PALMISTRY

The art of palmistry is more truly described by its old name of cheiromancy, or divination by the hand; because this term includes all the varied lore connected with the human hand throughout the ages, instead of merely referring to the study of the lines on the palm.

How old palmistry is no one really knows. It may have originated in ancient India. The Greeks certainly studied it, and Aristotle in particular is believed to have taken much interest in it. The story goes that when travelling in Egypt Aristotle discovered a manuscript treatise on the art and science of hand-reading, which he sent to Alexander the Great, commending it as “a study worthy of the attention of an elevated and enquiring mind”.

This treatise was translated into Latin by one Hispanus, and what purported to be the book discovered by Aristotle was printed at Ulme in 1490, under the title Chyromantia Aristotelis cum Figuris. An even earlier book, Die Kunst Ciromantia (The Art of Cheiromancy), by Johann Hartlieb, was printed at Augsberg in 1475. Medieval practitioners of this art claimed that it was sanctioned by Holy Writ, quoting a text from the book of Job, Chapter 37, verse 7: “He sealeth up the hand of every man; that all men may know His work.” The original Hebrew of this passage reads “In the hand He will seal”, or “sealeth every man”; and the defenders of palmistry argued that this meant God had placed signs in men’s hands, which the wise could read and interpret.

Some churchmen agreed with this and some did not. The palmists were perhaps on safer ground when they associated palmistry with astrology, and with the doctrine of man as the microcosm or little world, in which all the correspondences of the heavens could be symbolically traced. The sun, moon and planets, together with the signs of the zodiac, were all assigned their places and governorship upon the human hand. A fragment of medieval Latin verse told the story:

Est pollex Veneris; sed Juppiter indice gaudet,

Saturnus medium; Sol medicumque tenet,

Hinc Stilbon minimum; ferientem Candida Luna

Possidet; in cavea Mars sua castra tenet.

The translation reads: “The thumb is of Venus; but Jupiter delights in the index finger, and Saturn in the middle finger, and the Sun holds the third finger (medicus). Mercury is here at the smallest finger, and the chaste Moon occupies the percussion [i.e. the outside of the hand, opposite to the thumb]; in the hollow of the hand Mars holds his camp.”

The four fingers each have three divisions, or phalanges, making twelve in all, a natural correspondence with the twelve signs of the zodiac. Thus one can in a sense clasp the whole of the starry heavens in one’s hand.

A good hand-reader had no need to cast an elaborate horoscope for his client. The horoscope was there upon the hand, formed and imprinted by nature, only requiring skill and intuition to read it. Hence practitioners from the poorer classes, like witches and gypsies, who had no expensive astronomical instruments or books for the casting of horoscopes, cultivated palmistry. “To know the secrets of the hand” is one of the powers of witchcraft mentioned in Aradia. (See ARADIA.)

The magical number seven figures largely in palmistry. There are seven chief lines upon the palm of the hand: the line of life, the line of heart, the line of head, the line of Saturn or fortune, the line of the Sun or brilliancy, the hepatica or line of health, and the girdle of Venus. There are also seven mounts upon the palm, named after the sun, moon and planets. Moreover, the famous French palmist, D’Arpentigny, who wrote in the early part of the nineteenth century, distinguished seven types of hand: the elementary hand, the spatulate or active hand, the conical or artistic hand, the square or useful hand, the knotty or philosophic hand, the pointed or psychic hand, and the mixed hand, which is a combination of several types. The terms ‘spatulate’, ‘conical’, ‘square’ and ‘pointed’ refer to the four different types of finger-tips; and they have a certain affinity with the four elements and the types of temperament they govern.

As might be expected, the four elements and the quintessence, or spirit, are also included in the general symbolism of the hand. Water belongs to the first finger, earth to the second, fire to the third, and air to the little finger; while the thumb, which to a palmist indicates the will-power of the subject, is the place of spirit.

In order to arrive at a truthful estimate of a person’s character, and therefore of their prospects, both hands must be examined and compared. The left hand will show the inherited tendencies of the subject, and the right will manifest what use the subject has made of those tendencies, and how they have been developed or modified by life. If the subject happens to be left-handed, however, the reverse will apply, as it is the active hand which shows the life of the person.

Space does not permit a detailed instruction on hand-reading here. However, many good books are today available on the subject, including those by the famous palmist Louis Hamon, who practised under the pseudonym of ‘Cheiro’. Cheiro’s work may be considered by some today to be out of date; but we owe him a considerable debt, because by his successful reading of the hands of many famous people he helped to make palmistry socially acceptable, whereas it had for many years been illegal in Britain.

