Chapter 8

The Fourth Decade 1950–1959

‘So I was happy, radiantly happy, and made even more so by the applause of the audience.’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

After The Funeral • Appointment with Death • ‘The Case of the Perfect Maid’ • Cat among the Pigeons • Death in the Clouds • Death on the Nile • Destination Unknown • Endless Night • ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ • The Mysterious Affair at Styles • The Mystery of the Blue Train • Sparkling Cyanide • Taken at the Flood • They Came to Baghdad • They Do It with Mirrors • Three Act Tragedy • The Unexpected Guest

While she still produced her annual ‘Christie for Christmas’, the 1950s was Agatha Christie’s Golden Age of Theatre. Throughout this decade her name, already a constant on the bookshelf, now became a perennial on the theatre marquee as well. In so doing she became the only crime writer to conquer the stage as well as the page; and the only female playwright in history to have three plays running simultaneously in London’s West End. Other playwrights wrote popular stage thrillers – Frederick Knott’s Dial M for Murder and Wait until Dark or Francis Durbridge’s Suddenly at Home – and some of her fellow crime writers wrote stage plays – Dorothy L. Sayers’ Busman’s Honeymoon, Ngaio Marsh’s Singing in the Shrouds – but Christie is still the only crime writer to achieve equal fame and success in both media.

The decade began well with the publication, in June, of her fiftieth title, A Murder is Announced. This is a major title not simply thanks to its jubilee status but also because it is one of Christie’s greatest detective novels and Miss Marple’s finest hour. To celebrate the occasion Collins hosted a party in the Savoy Hotel; photos of the event show a relaxed and smiling Agatha Christie chatting with Billy Collins and fellow crime writer Ngaio Marsh as well as with actress Barbara Mullen, then appearing in the West End as Miss Marple in Murder at the Vicarage.

Her 1950s novels reflected the new social order of a post-war Britain. Elements of the plot of A Murder is Announced depend on food rationing, identity cards, fuel shortages, and a new social mobility. They Do It with Mirrors (1952) is set in a reform home for delinquents; Mrs McGinty’s Dead (1952) finds Poirot staying at an unspeakable guest-house while he solves the murder of a charwoman. Hickory Dickory Dock (1955) is set in a student hostel and Ordeal by Innocence (1958) is a dark novel about a miscarriage of justice. The female protagonist of 4.50 from Paddington (1957) makes a living, despite a university degree, as a short-term domestic help; Cat among the Pigeons (1959) combines a murder mystery with international unrest and revolution. And two titles – They Came to Baghdad (1951) and Destination Unknown (1954) – represent a return, after almost 30 years and The Man in the Brown Suit, to the foreign thriller.

In this decade the final Mary Westmacotts were published, A Daughter’s a Daughter in 1952 and The Burden in 1956. And in April 1950 Agatha Christie began to write her Autobiography, a task that would take over 15 years; it would not materialise in print until after her death. Despite this impressive range of projects, throughout the 1950s her output remained steady, although 1953, with After the Funeral and A Pocket Full of Rye, was the last year that saw more than one ‘Christie for Christmas’. During the 1950s, to the probable chagrin of Collins Crime Club, Christie concentrated her literary efforts on the stage.

Exactly a year after her fiftieth title became a best-seller, The Hollow, her 1946 Poirot novel, made its debut as a play, despite the prognostications of Christie’s daughter Rosalind, who tried to dissuade her mother from adapting what she saw as unsuitable dramatic material. The play was a success and buoyed by its reception Christie began in earnest to turn her attention to the stage. In her Autobiography she explains that writing a play is much easier than writing a novel because ‘the circumscribed limits of the stage simplifies things’ and the playwright is not ‘hampered with all that description that . . . stops [the writer from] getting on with what happens’.

In 1952 The Mousetrap began its unstoppable run. Although it began as a radio play, written at the express request of Queen Mary, who celebrated her eightieth birthday in 1947, Christie subsequently adapted it as a long short story and, finally, as a stage play. After tryouts in Nottingham, it opened at London’s Ambassadors Theatre on 25 November 1952. By the mid 1960s it had broken every existing theatrical record and it still sailed serenely on. The following year her greatest achievement in theatre, Witness for the Prosecution, opened and confirmed Agatha Christie’s status as a crime dramatist. The year after that the play duplicated its London success on Broadway, earning for its author an Edgar award from the Mystery Writers of America.

The previous three plays had been her own adaptations of earlier titles, but she now began producing original work for the stage. Spider’s Web (1954) was the first, followed by Verdict and The Unexpected Guest (both 1958). Although all three contained a dead body, something audiences had come to expect from a Christie play, in most other respects they were surprises and showed that her talents were not confined to the printed page. Spider’s Web was another commission, this one written at the request of the actress Margaret Lockwood, and was a light comedy with a whodunit element. Verdict, the only failure of the decade, was, despite its title and the presence of a murdered body, not a whodunit at all; and The Unexpected Guest was a brooding will-they-get-away-with-it – or so it seems until the final surprise. In between these titles Towards Zero, an adaptation of her 1943 novel, opened to a lukewarm reception in 1956. It was her only collaboration and it was co-adapted by Gerald Verner, a now-forgotten crime writer with a long list of titles to his credit.

On radio Tommy and Tuppence, played by The Mousetrap’s husband-and-wife team of Richard Attenborough and Sheila Sim, appeared in a 13-part adaptation of Partners in Crime beginning in April 1953. The following year the BBC broadcast an original radio play, Personal Call. The artistically and critically acclaimed Billy Wilder version of Witness for the Prosecution arrived on screen in 1957 and remains the best film version of any Christie material. And in 1956 US television cast (the unlikely) Gracie Fields in the role of Miss Marple in A Murder is Announced.

The 1950s saw The Queen of Crime expanding her literary horizons from phenomenally successful crime novelist to equally impressive crime dramatist. And in 1956, in recognition of her exceptional contribution to both, Agatha Christie was awarded a CBE.

They Came to Baghdad

5 March 1951

After losing her job and falling for a young man she meets in a London park, Victoria Jones travels to Baghdad, where she becomes involved, not entirely unwillingly, in murder, mystery and international intrigue.

‘It is difficult to believe that Mrs Christie regards this as more than a joke.’ This was the verdict from the first person at Collins to read They Came to Baghdad. Phrases such as ‘far-fetched and puerile . . . not worthy of Mrs Christie . . . wildly improbable’ pepper the report, but it goes on to say ‘it is eminently readable’ and that ‘its sheer vitality and humour and the delightful . . . Victoria Jones carry it through.’ It should be remembered that this book followed on from Crooked House and A Murder is Announced, both first-class Christie detective novels; Collins, not unreasonably, expected another in the same vein. They Came to Baghdad, the first foreign adventure story since The Man in the Brown Suit a quarter of a century earlier, was obviously a shock. And there are, undoubtedly, far-fetched aspects to the plot.

Although published in March there had been a serialisation in John Bull in January 1951. The manuscript was received by Collins in late July or early August 1950 and Christie’s agent, Edmund Cork, wrote to her on 21 August asking for clarification, for the Collins reader, of two small points – why does Carmichael use the name ‘Lucifer’ instead of ‘Edward’, when he is dying in Chapter 13; and the question of the scar on Grete Harden’s lip early in Chapter 23 which resulted in the insertion of the sentence beginning ‘Some blotchily applied make-up . . .’ In the USA, a radio and TV version were broadcast in September 1951 and on 12 May 1952 respectively. For such an atypical Christie title it is surprising that it should have been adapted so quickly for other media.

The notes for this novel are contained in three Notebooks – 31, 49 and 56. The majority of them, 95 pages, are in Notebook 56, the opening page of which reads:

The House in Baghdad

A. A ‘Robinson’ approach. Disgruntled young man – turned down – by girl – light hearted

B. T and T

C. Woman about to commit suicide in Baghdad

D. Smell of fear

As can be seen, the working title of the book was The House in Baghdad and the planning of it, to judge from a letter dated 3 October of that year, went back as far as October 1947. The ‘Robinson’ reference is puzzling but the first notes otherwise reflect the basic set-up. But the biggest surprise in this list is B – the inclusion of Tommy and Tuppence. As we shall see, they also feature in the more detailed notes later in the same Notebook, although all of their published adventures (both in novel and short story form) are firmly based in the UK. Idea C is clearly the forerunner of Destination Unknown, which was to follow three years later, and throughout the notes for They Came to Baghdad, the name Olive, the main protagonist of Destination Unknown, appears frequently, together with some of the plot of the later novel. The phrase ‘smell of fear’ runs like a motif throughout the notes, where it occurs 17 times, and it appears in the novel in Chapter 6.

Notebook 31 continues the Tommy and Tuppence idea:

Baghdad Mystery May 24th

T and T – went into Consulate – didn’t come out

Points

At Consulate – Kuwait chest – Tup. looks inside – nothing – but something showing that gunman had been there. He hid in the chest?

Sir Rupert Stein – great traveller – was to meet S. He came from Kashmir – found dead in Baghdad later – really kidnapped before?

