Chapter 10

The Fifth Decade 1960–1969

‘After all, to be able to continue writing at the age of 75 is very fortunate.’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

After the Funeral • The Clocks • Endless Night • Lord Edgware Dies • Third Girl • Three Act Tragedy • ‘‘Witness for the Prosecution’

As she entered her fifth decade of crime writing Agatha Christie continued experimenting with her chosen genre. The decade began inauspiciously with a collection of short stories, the title story of which, ‘The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding’, was a reworking of a 1923 Poirot case, ‘A Christmas Adventure’; but the elaboration, unlike similar earlier experiments, added only words. ‘The Mystery of the Spanish Chest’, in the same collection, was a far more imaginative expansion of the earlier ‘The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest’. In fact, at one point the collection was to be called The Mystery of the Spanish Chest and other stories.

Of the ten titles she produced in the 1960s only two are pure whodunits, the last examples of the genre that she was to write. The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side (1962) and A Caribbean Mystery (1964), both Miss Marple novels, employ clever variations on a plot device she had used before, that of a character seeing something surprising, shocking or frightening over someone’s shoulder. The other Marple novel of the 1960s was At Bertram’s Hotel (1965), a nostalgic journey into the past for the elderly Marple and Christie, with a not wholly believable variation on yet another earlier plot device. Though all three Poirot novels of this decade are disappointing – the Christie magic is missing from the development of each one – the fundamental plot ideas are as inventive as ever: in The Clocks (1963), a stranger’s body found in a room full of incorrect clocks; in Third Girl (1966), a girl who thinks she ‘may’ have committed a murder; and in Hallowe’en Party (1969), a child is drowned while bobbing for apples. The best novels of this decade were, ironically, the two non-series titles, The Pale Horse (1961) and Endless Night (1967). Both of them were innovative, experimental and sinister – black magic murder to order in the former and a wholly original reworking of the Ackroyd trick in the latter – each showing an aspect of the Queen of Crime not heretofore seen.

Some old friends make welcome reappearances. Mrs Oliver has a solo run in The Pale Horse, which affords us a glimpse into the creative process of a mystery writer and, perhaps, into that of her creator; and appears with her old friend Poirot in both Third Girl and Hallowe’en Party. Tommy and Tuppence solve their penultimate case in By the Pricking of my Thumbs (1968). Age has not withered their spirit of adventure and the case they investigate, the disappearance of an elderly lady from a retirement home, is dark and sinister.

The elderly Christie is reflected in many of the books of this decade. Poirot’s appearance in The Clocks is almost a cameo as he emulates an armchair detective and reflects on his magnum opus, a study of detective fiction; and in Third Girl he does unconvincing battle with the London of the Swinging Sixties. Miss Marple has aged since her previous appearance and agrees to a live-in companion in The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side. Tommy and Tuppence are middle-aged grandparents and most of the characters in By the Pricking of my Thumbs are similarly elderly. And this book, as well as Hallowe’en Party and At Bertram’s Hotel, is a journey into the past.

While The Mousetrap continued its inexorable success story with another new record in 1962 (the longest running play in London), Christie’s only new play of this decade was another experiment. Rule of Three (1962) consists of three one-act plays, each totally different in style and content. Two years earlier saw a dramatisation of Five Little Pigs as Go Back for Murder, but both offerings received a cool critical reception.

In the cinema the four Margaret Rutherford Marple films were released – or should that be ‘escaped’? – much to Christie’s horror; only one, Murder She Said, was based on an authentic Marple novel, 4.50 from Paddington. Of the other three, two were based on Poirot novels and one was a completely original script; and in all of them Miss Marple is unrecognisable, literally and metaphorically, as the elderly denizen of St Mary Mead. As a direct result, the 1964 Marple novel, A Caribbean Mystery, carried on its title page the reclamation ‘Featuring the original character as created by Agatha Christie.’ The following year, 1965, found Ten Little Indians transposed from an island off the coast of Devon to an Austrian ski resort (but filmed in Dublin!), but with the innovation of The Whodunit Break – a ticking clock-face reprised the suspects and murders for one minute to help the audience decide on the villain. The Alphabet Murders appeared in 1966, bearing almost no similarity to its inspiration, The A.B.C. Murders, to the extent of including a cameo appearance from Miss Marple. (All five films came from the same production company.) A more faithful adaptation was the 1960 screen version of Spider’s Web, from the play of the same name. Also in the world of cinema, Christie worked on an adaptation of the Dickens novel Bleak House, but although she produced a script (‘I quite realise that a third or more of the present script will have to go’) in May 1962 the film was never made. And Hercule Poirot debuted on US television in The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim in 1962.

In 1965 Christie published Star over Bethlehem, a miscellany of Christmas poetry and short tales, and in October of that year she finished work on her Autobiography. This was a project she had worked at, on and off, for the previous 15 years and although the book would not be published until after her death she enjoyed reviewing her life; it fell to her daughter, Rosalind, to edit the vast amount of material to produce the 1977 book. As we know from the recent release of recordings of the ‘writing’ of her Autobiography, Agatha Christie used a Dictaphone for many years. It is difficult to say with any certainty when this practice began, but in a radio interview as early as 1955 she said, ‘I type my own drafts on an ancient faithful machine I’ve owned for years. And I find a Dictaphone useful for short stories or for re-casting an act of a play, but not for the more complicated business of working out a novel.’ The implication is that she was practised in the use of the machine; and, of course, as far back as 1926, her most infamous title, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, featured that piece of equipment as a plot device.

