Chapter 6

The Third Decade 1940–1949

‘I never found any difficulty in writing during the war . . . ’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

And Then There Were None • The Body in the Library • Curtain • Murder on the Orient Express • N or M?

During the Blitz of the Second World War Agatha Christie lived in London and worked in University College Hospital by day; and, as she explains in her Autobiography, she wrote books in the evening because ‘I had no other things to do.’ She worked on N or M? and The Body in the Library simultaneously and found that the writing of two totally different books kept each of them fresh. During this period she also wrote the final adventure of Hercule Poirot, Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case; although it was always asserted that Miss Marple’s last case, Sleeping Murder, was written at around the same time, I showed in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks that the date of composition of that novel is much later. And it was at this time too that she worked on Come, Tell Me How You Live (1946), her ‘meandering chronicle’ of life on an archaeological dig.

Production slowed down during the 1940s, but only slightly. Thirteen novels, all but one, N or M? (1941), detective stories, were published; and a collection of short stories appeared towards the end of the decade. But if the quantity decreased, the quality of the writing increased. While still adhering to the strict whodunit formula Christie began, from Sad Cypress (1940) onwards, to take a deeper interest in the creation of her characters. For some of her 1940s titles, the characters take centre stage and the detective plot moves further backstage than heretofore. The central triangle of Sad Cypress is more carefully portrayed, and the emotional element is stronger, than most of the novels of the 1930s, with the possible exception of Death on the Nile. Similarly Five Little Pigs (1943), Towards Zero (1944), Sparkling Cyanide (1945) and especially The Hollow (1946) all contain more carefully realised characters than many previous novels.

In 1946 Christie wrote an essay, ‘Detective Writers in England’, for the Ministry of Information. In it she discusses her fellow writers in the Detection Club – Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh,35 John Dickson Carr, Freeman Wills Crofts, R. Austin Freeman, H.C. Bailey, Anthony Berkeley. She then adds a few modest words about herself, including this interesting remark: ‘I have become more interested as the years go on in the preliminaries of crime. The interplay of character upon character, the deep smouldering resentments and dissatisfactions that do not always come to the surface but which may suddenly explode into violence.’ Towards Zero is an account of the inexorable events leading to a vicious murder at the zero hour of the title; Five Little Pigs, her greatest achievement, is a portrait of five people caught in a maelstrom of conflicting emotions culminating in murder; Sparkling Cyanide, adopting a similar technique to Five Little Pigs, is a whodunit told through the individual accounts of the suspects, many of them caught in the fatal consequences of an adulterous triangle. And the ‘deep smouldering resentments’ of her essay are more evident than ever in the prelude to the sudden explosion of violence at a country-house weekend in The Hollow. This novel, which could almost be a Westmacott title, features Poirot, although when Christie dramatised it some years later, she wisely dropped him. For once, his presence is unconvincing and the detective element almost a distraction, although the denouement is still a surprise. Through all of this, she managed the whodunit factor though with less emphasis on footprints and fingerprints, diagram and floor plans, and initialled handkerchiefs and red kimonos.

And still she experimented with the detective novel form – Death Comes as the End (1945), set in Ancient Egypt in 2,000 BC, is a very early example of the crime novel set in the past; N or M? is a wartime thriller; The Body in the Library (1942) takes the ultimate cliché of detective fiction and dusts it off; and for Crooked House (1949) she wrote an ending so daring that her publishers asked her to change it.

Her only short story collection of this decade, The Labours of Hercules (1947), is also her greatest (its genesis and history is discussed in detail in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks). Apart from her detective output she also published two Westmacott novels. One of them, Absent in the Spring (1944), was written in ‘a white-heat’ over a weekend; this was followed three years later by The Rose and the Yew Tree. As further proof of her popularity, she made publishing history in 1948 when she became the first crime writer to have a million Penguin paperbacks issued on the same day, 100,000 each of ten titles.

After a lacklustre stage adaptation, by other hands, of Peril at End House in 1940, she wrote her own stage adaptation of Ten Little Niggers in 1943, thoroughly enjoying the experience; and dramatisations of two of her ‘foreign’ novels, Appointment with Death and Death on the Nile, followed onstage in 1945 and 1946 respectively. And the last play of the decade was Miss Marple’s stage debut, Murder at the Vicarage, not adapted by Christie herself, appeared in 1949. One of the best screen versions of a Christie work, René Clair’s wonderful film And Then There Were None, appeared in 1945 and was followed two years later by an inferior second version of Love from a Stranger, the inaptly titled film of the excellent short story ‘Philomel Cottage’.

Her most enduring monument, The Mousetrap, began life in May 1947 as the radio play Three Blind Mice, written as a royal commission for Queen Mary’s eightieth birthday. In October of that year it also received a one-off television broadcast. The following year another play written directly for radio, Butter in a Lordly Dish, was broadcast.

During her third decade of writing Agatha Christie consolidated her national and international career, attracted the attentions of royalty and Hollywood, and experimented with radio. In continuing to extend the boundaries of detective fiction she graduated from a writer of detective stories to a detective novelist.

N or M?

24 November 1941

Which of the guests staying at the guest house Sans Souci is really a German agent? A middle-aged Tommy is asked to investigate and although Tuppence’s presence is not officially requested, she is determined not to be left out. Which is just as well, because Tommy disappears . . .

N or M? marked the return of Tommy and Tuppence. We last met them in 1929 in Partners in Crime, although the individual stories that make up that volume had appeared up to five years earlier. So this was the first time Christie had written about them for 15 years. By now they are the parents of twins Derek and Deborah, although the chronology of their lives does not bear much scrutiny. At the end of Partners in Crime Tuppence announces that she is pregnant, which would make her eldest child a teenager, at most; and yet both children are involved in the war effort. Like Miss Marple’s age and the timescale of Curtain, the chronology should not interfere with our enjoyment.

N or M? was serialised six months ahead of book publication in UK and two months earlier again in the USA. This tallies with a November 1940 letter from Christie to her agent, Edmund Cork, wondering if she should rewrite the last chapter. It was her intention to set it in a bomb shelter where Tommy and Tuppence find themselves after their flat has been bombed. As she explains in her Autobiography, she worked on this book in parallel with The Body in the Library, alternating between the two totally different books, thereby ensuring that each one remained fresh. This combination is mirrored in the brief mention – very formally as ‘Mr and Mrs Beresford’ – below, from Notebook 35.

As a couple, Tommy and Tuppence have not lost their sparkle and the subterfuge undertaken by Tuppence in the early chapters, which enables her to overcome the reluctance of Tommy and his superiors to involve her in events, is very much in keeping with earlier manoeuvres in both The Secret Adversary and Partners in Crime. In the novel Christie manages to combine successfully the spy adventure and the domestic murder mystery. There is the overriding question of the fifth-column spy but also the more personal mystery of the kidnapped child. With customary ingenuity Christie brings them both together.

