TAROT CARDS

These mysterious cards are today popular with occultists of many schools for the purpose of divination. They are also regarded as containing mystical and magical secrets, for those who can discern them. However, before the Tarot reached its present-day level of general interest, it was preserved among the gypsies, and also among their frequent companions in hardship and misfortune, the witches.

Grillot de Givry, in his Pictorial Anthology of Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy (University Books, New York, 1958), bears witness to the fact that, in France at any rate, and probably elsewhere on the Continent, the Tarot cards were part of the magical armoury of the village witch. Before the days of fashionable Society clairvoyants, ladies of rank and wealth who wanted their fortunes told would go secretly to consult the wise woman in her tumbledown cottage. Later, her place was taken by such elegant practitioners as Mademoiselle Le Normand and Julia Orsini. The former lady is famous for the consultations she gave to Napoleon and Josephine by means of the divining cards.

When the Tarots arrived in England is not known, but there are records to prove that cards were imported here from Europe before 1463.

As for the Gypsies, they had for so long borne the Tarot pack with them in their wanderings that many people believed the Tarot to be of gypsy origin. Hence it was sometimes called ‘The Tarot of the Bohemians’. Others have cast doubt on this, saying that the cards were known in Europe before the gypsies arrived here from the East. The generally accepted date for the gypsies’ first appearance in Europe is 1417; and Tarot Cards were known before then. However, some experts on gypsy lore would dispute this date also, saying that gypsies were in Europe before that time; so the enigma remains. No one really knows the origin of the Tarot.

The gypsies themselves claim to see in some of the pictures on the cards, the sad history of their wanderings and persecutions. They derive originally from India, and their language, Romany, has links with the Hindu tongue. Now, it is certainly true that playing cards, and very elaborate and beautiful ones, are known in India and the East generally, and in Tibet. In the latter country, before it came under Chinese Communist rule, cards were produced which were not only intended for gaming, but bore pictures associated with the Tibetan religion. Even so, although the Tarot cards can be used to play games, and were so used sometimes in olden days, their significance is obviously deeper than this.

Records exist of artists being paid to execute beautiful hand-painted Tarot packs for the diversion of kings and the nobility; and a few examples of such cards remain in museums. Also, we find very crude and quaint-looking old packs, produced in the early days of printing, for sale among the poorer classes. These cards, printed from wood blocks, often have a good deal of charm. In order to keep them flat, such old-fashioned packs of cards were kept in a little miniature press, when not in use.

The Tarot cards are the ancestors of our playing cards. Like them, the Tarots have four suits; but they also have a fifth suit the Trumps, or Major Arcana, and it is these latter which are the cards bearing the mystic pictures. There are twenty-two of the Major Arcana; and each of the four suits has fourteen cards, namely the ace to ten, and a mounted figure, the Knight, in addition to the usual court cards of King, Queen and Knave. Thus the Tarot pack consists of seventy-eight cards. This is the usual number; though there are found examples of augmented Tarots, like the Minchiate of Florence, which has 97 cards; and also of shortened Tarots, such as the Tarot of Bologna, which has only sixty-two cards.

Our pack of playing cards has discarded all the Trumps except one, The Fool, which has survived as the Joker. Also, it has lost the four Knights from among the court cards; and it has made the cards double-headed, so that they look the same either way up, for convenience in playing games. The Tarot cards, and many of the old playing-cards, are not like this, but are actual little pictures.

The playing-card suit symbols also, have been simplified from the grander emblems of the Tarot. The four suits of the Tarot cards are Wands, Cups, Swords, and Coins or Pentacles (the latter in this sense meaning a round disc with a magical sigil upon it).

The gypsies have their own names for the four suits. They call them Pal (the Wand), Pohara (the Cup), Spathi (the Sword), and Rup (the Coin). Pal could be from the same Sanskrit origin as ‘phallus’. Pohara is reminiscent of the Celtic pair and the English Gypsy pirry, both meaning a cauldron. Spathi is possibly from the same root as espada (Spanish) and epée (French), meaning a sword. Rup is like English gypsy ruppeny, meaning silver, and, of course, the Hindu rupee.