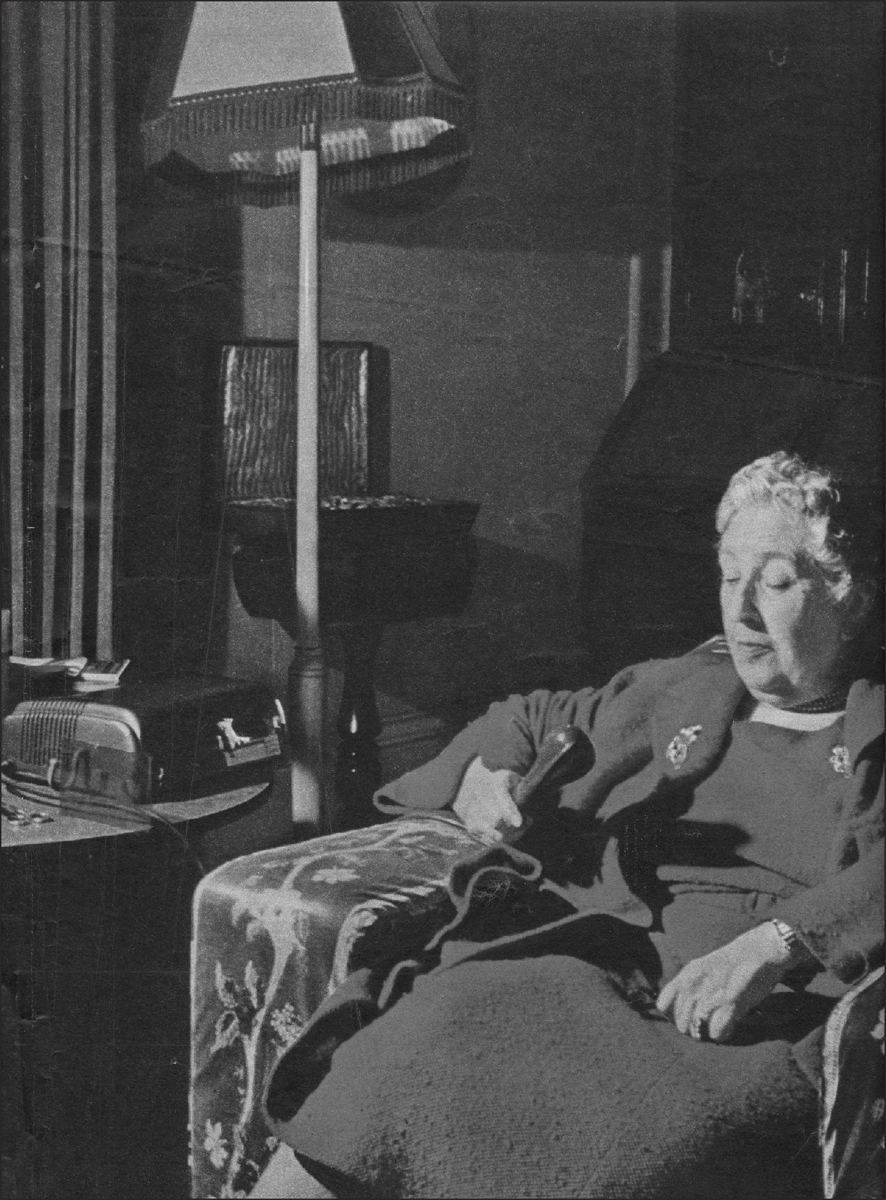

The photograph showing Agatha Christie with the Dicta-phone dates from the late 1950s. The resultant tapes, or to use the more accurate term, Dictabelts, still exist for many of the titles from the succeeding decades. By that stage, no doubt, the elderly Christie found it physically easier to sit in her chair and ‘speak’ her novels into a machine and then correct a draft typed by her secretary. The less detailed notes for the last half-dozen novels can be seen as reflecting this procedure. The exhaustive plot experimentation and variations-on-a-theme of the Notebooks of yesteryear are replaced by plot highlights which she considered sufficient for this method of writing. This procedure meant that the later novels were both more verbose in narration and less tight in construction than the earlier, more compactly written books; to echo her own words, the Dictaphone was not suitable ‘for the complicated business’ of constructing a detective novel.

Agatha Christie, photographed in Winterbrook House in the 1950s, using a Dictaphone.

In 1967 she co-operated with the first book to be written about her work, G.C. Ramsey’s Agatha Christie: Mistress of Mystery. Although a slight book viewed from today’s standpoint, it was the first to impose order on the chaos of title changes, both transatlantic and domestic, and variations in short-story collections; thus it was as welcome to Christie’s agent and publisher as it was to her fans. And it remains the only book about Christie which received her personal cooperation. In 1961 she received a doctorate from Exeter University, where today an archive of her papers is held. That was also the year in which Christie was declared by UNESCO to be the world’s best-selling writer.

The Clocks

7 November 1963

A roomful of clocks showing the wrong time, a blind woman, a dead man and a hysterical girl – when Colin Lamb explains the story to his friend, Hercule Poirot decides that the situation is so bizarre that the explanation must be simple. Developments prove otherwise.

Appearing between two very typical Miss Marple whodunits – preceded by The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side and followed by A Caribbean Mystery – The Clocks was the first Poirot novel since Cat among the Pigeons in 1959. Poirot appears in only three chapters and acts, literally, as an armchair detective, with Colin Lamb bringing him the information to enable them both to arrive at a conclusion.