Notebook 35 considers the as-yet-unnamed novel:

3 Books

Remembered death [published in the UK as Sparkling Cyanide]

The Body in the Library

Mr and Mrs Beresford

And six pages later she sketches in the opening of the book. It would seem from the notes that the fundamentals of the plot were clear before she began it. Most of the notes in Notebooks 35 and 62 are in keeping with the completed novel, although there are the usual minor name changes. Many of the notes for N or M? are telegrammatic in style, consisting mainly of combinations of names. These short scenes are often jumbled together in the final draft, the whole not needing as much detailed planning as a formal whodunit with its timetables, clues and alibis.

In the middle of the notes there are some pages of ‘real’ spy detail culled, presumably, from a book. It is a fascinating glimpse into a relatively unknown area of the Second World War, and somewhat surprising that Christie was able to access this information while the war was still in progress:

Holy figures of Santa containing Tetra (explosive)

Man in telephone booth – are numbers rearranged

Cables on bottom of Atlantic – submarines can lay wires and copy messages

Mention of ‘illness’ means spying is under observation. Recovery is at risk

And Christie experiments with creating a code herself. In Notebook 35 she sketches the notes of the musical scale and the lines and spaces of the musical stave. She adds words – CAFE, BABE, FACE – all composed from the notes of the scale, ABCDEFG. And she outlines a possible character who combines a musical background and a workplace with musical-scale initials: ‘A pianist at the BBC’.

Christie next considers potential characters, most of them very cryptically.

T and T

T (for Two)

Tommy approached by MI – Tuppence on phone – really listens – when T turns up at Leahampton – first person he sees is Tuppence – knitting!

Possible people

Young German, Carl – mother a German?

Col Ponsonby – old dug out [Major Bletchley]

Mrs Leacock (who keeps guest house) [Mrs Perenna]

Mr Varney [Mr Cayley]

Mrs Varney [Mrs Cayley]

Daughter with baby comes down to stay [Mrs Sprot]

Later in the same Notebook, she unequivocally states the ‘main idea’ of the book, though this description is only partly reflected in the novel itself:

Main idea of T and T

Woman head of espionage in England?

In fact, in the opening chapter we read of the ‘accidental’ death of the agent Farquhar who, with his dying breath, managed to say ‘N or M,’ confirming the suspicion that two spies, a male, N and a female, M, are at work in England. The concealment of this dangerous female is as clever as anything in Christie’s detective fiction and few readers will spot her; in particular, the psychology of the concealment is ingenious.

Notebook 13 has a concise and accurate outline of the book. Details were to change but this is the essence of the plot and would seem to be the first jottings. Not all of these details were to be included and others, not listed here, were to appear, but as a rough initial sketch it is possible to see that Christie had a good idea of where the book was going. The alternative title indicates that Christie possibly considered the book as a ‘second innings’ for Tommy and Tuppence:

N or M

2nd innings

Possible course of plot

T and T walk – meet – plan of campaign – T’s sons [Chapter 2]

Following incidents

Sheila and Carl together [Chapter 2]

Tuppence and Carl [Chapter 2]

Golf with Major Quincy (Bletchley) ‘too many omen’ – Commander Harvey [Haydock] has house on cliff – a coast watcher [Chapter 3 ii]

Mrs. O’Rourke [Chapter 4]

Mildred Skeffington – ‘Betty’ [Chapter 2]

Mr. and Mrs. Caley – (Varleys?)

Miss Keyes[Minton] [Chapter 3]

Mrs. Lambert and son

The foreign woman – speaks to Carl in German [Chapter 5 iii]

Kidnapping of child [Chapter 7 ii]

Carl tries to gas himself

Does T hide in Commander’s house?

Is he kidnapped on golflinks? Or go to Commander’s house – and be drugged there – the sailing boat [Chapter 9 ii]

A reference to ‘Little Bo Peep’ – ‘Mary has a little lamb’ Jack Warner Horner [Chapter 14 i]

Mrs. O’Rourke – her voice loud and fruity – really drugged teas with Mrs Skeffington

Notebook 35 has more about Carl and the foreign woman as well as the first mention of the death of the child’s mother, although nothing more about the subterfuge around that aspect of the plot. And it is in this Notebook that Christie gives her solution; unlike other books she does not seem to have considered any other names for the two killer spies.

Possible plots

T and T established – Carl immediate object of suspicion – unhappy – nervy – he and Margaret Parotta – Mrs P – sinister. Tommy and Col Lessing – play golf together – Col tells him something suspicious about someone (Mrs P?) also very much against German boy.

Tup meets foreign looking woman hanging round

Tup has letters – from her ‘sons’ – leaves them in drawers – they have been tampered with.

Child kidnapped – found alive – woman dead – documents planted on her

Information thus sent is true to inspire confidence – Col. L [Haydock] and Mrs Milly Turnbull Saunders [Sprott] are N and M

Notebook 62 lists a few more scenes. Scene B appears in the book despite its deletion in the notes:

A. Tommy – supper Haydock – discovery – hit on head – imprisoned [9 ii]

B. Deb and young man – about mothers Leamouth [10 iv]

C. Tup finds Tommy disappeared. Mrs B says never came back last night. Rung up a day later – young man says all right – not to worry. Penny plain and Tuppence coloured – Deborah – Derek [10 iii and 11 iii]

And this short final extract from the same Notebook encapsulates quite an amount of plot, although in such cryptic style that it would be impossible to make sense of it – especially the final phrase – as it stands:

The kidnapping of Betty – Mrs Sprott shoots Polish woman – with revolver taken from Mrs Keefe’s drawer – arrest of Karl – incriminating papers – initials ink on bootlaces

An accusation often levelled against Christie’s writing is that it never mirrors reality and is set in ‘Christie-time’. This adventure of the Beresfords is very much rooted in reality and features the war as part of the plot more than any other title. It is also sobering to remember that when she wrote this book the war still had five years to run. N or M? has a lot of clever touches and the interplay between Tommy and Tuppence remains as entertaining as it was on their two previous appearances. Sadly, it was the last we were to read of Tommy and Tuppence until By the Pricking of my Thumbs, over 25 years later.

The Body in the Library

11 May 1942

When the body of a glamorous blonde is found on Mrs Bantry’s library rug in Gossington Hall, she decides to call in the local expert in murder – Miss Marple. Together they go to the Majestic Hotel where Ruby Keene was last seen alive. And then a second body is found . . .