Under the so-called Rogues and Vagabonds Act of 1824, in the reign of George IV, it was laid down that “every person pretending or professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any of His Majesty’s subjects” could be sentenced to three months’ hard labour. This act was sometimes held to apply to witchcraft, as well as palmistry.

PAN

Pan, the goat-footed god, is the Greek version of the Horned God, who has been worshipped under various guises since the beginning of time. In Greek, Pan means ‘All, everything’; and the various representations of Pan show him as the positive Life Force of the world.

The spotted fawn-skin over his shoulders represents the starry heavens. His body, part-animal and part-human, is living Nature as a whole. His shaggy hair is the primeval forest. His strong hoofs are the enduring rocks. His horns are rays of power and light.

The seven-reeded Pan-pipe upon which he plays, is the emblem of the septenary nature of things, and the rulership of the seven heavenly bodies. Its melody is the secret song of Life, underlying all other sound. He is beautiful, and yet able to inspire panic terror, even as the varying moods of Nature can be.

Although worshipped by the Greeks, he was never really counted among the later and more civilised gods of Olympus. His home in Greece was Arcadia, where the people were regarded as being the most primitive among the Greeks. They were farmers and hunters; and Pan was the patron god of these pursuits, away from the life of the cities. He was the lover of the nymphs of the forest, and of the Maenads, the Wild Women who took part in the Orgies of Dionysus. Dionysus himself, the horned child, was something like a younger version of Pan.

Pan was the only one among the gods to whom the virginal Artemis ever yielded. Artemis, the moon goddess, was worshipped by the Romans as Diana; and they also revered Pan, whom they called Faunus or Silvanus. Like Diana, his cult spread with the extension of the Roman Empire and mingled with that of native divinities.

There are different versions of Pan’s origin among the Greek mythographers, as there are different derivations of his name. Some regard the latter as being derived from paein, ‘to pasture’; but, considering the primitive nature of this God, and his pantheistic attributes, there seems no need to seek any other derivation than to Pan, ‘the All’. One myth of his origin says that he was the son of Hermes. This is meaningful, when we remember that the original herm was a sacred stone, a phallic menhir around which dances and fertility rites were held. Pan was then the spirit of the stone, the masculine power of life which it symbolised.

He was the power which the occult philosophers called Natura naturans, as the feminine side of Nature was called Natura naturata.

When the old pagan faith was superseded by Christianity, a legend grew up that ‘Great Pan was dead’. The sound of a great, sad voice crying this was said to have been heard over the Mediterranean Sea. But in fact, the worship of Pan and the other divinities of Nature had only disappeared for a time, and gone underground, to reappear as the witch cult all over Europe.

Pan was noted among the gods of Greece, for summoning his worshippers naked to his rites. Later, the witches who honoured the Horned God delighted in nude dances, a direct derivation from the customs of antiquity.

Two of the titles by which Pan was known to his worshippers were Pamphage, Pangenetor, ‘All-Devourer, All-Begetter’, that is the forces of growth in Nature, and the forces of destruction. Nothing in Nature stands still. All is constantly changing, being born, flowering, dying and coming again to birth. The same idea is seen in the Hindu concept of the god Shiva, who is both begetter and destroyer. By the Lila or love-play of Shiva and his consort Shakti, all the phenomena of the manifested world are brought into being. But Shiva is also the Lord of Yoga, the means by which men can find their way beyond the world of appearances, and discover the numinous reality. Even so, the concept of Pan was really something more profound than the jolly, sensual god of primitive life that he is usually taken to be.

However, he was primarily a god of kindly merriment, worshipped with music and dancing. Dancing and play are a basic activity of all life. Children are natural dancers, and so are animals. Forest creatures leap and gambol in the woodland. The mating dances of birds, the amazing springtime antics of hares, even the constant circling of a swarm of gnats on a summer evening, all are part of the same instinctive impulse. The earth, the moon and all the planets join in a great circling dance about the sun. The island universes of the nebulae seem to be circling about a centre. The merry circle dance of the witches was a deeply instinctive response to the living Nature with which they sought kinship.

The medieval Church had ceased to be able to comprehend a religion which sought to worship the gods by dancing and merriment. The idea was growing among Churchmen that anything enjoyable must be sinful. We are still suffering from this strange aberration of human thought today; although humanity is beginning at last to emerge from the Dark Ages—much to the indignation of those who rage against what they call the ‘permissive society’.

It was this dark view of human life, the regarding of pleasure as sinful, which in turn darkened the survivals of paganism in Europe. The merry goat-footed god became ‘the Devil’, and the witches who worshipped him were forced into secret association, an underground movement beset by fear and suspicion, and with the torture-chamber, the gallows or the stake constantly in the background.