The Clocks is an uneasy mix of spy story and domestic murder mystery with little in the way of clues to help the reader distinguish between the two. There are, as usual, clever ideas – the telephone call and the broken shoe, the adoption of a ready-made plot, the conversion of secrets to Braille – but the overall explanation is a disappointment. If the spy angle had been dropped and the inheritance plot elaborated the result would have been a tighter book. And, as she has done in many previous titles, Christie introduces an unsuspected and unnecessary relationship in the closing chapters.

A fascinating interlude with Poirot occurs in Chapter 14 when we read of his forthcoming study of detective fiction. He mentions several milestones of the genre: The Leavenworth Case, The Adventures of Arsene Lupin, The Mystery of the Yellow Room, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. He goes on to discuss a number of authors, some of whom, although fictional, are identifiable – Cyril Quain with his attention to detail and unbreakable alibis is Freeman Wills Crofts; Louisa O’Malley with her milieu of brownstone mansion in New York is Elizabeth Daly. Florence Elks is more difficult to identify but is perhaps Margaret Millar, a writer Christie admired, as she stated in an interview in 1974. A Canadian who set most of her novels in the USA, Millar has order, method and wit, although not the abundance of drink to which Poirot refers. Two other writers are mentioned but both are firmly fictional – Garry Gregson, who is an important element in the plot of The Clocks, and, of course, Mrs Oliver.

The other area for speculation is the parentage of Colin Lamb. When they meet, Poirot asks after Colin’s father and wonders why he is not using the family name. In G.C. Ramsay’s Mistress of Mystery (1967) Christie is quoted as confirming that Colin is Superintendent Battle’s son.

In Notebook 4, on a page dated 1961, an alphabetical list of plot ideas includes the inspirations for The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side and A Caribbean Mystery; on that list idea F is a brief outline of The Clocks. And a year later the tentative title appears on a listing of future books.

F. The Clock – as beginning – typist – dead body – blind old lady

1962

Notes for 3 books

Y. The Clocks (?)

Z. Carribean [sic] Mystery

X. Gypsy’s Acre

But in fact the plot for The Clocks goes back a lot further than that. In late 1949 Agatha Christie set a competition for which she wrote the opening of a short story that competitors were asked to complete. It concerned a typist, Nancy, arriving at a house and letting herself in to the front room. There she finds a collection of clocks, a dead man and a blind woman. Twelve years later Christie herself resurrected the story and set about expanding it. The main difference between the two is that the clocks in the short story all show different, and wrong, times whereas the clocks of the novel all show the same, but equally wrong, time. Unsurprisingly the character names are also different, as is the street address; but the similarities are striking – the description of the clocks is identical and the ‘Rosemary’ clock is specifically mentioned; the telephone call making the appointment is a mystery and the blind woman, it transpires, is Nancy’s mother. Overall the explanation of the presence of the clocks is more convincing in the prize-winning solution than in the novel.

In its earlier incarnation the short story is called ‘The Clock Stops’; this is also the title used in Notebook 8 where most of the plotting, about 50 pages, is contained. A list of possible characters, most of whose names will change, and a possible motive, are the first considerations:

Mildred Pebmarsh – fiftyish – blind – had been a librarian – now teaches Braille

Alice Dale – young stenographer (Is her second name Rosemary) Does Alice, flying out of house, collide with Colin

Dead Man

Miss Curtis Head of typing firm

Colin Lamb – young man – journalist? Doctor? Investigator? On vacation

Christie sketches the motive scenario more than once. Elements of each sketch were used in the final version, which has much in common – an unexpected arrival from abroad endangering a criminal impersonation – with Dead Man’s Folly:

Money involved – something with money (gain)

A middle aged woman inherits vast fortune from an uncle in Canada? (Advertised?) S. America? (or written to Mrs. Bristow?) Actually real Mrs. Bristow is dead and Bristow has remarried (or not?). He decides that he and his wife will claim – was he small builder? Bankrupt – settled in her place. Anyway no one knows he has a first wife. But senior partner of firm of solicitors knows real Mrs. B. So he comes down to (No. 6? 19?) is received, drugged and killed. Taken across diagonal to No. 19 – 61?

Unsatisfactory person marries nice girl – goes abroad – actually she dies and he marries again – a woman who was sec[retary] to det. story writer – his wife poisoned but he won’t marry her. Fortune left her – she plays invalid. Papers brought for her to sign – O.K. Later someone who knows her well comes – they prepare – plot hers – (from favourite employer) her name is Rosemary – uses old clock. Is girl’s name Alice Rosemary called after his mother? Mother is dead – some mystery about her. A. is illegitimate

Further elaboration follows; the first possible explanation of the clocks is (thankfully) discarded and the second one adopted:

Point of various things

(1) Clocks – the time (Fast?) (Slow?) 3–25

Possibly – Rosemary faded carriage clock – press 3 – 2 – 5 contains a secret compartment – clocks works have been taken out (a reference to time of a murder – it took place on a Saturday night in Oct. (daylight saving!)

(2) Rosemary – the name of someone connected with Martindale – Alice or M. Pebmarsh

The whole is a plot – invented by Rosemary Western (a Mrs. Oliver) now dead and adapted for use as camouflage by her secretary who is – Martindale? Pebmarsh? Mrs. Bristow at No. 61 Pam or Geraldine

Fortune left to Mrs X (Argentine? Australia? S. Africa?). Actually she has died abroad and husband remarried almost at once. Only one person knows Mrs X by sight. It is this member of law firm who has come over. They plan murder – but not to let him be identified. Elaboration and clocks etc. is suggested by plot of an unpublished book. Mrs X or Miss Martindale was private secretary to a Creasey detective story writer.

