Chapter 4

The Second Decade 1930–1939

‘The funny thing is that I have little memory of the books I wrote just after my marriage. ’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

Black Coffee • ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’ • Death in the Clouds • Death on the Nile • Evil under the Sun • Endless Night • Hercule Poirot’s Christmas • Lord Edgware Dies • The Murder at the Vicarage • The Mysterious Affair at Styles • ‘The Second Gong’ • Three Act Tragedy • Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?

The years 1930 to 1939 were undoubtedly Agatha Christie’s Golden Age, in terms of ingenuity, productivity and diversity. In 1930 she published the first Miss Marple novel, The Murder at the Vicarage, and the first Mary Westmacott, Giant’s Bread. By the end of the decade she had produced a further 16 full-length novels and six short story/novella collections (seven if the US-only The Regatta Mystery in 1939 is included). Many of her classic titles appeared in this decade. She experimented with the detective story form in And Then There Were None (1939), she broke the rules in Murder on the Orient Express (1934), she pioneered an early example of the serial killer in The A.B.C. Murders (1936) and wrote a light-hearted thriller with Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? (1934). Reflecting her own love of travel, she sent Poirot abroad in Murder in Mesopotamia (1936), Death on the Nile (1937) and Appointment with Death (1938), for the type of detective experience not shared by most of his literary crime-solving contemporaries.

As well as an impressive output of detective novels, she also published short stories – crime fantasy with The Mysterious Mr Quin (1930), the supernatural in The Hound of Death (1933), a mixture of crime, romance and light-hearted adventure in The Listerdale Mystery and Parker Pyne Investigates (both 1934); and mastered the difficult novella form in Murder in the Mews (1937). Despite the first appearance of Miss Marple in a full-length book and the publication of some of Poirot’s best cases, she also published non-series titles – The Sittaford Mystery (1931) and Murder is Easy (1939). In addition, she wrote the scripts for Black Coffee (1930), her only original Poirot play, and Akhnaton (written 1937), a historical drama set in ancient Egypt. She contributed to the round-robin detective stories of the Detection Club, Behind the Screen in 1930 and The Floating Admiral and The Scoop in 1931; and she wrote her first radio play, Yellow Iris (1937).

She would never again – perhaps not surprisingly – equal this productivity; the second half of the following decade saw her slow down to a mere one title a year. But the truly astonishing aspect of this output is not just the volume but also the consistency. None of the titles produced in these years fall below the level of excellent. All of them display her talents – ingenuity and readability, intricacy and simplicity – at the height of their powers and many are now recognised classics of the genre, representing a standard which other crime writers strove to match.

Her work was in demand for the lucrative magazine market in the UK and North America and for translation throughout Europe. She was one of the first writers to be chosen, in 1935, for publication in the new Penguin paperbacks; and her hardback sales for each new title entered the five-figure category. From Three Act Tragedy (1935) onwards her first-year sales never fell below 10,000. Film versions of her work – Alibi (based on The Murder of Roger Ackroyd) and Black Coffee, both in 1931, and Lord Edgware Dies in 1934 – were released, although all three featured a seriously miscast Austin Trevor, a six foot tall Irishman, in the role of Poirot; and Love from a Stranger, adapted from the short story ‘Philomel Cottage’, appeared in 1937 with Joan Hickson in a small role. Black Coffee and Love from a Stranger had been produced as stage plays earlier in the decade; and Chimneys, her own stage adaptation of her 1925 novel, was scheduled to appear in 1931 but was cancelled for reasons still unknown. The first Christie, and Poirot, on television came in June 1937 with the broadcast of Wasp’s Nest.

It is entirely possible that Christie’s happy personal life was, at least in part, responsible for this productive professional life. In September 1930 she had married Max Mallowan, thus ending the profoundly unhappy period of her life which began with the death of her mother in 1926 and culminated in her divorce from Archie Christie in 1928. Secure in a stable marriage, with a happy and healthy daughter, and spending some months of every year cheerfully working on an archaeological dig with her husband, she produced new books with enviable ease. And to judge from the evidence of the Notebooks, plot ideas for future books were not in short supply. The early 1930s coincide with the most indecipherable pages of the Notebooks, when her handwriting could hardly keep pace with her ingenuity. By the mid 1930s, reading the latest Agatha Christie had become not just a national but an international pastime.

The Murder at the Vicarage

13 October 1930

When unpopular churchwarden Colonel Protheroe is found shot in the vicar’s study in St Mary Mead, the vicar’s neighbour identifies seven potential murderers. Two confessions, an attempted suicide and a robbery confuse the issue but Miss Marple understands everything when she realises the significance of the potted palm.

The Murder at the Vicarage was the first Agatha Christie title issued under the new Crime Club imprint, and the first book-length investigation for Miss Marple. It appeared in serial form in the USA three months before its UK publication, leading to the conclusion that the bulk of the novel was completed during 1929. Disappointingly, Christie writes in her Autobiography that ‘I cannot remember where, when or how I wrote it, why I came to write it or even what suggested to me that I should select a new character – Miss Marple.’ She goes on to explain that the enjoyment she got from the creation of the Caroline Sheppard character in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was a factor in the decision to re-create an ‘acidulated spinster, full of curiosity, knowing everything, hearing everything; the complete detective service in the home’. The character of Miss Marple in The Murder at the Vicarage is considerably different from the Miss Marple of her next case 12 years later, The Body in the Library.

Jane Marple made her first appearance in print in a series of six short stories published between December 1927 and May 1928 in the Royal Magazine, beginning with ‘The Tuesday Night Club’. A further six stories were published between December 1929 and May 1930 in The Story-Teller and all 12 were published, with the addition of ‘Death by Drowning’, as The Thirteen Problems in June 1932. In the first story Miss Marple sits in her house in St Mary Mead, dressed completely in black – black brocade dress, black mittens and black lace cap – in the big grandfather chair, knitting and listening and solving crimes that have baffled the police. She is described as ‘smiling gently’ and having ‘benignant and kindly’ blue eyes. But the first description we receive of her, from the vicar’s wife, Griselda, in The Murder at the Vicarage is ‘that terrible Miss Marple . . . the worst cat in the village’. The vicar himself, while describing her as ‘a white-haired old lady with a gentle, appealing manner’, also concedes that ‘she is much more dangerous’ than her fellow parishioner the gushing Miss Wetherby. He captures the essence of Miss Marple when he states in Chapter 4 that ‘There’s no detective in England equal to a spinster lady of uncertain age with plenty of time on her hands.’ By 1942 and The Body in the Library, Miss Marple has cast off, temporarily at least, both St Mary Mead and her black lace mittens to accompany Dolly Bantry to the Majestic Hotel in Danemouth to solve the murder of Ruby Keene. And thereby to join the company of the Great Detectives.

The Murder at the Vicarage has its origins in the Messrs Satterthwaite and Quin short story ‘The Love Detectives’, published in December 1926 in The Storyteller magazine. Here two adulterous lovers commit murder and then confess separately, confident in the knowledge that if they make the ‘confessions’ incredible enough (they each claim to have used different and incorrect weapons), neither of them will be believed. In both short story and novel the victim is the husband, and the killers are his wife and her lover. Significantly, in each case a stopped clock causes confusion as to the time of death. The novel adapts the motive, the means and the device of false confessions, adds extra suspects and replaces the duo of Satterthwaite and Quin with Miss Marple; but they are, essentially, the same story.