We tend to think of medieval times as being colourful, picturesque, and rather gay, with rosy-cheeked peasants dancing round the maypole, and so on. In practice, they were days of fear, suffering and oppression; and much of the colour and gaiety of olden days, like the art and learning of the Renaissance, was either the survival or the revival of paganism. If we look at the beautiful figures of Pan which have survived from Greek and Roman Art, and contrast them with the twisted, leering, horned demons of medieval times, we can see this change of vision and attitude mirrored in the artforms, which are the visual expression of men’s souls.

PENTAGRAM, THE

The pentagram, or five-pointed star, is a favourite symbol of witches and magicians. It has been so widely used throughout the centuries that the word ‘pentacle’, also originally meaning a five-pointed star, has come to designate any disc or plate of metal or wood, engraved with magical symbols, and used in magical rites.

The origin of the magical five-pointed star is lost in the mists of time. Early examples occur in the relics of Babylon. The Christians regarded it as representing the Five Wounds of Christ, and hence it is sometimes found in church architecture. There is a very beautiful form of a pentagram in one of the windows of Exeter Cathedral.

This sign also occurs among the emblems of Freemasonry. Some regard it as being the Seal of Solomon; though this designation is more often given to the six-pointed star, formed by two interlaced triangles, which is the sign of the Jewish faith. However, the pentagram is certainly a Qabalistic sign, known to those occult fraternities which claim to derive from the Rosicrucians.

The followers of Pythagoras called the pentagram the pentalpha, regarding it as being formed of five letter A’s. In medieval Europe it was known as ‘The Druid’s Foot’, or ‘Wizard’s Foot’; and sometimes as ‘The Goblins’ Cross.’ In the old romance of Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight, it is the device which Gawaine bears on his shield.

It also occurs in the old song ‘Green Grow the Rushes-O’. This curious old chant of questions and responses contains hints of hidden meanings; and one of its lines is “Five is the symbol at your door” meaning the pentagram, which was inscribed on doors and windows to keep out evil.