They went to Baghdad

Beginning in Basrah – the hunted man – into the Consulate – the man through – up the stairs – meets man coming down – through door to bedroom.

Miss Gilda Martin – attention paid to her – goes to the Zia hotel – she has a little red book.

Archaeologists – including Mrs. Oliver and her brother – latter is learned gentleman horrified by her inaccurate Professor Dorman. A question of poison arises – Mrs O. tries to get it – finally does get it – then it disappears – she is very upset.

The ‘May 24th’ reference is less definite than it might at first seem. It is most likely to be 1949. If Christie was correcting the text in September 1950, after the manuscript had been read and discussed at Collins, it is unlikely that the rough notes for the novel had been first sketched at the end of May, three months earlier. (A page of Notebook 56 is dated unequivocally ‘Oct. 1949’.) At this point Tommy and Tuppence are still in the book and there are certainly some similarities between Victoria and Tuppence – resourcefulness, courage, determination and a sense of humour. There is no mention of Tommy in any of the notes. Perhaps the inclusion of the Beresfords is not that surprising when you remember that they had not appeared in print since N or M? in 1941 and would not actually appear again for another 17 years, in By the Pricking of my Thumbs.

There is a definite foreshadowing of Sir Stafford Nye from Passenger to Frankfurt in the sketch of Sir Rupert Stein and, indeed, in the eventual Sir Rupert Crofton Lee in the novel. Both characters, each with an international reputation, make their appearance in airports and both favour the dramatic look by wearing long cloaks with hoods. Sir Stafford survives his airport adventure but Sir Rupert is not so lucky.

The second shock is the mention of Mrs Oliver; and not just Mrs Oliver but her brother also. This could have been a very amusing pairing and would have probably given Christie herself an opportunity to vent her spleen on some of the nit-picking observations of critics and readers. The ‘question of poison’ would suggest a more traditional whodunit rather than a spy adventure.

The ‘Kuwait chest’ has echoes of the earlier short story ‘The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest’ and its more elaborate form ‘The Mystery of the Spanish Chest’, and The Rats, the one-act play from Rule of Three. In each case a body is discovered in such a chest. Gilda Martin may have been an early version of Victoria.

To judge from the amount of notes (well over 100 pages, many more than for any other title) and the amount of repetition in those notes, this book gave more trouble than other, more densely plotted whodunits. Again and again in Notebook 56 the opening chapters are sketched, each of them with only minor differences. This is unique within the Notebooks. These are not alternatives or an example of her usual fertility of invention – this is repetition of just one scene, which, apart from the name change, remains substantially the same throughout. Victoria Jones does not appear until 50 pages into the planning, at which point Olive is put aside until Destination Unknown. The following nine examples are some of the notes for the opening of the book and, as can be seen, there are only minor differences between them.

They Went to Baghdad

Quotation from girl’s book – Western approach – Olivia in plane – Sir Rupert Crofton Lee – great traveller and orientalist – his traveller’s cape and hood

Olive in the plane – behind Sir Rupert – his cape slips back – boil on neck – (perhaps he is flown on by RAF plane to Basrah)

Sketch (rough) – Olive arrives in Baghdad

Approaches

A. Olive – plane – Crofton Lee – boil

Tentatives

Olive arrives in Basrah – welcome by Mr. D – ordinary life – Sir Rupert – does not recognise her – supercilious she thinks

Start with A

Olive leaving England – Heathrow – Sir Rupert in plane – her thoughts – divorce – future – Baghdad – sensible – happy free life – uneasy feeling of something she doesn’t want to remember – then sees back of Sir R’s neck

Victoria Jones – a plain girl with an amusing mouth – can do imitations – is doing one of her boss – gets sack – finds young man – also sacked? Edward – ex-pilot – given me a job in an office

Parts settled – Victoria Jones in London and Edward

Vic. – Journey out – Sir Rupert – Cairo? Air hostess? – arrival in Baghdad

(A) Journey out – Victoria Mrs HC Sir R changes at Heliopolis – arrive Baghdad Aerodrome

Running alongside the Olive/Victoria approach was what Christie called the Eastern approach, in other words the events leading up to the scene in the consulate that sets the plot in motion:

Eastern approach – in the Market – Arabs – young man’s feelings – goes to Souk. In Consulate’s office waiting room – smell of fear – Richard knows it well – in war – looks around waiting room

2. Carmichael Stewart in Marshes – with Arabs – coming into civilisation

B. Carmichael – with Arabs – bazaar – something wrong

Approach B. Carmichael gets to Basrah – everything as planned – to South – passwords – all OK – to Consulate – fear – then along passage – upstairs – Richard watches him go – last time ever seen alive. Idea is for false Rupert to extract information from him

Richard – off boat at Basrah – waiting room – smell of fear – man stumbles puts in his pocket – What?

Start

A. Richard off boat – smell of fear – somehow or other something is passed to him (washing bag) – finds afterwards wonders what it is

B. In from Marshes – something wrong – does he put half – Message in Kuwait chest – specially made secret drawer – has been a conjurer – goes up steps – vanishes

Notebook 56 speculates about bringing the various strands of the plot together, although Janet McCrae does not feature in the novel. The illustration below, from the same Notebook, is similar to that drawn by Dakin in the first chapter of the book and is also the idea behind the well-known Tom Adams Fontana paperback cover from the late 1960s.

At the end of Chapter 1 of They Came to Baghdad Dakin doodles a sketch like this but the above is Christie’s own interpretation of the title from Notebook 56. The Tom Adams painting for the 1970’s Fontana paperback edition is a more elaborate and sinister version.

4 people bringing four parts of the puzzle

Schute’s [Scheele] evidence from America

Carmichael’s from Persia(?) Kashgar(?)

Sir Rupert’s from China

Janet McCrae’s from the Bahamas

1. Olive in the plane – behind Sir Rupert – his cape slips back – boil on neck (perhaps he is flown on by RAF plane to Basrah)

2. Carmichael Stewart in Marshes – with Arabs – coming into civilisation

3. Richard lands from ship – goes to Consulate – smell of fear

4. Crooks? In train? At Alep – Damascus? Stamboul – agents everywhere

Notebook 56 also considers the identity of the villain:

Is Crosbie real villain? Does he send Olive (or Vic) to Basrah on his own account?

Can Edward be young (Nazi) villain – uses Victoria. V. resembles Anne Schepp – that is why Edward picks her up

A. Does Edward (IT!) deliberately select Victoria

Or

B Edward and Victoria allies

If A, Victoria pairs with Richard? Deakin ?

If B, is villain Mrs Willard (plaster on arm?)

Overall, as the Collins reader rightly noted, the novel has great pace and readability and, if not taken seriously or examined in any detail, is a pleasant read. But it must be asked why Edward, in Chapter 2, should draw attention to ‘something fishy’ in the Baghdad set-up (thereby setting the whole novel in motion) when he is the (very surprising) villain of the piece. He could easily have invented another reason to persuade Victoria to follow him. This very basic flaw in the plot is, possibly, a reflection of the problems the book seems to have given in its creation. But as the Collins reader observed, the character of Victoria, as well as the depiction of life in Baghdad and on an archaeological dig, more than compensate.

They Do It with Mirrors

17 November 1952

Miss Marple goes to Stonygates, the reform home for young delinquents run by the husband of her childhood friend Carrie Louise. Although the atmosphere is tense, when murder is committed the victim is totally unexpected. More deaths follow before Miss Marple penetrates the murderer’s conjuring trick.

They Do It with Mirrors was serialised six months before book publication in both the UK and the USA and was Christie’s second title of 1952, following a few months after Mrs McGinty’s Dead. Leaving aside the unlikely background – a reform home – for Miss Marple, the conjuring trick at the heart of the plot is clever; although even the mention of a conjuring trick risks giving the game away immediately. The subsequent killings are, like similar deaths in later novels of the 1950s – 4.50 from Paddington, Ordeal by Innocence – unconvincing and read suspiciously like padding. The principle behind the misdirection involving Carrie Louise’s innocent tonic is similar in type to the misdirection in After the Funeral, the following year, concerning the death of Richard Abernethie. Having successfully deceived her readers for over 30 years, Agatha Christie could still devise new and infuriatingly simple tricks. And her presentation of clues remained as devious and daring as ever. Read the description of Lewis Serrocold opening the door of the locked study after the quarrel – and marvel anew.

Most of the notes, almost 30 pages, for They Do It with Mirrors are contained in Notebook 17, with brief references to the main plot device in another seven. The central idea behind this plot, the fake quarrel, was one that Christie nursed for a long time before finally incorporating it into a book. She considered numerous variations and various settings and the plotting was entangled, at different times, with both Taken at the Flood and A Pocket Full of Rye. As can be seen, that attraction went back over many years and oddly, it would seem that it was the title, or at least a reference to ‘mirrors’, that attracted her:

Jan 1935

A and B alibi A has attempted to murder B – really they both murdered C

Ideas for G.K.C.

