Chapter 11

The Dark Lady . . .

‘Shakespeare is ruined for most people by having being made to learn it at school; you should see Shakespeare as it was written to be seen, played on the stage.’

Agatha Christie was a lifelong fan of William Shakespeare. Some of her titles – Sad Cypress, Taken at the Flood, By the Pricking of my Thumbs – come from his plays. Macbeth, with its Three Witches, provides some of the background to The Pale Horse; in Chapter 4 Mark Easterbrook and his friends discuss the play after attending a performance and in the village of Much Deeping, Thyrza, Sybil and Bella have a reputation locally as three ‘witches’. Iago, from Othello, is a psychologically important plot device in Curtain; a quotation from Macbeth – ‘Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him’ – follows the discovery of Simeon Lee’s body in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas; and Appointment with Death closes with a quotation from Cymbeline – ‘Fear no more the heat of the Sun.’ Her letters, written to Max Mallowan during the Second World War, include detailed discussions, instigated by nights at the theatre, about Othello and Hamlet.

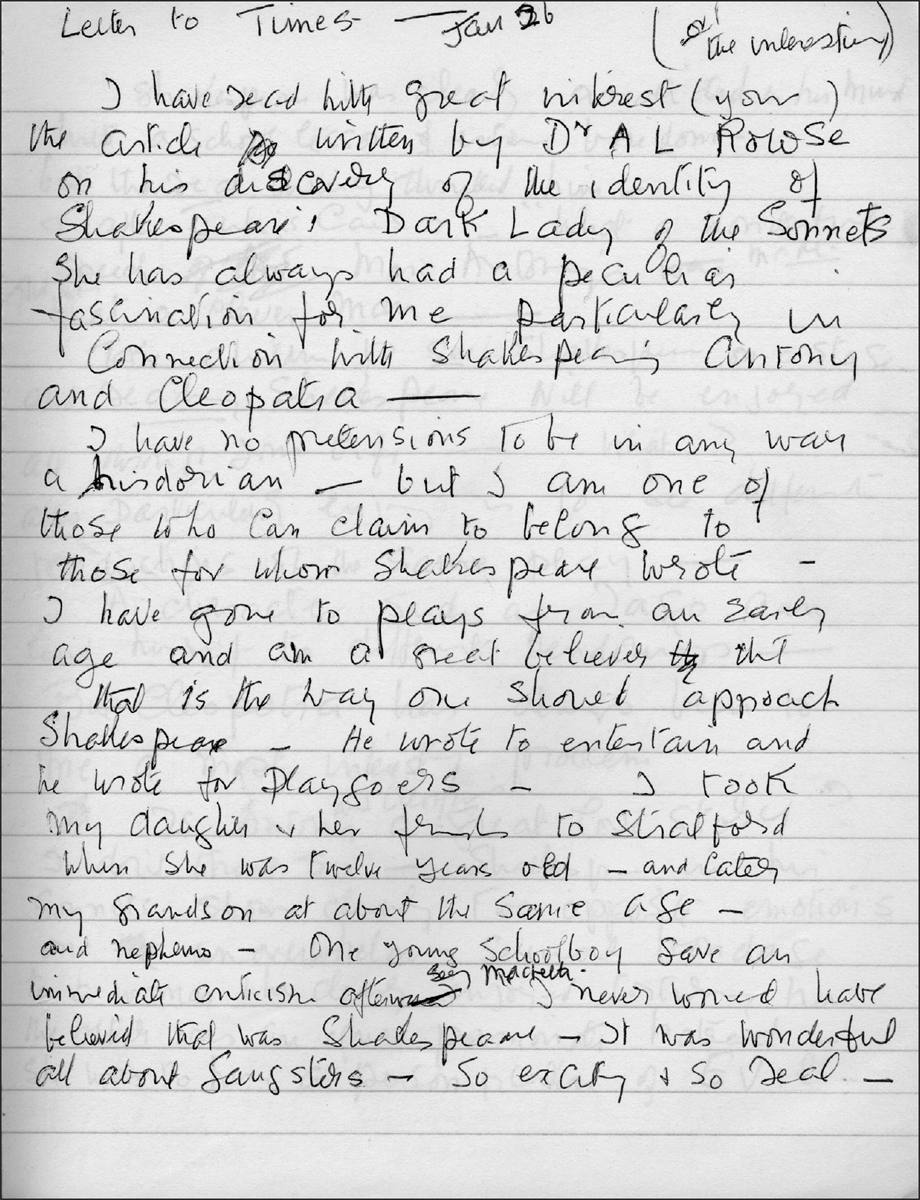

In The Times of 29 January 1973, the historian and Shakespeare scholar A.L. Rowse claimed that he had positively identified the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s Sonnets as Emilia Lanier née Bassano, daughter of a court musician and a former mistress of the Lord Chamberlain. Although disputed since, this theory received much publicity. In Notebook 7, in the middle of the notes for Postern of Fate, Christie drafted her response to this discovery:

A page of Christie’s handwritten draft of the ‘Dark Lady’ letter.