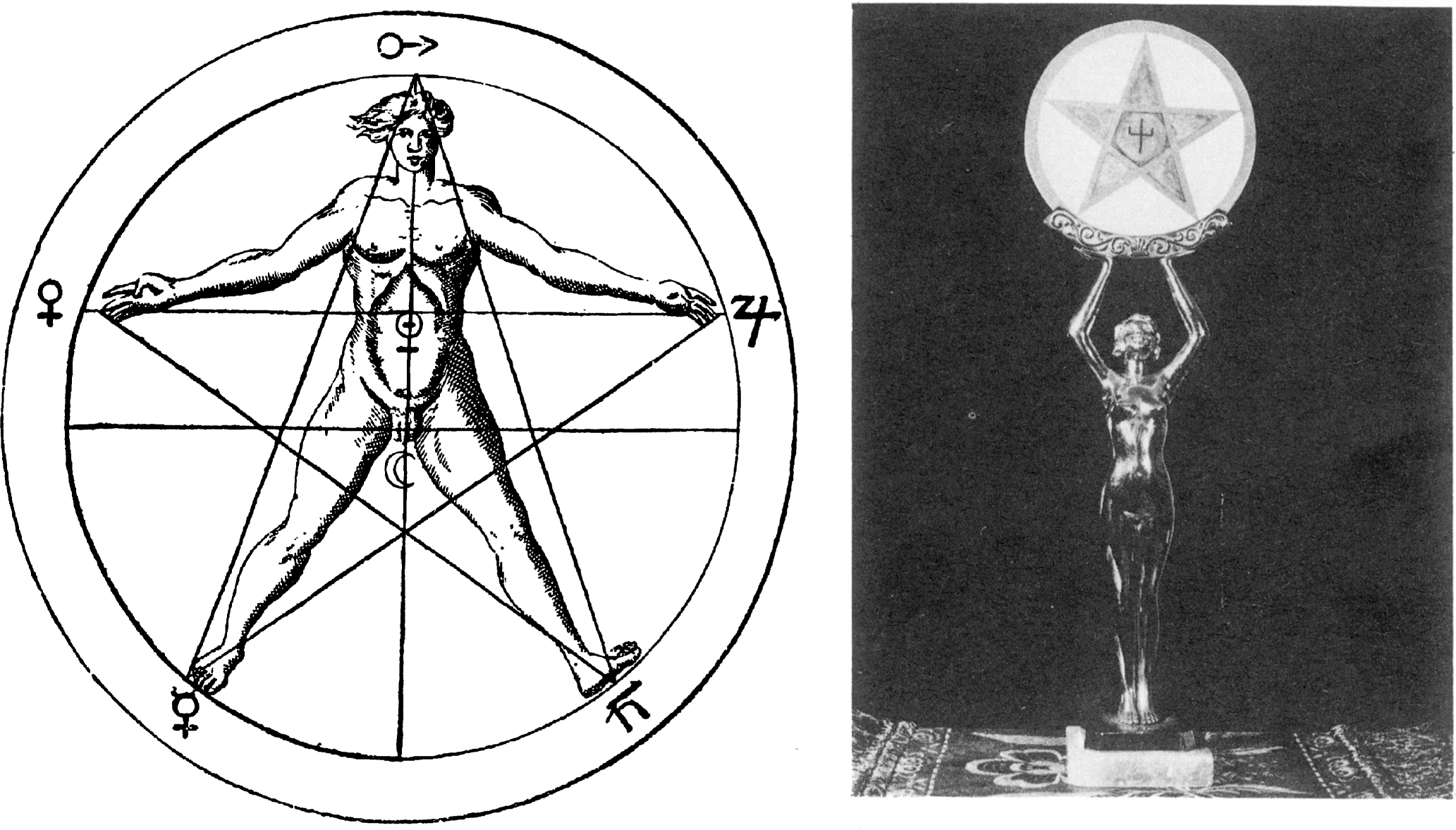

PENTAGRAM, THE. (above left) Man the microcosm, the pentagram of Cornelius Agrippa. (above right) The pentagram from a modern witch’s altar.

Some old Celtic coins show the figure of a pentagram upon them. Something very like the five-pointed star occurs naturally upon some fossils, and these objects have always been prized by witches for this reason, as being highly magical. One kind of fossil with a five-pointed figure upon it is the so-called shepherd’s crown, a fossil sea-urchin. (See FOSSILS USED AS CHARMS.) But an even more potent magical object than this is the true star stone, a fossil which occurs in the perfect shape of a five-pointed star. It is actually part of the fossilised stem of a Crinoid or sea lily.

The reason why the pentagram is regarded as the symbol of magic is because its five points represent the Four Elements of Life, plus Spirit, the Unseen, the Beyond, the source of occult power. For this reason, the pentagram should be drawn with one point upwards, the point of Spirit presiding over the other four. It is Mind ruling over the World of Matter.

The other way up, the pentagram is often regarded as a more sinister symbol. According to Madame Blavatsky, in her Secret Doctrine (Theosophical Publishing Co., London, 1888), the reversed pentagram is the symbol of Kali Yuga, the Dark Age in which we live, an age of materialism, sensuality and violence. Other occultists have regarded the reversed pentagram as the face of the Goat of Mendes, with the two upward points representing the goat’s horns. In this sense, it is the face of the Horned God. It has sometimes been called a symbol of black magic; but what it really represents is the light of the Spirit hidden in Matter.

The pentagram with one point upwards is used by occultists to control elementals, because of its inner meaning. Worn as a lamen upon the breast, it is a protection in magical rites, against hostile or undesirable influences.

It is sometimes called the Star of the Microcosm, because it has the shape of a human being with arms and legs outstretched. The old occult philosophers regarded man as a microcosm, or little world in himself, containing in potentiality all that was in the cosmos without him. The pentagram also represents the five senses of man, the gateways by which impressions of the outer world reach him.

Yet another name for the pentagram is the Endless Knot, because it can be drawn without lifting the pen from the paper, though it requires concentration and care to draw a symmetrical figure in this way; qualities which were necessary for the successful making of a magical sign.

PERSECUTION OF WITCHES

The law making witchcraft a capital offence in England was repealed in 1735. For some years previously, enlightened judges had been thwarting any attempt to have wretched old creatures hanged as witches, in spite of popular outcry against them. The more educated people of the nation had become sickened at the superstition and imposture connected with trials for witchcraft. The pendulum had swung completely the other way, so that many now completely disbelieved in witchcraft at all.

PERSECUTION OF WITCHES. Woodcut showing the ‘swimming’ of witches from the pamphlet, “Witches Apprehended, Examined and Executed” published in London in 1613 (reproduced by courtesy of the Bodleian Library, Oxford).

This attitude, however, was by no means shared by the less educated classes. They still vehemently believed in witchcraft, both black and white, and moreover believed that witches who worked harm should die, or at any rate suffer severely. So when the law of the land was relaxed, lynch law sometimes took over.