Alibi by attempted murder. A tries murder B and fails (Really A and B murder C or C and D)

They do it with Mirrors

Combine with Third Floor Flat – fortune telling woman dead, discovered by getting into wrong flat

Plans Nov. 1948 Cont.

Mirrors

Approach – Miss M. on jury – NAAFI girl37 – Japp or equal unhappy about case – goes to Poirot. The fight between two men – (maisonette) – one clatters down – goes up again in service lift and through door – shouts for help – badly wounded – thereby they prove an alibi

Mirrors

Basic necessity – two enemies who give each other alibi. Brothers – Cain and Abel

A split B’s head open once – A bad tempered cheerful ne’er do well; B Cautious stay at home

Mirrors

The antagonism between two people providing the alibi for one. Sound of quarrel overheard – struggle and chairs – finally he comes out – calls for doctor

Mirrors

The trick – P and L fake quarrel – overheard below (actually P. does it above) L. returns and stuns him – calls for help

The ‘fake quarrel’ trick extends back as far as Christie’s first book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, where Alfred Inglethorp and Evelyn Howard feign an argument in order to allay suspicion. Death on the Nile and Endless Night also feature this deception. In They Do It with Mirrors the trick depends, like that of a conjuror, on the misdirection of an audience’s attention while the murder is actually committed elsewhere. As can be seen in the first example above, this brief note may well have inspired Death on the Nile as it preceded that novel by two years; and the ‘G.K.C.’ note was for a 1935 anthology A Century of Detective Stories, edited by G.K. Chesterton. The reference to ‘Third Floor Flat’ is to the 1929 Poirot short story of the same name; its possible combination with the ‘mirrors’ idea is echoed again in the example following, with the mention of the service lift. This dated extract is from Notebook 14, directly after the main notes for 1949’s Crooked House. The ‘Cain and Abel’ note is from the early 1950s; it appears a few pages before the rough notes for the adaptation of The Hollow as a play. The final example shows the connection with A Pocket Full of Rye, as the initials refer to Percival and Lancelot from that novel.

Notebook 63 confirms that Christie considered the title a promising one and shows an elaboration of the idea as she experiments with various combinations of male/female and A/B. The reference to 1941’s Evil under the Sun shows that this version postdates 1937’s Death on the Nile.

They Do it with Mirrors (Good title?)

Combine with AB alibi idea – A and B, apparently on bad terms, quarrel

(a) Man and Woman (?) Jealousy? He pays attention to someone else? or she does? or married couple? (too like Evil under Sun)

(b) Two men or two women quarrelled about a man (or woman) according to sex

Result – clever timing – B phones police or is heard by people in flat or being attacked by A (A is really killing C at that moment!). C’s death must be synchronised beyond any possible doubt.

A stabbed by B – then B goes off to kill X – A does double act of quarrel – ending with great shout – ‘he’s stabbed me.’

A has alibi (given by the attacked B) – B has alibi (given by injury and A’s confession) – [therefore] suspicion is narrowed to D E or F

Then she tries out completely different plots, while retaining the promising title. The first one has echoes – sisters masquerading as ‘woman and maid’ – of the Miss Marple story, ‘The Case of the Perfect Maid’, first published in 1942, and the second is somewhat similar to the Poirot case Mrs McGinty’s Dead. The third is a resumé of ‘Triangle at Rhodes’, with the addition of a quarrel and the substitution of Miss Marple for Poirot; and the final one is an original, and confusing, undeveloped scenario:

They do it with Mirrors

Idea?

Adv[ertisement] for identical twins. Really put in by twins – crooks who are not identical. Woman and maid (really sisters). The maid gives alibi etc. and talks for the first one

Mirrors

Starting Inspector (?) The Moving Finger or one of the others. Calls on Miss M – retiring – his last case – doesn’t like it – puts it to her – evidence to the P[ublic] P[rosecutor] overwhelming but he isn’t satisfied

Could Mirrors be triangle idea

Valerie – rich, immoral, man mad

Michael Peter – Air ace – married to her

Marjorie – brown mouse

Douglas – her husband – rather anxious – keen on Valerie

Miss Marple

V[alerie] poisoned – it was meant for P[eter]. Could there be quarrel overheard – M and D really M and P (pretending to be D)

Mirrors

Randal and Nicholas Harvey Derek – brothers – violent quarrel – over woman? N marries Gwynneth. Old lady killed by H and R during time when R is attacking H or by R and G

In Notebook 17 Christie arrives at the plan that she eventually adopted for the novel. She drafts the set-up twice in three pages and then proceeds to a list of characters which is remarkably close to that of the finished work:

Mrs. Gordon, old friend of Miss Marple at Ritz – asks her to come. Same age but Mrs. Gordon all dolled up etc. – vague curious woman. Worried about Loulou – married that man – all efficiency and eye glasses. Fuss over young man who attacked him – said he was his father – had previously said to several people that Churchill was his father.

Mirrors

Miss M summoned by rich friend (at school together in Italy? France?). 2 sisters – both married a good deal Mrs. B and Mrs. E. Former vague but shrewd – knows how to manage men – with Louie, Mrs. E. men know how to manage her. She is committed to this cultural scheme – by first husband. 2nd selfish artist. She has various children by first husband; by second – selfish pansy young man [and] by third. E. is hard headed character, accountant. A big trust (by D) – E. is one of principal trustees – others being old lawyer – old Cabinet Minister – later dead lawyer replaced by son – C[abinet] M[inister] replaced by Dr’s son, young man – has come to college – taken and accepted by E.

People in Mirrors

Carrie Louise – friend of Gulbrandsen

Lewis Serrocold

Emma Westingham [Mildred Strete] – daughter – plain – married Canon W. now a widow come home)

Gina – daughter of Gulbrandsen’s adopted daughter, Joy, who married unsatisfactory Italian Count, name of San Severiano – daughter back to Gulbrandsen

Walter – her young American husband – good war record – but obscure origin

Edgar – a psychiatric ‘case’ young research worker? Or secretary? a bastard and a little insane

Dr. Maverick – Resident physician under Sir Willoughby Goddard leading psychiatrist

Jeremy Faber [Stephen Restarick] – Stepson of Carrie Louise by second husband ‘bad Larry Faber’, a scenic designer in love with Gina

‘Jolly’ Bellamy [Bellever] – a Carlo [Carlo Fisher, Christie’s devoted secretary and friend], devoted to Carrie Louise – or is she?

Christian Gulbrandsen

The arrival of Miss Marple and her introduction to the inhabitants of Stonygates is sketched in Notebook 17:

Miss M arrives – met at station by Edgar – introduces himself – his statement – Winston [Churchill] is his father – C[arrie] L[ouise] – charming greeting. They see Gina out of window – with handsome dark man. ‘What a handsome couple’ says Miss M – C-L looks disturbed – not her husband – Mike – gives acting classes to boys – gets up plays etc.

Telegram from Christian

Mike or Wally to Miss M about Edgar being Montgomery’s son. Talk about Edgar – illegitimate of course – served a short prison sentence

Earlier in the same Notebook, and while Lance and Percival were still possible characters in They Do It with Mirrors, she sketched the following scenes, remarkable for their similarity to the all-important scene in the published version:

Procedure

P. asks Renee to come into room – study – they start quarrelling – not married etc. Conversation continues – her voice high and clear, he goes out by window, kills father and comes back. She stabs him – shoots him etc.

Or

Same with two brothers – violent quarrel. P’s voice heard first, then L’s – L’s continues – then P. knocked out. ‘Oh God, I think I’ve killed him’

In Notebook 43 Christie outlines the events of Chapter 7 iii with only minor differences – in the published version Dr Maverick leaves before the quarrel and returns after the shooting; and it is Miss Bellever who discovers the body.

After dinner, Gulbrandsen goes to his room – ‘I have some typing to do.’ Lewis takes medicine away from Louise – powder – calc. Aspirin – for arthritis – moment of strain. Tel[ephone] – Jolly goes – ‘Alexis has arrived at station – can we send a car.’ Lewis goes to his room – Edgar comes through window – ‘My father’ – makes scene. Goes into Lewis’s room – shuts door behind him, locks it – voices raised. Ought to break down door – Carrie Louise very calm ‘Oh, no dear, Edgar would never harm Lewis.’

Maverick says very important not to apply force – Maverick goes. Jolly rather violent about it – leaves hall. Then – ‘You didn’t know I had a revolver’ – presently sound of shot – somebody screams – no, not here – it’s outside – far away. Edgar shouting – things falling over. Then, shot inside room – Edgar calling out – ‘I didn’t mean it, I didn’t mean to.’

‘Open this door’ – Edgar unbolts it – Lewis shot not shot – missed, two holes in parapet. Then Edgar breaks down. Lewis asks Stephen to fetch Gulbrandsen or ask him for some figures. They go – Gulbrandsen shot. Then Alexis walks in.