What is particularly significant about these suit symbols is that they are the four Elemental Weapons or tools of magic. The Wand, the Cup, the Sword and the Pentacle, or their equivalents, lie upon the altar of every practising magician. Their usual elemental attributions are fire for the Wand, water for the Cup, air for the Sword, and earth for the Pentacle.

Moreover, a correspondence may be found between these four Tarot emblems and the Four Treasures of the Tuatha De Danann, the divine race of the Gaels, who arrived in ancient Eire untold centuries ago, as Celtic legend tells us. This race of gods had dwelt in four mystic cities, Findias, Gorias, Murias and Falias; and from each city they had brought a treasure. There was the fiery Spear of Lugh; the Cauldron of the Dagda; the Sword of Nuada; and the Stone of Fal, which became known as the Stone of Destiny, because the ancient Irish kings were crowned upon it. The story goes that this is that very Stone of Destiny which now forms the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey. The whereabouts of the other three treasures is unknown.

In the later Grail romances, the Four Talismans appear again, in another guise of myth. They become the blood-dripping Lance, the Grail Cup itself, and the Sword and Shield bestowed upon the knight who set out in quest of it.

To the student of the Qabalah, they are the four letters of the Divine Name, the Tetragrammaton. The whole Tarot can, in fact, be arranged to form the figure of the Qabalistic Tree of Life, The real Qabalistic attributions of the Tarot cards were long kept a profound secret, in the occult fraternity known as the Order of the Golden Dawn; and it has been only in comparatively recent years that Dr. Francis Israel Regardie has published this information fully and accurately. (The Golden Dawn by Israel Regardie. Second Edition, Hazel Hills Corporation, U.S.A., 1969).

Aleister Crowley published a most elaborate volume upon the Tarot, entitled The Book of Thoth (privately printed by the Ordo Templi Orientis, London, 1944). His version, however, is an individual one, many of the old designs of the cards being adapted to suit his own magical ideas.

A popular version of the Tarot pack is that which was drawn by Pamela Coleman Smith to the designs of A. E. Waite. The figures of this Tarot have something of the air of Art Nouveau. Waite was a member of the Golden Dawn, and although sworn to secrecy, he introduced many subtleties into the designs which accord with the attributions given to the cards by that famous magical Order.

Many, however, prefer the older version of the Tarot cards, of which probably the best example is the Tarot de Marseilles. This can still be obtained today.

The numbered series of the Major Arcana or Trumps of the Tarot runs as follows: the Juggler; the Priestess (or Female Pope); the Empress; the Emperor; the Pope; the Lovers; the Chariot: Justice; the Hermit; the Wheel of Fortune; Strength; the Hanged Man; Death; Temperance; the Devil; the Tower; the Star; the Moon; the Sun; Judgment; the World; and the unnumbered card, the Fool.

The pictures and personages they show are strange and enigmatic. Occultists of various schools have written thousands of words in their interpretation; some wise and some otherwise. The Tarot is a book without words. It speaks in the universal language of symbolism. It is equally at home in the gypsy caravan, the witch’s cottage, or the splendidly-appointed private temple of the ceremonial magician. It can be used upon the level of fortune telling, or upon that of the High Mysteries. Some derive its origin from Ancient Egypt; it remains one of the real wonders and secrets of the world.

Witches see in the Tarot a relationship at any rate with their own traditions. Their Horned God is shown (especially in the older versions) upon the card called the Devil. The Goddess of the Moon appears as the Priestess. The Hermit can be interpreted as the Master Witch, passing on his way unknown, carrying the lantern of knowledge. The Wheel of Fortune is also the wheel of the year, equally divided by the Greater and Lesser Sabbats. The Hanged Man can be understood by the witch as he is by the gypsy, as the symbol of suffering and persecution. Nature in perfection, naked and joyous, is pictured upon the card called the World; and so on.