The self-styled ‘wise woman’ or ‘cunning man’ often played a very sinister part in these proceedings. At that time (as now) there were many clever and greedy impostors, who made a good living out of public credulity. One of their specialities was pointing out dangerous witches, with profit to themselves, and sometimes a tragic and fatal result to some unfortunate old man or woman whom they picked on.

A sensational case of this kind occurred at Tring, in Hertfordshire, in 1751, when a poor old couple, John and Ruth Osborne, were attacked by a mob, and Ruth Osborne died as a result.

They may well not have been witches at all; but a man called Butter-field had got it into his head that they were, on account of some ill-health and misfortune he had encountered, after quarrelling with Mrs Osborne.

He accordingly sent as far as Northamptonshire, for a renowned wise woman to come and help him. She confirmed that he was be-witched, but her services proved both expensive and without result, so far as improvement in Butterfield’s affairs was concerned. However, curiosity and excitement had by now been aroused in the neighbouring countryside; and someone caused the public criers of three adjoining towns, Hemel Hempstead, Leighton Buzzard, and Winslow, to make this announcement: “This is to give notice, that on Monday next, a man and woman are to be publicly ducked at Tring, in this county, for their wicked crimes”.

When the parish overseer of Tring learned that the Osbornes were the people referred to, he lodged them for their own safety in the work-house. They were again moved from there to the vestry of the parish church, late on the Sunday night.

On the Monday morning, a mob, estimated at over 5,000 persons, many of them on horseback, assailed the workhouse, demanding the Osbornes. When the workhouse master told them the couple were not there, the mob rushed in and searched the building. Baulked of their victims they then turned on the wretched workhouse master, and threatened him with death if he did not reveal where the Osbornes were.

Having discovered by this means that the supposed witches were hidden in the church, the mob broke open the church doors, seized John and Ruth Osborne, and dragged them to a pond at Long Marston.

Here they were both stripped naked and wrapped each in a sheet. Their thumbs and great toes were tied together, and a cord was put round each one’s body, precisely as witches had been ‘swum’ in Matthew Hopkins’ time. Each suspect was then separately thrown into the pond. When Ruth Osborne seemed to float somewhat, a man named Thomas Colley pushed her down with a stick. This treatment was three times repeated in each case, and one account says that the prisoners were then laid naked on the shore, where they were kicked and beaten until Ruth Osborne was dead and her husband nearly so. Thomas Colley then “went among the spectators and collected money for the pains he had taken in showing them sport”; so the account of his subsequent trial tells us.

Neither the local clergy nor the magistrates had raised a finger to save the Osbornes. However, a riot of such proportions, and its fatal consequence, could not be hidden; and many people were indignant and horrified. A coroner’s inquest was held upon the death of Ruth Osborne; and twelve of the principal gentlemen of Hertfordshire were summoned to form the jury, because at an inquest held in a similar case a short time before, at Frome in Somersetshire, the jury had refused to bring in an obviously justified verdict of murder.

The result was that Thomas Colley was in due course tried for the murder of Ruth Osborne at the County Assizes. John Osborne had recovered, but did not appear to give evidence. Nevertheless Colley was found guilty, and sentenced to be hanged. On the scaffold, a solemn declaration of Colley’s faith relating to witchcraft was read for him by the minister of Tring. A strong military escort accompanied him to the scaffold, on account of the public sympathy for him, and a good deal of grumbling among the people “that it was a hard case to hang a man for destroying an old wicked woman that had done so much mischief by her witchcraft.”

This was the most notorious case of mob violence against alleged witches in England; but by no means the only one. There are many recorded instances of people attacking those they accused as witches, and trying to ‘swim’ them or ‘draw blood upon them’. The latter is another very old belief, that if you can strike a witch so as to draw blood, these lose their power over you. It has been responsible for a number of deaths, notably those of Nanny Morgan in Shropshire in 1857, and Ann Turner in Warwickshire in 1875.

Both these women were killed by men who believed themselves bewitched by them. Nanny Morgan, who lived at Westwood Common, near Wenlock, belonged to a witch family. The old country saying was applied to her kinsfolk, “that they could see further through a barn door than most”. The method of her death dated back to Anglo-Saxon times, when it was called pricca, meaning staking down the suspected witch with a sharp weapon, so that the blood flowed. Nanny Morgan was found in her cottage, pinned down with an eel spear through her throat.

That she did actually practise witchcraft was proved by the fact that a number of letters were found in her cottage, some from people of eminent local position, asking for her services. There was also a box of gold sovereigns, which she had apparently accumulated by the practice of occult arts. Witches today believe that it is wrong to practise witchcraft for money, and that it ultimately brings retribution upon the person who does so.