A page of Notebook 43 is headed with a straightforward question. The possibilities are then considered, with those characters ostensibly in the clear and those still under suspicion listed separately. But as we – and the police – discover, things are not always as they seem:

Who could have shot Christian Gulbrandsen

Miss Bellever

Alexis

Gina

Stephen

Clear Gina and Stephen – off

Lewis

Edgar

Dr. Maverick

Carrie Louise

Miss Marple

And the clue of the typewriter letter is drafted later on the same page:

Bottom bit left in typewriter – or just left

Dear David

You are my oldest friend. Beg you will come here to advise us on a very grave situation that has arisen. The person to be considered and shielded is father’s wife Carrie-Louise. Briefly I have reason to believe . . .

As usual, Christie sketched ideas that never went further than the Notebook, and the following page had a few interesting ones. In the extract below, E is Lewis Serrocold of the novel; none of this sketch is used, apart from the clever adaptation of the well-known phrase, ‘Abandon hope all ye that enter here.’ Note also the possibility of using Abney (see After the Funeral) as a setting.:

Scene Abney

E’s a fanatic about delinquent children – they take them

‘Recover hope all ye that enter here’ [Chapter 5]

Secret training school for thieves and embezzlers. Director E. – under David clever master with forged credentials

C. Gulbrandsen finds out about it and goes to police – then says he made a mistake. Then shot. Police suggest young man Walters – a bit balmy – someone tells him E is his father – incites him to attack him – so as to help as cover – they do it with mirrors

After the Funeral

18 May 1953

At the family reunion following the funeral of Richard Abernethie, Cora Lansquenet makes an unguarded remark about his death – ‘But he was murdered, wasn’t he?’ When she is savagely murdered the following day it would seem that her suspicions were justified.

After the Funeral appeared in the USA, as Funerals Are Fatal, two months before its UK publication and in both countries book publication was preceded by an earlier serialisation. After the Funeral is typical Christie territory – an extended family in a large country house, and the death of a wealthy patriarch with impecunious relatives waiting for the reading of the will. That family is also her most complicated, resulting in the inclusion of a family tree.

The book’s dedication reads ‘For James in memory of happy days at Abney.’ ‘James’ was Christie’s brother-in-law James Watts, the husband of her sister Madge. They lived in Abney, a vast Victorian house built in the Gothic style, exactly as Enderby Hall is described on the first page of the novel. It was to Abney that Christie retired in 1926 to recover from the trauma of her disappearance. The house is also mentioned in the Author’s Foreword to The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding: ‘Abney Hall had everything! The garden boasted a waterfall, a stream and a tunnel under the drive!’ In Chapter 23 of After the Funeral Rosamund has a conversation with Poirot seated by such a waterfall in the garden.

There is a reference to Lord Edgware Dies in Chapter 12, and the same chapter also contains two (coincidental) references, in the space of four pages, to a Destination Unknown (the following year’s book). The distinctiveness and recognisability of backs is discussed in Chapter 16 and this would also feature in 4.50 from Paddington. And the attempted murder of Helen Abernethie, overheard down a phone line, in Chapter 20 has distinct similarities to the actual murder of Donald Ross 20 years earlier in Lord Edgware Dies, and to that of Patricia Lane in Hickory Dickory Dock, two years later.

The death of Cora is one of Christie’s most brutal and bloody murders, rivalling those of Simeon Lee in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas and Miss Sainsbury Seale in One, Two, Buckle my Shoe. But, unlike the murders in these novels, the reason for the savagery of the killing in After the Funeral is not justified by the plot and it is difficult to understand why this method was adopted by the killer or, indeed, by Christie. There is never any question about the identity of the corpse as there was in One, Two, Buckle my Shoe and there is no subterfuge about the time of death as there was in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas. Stabbing or any other blunt instrument would have met the killer’s requirement.

After the Funeral also includes one of Christie’s most daring examples of telling readers the truth and defying them to interpret it correctly. At the end of Chapter 3 we fondly imagine we are sharing the thoughts of Cora Lansquenet but, on closer examination, her name is never mentioned. The description of ‘a lady in wispy mourning’ applies equally well to her impersonator. Although the thoughts we share are perfectly believable as those of a sister in mourning, they are also capable of a more sinister interpretation when we later realise whose thoughts they actually are. This subterfuge is shared in an equally daring, and yet perfectly truthful, manner in Chapter 2 of Sparkling Cyanide.

Notebook 53 contains all of the notes for After the Funeral and they are more organised than many. They alternate with those for A Pocket Full of Rye, published later the same year. Along with the title, the basic plot appears on the first page of notes exactly as it does in the novel, with no crossings out or alternatives. The only point to change is that the ‘somebody’ who speculates about the murder of Richard is, in fact, ‘Cora’.

Throughout the notes it would seem that the plotting of this book went smoothly. Apart from one major deviation – the quick-change impersonation of housekeeper and householder – the notes accurately reflect the entire plot of the book. They proceed chronologically and there is very little deleting or revising or listing of alternatives. And, interestingly, there is no earlier brief jotting with the seed of the idea that was later to bloom into this novel. The encapsulation of the plot on the first page of Notebook 53 even includes the name of the artist of the concealed painting that provides the motive for the appallingly brutal murder.

The underlying misdirection of After the Funeral also featured in the previous year’s novel, They Do It with Mirrors.

After the Funeral

Family returning from cemetery – a meal – deceased younger sister – not been seen for many years or at all by his grandchildren etc. – Cora Lansquenet – (Somebody says – of course – he was murdered) Cora L murdered the next day. Really the CL of funeral is not CL – CL is already dead [actually drugged]. Companion kills C – Why? Contents of house are left to her including a picture? A Vermeer – she paints it over with another

As usual, one of the elements to change was the names:

The family tree (with a few question marks) of the Abernethies from After the Funeral, one of the most complicated families in all of Christie.

Characters

Cora Lansquenet – youngest daughter sister of old Mrs Mr Dent (like James). Married a rather feckless painter – lived abroad a lot

Pam and husband (actor)

Jean – Leo’s widow (2nd wife?)

Judy and Greg (photographer)

Andrea – (Miles’s wife) he doesn’t come – too delicate

George – (Laura’s son) in City

A look at the family tree shows minor differences in the eventual make-up of the Abernethies. Leo’s wife becomes Helen and the ‘2nd wife’ idea was discarded; Andrea and Miles, the hypochondriac, become Maud and Timothy; Pam becomes Rosamund with an actor husband, Michael Shane; and Judy becomes Susan, while Greg has a change of profession to chemist’s assistant. Although the comment ‘like James’ (Christie’s brother-in-law) appears after Mr Dent (the forerunner of Richard Abernethie), there is nothing to show that the character was, in fact, anything like James Watts.

It is not until some pages into the notes that Poirot is mentioned, although in the novel it is Mr Entwhistle, the family lawyer, who actually brings him into the case:

HP is got into case by doctor attending old Larraby – exhumation requested – cannot see how it can be anything but a natural death – only, of course, it could be an alkaloid etc

Christie again employs her alphabetical sequence but this time there is little rearranging. The main reordering, as it appears in the book, is the poisoning of Miss Gilchrist before she gets to Timothy’s rather than afterwards. In fact, it is partly because of the poisoning that she agrees to go to Timothy’s.

A. Mr E gets telephone call from Maude – agrees to go up [Chapter 5]

B. Before goes up – calls on George – Tony and Rosemary [Michael and Rosamund] [Chapter 5]

C. Visits Timothy and Maude [Chapter 6]

D. HP and Ent[whistle] Whole thing rests on E’s belief in Cora’s hunches – she thought it was murder – she had some basis for thinking it so she was quite willing to hush it up – therefore – murder [Chapter 7]

E. Susan finds a wig in Cora’s drawer [Chapter 11]

F. Susan arranges for Miss G to go to Tim’s [Chapter 10]

G. HP receives reports [Chapter 12]

H. HP goes to Enderby – meets Andrea [actually Helen] – her story of something wrong – (Point here is was looking at Cora) – HP represents himself to be taking a house for foreign refugees – Andrea [Maude] speaks of paint smell upsetting Timothy [Chapter 14]

I. At Timothy’s Miss G gets into her stride – gossip with daily women – nun? Miss G very surprised – same nun she is almost certain who was at Cora’s – ? Then wedding cake? To Miss G – she is delighted – taken ill – but not fatal [Chapter 15]

J. They all assemble at Enderby to choose anything from sale – some comedy? Miss G says something about wax flowers? Or something that she could not have seen [Chapter 19]

Points in conversation

A. Nuns – what they were like – same one – a moustache [Chapter 19]

B. R[osamund] asks about wax flowers on malachite table – Miss G says looked lovely there [Chapter 19]

C. Susan says Cora didn’t really sketch Polperro from a postcard [Chapter 18]

D. Talk about seeing yourself [Chapter 19]

One major sequence in Notebook 53 does not appear in the finished novel. Christie referred to it as the Hunter’s Lodge idea:

Idea like Hunter’s Lodge? Housekeeper doubles with someone else made up glamorous

This is a reference to one of Poirot’s early cases, ‘The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge’ in Poirot Investigates. He solves this case while confined to bed with influenza while Hastings travels to Derbyshire, reporting back by telegram. The plot device, which bears more than a passing resemblance to After the Funeral, depends on the ability of the murderer to effect a quick change and to appear both as housekeeper and mistress of the house within minutes of each other. Similar impersonations are adopted by the killers in The Mystery of the Blue Train, Death in the Clouds, Three Act Tragedy, Appointment with Death, Sparkling Cyanide and Taken at the Flood.