The reference to ‘a Creasey detective story writer’ is unexpected. John Creasey was a hugely prolific writer – producing over 500 titles under a variety of pen names – of most types of crime novel, with the exception of detective stories. In Chapter 28 Poirot explains the original meaning of the clocks as they feature in the unpublished manuscript; it was a code to the combination to the safe, concealed behind a reproduction of the Mona Lisa, containing the jewels of the Russian royal family. He describes the plot as ‘Un tas de bêtises, the whole thing’, in other words, nonsense.

The all-important story of Edna and her damaged shoe appears alongside the timetable for the fateful lunch-hour:

Edna in outer office with stiletto heel that has come off – describing where and how she bought buns and came back to office

Timing here to be consistent

1.30 – 2.30 Alice lunch interval

12.30 – 1.30 L[unch] interval for ?

Edna leaves office 12.30 o’clock – returns by

12.50 – no call comes through before 1.30

1.30 Miss M goes out

or

Edna goes out 1.30 – back 1.50 – better

No call before 2.30

Miss M goes out 12.30 – 1.30

Christie experimented throughout the Notebook with various neighbours, some of whom made it into the novel. Aspects of the following jottings – ‘quiet gardening type’, ‘Cat lover woman’, and the children – appear, but adapted and rearranged. Interestingly, the ‘secretary to a bestseller writer’ becomes a major plot feature; but the character chosen for this important role is not a resident of Wilbraham Crescent. Despite the alteration of house numbers between Notebook and novel, and the cryptic illustration in Chapter 6, these are not important elements. The use of a Crescent is a useful, though not entirely convincing, method of isolating the suspects:

A sketch from Notebook 8 during the plotting of The Clocks. Christie was experimenting with a combination of the numerals from a clock-face and a possible sketch of Wilbraham Crescent.

Neighbours

No. 60 Man wife children – man sporty talkative, wife v. quiet

62 Couple of women – Pam and Geraldine – develop their characters

No. 18 Mainly cats?

No. 19 Middle aged man – a gardener – invalid wife? Got a blind spinster sister

Where is my murder and why

(1) Quiet gardener man – carries victim in sack

(2) One of the two women – Geraldine? – has been secretary to a bestseller writer (Mrs. O?!!) – has taken various details from one of her discarded plots

(3) Heart man with wife and children

(4) Miss Pebmarsh

Neighbours

16. Cat lover woman with draperies, accusative of one of the others (? which) because he killed my cat [Mrs Hemming at No. 20]

20. 2/3? awful children (later one of them says something) like B.B.’s children 10, 7, 3? Harassed fond mother children like Miss P [the Ramsays]

61. Mr. Bland – unimaginative man, sandy hair, freckled, commonplace – builder in small way near bankrupt – then wife comes into money. Thinking of living abroad – the wife would like it – I don’t know myself – can’t get any decent food abroad [no. 69]

62. 2 women? One former secretary to thriller writer or young man living with mother. He is weakly looking – she is really a man? Arty husband and wife – a son Thomas

69 60. Middle-aged man – quiet gardening type – went with wheelbarrow sacks etc. [Mr McNaughton] Could have a flirty spinster sister

One of the problems with the book, though, is that there are too many neighbours and that they are not clearly enough delineated to fix them in the mind, while the lengthy interviews with them offer little in the way of information, either for the police or the reader.

Christie also toyed with ideas that were not pursued in the finished novel, but some of which were to be used at a later stage. The first has an element of the plot of the next Poirot novel, Third Girl, where a female character has two distinct ‘lives’ miles apart, the family of each unaware of the existence of the other:

Clocks

Miss Pebmarsh – forty? fifty? blind – who is she?

Idea – Really a Miss or Mrs X has a well authenticated life in small town Torquay or Wallingford; companion lives with her or perhaps she has a room as P[aying] G[uest] in people’s house – goes away occasionally to stay with relations – ‘Universal Aunt’ sees her across London. Returns in due course – says she is a missionary – sister of a missionary. Came home with ill health – there was such a person – but lost track of.

And, as can be seen below, another early possibility was to combine the ‘Greenshaw’s Folly’ idea with The Clocks; in the short story a secretary does indeed go to Greenshaw’s Folly to begin work:

Typist sent from agency to G’s Folly alone there – finds body – or blind woman who nearly steps on it. Clocks all an hour wrong Why? So that they will strike 12 instead of 1

Further ideas followed, some of which – the ‘thriller’ plot, the claimed husband, the postcards from abroad – found their way into the book:

Man next door does murder of blackmailer. Takes advantage of Miss P’s blindness – kills man with dagger? Or strangles? – carries him in through window – then rings up typewriting agency. Some reason for asking for that particular girl? Is her name Rosemary – clocks just a fancy touch (obvious really – contrived) mistake – one clock is at a quarter to nine

A ‘thriller’ plot – some secret process – man almost gets it – is killed – scrawls a few words – 61 – L

A woman whose lover is murdered

” ” daughter ” A 14

” ” son ” (revenge)