The young man who killed her had been a lodger in her house. He had wanted to leave, but was too afraid of her to break away. In the end he committed this desperate act.

Ann Turner was killed in the village of Long Compton, near the Rollright Stones; a village which, like Canewdon in Essex, has a strong local tradition of witchcraft. A young man, who believed she had bewitched him, attacked her with a hayfork. He may only have meant to draw blood upon her; but she was an elderly woman, and she died of her injuries.

A contemporary account has come down to us, of a similar case in Wiveliscombe, Somerset, in 1823, which fortunately did not end in murder, but came very near to doing so. This case is notable, for the way in which it illustrates the part that a ‘cunning man’ often played in these matters. This supposed protector against black witchcraft was one Old Baker, known as the Somerset Wizard.

Three women named Bryant, a mother and her two daughters, had consulted him because one of the girls was thought to be bewitched. He, of course, confirmed that this was so, and sold the mother some pills and potions for the girl to take, and also a mysterious packet of herbs. The actual prescription, in Old Baker’s illiterate hand, read as follows: “The paper of arbs [herbs] is to be burnt, a small bit at a time, on a few coals, with a little hay and rosemary, and while it is burning, read the two first verses of the 68th Salm, and say the Lord’s Prayer after”.

After Old Baker’s instructions had been carried out, the daughter had no further fits of supposed possession. But one thing remained to do; blood must be drawn upon the witch, to break her spell for ever. Mrs. Bryant told a neighbour “that old Mrs. Burges was the witch, and that she was going to get blood from her.”

In the meantime, old Mrs. Burges had heard what she was being accused of, and went to Mrs. Bryant’s house to confront her and deny the charge. Fortunately for her, she took a woman friend with her, whose exertions saved her life. The three Bryant women fell upon the old lady, and two of them held her down, while the third, the allegedly bewitched daughter, attacked her. They cried out for a knife, but none being handy, they used the nearest weapon, a large nail, with which they lacerated her arms.

The woman who had accompanied Mrs. Burges cried “Murder!” A mob soon assembled round the door of the house; but they did nothing to stop the ‘blooding’, saying that the old woman was a witch. By the time her friend had dragged her away from her attackers, Mrs. Burges had sustained fifteen or sixteen wounds, and was bleeding severely. She was taken to a surgeon, who dressed her injuries; and as a result of the affray, the Bryants found themselves summoned before a judge at Taunton Assizes.

Here the whole story came out, including the part played in it by Old Baker; of whom the judge observed, “I wish we had the fellow here. Tell him, if he does not leave off his conjuring, he will be caught, and charmed in a manner he will not like.”

All three of the accused were found guilty, and sentenced to four months’ imprisonment.

The belief in drawing blood on a witch was still lively in Devonshire 100 years later. In 1924 a Devonshire farmer was prosecuted for assaulting a woman neighbour, whom he accused of afflicting him by witchcraft. He had scratched her on the arm with a pin, and threatened to shoot her. The man insisted in court that the woman had ill-wished him and bewitched his pig. This was why he had tried to draw blood on her. He wanted the police to raid the woman’s house and take possession of a crystal ball, which he said she used in her spells. Nothing the magistrates said would make him change his belief; and he was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment.

It might be supposed that the flourishing technological society of modern Germany, after two World Wars, would have changed to such an extent that the days of witch persecutions would be quite forgotten. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the 1950s German newspapers carried frequent reports of the activities of ‘witch-exorcists’–activities which sometimes ended in the death of the person they accused of being a witch.

In 1951 Johann Kruse founded in Hamburg The Archives for the Investigation of Witchery in Modern Times. In the same year Herr Kruse published a startling book, entitled Witches among Us? Witchery and Magical Beliefs in Our Times (West Germany, 1951). This book revealed facts about the continuing belief in witchcraft in Germany, which amazed his contemporaries.

The West German newspaper in 1952 reported no less than sixty-five cases involving witchcraft. Many of them were so horrible that it seems incredible they were printed in the columns of a modern newspaper, and not in some centuries-old black-lettered book.

For instance, there was the case of a young woman who was admitted to hospital at Haltern, three weeks after her wedding. She was dying; but before she expired she was able to tell how she came by her injuries. It appeared that just after her marriage an outbreak of some cattle disease had occurred on the farm of her husband’s parents. A woman from Gelsenkirchen, who was a so-called soothsayer, had declared that the new bride was a witch, and responsible for the disease among the cattle. At the soothsayer’s instigation, the family had imprisoned the poor girl in a dark room, where she was slowly done to death by starvation and beatings.