Although in Chapter 15 this idea is briefly considered, it is never a serious possibility as a solution. But the underlying subterfuge is very much the same – a domestic successfully masquerades as both mistress and maid, fooling the family and the police (and the reader) into believing someone alive when they have already been murdered. The impersonation in After the Funeral is played over a longer period and is more elaborate. And as the reader is told very early in the novel that Cora had lived abroad for over 25 years, the masquerade is perfectly feasible. Lanscombe the butler ‘would hardly have known her’; Mr Entwhistle, the family lawyer, was ‘able to see little resemblance to the gawky girl of earlier days’; and none of the younger generation of Abernethies knew her at all. At first it seems as if Christie toyed with the idea of the quick-change routine and in Chapter 15 there is an opportunity for this when Miss Gilchrist answers the door in response to a bell that no one else hears and a caller that no one else sees. Pages 26–7 of the notes consider the ramifications of such a development. But this was subsequently subsumed into the nun motif and the impersonation took on a more leisurely aspect.

Does Helen, while with Jean, see woman who collects subscriptions – herself – and immediately after appear as herself – quick change owing to geography of house – such as appearing at front door and in Hall – just calling to ask you – one moment please – two voices. Helen hurries into room where Jean is upstairs – she is in morning room. Jean rings up police – then goes down – visitor is there

Or

Visitor coming in – J says will you wait – get my purse – goes to phone tells police – comes out finds Helen. H goes down to keep him in play – gone.

Appearance of all the people

Cora – blonde hair faded curls like a bird’s nest – make up – big? plump? or a hennaed bang

Miss Earle [Gilchrist] – grey hair brushed back – Pince nez or iron-grey bob – very thin

The caller – blue grey hair well dressed – (transformation) slight moustache – dark eyes (belladonna) deep voice – well cut tweeds – large sensible feet. When Jean sees her – difference in costume wig – coat and street shoes – all removed – thrown in closet – overall and slippers – Gone! What did she come for? Things have to be got rid of – taken away in suitcase – left in train

Finally, most of Chapter 20 is sketched in the latter stages of the notes. In the first paragraph Poirot reviews all the important facts of the case as he tries to sleep (Chapter 20 ii).

P goes to bed – feels something significant said – odd business about Cora’s painting – paint – Timothy – smell of paint. Something else – something connected with Entwhistle – something Entwhistle had said – significant – and something else – a malachite table and on it wax flowers only somebody had covered the malachite table with paint. He sat up in bed. Wax flowers – he remembers that Helen had arranged them that day. A rough plan – Mr Entwhistle – the smell of paint – the wax flowers.

Although the necessary clues are here paraded for the reader, how many will appreciate their significance?

Immediately following, the scene where Helen realises the implication of what she noticed at the funeral is sketched, although this is broken into two scenes in the book (Chapter 20 iii and iv):

Helen – in the room – to see ourselves – she looks – my right eye goes up higher – no it’s my left – she made an experimental face – she put her lead on one said and said it was murder wasn’t it? And with that it came back to her – of course – that was what was wrong – excited – goes down to telephone – (or in early morning) – Mr E – do you see – she didn’t – CONK

After the Funeral contains what is probably Christie’s simplest subterfuge and one that is, in retrospect, maddeningly obvious. Even without this ploy it remains a clever but conventional detective novel. The trick played on the reader puts it straight into the classic Christie class.

Destination Unknown

1 November 1954

In order to solve the mystery of his disappearance, Hilary Craven agrees to impersonate the dead wife of scientist Thomas Betterton. She joins a mysterious group aboard a plane bound for an unknown destination and when it lands in the middle of nowhere she needs all her courage and wits.

The UK serialisation of Destination Unknown preceded book publication by two months, while US readers had to wait until 1955, when it was published as So Many Steps to Death. From this year onwards Christie produced only one title per year. This cutback in production is understandable when it is remembered that 1952 and 1953 each saw the publication of two books, as well as work on the scripts of Spider’s Web and Witness for the Prosecution.

Following only four years after They Came to Baghdad, Destination Unknown is another adventure-cum-travel story and an even more unlikely one than the earlier title. Like all Christie titles, even the weakest, it has a compelling premise, but one that is not developed or resolved in a manner we have come to expect of the Queen of Crime. The opening section dealing with the state of mind of Hilary Craven as she considers suicide could have been more profitably developed at the expense of some of the interminable travel sequences, which merely pad out the novel. Unlike other one-off heroines in earlier titles – Anne Beddingfeld38 in The Man in the Brown Suit, Victoria Jones in They Came to Baghdad, and, in a more domestic setting, Emily Trefusis in The Sittaford Mystery and Lady Frances Derwent in Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? – Hilary is not looking for either adventure or a husband. She is a divorced woman and has been a mother; in fact, it is the loss of her husband through divorce and the death of her child that causes her to agree to the seemingly outrageous suggestion that she change her method of suicide from sleeping pills to a potentially fatal impersonation. Also unlike the others, she works alone once the impersonation begins because from then she can trust no one. Destination Unknown contains none of the light-hearted scenes of the earlier They Came to Baghdad, mainly due to the fact that Victoria and Hilary are totally different characters.

There are a mere dozen pages of notes, scattered over Notebooks 12, 53 and 56; and Notebook 12 has a page dated ‘Morocco Cont[inued]. Feb 28th’.

The year is, in all likelihood, 1954. Collins were anxious as that year progressed and no book reached them. If Christie was still plotting it in February in the year of publication, this would indeed be a cause for alarm. This is somewhat reflected in Notebook 12, which has four scattered attempts to get to grips with the plot. The dated page goes on to discuss possible plot developments when Hilary has already arrived at her final destination, so it is safe to assume that most of the plotting was complete at that stage.

The notes for Destination Unknown are inextricably linked with those of They Came to Baghdad from three years earlier. Much of the sketching of They Came to Baghdad features a character named Hilary/Olive and it would seem that, to begin with, the ideas that were to be included in one novel eventually generated two. The earliest indication of this comes in Notebook 56, where four possible ideas for The House in Baghdad (an early title for They Came to Baghdad) were noted. As we have seen in the discussion of They Came to Baghdad, three of these ideas were indeed used for that novel, and one broke off to become the basis of Destination Unknown.

Notebook 12 contains notes mainly for the first half of the book, before Hilary arrives at her destination. Although they are very sketchy, most of the following ideas appear in the novel with only the usual name changes:

Morocco – Hospital – Olive dying says ‘Warn him – Boris – Boris knows – a password – Elsinore?

Ou sont les neiges – The snows of yesteryear. The Snow Queen – Little Kay – Snow, Snow beautiful snow you slip on lump and over you go. [Chapter 4]

She is vetted by Dalton . . . The instructions – tickets etc. She goes to hotel – her conversation with people. Miss Hetherington – stylish spinster; Mrs. Ferber [Baker?] – American [Chapter 5]

Hilary – goes to Marrakesh. Then to fly to Fez – small plane – or plane to Tangier. Comes down – forced landing – petrol poured over it – bodies

Fellow travellers

Young American – Andy Peters

Hilary

Olaf Ericsson [Torquil Ericsson]

Madame Depuis – elderly Frenchwoman

Carslake – business man – or could be German

Dr. Barnard [Dr Barron]

Mrs Bailer [Mrs Baker]

Nun [Helga Needham] [Chapter 8]

Morocco Cont. Feb 28th

The arrival

Start from a point or little later. Hilary is finishing toilet? Dresses – her panic – no escape. ‘That’s not my wife’ – sits on bed – fertile brain thinking out plans – injure her face? Story about wife – couldn’t come? Dead? That journalist is it Tom Betterton – the hostess comes for her – meeting with Tom – ‘Olive’ [Chapter 11]

Notebook 53 contains the background that the reader learns only at the end of the novel. Unlike her detective novels, the reader is not given the information necessary to arrive at this scenario independently. In these extracts Henslowe is the Betterton of the novel and the American professor is Caspar instead of the Mannheims of the novel. Confusingly, in the book the real wife is Olive and Hilary is the impersonator, but in the Notebook Olive appears as the impersonator.

Morocco

Henslowe – young chemist – protégé of Professor Caspar – (a world famous Atom scientist – refugee to USA). H marries C’s daughter Eva Caspar – Eva dies a couple of years after the marriage. Argument – Eva inherits her father’s genius – is a first-class physicist and makes a discovery in nuclear fission. H. murders her and takes discovery as his.