As a means of divination, the Tarot can often be startlingly accurate; on other occasions it may refuse to speak at all. As in all psychic matters, much depends upon the individual gifts of the diviner, and the conditions prevailing at the time.

TORTURE USED ON WITCHES

The above entry in this book is one that the writer has approached with reluctance. Were I to tell the full and detailed story of how the supposed followers of the Christian God of Love have smeared their bloodstained hands over the pages of human history, I would be accused of anti-Christian prejudice. Yet every detail of such an accusation could be supported by documentary evidence, in sickening abundance. Its cumulative effect would be to prove that Christianity has inflicted far more martyrdoms than paganism ever did.

Such documentation has been admirably done, sometimes with photographed copies of the originals, by Rossell Hope Robbins, in his Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1959). This book is surely one of the most damning indictments of the Christian Church ever penned; the more so as it is not written for any such purpose but simply as an historical review of the facts.

I disagree with Mr Hope Robbins’ opinion of witchcraft itself; but his contribution to the history of this subject is of prime importance.

The origin of torture and execution in the name of religion is the certainty that your religion is true, and therefore any other religion must be false. This being so, you must regard people who profess a different religion from your own as heretics, and as inevitably damned (as Saint Augustine did). It is your religious duty to persecute them; and because their crime is against God, no cruelty is too great to use towards them. Indeed, anyone who urges mercy towards heretics is suspect himself. The evidence of history shows overwhelmingly that witches were persecuted, not because they had done harm, but because their crime was heresy. Hence the heavy involvement, from the beginning, of the Church in witchcraft trials.

The extirpation of witchcraft was a religious duty. So we read of a witch being flogged to the sound of bells ringing the Angelus; of the torture chamber being censed with Church incense, and the instruments of torture blessed, before the proceedings commenced. We find documents, recording questions put to a woman under torture, which are headed with the letters “A.M.D.G.”, Ad majorem Dei gloriam, “To the greater glory of God”.

Nor were the Protestants any less cruel and fanatical than the Catholics. In fact, some of the most abominable stories come from the Protestant countries, particularly Scotland. The laws of Scotland with regard to witchcraft were different from those of England. Under Scottish law, torture was legal; under English law, after the Reformation, it was not.

Consequently, we may read such stories as that recorded of the trial of Alison Balfour, in Scotland in 1596. A confession of witchcraft was extorted from this woman by means of the ‘boots’, the ‘claspie-claws’, and the ‘pilnie-winks’. These were instruments of torture for causing agony to the legs, the arms, and the fingers, respectively; and could be applied with such violence that the blood spurted from the limbs.

Before Alison Balfour confessed what was required of her, she was put in the claspie-claws and kept so for forty-eight hours. Not content with this, the pious and God-fearing agents of the Kirk put her husband into heavy irons, and tortured her son with the boots; and as a final touch they took her daughter, a little girl of 7, and screwed the child’s fingers into the pilnie-winks, in the mother’s presence. At this juncture, Alison Balfour confessed; and upon the strength of this confession she was subsequently executed.

No mercy was shown, by either Protestant or Catholic, to children, if they were involved in witchcraft. That godly Puritan, Cotton Mather, in his account of the witchcraft trial at Mohra, in Sweden, in 1669, tells us with the utmost complacency how, after a good deal of praying, preaching and psalm-singing, “Fifteen children which likewise confessed that they were engaged in this witchery, died as the rest”; that is, by burning at the stake.

At other times, children of witch families were sentenced to be flogged while their relatives burned. The witch-hunter Nicholas Remy recorded this fact with regret; he felt that the children should have been burned as well.

The sentences of death in Scotland were sometimes carried out in a particularly horrible manner, and a relic of this survives today. It is the Witches’ Stone, near Forres, in Moray, Scotland. Beside the stone is an inscription, which says: “From Clust Hill witches were rolled in stout barrels through which knives were driven. When the barrels stopped they were burned with their mangled contents. This stone marks the site of one such burning”.