As explained above, the writing of The Body in the Library was done in parallel with that of N or M?. Thus the two very dissimilar novels, one a classical whodunit, the other a wartime thriller, would remain fresh. If indeed they were both written together, it was during 1940, as N or M?, the first to see print, appeared as a serial in the USA in March 1941. The Body in the Library was serialised in the USA in May/June 1941 and published as a novel there in February 1942. It is probable that N or M? was completed before The Body in the Library as the timescale for Basil Blake’s injuries (mentioned in Chapter 16 ii) in the Blitz, which began in September 1940, would seem to place the completion of the Marple title well into 1941.

There are references to Miss Marple’s previous successes. In Chapter 1 iv she mentions that her ‘little successes have been mostly theoretical’, an allusion to The Thirteen Problems, the last time she had featured in a Christie title. A few pages later Inspector Slack ruefully recalls his earlier encounter with the elderly sleuth in The Murder at the Vicarage; and Mrs Bantry reminds Miss Marple (as if she needed it) that the earlier murder had occurred next door to her. Sir Henry Clithering recalls her perspicuity in ‘Death by Drowning’, the last of The Thirteen Problems, in Chapter 8.

Unusually for Christie, the social reaction to the discovery of a body in Colonel Bantry’s library is remarked upon. Playful at first, with exaggerated reports circulating in St Mary Mead in Chapter 4, more serious discussion ensues in Chapter 8 ii when Miss Marple considers the potential long-term effect of social ostracism. Some years earlier in Death in the Clouds Poirot had questioned Jane Grey and Norman Gale about the practical effects on their lives, and businesses, of involvement in a murder, but he was considering motive and not social reaction.

The main plot device of this novel – the interchangeability of bodies – is very similar to that of the previous year’s Evil under the Sun. In that novel, in order to establish an alibi a live body masquerades as a dead one; in The Body in the Library one dead body is intentionally misidentified as another, again in order to establish an alibi. This sort of ploy was available to detective fiction only in the days before DNA evidence and the enormous strides in forensic medicine. Despite its light-hearted beginning there is a genuinely dark heart to The Body in the Library, with its use of a totally innocent schoolgirl as a ‘decoy’ body, chosen solely on the basis of her similarity to the ‘real’ corpse, Ruby Keene. This is the earliest example in Christie’s oeuvre of the murder of a child (apart from the almost incidental murder of Tommy Pierce in Murder is Easy) and unlike later examples – Dead Man’s Folly and Hallowe’en Party – the victim is cold-bloodedly selected and murdered solely to provide a corpse.

Notes for this novel are contained in six Notebooks, the bulk of them in Notebook 62. The plot variations are minimal, leading to the conclusion that Christie had sketched the book mentally before she began serious work on it. And in her Autobiography, she admits that she had been thinking about the plot for ‘some time’. One note, in Notebook 35, is however at strange variance with the finished novel; the ‘disabled’ reference could have inspired Conway Jefferson, but otherwise the only similarity is ‘Killed somewhere else?’

Body in Library

Man? Disabled? Sign of power? No name on clothes

Inhaling Prussic acid vapour (glucose) Manager of a disinfecting process. Killed somewhere else?

An earlier draft, from Notebook 13, outlines the basic plot device – the switch of the bodies and the misidentification – but many of the surrounding details are different. Oddly, one of the conspirators in this first draft is Ruby Keene, the victim in the published novel. At this stage in the planning there is no mention of Conway Jefferson, who provides the motive, and his extended family, which provides most of the suspects. The Girl Guide, the buttons, the bleached blonde – all these plot elements are in place, though as yet the background is not filled in:

Body in Library

Mrs. B – awaiting housemaid etc. – telephone to Miss Marple. Peroxide blonde connected with young Paul Emery [Basil Blake] – rude young man who has fallen out with Bantry and who had a platinum blonde down to stay (scandal). Paul is member of set in London – real murderer has it in for him – dumped body on him – Paul takes it up to Bantry’s house or real blonde girl knew Paul’s blonde girl and about cottage – so decoyed Winnie there (with key from friend). Body is really Girl Guide decoyed by Mavis who pretends she has film face. She and man make her up after she is dead. Paul proves he was in London at party at 11 pm. Really arrives home about 3 – finds dead girl – is a bit tight – thinks we’ll push her onto old Bantry.

Now – why?

Idea is that Mavis de Winter, night club dancer, is dead.

Say: Ruby Keene, Mavis de Winters, were friendly in Paris – come over here – live separately or share flat. Ruby Keen goes to the police – her friend disappeared – went off with man. She identifies body as Mavis – Mavis was fond of Mr Saunders. Mr. S has alibi because he was seen with Mavis after certain time. Later Body of Mavis is killed and burnt in car – girl guides uniform found.

Why variants

Idea being to kill Ruby Treves

This is followed by a bizarre variation, presumably taking the name Ruby as inspiration:

A. Is Ruby Rajah’s friend?

He gave her superb jewels – young man – Ivor Rudd – attractive – bad lot – takes her to England – tells her there’s been an accident – girl guide dead – fakes body – drives it down to Paul Seton’s. Later identifies it as Ruby’s body – later takes Ruby out in car and sets fire to it – girl guide buttons and badge found

Notebook 31 is headed confidently on the first page and followed by a list of characters to which I have added the probable names from the book. Then the main timetable is sketched, with a further paragraph filling in some of the details:

The Body in the Library

People

Mavis Carr [Ruby Keene]

Laurette King [Josie Turner]

Mark Tanderly [Mark Gaskell]

Hugo Carmody – legs taken off in last War – very rich [Conway Jefferson]

Step children Jessica Clunes

Stephen Clunes

Edward

Man (Mark or Steve) takes her [Mavis] to Paul’s cottage. Leaves her there – carefully asks way or draws attention to car? Body left there at (say) 9.30 – Mavis seen alive last at 9.15 in hotel. Both girls had drink. W[innie] doped at 6.30 or 7. Pansied up after being killed at 9 pm – driven ½ hours drive by Mark 9.30 to 10 – Mavis in hotel 9 to 10 – goes upstairs at 10 (killed). Mark dancing 10–12. Body in empty bedroom – [body] taken out and put in car between 12 and 1 – covered with rug. Driven off early morning – set on fire (time fuse) in wood. Mavis last seen 10 pm – did not come on and dance – car found missing, later found abandoned in St. Loo.

One of the dangers inherent in writing two books at the same time is shown in the extract below from Notebook 35, which has another possible sketch of the plot. The plot summary includes a Milly Sprott, who is actually one of the characters from N or M?. Presumably she was to be the Girl Guide character, as the list of characters that follows includes a Winnie Sprott. This extract may be the very first musings on the book.