Idea put about is that a woman Mrs U meets Mr C at hotel – is to take him down in car. Later she calls for baggage – goes to Victoria . . . and travels with man like him (passport?) latter sends p.cs from abroad or his luggage is in hotel unclaimed. Mr C at Cresc. is killed . . . taken across to 19 – Mr Curry – later woman will turn up and claim him as husband. Mr C disappears

Vasall like – plans photographed during [lunch?] hour – 2 overcoats alike? – or bus or train. Miss Pebmarsh – (caraway seed? aniseed?) Found by agent – or agent writes it as dying

This last outline is very cryptic. ‘Vasall’ is a reference to the real-life spy John Vassall, a British civil servant who was arrested as a spy in September 1962 and subsequently convicted. This would have been a high-profile event during the genesis of The Clocks. The ‘2 overcoats’ is probably a ploy used to effect a quick change of appearance in order to avoid detection; the bus/train possibility is probably another escape route plan. The caraway seed/aniseed reference is probably to the hoary old plot device of using either as a means of tracking a quarry, a variation of which is used in the denouement of N or M?

The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side, published the previous year, and A Caribbean Mystery, the following year were the last ‘pure’ whodunits Christie was to write but The Clocks, despite its promising opening, remains an inexplicably disappointing offering.

Third Girl

14 November 1966

When ‘third girl’ Norma Restarick approaches Poirot with a story of ‘a murder that she might have committed’, he is intrigued. When she disappears, and a murder is committed at her apartment block and his friend Mrs Oliver is coshed, Poirot enters the unfamiliar world of Swinging Sixties London.

Having made little more than a cameo appearance in his previous case, The Clocks, Poirot tackles old problems in a new setting in Third Girl and this time his involvement is more active. Like some other novels from Christie’s last decade, Third Girl is wordy; there are many passages, and indeed chapters, which could, and arguably should, have been omitted, such as the detailed description of Long Basing (Chapter 4) and much of Mrs Oliver’s trudge around London (Chapter 9). The plot itself, despite its promising beginning, requires a considerable suspension of disbelief, while the Swinging Sixties background is largely unconvincing. The impersonation disclosed in the final explanation is difficult to accept, calling into question the entire basis of the novel. Third Girl is the weakest book of the 1960s.

This uncertainty is mirrored in the notes. They are scattered over six Notebooks and 90 pages but they are repetitive, unlike the Christie of yesteryear. There are nevertheless ideas that she considered but ultimately rejected, although, as we shall see, some of them were utilised, three years later, in Hallowe’en Party.

When we meet Poirot in the opening chapter he has just completed his magnum opus on detective fiction, a project on which he had previously been working during The Clocks. Mrs Oliver makes her second appearance of the decade having already featured, sans Poirot, in The Pale Horse. She would appear again in Hallowe’en Party and for the last time in Elephants Can Remember. It can be no coincidence that Mrs Oliver, and the now very elderly Miss Marple, both characters with which Dame Agatha had now much in common, appear in over half of the last dozen novels.

A major element of the plot of Third Girl concerns the drugging of Norma Restarick. This has echoes of A Caribbean Mystery when Miss Marple discovered that Molly Kendal was the victim of a similar plot; and 25 years earlier the poisoning of Hugh Chandler in ‘The Cretan Bull’, the seventh Labour of Hercules, is undertaken for a similar sinister reason.

Mr Goby from After the Funeral makes a brief appearance. And is Chief Inspector Neele the same policeman, though not of the same rank, who investigated, alongside Miss Marple, the deaths at Yewtree Lodge in A Pocket Full of Rye? Is Dr Stillingfleet, moreover, the medical man who featured in ‘The Dream’?

The intriguing opening scene is sketched over half a dozen times, with little variation, in four separate Notebooks. This premise would seem to have been the starting point of the novel and the one unalterable idea throughout the notes.

Poirot breakfast – Girl – Louise – I may have committed a murder. 3 girls in a flat Louise and Veronica – Judy – (Claudia Norma Townsend). One of these three girls. What does she mean by ‘she thinks she may have committed’

Poirot at breakfast – girl calls ‘She thinks she may have committed a murder.’ ‘Thinks’ Doesn’t she know? No clearness – no precision. ‘I’m sorry – I shouldn’t have told you – you’re too old’

Poirot at breakfast table – Norma (an unattractive Ophelia) says she may have committed a murder – then tells Poirot he is ‘too old.’

Suggestions – Chap I – P. at breakfast

Poirot at the breakfast table – thinks she may have committed a murder. Disappointed by P – too old – recommended by Mrs. Oliver – makes excuse – goes. Poirot worried

Idea A July – 1965

Poirot at his breakfast table (The Late Mrs. Dane). P. at breakfast – George40 announces – a – pause – young lady. I do not see people at this hour. She says she thinks she may have committed a murder. ‘Thinks? It is not a subject on which one should be in doubt.’ Girl – unkempt – Poirot regards her with pain etc. G[eorge] and P discuss – neurotic?

This last sketch merits discussion. It appears in Notebook 27 a page after the final notes for At Bertram’s Hotel, the previous year’s book. To judge by the date heading this note, Christie was mulling over ideas for her 1966 book having just despatched the 1965 Christie for Christmas to Collins. In the notes that follow we find, using an alphabetical sequence, the germs of Endless Night, Nemesis and Hallowe’en Party.