That this method of execution was carried out elsewhere in Scotland also, is attested by two Scottish writers, J. Mitchell and John Dickie, who published their book The Philosophy of Witchcraft in Paisley, Scotland, in 1839. They tell us:

There is a hill in Perthshire which bears the name of the Witches’ Crag to this day, and tradition still tells how it acquired the appellation. An old woman, who had been found guilty of Witchcraft, was taken to the top of it, and there put into a barrel, the sides and ends of which were stuck full of sharp-pointed nails. The barrel was then fitted up tightly, and suffered to roll down the steep declivity amid the rejoicings of the infuriated demons who had gathered together to witness the poor old woman’s tortures!! Where the barrel rested a bonfire was kindled, and it, and all that it contained, were consumed to ashes.

By “infuriated demons”, the authors mean, not evil spirits, but the witch-hunters and those who supported them, who had gathered together to enjoy the fun. Indeed, though they regarded themselves as acting from the highest and most religious motives, it seems that it was quite usual for the magistrates of a Scottish town to hold a public dinner after a witch-burning, as a form of celebration. There is a record of this being done at Paisley, in 1697, after seven people had been burned there as witches, in the presence of a vast crowd that had gathered to witness the scene.

It was on the Continent of Europe, however, and particularly in Germany, that the horrors of torture and cruelty raged most fiercely. Indeed, torture seems sometimes to have been indulged in for its own sake, even when the person had already confessed. The justification for this was, that a confession could not be fully true unless it was made under torture.

There were several degrees of torture practised in Germany in the seventeenth century, the blackest period of the whole history of witchcraft persecution. The first degree was called preparatory torture. It began with taking the prisoner to the torture chamber, and showing her the instruments, explaining in detail the particular agonies that each could inflict. Then the prisoner was stripped and made ready. Women prisoners were supposed to be stripped by respectable matrons; but in practice they were roughly handled and sometimes raped by the torturer’s assistants.

Then some preliminary taste of torture was inflicted on them, such as whipping, or an application of the thumb-screws. This preparatory examination was not officially reckoned as torture; so those who confessed anything under it were stated in the court records to have confessed voluntarily, without torture.

If, however, the prisoner did not confess, the jailers proceeded to the final torture. This was not supposed to be repeated more than three times; but again in practice there were no safeguards for the prisoner, and the tortures could be varied at will by the sadistic ingenuity of witch-judges. One of the worst of these was Judge Heinrich von Schultheis, who is recorded to have cut open a woman’s feet and poured boiling oil into the wounds. He wrote a book of instructions on how to proceed in witch trials, which was printed with the approbation of the Prince-Archbishop of Mainz. In this frightful volume, Schultheis declares that torture is a work pleasing in God’s sight, because by means of it witches are brought to confession. It is therefore good, both for the torturer and the one who is tortured.

A portrait of this monster has survived to us. It shows a handsomely-dressed gentleman, plump and well-groomed, with the wide lace-trimmed collar and neat beard and moustache that were worn at that period. Only the closely-set eyes betray the gloating cruelty of the sadistic killer; but this they do so completely that one cannot look at the face without a shudder. It may well be that his successors realised what Schultheis was; because only one copy of his book is known to exist, and that is in Cornell University Library. A book seldom disappears as completely as that, unless copies of it have been deliberately destroyed.

The final torture, therefore, had innumerable means of inflicting agony upon the human flesh—the thumb-screws, the rack, the rawhide whip, the iron chair (which was heated while the prisoner was held fastened in it), spiked metal chains which were tightened around the forehead, and so on. But the favourite method was that known as the strappado, from the Latin strappare, to pull. This was a means of dislocating the prisoner’s limbs, especially the shoulders. The victim’s hands were tied behind his back, and fastened to a rope with a pulley. Then, with a sudden pull, he was hoisted into the air. While he hung thus, heavy weights were tied to his feet to increase the pain.