Body in the Library Suggestions

Body immature – yellow bleached hair – extravagant make-up – (really girl guide – lost – or a VAD – adenoidy). Suggestion is actress – handbag with clippings of theatrical news – revue – chorus – foreign artist. Body planted on young artist who has had row with Col B – (in war – military service etc.) and who has had blonde girl friend down. He plants her on Col B with help of real blonde friend. She can turn up later alive and well. Does girl in London come down and identify dead girl as Queenie Race. Really QR is alive – later Queenie killed and body dressed in Guide’s clothes.

Why was Milly Sprott killed – she saw too much – or overheard it? She is identified by Ruby – Ruby is accomplice of villain

Body L[ibrary]

Calling the Bantry etc.

Platinum blonde – everything points to young Jordan

Body

Blonde girl

Young Jordan’s friend

Winnie Sprott – girl guide

Mrs Clements – Brunette

Ruby Quinton – actress

Identified by best fr sister or friend or gentleman friend

Why?

Real Ruby engineers whole story – she – young man – life insurance?

Notebook 62 lists individual chapters and although the chapter headings do not tally, the material covered is as it appears in the novel. The names too are mostly retained, although Col. Melrose becomes Melchett, and Michael Revere and Janetta transform into Basil Blake and Dinah Lee:

The Body in the Library

Chapter I

Mrs B housemaid etc. Miss Marple comes up and sees body

Chapter II

Col Melrose – his attitude to Col B – Michael Revere and his blonde. Col M goes down there – M[ichael] in very bad temper – got down after party. Arrival of Janetta [‘his blonde’]

Chapter III

Melrose in his office – Inspector Slack – missing people. Who came down by train the night before? Lot of people at station. Bantrys – Mrs B went to bed early – Col B out at meeting of local Conservative Association

Chapter IV

Arrival of Josie – she is taken to the hall – sees body – Oh Ruby all right. Story begins to come out – Conway Jefferson – Mrs Bantry knows him

Chapter V

At hotel – Jefferson – Adelaide – Mark – Raymond (the pro) – evidence about girl

Chapter VI

Mrs B finds Jefferson – old friend – Miss M with her

Chapter VII

Adelaide and Miss M and Mrs B – Josie and Raymond

In the middle of these listings Christie sketches what she refers to as the ‘real sequence’, the mechanics of the murder plot, as well as a list of the characters. The deletions suggest that she amended this afterwards to reflect the eventual choices:

Real sequence – Winnie King leaves rally 6.30 – goes with Josie to hotel – drugged in tea – put in empty bedroom. After dinner 9.30 Mark takes girl to car and drives her to bungalow (Friday night). Strangles her 10 and puts her in – drives back – Ruby is on view 10 to 10.30 – then killed with veronal or chloral – put in room by Josie’s. 5 am – Mark and Josie take her down to car – (pinched from small house in street . . . young man’s car) Josie Mark drives her out to wood – leaving trail of petrol – gets away – walks back – arrives in time for breakfast or his bathe?

People

(Josie!) Josephine Turner

Ruby Keene

Raymond Clegg [Starr]

Conway Jefferson

Adelaide Jefferson – Rosamund?

Peter Carmody

Mark Gaskell

Then

Bob Perry (car trader)

Michael Revere Basil Blake

Diane Lee Dinah Lee

Mrs Revere Blake

Hugo Trent Curtis McClean (Marcus)

Pam Rivers [Reeves]

Basil Penton

George Bartlett

Reason why Miss Marple knows

Bitten nails

Teeth go down throat (mentioned by Mark). ‘Murderers always give themselves away by talking too much’ [Chapter 18]

Abandoning her list of chapters, Christie briefly sketches some scenes all of which appear in the second half of the novel, although the combination of characters sometimes varies:

A. Interviewing girls – Miss M present [14 ii]

B. Col Clithering interviews Edwards [14 i]

C. Col C and Ramon [13 iii but with Sir Henry]

D. Addie and Miss M [12 ii but with Mrs. B]

E. Mark and Mrs B or Miss M [12 iv but with Sir Henry]

F. Mrs B and Miss M [13 iv]

G. Doctor and Police [13 i]

In her specially written Foreword for the 1953 Penguin edition of The Body in the Library, Christie explains that when she tackled one of the clichés of detective fiction – the body in the library – she wanted to experiment with the convention. So she used Gossington Hall in St Mary Mead and Colonel Bantry’s very staid, very English library but made her corpse a very startling one – young and blonde, with cheap finery and bitten fingernails. But, as so often happens in a Christie novel, what may seem to be mere dramatics is actually a vital part of the plot. Three Act Tragedy, Death on the Nile, Sparkling Cyanide, A Murder is Announced – all feature a dramatic death, but in each case the scene in question is part of an artfully constructed plot; and so it is with The Body in the Library. Christie also considered the opening of this novel – Mrs Bantry’s dream of winning the Flower Show is interrupted by an hysterical maid with the early morning tea – the best she had written; and it is difficult not to agree.

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case

22 September 1975

A frail Poirot summons Hastings to Styles, the scene of their first investigation and now a guest house. Poirot explains that a fellow-guest is a murderer. Convinced that another killing is imminent he asks Hastings to help prevent it. But who is the killer and, more importantly, who is the victim?

‘Do you know, Poirot, I almost wish sometimes that you would commit a murder.’

‘Mon cher!’

‘Yes, I’d like to see how you set about it.’

‘My dear chap, if I committed a murder you would not have the slightest chance of seeing – how I set about it! You would not even be aware, probably, that a murder had been committed.’

‘Murder in the Mews’

‘I shouldn’t wonder if you ended up by detecting your own death,’ said Japp, laughing heartily. ‘That’s an idea, that is. Ought to be put in a book.’

‘It will be Hastings who will have to do that,’ said Poirot, twinkling at me.

The A.B.C. Murders, Chapter 3

These telling and prophetic exchanges, both between Poirot and Inspector Japp, may have sowed the seeds of an idea in Christie’s fertile brain. The A.B.C. Murders was begun in 1934 and ‘Murder in the Mews’ was completed in early 1936, so both pre-dated Curtain. But, as will be seen, she had been considering a plot very like it for some years.

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case is the most dazzling example of legerdemain in the entire Christie output. It is not only a nostalgic swan song, but also a virtuoso demonstration of plotting ingenuity culminating in the ultimate shock ending from a writer whose career was built on her ability both to deceive and delight her readers. It plays with our emotional reaction to the decline, and eventual demise, of one of the world’s great detective creations, and it also recalls the heady days of the first case that Poirot and Hastings shared, also in the unhappy setting of the ill-fated country house Styles.