Letter to Times – Jan 26

I have read with great interest (your) the article written by Dr. A. L. Rowse on his discovery of the identity of Shakespeare’s Dark Lady of the Sonnets. She has always had a peculiar fascination for me particularly in connection with Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. I have no pretensions to be in any way a historian but I am one of those who can claim to belong to those for whom Shakespeare wrote. I have gone to plays from an early age and am a great believer that that is the way one should approach Shakespeare. He wrote to entertain and he wrote for playgoers – I took my daughter and her friends to Stratford when she was twelve years old and later my grandson – at about the same age – and nephews. One young schoolboy gave an immediate criticism afterwards seeing Macbeth – ‘I never would have believed that that was Shakespeare; it was wonderful, all about gangsters – so exciting, so real.’ Shakespeare was clearly associated in his mind with a school lesson of extreme boredom, but the real thing thrilled him. After Julius Caesar [he said] ‘What a wonderful speech Marc Antony made and what a clever man.’ Take children to see Shakespeare on a stage and reading Shakespeare will be enjoyed all through their life.

What I also particularly enjoy is to see different productions of the same play. A character such as Iago can lend himself to different renderings. But Cleopatra has always been to me a most interesting problem. Is Antony and Cleopatra a great love story? I don’t think so. Shakespeare in his sonnets shows clearly two opposite emotions; one an overwhelming sexual bondage to a woman who clearly enjoyed torturing him, the other was an equally passionate hatred. She was to him a personification of Evil. His description of her physical attributes, ‘hair cut like wire’, was all he could do to express his rancour, in those early times. But he did not forget. I think that, as writers do, he pondered and planned a play to be written some day – a study of an evil woman, a woman who would be a gorgeous courtesan and who would bring about the ruin of a man who loved her.

Is not that the real story of Antony and Cleopatra: Did Cleopatra kill herself with her serpent for love of Antony? Did she not, having tried to approach and capture Octavius so as to retain her power and her kingdom was she not tired of Antony? Anxious to become the mistress of the next powerful leader, Augustus not Antony, and he rebuffed her. And so, could it be that she would be taken in chains to Rome? That, never [and] so, charmian and the fatal asp. Oh, how I have longed to see a production of Antony and Cleopatra where a great actress shall play the Evil Destroyer and, Antony, the great warrior, the adoring lover is defeated

Dr. Rowse has shown in his article that Emilia Bassano (1597) was deserted by one of her lovers as an ‘incuba’, an evil spirit, and became the mistress of an elderly Lord Chamberlain, 1st Lord Hunsdon, who had control of the Burbage Players and so abandoned the gifted playwright for a rich and power-wielding admirer. Unlike Octavian he did not rebuff her. He was probably not a good actor, though one feels that that is really what he wanted to be. How odd it is that a first disappointment in his ambition forced him to a second choice, the writing of plays and so gave to England a great poet and a great genius. His Dark Lady the incuba, played her part in his career. Who but she taught him suffering and all the different aspects of jealousy, the green-eyed monster.