While the prisoner was thus hanging, they were interrogated with questions, and the results written down as a ‘confession’. If they subsequently tried to deny or retract anything, they were tortured again. Sometimes they were tortured again, in any case, with particular severity, in order to force them to name ‘accomplices’. Names were suggested to them, of persons the authorities wished to implicate. By this means, more and more people could be drawn into the net of the witch-hunters.

For this purpose, a particularly agonising torture, known as squassation, was often employed. It was a further development of the strappado. The victim was hoisted in the same way, and kept hanging, with weights attached to the feet; but his body was then suddenly and violently dropped, nearly but not quite to the ground. The effect of this was to dislocate every joint of the body. Under this form of torture, prisoners sometimes collapsed and died. It was then given out that “The Devil had strangled them, to stop them revealing too much”, or some such story. They were regarded as guilty, and their bodies burned.

The worst period at Bamberg was under the rule of Prince-Bishop Gottfried Johann Georg II Fuchs von Dornheim, who came to be known as the Witch-Bishop. His reign lasted from 1623 to 1633, and in it he burned at least 600 people as witches. His cousin, the Prince-Bishop of Wurzberg, burned 900 alleged witches during his reign; but Bamberg became the more notorious, as being the very home of torture of the most atrocious kind.

Of particular interest is the Hexenhaus, or special prison for witches, that was built at Bamberg in 1627 by order of the Witch-Bishop. The building no longer exists, having been destroyed when witch-hunting went out of fashion and the Bishop’s successors became ashamed of it. In its day, however, it was considered a very handsome edifice, and a plan and picture of it remain. Besides two chapels and a torture-chamber, it had accommodation for the imprisonment, in separate cells, of twenty-six witches—two covens. On the front of the Hexenhaus were two stone tablets, bearing versions in Latin and German of a significant text from I Kings, Chap. IX, vs. 7, 8, and 9: “This house . . . shall be ... a byword. Everyone that passeth by it shall be astonished, and shall hiss, and they shall say, Why hath the Lord done this unto this land, and to this house? And they shall answer, Because they forsook the Lord their God . . . and have taken hold upon other gods, and have worshipped them, and served them; therefore hath the Lord brought upon them all this evil.”

This seems clearly to indicate that the witches were accused of having their own gods, instead of the Christian God.

Eventually, the reign of terror in Bamberg grew so scandalous that the Emperor himself took firm action to stop it. He was urged there-to by his Jesuit confessor, Father Lamormaini; a fact that should be recorded, to show that not all Christian priests approved of the proceedings against witches. Another Jesuit who spoke out against the torture of witches, with the utmost bravery, was Father Friedrich Von Spee, whose book Cautio Criminalis was published in Rinteln in 1631. He was imprisoned and disgraced for his boldness, and was probably lucky to escape execution.

From the worst of these manifestations of cruelty, England was mercifully free; mainly because English law is fundamentally different from Continental law, in that here the onus is on the prosecution to prove guilt, rather than on the prisoner to prove innocence, and that torture was not officially permitted. Such torture as did take place in England was unofficial and outside the law. It was administered by such rogues as Matthew Hopkins the notorious Witch-Finder General (See HOPKINS, MATTHEW), who found means to torment prisoners while still keeping within the letter of the law.

However, an influential Puritan divine, William Perkins, wrote in approval of subjecting witches to torture, in his Discourse of Witchcraft, published in Cambridge in 1608. Perkins says of torture that it might “no doubt lawfully and with good conscience be used, howbeit not in every case, but only upon strong and great presumptions going before, and when the party is obstinate”.

Sometimes such pious sentiments were unofficially acted upon. In 1603, at Catton in Suffolk, a mob got together to torture an 80-year-old woman Agnes Fenn, who was accused of witchcraft. She was punched with the handles of daggers, tossed up into the air, and terrorised by having a flash of gunpowder exploded in her face. Then someone prepared a rough instrument of torture almost worthy of Bamberg.