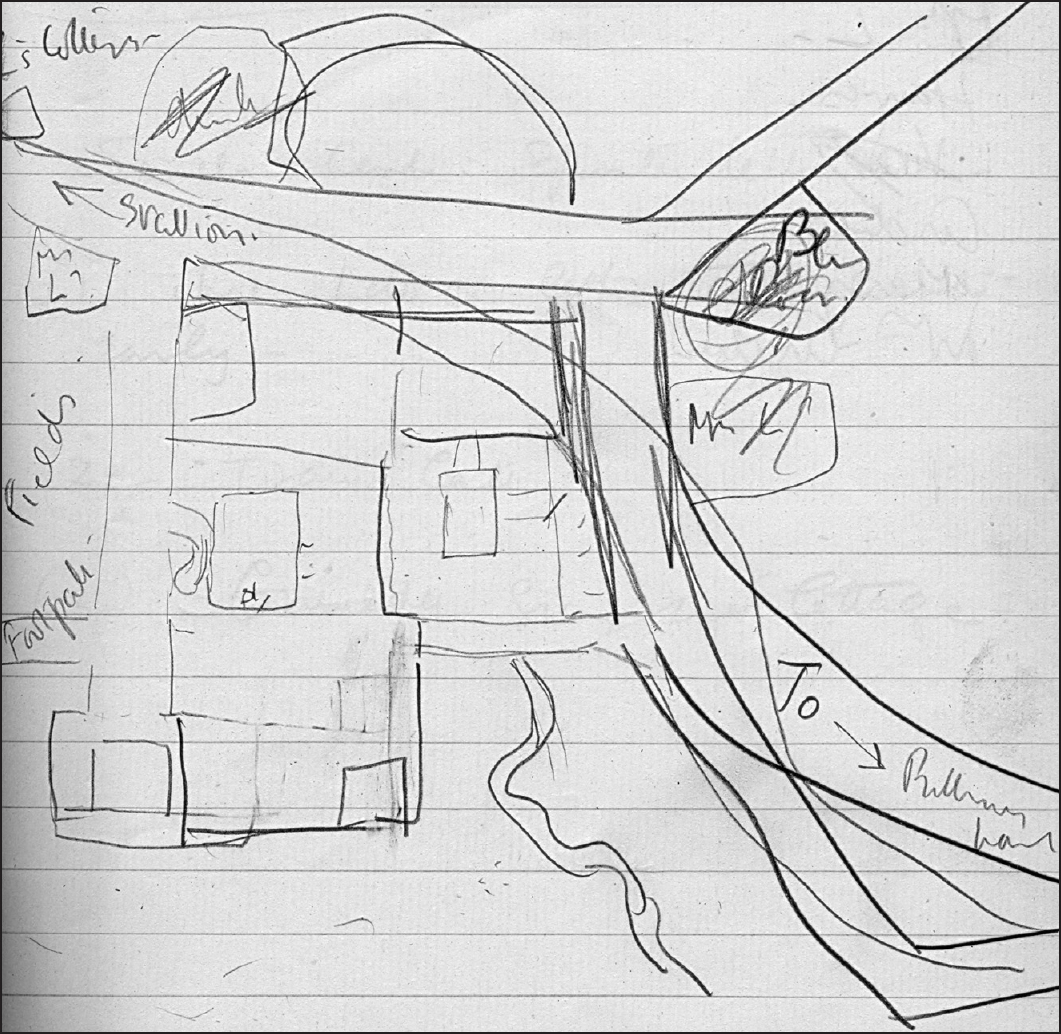

The notes for The Murder at the Vicarage are all contained in Notebook 33 and consist of 70 very organised pages that closely follow the progress of the novel. For the early chapters the chapter number is included; thereafter the remainder of the notes follow the novel in chronological order. There is little in the notebook that is not included in the published version. Two maps of St Mary Mead are included and the rest of Notebook 33 contains the draft for Three Act Tragedy.

From Notebook 33 Christie’s own sketch of St Mary Mead for The Murder at the Vicarage showing most of the locations that appear in that novel.

For some reason, the notes for The Murder at the Vicarage begin at Chapter 3; there is no record anywhere of the first two chapters. The extracts below have been edited for clarity.

Chapter III

Griselda and Vicar – Vicar meets Mrs L[estrange] at Church – shows her round. Studio – he goes to it to see picture – Anne and Lawrence. Anne comes to him in Study – taps on window

Chapter IV

Dinner that night – Lawrence there – Dennis – afterwards Lawrence with vicar. Dennis comes in after Lawrence has gone – wants to tell things. Says ‘What a rotten thing gossip is.’ Where does Mrs Lestrange go to at night.

Chapter V

Vicar called away – returns and discovers body.

Although the next extract is labelled ‘Chapter VII’ in the Notebook, it appears in the published novel as Chapter 6. From here on the Notebook does not specify chapter headings; I have added the actual chapter numbers to preserve the chronology:

Chapter VII [actually Chapter 6]

Inspector shuts up room and window and leaves word no-one is to go in. Learns from Mary next morning Mr Redding has been arrested – Griselda says ‘What’ – incredulous – couldn’t be Lawrence. What earthly motive. Vicar does not want to say about Anne. Entrance of Miss Marple – very terrible business – discusses it with them. Of course one knows who one thinks – one might be wrong. They tell her L arrested. She is suspicious – he has confessed. Oh! Then – I see I was wrong – I must have been wrong. Explain about clock – Griselda says again he knew. Miss M pounces on note – ‘Yes that is curious.’ Mary says Col. Melchett.

[Chapter 7]

A sad business – young Redding came in to the police station, threw down the pistol, a Mauser 25, and gave himself up. Declined to give motive. One thing I am amazed – the shot not heard. Vicar explains where kitchen is – still, I feel it would have been heard – silencer. They go to Haydock. They tell him Redding has confessed – Haydock looks relieved – that saves us all a lot of anxiety. Say 6.30 not later than that – the body was cold, man. Redding couldn’t have shot him then. He looked worried – but if the man says so he’s lying. But why on earth should he lie?

[Chapter 8]

The clock – what about the clock – it stopped at 6.22. Oh! I put it back. Note [from Anne] to Vicar. ‘Please – please – come up to see me. I have got to tell someone.’ Hands it to Col Melchett – they go up – Slack, Col and vicar. They go up. Anne – Want to ask you a few questions – she looks at him. Have you told them? I shook my head. I’ve been such a coward – such a coward – I shot my husband – I was desperate. Something came over me – I went up behind him and fired. The pistol? It – it was my husband’s – I took it out of a drawer. Did you see anyone? No – Oh! yes – Miss Marple.

[Chapter 9]

They go to see Miss Marple. They ask her. Yes – I saw Mrs Protheroe at about a quarter past six. No – not flustered at all. She said she had come to walk home with her husband. Lawrence came from wood path and joined her. They went into the studio – then left and walked off that way. She must have taken the pistol with her. Miss M says no pistol with her. Slack says concealed on her person – Miss M says ‘quite impossible.’

[Chapter 10]

Vicar goes home – Miss Cram with Griselda – about Guides – really curious – she goes. Vicar and Mary – about shot. What time – she is amazed. Griselda says about Archer the poacher. Colonel and Slack arrive. They go into study.

[Chapter 11]

Miss Marple with Griselda – Miss M says it reminds her of things etc. etc. – the washerwoman and the other woman – hate. I wish you would tell me the 7 [suspects]. She shook her head. The note – the curious point about it.