The return to Styles was inspired; it encompasses the idea of a life come full circle, as Poirot revisits the scene both of his momentous reacquaintance with Hastings, and of his first great success in his adopted homeland. Like Poirot himself, Styles has deteriorated from its glory days and, instead of having a family gathered under its roof, is now host to a group of strangers; and one of them (at least) has, as in yesteryear, murder in mind. And the claustrophobic atmosphere of the novel is accentuated by having only two short scenes – those depicting Mrs Franklin’s inquest and funeral and the visit to Boyd Carrington’s house – set elsewhere. The novel also toys with the vexed question of natural versus legal justice. This is not the first time that a classic Christie has explored this theme. And Then There Were None and Murder on the Orient Express are both based on this difficult concept; and Ordeal by Innocence, Five Little Pigs, Mrs McGinty’s Dead and ‘Witness for the Prosecution’, in both short story and stage versions, further explore this theme.

But as usual with Christie, and certainly the Christie of the era in which she wrote Curtain, almost everything is subservient to plot; as it was throughout her career, the theme of justice – natural versus legal, justice in retrospect, posthumous free pardons – is merely the starting point for a clever plot. Two of her best and most famous titles – And Then There Were None and Murder on the Orient Express – are predicated on this theme but in each case the moral dilemma is secondary to the machinations of a brilliant plot. In each case, in order to make her plot workable and credible she needed a compelling reason to motivate her characters. Lawrence Wargrave in the former novel, despite his status as a retired judge, needs to be provided with a convincing reason for his ingenious plan for mass murder; the murderous conspirators on board the famous train need an even more persuasive one. In each case miscarriage of justice fitted the bill as a motivating force better than any other; Murder on the Orient Express carries an added emotional factor – the killing of a kidnapped child despite the ransom being paid. In 1934 few more heinous crimes could be imagined, or at least written about. Discussion of justice is perfunctory in each title; plot mechanics override any philosophical consideration.

When was Curtain written? In Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks I showed that the writing of Miss Marple’s last case, Sleeping Murder, took place much later than was formerly believed, and certainly not during the Blitz of the Second World War. Because there are no dated pages among the notes for Curtain, the case here is less clear. Sad Cypress, mentioned in Chapter 3 (‘the case of Evelyn [Elinor] Carlisle’), was published in March 1940 with a US serialisation beginning in November 1939. The address on the manuscript of Curtain is ‘Greenway House’, which Christie left in October 1942 on its requisition by the US navy. These are the two parameters on the writing of Curtain.

But from the evidence of the Notebooks it would seem that it was written earlier, rather than later, than previously supposed. The clearest evidence for this is in Notebook 62. The early pages of this Notebook contain the notes for the stories that make up The Labours of Hercules, beginning with ‘The Horses of Diomedes’ on page 3 and ‘The Apples of the Hesperides’ on page 5. The first page contains a short list of ‘Books read and liked’ and the latest publication date involved is 1940. (The list includes Overture to Death, the 1939 Ngaio Marsh title and her first to be published by Collins Crime Club.) Sandwiched between this list and the first page of notes for ‘The Horses of Diomedes’ is a page headed unequivocally ‘Corrections Curtain’; page 4 continues with the corrections and the final revisions appear below the half-page of notes for ‘The Apples of the Hesperides’; these stories were published in The Strand in June and September 1940 respectively. Combined with the reference on the first page of the novel to ‘a second and a more desperate war’, this would seem to place the writing of this novel in the early days of the Second World War.

For the reader, the main difficulty with Curtain is one of fitting the case into the Poirot casebook, containing as it does inevitable chronological inconsistencies for a book written 35 years before its 1975 publication. It is impossible to state with any certainty when the book is set. Although he has been married for over 50 years, Hastings has a 21-year-old daughter. Poirot has declined dramatically since his previous appearance three years earlier in Elephants Can Remember; and even the most generous estimate must place his age at around 120. In Chapter 3 there are references to cases that were all written, and published, during the late 1930s or early 1940s – ‘Triangle at Rhodes’, The A.B.C. Murders, Death on the Nile, Sad Cypress; the main character in the last of these is, oddly, referred to as Evelyn, instead of Elinor, Carlisle. Countess Vera Rosakoff (The Big Four, ‘The Capture of Cerberus’, ‘The Double Clue’) is also mentioned in the same chapter and the bloodstained butcher, also from The Big Four, is mentioned in passing in Chapter 5. There is a reference in Chapter 15 to the original Styles case as happening ‘20 years ago and more’; the earlier case could not have been simply ignored and this reference is vague enough to have little chronological significance.

The question that has to be asked, but unfortunately cannot be answered, is: Did Christie write Curtain intending that it would appear long after many ‘future’ cases of Poirot had been published, or did she write it as if she was writing it after many such cases had been published? Are references to ‘long ago’ (Chapter 7) actually to long ago or to the ‘long ago’ Christie imagined would have elapsed by the time the book was published? There is no indication on any of the the original typescripts of any major deletions or updating, putting paid to the theory that the resurrected manuscript received major surgery to remove obvious chronological anomalies. One of the surviving typescripts contains minor corrections, and these correspond to the list of corrections in Notebook 62, which seems to date from the early 1940s, possibly 1940 itself.

But if you accept that the book was written many years prior to publication and treat it as a ‘lost’ case, then these problems disappear and it is possible to enjoy this masterwork of plotting for what it is – the ultimate Christie conjuring trick. Technically it is a master class in plotting a detective story. Arguably there is no murder, although there are three deaths. The breakdown is as follows: Colonel Luttrell attempts to murder his wife, while Mrs Franklin attempts to murder her husband; Hastings proposes to murder Allerton and is responsible for the unintentional murder (i.e. manslaughter) of Mrs Franklin; and Poirot’s ‘execution’ of Norton is followed by his own death.

Hastings’ intended murder of Allerton is foiled by Poirot, who realises what he means to do. Mrs Franklin, thanks to an innocent action on the part of Hastings, is hoist with her own petard when she unintentionally drinks the poison she intended for her husband. Colonel Luttrell’s shooting of his wife is a failure because, as Poirot puts it, ‘he wanted to miss.’ And Poirot, in effect, executes Norton. In this regard, it should be remembered that Poirot was not above taking the law into his own hands and had done so, to a greater or lesser degree, throughout his career. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Peril at End House, Dumb Witness, Death on the Nile, Appointment with Death and The Hollow, he ‘facilitated’ (at least) the suicide of the culprit. And in Murder on the Orient Express and ‘The Chocolate Box’ he allowed the killers to evade (legal) justice.