This consisted of a stool, through which sharp daggers and knives had been stuck, with the points protruding upwards. Then, says a contemporary account, “they often times struck her down upon the same stool whereby she was sore pricked and grievously hurt”.

TREES AND WITCHCRAFT

The late Elliott O’Donnell, author of so many volumes of ghost stories, also wrote a fascinating book called Strange Cults and Secret Societies of Modern London (Philip Allan, London, 1934). In this book, O’Donnell gives some very curious particulars of what he calls the tree cult. He relates how certain people, usually with something of the Celt in their ancestry, find a peculiar kinship with trees, and have some remarkable beliefs concerning them.

This tree cult is still in existence, and has a good deal in common with the Craft of the Wise. (It is not called ‘the tree cult’ by those who follow it; but it is convenient to follow O’Donnell’s example in naming it thus.)

Beliefs concerning trees, their magical properties and the spirits that are thought to indwell them, are so old and so widespread that it is impossible to do more here than give a glimpse into tree lore and its connections with witchcraft.

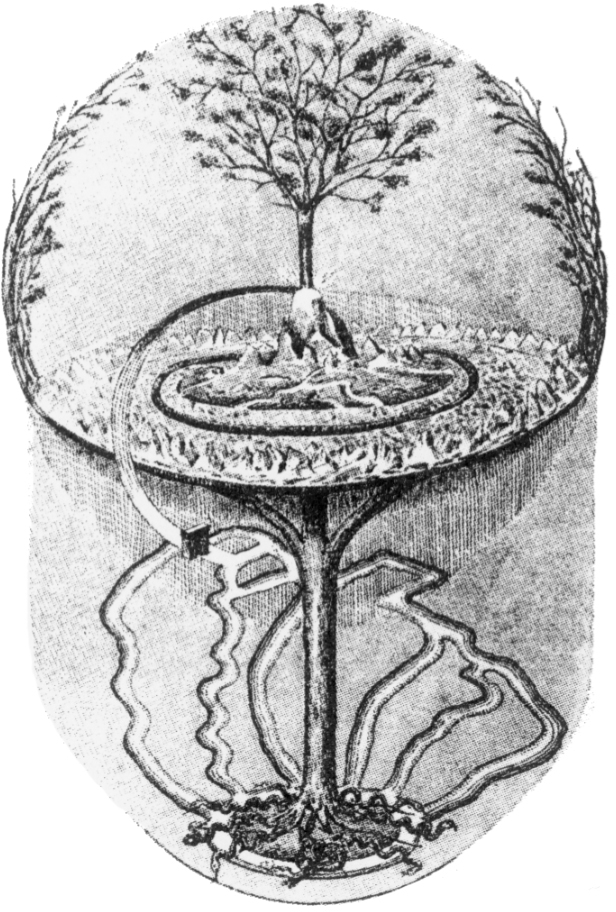

TREES AND WITCHCRAFT. The World Tree, Yggdrasill.

Trees not only have distinct personalities of their own, for those who are sensitive to such things; but many trees are the abodes of spirits, which may be friendly towards humans, or sometimes very much otherwise. Elliott O’Donnell had a curious word, ‘stichimonious’, to describe such spirit-haunted trees, which I have not seen elsewhere than in his works. He found so many stories of an uncanny or ghostly nature connected with trees that he later wrote a volume of such tales, entitled Trees of Ghostly Dread (Riders, London, 1958).

A haunted wood in Sussex, particularly connected with the ghost of a witch, is Tuck’s Wood near Buxted. The story behind this haunting is that, many years ago, a beautiful young girl called Nan Tuck somehow acquired the reputation of being a witch. One day an angry mob set about her and threatened to ‘swim’ her in the pond at Tickerage Mill. She fled, with the mob in pursuit, and made for Buxted Church to ask for sanctuary. She managed to reach the church, and tried to grasp the ‘sanctuary ring’ (the big ring of iron on many old-fashioned church doors). But the parson pushed her away, quoting the text about “not suffering a witch”; and presumably she was abandoned to the mob.