[Chapter 12]

They go to interview Lawrence. He tells – arrived there to say I couldn’t leave after all – found him dead. Pistol – it was mine – I picked it up and rushed. I felt demented. You were sure it was Anne? He bowed his head. I thought that after we had parted that afternoon she had gone back and shot him. No, he had never touched the clock. Mrs P, we know you didn’t do it. Now – will you tell me what you did? She does. If anyone else confesses to the murder, I will go mad.

[Chapter 13]

Miss Hartnell [actually changed to Mrs Price-Ridley] indignant complaint about being rung up – a degenerate voice. It threatened me – asked about shot. Yes, I did hear something down in the wood – just one odd shot – but I didn’t notice it particularly

[Chapter 14]

Haydock says about Hawes – Encephalitis lethargica. Mention of Dennis age by Haydock.

Although the novel is narrated by the vicar, it is not until Chapter 15 that ‘I’, the narrator, appears. Note the fluctuation thereafter between first and third person narrative:

Note from Mrs. Lestrange – I go there. Has hardly greeted her before the Inspector arrives – she asks vicar to stay – questions. She refuses information.

[Chapter 16]

It was after tea time that I put into execution a plan of my own – whoever committed the murder etc. Goes into wood – meets Lawrence with large stone in his hands. He explains – for Miss Marple’s rock garden

[Chapter 18]

Inquest that morning [afternoon] – Vicar and doctor and Lawrence give evidence. Anne Protheroe – her husband in usual spirits – Mrs Lestrange – Dr Haydock gave medical certificate. Murder by person or persons unknown.

[Chapter 19]

Then drops into Lawrence’s cottage. He describes how he got on at Old Hall – a tweenie overheard something – wasn’t going to tell the police.

[Chapter 20]

Vicar goes home – finds Lettice has been there – Mary very angry – has come home and found her searching in study – yellow hat.

[Chapter 21]

After dinner – Raymond West – the crime – Mr Stone. Raymond says it wasn’t him. Great excitement – tell the police. Another peculiar thing – I told him about the suit case.

[Chapter 22]

Letter from Anne – Vicar goes up to see her – a very extraordinary occurrence. Takes me to attic – the picture with the slashed face. Who is it? The initials E.P. on trunk.

[Chapter 23]

Vicar on way back knows police are searching barrow – his sudden brain wave – finds suitcase – takes it to police station – old silver.

[Chapter 24]

Vicar goes home – Hawes there – says will vicar preach – reference to headache powder. Notes 3 by hand – one in box – anonymous one.

[Chapter 25]

Mrs Price Ridley – her maid, standing at gate, saw something or heard somebody sneeze. Or a tennis racquet in a hedge – on the way back along footpath.

Near the end of the notes is a draft of the schedule that appears in Chapter 26. This also tallies in general with the published version. Minor details – the date of the month and a difference of minutes in some of the timetable – are, however, changed, as can be seen from a comparison with the published version.

Occurrences in connection with the death of Colonel Protheroe

To be explained [and] arranged in chronological order

Wednesday Thursday – 20th

11.30 Col. Protheroe alters time of appointment to 6.15 – easily overheard

12.30 Mrs Archer says pistol was still at Lawrence Redding’s cottage – but has previously said she didn’t know

5.30 Fake call put through to me from East Lodge – by whom?

5.30 Col and Mrs P leave Old Hall in car and drive to village

6.14 Col. P arrives at my house Vicarage and is shown into study by maid Mary

6.20 Anne Protheroe comes to study window – Col P not visible (writing at desk)

6.23 L and A go into studio

6.30–6.35 The shot

6.30–6.35 Call put through from LR’s cottage to Mrs PR

6.45 L.R. visits vicarage finds body

6.50 I find body

The attempted murder of Hawes and the text of the ambiguously worded but apparently incriminating letter of Chapter 29 are sketched in the closing stages of the notes, which end abruptly with the revelation of the guilty names:

[Chapters 27/28]

The call – I – I want to confess. Can’t get number. Goes there – finds letter on table.

[Chapter 29]

Dear Clement

It is a peculiarly unpleasant thing I have to say – after all I think I prefer writing it. It concerns the recent peculations. I am sorry to say that I have satisfied myself beyond any possible doubt of the identity of the culprit. Painful as it is for me to have to accuse an ordained priest of the Church . . .

The Notebook has no mention of Miss Marple’s explanation, although her casual mention of the names of the guilty is reflected in the book:

Melchett arrives – Hawes ill – they send for Haydock – overdose of sulphanol.

Miss M says Yes – that’s what he wants you to think – the confession of the letter – the overdose – that he took himself. It all fits in – but it’s wrong. It’s what the murderer wants you to think.

The murderer?

Yes – or perhaps I’d better say Mr Lawrence Redding

[Chapter 30]

They stare at her.

Of course Mr R is quite a clever young man. He would, as I have said all along, shoot anyone and come away looking distraught.

But he couldn’t have shot Col Protheroe.

No – but she could.

Who?

Mrs Protheroe.

As the first Marple novel, the place of The Murder at the Vicarage in crime fiction history is an important one. Miss Marple is the most famous, and arguably the most able, of the elderly female detectives. She was not the first; that honour goes to Miss Amelia Butterworth, who solved her first case in The Affair Next Door in 1897. Created by Anna Katherine Green, sometimes called the Mother of the Detective Story, Amelia’s career was predicated on a combination of leisure and inquisitiveness, as distinct from the professional female whose motivation was mainly economic. Other well-known contemporary female sleuths included spinster schoolteacher Hildegarde Withers, the creation of Stuart Palmer; mystery writer Susan Dare, the creation of M.G. Eberhart; professional psychologist Mrs Bradley, the creation of Gladys Mitchell; and private enquiry agent Miss Maud Silver, the creation of Patricia Wentworth. All these were contemporaries of Miss Marple, although only the heroine of St Mary Mead can be classified as a complete amateur.

The Murder at the Vicarage is a typical village murder mystery of the sort forever linked with the name of Agatha Christie; although, with ten books already published, it was only the second such novel she had produced, the other being The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Its central ploy – the seemingly impregnable alibis of a pair of murderous adulterers – was one to which Christie would return throughout her career. It had already featured in The Mysterious Affair at Styles; Death on the Nile, Evil under the Sun and Endless Night are other prime examples.

The Sittaford Mystery

7 September 1931

During a séance at Sittaford House the death of Captain Trevelyan is predicted. The worst fears of his friend Major Burnaby are realised when he finds the Captain’s body, murdered in his own home, six miles away. Inspector Narracott investigates with the unsought help of Emily Trefusis, whose fiancé has been arrested.

Despite the full-length debut of Miss Marple in The Murder at the Vicarage the previous year and the absence of Hercule Poirot since The Mystery of the Blue Train in 1928, Christie submitted a non-series novel to The Crime Club in 1931. The Sittaford Mystery had a six-part serialisation in the USA, as Murder at Hazelmoor, six months prior to its UK release.

The small bungalows, each with a quarter-acre of ground, described in Chapter 1 of The Sittaford Mystery owe their inspiration, according to an early draft of Christie’s Autobiography, to the granite bungalow in Throwleigh, Dartmoor purchased for £800 by Christie and her sister Madge for their brother Monty on his return from Africa in 1923. The background of Dartmoor, and the sub-plot of the escaped convict, inevitably recalls Arthur Conan Doyle and his Sherlock Holmes novel The Hound of the Baskervilles (1896), which uses the same evocative and atmospheric setting as well as a similar sub-plot. Conan Doyle himself is referenced in Chapter 11 when Charles Enderby plans to write to him for an opinion on séances; this is a reference to Conan Doyle’s enthusiasm for spiritualism, an interest that dominated the last years of his life. Despite the passing reference in Chapter 7 to Trevelyan’s will, dated 13 August 1926, having been written ‘five or six years ago’, the mention of Conan Doyle indicates that The Sittaford Mystery was written, at the latest, in early 1930, as Conan Doyle died in July of that year.