The idea of a plastic surgeon altering fingerprints is an interesting but unexplored possibility:

This disappearance business is an agency run by an old American – a kind of Gulbenkian39 – he pays scientists good sums to come to him – also plastic surgeons – who also operate on finger prints. A suspicion gets about that Henslowe is not Henslowe because he is not brilliant

And the devious Christie can be seen in the last note (‘Because he is not Henslowe?’). The obvious explanation is not the one she adopts: it is not that ‘Henslowe’ is really someone else, but that he is not the scientist that he purports to be, because his reputation was built on the genius of his dead first wife:

Olive sees real wife dying in hospital – dying words – enigmatic – but they mean something. Olive and Henslowe meet – he recognises her as his wife – why? Because he is not Henslowe?

Christie also toyed with a more domestic variation concerning the earlier murder that set most of the plot in motion:

Conman finds out about murder [of Elsa] and has a hold over him

Communist Agent?

A woman?

Just an ordinary blackmailer?

Henslowe marries again

Deliberately a communist?

Just a devoted woman?

His disappearance and journey to Morocco is planned deliberately by him. [Therefore] Olive when on his trail will eventually discover that the dead body they come across (actually the blackmailer) is a private murder by Henslowe and all the Russian agents stuff is faked by Henslowe

After four very traditional whodunits in the previous two years – Mrs McGinty’s Dead, They Do It with Mirrors, A Pocket Full of Rye, After the Funeral – Destination Unknown is a disappointment. Despite a promising opening the novel ambles along to a destination that is more unbelievable than unknown, with little evidence of the author’s usual ingenuity. The denouement of They Came to Baghdad unmasked an unexpected (if somewhat illogical) villain but there are no surprises at the climax of Destination Unknown. It is undoubtedly the weakest book of the 1950s.

The Unexpected Guest

12 August 1958

When Michael Starkwedder stumbles out of the fog and into the Warwick household, he finds Richard Warwick shot dead and his wife, Laura, standing nearby holding a revolver. Between them they concoct a plan to explain the situation before ringing the police. But who really shot Richard Warwick?

During the 1950s Agatha Christie reigned supreme in London’s West End. The Hollow led off the decade in June 1951, followed by The Mousetrap in November 1952. October 1953 saw the curtain rise on Witness for the Prosecution; Spider’s Web opened in December of the following year and Towards Zero (co-written with Gerald Verner) in September 1956. In 1958 two new Christie plays appeared – Verdict in May and The Unexpected Guest in August. With the exception of Verdict all were major theatrical successes, two of them at least, The Mousetrap and Witness for the Prosecution, assuring Agatha Christie’s eternal fame as a playwright.

Spider’s Web had been the first original Christie stage play since Black Coffee in 1930. Verdict and The Unexpected Guest continued this trend for new, as distinct from adapted, material, although both of these scripts are considerably darker in tone than Spider’s Web. To some extent all three feature attempts to explain away a mysterious death with less emphasis than usual on the whodunit element. And in The Unexpected Guest Christie sets herself the added challenge of portraying a 19-year-old who is mentally disturbed. On a more personal note, the description of the victim, Richard Warwick, has distinct similarities to Christie’s brother, Monty. Both spent part of their adult life in Africa, both needed an attendant when they returned to live in England and both had the undesirable habit of taking pot-shots at animals, birds and, unfortunately, passers-by through the window of his home. In her Autobiography (Part VII, ‘The Land of Lost Content’) she recounts Monty’s description of a ‘silly old spinster going down the drive with her behind wobbling. Couldn’t resist it – I sent a shot or two right and left of her’; this is exactly Laura’s description in Act I, Scene i of Richard’s behaviour. There, it must be emphasised, all similarities ended, as Richard Warwick is painted as a particularly despicable character.

Verdict, after a critical mauling due, in part, to a mistimed final curtain, lasted only one month but in August 1958, spirit unquenched, the curtain rose on the next offering from the Queen of Crime. Verdict was an atypical Christie stage offering; despite its title it is not a whodunit and has no surprise ending. With The Unexpected Guest she returned to more recognisable fare. Although it is, in part, a will-they-get-away-with-it type of plot, it also contains a strong whodunit element and a last-minute surprise.

Christie had, presumably, spent the intervening period, not in licking her wounds, but in setting out to prove her critics wrong by writing a new play to eradicate the failure of Verdict. Or so it seemed. But Notebook 34 shows, with an unequivocal date, that the earliest notes for this play had been drafted even before The Mousetrap had begun its unstoppable run. Three pages of that Notebook show that almost the entire plot of the play already existed. A more likely scenario, and one borne out by further notes below, is that the plotting of the play was already well advanced even before Verdict was taken off; it needed only a final polish.

1951 Play

Act I

Stranger stumbling into room in dark – finds light – turns it on – body of man – more light – woman against wall – revolver in hand (left) – says she shot him.

‘There’s the telephone –

Uh?

‘To ring up the police’

Outsider shields her – rings police – rigs room

People Vera

Julian (lover?)

Benny (Cripple’s brother)

Act II

Ends with S[tranger] accusing V[era] of lying. Julian killed him – you thought I’d shield you – (she admits it) or led up to by his realising she is left handed; crime committed by right handed person

Curtain as –

‘Julian did it’

She – ‘You can’t prove it – you can’t alter your story’

‘You ingenious devil’!

Act III

Suspicion switches to Benny having done it. But actually it is woman. Ends with her preferring S[tranger] to Julian

Characters could be

Vera (Sandra)

Julian

Mrs Gregg mother of victim

Stepmother

Barny feeble minded boy

Rosa ” ” girl

Miss Jennson – Nurse

Julian’s sister

Lydia or niece of Julian’s – hard girl

This is, in rough outline, the plot of the play; and the characters correspond closely to the eventual cast list. The only element missing is the development of the part played by ‘the Stranger’; he does not even figure in the list of characters, although a ‘stranger stumbling into room’ is the opening of the play. And yet the part he plays is vital to the surprise in the closing lines of the eventual script. The explanation for this may be simply that the final twist had not occurred to Christie when she began drafting the play. This is in keeping with other titles; the shock endings to both Crooked House and Endless Night do not form a large part of the plotting of either novel and would seem to have emerged during, rather than being inspired by, the drafting of the book. But even without the final twist The Unexpected Guest is still an entertaining whodunit.

Notebook 53 also has a concise summation of the plot, this time including a list of possible murderers. These three pages appear, unexpectedly, between pages of extended plotting of After the Funeral and A Pocket Full of Rye, both of which were completed in the early 1950s and published in 1953. The general set-up here is reflected in the finished play, although neither victim nor killer has yet been decided. By now the part played by the ‘stranger’ has taken on a more important aspect; he is given a name, Trevor and is under consideration as the murderer.

Plan The Unexpected Guest

Act I

Trevor blundering in – in fog or storm – Sandra against wall – pistol. He and she – he rigs things – rings police. Scene between them

Curtain – end of scene

Scene II

People being questioned by police

Julian Somers MP

Sandra

Nurse Eldon

Mrs Crawford

David Crawford – invalid

Or

David Etherington Sandra’s brother

Act II

Further questions

Julian and Sandra – Trevor’s suspicions. He accuses her – having tricked her with revolver

Damned if I’ll shield him

What else can you do – now? etc.

Act III

Mrs Crawford takes a hand. ‘Who really did it’ – (brightly)

Now who did?

1. Trevor the enemy from the past – his idea is to return and find body

2. Nurse? Told him about wife and Julian – his reaction is that he knew all about it – is brutal to her – she shoots him

3. Governess to child? Or to defective?

4. Defective has done it – or child

5. Mrs Crawford?

As further confirmation of the unpredictability of the Notebooks, the following extract, clearly dated November 1957, appears in Notebook 28, preceded by notes for By the Pricking of my Thumbs and followed by notes for Endless Night, both published in the late 1960s. How this gap of ten years can have happened in the middle of a Notebook and how a title from the previous decade can appear between notes for two titles from a later decade, is inexplicable; but it shows, yet again, the danger of drawing deductions or making explicit statements about the timeline of the notes, unless supported by incontrovertible proof.

There seems to be confusion in the following extract in the naming of the main female character. Earlier notes refer to her as Vera, as do the initials in this extract, but in the course of the notes she is also referred to as Ruth and/or Judith:

FOG

Nov 1957

M enters – R dead

V. revolver in hand – admits – the build up – tells her of MacGregor – dead man displayed in bad light – letter written – printed – left – then (M. rings up police?) V goes up stairs – paper bag trick – they come down – M. enters – discovery – M rings up police. Does Ruth – make some remark about lighter (Julian’s)

Scene II

Police – then family

Julian comes – lighter – he picks it up etc.

Act II

Police again or a police station – or his hotel and V. comes there?

Ends with Julian and V

His saying ‘You did not kill him – didn’t know even how to fire a revolver’

Act III

(Cast?) V[era]

M[ichael and/or MacGregor]

Jul[ian]

Police Insp.