These self-styled ‘soothsayers’ or ‘witch-exorcists’, although professing to practise “white magic”, in fact recommended the most revolting cruelties against both humans and animals, in their war against witchcraft. The idea very often was (one hopes that the past tense is appropriate, though this is doubtful), that if they could not torture the witch, the ill-treatment of an animal would somehow be conveyed to her.

Thus, a remedy for headaches supposedly caused by witchcraft was to tear a live black cat in two and lay the bloody remains upon the patient’s head, where they must stay for three hours. The remedy for hens who were allegedly bewitched by the Evil Eye was to burn two hens alive in an oven. This was actually done, on the advice of a ‘witch-exorcist’, and reported in a German newspaper in May 1952.

Another practice recommended by the ‘de-witchers’ was the profanation of graves. Bones gathered from churchyards were sought for as a protection against bewitchment; and a prescription against fever (probably thought to be witch-induced) was: “Take human bones from three different graveyards, reduce them to charcoal, and give them, pounded to a powder, to the patient with brandy.”

Other ‘de-witching remedies’ consisted of asafoetida—which is an evil-smelling gum-resin popularly known as ‘Devil’s dung’—horse dung and urine; and even human urine, which one ‘witch-exorcist’s’ patients were induced to drink—at three marks a bottle!

Sometimes, among all this welter of filth and horror, there appeared a glimpse of a real memory of the ancient witchcraft. In the province of Hamburg, for instance, a peasant who believed his house was bewitched got his family to strip themselves naked every night, and sweep the floors with brooms, to drive the evil influence away, Knowingly or not, he was in fact carrying out an old witch rite, of being in a state of ritual nudity, and symbolically sweeping away evil, one of the things that a witch’s broomstick is actually used for.

The authorities in Germany took notice of Herr Kruse’s revelations, and in subsequent years several of these modern witch-finders were brought to trial and punished for their crimes and their defamation of innocent people. A book often mentioned in the course of these trials is the so-called Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, or Moses’ Magical Art of Spirits, which was a favourite of the ‘witch-exorcists’. As a result, the sale of this book was banned in Germany. However, I have a copy in my own magical collection. (English translations have appeared in U.S.A., often clandestinely, without date or publisher’s name). What it purports to be is the secret Words of Power which Moses used, and the signs and symbols which accompany them, which give the operator power over evil spirits. It is not a book of witchcraft, but derives from the darker side of ceremonial magic.

History shows us that the witch-finder expresses the loftiest motives; but at the same time his hand is always held out to receive money.

PHALLIC WORSHIP

It is only in comparatively modern times that the real nature of much ancient religious symbolism has been able to be publicly discussed. The idea that people used the attributes of sexuality to represent something holy, was so shocking—to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in particular—that books which treated this subject, in however scholarly a manner, were sold from under the counter.

Nevertheless, it seems a very natural thing that the means of the transmission of life should represent, in the deeps of man’s mind, the unknown and divine source of that life.

This has been recognised in the East since time immemorial, and the Sacred Lingam, or phallus of Shiva, has been worshipped in India as the emblem of the Life Force, without any embarrassment or idea of ‘obscenity’. Until, that is, the civilised white man arrived, and usually either sniggered or was horrified, according to his temperament.

In years long past (and in some places not so long past), however, Western Europe also revered the cult of the phallus and its female counterpart, the cteis or yoni. Indeed, it was the phallic element in the Old Religion of witchcraft, which the Christian Church found particularly abominable.

Old pictures and woodcuts of the Devil, either presiding over a dance of witches, or going about the countryside looking for mischief, nearly always represent him with huge sexual organs prominently displayed. It is notable also, how the interrogators of witches, usually clerics, were always very interested in getting a detailed description of the Devil’s sexual organs, from the person they were putting to the question. Nor would they be satisfied without an intimate account of what sexual relations the Devil had with his followers.

Most of this was the excited and prurient curiosity of enforced celibates; but perhaps not all of it. The more learned churchmen, who had read the classical authors’ accounts of pagan worship, may well have realised that the artificial phallus had a definite religious significance. They were looking for survivals of the old pagan fertility cults; and they well knew that witchcraft was a continuation of these cults.

The jumping dance that witches performed, with a broomstick between their legs, was an obviously phallic rite. It was done to make the crops grow taller; and it had the same idea behind it as that which caused the Greeks and Romans to place in their gardens a statue of Priapus, the phallic god, with an enormous genital member, as magic to make the garden grow.

The phallus was also a luck-bringer, and an averter of the Evil Eye. In the latter role it was sometimes called the fascinum, because it was supposed to exercise the power of fascinating the sight, and drawing all glances to it; which was not a bad piece of practical psychology. People cannot help being interested in sex. Even prudery is only an inverted form of being fascinated by sexual matters.