The references to Curtain are scattered over nine Notebooks. Notebooks 30, 44 and 61 each have a one-page reference, while half a dozen other Notebooks have a few pages each, but the bulk of the plotting is contained in Notebooks 62 and 65 (ten pages each) and Notebook 60 with over 40 pages. It is difficult to be sure if this was because Christie mulled it over for a long time, jotting down a note whenever she got an idea, or because the plotting of it presented a challenge to her creativity. I would incline towards the latter theory, as many of the jottings are a reiteration of the same situation with changes of name, character, profession or other minor detail. This would seem to indicate that the basic idea (Styles as a guest house and Poirot as an invalid inhabitant) remains the same and that, as she intended this to be Poirot’s swan song (and the notes would back this up), she wanted it to be stunning; as indeed it is.

In Curtain Agatha Christie played her last great trick on her public. Throughout her career she fooled readers into believing the innocent guilty and, more importantly, the guilty innocent. Her first novel made the most obvious parties the guilty ones; a few years later she made the narrator the murderer. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s she rang the changes on the least likely character – the investigating policeman, the child, the likeable hero, the supposed victim; she had everyone guilty and everyone victim. She repeated the Ackroyd trick in her last decade but made it unrecognisable until the last chapter. By the time of Curtain her only remaining least likely character was the one she chose – Poirot, her little Belgian hero. And in so doing, her title was also the only possible one – Curtain.

The idea of a ‘last case’ for Poirot was one that Christie toyed with intermittently while plotting earlier titles. The following references are scattered through seven Notebooks and all refer to such a case, often with the name Curtain included:

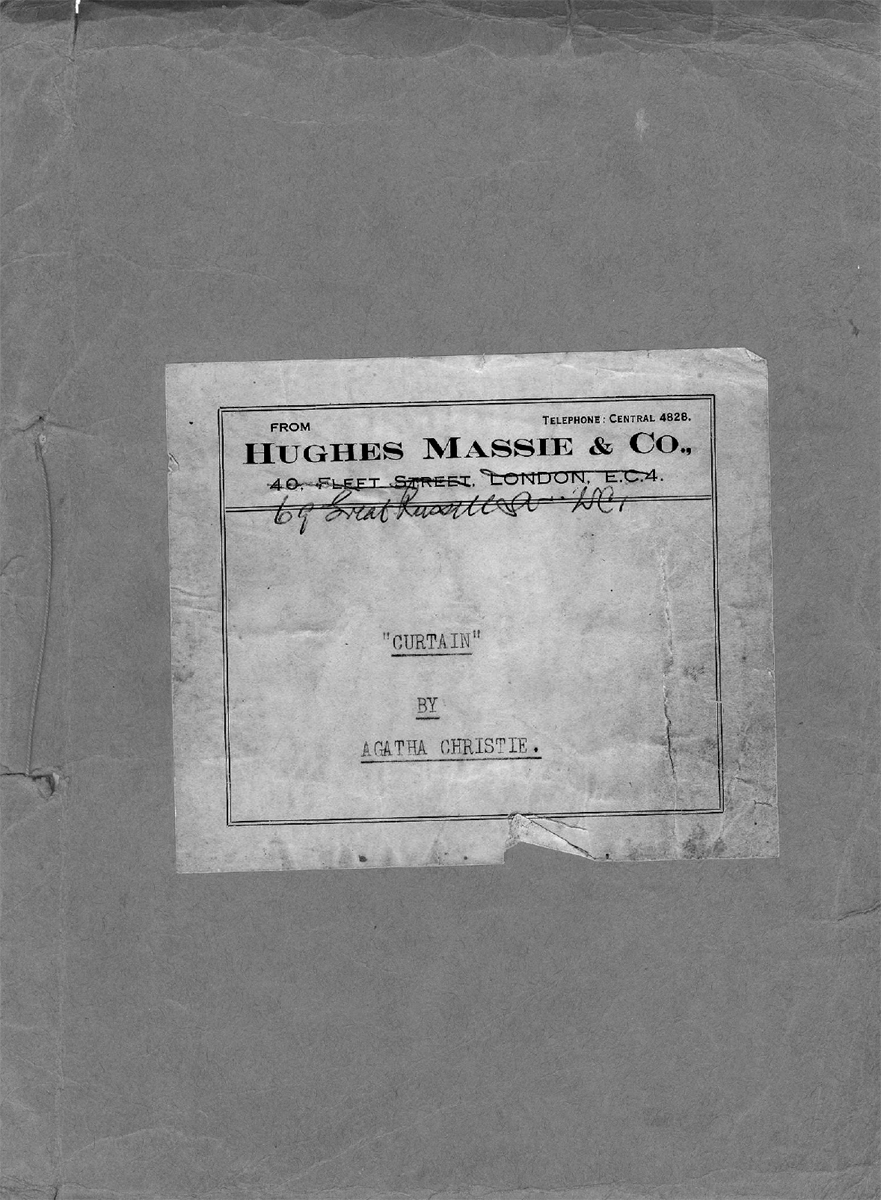

The cover of a typescript of Curtain. Edmund Cork of Hughes Massie and Co. was Christie’s agent from The Murder of Roger Ackroyd onwards.

The title page of the Curtain typescript, showing the title and name-and-address in Christie’s own handwriting.

Curtain

Poirot investigates story of death believed caused by ricin

B. Poirot’s Last Case

Styles – turned into convalescent home or Super Hotel

A. Poirot’s Last Case

History repeats itself – Styles now a guest house

Double murder – that is to say: A poisons B [and] B stabs A but really owing to plan by C (perhaps P’s last case?)

Curtain

Letter received by Hastings on boat. His daughter with him – Rose? Pat? At Styles

The Unsolved Murder – Poirot’s Last Case?

The Curtain

H[astings] comes to Styles – has heard about P[oirot]

Short Stories

Scene of one – Road up to Bassae? (Hercule’s last case)

That last, very short and cryptic example from Notebook 60 refers to the Temple of Bassae in Greece, one of the places that Christie visited on her honeymoon. Both her Autobiography and Max Mallowan’s Memoirs mention it, mainly because it involved a ten-hour mule ride. At first glance it seems that she was considering it as a possible setting for Curtain but it is far more likely that it is the last of The Labours of Hercules she had in mind, although in the end it came to nothing. This would have been totally in keeping with the international flavour of many of those cases (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks).

Possible characters are considered in six Notebooks, with Hastings and/or his daughter appearing in many of the lists:

The people

Sherman is the man who likes power – attractive

personality. Victim is Caroline

Curtain Characters

Judith – H’s daughter

Mrs Merrit – tiresome invalid

Her husband – tropical researcher medicine

Girl – B.Sc. has done work for him – very devoted

Or

Judith

Miss Clarendon – nurse companion – fine woman – experienced – mentions a ‘case’ of murder – ‘I once had to give evidence in a murder case’

Sir C. Squire – fine English type – wants to fight – H. terrifically taken by him –

2nd set of people?