“ S[ergeant]

Mrs Warwick

Judith Venn [no equivalent]

Bernard Warwick [possibly Jan]

Crusty [possibly Miss Bennett]

Angell – Manservant (Shifty)

Crusty works on Bernard or Judith or Bernard begins talking

Points to decide

Judith (angry because R. chucks her out). If so, Bernard is induced by her to confess or even boast. He is taken away. M. clears him and breaks down J. [M] says to V. (good luck with J.) he is M[acGregor]

Or

Bernard boasts to killing him – he is killed – cliff? window? etc.

Case closed. Then M springs his surprise

As can be seen, at this point the play is referred to as ‘Fog’; and the same title appears in other Notebooks, once with the addition of ‘The Unexpected Guest’ in brackets. As a title ‘Fog’ has its attractions. In both the physical and metaphorical sense fog plays an important part in the play. ‘Swirls of mist’ are described in the stage directions and fog is necessary to lend credence to Starkwedder’s story of crashing his car; and, of course, the other characters, and the audience, are in a fog of doubt throughout the play. Unusually for a Christie play (with a UK setting) the scene is specifically set near the Bristol Channel, and the fog-horn sounds a melancholy note periodically throughout the action of the play. The stage directions specify that ‘the fog signal is still sounding as the Curtain falls’.

‘Greenshaw’s Folly’

December 1958

Miss Marple uses her powers of observation and armchair detection to solve the brutal murder of Miss Greenshaw, owner of the monstrous Greenshaw’s Folly. In doing so she uses her knowledge of theatre, gardening – and human nature.

The history behind this short story was outlined in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks. Briefly, it was written as a replacement for the still unpublished novella ‘The Greenshore Folly’, which, in turn, had been written as a gift for the Diocesan Board of Finance in Exeter. Embarrassingly, it had proved impossible to sell the story (due, probably, to its unusual length) and Christie recalled the original and replaced it with one bearing the similar-sounding title ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’. It was published in the UK in the Daily Mail in December 1956; in the USA, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine published it in March of the following year, referring to it as Christie’s ‘newest story’.

Unusually for a short story, there are 25 pages of notes in two Notebooks. Those in Notebook 3 are alongside notes for 4.50 from Paddington, published in 1957, and The Unexpected Guest, first staged in 1958. Notebook 47 contains many of the notes for Dead Man’s Folly as well as preliminary notes for the expansion of ‘Baghdad Chest’ (as Christie refers to it) and ‘The Third Floor Flat’. The former, as ‘The Mystery of the Spanish Chest’, appeared alongside ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ in The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding but the latter was never completed.

Many themes and ideas from earlier stories make brief and partly disguised appearances in ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’. The mistress/housekeeper impersonation appeared 35 years earlier in ‘The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge’ and more recently in the 1953 novel After the Funeral. The weapon normally used from a distance but employed at close quarters featured in Death in the Clouds, the fake policeman appeared in The Mousetrap and ‘The Man in the Mist’ from Partners in Crime, and unsuspected family connections had been a constant element of Christie’s detective fiction for years. And below, we see the reappearance of an old reliable idea – that no one looks properly at a parlour maid or, in this case, a policeman.

The main plot device, as well as the choice of detective, is briefly outlined at the beginning of Notebook 3, while Notebook 47 sketches the opening pages as well as unequivocally stating the title:

Miss M

Hinges on policeman – not really a policeman – like parlourmaid one does not really look at policemen. Man (or woman) shot – householder rushes out – Policeman bending over body tells man to telephone – a colleague will be along in a moment

Greenshaw’s Folly

Conversation between Ronald [Horace] who collects monstrosities and Raymond West – photograph – Miss Greenshaw

Notebook 47 considers two possible plot developments. The first is clearly the seed of the Poirot novel The Clocks, to be written five years later. Most of the ideas noted here were incorporated into that novel apart from the reason for the presence of the clocks. ‘The Dream’ is a Poirot short story from 1938 and it contains elements of the plot of ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ – the impersonation, by the killer, of the victim and the consequent faking of the time of death.

Typist sent from agency to G’s Folly alone there – finds body – or blind woman who nearly steps on it. Clocks all an hour wrong. Why? So that they will strike 12 instead of 1.

The Dream

Wrong man interviews woman – girl gives her instruction – she goes into next room to type. Then finds apparently same woman dead – really dead before – has said secretary is out or faithful companion – faithful companion seen walking up path. Combine this with policeman – girl is typing – looks up to see police constable silhouetted against light.

The Notebooks show vacillation between Alfie and the nephew as murderer or, at least, conspirator. As can be seen, much thought and planning went into the timetable of the murder and impersonation, and this element of the plot is undoubtedly clever.

Are Mrs C. and Alfie mother and son?

Are Mrs C. and nephew mother and son?

Mrs C. and Alf do it. Get Miss G. to make will – then one of them impersonates Miss G.

A. Alfie then is seen to leave just before real policeman appears

e.g. 11.55 Alfie leaves whistling or singing

12 Alfie as policeman arrives. Fake murder – Mrs C. yells Help etc. Alfie then in pub

12.5 Alfie as policeman

B. Nephew is the one who does it. An actor in Repertory – Barrie’s plays

Alfie leaves 11.55 12 o’clock. Nephew steals in, locks doors on Lou and Mrs. C, kills Aunt, then strolls, dressed as Aunt, across garden – asks time.

Mrs C. and N[at or nephew]

12.15 – Fake murder – with Mrs C.

12.20 – Policeman

12.23 – Real police

12.25 – Nephew arrives

Alfred gets to lunch – so he is just all right – or meets pal and talks for a few minutes

Or

Mrs C. and Alfred

Fake murder Mrs C. 12.45 (Alfred in pub)

Policeman (Alfred) 12.50

Real police 12.55

Alfred returns 12.57

Nephew 1 o’clock (has been given misleading directions)

The following very orderly list has a puzzling heading; why ‘things to eliminate’? Few of them actually are eliminated; most of them remain in the finished story:

Things to eliminate

Will idea (Made with R[aymond] and H[orace] as witness) left to Mrs C. or Alfie too

Policeman idea

Alfie is nephew

Alfie Mrs C.’s son

Alfie is not nephew but pretends to be – Riding master and Mrs C.’s son)

Nephew and policeman’s uniform ( Barries’ plays)

Nephew and Alfie are the same

Mrs C. plays part of Miss G.

As we have seen, Christie toyed with alternative versions of the plot and solution before she eventually settled on one that is, sadly, far from foolproof; the mechanics of the plot do not stand up to rigorous scrutiny. Would the ‘real’ police, for example, not query the presence and identity of the first ‘policeman’, despite Miss Marple’s assertion that ‘one just accepts one more uniform as part of the law’? And we have to accept that someone would work for nothing on the basis of expectations from a will. The will itself poses more problems. The conspirators assume it leaves the money to them, either to the housekeeper, as promised, or to the nephew, as inheritance. But, in reality, the estate is left to Alfred, thereby ensnaring him in the fatal trio of means, motive and opportunity. But if the conspirators knew this they had no motive; and if they didn’t know it, framing Alfred was never a possibility.

Cat among the Pigeons

2 November 1959

As the headmistress, Miss Bulstrode, welcomes the pupils for the new term at Meadowbank School she little realises that before term ends a pupil will be kidnapped, four staff will be dead and a murderer will have been unmasked. It’s just as well that Julia Upjohn called in Hercule Poirot.

With a serialisation beginning the previous September, Cat among the Pigeons was the 1959 ‘Christie for Christmas’. It is a hugely readable mixture of domestic murder mystery and international thriller with a solution that reflects both situations. In this, the unmasking of two completely independent killers, it is a unique Christie. It was the first Poirot since 1956 and there would not be another one until The Clocks, four years later. The reader’s report on the manuscript, dated June 1959, was enthusiastic (‘highly entertaining’) rather than ecstatic (‘not a dazzling performance’). Described as having ‘enough of the crossword puzzle element towards the end to satisfy the purists, even though the solution shows that plot to be rather far-fetched’ and to be ‘more saleable than [the previous year’s title] Ordeal by Innocence’, the reader recommended including the book in a new contract. Although the reader was viewing the manuscript in purely commercial terms, few Christie aficionados would agree with the view that it would outshine Ordeal by Innocence, a far superior crime novel.

As will be seen, Christie toyed with the idea of having Miss Marple solve the murders at Meadowbank School and this might not have been such a bad idea. Miss Marple having a relative in the school is more credible than a school-girl ‘escaping’ to consult Poirot; and Meadowbank is a girls’ school. That said, Miss Marple had already had a busy decade with four major investigations, and another minor one; and she would not, perhaps, have been as adept with the international segment.