As a plot device, the supernatural appeared spasmodically throughout the works of Agatha Christie. Two years after The Sittaford Mystery Christie published The Hound of Death, a collection of short stories, most of them published years earlier in various magazines, whose overall theme is the supernatural. It includes stories about a psychic in ‘The Hound of Death’, second sight in ‘The Gipsy’, a ghost in ‘The Lamp’, possession in ‘The Strange Case of Sir Arthur [sometimes Andrew] Carmichael’; and in ‘The Last Séance’ and ‘The Red Signal’ a séance, also the main plot device of The Sittaford Mystery. In the later novels Dumb Witness and The Pale Horse, the supernatural plays a part; and in Taken at the Flood it is her psychic ‘gift’ that directs Katherine Cloade to approach Hercule Poirot. However, in the case of the novels, the paranormal is merely a smokescreen used by the author (and a character) to conceal a clever plot. And so it is with The Sittaford Mystery. The table-turning is not merely atmospheric but a vital part of the plot concocted by the murderer (i.e. the author) to camouflage his intentions and, essentially, provide him with an alibi.

All of the notes for The Sittaford Mystery are contained in 40 pages of Notebook 59. Also in this Notebook are the notes for Lord Edgware Dies and brief notes for some of the Mr Quin stories. The Sittaford notes are very organised and there is little in the way of extraneous material. Most of the chapters are sketched accurately and even some of the chapter headings are included, although the chapter numbers in the Notebook do not correspond exactly with those of the published novel. Unusually, most of the characters’ names, with the exception of the Inspector, are also as published. The notes for the two novels sketched in this Notebook follow each other in an orderly fashion and there are no shopping lists, no breaking off to plan a stage play, no digressions to a different novel. The year 1931 was also the last of the decade in which Christie had only one title published. From 1932 onwards, starting with Peril at End House and The Thirteen Problems, Collins Crime Club published more than one Christie title per year. This increased rate of production is probably one of the reasons that the subsequent Notebooks become more chaotic.

Following in the footsteps of Tuppence Beresford in The Secret Adversary and more recently, Partners in Crime, Anne Beddingfeld from The Man in the Brown Suit and ‘Bundle’ Brent from The Secret of Chimneys, Emily Trefusis in The Sittaford Mystery is another young Christie heroine with an independent mind and a yearning for adventure. She also foreshadows Lady Frances (Frankie) Derwent in Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? and, 20 years later, Victoria Jones in They Came to Baghdad.

The first four chapters of the novel are accurately reflected in the early notes, although the time of death in the novel is amended to 5.25. Oddly, the secret of the novel upon which the alibi is based, is not mentioned at this stage and the brief summary below, while the truth, is not the whole truth.

The séance

Burnaby insists on going off to see his friend. Starts in the snow, goes up to house, rings and then goes in. Finds body, rings up doctor. Hit by sand bag (put under door for draughts). Dead two hours; could he have died at 6.15? Yes – very probably.

Inquest – Scotland Yard

Inspector – he questions Major Burnaby: Why did you say 6.15? Hums and haws – at last explains. Goes to see friend who is scientific.

Following this, Christie rather chaotically considers possible suspects before returning to the beginning of the novel. She confidently heads page 26 . . .

Chapter I At Mrs Willet’s

Major Burnaby put on his gum boots, took his hurricane lantern. Goes through snow to Mrs. Willets. Arrive at house – description. Captain Trevelyan – his qualities – 6 bungalows – first for his old friend and crony and lets the others.

Major B – Ronnie Garfield – young ass staying with invalid Aunt for Xmas

Mr Rycroft – entomologist dried up little man

Mr Duke – big square man

The conversation – the glasses – mention of it being the first Friday for two years he hasn’t gone down to Midhampton to Capt. Trevelyan. ‘I walk. What’s twelve miles – keep yourself fit.’ Looks at Violet . . . they said curves were coming in again – all for curves

Young man (journalist) arrives at hotel, accosts Major Burnaby. I’m on the staff of the Daily Wire. Overheard – young man explains – presents with cheque – No 1 The Cottages. Then gets into cottage conversation – goes out and wires to his paper. Comes back and talks loudly. Tells Burnaby he wants to photograph his cottage. Mr Enderby then goes out and finds Batman. So then things are square after all. Explains how the late captain used his name.

Each person at séance must have connection

Violet Wilton and a ne’er do well

Captain Trevelyan

Mary Trevelyan married a man called Archer – 3 sons?

Bill [Brian Pearson] the ne’er-do-well – nothing much known of him, supposed to be in Australia, really in Newton [Abbot] seeing Violet.

John, the good stay-at-home, in Town for a literary dinner. He is married – really having an intrigue with an actress. [Martin Dering?]

Another was at the theatre with a girl (Story changes – girl agrees) they give wrong theatre – play has moved there – or different actor in it yes, better – Gielgud instead of Noel Coward.

Ronald Payne, in love with Mary Archer, has come down here to persuade old uncle to do something.

Batman has married – living with wife 2 cottages away – comes in to do for him. A prize of new books has arrived for him at Batman’s.

Brief sketches of potential chapters cover eight pages and while some of the descriptions below match the published chapters, as the list progresses the matches become less faithful. It is entirely possible, of course, that the original manuscript followed this pattern and that subsequent editing resulted in the book we now know. I have added chapter numbers where the descriptions seem to tally but in some cases this is not feasible.

I Afternoon at Sittaford [Chapter 1]

II Round the Table [Chapter 2]

III Discovery at Midhampton [Chapter 3]

IV Inspector Pollock [Narracott] takes over [Chapter 4]

V At Mr and Mrs Evans [Chapter 5]

VI Inspector P and B visit lawyer – the will [Chapter 7]

VII The journalist bit [Chapter 8]

VIII Exeter and Jennifer Gardiner, Nurse – husband – names of nephews and nieces [Chapter 9]

IX James Pearson – facts about detained during his Majesty’s pleasure [Chapter 10]

X She decides on taking counsel of Mr Belling. You poor dear girl – the young gentleman – the attraction between [Chapter 11 and 12]

XI Sittaford – photograph of Major Burnaby’s cottage – Sittaford House – Mrs and Miss Willett [Chapter 13/14]

XII The Professor on Psychical Research consents to be interviewed [Chapter 16]

XIII Prolonged interview at Exeter – alibis examined

XIV Mrs Grant – her husband, Ambrose Grant – author – literary dinner

XV Looking up AG’s alibi [Chapter 24]

XVI The four – Major B out of it – the three others

XVII The Willets – nothing to be got out of them [Chapter 18]

XVIII Duke and Pollock – Duke indicates doubt of what has happened

XIX His story – engaged to Violet on way home

At the very end of the notes Christie reverts to her alphabetical method of cut and paste – assigning letters to a series of short scenes and then rearranging these letters to suit the purposes of her plot. I list the alphabetical sequence first and then her rearrangement, with comments:

A. Mrs C[urtis] full of death convict [Chapter 15]

B. Enderby and his interview with Emily – eye of God etc. [Chapter 25]

C. Young Ronald comes along – wants Emily to come and see his aunt [Chapter 17]

D. Miss Percehouse – acid spinster – Emily feels some kinship with her etc. Emily arranges with her to get a message . . . . to talk to Willetts – or Ronald goes with her. Label business. [Chapter 17]

E. She sees Violet Willett – evidently very nervous. Emily goes back for umbrella – creeps up stairs – the door. My God, will the night never come [Chapter 18]

F. Captain Wyatt and bulldog – eyes her up and down [Chapter 18]

G. Duke’s house – Inspector Pollock comes out of door [Chapter 19]

H. Emily’s interview with him [Chapter 19 and 27]

I. Enderby’s theory – before [Chapter 19]

J. Emily’s interview with Dr. Warren [Chapter 20]

K. The trunk label [Chapter 17]

L. The watch by night – Brian Pearson [Chapter 22]

M. Pollock at Exeter – Brian’s movements checked up to Thursday [Chapter 24]

N. Since then? Since then – I don’t know [This cryptic reference remains a mystery]

O. Enderby says Martin Dering not at dinner. Says he knows because Harris [Carruthers] was there – had one empty place – one side of him [Chapter 19]

P. Pollock clears up Martin Dering – the wire – answer comes all right [Chapter 27]

Q. Jennifer – either Emily or Inspector [Chapter 20]

R. Investigates her alibi – possible [Chapter 20]

S. Rycroft – name in book [Chapter 24]

T. Letter from Thomas Cronin about boots [Chapter 28]

U. Interview with Dacre the solicitor [Chapter 20]

Z. Emily interviews Mr Duke [Chapter 29]

Below are the regroupings as they appear in Notebook 59, with the relevant chapters added. The rearrangement does not follow the novel exactly but the broad outline is accurate, although for some reason the letters H, K, N and R do not appear at all. The scene F obviously gave trouble as it appears twice, each time with a question mark.

A B C F? D E [Chapters 15/17/18, apart from B which is Chapter 25]

I O G O F? [Chapters 18/19]

J Q U L [Chapters 20/22]

M S P T Z [Chapters 22/24/27/28]

A very interesting question in connection with the three novels published between 1931 and 1934 arises from a brief note in Notebook 59. As discussed in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, certain motifs – the legless man, the chambermaid, a pair of artistic and criminal friends – seemed to preoccupy Christie for several years. Similarly, she toyed on a number of occasions with the possibilities of the question ‘Why didn’t they ask Evans?’ As she approached the end of her career, in the lengthy Introduction to her 1970 novel Passenger to Frankfurt, she explained that sometimes a title was settled even before any story was in mind. She gave as an example the time that she visited a friend whose brother was just finishing the book he was reading; he tossed it aside and said ‘Not bad, but why on earth didn’t they ask Evans?’ She immediately decided that this would be the title for an as yet unwritten novel but, she wrote, she did not worry about the plot or the question of who Evans might be. That, she was sure, would come to her; as, indeed, it did – but when? She gives no date for the event and it is not mentioned in her Autobiography.

There are however a few possibilities. During the plotting of The Sittaford Mystery, page 24 of Notebook 59 reads: ‘The Inspector killed – concussion confirmed Why Didn’t they ask Evans? Ada Evans – also name of gardener.’ During the plotting of Lord Edgware Dies, page 53 of Notebook 41 reads: ‘Chapter XXVI Why didn’t they ask Evans.’ And earlier in Notebook 41 she also wrote a note to herself: ‘Can we work in Why Didn’t they ask Evans.’

When plotting The Sittaford Mystery, could Christie have possibly toyed with the idea of killing the Inspector? I think she may have intended that the Inspector be attacked and knocked unconscious, uttering the significant words as he collapsed. This theory gains some support from the fact that up to this point in the plotting the Inspector is the only investigator. Emily is not mentioned in the notes until 20 pages later, when Christie had gone back to the beginning of the novel and begun to draft individual chapters. The Sittaford Mystery has a character called Ada, and the gardeners are both involved in witnessing the will of Captain Trevelyan. Calling any of these characters Evans would have solved her dilemma. It is clear from the notes that she speculated about this possibility, as all three are questioned in the course of the investigation. And Captain Trevelyan’s batman is named Evans. He is ‘asked’ more than once and it is Emily’s final questioning of him that is responsible for drawing her attention to the fact of the missing boots – and thereby to the solution of the murder. When Christie did eventually incorporate Evans into a novel called, not surprisingly, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, the witnessing of a will was the very event that caused Evans not to be asked, because she is a bright girl who might realise that there is subterfuge afoot. For further speculation upon this intriguing enigma see the discussion on Lord Edgware Dies.

‘The Second Gong’

July 1932

Hubert Lytcham Roche is found shot dead in his locked study, but luckily one of his dinner guests is Hercule Poirot.

The short story ‘The Second Gong’ was first published in the UK in July 1932 in The Strand magazine but it was not until the posthumous 1998 UK collection Problem at Pollensa Bay that it appeared between hard covers. The reason for this is that Christie expanded and rewrote the story as ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’, one of the four novellas comprising Murder in the Mews.

Notes for it appear in three Notebooks, 30, 41 and 61, although the reference in Notebook 30 is only to the possibility of expanding it. Notebook 41 has, unusually for a short story, ten pages of notes neatly summarising the main plot at the outset, the only difference being the smashing of a window rather than a mirror. The notes reflect accurately the progress of the story with the usual changes of names and minor plot details (I have inserted the actual names used in the story against the names given in the notes):

Bullet passed through him and out to gong. Then door was locked on inside and body turned so that shot would have gone through window.

Second Gong

Girl coming down stairs late – meets boy – they ask butler – No, Miss – first gong. Secretary joins them (or girl anyway) – murderer – the shot fired from library just when he joins them

Dinner 8.15 – First gong 8.5. At 8.12 Joan comes down with Dick – butler says 1st gong (shot!). Geor Jervis joins them. Exeunt

At 7 Diana picks flowers – stain on dress. At 8.10 Diana hurries out – gets rose – tries window – is going away when shot is heard from road

Murderer shoots [victim] at 8.6 – shuts and locks door, goes out through window – bangs it and it shuts, smoothes over footprints – is in library when shot is fired.

Mrs Mulberry [No equivalent in story]

Diana Cream [Cleves] clever (adopted daughter)

Calshott – the agent – a one-armed man – ex-soldier [Marshall]

Geoffrey Keene (secretary)

John Behring – old friend – rich man [Gregory Barling]

They go in to drawing room. Diana joins them – Mrs Lytcham Roche – vague – spectral – John Behring – 2nd gong – M. Poirot. No L[ytcham] R[oche] – an extraordinary thing. Butler says still in his study. Diana mentions that he’s been very queer all day – yes, he may do something dreadful. P watches her – they go to study – locked.

Break down door – dead man – mirror – window locked – (reopened by John Behring) pistol by hand – ‘Gong’ – key in his pocket. Inspection of window – he opens it – ground – no footprints. Police sent for – questions.

John Behring

Mrs LR [Lytcham Roche]

Miss Cleves

[Geoffrey] Keene (pick[s] up from hall)

Butler [Digby]

Police satisfied – doctor a little uncertain as to mirror. Poirot goes out with torchlight – comes back – asks Joan for shoes – comes out – J with him (and Dick) Diana – Michaelmas daisies. Come, mes enfants, Shows them window (gong then?). Asks butler about Michaelmas daisy – Yes – then a few words with him.