She subsequently hanged herself from a tree in Tuck’s Wood; and ever afterwards her ghost has haunted the wood and its neighbourhood. Her burial place is marked by an old grave slab outside the churchyard wall, near the lych gate.

It is not so inexplicable that there are many stories of ghostly phenomena connected with woods and with trees in general, when one realises that so old and powerful a living thing as a tree must have a strong aura, or field of force, surrounding it. Some sensitive people can see the auras of trees, as a faint silvery light against the sky. By leaning their back against a tree, they can attune themselves to its vitality, drawn deep from the earth and nourished by sunshine and rain. Many trees have a healing influence upon humans, when their life-force is contacted in this way.

The world’s oldest living things are trees—the ancient redwoods of California, estimated to be about 4,000 years old, and still producing buds and leaves. One of the world’s greatest pieces of music, Handel’s “Largo,” is a melody in praise of the beauty of a tree. There is far more in trees than merely wood and leaves.

A conspicuous tree has often been used as a trysting-place for many purposes, including those of the Old Religion. Solitary thorn trees, with their strange gnarled shapes, somehow suggest witchcraft and the Kingdom of Faerie; and few more so than the fantastic tree known as as the Witch of Hethel.

This very old thorn tree stands in the village of Hethel, south-west of Norwich, in Norfolk. How old it is, no one knows. A previous owner of the land, the first Sir Thomas Beavor, was said to have had a deed, dated early in the thirteenth century, which referred to the tree as “the old thorn”. Another scrap of tradition states that the tree was a meeting place for discontented peasants, when they staged a revolt in the troubled reign of King John (1199–1216).

Today, the trunk of the thorn is cloven, and its twisting branches have spread to become like a miniature wood in themselves. In several places, they are supported by props. Yet in spite of its amazing age, the Witch of Hethel still manages to produce a few bunches of sweet-smelling blossom each May. Happily, this historic tree is today cared for by the Norfolk Naturalists’ Trust.

But why is it called the Witch of Hethel? No one seems exactly to know. There is one significant pointer; the tree stands near to the village church, and although the latter is old, the thorn is thought to be older. We know that early churches were often built upon pagan sacred sites; so this church may have been deliberately built near a sacred tree. The Witch of Hethel may once have been the Goddess of Hethel, under the form of her sacred tree.

That hawthorn was once a sacred tree is shown by the fact that it is considered unlucky to bring its blossoms indoors. The only time when it was lawful to break the branches of the White Goddess’s tree was on May Eve, when they were used in the May Day celebrations. There are many folk tales of people who have suffered injury or misfortune, through cutting down or uprooting some venerable old thorn tree.

The oak, the ash and the thorn are the Fairy Triad; and where they grow together, you may expect fairies to haunt. There is a popular rhyme in the New Forest:

Turn your cloaks,

For fairy folks

Are in old oaks.

Turning your cloak inside out, and wearing it like that, was a remedy for being ‘pixy-led’, or made to lose one’s way by fairy glamour.

The oak is the old British tree of magic, reverenced by the Druids; one of the mightiest and longest-lived of trees, and yet lying potentially within the smallness of the acorn. This is the probable origin of the old Sussex belief that to carry an acorn in one’s purse or pocket will preserve health and vitality and keep one youthful.

Also, the acorn in its cup is phallic in shape, and hence an emblem of life and luck. For this reason, the heads of gateposts at the entrance to a house were in olden times often carved in the shape of an acorn.

This is the reason, too, why old-fashioned roller blinds at windows often have a carved wooden acorn at the end of their cords. The acorn hung at the window originally to bring good luck, and keep away evil influences. Its real meaning tended gradually to be forgotten; but the custom of decorating window blinds with an acorn remained.