Idea B, four pages later, is ‘Gypsy’s Acre – place where accidents always happen’ (this became Endless Night). Idea C is a variation on ‘The Cornish Mystery’, though it did not generate a subsequent novel: ‘Wife thinks her husband is poisoning her . . . niece’s young man writes love letters to her – but to Aunt also’. Idea D toys with the possibility of a ‘National Trust Tour of Gardens’, later developed into Nemesis. And Idea E, headed ‘Mary, Mary, Quite contrary’, concerns a foreign girl who is left everything in the will of her wealthy employer. Christie urges herself at the end of this note, ‘Good idea – needs working on’; after further work this became Hallowe’en Party.

The other interesting point concerns the reference to ‘The Late Mrs. Dane’. The first page of Notebook 19, during the planning of what was to become Sleeping Murder, is headed:

Cover Her Face

The Late Mrs. Dane

They Do It with Mirrors

The promising title ‘The Late Mrs Dane’ was not pursued although the name itself appears in the early sketches for Sad Cypress and The A.B.C. Murders. Thirty years later, in 1965, we can see that the elderly Christie was still toying with it; and it is a great title.

Mrs Oliver’s visits to Borodene Mansions in Chapters 3 and 7, and Poirot’s to High Basing in Chapters 4 and 5, are sketched thoroughly in Notebook 26:

Mrs Oliver visits Borodene Court – a flat – 3 girls

Claudia – confident, efficient good background

Frances – Arts Council or Art Gallery.

Norma

Milkman mentions to Mrs O. Lady pitched herself down from 7th floor. Mind disturbed – had only been in flat a month

Decoration of flat – all similar built-in furniture and wallpaper – one wall with huge Harlequin

Poirot at High Basing – visits Restaricks – pretends to know Sir Rodney. On leaving has a snoop before he and Mary encounter the Peacock (David) also snoopy. Later Poirot gives lift to David

And the essence of the plot is captured in the following paragraph from Notebook 42:

Frances in an art racket – David works with her – gallery ‘in’ it. She runs picture shows abroad – he forges pictures. She meets McNaughton, he and Restarick whose brother dies suddenly – he takes R’s place – R’s passport faked by her. She goes back to England – once there assumes part of Mary – blonde and wig – Mrs Restarick – visit Uncle Rodney – furniture in store – picture ‘cleaned’ – substitute painted by David of McNaughton. Katrina found by Mary – dailies – Mary up and down to London, Frances to Manchester – Liverpool – Birmingham etc. Frances gets Norma to Borodene Court – she seldom sees F – but thinks she is going mad because she dreams F is M

Most of the salient points of the plot are covered but the words ‘assumes part of Mary’ are easier to read than to imagine. They involve a character playing a continuing dual role. It is difficult for the reader to believe that, even in Norma’s drug-induced twilight existence, the same person could have been accepted as her flatmate and her stepmother. Impersonation has frequently played an important part in Christie’s fiction – Carlotta Adams in Lord Edgware Dies, Sir Charles Cartwright in Three Act Tragedy, Miss Gilchrist in After the Funeral, Romaine in ‘Witness for the Prosecution’ – but in each of these cases the impersonation is a one-off episode and not a long-term arrangement. And in three of these instances the impersonator is a professional actor.

The sequence of events in Chapter 22 is outlined in Notebook 42:

Frances speaks to porter, goes up in lift – inserts key etc. Hand rises slowly to throat – sees herself in glass – her look of frozen terror. Then screams and runs out of flat – grips someone – killed – she has just returned from Manchester? Dead body – 2 hours dead. F. comes by train from Bournemouth? – changes to Mary – meets David – where are Claudia? Andrew? Mary?

And there are flashes of Christie’s old ingenuity – the odd/even numbers, the different/same room scenario – in this extract from Notebook 49; elements of this note surfaced in the book although the practicality of the idea is questionable. The reference to ‘Swan Court’ is to the actual apartment block in which Christie had a flat for much of her life:

An idea

Girl or (dupe of some kind) taken to flat – go up in lift – one of kind you can’t see or count floors. Room has very noticeable wall paper – Versailles? Cherries? Birds? She swears to this – believing it – describes it minutely. Actually that room and wallpaper is somewhere else. Wallpaper is put on same night – it is all prepared – cut etc. – pasted on – would take a couple of hours not more – but it would have to dry off and therefore would be described as a damp room – ‘had patches’ of damp on it or a room with the noticeable paper would be papered over with another paper. The similarity of rooms in a block like Swan Court in, say, opposite sides of building – odd and even numbers if some flats furniture would be the same

Much of the detail explored in the following extract from Notebook 50 was to change but some concepts – the drugging and scapegoating, the fake portrait and the subterfuge with regard to flat numbers – remained:

Girl doped by other girls (Claudia? Frances?) friends hears a shot – comes to find herself shooting out of window – other girl supporting her and pistol really discharged by her – Lance they get in and fix him up – bandages etc. He and (Cl?) (Frances?) are ‘in it’ together against simple Norma. Later she is again ‘doped’ a second brain storm – result – a young artist is shot – girls give evidence for Norma – police can’t shake them but don’t believe them.

(B)? The Picture by Levenheim A.R.A. is of her mother Lady Roche in country house. Actually picture is copied by young David McDonald – only face of (Mary?) is substituted – then David is shot. Norma suspected and believes herself she did it. Thought to be a sexy crime.

C. Or is Arthur Wells – Mary’s husband – painted into picture

D. Or Arthur and Mary – Sir R – can’t see A very well but believes he is his nephew. A man with a stroke – is bribed to impersonate Arthur at a specialist.

