes into her mistress’s clothing – making up to resemble her and adjusting some false auburn curls – she is about the same height. Katherine Grey saw her standing looking out of her window later in the evening and would have been prepared to swear that she was still alive then. Before getting to Lyons, she arranges the body in the bunk, changes Her own into a man’s clothing and prepares to leave the train. It must have been then that When Derek Kettering enters his wife’s compartment the scene had been set and Ada Mason was in the other compartment waiting for the train to stop so as to leave the train unobserved – it is now drawn into Lyons – the conductor swings himself down – she follows, unobtrusively however, to proceed by slouching inelegantly along as though just taking the air but in reality she crosses over and takes the first train back to Paris where she establishes herself at the Ritz. Her name has been entered registered as booking a room the night before by one of Knighton’s female accomplices; she has only to wait for Mr. Van Aldin’s arrival. The jewels are in Knighton’s possession – not hers – and he disposes of them to Mr Papapolous21 in Nice as arranged beforehand, entrusting them to her care only at the last minute to deliver to the Greek. All the same she made one little slip . . .’

‘When did you first connect Knighton with the Marquis?’

‘I had a hint from Mr Papapolous and I collected certain information from Scotland Yard – I applied it to Knighton and it fitted. He spoke French like a Frenchman; he had been in America and France and England at roughly the same times as the Marquis was operating. He had been last heard of doing jewel robberies in Switzerland and it was in Switzerland that you first met Major K. The Marquis was famous for his charm of manner [which he used] to induce you to offer him the post of secretary. It was at that time that rumours were going round about your purchase of the rubies – the Marquis meant to have these rubies. In seeing that you had given them to your daughter he installed his accomplice as her maid. It was a wonderful plan yet like great men he has his weakness – he fell genuinely in love with Miss Grey. It was that which made him so desirous of shifting the crime from Mr Comte de la Roche to Derek Kettering when the opportunity presented itself. And Miss Grey suspected the truth. She is not a fanciful woman by any means but she declares that she distinctly felt your daughter’s presence beside her one day at the Casino; she says she was convinced that the dead woman was trying to tell her something. Knighton had just left her – and it was gradually [borne in on her] what Mrs Kettering had been trying to convey to her – that Knighton was the man who had murdered her. The idea seemed so fantastic at the time that Miss Grey spoke of it to no one. But she acted on the assumption that it was true – she did not discourage Knighton’s advances, and she pretended to him that she believed in Derek Kettering’s guilt. . . .

‘There was one thing that was a shocking blow. Major Knighton had a distinct limp, the result of a wound – the Marquis had no such limp – that was a stumbling block. Then Miss Tamplin mentioned one day that it had been a great surprise to the doctors that he should limp – that suggested camouflage. When I was in London I went to the surgeon who had looked after been in charge at Lady Tamplin’s Hospital and I got various technical details from him which confirmed my assumption. Then I met Miss Grey and found that she had been working towards the same end as myself. She had the cuttings to add – one a cutting of a jewel robbery at Lady Tamplin’s Hospital, another link in the chain of probability and also that when she was out walking with Major Knighton at St. Mary Mead, he was so much off his guard that he forgot to limp – it was only a momentary lapse but she noted it. She had suspicion that I was on the same track when I wrote to her from the Ritz. I had some trouble in my inquiries there but in the end I got what I wanted – evidence that Ada Mason actually arrived on the morning after the crime.’