As can be seen, the notes, telegrammatic in style, are very close to the finished story, which includes even the details of the Michaelmas daisies and the stain on Diana’s dress. The novels immediately preceding ‘The Second Gong’ – The Murder at the Vicarage, The Sittaford Mystery, Peril at End House – all appear in the Notebooks more or less as they eventually appeared in print. Rough work, if any, may have been done elsewhere and the Notebooks represented an outline as distinct from the working out of details of the plot.

The plot of ‘The Second Gong’ features one of the few experiments that Christie made with that classic situation of detective fiction – the locked room problem, where the victim is found in a room with all the doors and windows locked from the inside, making escape for the killer seemingly impossible. Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, Murder in Mesopotamia and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas also have similar situations. But fascinating though these situations can be, Christie does not make them a major aspect of any of these titles. And nor does she with ‘The Second Gong’, where the solution is disappointingly mundane.

But there is another connection with one of these titles. Both ‘The Second Gong’ and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas feature a killer faking the time of the murder in order to provide himself with an alibi. And more importantly, in both titles a character picks something off the floor, obviously an important clue as it gets a note of its own above, ‘Picks up from hall’; when confronted with this fact, the killer in each case offers a different object in the hope of avoiding detection. And there is a thematic connection with the only Poirot stage play written directly for the stage, Black Coffee, premiered the year before the short story. In each case the killer proves to be the male secretary of a wealthy man.

There are no notes for the elaboration of ‘The Second Gong’ into ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’, apart from the appearance of the names Miss Lingard and Hugo Trent on a single page of Notebook 61. The plot is almost identical and although a different killer is unmasked, their position in the household is essentially the same as in the original.

Lord Edgware Dies

4 September 1933

When Lord Edgware is found stabbed in his study it would seem that his wife, actress Jane Wilkinson, has carried out her threat. But her impeccable alibi forces Poirot to look elsewhere for the culprit. Two more deaths follow before a letter from the dead provides the final clue.

Lord Edgware Dies, set amongst the glitterati of London’s West End, began life in Rhodes in the autumn of 1931 and was completed on an archaeological dig at Nineveh on a table bought for £10 at a bazaar in Mosul. It was dedicated to Dr and Mrs Campbell Thompson, who led the archaeological expedition at Nineveh, and a skeleton found in a grave mound on site was christened Lord Edgware in honour of the book.

The inspiration for the book and for the character of Carlotta Adams came from the American actress Ruth Draper, who was famed for her ability to transform herself from a Hungarian peasant to a Park Lane heiress in a matter of minutes and with a minimum of props. In her Autobiography Christie says, ‘I thought how clever she was and how good her impersonations were . . . thinking about her led me to the book Lord Edgware Dies.’

Although never mentioned in the same reverent breath as The Murder of Roger Ackroyd or Murder on the Orient Express, Lord Edgware Dies, despite its lack of a stunning surprise solution, is a model of detective fiction. The plot is audaciously simple and simply audacious and, like many of the best plots, seems complicated until one simple and, in retrospect, obvious, fact is grasped; then everything clicks neatly into place. Every chapter pushes the story forward and almost every conversation contains information to enable Poirot to answer the question, ‘Did Lady Edgware carry out her threat to take a taxi to her husband’s house and stab him in the base of the skull?’

Lord Edgware himself is in the same class as the victims from both 1938 novels, Mrs Boynton from Appointment with Death and Simeon Lee from Hercule Poirot’s Christmas; he is a thoroughly nasty individual whose family despises him and whose passing few mourn. There are also unspoken suggestions of a relationship between himself and his Greek god-like butler, Alton.

The progress of Lord Edgware Dies was mentioned sporadically by Christie to her new husband, Max Mallowan, in letters written to him from Grand Hotel des Roses, Rhodes in 1931.

Tuesday Oct. 13th [1931]

I’ve got on well with book – Lord Edgware is dead all right – and a second tragedy has now occurred – the Ruth Draper having taken an overdose of veronal. Poirot is being most mysterious and Hastings unbelievably asinine.

. . . breakfast at 8 . . . meditation till 9. Violent hitting of the typewriter till 11.30 (or the end of the chapter – sometimes if it is a lovely day I cheat to make it a short one!)

Presumably there were ‘lovely days’ at the time of writing Chapters 8 and 16!

Oct. 16th

Lord Edgware is getting on nicely. He’s dead – Carlotta Adams (Ruth Draper) is dead – and the nephew who succeeds to the property is just talking to Poirot about his beautiful alibi! There is also a film actor with a face like a ‘Greek God’ – but he is looking a bit haggard at present. In fact a very popular mixture I think. Just a little bit cheap perhaps . . .

Oct. 23rd

True, I have got to Chapter XXI of Lord Edgware which is all to the good . . . I should never have done that if you had been there . . . I must keep my mind on what the wicked nephew does next . . .

All of the notes for this novel are spread over almost 50 pages of a pocket-diary sized Notebook 41. They outline most of the novel very closely and there is little in the way of deletions or variations. Unless there were earlier discarded notes it would seem that the writing of this novel went smoothly and that the plot was well established before Christie began writing. The first page of this notebook is headed ‘Ideas – 1931’ and the first ten pages, prior to the notes for Lord Edgware Dies, contain brief notes for ‘The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest’ (1932) and an even briefer note for Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, as well as a one-sentence outline of the crucial idea behind Three Act Tragedy.

There are also two references to Thirteen at Dinner, the title under which Lord Edgware Dies appeared in the USA, but it is not clear if these two references are coincidental or if the idea of 13 guests at a dinner (as mentioned in Chapter 15) was an earlier idea that Christie subsumed into Lord Edgware Dies. The first reference lists 13 members of the Detection Club in connection with this plot (as discussed in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks), and five pages later the idea of ‘Thirteen at Dinner as a short story?’ is considered though not pursued.

Two jottings, a dozen pages apart, accurately reflect the first two chapters of the book; and in between these, in the last extract below, Christie summarises the murder plot. As can be seen, the only details to change are minor ones – the name Mountcarlin changes to Edgware, the secretary Miss Gerard becomes Miss Carroll and Martin Squire becomes Bryan Martin, although at this stage he is merely an admirer rather than a fellow actor. The Piccadilly Palace Hotel, the door ajar, the waiter and the corn knife all appear in the book.

An actress Jane W comes to see Poirot – engaged to Duke of Merton – her husband – not very bright – best way would be to kill him she drawls – Hastings a little shocked. But I shouldn’t like to be hanged. Door is then seen to be a little ajar. Martin Squire [Bryan Martin] – pleasant hearty young fellow – an admirer of Miss Wilkinson’s. He is seen next evening having supper with Carlotta

Sequence

At theatre – CA’s performance – H’s reflections – Is JW really such a good actress? Looks round – JW – her eyes sparkling with enthusiasm. Supper at Savoy – Jane at next table – CA there also (with Ronnie Marsh) – rapprochement – JW and Poirot – her sitting room – her troubles. I’ll have to kill him (just as waiter is going out) Enter Bryan (and CA). JW has gone into bedroom. B asks what did she say – means it – amoral – would kill anyone quite simply

Plot

Jane speaks to Carlotta – bribes her – a thousand pounds – to go to Mr? Jefferson’s dinner. Rendezvous at Piccadilly Palace at 7.30. They change clothes – C goes to dinner. At 9.15 J. rings her up. C. says quite alright. J goes to Montcarlin House – rings – tells butler (new) that she is Lady Mountcarlin goes in – Hullo John. Secretary (Miss Gerard) sees her from above. Shoot? Or stab? Ten minutes later she leaves. At 10.30 butler goes to room – dead. Informs police – they come. Go to Savoy – Lady M came in at half an hour ago or following morning. J kills him with corn knife belonging to her maid Eloise

Christie then considers her suspects, although this list is much shorter than the eventual cast of characters:

People

Lord Mountcarlin [Edgware]

Other man Duke? Millionaire?