Betty Rice (old friend of Landor) – A difficult life – her husband takes drugs

Dr. Amberly – clever man tropical medicine

Mrs Amberly tiresome invalid but with charm

Sir Roger Clymer – old school tie – fine fellow – has known Mrs A[llerton] as girl

Miss Clarendon – a nurse companion

A girl, Betty, and her friend come down together – she is an archaeologist or B.Sc. or something in love with Dr. Amberley

Or

Judith H’s daughter

Superior and unpleasant young man? (Mrs A’s son by former marriage?)

At Styles

Dr Amory – keen man of forty-five – wants to go to Africa, study tropical medicine

His wife, Kitty – invalid imaginaire – a blight but attractive

Governess Bella Chapstowe

Nurse companion Miss Olroyd

Martin Wright – cave man – naturalist

People

John Franklin

Adela Franklin

Langton

Nurse Barrett

? Mrs. L[angton] (Emilia?)

Roger Boyd

Old Colonel Luxmoore

Mrs Luxmoore

People there

The Darwins – Fred – patient, quiet – his wife querulous

He wants to go off to Africa – his wife won’t let him

Betty Rousdon – a girl staying there – very keen on his work

Wife’s companion – Miss Collard – principal false clue

John Selby – cave man – fond of birds – a naturalist – becomes great friends with Joan Hastings

Girl and mother (latter impossible)

Young man who wants to marry her

Has Selby a wife?

Col. Westmacott and wife – (like Luards?) some secondary resentment between them

Langdon – lame man – keen on birds – has alibi genuine for some previous case

P[oirot] – invalid – thinks Egypt etc. not George another valet – (not totally helpless)

Triangle drama

(Hastings daughter?) sec. to scientific man – nagging invalid wife who won’t let him go to S. America

Some of the characters seem to have been decided early on and, apart from name changes, remained constant until the finished novel. They include a doctor interested in tropical medicine and his invalid wife, under various names (the Amberleys/Merrits/Darwins/Amorys/Franklins); a young professional woman (Betty Rousdon/‘a Girl’/Judith) in love with him and his work; a nurse companion (Miss Collard/Oldroyd/Clarendon/Nurse Barrett); an ‘old school tie’ (Roger Boyd/Sir C. Squire/Sir Roger Clymer); a naturalist (Sherman/Martin Wright/Selby); and the owners of Styles (the Westmacotts/Luxmoores). These remain, in one form or another, through most of the notes. The young professional woman was not always Hastings’ daughter, Judith; this amendment was introduced possibly in order to give Hastings the necessary motive for murder.

Note the one-time proposal to use the name Westmacott for the owners of Styles. Although it is now well known that Mary Westmacott is a pseudonym for Agatha Christie, at the time these notes were written it was a carefully preserved secret. The reference to the Luards in the final extract is to a once-famous real life murder case in 1908 involving a love triangle.

Eventually, in Notebook 60, we get the listing that is nearest to the novel. At this point, as in some of the earlier listings, there was to be a Mrs Langton. However, Langton as a ‘loner’ makes more sense, psychologically as well as practically.

People

Judith Hastings

John Franklin

Barbara Franklin

Nurse Campbell [Craven]

Sir Boyd Carrington

Major Neville Nugent [Allerton] (seducer) really after Nurse

Col and Mrs Luttrell own the place

Miss Cole – handsome woman of 35

Langtons [Norton]

Chapter 2 of the novel lists the cases on which Poirot bases his assertion that a death will take place at Styles in the near future. Some of the scenarios sketched below, from Notebooks 60 and 65, tally closely with that chapter though, in general, details have been selected and amalgamated:

The Cases

On a yacht – a row – man pitched another overboard – a quarrel – wife had had nervous breakdown

Girl killed an overbearing aunt – nagged at her – young man in offing – forbidden to see or write to him

Husband – elderly invalid – young wife – gave him arsenic – confessed

Sister-in-law – walked into police station and admitted she’d killed her brother’s wife. Old mother (of wife) lived with them bedridden [elements of the Litchfield Case]

Curtain The Cases

Man who drinks – young wife – man she is fond of – she kills husband – arsenic? [the Etherington Case] (Langton’s her cousin – or friend?)

Man in village – his wife and a lodger – he shoots them both – or her and the kid (It comes out L[angton] lived in that village) [elements of the Riggs Case]

Old lady – the daughter or granddaughter – elder polishes off old lady to give young sister a chance [elements of the Litchfield Case]

The only scenario not to appear in any way is the first one. In many ways these recapitulations are reminiscent of a similar set-up in Mrs McGinty’s Dead, where four earlier and notorious murder cases affect the lives of the inhabitants of Broadhinny.

The following extract, from Notebook 61, appears as Idea F in a list that includes the germs of Sad Cypress (‘illegitimate daughter – district nurse’) and ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’ (‘The Second Gong – Miss Lingard efficient secretary’) and is immediately followed by detailed notes for Appointment with Death, published in 1938. As this jotting was probably written around late 1936 (‘Dead Man’s Mirror’ was first published in March 1937 in Murder in the Mews) this would put the early plotting of Curtain years ahead of its (supposed) writing. The theory that Christie wrote Curtain and Sleeping Murder in case she was killed in the Blitz begins to look questionable, as the 1940 Blitz was an unimagined horror four years earlier. Nor can it have been a book held in reserve in case of a ‘dry’ season when she didn’t feel like writing. Curtain could only be published at the end of Poirot’s (and Christie’s) career, so it can in no way be considered a nest egg. Ironically, despite the fact that this is a very precise and concise summation of Curtain, this Notebook contains no further reference to it.

The Unsolved Mystery Poirot’s Last Case?

P very decayed – H and Bella [Hastings’ wife, whom he met in The Murder on the Links] come home. P shows H newspaper cuttings – all referring to deaths – about 7 – 4 people have been hanged or surprise that no evidence. At all 7 deaths one person has been present – the name is cut out. P says that person X is present in house. There will be another murder. There is – a man is killed – that man is really X himself – executed

And this extract, from Notebook 62, mentions another important point – the absence of George and his replacement with another ‘valet’:

Hastings arriving at the station for Styles – Poirot – black hair but crippled – Georges away – the other man – a big one – quite dumb

After dinner (various people noted) P in his room gives H cases to read – X

Notebook 65 recaps this with some added detail – Poirot and Egypt, the sadism angle – but the note about warning the victim is puzzling. As he says in Chapter 3, Poirot knows from his experiences in Death on the Nile and ‘Triangle at Rhodes’ how fruitless warning a potential murderer can be. And he makes the point in the same chapter that warning the victim in this case is impossible as he does not know who the victim is to be. So why is the ‘Warn the victim?’ question answered with ‘I have done that’?

The Curtain

H comes to Styles – has heard about P from Egypt – has arthritis – Georges is back with him – Master much worse since he went to Egypt.