[E] Painting – a Lowenstein – (L is dead) worth £40,000 – insured. Copy false – seen on one evening – party

Points of interest

Double flat – 71 7th floor (faces W), 64 6th floor (faces E) Police called to which?

Finally, in the following extracts, all from Notebook 51, there are glimpses of the Christie of yesteryear with the listing of ideas and the consideration of possible combinations of conspirators (throughout these sketches the David of the book appears as Paul):

Norma – are her words connected with home – stepmother? Her own mother – Sonia – old boy?

Or

3rd girl activities – is boy friend (Paul) a Mod – like a Van Dyk [sic] – brocade waistcoat – long glossy hair – is he the evil genius – is he in it with Claudia? with Frances? Narcotics?

Does Norma get keen on him – she acts as a go between for them? A girl – an addict – dies really because she is found to be a police agent getting evidence – killed by Paul or Claudia – (Frances) – they make Norma believe that she brought her an over strength dose of purple [hearts] (some new name) Technically she might be accused of murder – they do this to get her finished and say they will protect her – she really is fall guy if necessary – she thinks of getting help from Poirot – they decide she is danger – they’ll get rid of her. What is Norma’s job? Cosmetics Lucie Long powders etc. N[orma] packs things

2nd idea

Paul is really police spy – he tangles with the girls

3rd idea

Paul is in it with Sonia

4th idea

Paul is in it with Mary Wells. Sir Rodney – rich – his nephew and wife come to live – or his niece and her husband. Niece dies – widower is married – 2nd wife sucks up to old man – then Sonia arrives also sucks up to him – he alters his will

5th idea

Sonia and Sir Paul linked together – he is impersonating real Sir R

6th idea

Mary Restarick – her beautiful blue eyes – tells Poirot how she got Norma to leave home – better for her – because she hates me. Shows Poirot a chemist’s analysis – arsenic? Or morphia. Norma says – I hate her – I hate her – does boy friend old boy dies see her (he says) walking in sleep – puts something in glass. He tells her – will of old Rodney forged – by Norma?

7th

Poirot and Mary – her beauty – blue eyes – about Norma – glad she went – I didn’t know what to do – takes from locked drawer an analyst’s report – Arsenic? Or morphia? – hated me because of her mother

Sadly Christie’s former ingenuity is missing from these scenarios (note, for example, that Ideas 6 and 7 are very similar). Even if some of the ideas here – Paul/David as a police spy, Norma as a go-between – had been utilised, little difference would have been made to the fundamental situation.

By the Pricking of my Thumbs

11 November 1968

On a visit to Tommy’s Aunt Ada in Sunny Ridge Nursing Home, Tuppence meets Mrs Lancaster. Her subsequent disappearance intrigues Tuppence, who decides to investigate. This quest brings her to the village of Sutton Chancellor where the mystery is finally solved, but not before Tuppence’s own life is in danger.

By the pricking of my thumbs,

Something wicked this way comes.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

Tommy and Tuppence Beresford are the only Christie characters to age gradually between their first appearance and their last. In their first adventure, The Secret Adversary from 1922, they are ‘bright young things’, in 1941’s N or M? they are worried parents and by the time of By the Pricking of my Thumbs they are middle-aged. The chronology of their lives and ages does not bear close scrutiny, however, and gets even more complicated and, in fact, inexplicable, by the time of their final adventure Postern of Fate in 1973.

The notes for By the Pricking of my Thumbs are more unfocused than usual. They repeat the same scene with only minor variations, suggesting a lack of clarity as to where the book was going. And although the scenes in Sunny Ridge are intriguing, they are not enough to sustain an entire book. When Tuppence embarks on her investigation, the novel begins to flag and, unlike Christie’s plotting in her heyday, with a minimum of tweaking the final revelation could have been completely different with a totally different villain unmasked. Ironically, in Notebook 36 we find a note Christie wrote to herself: ‘Rewriting of first half – not so verbose – 1st three or four chapters good – but afterwards too slow’.

Notes are contained in two Notebooks, 28 and 36, and extend to just over 50 pages. We have, in Notebook 36, a clearly dated starting point for the writing of this novel just over a year before it appeared in the bookshops. The early pages of this Notebook encapsulate the opening of the plot. The first and second sections of the novel, ‘Sunny Ridge’ and ‘The House on the Canal’, are then sketched between Notebooks 28 and 36:

Behind the Fireplace – Oct. 1967

Tommy and Tuppence go to visit disagreeable Aunt Ada – she takes dislike to Tuppence who goes and sits in the lounge – old lady in there sipping milk – says it’s a very nice place – are you coming to stay here?

It wasn’t your poor child, was it?

No – I wondered – the same every day – behind the fireplace – at ten minutes past eleven exactly.

Then she goes out with her milk – Aunt Ada dies in her sleep four days later

Possible ideas for this

Is Mrs Nesbit the aunt or mother of a Philby or a Maclean [i.e. the British spies] – some well-known public character who defected to an enemy country. Were there papers? Hidden behind grate? Child knew secrets of Priest’s Hole. Aunt Ada dies – funeral – call at the home – does Tuppence see picture

Notebook 28 begins again with, broadly speaking, the same scene and set-up. And in it, we find the only Notebook reference to one of the most sinister and incomprehensible motifs in all of Christie – that of the child’s body behind the fireplace, a bizarre episode that also surfaces in The Pale Horse and Sleeping Murder. A possible explanation from within the plot of the novel, as distinct from within Christie’s own life, is offered by the extract above; but it is not very convincing. The idea is repeated but not developed, and the suggested reasons are not utilised in the finished novel.