Bryan Martin – actor in films with her

Lord Mountcarlin’s nephew Ronnie West – debonair Peter Wimseyish

Miss Carroll – Margaret Carroll – Middle-aged woman – a Miss Clifford

The reference to ‘debonair Peter Wimsey’ is to Lord Peter Wimsey, the detective creation of Christie’s crime-writing contemporary Dorothy L. Sayers and the hero of (at that stage) a half-dozen novels and a volume of short stories. The Clifford reference is, in all likelihood, to a member of the Clifford family at whose home the young Agatha attended social evenings.

The vital letter written by Carlotta and forwarded from her sister in Canada (Chapters 20 and 23) is sketched, but only the crucial section, containing the giveaway clue:

Arrival of a letter

he said ‘I believe it would take in Lord Mountcarlin himself. Now will you take something on for a bet. Big stakes, mind.’ I laughed and said ‘How much’ but the answer fairly took my breath away. 10,000 dollars, no more no less. Oh, little sister – think of it. Why, I said, I’d play a hoax on the King in Buckingham Palace and risk lese majeste for that. Well, then we got down to details.

And the Five Questions of Chapter 14 are listed in cryptic form:

Then Points?

A. Sudden change of mind

B. Who intercepted letter

C. Meaning of his glare

D. The pince-nez – nobody owns them – except Miss Carroll?

E. The telephone call (they will go to Hampstead)

The Notebook does include one intriguing sequence, not reflected in the book:

. . . or says I have been used as a tool – I feel ill. I didn’t know what I ought to do – letter to Superintendent of police (rang up) – letter to Bryan Martin. A telephone number Victoria 7852 . . . No, no, I forgot – he wouldn’t be there. Tomorrow will do.

A letter she writes but does not post? Or a friend comes to see her?

These would seem to be the actions of Carlotta Adams as described by her maid in Chapter 10; perhaps the original intention was to report the abandoned phone call directly. And the second reference is to the vital letter to her sister, the facsimile of which, in Chapter 23, gives Poirot the clue that eventually solves the case.

Page 53 of Notebook 41 throws a further intriguing sidelight on Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?. The following note appears under a heading:

Chapter XXVI

Why didn’t they ask Evans

Ah! I can see it all now – Evans comes. Questions about BM [Bryan Martin]. She answers – pince-nez left behind

This refers to Chapter 28 of Lord Edgware Dies and the questioning of Carlotta’s maid, Ellis. At the end of the previous chapter Poirot has a revelation when, passing a cinema-goer in the street, he overhears the observation, ‘If they’d just had the sense to ask Ellis . . .’; or, in other words, ‘Why didn’t they (have the sense to) ask Ellis.’ It is entirely possible that the writing of Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? followed closely on the completion of Lord Edgware Dies. Although there are no notes for the later novel its serialisation began the same month, September 1933, in which Lord Edgware Dies was published. Christie possibly felt that the questioning of Evans/Ellis, and the intriguing reason for the lack of questioning, deserved a more elaborate construction than the one given in Lord Edgware Dies. And so she wrote Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, where the identification and questioning of Evans is the entire raison d’être of the book. Is it entirely coincidental that the Evans of the later novel is also a maid? For further discussion of the Ellis/Evans enigma see the notes on The Sittaford Mystery.

Three Act Tragedy

7 January 1935

Who poisoned Reverend Babbington at Sir Charles’s cocktail party? And, more bafflingly, why? What became of Sir Bartholomew’s mysterious butler Ellis? What secret did Mrs de Rushbridger hide? In the last act Poirot links these three events to expose a totally unexpected murderer – and an even more unexpected motive.

Three Act Tragedy is based on one of the most original ideas in the entire Christie output. A single sentence in the Notebooks shows the inspiration for the novel and from it Christie produced a perfectly paced and baffling whodunit. In fact the book is full of clever and original ideas. Apart from the brilliant central concept we also meet a victim murdered not because of what she knows but on account of what she doesn’t know; a new conjuring trick in a clever poisoning gambit; a witty yet chilling closing line; and, unwittingly, a foreshadowing, in the final chapter title, of a famous case to come. Mr Satterthwaite, normally the partner in crime of the mysterious Mr Quin, here makes one of two appearances alongside Hercule Poirot, the other being the novelette ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’ from Murder in the Mews.

Three Act Tragedy has ideas in common with Lord Edgware Dies from two years earlier. Both are set firmly among the glittering classes; both feature a murderous member of the acting profession involved in a deadly masquerade; both feature a clothes designer and an observant playwright among the suspects; and both feature Hercule Poirot. Oliver Manders’ motorcycle ‘accident’ on the night of Sir Bartholomew’s death is the same as that engineered by Bobby and Frankie in the previous year’s Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?. A variation on the impersonation at the centre of the plot was also to appear in the following year’s book, Death in the Clouds, with a murderer disguised as a plane steward; and, in more light-hearted vein, the same ruse was the basis for the short story ‘The Listerdale Mystery’, first published in 1925. This ploy, and its reverse – a servant masquerading as an employer – is used in many Christie titles, for example The Mystery of the Blue Train, Appointment with Death, One, Two, Buckle my Shoe, Sparkling Cyanide, Taken at the Flood and After the Funeral, as well as the long short story ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’.

It is also possible that this novel is Christie’s adaptation, tongue somewhat in cheek, of that well-known cliché of classic detective fiction, the guilty butler. With Three Act Tragedy she managed a solution in which The Butler Did It – and at the same time, The Butler Didn’t Do It. And the other old chestnut, the secret passage, also gets an airing, although almost as an aside.

The notes for Three Act Tragedy are the last to outline the course of a novel accurately with little extraneous material or ideas not included in the published version. From Death in the Clouds onwards notes contain speculation and changes of mind, but the notes for titles up to, and including, Three Act Tragedy are relatively organised and straightforward.

Notebooks 33 and 66 contain the bulk of the plotting, 40 pages, but the brilliantly original basis for the book was sketched, four years before publication, in Notebook 41. This is the Notebook whose first page is headed ‘Ideas – 1931’, the first half-dozen pages of which include outlines for ‘The Mystery of the Baghdad/Spanish Chest’, ‘The Second Gong/Dead Man’s Mirror’ and a brief allusion to Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, before the detailed draft for Lord Edgware Dies. In the middle of these we find the following:

Idea for book

Murder utterly motiveless because dead man and murderer unacquainted. Reason – a rehearsal

This unique idea was left to percolate for two years before the bulk of the novel was written during 1933. Almost inevitably, the background would have to be somewhat theatrical. And from the first page of the book Sir Charles Cartwright’s ability to assume a role onstage is emphasised. Mr Satterthwaite watches Sir Charles walk up the path from the sea and observes ‘something indefinable that did not ring true’ about his portrayal of ‘the Retired Naval man’; and this is, in effect, the foundation on which the novel is built.

Notebook 33 sketches, in cryptic notes, the opening scene of the book – Sir Charles, observed by Mr Satterthwaite, climbing the hill towards his house. This is followed by a list of the characters and, apart from the mysterious Richard Cromwell, who may be the forerunner of Oliver Manders, the names listed are close to those in the published book.