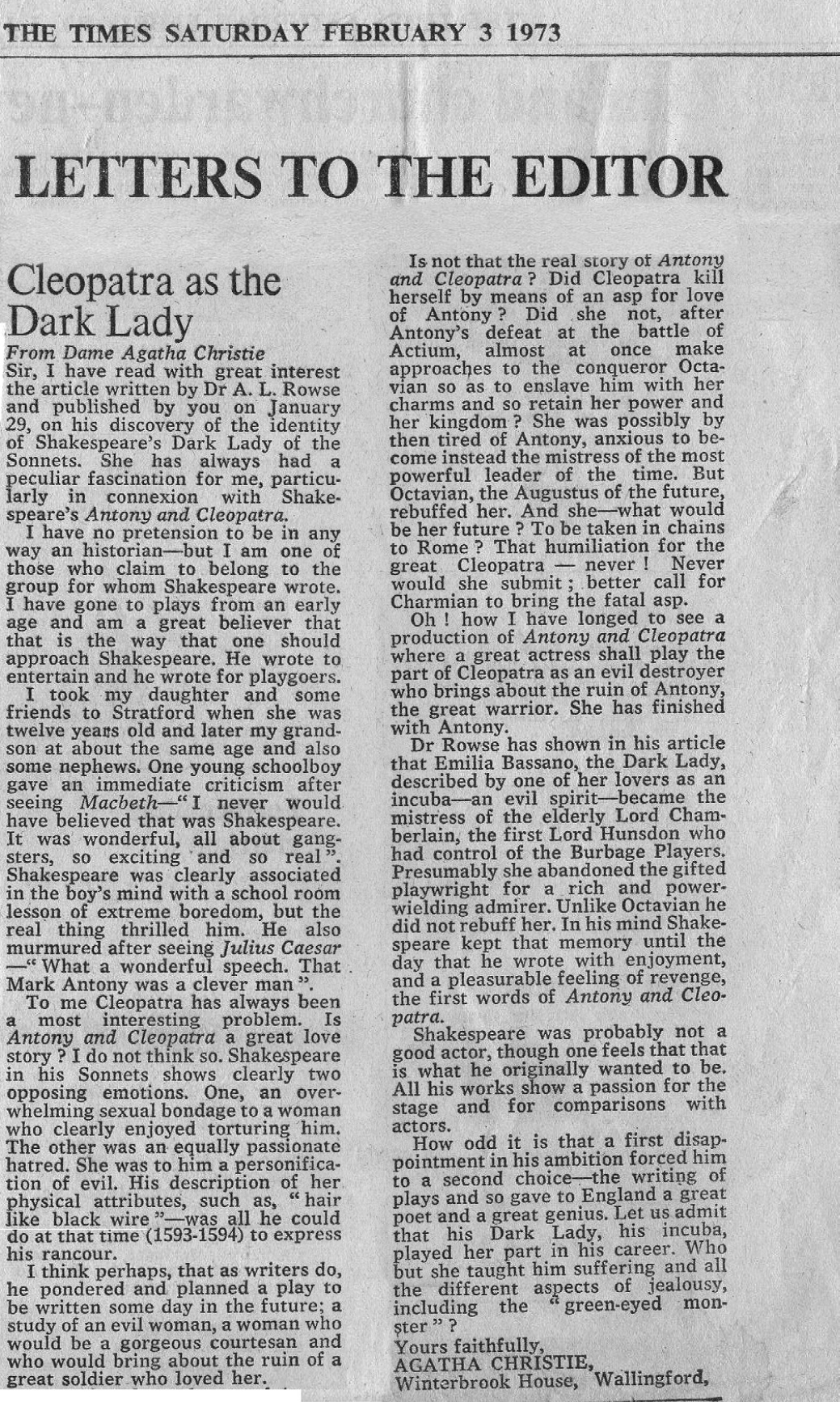

The edited version of Christie’s letter as it appeared in The Times on February 3rd 1973.

Although the Notebook is clearly dated ‘Jan. 26’, the article to which Christie refers was not published until three days later on 29 January. It is entirely possible that, because of her friendship with A.L. Rowse, she was aware of the forthcoming publication but it is more likely that she just wrote the wrong date. These notes were, presumably, tidied up when they were typed as the printed version is slightly different. The letter was published in The Times on 3 February 1973 as from ‘Agatha Mallowan, Winterbrook House, Wallingford’, with three further responses three days later. One took Dame Agatha to task for accepting ‘interesting conjectures as irrefutable proof’ and reminding her that Hercule Poirot would not have made the same mistake. Another challenges her portrayal of Cleopatra as a ‘cheap femme fatale’.

In his book Memories of Men and Women (1980), Rowse has an affectionate chapter on his friendship with Agatha and Max, a friendship which began through Max’s election as a Research Fellow in All Souls, Oxford, Rowse’s own college. Recalling that she wrote him a ‘warm and encouraging letter’ about his Shakespeare discoveries as being ‘from the mistress of low-brow detection to the master of high-brow detection’, he mentions her support with this letter to The Times and her subsequent attendance at his lecture on the subject at the Royal Society of Literature.