Grandmother’s Steps

T and T – they visit nursing home for aged or slightly mental – Tommy’s Aunt Amelia – (scatty? Tommy Pommy Johnnie?) Tuppence left in sitting room – old lady sipping milk

‘Was it your poor child? It’s not quite time yet – always the same time – twenty past ten – it’s in there behind the grate, everyone knows but they don’t talk about it. It wouldn’t do’ Shakes her head.

‘I hope the milk is not poisoned today – sometimes it is – if so, I don’t drink it, of course’

Tuppence (on drive home) begins idly to think about it. ‘I wonder what she had in her head – whose poor child? I’d like to know Tommy’ [Chapters 2/3]

The House – kindly witch – the jackdaw – heard through wall? They go in – jackdaw flies away – a dead one – the doll. Tuppence makes enquiries – goes to churchyard – vicar – elderly – a bossy woman doing flowers in church. Vicar introduces her to Tuppence – she invites Tuppence in to coffee. Tuppence goes to house agent in Market Basing [Chapters 7/8/9]

A month later more plot developments, as well as possible characters, are considered. Some of these ideas – the painted boats and the superimposed name – were adopted, while it is possible that ‘The House by the Canal’ was under consideration as a title:

Nov 1st [1967]

The House by the Bridge or the Canal

Some points

The picture is of a small hump-backed bridge over a canal – across the bridge is a white horse on the canal bank – there is a line of pale green poplar trees – tied up to the bank, under the bridge are a couple of boats. An idea is that boats are an afterthought added some time after the picture was painted. Suppose a name was painted John Doe – murderer – over that the boats were painted. Someone either knew about this or someone did it

Ideas to pursue – or discard

1. Picture – boat superimposed – beneath it – ‘Murder’ [or] ‘Maud’

‘Come in to the garden, Maud’ a clue

‘The black bat, Night, hath flown’ – who painted it?

2. Baby farmer idea (at Sunny Ridge? Before Old Ladies Home?) Child really was dead and buried in chimney of sitting room there

3. Could cocoa woman be the killer woman

Possible people involved?

The artist Sidney Boscowan

The friendly witch Mrs Perry

Big lumbering husband Mr Perry

Vicar Rev. Edmund Shipton

Active woman Mrs Bligh

Tommy features little in the book until Chapter 10 when he starts to track Tuppence. One of his first tasks is to find out more about the painting in Aunt Ada’s room:

How does Tommy start his search?

Picture gallery – Bond St. – Boscowan – quite a demand for them again. Mrs. Boscowan lives in country. Tommy goes to see her – has Tuppence been there? Interested in her husband’s pictures. Tells her how this picture was given him by aunt now dead – she was given [it] by an old lady, a Mrs. Lancaster – no reaction. [Chapters 10 and 12]

Some of the ideas Christie noted in November 1967 were not pursued at all; others were partially adopted. The first one below was rejected possibly because of its similarity to a plot device in The Clocks, five years earlier; the second has elements that were utilised – the pregnant actress and the name Lancaster – but the surrounding ideas were discarded:

Does this really centre round a paperback – a thriller read by old Mrs Lancaster? Does Tommy find that out? He reads it in train, goes to Sunny Ridge, finds book was in library – Mrs L. very fond of crime stories – comes home triumphantly and debunks Tuppence

Country small lonely house – to it comes down beautiful girl – actress – going to have child. Man marries her – but he now wants to marry rich boss’s daughter so wedding is kept quiet (in local church) – under another name – he tells girl baby is dead? Or he kills girl. Who is Mrs Lancaster? Someone who lives near churchyard – sees body being buried in old grave

Five further sketches of the murderous back-plot appear; but as can be seen, each sketch is substantially the same, apart from a brief consideration of a homicidal Sir Philip Starke:

Nov. 12 [1967]

Alternatives

X Mrs Lancaster – alias Lady Peele – of batty family – barren – went queer. Husband loved children – she ‘sacrificed’ them. He gets his devoted secretary Nellie Blighe – sends her to nursing Old Ladies Home

Dec[ember]

Sir Philip Starke – loved children – his wife Eleanor – mental – (abortion) jealous of children – kills little girls. Nellie Bligh secretary – is also mental nurse.

Disappearance of child (Major Henley’s) – Does Nellie and Philip bury one of them in churchyard – Lady S – in various homes. Friendly witch’s husband was Sexton.

Was she Lady Peele – barren – had had abortion – was haunted by guilt – it was she, jealous, who killed any protégés of her husband. In asylum – released – then husband employs a faithful secretary to put her in old people’s home – ‘Miss Bates’ the one who was doing the church – she adores Peele

Candidates for murder

Lady Sparke – neurotic – mental. Did she kill her children? She was released – Philip and Nellie Bligh hid her – took her to homes. Does an elderly woman go in also – does she die? Mrs. Cocoa?

Story gets about that Sir Philip’s wife left him because he was the killer

Coming directly after the shocking and inventive Endless Night, By the Pricking of my Thumbs suffers, inevitably, by comparison. But although for the most part the book is a series of reminiscences with little solid fact, the opening chapters are certainly intriguing, conveying something of the old Christie magic, and the denouement is unsettling. The underlying themes of madness and child murder, combined with scenes set in graveyards and deserted houses, could well have justified, as suggested by the first-edition blurb which was written by Christie herself, the more appropriate title By the Chilling of your Spine.