I am here because a crime is going to be committed. You are going to prevent it

No – I can’t do that

Warn the victim?

I have done that

It is certain to happen because the person who has made up his mind will not relent

Listen –

The story of 5 crimes – H stupefied – no motive in ordinary sense? No – spoilt – sadistic

The first ‘murder’, that of Mrs Luttrell by her husband, is considered in Notebook 60. The finished novel follows these notes accurately, even down to the quotation from Julius Caesar:

Col L shoots Mrs L – rifle not shot gun as he thinks – prepared by ‘brother’ batman story – then good shot – quick etc. Accident. He is terribly upset that night – cares for her – remembers her as ‘girl in a blue dress’ [Chapter 9]

P goes down – finds Colonel and Langton – former has been shooting rabbits – Langton flattering him. Talk of accident – he talks of shot beater etc. BC [Boyd Carrington] comes along – tells story of batman – goes off. Langton says he’ll never be bullied or henpecked – Langton quotes ‘Not in our Stars, dear Brutus but in ourselves.’ Col. shoots at rabbit – shoots Mrs – bending over flowers. Franklin and Nurse attend to her. Colonel latter comes later to Colonel – says it’s all right, Colonel all broken up – talks of her and old days – where he met her [Chapter 9]

H[astings] has conversation with Nurse. She asks about Styles – was in murder case once. Talks about Mrs Franklin. Boyd Carrington comes up ‘Good looking girl’ – come and see house. H goes with him – the house – his uncle – a very rich man – has everything – lonely. About Col L – fine shot [Chapter 7 iii]

There are three sketches of Hastings’ proposed murder and two of his unintentional murder, all from Notebook 60.

H decides (goaded by Langton) to kill ‘seducer’ of Judith – J. very secretive – plants Boyd as decoy – really when with Franklin. Boyd a boaster – fond of travel – carrying on with pretty hospital nurse. P. drugs H so that he wakes up next morning and has not killed B – his relief

Hastings plans a murder. Gets tablets from Poirot’s room or from Boyd’s own room – P drugs him

Conversation between BC, Langton, Judith and H. BC – his magnetic personality – goes off. Langton tries to persuade Judith she wouldn’t have the courage etc. He comes to reassure Hastings she wouldn’t really do anything. Then tries to warn him – is it wise to let her see so much of Atherton – married etc. He looks through glasses – shows his bird – then snatches them away – changes subject – he can see the figures. Goes in very unhappy – very worried. Personal problem ousts all others. Judith comes out of his room – H upset – speaks to her – she flares out – nasty mind – spends a night of increasing anxiety – the following day Langton tells him – rather unlovely story (quote him) – Atherton and a girl – she committed suicide. He goes to Judith – real row – H. is miserable. Hangs about – I could kill the fellow – Langton says not really – one hasn’t the guts when it comes to it. H goes upstairs to see P (with L) – passes A’s room – he is talking to someone – (nurse) that’s fine, my dear – you run up to town – I go so and so – send a wire you can’t get back – will go to other D – etc. Finds L – pulling him away. I’ll go to her – No, you’ll make things worse. L goads him – one feels responsible. H makes up his mind – it’s his duty to save her. Gets drug – waits up – P makes him drugged chocolate. He sleeps. Next morning – his relief – tells P – P reassures him – you can’t lead other people’s lives for them – points out just how he would have been found out [Chapters 11 and 12]

More points

It is Hastings who kills Mrs F. He changes glasses or cups so that she gets it, not husband

Everyone asked up afterwards. She is lying on divan – coffee – makes it herself. Crossword – everyone there – at least Nurse F. J. BC. Coles and H. Col and Mrs L L. Miss Cole. The stars – they go out to look – H puzzling over crossword. BC comes back – picks up Mrs [Franklin] in his arms – carries her out laughing and protesting. H’s eyes fill remembering Bella. J comes in – he disguises his feeling by pretending to look in bookcase – swings it round – muddle about ‘Death.’ J gives him correct word – he replaces book. Goes out with her – they come back – take their places. J by request brings medicine – F goes off to work. Dead the next day [Chapter 13]

There is an irony in the fact that having ‘saved’ Hastings from an intentional murder, Poirot is unable to save him from committing an accidental murder. And, arguably, the explanation of Mrs Franklin’s death is as big a surprise to the reader as the explanation in Poirot’s letter at the end of the book.

There are also a few versions of the death of Langton/Norton, all of them in Notebook 60, but none of them include a shooting:

Langton tells H he has an idea about murder. P stops him ‘Dangerous’ – he goes to P’s room that evening. Chocolate put in trintium. He dies at once. H woken by striking against his door – looks out – Sees L – go into own room – limp, dressing gown etc. Next day – found dead – key of his room in own pocket – locked. P says gave him trintium tablets 1/10 – by mistake in 1/100 box. P says his fault – H knows better – says to P same method – always a mistake – P agrees

P has had door key stolen – had new one made – (old room!) (a mention of P coming after Langton) P has trintium tablets for high blood pressure – takes them – induces tolerance. Shares chocolate with L – L dies. P wheels him to room – returns and plays part of L in dressing gown – hair – his own is wig – fake moustache – deliberately for Hastings. Goes in and locks door

Mrs Langton – Emilia – realises truth – tells Hastings so – kills herself – cuts throat. Langton arrested – P’s machination – limp – razor blade dropped – blood on it etc. fingerprint – L and Hast. only – L put in invalid chair and pushed to room

Emilia realises L is insane. First writes letter saying she is afraid of him, then cuts her shows herself in his dressing gown and limping, hides razor (wiped) with blood on it – then cuts her throat. P’s point is to lie – say L left him at 12.10. Or guillotine idea – L to put his head down – steel shutter

P sends for L – confronts him with story. L admits it all, shows himself in his true colours –Emilia hears it all. P gives him narcotic – goes to Emilia’s room. She has killed herself with razor. P takes L along, lets him hold razor – blood on it, on him. Then leaves room waking up H – shows himself in L’s dressing gown hiding razor in pot. H finds it

It is difficult to think of any advantage to the method, in which Mrs Langton (Emilia) plays a large and blood-soaked part, over the shooting Christie eventually settled on. Especially as the bullet-wound has the added symbolic resonance of the Mark of Cain; this was also a significant clue in And Then There Were None, making one wonder which came first. The ‘guillotine’ idea is one of the most bizarre in the entire Christie opus.

The notes for Curtain, in both volume and invention, show a professional working at the height of her considerable powers. The manipulation of plot variations, the exploration of character possibilities, the evocation of earlier crimes, all culminating in an elegiac letter from the dead, combine to display the unique gifts of the Queen of Crime.