The Manor House Mystery

Ronald [Sir Charles] Cartwright walks up – shiplike rolling gait – clean shaven face – not have been sure [if he actually was a sailor]. Mr Satterthwaite smiling to himself

Egg/Ray Lytton Gore

Lady Mary Lytton Gore

Richard Cromwell

Mr and Mrs Babbington

Sir Bartholomew Frere [Strange]

Capt. and Mrs Dakers

Angela Sutcliffe

Satterthwaite

Captain Dacres – bad lot – little man like jockey

Mrs Cynthia Dacres runs dress shops (Ambrosine)

Anthony McCrane [Astor] – playwright

Miss Hester [Milray] – secretary – dour ugly woman of forty-three

The title at the top of the page – ‘The Manor House Mystery’ – is a generic and inadequate one and does not appear again. Three Act Tragedy is more dramatic and is in keeping with the theatrical theme – an actor, a playwright, a dress designer, a masquerade and the motive of a rehearsal.

The all-important discussion of Ellis, the butler, and his mysterious disappearance is sketched, as is the possible connection between the two fatal dinner-parties:

Bit about butler

Chapter II

Interview with Johnson – mellow atmosphere. Then it must be this fellow, Ellis; tells all about butler – not there a fortnight – questioned by police – not seen to leave house but be left – looks fishy. Says Miss Lytton Gore told him about other death. Must be some connection but was likely to be the butler. Why did the fellow disappear if he hadn’t got a guilty conscience?

Port analysed – found correct. Inspector comes in – talks about nicotine poisoning. [Second Act, Chapter 2]

London – Egg arrives over to dine with them – pale, wounded looking. The position – the three of us – questions. Are the deaths of Sir B[artholomew] and B[abbington connected?]

Yes

If so, what people were at one and which at the other

Miss Sutcliffe, Captain and Mrs Dacres, Miss Wills and Mr Manders

You can wash out Angela and Mr Manders

Egg says can’t wash out Miss Sutcliffe. I don’t know her

Mr S says can’t wash out anybody

She has washed out Mr Manders

Egg agrees [Second Act, Chapter 7]

Notebook 66 opens when the investigation is well under way and the interviews with the suspects are divided between the self-styled detectives. The first page is headed:

Division of work

P suggests Egg should tackle Mrs Dacres; C[harles Cartwright] Freddie D[acres] and A[ngela] S[utcliffe]; S[atterthwaite] Miss Wills and O[liver] M[anders]. Says Miss Wills will have seen something. C. says S. do AS – will do the Wills woman. P suggests S. should do OM [Third Act, Chapter 5]

Miss W[ills]

Sir C. – birthmark on butler’s arm. She gets him to hand her the dish. As he goes out looks back – her smile was disquieting in the extreme. She writes in a little book. [Third Act, Chapter 9]

An experiment – I will give the party. Charles stays behind – the glasses etc. Miss Will’s face – P appeals for anyone to tell anything they know [Third Act, Chapter 11]

The third death, that of Mrs de Rushbridger, and the revelatory discussion of the play rehearsal are also sketched briefly.

Mr Satterthwaite and Poirot go to Yorkshire. Mrs R dead – a small boy got it from a man who said he got it from a loony lady – ‘Bit loony she was.’ She cannot speak now, says Poirot. This must be stopped – then is someone else in danger [Third Act, Chapter 13]

Happy families – I ask for a pack of cards – I get them. Mrs Mugg – the Milkman’s wife – Egg explains. P says he hopes she will be very happy. She goes off to dress rehearsal of Angela Sutcliffe’s play by Miss Wills – Little Dog Laughed.

Tiens – I have been blind – the motive for the murder of Mr Babbington [Third Act, Chapter 14]

There are two interesting points to consider about this novel. The first is a further variation on the Evans/Ellis issue. As discussed in the notes for The Sittaford Mystery and Lord Edgware Dies, the cryptic note in Notebook 41 – ‘Can we work in Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?’ – could conceivably also apply to Three Act Tragedy. Ellis/Evans in Lord Edgware Dies and Evans in The Sittaford Mystery both provide vital clues that lead to the solution of the mystery. And if Poirot had been able to question the missing Ellis of Three Act Tragedy, he would almost certainly have prevented the death of Mrs De Rushbridger. But because he doesn’t, in reality, exist, it is obvious Why They Didn’t Ask Ellis.

The second, and little remarked upon, enigma is The Mystery of the Altered Motive. As discussed in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, the US and UK texts of The Moving Finger and Murder is Easy/Easy to Kill are considerably different. In Three Act Tragedy we find the same situation but the disparity is even more dramatic. In the UK edition of the book, during Poirot’s explanations in the final chapter, the motive attributed to Sir Charles, the supposed bachelor, is that, unknown to most people, he is actually married: ‘And there is the fact that in the Haverton Lunatic Asylum there is a woman, Gladys Mary Mugg, the wife of Charles Mugg’ (Sir Charles’ real name). And, Poirot explains, Sir Bartholomew Strange as ‘an honourable, upright physician . . . would not stand by silent and see you enter into a bigamous marriage with an unsuspecting young girl’ (Egg). During Chapter 12 of the Third Act, Sir Charles tells Egg about his real name but otherwise the reader has no reason to suspect that he already has a wife, albeit one confined to an asylum.

In the US edition, however, it is Sir Charles, and not his wife, who is insane and as Poirot clarifies, ‘In Sir Bartholomew he saw a menace to his freedom. He was convinced that Sir Bartholomew was planning to put him under restraint. And so he planned a careful and extremely cunning murder.’ And, as he is being led away, Sir Charles breaks down – ‘His face . . . was now a leering mask of impotent fury. His voice rang shrill and cracked . . . Those three people had to be killed . . . for my safety.’ Melodramatic descriptions aside, it must be admitted that of the two potential motives, this one is by far the more compelling.

The reason for this change is more difficult to explain. And it inevitably leads to the question ‘Which is the original version?’

The amended denouement means that certain passages in the book which foreshadow the altered motive are significantly different. The most crucial changes occur in Chapters 7 and 26 of the US edition. In Chapter 7 Sir Charles and Mr Satterthwaite interview the Chief Constable, Colonel Johnson. In the course of this conversation Sir Charles says, ‘I’ve retired from the stage now, as you know. Worked too hard and had a breakdown two years ago’; and extracts from Sir Bartholomew’s diary are quoted, including one significant one: ‘Am worried about M . . . don’t like the look of things’ (my emphasis). Chapter 26 includes a lengthy conversation between Poirot and Oliver Manders. None of these passages appear in the equivalent chapters (Second Act, Chapter 2 and Third Act, Chapter 14) of the UK edition. The first two changes provide the clues to Sir Charles’ breakdown, the M referring to his real name, Mugg, and showing Sir Bartholomew’s concern over Cartwright’s mental health. The third prepares the way for Manders to replace Sir Charles in Egg’s affections, although this new romantic scenario applies in either case.

However, as the book was published (both as a magazine serial and in book form) in the USA in advance of its UK publication it is likely that it was the latter edition that was altered. But the question remains: why?

In a letter (undated, as usual, but from internal evidence probably late 1972/early 1973) to her agent, Christie herself briefly refers to the problem and states, ‘I am studying the problem of Three Act Tragedy . . . in the Dodd Mead [the US edition] Sir Charles goes mad . . . I have a feeling that was what I originally wrote.’ But this is by no means conclusive; and the Notebooks throw no light on this intriguing mystery.