Many little amulets or charms in the form of phalli have been found. They were made to hang around the neck usually; though some are in the form of brooches. Two specimens, which I have in my own collection of magical objects, illustrate the antiquity and widespread nature of the phallic cult. One is from Ancient Egypt, and is made of green faience. It is the form of a little man with an enormous genital member; and this amulet is made to hang around the neck.

The other was obtained a few years ago in Italy. Also to hang around the neck as a lucky charm, it is a good replica of an old Etruscan original, a winged phallus. I was told that these definitely pagan amulets, while not on public sale, are nevertheless quite easily obtained, and very popular. Their power to bring good fortune and avert the Evil Eye is still very definitely believed in.

In Ancient Rome the consecrated effigy of a phallus was regarded as bestowing sanctification and fertility, in certain circumstances. Thus a Roman bride sacrificed her virginity upon the life-sized phallus of a statue of the god Mutinus. Also, in the ancient world, and particularly in Egypt, statues of the gods of fertility were often made with a removable phallus, which was used separately in rituals designed to invoke the powers of fertility.

We are reminded of these ancient rites of a simpler age, when we read the many stories of the ‘Devil’ who presided over the witches’ Sabbat having intercourse, or simulating intercourse, with the many women present, by means of an artificial phallus, which was part of his ‘grand array’, along with the horned mask and costume of animals’ skins.

This rite was not done simply for sexual gratification; and the inquisitors who examined suspected witches knew it was not. The reason for its performance goes back a very long way into ancient history.

Of course, the published accounts of it were deliberately made as repulsive and horrifying as possible; because the Sabbat had to be represented in the Church’s propaganda in such a way that people would not wish to go to it. However, the very repulsiveness of these accounts defeats its own ends; because if the witches’ Sabbat was really as vile, agonising, filthy and generally repellent as the Church propagandists alleged, why on earth would anyone attend it, when they might be safe and warm in their beds? Yet we are informed that many people, particularly women, did.

It is amusing to note, as Rossell Hope Robbins has pointed out in his Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (Crown Publishers Inc., New York, 1959), that most of the earlier accounts of the Sabbat declare that it included a sexual orgy of the most voluptuous and satisfying kind. Women, it was said, enjoyed sexual relations with the Devil “maxima cum voluptate”. Then, in the latter part of the fifteenth century, someone in the Church’s propaganda seems to have realised that this was not the sort of public image of the Sabbat that helped the Church’s cause. So from that time on, the published stories of the Sabbat change. Intercourse with the Devil is said to be painful and horrible and only submitted to by force and with reluctance.

One feature in common, that nearly all the accounts possessed, was the statement that the Devil’s penis was unnaturally cold. It was this that caused Margaret Murray to speculate, in her writings about the witch cult, that an artificial phallus was used in many cases.

Montague Summers, in his History of Witchcraft and Demonology (Kegan Paul, London, 1926, reprinted 1969), agrees with Margaret Murray’s findings in this respect; though of course he goes on to hint that there were darker mysteries still, of demonic materialisation. However, he tells us significantly that the use of artificial phalli was well known to ‘demonologists’, and regarded by the Catholic Church as a grave sin. It is frequently mentioned in old Penitentials.

Representations of the phallus may be seen in the curious round towers attached to certain Sussex churches, notably the one at Piddinghoe. These are reminiscent of the round towers of Ireland, which antiquaries have long considered to be phallic monuments. There are some seventy or eighty of these towers to be found in Ireland, and no one knows who built them, or what their purpose was, though their phallic shape is self-evident. Some of them are over 100 feet in height. All are of great antiquity; so old, in fact, that some are supposed to be sunk beneath the surface of Lough Neagh, becoming visible beneath the waters when the weather is calm. Some famous sites of round towers are those at Glendalough, Ardmore, and upon the Rock of Cashel.

The beauty and mystery of these strange old monuments is another link with that basic worship of life which lies at the root of all ancient faiths.

Other instances of phallic symbolism are the tall, solitary standing stones called menhirs. A number of these ancient sacred stones may still be seen in Britain. For instance, at Borobridge in Yorkshire is a huge phallic monolith called The Devil’s Arrow. In the same county at Rudston, one of the finest phallic menhirs still surviving may be seen standing next to a Christian church. The place-name of Rudston comes from the old Norse hrodr-steinn, ‘the famous stone’. As the stone is much older than the church, the latter must have been deliberately built there, as a confrontation between the old faith and the new.

(See also FERTILITY, WORSHIP OF.)