Chapter 12

The Sixth Decade 1970–1976

‘Thank God for my good life, and all the love that has been given to me.’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

Nemesis

In 1970 Agatha Christie celebrated her eightieth birthday; with the employment of a little selective arithmetic, it was also the year of her eightieth book. Extensive press coverage, both at home and abroad, greeted the publication on her birthday – 15 September – of Passenger to Frankfurt.

On the first day of the following year Agatha Christie became Dame Agatha, to the delight of her global audience. As she worked in Notebook 28 on that year’s book, Nemesis, she wrote ‘D.B.E.’ (Dame Commander of the British Empire) at the top of the page. A book more impressive in its emotional power than in its plotting, Nemesis is, like its 1972 successor Elephants Can Remember, a journey into the past where ‘old sins cast long shadows’. And the last novel she wrote, Postern of Fate (1973), is a similar nostalgic journey and the poorest book of her career (with the possible exception of the curiosity that is Passenger to Frankfurt); one which, in retrospect, should never have been published. To counterbalance these disappointments, 1974 saw the publication of Poirot’s Early Cases, a collection of short stories from the prime of the little Belgian and his creator, not previously published in the UK. (See Chapter 3, ‘Agatha Christie’s Favourites’.)

Coinciding with these reminders of the vintage Poirot, one of his most challenging cases, Murder on the Orient Express, was filmed faithfully and extravagantly by Sidney Lumet, working with an all-star cast. A massive critical and popular success worldwide, it became the most successful British film ever and created a huge upsurge of interest in the now frail Agatha Christie. Her last public appearance was at the Royal Premiere in London, where she insisted on remaining standing to meet the Queen. Her publishers knew that a new book would be unable to satisfy the appetite of the vastly increased Christie audience created by the success of the film. So Sir William Collins convinced Dame Agatha to release Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, one of her most ingenious constructions, written when she was at the height of her powers. Another global success followed its appearance in October 1975, heralded by a New York Times front-page obituary of Hercule Poirot.

On 12 January 1976, three months after her immortal creation, Dame Agatha Christie died at her Wallingford home. International media mourned the passing of, quite simply, ‘the writer who has given more enjoyment to more people than anyone else’ (Daily Telegraph); the perennial Mousetrap dimmed its lights and newspapers printed pages on ‘the woman the world hardly knows’. She was buried at Cholsey, near her Oxfordshire home, and a memorial service was held in May at St Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Sleeping Murder, another novel from Christie’s Golden Age, and the ‘final novel in a series that has delighted the world’ (to quote the blurb) was published in October and presented Miss Marple’s last book-length investigation. Dame Agatha’s Autobiography followed in 1977 and Miss Marple’s Final Cases, a collection of previously uncollected short stories, in 1979.

Apart from the unparalleled success of Murder on the Orient Express, the much-underrated screen version of Endless Night had appeared in 1972. Despite Dame Agatha’s objection to a love scene at the close of the film, this adaptation remains a faithful treatment of the last great novel that Christie wrote. The previous year the last Christie play, Fiddlers Five (reduced to Fiddlers Three in a subsequent version in 1972), was staged, but its lack of critical and popular success ruled out a West End production. In 1973 Collins published Akhnaton, her historical play, written in 1937 but never performed; and her poetry collection, called simply Poems, was also issued in 1973.

The final six years of Agatha Christie’s life saw some of her greatest successes – her damehood, the universal successes, in two separate spheres, of Murder on the Orient Express and Curtain – but also the publication of some of her weakest titles. But by then it didn’t matter. Such was the esteem and affection in which she was held by her worldwide audience that anything written by Agatha Christie was avidly bought by a multitude of her fans, many of whom had had a lifelong relationship with her.

Passenger to Frankfurt

15 September 1970

Diverted by fog to Frankfurt Airport, Sir Stafford Nye agrees to the fantastic suggestion of a fellow passenger. On his return to England he realises that he has become involved in something of international importance – but what? A further assignation leaves him little wiser. What is Benvo? And who is Siegfried?

Published on her eightieth birthday, this was claimed to be Agatha Christie’s eightieth book and, despite the dismay with which the manuscript was greeted by both her family and her publishers, it went straight into the best-seller lists and remained there for over six months. The publicity attendant on the ‘coincidence’ of her birthday and her latest production certainly helped, but Passenger to Frankfurt remains the most extraordinary book she ever wrote. Described, wisely, on the title page as ‘An Extravaganza’ – the description went some way towards mitigating the disappointment felt by both publishers and devotees – and showing little evidence of the ingenuity with which her name is still associated, this tale of international terrorism and engineered anarchy is difficult to write about honestly. Most fans, myself included, consider it an aberration and, but for the fact that it is an ‘Agatha Christie’, would never have read it the first time, let alone re-read it over the 40 years since its first appearance. Like other weaker novels from the same era, it begins with a compelling, if somewhat implausible, situation, but it degenerates into total unbelievability long before the end. Only in the closing pages of Chapter 23, with the unmasking of a completely unexpected, albeit incredible, villainess is there a very faint trace of the Christie magic.

The idea of stage-managed anarchy brought about by promoting student protest and civil unrest is not new in the Christie output. It reaches back as far as the mysterious Mr Brown in The Secret Adversary and also makes an appearance, 30 years later, in They Came to Baghdad. While both these examples demand some suspension of disbelief on the part of the reader, Passenger to Frankfurt demands a higher and longer suspension. The other echo from earlier works, and one that can be appreciated only now, after the publication of the alternate version of ‘The Capture of Cerberus’ (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks), is the subterfuge about a fake/real Hitler character and the method of concealment. This element of the plot is identical in both the short story and the novel, written 30 years apart.

The other surprise about this novel, apart from the unlikeliness of the plot, is the fact that throughout her life Christie evinced little interest in politics. And yet the entire thrust of the novel is political, with politicians and diplomats meeting regularly and, it must be said, implausibly in attempts to maintain political stability. Such scenes are dotted throughout the book; although, despite these meetings and endless conversations, nothing happens. Most of the conversations, whether private or political, meander aimlessly and unconvincingly and swathes of the book could be removed without making any notable difference.

The character of Matilda Cleckheaton is, in many ways, a Marple doppelganger – elderly, observant, worldly-wise and devious. But her stratagem for dealing with ‘Big Charlotte’ is in the highest degree unlikely and unconvincing.

Passenger to Frankfurt was written in the year of publication and Notebook 24 has three dates, ‘1970’, ‘February 1970’ and ‘16th February 1970’, on pages 12, 14 and 17 respectively. Christie realised that the year of her eightieth birthday would inevitably involve publicity and that the 1970 ‘Christie for Christmas’ would have to be finished earlier than usual for a September publication. Some selective arithmetic had to be done to arrive at the significant figure of 80 titles. Only by counting the American collections – The Regatta Mystery (1939), Three Blind Mice (1950), The Underdog (1951) and Double Sin (1961) – all of which contained stories not then published in Britain, as well as the Mary Westmacott titles, could this all-important figure be arrived at.

In an interview conducted shortly after the publication of the book Christie denied that any of the characters were based on real-life politicians and that her inspiration for writing the book was her reading of the daily newspapers. She cited especially reports of rebellious youth and the fact that youth can be more easily influenced than older people. She was at pains to emphasise that, personally, she was ‘not in the least interested in politics’ and that the novel was apolitical in the sense that anarchy could originate from either the Right or the Left. Much of this is echoed in the Introduction to the novel where she also discusses her ideas and where and how she got them. ‘If one idea in particular seems attractive, and you feel you could do something with it, then you toss it around, play tricks with it, work it up, tone it down, and gradually get it into shape.’ It is a sad irony that, of all her novels, Passenger to Frankfurt is one where the ingenious ideas that proliferated in other novels are notable only by their absence.

The opening gambit of the airport swap is one that, nowadays, would be practically impossible; in the less terrorist-conscious days of the late 1960s, when the book was plotted, it was just about feasible. But this feasibility does not extend to believability: is it remotely likely that anyone would agree to hand over their passport to a total stranger and then take a drink with the assurance of that stranger that the drug that it admittedly contained was harmless? This ploy is considered in six Notebooks with the earliest, in the first extract below, dating back to around 1963. As usual, details of names and airport locations were to change, but the basic situation remains the same:

Possibilities of Airport story (A)

After opening in central European airport (Frankfurt) (Venice) – diversion of plane – substitution of girl for Sir D

Starts at European airport – woman, tall, sees a medium man wearing a distinctive cloak and hood. Asks him to help her – Sir Robert Old – she takes his place – he takes knock-out drops. Later woman contacts him in London. Thriller

D. Book

Starting at airport – substituting – Robin West – international thinker type

B. Missing passenger

B. Passenger to Frankfort [sic]

Missing passenger – airport – Renata – Sir Neil Sanderson

B. Passenger to Frankfurt

Sir Rufus Hammersley – his cloak – med[ium] height – sharp jutting feminine chin.

In Notebook 23 the first sketch above – ‘Possibilities of Airport story’ – continues at ‘A.’ below. But the scenario considered after the postcard and ‘near escape’ idea goes in a completely different direction from the one adopted in the novel. The ‘Girl murdered’ idea is rather similar to that of Luke Fitzwilliam’s reading of the death of Miss Pinkerton following their meeting on the train in Murder is Easy. These notes appear on a page directly preceding the plotting of 1964’s A Caribbean Mystery and this timeline is confirmed by the date of the proposed postcard, November 1963.

A. Advertisement?

Postcard? Frankfort 7-11-63 Could meet you at Waterloo Bridge Friday 14th 6 p.m.

B. Sir D. is called upon by a rather sinister gentleman – questioned about incident at Frankfort – D. is alert – non-committal. Shortly after, a ‘near escape’ – gas? car steering trouble? electric fault? Then a visit from the ‘other side’ apparently friends of girl

Or

Girl murdered – her picture in paper – he is sure it is the girl at the airport – it starts him investigating – he goes to the inquest.

Notebook 28A contains the plot-line that Christie actually adopted and the following short paragraph, listed as Idea B, neatly encapsulates it. Although the calculation about the age of the supposed son would seem to place the writing of this note in 1969, Idea C on the following page is part of the plot of Endless Night (1967) and is followed a few pages later by extensive notes for By the Pricking of my Thumbs (1968). Unusually, here also is the exact title, spelling apart, of the projected book:

Passenger to Frankfort [sic]

Missing passenger – airport – Renata – Sir Neil Sanderson

London Neil at War Office or M.14. His obstinacy aroused – puts advertisement in. Frankfort Airport Nov. 20th Please communicate – passenger to London etc. Answer – Hungerford Bridge 7.30pm

What is it all about? She passes him ticket for concert Festival Hall. Hitler idea – concealed in a lunatic asylum – one of many who think they are Napoleon or Hitler or Mussolini. One of them was smuggled out – H. took his place – Hitler – H. Bormann – branded him on sole of foot – a swastika – the son born 1945 now 24 – in Argentine? U.S.A.? Rudi Schornhorn – the young Siegfried

The following extract from Notebook 49 dates from the mid 1960s. Idea A on the same list became Third Girl and Ideas C and D never went further than the four-line sketches on the page of this Notebook. This outline tallies closely with the finished novel although there is no mention of the ticket and passport swap.

B. Passenger to Frankfurt

Sir Rufus Hammersley – His cloak – med[ium] height – sharp jutting feminine chin. Fog in airport – flight diverted – the young woman – not noticeable – thinks he has seen her before – likeness – she will be killed – because of the fog – diverted elsewhere – Miss Karminsky – passenger – he is found in passage by loos – no money or papers

He gets money sent him – then asked to go to Intelligence. He has a sixth sense and a feeling of partisanship. His things searched. Advertisement – wants to see you again – Hungerford Bridge – Nov. 26th Ticket at concert. What is it all about

Probably because this novel did not involve clues and suspects and alibis, the usual components of a Christie detective novel, there is little in the way of notes or ideas that were considered and discarded. In fact, it is fair to say that there is little in the way of plot at all in Passenger to Frankfurt. Apart from speculation about rearranging some sections, the notes for the novel are mostly of the names of people and their countries and the interminable meetings that fill the book. The following early notes show uncertainty about the arrangement of some passages in the opening chapters. The seemingly odd reference ‘Lifeboat’ is to the name of the periodical used to conceal the safe return of Sir Stafford’s passport.

Chapter 3

Car incident p. 51 – or keep it as original – or keep it on p. 46

Last page rearranged – Start at breakfast – Interview at ministry. After ministry interview into Mrs. Worrit – clothes cleaned – man – panda?

Rings Matilda – arranges to go down next week. Dinner with Eric – on way home car business – Lifeboat – passport – advertisement idea

A passage of considerable interest is the one concerning the antecedents of Siegfried, ‘the young hero, the golden superman’ of Chapter 6. Chapter 17 of Passenger to Frankfurt contains distinct echoes of the ‘new’ version of ‘The Capture of Cerberus’, published in Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks. Remarkably, after a 30-year gap, the central idea of the short story is recycled in the novel – the asylum with its many incarnations of famous, and infamous, people. In each case there is confusion about the ‘fake’ and the ‘real’ Hitler (Hertzlein in the short story) and the eventual release of the ‘real’ one. A major difference in the short story is that the newly released character has become a force for good and not evil, as in the novel.

Are you suggesting he is Hitler?

No, but he believes he is.

Statistics – Borman hid him there – he married a girl – child was born – swastika branded on

child’s foot – Renata has birth certificate [Chapter 17]

Some characters from earlier titles reappear. Mr Robinson, first mentioned in Chapter 3, and Colonel Pikeaway in Chapter 4, both appeared in both Cat among the Pigeons and Colonel Pikeaway also appeared in At Bertram’s Hotel; these two shadowy figures would make a further reappearance in Postern of Fate. Matilda Cleckheaton’s nurse, Amy Leatheran, on the other hand, is unlikely to be the same Amy Leatheran who narrated Murder in Mesopotamia; she is described in Chapter 20 of Passenger to Frankfurt as a ‘tactful young woman’. Other interesting passages include a discussion, in Chapter 6, of The Prisoner of Zenda, to be discussed again by Tommy and Tuppence in Postern of Fate; an inadvertent naming of two Christie plays in a paragraph of Chapter 11; and a distinct reference, in Chapter 22, to the basis of the 1948 radio play Butter in a Lordly Dish. More personally, Lady Matilda’s discussion of medicines in Chapter 15 is an echo of Christie’s own description, in her Autobiography, of her work in the dispensary in Torquay.

Overall, the decline that began with Third Girl reached its nadir with Passenger to Frankfurt; the superb Endless Night beams out like a shining light among the last half-dozen novels. But there can be little doubt that the only reason that Passenger to Frankfurt was even published was that it had the magic name ‘Agatha Christie’ on the title page.

Nemesis

18 October 1971

At the posthumous request of Mr Rafiel, from A Caribbean Mystery, Miss Marple joins a coach tour of ‘Famous Houses and Gardens’. She must use her natural flair for justice to right a wrong. But she is mystified by a lack of clues – until one of her fellow travellers is murdered.

Like its predecessors, By the Pricking of my Thumbs and Hallowe’en Party, and its successors, Elephants Can Remember and Postern of Fate, Nemesis is concerned with a mystery from the past. Retrospective justice is what Miss Marple is asked, by the deceased Mr Rafiel, to provide. And, similar to the letter received by Poirot at the outset of Dumb Witness, the posthumous correspondence from Mr Rafiel is very short on detail.

In one way Nemesis is the most surprising novel that Christie wrote in her declining years. As with most of the novels from her last decade Nemesis is rambling and repetitive, and it is disappointing as a detective novel. The coach tour, which promises much as a traditional Christie setting, is almost a red herring. And unlike the classic settings of Murder on the Orient Express, Death in the Clouds and Death on the Nile, where a mode of transport isolates a group of suspects, the vital characters in Nemesis, the three sisters, are all to be found outside the coach.

Yet, though it is not a great detective novel – clues to its solution are remarkable only by their absence – considered solely as a novel it is a revelation. Its theme is ‘Love – one of the most frightening words there is in the world’, according to Elizabeth Temple at the close of Chapter 6. The mainspring of the plot is the smothering, corrosive love of Clotilde Bradbury-Scott for the girl Verity. As a counterbalance to this claustrophobic situation there is the love of Verity for Michael Rafiel; but this love is also destined for tragedy. The doomed worship of Verity by Clotilde is the root cause of three deaths – the object of that love and the brutal killing of two innocent onlookers. This hitherto unexplored theme has powerful emotional impact, especially in the closing explanation which, unusually for Miss Marple, takes over 15 pages.

Like the novel itself, the notes for Nemesis are not very detailed. The bulk of them concern the crime in the past and its possible variations. The idea of the three sisters and the tomb disguised as a greenhouse seems to have been settled in the early stages of planning. This has distinct echoes of a similar plot device in Hallowe’en Party, where a sunken garden fills a similar role; and, earlier again, Dead Man’s Folly, which features a folly as a grave. The notes for Nemesis are in four Notebooks and, as can be seen from the first extract below, work on it began just a year before publication. Note the incorrect name ‘Raferty’ instead of Rafiel:

Oct. 1970

Chapter I

Miss Marple at home reading Times – glances at Marriages – then Deaths. A name she knows – can’t quite remember. Later in garden remembers Carribean [sic] – Raferty, the dying millionaire.

Chapter II Letter from lawyer in London.

The Three Sisters – invitations to Miss Marple – Mr. Rafiel – old manor house – a body concealed there

Clothilde

Lavender

Alicia

What kind of a house? What garden

A Greenhouse – wreathed over with polygnum – fell down or collapsed in war

This list of characters from Notebook 6 reflects, with the exception of the Denbys and Miss Moneypenny, that of the completed novel.

People on Tour

Mrs. Risely-Porter (Aunt Ann) Elderly dictatorial a snob

And niece Joanna Cartwright (27)

Emlyn Price (Welsh and revolutionary)

Miss Barrow and Miss Cooke (spinster friends)

Miss Moneypenny (Cats) [possibly Miss Bentham or Lumley]

Mr and Mrs. Butler Americans middle-aged

Colonel and Mrs. Walker (Flowers? Horticulture)

Mr Caspar (Foreign) about 50

Elizabeth Peters [Temple] Retired headmistress

Schoolgirl and brother – Liz and Robert Denby

Professor Wanstead

A section of Notebook concerning the murder of Elizabeth Temple appears almost word for word in Chapter 11, ‘Accident’. Details differ – the school is Fallowfield, not Grove House Park, and it is Joanna Crawford and not Mr Caspar who provides most of the details of the rock fall – but in essence this extract is an accurate précis:

Death of Elizabeth Peters, late headmistress of Grove House Park Girls’ School – or is she in hospital? Does Miss M go and see her?

Does Emlyn Price come and tell Miss Marple of accident? She goes to local hotel to see other travellers – group talk and chat. Either Miss Cooke or Robert Denby describe what they saw – 4 or 5 boys climbing up – throwing stones – pushing a rock – local boys. Mr Caspar later says that was not what happened – it was a woman. Tells Miss Marple – he was a botanist and had wandered by himself. Professor Wanstead speaks to Miss Marple – mentions Mr. Rafiel – suggests Miss Marple should go and visit her. He stresses Rafiel told him about her

It must be said however that as a murder method, rolling a rock down a hillside in the hope of hitting a moving target is, at best, imprecise; 35 years earlier, on the banks of the Nile, Andrew Pennington discovered this when his murder attempt on Linnet Doyle failed, literally, to achieve its target. And for a middle-aged murderess it is also very unlikely and impractical.

The essence of the plot appears in Notebook 28 and, apart from a few details – Gwenda and Philip are forerunners of Verity and Michael – is reproduced in the book. It would seem to have been written early in the plotting as it appears directly ahead of a page dated ‘Jan. ’71’; and it is written straight off with no deletions or changes. The ruse of the ‘pinched’ car and the obliterated body has familiar echoes from The Body in the Library, 30 years earlier.

Elizabeth Peters 60 retired headmistress

A girl in her school – one of the 3 sisters had taken her up, trip abroad art galleries. Girl had finally come to live with her – girl was murdered by 19 or 20 years old young man – picked her up in car (evidence that he did). Body found 20 miles away – face disfigured – identified by Miss C – says a mole by elbow or above knee – a small silver cross or some other trinket – pregnant – 6 weeks only. A scarf (Persian? or Italian?) Red hair – auburn or black hair – Girl used to take local bus to nearby Town – meet Philip there – C[lothilde] finds out Gwenda and Philip – baby coming – going to marry. Strangles her – hides body in garden – plans another girl whom she knows – drugs her – drives her in car she has pinched 20 miles away in quarry – obliterates features – moles – jealous

Midway through Notebook 28 we find a touching note. In the New Year Honours list for 1971 Agatha Christie became Dame Agatha, a fact that she noted as she resumed work on Nemesis. On a more practical note, this means that she was less than halfway through the novel at the beginning of the year, with the submission date three months away. And she was 80 years of age.

D.B.E. [Dame of the British Empire]

Nemesis – Jan 1971

Recap – death of Mr. Rafiel in Times – Miss Marple

Point reached – Elizabeth Peters retired headmistress – accident as climbing – stones and rocks rolling down hillside – concussion – hospital

Professor Wansted and Miss Marple

As she tidied the manuscript, to judge by the date, Christie listed the characters again, this time with a few additions. The final proofs were corrected by Dame Agatha while she recovered from a broken hip in June/July 1971, at which stage she also wrote the jacket blurb.

Notes on ‘Nemesis’ March 18th ’71

Elizabeth Temple School Fallowfield

Justin (?) Rafiel

Michael Rafiel – Verity Hunt

Miss Barrow – Miss Cooke – or Miss Caspar

The Old Manor – Jocelyn St. Mary

Clothilde Bradbury Scott – Lavinia – Anthea

Archdeacon Bradshaw Bradley Scott?

Emlyn Price

Joanna Crawford Mrs Riseley-Porter

Professor Wanstead

Broadribb and Schuster (Solicitors)

She also gives a proposed list of chapters, with some notes to herself:

Chapter I Births Marriages and Deaths

Chapter II Letter from Mr. Rafiel

Chapter III Note – a little cutting of this chapter?

Chapter IV Esther Waters

Chapter V Instructions from beyond – some cuts?

Chapter VI Elizabeth Temple

Chapter VII An Invitation

Chapter VIII The Three Sisters

This list is not exactly reflected in the novel, but the suggested title of the opening chapter here is surely better than that eventually decided upon. ‘Overture’ is not thematically inked with any other chapter, while ‘Births Marriages and Deaths’ is both accurate and intriguing.

Elephants Can Remember

6 November 1972

At a literary dinner, Mrs Oliver is asked to investigate the double death years earlier of Sir Alistair and Lady Ravenscroft. Did he kill her and then himself or was it the other way round? Hercule Poirot journeys into the past to arrive at the truth.

The adage ‘Old sins have long shadows’ runs like a motif through Elephants Can Remember, the last Poirot novel that Agatha Christie wrote. At its heart is a plot involving typical Christie ploys – mistaken identity, impersonation and misconstrued deaths – culminating in a last chapter reminiscent of the closing scene in Five Little Pigs with a group of people gathering at the scene of an earlier tragedy in order to learn the poignant truth. If it had been written 20 years earlier there can be little doubt that the plot would have been developed in a more ingenious fashion. As it is, the book is a series of conversations, with little action; and like its successor, Postern of Fate, the chronology of the earlier crimes will not bear close examination, a fault for which the elderly Christie’s editors must accept some responsibility.

Old friends make reappearances: Mrs Oliver plays a large part and Superintendent Spence reminisces in Chapter 5 about Mrs McGinty’s Dead, Hallowe’en Party and Five Little Pigs, all stories where Poirot investigates past crimes, the first two also in the company of Mrs Oliver. In Chapter 10 Miss Lemon, Poirot’s secretary, appears briefly. Mr Goby, described in Chapter 16 as ‘a purveyor of information’, first appeared in The Mystery of the Blue Train, and also conducted enquiries on behalf of Poirot in After the Funeral and Third Girl.

There can be little doubt that it is Agatha Christie herself rather than Ariadne Oliver who muses throughout the first chapter on the difficulties of eating with false teeth, the horror of giving speeches, the difficulties of dinner-party companions and the unwarranted effusiveness of fans. And the passage in the same chapter in which Albertina remonstrates with Mrs Oliver about her diffidence is echoed in Christie’s Autobiography when she describes how the wife of the British ambassador to Vienna had encouraged her to abandon her natural shyness and declare to reporters, ‘It is wonderful what I have done. I am the best detective story writer in the world. Yes, I am proud of the fact . . . I am very clever indeed.’

There are fewer than 20 pages of notes, scattered over four Notebooks, for Elephants Can Remember. Notebook 5 contains six pages of notes but only the first few lines are relevant to the finished novel. In strong legible writing at the top of the first page of Notebook 5 we read:

Elephants Remember – Jan. 1972

Despite its incongruity in a crime novel it would seem that the title, or a slight variant of it, was settled from the beginning. The elephant motif recurs throughout the book – often in defiance of logic, for example the reference in the first chapter to Mrs Burton-Cox’s teeth.

In the following extract Mrs Gorringe is the forerunner of Mrs Burton-Cox and, although their discussion about hereditary violence is not used, the last idea, a godchild and her fiancé, is. Details from this extract – Mrs Oliver’s birthday and the ‘bull in the field’ memory – tally exactly with Chapter 1.

Mrs. Oliver – Poirot

Does a problem come to P? or Mrs. O? Lunch for literary women – Mrs. Oliver – Mrs. Gorringe

Mrs G. ‘Do you think that if a child had grown up she might have been a murderer- murderess?’

Boys pull fly’s legs off but they don’t do it when they grow up – just boyish fun. Are you very interested in these things?

Not really – it’s just because of one particular thing – a god child I’ve got – she’s got a boyfriend – she wants to marry him. (Interruption – Speeches) They go and sit and look at the Serpentine.

All so long ago – everyone would have forgotten. People don’t forget things that happen when they were children – Mrs. O remembers cows a bull in a field – a birthday and something to do with an éclair. It’s like elephants – elephants never forget

After a brief detour to consider an alternative and to remind herself to re-read an early Poirot short story with a very similar plot, Christie outlines the opening of Elephants Can Remember in Notebook 6, almost exactly as it appears in the published novel:

Idea A

Husband and wife – she says her husband is poisoning her – (wants to believe it) attracted to a young man who pretends he is in love with her – actually is also courting niece tells wife he is pretending this to deceive husband. Really, he and niece are in on it. Re-read ‘Cornish Mystery.’

Idea B

Mrs. O goes to literary lunch – bossy female buttonholes her. I believe Celia Ravenscroft is your god-daughter? My son wants to marry her. Can you tell me if her mother killed her father or was it [her] father killed [her] mother. Celebrated case – you must remember – both bodies on cliff – both shot.

Mrs. O goes to Poirot or does she get Celia to come and see her. Modern – violent – intellectual girl – says definitely of course mother shot him – gives reason – story of what lay behind it. Mrs. O gets interested. Talks to Poirot

A few pages later we find a mixture of ideas, some of which found their way into the finished book. These notes are somewhat confused and confusing – references to the wife/sister are not always clear – but the underlying plot of two sisters, one husband and lifelong jealousy ending in murder and impersonation eventually emerged. There is an echo of the Christie of old in the listing of alternatives, although most of them are variations on a theme.

Further ideas

Is it actually Col. R has shot himself – wife is not his wife – a sister in law – elder sister of wife – has been in nursing home or mental Home for killing children – unfit to plead

Or Col. R’s sister or his first wife – a tragedy in India – she is paroled from mental home. Dressed in wife’s clothes and wig. Wife pretends to be sister – identifies body.

Sisters one is mental – kills children – unfit to plead – in Broadmoor

or

Colonel’s sister – devoted to him – jealous of his wife. Paroled – comes to house – kills brother – wife shoots her – dresses her in wig and clothes – stages it all – identifies wife’s body –

or

India Col. has wife/sister? – mental kills child – Ayah accused – poisons herself. But was it the ayah? Could it have been sister in law or the mother? [Chapter 7]

Story about Mrs. Ravenscroft sister in India – nervous breakdown – killed a child – hushed up taken back to England – nursing home.

Story – Wife and mother killed child

Story – Sister of Col – or Mrs. R – said to be accident. Goes now to England in private mental home – released – lives with a qualified mental nurse – nurse dies – sister in law marries.

There is a reference to one of the ideas Christie regularly toyed with, that of the twins (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks); this motif does come into play in the novel, although not exactly as Christie here speculated. And the second reference below, from Notebook 6, is a plot very similar to the Marple short story ‘The Case of the Perfect Maid’; apart from the idea of twins, it has little to do with Elephants Can Remember.

Twin idea – 2 girls born same day – one girl tells her they are identical – nobody knows them apart

Lalage and Lorna identical twins – born same day but really not identical – look quite different – come from Australia or New Zealand. Lalage plays part of both sisters – 3rd person in house is Stephanie (really Lorna). Play part of maid or one time au pair girl – foreign accent etc. actually looks like her Aunt (mother’s sister Francesca)

One of the ideas noted by Christie, however, appears in Chapter 6 as a red herring:

Colonel R – is doing reminiscences of his days in India – girl secretary comes – takes dictation from him and does typing. Suggestion that there was something between them

Despite showing a glimpse in the final chapter of the Christie of yesteryear, Elephants Can Remember remains a disappointment. Like the books published on either side of it, there are too many rambling conversations that give the reader little solid information but merely repeat what we have already been told. The central idea has possibilities and there is certainly material for a long short story. It could have been a disappointing swan song for Poirot – but the Queen of Crime had reserved a dazzling final performance, Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, for the little Belgian.

Postern of Fate

29 October 1973

While shelving books in her new home Tuppence Beresford finds a hidden message concerning the mysterious death of a previous inhabitant. With the help of Tommy she investigates a mystery from the distant past, unaware that new danger is very much in the present.

Postern of Fate was the last book Agatha Christie wrote and the initial notes are clearly dated November 1972, almost exactly a year before publication. It is arguable that her agent and publisher should never have asked for another book after the previous year’s Elephants Can Remember. Although H.R.F. Keating reviewed Postern of Fate charitably in The Times with the ambiguous phrase ‘She stills skims like a bird’, there is no doubt that it is the weakest book Christie ever wrote. The most interesting passages are those where we get a glimpse of the private Agatha Christie. Old Isaac’s reminiscences in Book II, Chapter 2 (‘Introduction to Mathilde, Truelove and KK’) echo Christie’s own memories of her childhood as described in Part I of her Autobiography. Many of the books mentioned by Tommy and Tuppence in the early chapters of the book – The Cuckoo Clock, Four Winds Farm, The Prisoner of Zenda, Under the Red Robe – are still to be found on the shelves of Greenway House, her Devon home. The description of The Laurels bears more than a passing resemblance to Ashfield, her beloved childhood home, even down to the monkey puzzle tree in the garden; and the first UK edition has on the jacket a photo of Bingo, Christie’s own family dog and the inspiration for the novel’s Hannibal. And when Tuppence complains about the effects of old age or the vagaries of workmen (‘They came, they showed efficiency, they made optimistic remarks, they went away to fetch something. They never came back’), we can be certain that this is the elderly Christie speaking.

Interesting though these insights are – and they were to be superseded within a few years by publication of her Autobiography – they do not make a detective novel and there can be no argument that Postern of Fate is even a pale imitation of the form at which, for half a century, she excelled. The novel’s intriguing opening premise, the coded message in the book, clearly shows that advancing age did not prevent Christie having ideas; what was missing was the ability to develop them as she would have even a decade earlier. All of the final half-dozen novels, from By the Pricking of my Thumbs onwards, begin with a fascinating idea – the disappearance of an elderly lady from her retirement home, the drowning of a child while bobbing for apples, the supposed double suicide of an elderly couple – but none of them is explored with anything approaching the ingenuity of Christie’s yesteryear. As recently as two years earlier, Nemesis begins with a situation very similar to that of Postern of Fate – a message from the dead that demands an investigation. But the decline in those two years is all too evident and dramatic; the plot of Nemesis is coherent and reasonable and the action of the story moves forward throughout. All of these elements, sadly, are absent from Postern of Fate.

Not surprisingly this decline is mirrored in the two Notebooks, 3 and 7, which contain the plotting notes. There are fewer than 25 pages of notes and they vary between scattered jottings and complete paragraphs. Many of the notes are reminders to amend sections already written and there is none of the plethora of ideas normally associated with the Notebooks. Note that the page numbers below do not refer to the published version but, in all probability, to the proofs.

Continue next from P.120

March 9th [1973]

P.135 Letter or money in leather wallet

P.56 Name of village or market town? Must be mentioned in first chapter?

P.75 about M.R. Car accident? Change to illness

The book was completed by May 1973 and the editor at Collins wrote diplomatically in mid-June to say that he ‘enjoyed your latest novel very much’, remarking especially on the splendid character of Hannibal the dog and the wise comments on old age. He also mooted the idea of changing the title, despite the presence of the quotation, to Postern of Death, a suggestion that obviously was not well received. Further correspondence and phone calls were needed to rectify ‘certain discrepancies’ – whether references to the war refer to the First or Second World War, exactly who killed Isaac, and the splitting of some long chapters into shorter ones. With all of this clarification it is surprising that no one spotted the impossible chronology of the Beresfords’ children. In N or M? Deborah, their daughter, is involved in war work; in Book III Chapter 16 of Postern of Fate, set 30 years later, she is described as ‘nearly 40’.

Some old friends reappear – the mysterious Colonel Pikeaway and Mr Robinson – and there are numerous references to the Beresfords’ earlier cases. They reminisce as far back as The Secret Adversary in 1922, their exploits as Partners in Crime in 1929 and their war-time spy adventure in N or M?. Oddly, although they remind each other frequently about these, neither of them mentions their most recent adventure By the Pricking of my Thumbs, a mere five years earlier. The murder method in Postern of Fate, foxglove leaves as poison, has echoes of the early short story ‘The Herb of Death’ from The Thirteen Problems. And note the reference, in Book II, Chapter 2, to the idea of taking pot-shots at departing visitors; this was the unsociable habit both of Richard Warwick, the victim in The Unexpected Guest, and Christie’s brother Monty when he settled in Devon on his return from Africa.

For even the most devoted reader of Christie Postern of Fate is a challenge. Despite its intriguing premise – ‘Mary Jordan did not die naturally. It was one of us. I think I know which’ – the book never explores this enigma in any organised way. The investigation, such as it is, consists mainly of pointless and long-winded conversations, endless reminiscences and far too many inconsequential characters. What little plot there is would have benefited from the excision of at least 100 pages, but it is doubtful if even this ruthless exercise would make any overall difference. Yet the book went into the best-seller charts within weeks of publication – and stayed there. But there can be no doubt that at this stage fans automatically bought each new title just because it was the new ‘Christie for Christmas’.

The opening of the book is almost exactly as sketched below:

Notes for Nov. 1972 and Plans

Opening suggestion for a book

Tuppence says ‘What a load of books we have.’ Starts looking at books – takes some out – looks at them – laughs – finds a letter in book shoved behind shelf. Seems to indicate a murder

This is followed by speculation about the title, with ‘Doom’s Caravan’ and a variation ‘Death’s Caravan’ leading the field and heading the following page; and by the quotation that actually appears in the book:

Book T[ommy] and T[uppence] Title?

Doom’s Caravan?

Swallow’s Nest

Postern of Fate?

Doom’s Caravan

Pass not beneath, O Caravan, or pass not singing

Have you not heard

That silence where the birds are dead yet

Something pipeth like a bird?

Pass not beneath, O Caravan, Doom’s Caravan

Death’s Caravan

In the early pages of Notebook 3 Christie considers various ideas, some of which were discarded – a homicidal spinster aunt, a woman doctor – and some adopted – the census entries, hidden papers, Regent’s Park. At this stage Mary is still a German spy.

Points

Death – accidental? – of Alexander. Horseradish picked by mistake was foxglove leaves

Digitalin – Death from Heart –

Who picked them? Who cooked them (a) Cook (b) Girl helping (c) Woman doctor? Goes round garden with one of the children. Aunt or perhaps mother of illegitimate child – who grown up as her nephew – in army or navy. Mary Robinson (governess) German girl, very beautiful, is German spy – takes plans to London – Regent’s Park – Queen Mary’s garden. Tommy by reason of some of his contacts (in N or M) – Census entries – who was in the house those 2 (?) dates

Spinster Aunt – she poisons German Mary R

Simon a school friend staying there – Recognises M.R. – pointed out to him as a woman by an Army god father or an older friend – or a foreign officer an [Australian] who in 1921 or thereabouts has a cottage a place like Dittisham [a village near Agatha Christie’s Devon home] – (Reason – papers might be hidden there)

A list of characters from Notebook 7 includes a Miss Price-Ridley, who is surely a relative of Mrs Price Ridley, Miss Marple’s neighbour in St Mary Mead; a character bearing this name does make a brief appearance in Postern of Fate. This is the sort of irritating mistake that an editor should have spotted.

Points Doom’s Caravan

People

Dorothy called Dodo – Miss Little – big woman – nicknamed The Parish Pump

Griffin – old – full of memories

Miss Price Ridley

Mrs Lupton – supports herself on 2 sticks – remembers the Parkinsons, [the] Somers – also Chattertons

Place called Hallquay [Book I, Chapter 5]

And, inexplicably, in the middle of Book III, Chapter 7, after a discussion of their adventures in The Secret Adversary and N or M?, we find Tommy and Tuppence having the following conversation. The version below, from Notebook 7, is reproduced almost exactly in the novel:

Swallow’s Nest said Tuppence ‘That’s what the house was once called.’

‘Why shouldn’t we call it that again’

‘Good idea’, said Tuppence

Birds flew from the roof over their heads

Swallows flying south, said Tommy. ‘Won’t they ever come back?’

‘Yes they’ll come back next winter through the Postern of fate’, said Lionel

This is followed by brief mention of Isaac’s death, the most casual murder in the entire Christie canon. The sang-froid with which his murder is greeted is rivalled only by the casual attitude to, not to mention the implausibility of, the shooting of Tuppence.

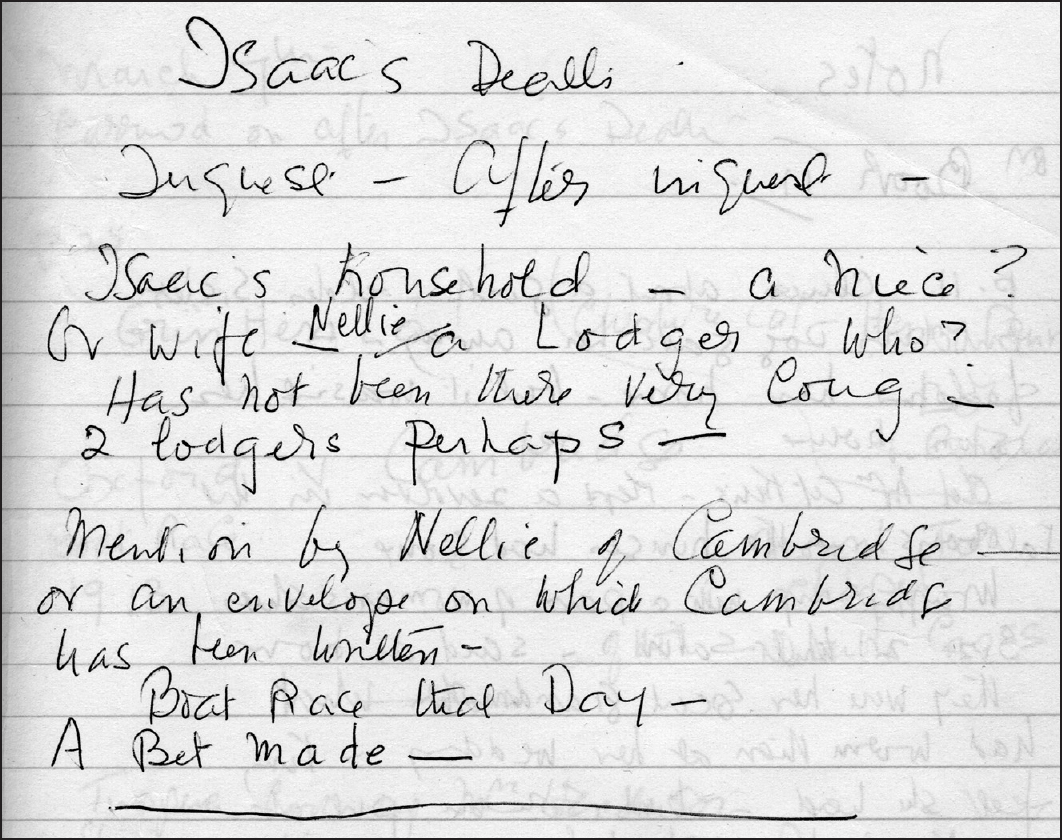

Isaacs Death

Inquest – after inquest – Isaac’s household – a niece or wife – Nellie – a lodger who has not been there very long – 2 lodgers perhaps. Mention by Nellie of Cambridge or an envelope on which Cambridge has been written – Boat Race that day – a bet made [Book II, Chapter 4]

An extract from Notebook 7 and the plotting for Postern of Fate. Note the legibility of the handwriting.

In Notebook 28 Christie considers some scenarios for the opening chapter, eventually settling on C below. The reference to Harrison Homes is to the real-life charity, providing accommodation for the independent-minded elderly, with which she was closely involved:

Large numbers of books – Tuppence is going to sort them out – take some to hospital? Or Harrison Homes – some old lady knows something

A. Is there something in a book – 2 pages stuck together B. or is there some letters or print which spell out words – a message

C. Such a sentence as ‘Mary Robinson did not die naturally. It was one of us – I think I know which one.’

This is followed by a careful working out of the code found by Tuppence in her copy of R.L. Stevenson’s The Black Arrow. The extract is from Chapter 5 of that novel and although it starts out accurately, judicious editing has been done to avoid writing out the entire extract. Eventually, isolated words only are used and sense and logic are lost, a sentiment echoed by Tommy when Tuppence shows him her discovery. Note, however, the change of the name from Robinson here to Jordan in the published version; and the incorrect spelling of ‘naturally’ as ‘naturaly’ in the code even though it appears correctly in the body of the note. Very little of this working out appears in the published novel.

The Black Arrow R. L. Stevenson

Matcham could not restrain a little cry and even Dick started with surprise and dropped the windac from his fingers but to the fellows on the lawn this shaft was an expected signal. They were all afoot together tightening loosening sword and dagger in the sheaths. Ellis held up his hand, the white of his eyes shone – let . . . . . . . the men of the Black Arrow had all disappeared and the cauldron and the ruined house burning alone to testify . . . . Not in time to warn these one from (from) upper quarters I have these I and striking I will / Duckworth and Simon red with / Is the arrow hurry ellis whistle / Space their house and dead

MARY/ROBINSON/DID/NOT/DIE/NATURALY/IT/WAS/ONE/OF//US/I/THINK/I/KNOW/WHICH/ONE

It is touching to imagine the 83-year-old Queen of Crime carefully copying and underlining her code; and to remember that it was the last ingenious idea she was to devise.