In the opening chapter there is a variation on the ploy of a character seeing something momentous – ‘“Why!” exclaimed Mrs Upjohn, still gazing out of the window, “how extraordinary!”’ – that has an important bearing on subsequent events. This has often taken the form of seeing something over the shoulder of another character, as do Lawrence Cavendish in the bedroom of the dying Mrs Inglethorp in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Mrs Boynton in the hotel foyer in Appointment with Death and Satipy on the path from the tomb in Death Comes as the End. In each case a death soon follows and the unidentified sight forms part of the explanation. If Miss Bulstrode had been listening properly to Mrs Upjohn, much of the ensuing mayhem might have been avoided. Two further telling examples of this ploy would appear within the next five years: when Marina Gregg, in The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side, looks down her own staircase and sees something that transfixes her, and when the unfortunate Major Palgrave, in A Caribbean Mystery, recognises a killer over Miss Marple’s shoulder, just before his own murder. As with other novels from Christie’s later period – Hickory Dickory Dock, 4.50 from Paddington, Ordeal by Innocence, The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side – there is an unnecessary and ‘rushed’ murder in the closing stages. It features the future victim talking to an unseen, and unnamed, killer, also a feature of Hickory Dickory Dock.

There are over 80 pages of notes devoted to Cat among the Pigeons in three Notebooks, 70 of them in Notebook 15. The intricacy of the plot, with an unusually large cast of characters, two separate plot strands and scenes set in Ramat and Anatolia, as well as some beyond the grounds of Meadowbank, account for these extensive notes.

The first page of Notebook 15 is headed ‘Oct. 1958 Projects’, and goes on to list the ideas that would become The Pale Horse, Passenger to Frankfurt and Fiddlers Five/Three, along with the possibility of plays based on either Murder is Easy (or, as it appears in the Notebook, ‘Murder Made Easy’) or ‘The Cretan Bull’, from The Labours of Hercules. Idea C on this list became Cat among the Pigeons.

The earliest notes show Christie considering basic possibilities, which detective to use and how they might be brought into the story. At this stage also the princess/schoolgirl impersonation is under consideration, carrying echoes of a similar plot device in ‘The Regatta Mystery’.

Book

Girl’s school? Miss Bulstrode (Principal)

Mrs. Upjohn – or parent – rather like Mrs. Summerhayes in Mrs. McGinty, fluffy, vague but surprisingly shrewd

Miss Marple? Great niece at the school?

Poirot? Mrs. U sits opposite him in a train?

Someone shot or stalked at school sports?

Princess Maynasita there or an actress as pupil or an actress as games mistress

There were two contenders for the book’s title. The rejected one, which is not at all bad, is briefly mentioned at the start of Chapter 8 when the two policemen first hear of the murder:

Death of a Games Mistress

Cat among the Pigeons

A list of characters in Notebook 15 is remarkably similar to those in the published novel, although the number of characters would increase considerably:

Possible characters

Bob Rawlinson

Mrs. Sutcliffe (his sister)

Frances [Jennifer] Sutcliffe (her daughter)

Angele Black

Fenella (pupil at school)

Mademoiselle Amelie Blanche

Miss Bolsover [Bulstrode] Principal of School ‘Meadowbank’

Miss Springer – Gym Mistress

Mrs. Upjohn (rather like Mrs. Summerhayes)

Julia Upjohn

Mr Robinson

It seems likely that Angele Black and Amelie Blanche were amalgamated into Angele Blanche. It would seem that the character ‘Fenella’ was originally intended to be another agent, but masquerading as a pupil, possibly as well as Ann Shapland, within the school. The comparison of Mrs Upjohn with Maureen Summerhayes refers to Poirot’s inefficient landlady in his disreputable guest house in Mrs McGinty’s Dead, and it is an apt one. Both are disorganised, voluble and immensely likeable; and each is the possessor of a valuable piece of information which imperils their safety.

The set-up on the opening day of the new term is sketched, including the all-important Mrs Upjohn and her sighting, although at this stage what, or more strictly, whom she sees is still undecided:

Likely opening gambit

First day of summer term – mothers etc. – Mrs. U sees someone out of window. Could be New Mistress? Domestic Staff? Pupil? Parent?

The letters that constitute Chapter 5, and that contain much that is later significant, are considered in Notebook 15:

Letters

Julia

Jennifer

Angele Blanche

Chaddy

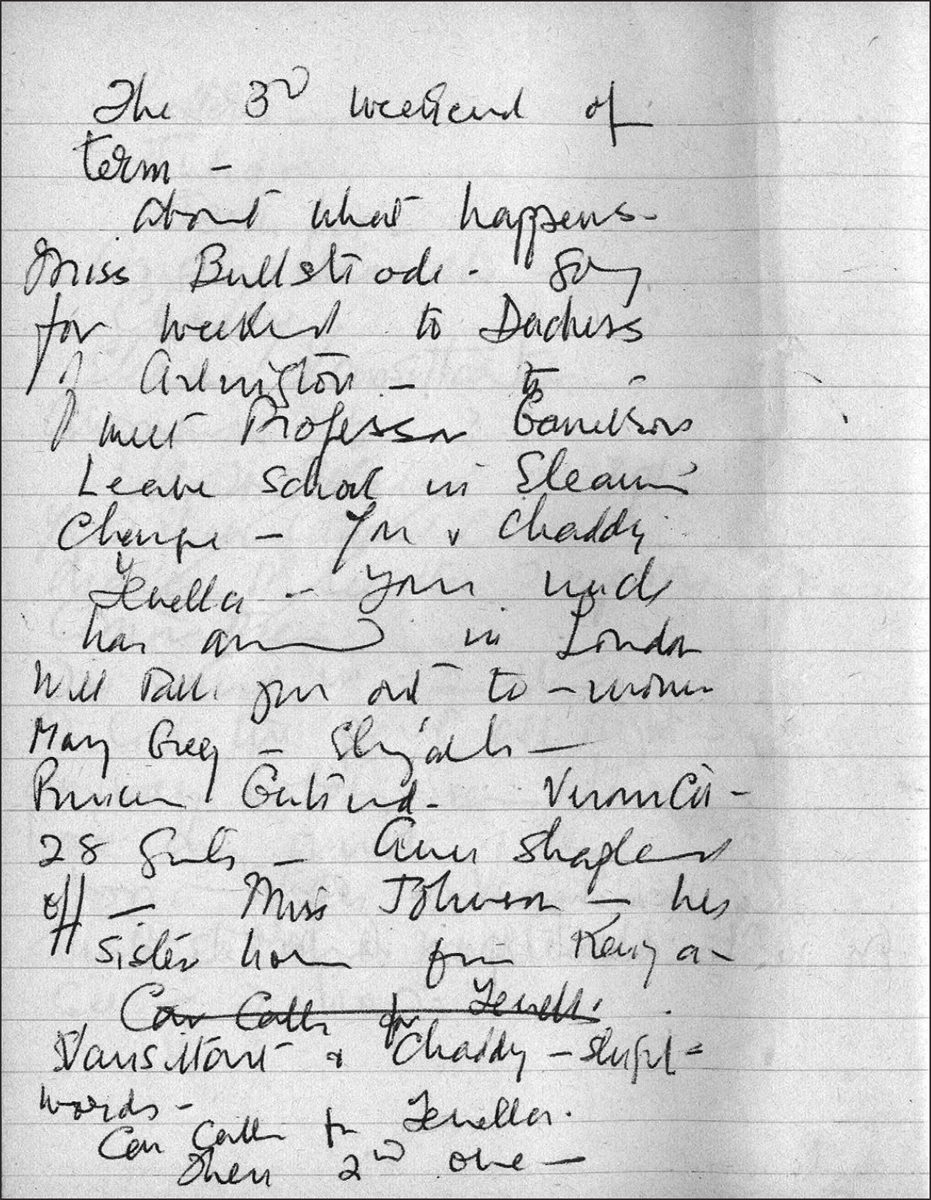

Two pages from Notebook 15 with a lot of plotting and speculation for Cat among the Pigeons. Note the incorrect spelling of Miss ‘Bullstrode’.

Eleanor Vanstittart

Anonymous to ??

Well, I’ve settled in all right – you’d have laughed like a drain to see the reception committee. I’ve settled in – in this I look the part all right. Anyway, nobody seems to have any doubts of my bona fides – then we shall see what we shall see – I hope!

The letter from Miss Chadwick (‘Chaddy’) did not materialise and although there is an anonymous one it is clear to the reader that the writer is Adam, the gardener. The inclusion of the one sketched here would have been tantalisingly mysterious and it is a shame that it was never developed.

Christie devotes a lot of space to the progress of the tennis racquet:

History of Racquet

A. Brought home by Mrs. Sutcliffe by sea (Does she see A[ngele] B[lanche] at Tilbury?)

B. Her husband meets her – drives them straight down to country or they go down by train and it is left in train?

C. House is entered – tennis racquets taken and a few other things, later recovered by police

In effect, it is this unlikely object that sets the plot in motion. In this, it has echoes of the ninth Labour of Hercules, ‘The Girdle of Hippolita’, where Poirot investigates the disappearance of the schoolgirl Winnie King; she also was the unwitting smuggler of contraband in her otherwise innocent luggage. The initial swapping of the tennis racquets is acceptable but the scene in Chapter 12 ii, when a total stranger approaches Jennifer and asks to exchange them (again), is less than convincing. Christie considers possibilities, discarding those such as the use of a lacrosse stick; note also her practical concerns about how long lost property offices retain items: