The final Unused Idea is a very special and surprising one . . .

THE EXPERIMENT

The following notes all appear in lists of ideas for both short stories and novels. The first is Idea E on an ‘A to J’ list dated January 1935, which includes the original ideas for ‘Problem at Sea’, Sad Cypress and They Do It with Mirrors.

The Experiment Mortimer – How does murder affect the character?

The following item is the first idea on a short list that includes A Pocket Full of Rye and They Do It with Mirrors, indicating a late 1940s date:

Mortimer – his plans – first killing and so on – his character gradually changes

This next jotting appears a few pages ahead of the notes for Curtain and a page of corrections for The Body in the Library, indicating a time-frame a decade earlier:

Man (or woman) who experiments in murder (goes queer)

And the final short note is probably slightly earlier, as it appears alongside notes for The Moving Finger and Sparkling Cyanide:

Mortimer – experimental murder

Although these four jottings were all written during her most productive and inventive period, it was not until the final year of her creative life that Christie elaborated on this plot. Perhaps she had been doing what she wrote of in her Autobiography, ‘looking vaguely through a pile of old notebooks and [finding] something scribbled down’; or perhaps the inspiration resurfaced from somewhere in her subconscious. The idea, as evidenced by its four Notebook appearances, was obviously one that attracted her and one that she had never tackled in any way in her published work; yet, at the time of the early notes, it would have been almost impossible for her to have attempted it with Collins Crime Club waiting for her annual ‘whodunit’. It was not until the twilight of her career that she (and they) felt comfortable publishing titles like The Pale Horse, a murder-to-order thriller with supernatural overtones, and Endless Night, a psychological suspense story with a dark secret. And this idea would have fitted into the same category.

In Notebook 7 Christie began developing the idea. Here Mortimer has disappeared, to be replaced first by Jeremy and later by Edmund:

Jeremy – discusses with friends – murders

What difference would it make to one’s character if one had killed someone?

Depends what the motive had been – Hatred? Revenge? Gain? Jealousy?

No – No motive – for no reason just an interesting experiment. The object of the crime – oneself – would one be the same person – or would one be different. To find out one would have to commit homicide – observing all the time oneself – one’s feelings, keeping notes.

Needed a victim – carefully selected but definitely not anyone that one wished dead in any way. ‘I have killed – now am I the same person I was? Or am I different – do I feel – fear? regret? pleasure? (surely not!)

People to imagine and [in]vent

The victim

Various suggestions. A woman who has cancer or a heart condition. It can suggest itself as a mercy killing.

The killer

Man? Woman? Possibly woman get excited, she too decides to try the experiment also. Man (Jeremy) does not realise what she is doing

Afterwards J finds he is excited, nervous – doctor or nurse is suspicious. J begins to lay clues of who the culprit may be and some reason why. J begins to feel he might do another murder – Lay the clues

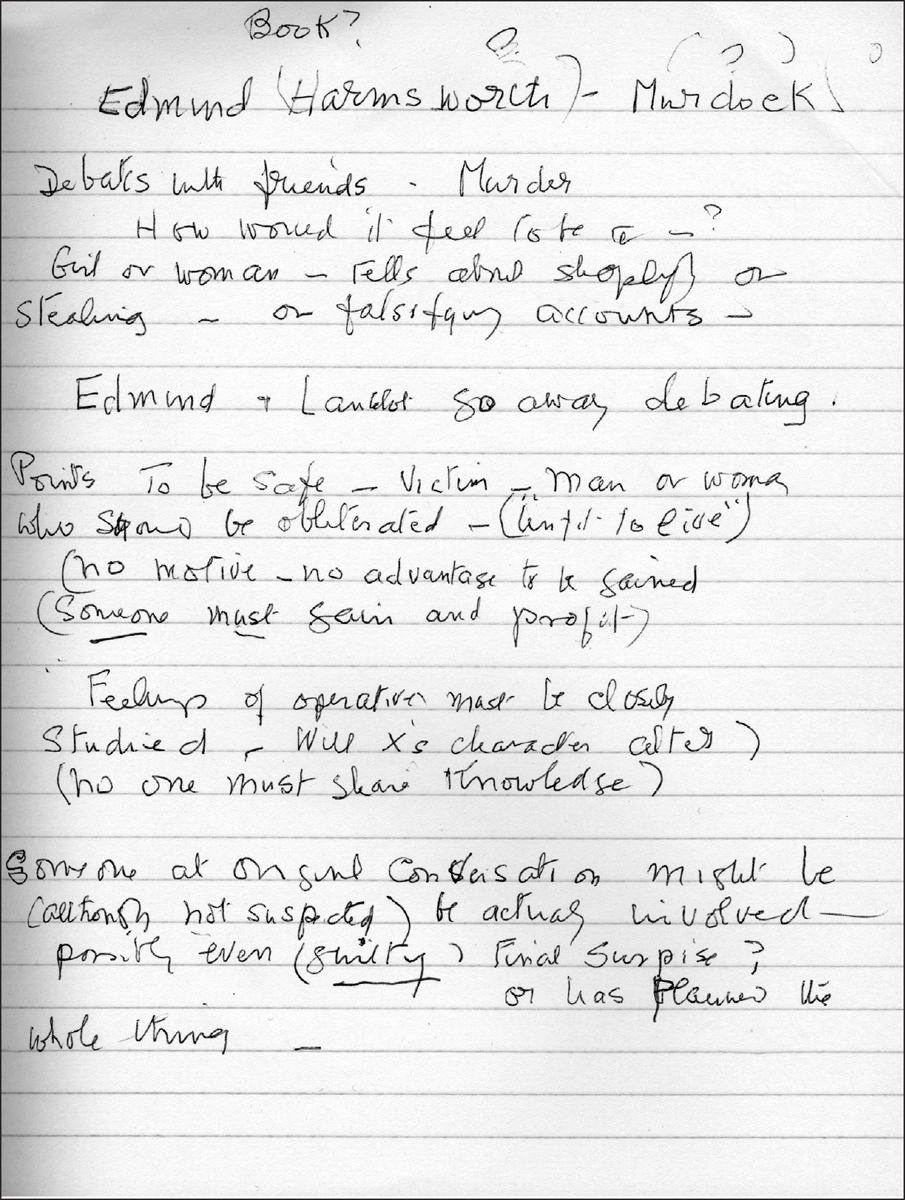

Edmund (Harmsworth) Murdock debates with friends – Murder – How would it feel to be a [killer?]

Girl or woman – tells about shoplifting or stealing – or falsifying accounts.

Edmund and Lancelot go away debating

Points to be safe – victim – man or woman

Who should be obliterated – (‘unfit to live’) (no motive no advantage to be gained) (Someone must gain and profit)

Feelings of operation must be closely studied – will X’s character alter (no one must share knowledge)

From Notebook 7 this is one of the last pages Agatha Christie wrote when she was too frail to develop this fascinating sketch into one final Christie for Christmas.

By any standard Postern of Fate, the last book that Agatha Christie wrote, is a sad end to a wonderful career. Amazingly, the notes above are for the novel to appear in 1974. The page in the Notebook immediately preceding them is unequivocally dated 7 November 1973, just after the publication of Postern of Fate. As can be seen, this outline is far superior, both in concept and approach; even the notes read better than those for Postern of Fate. Here, at the age of 83, Christie was experimenting with a novel totally different from any she had written before. Sounding somewhat similar to Meyer Levin’s Compulsion (1956), which, in turn, was based on the infamous Leopold and Loeb true-life murder case, where two college students murdered a small boy solely as an experiment, this would have been a radical departure. It seems remarkable that after the previous half-dozen weak novels Christie should be even planning something like this. Whether she had the ability, at this stage, to carry off such a demanding concept is debatable but these notes confirm, once again, that it was her powers of development, and not her powers of imagination, that were waning.

And lest there be any lingering doubt, the devious hand of the Queen of Crime is very evident in the last phrase, with its final – absolutely final – Christie twist:

Someone at original conversation might be (although not suspected) actually involved – possibly even (guilty) final surprise? Or has planned the whole thing