It has been suggested that the old nonsense-words, ‘Hob a derry down-O’, which sometimes occur in folk-songs, are actually the worndown remains of a Celtic phrase, meaning ‘Dance around the oak-tree’. Derw is the old British word for oak; and it seems fairly sure that Derwydd, meaning ‘oak-seer’, is the origin of ‘Druid’. Present-day witches sometimes dance around an oak or a thorn-tree and pour a libation of red wine at its root. The tree is an emblem of the power of life and fertility, which they worship by this act.

Fragments of traditional lore about trees often bear witness to their ancient importance in pagan religion. For instance, there is a curious passage in John Evelyn’s book, Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest Trees (London, 1664). Writing of a certain very old and venerable oak-tree in Staffordshire, he tell us: “Upon oath of a bastard’s being begotten within reach of the shade of its boughs (which I can assure you at the rising and declining of the sun is very ample), the offence was not obnoxious to the censure of either ecclesiastical or civil magistrate.”

This seems certainly to hark back to the fertility rites of olden times, beneath the sacred oak. The same old custom lies concealed in a certain Sussex place-name, Wappingthorn Wood, just north of Steyning. ‘Wap’ or ‘wape’ is an old word meaning to have sexual intercourse, in this case beneath the sacred thorn tree.

The elder is a tree of rather sinister repute, and much associated with witchcraft. No careful countryman of olden days would burn logs of elder in his fireplace, because to do so would bring the Devil into the house. The berries of the elder make potent wine, and its strongly-scented white flowers are valued by the herbalist, to make elder-flower and peppermint mixture, a remedy for colds and chills. Yet there is something disturbing about the heavy perfume of elder flowers in the warm air of summer. Arthur Machen described it in a telling phrase, as “a vapour of incense and corruption”. Some regard it as noxious, while others believe it to be an aphrodisiac.

The elder tree is notoriously a dwelling place of spirits; so much so that an old belief says you should never cut or break a piece from an elder tree, without asking leave of any unseen presences. An elder tree that grows in an old churchyard is particularly potent for magical purposes. For instance, it can be used to charm warts, if you cut a small stick of green wood from it in the waning moon, rub the warts with the elder stick and then bury it somewhere where it will be undisturbed and rot away. As the stick decays, so the warts will disappear.

Some people believed the elder to be a protection against witchcraft; perhaps because it was thought to be the tree of which the Cross was made, and also the tree on which Judas hanged himself. Others regarded solitary elder bushes with suspicion, especially if they encountered one in the twilight where they could not remember seeing a bush before. It might be a witch in disguise, changed by magical glamour into the appearance of an elder tree. Some old stories said that witches could do this. There are so many legends about the elder tree that its association with magic and witchcraft is almost certainly pre-Christian.

A continuing cult of magical beliefs connected with trees is shown by a curious incident that happened in Sussex in 1966. In March of that year the Brighton Evening Argus reported that a curse had been publicly laid upon whoever cut down an ancient elm tree near Steyning, Sussex. The tree was threatened with destruction to make way for housing development; and a notice had been found pinned to it, which read:

Hear ye, hear ye, that any fool,

Who upon this tree shall lay a tool,

Will have upon him a curse laid,

Until for that sin he has paid.

The notice was adorned with magical symbols. The police investigated the matter; but so far as I know the author of the mysterious threat was never discovered.

The expression ‘Touch wood’ is a relic of the ancient worship of trees. (I once had a man say to me, in all seriousness, “I don’t believe in superstition; and, touch wood, I never shall!”) The concepts of the World Tree or the Tree of Life occur again and again in pagan mythology and symbolism. Our Christmas tree, with its bright baubles and the star on the top, is a miniature version of the World Tree of our pagan ancestors, with its roots deep in earth, the sun, moon and stars hung on its spreading branches, and the Pole Star on its topmost point. Sometimes the star is replaced by a fairy doll, who represents the goddess of Nature ruling over the world.

A sign that a tree is the home of uncanny influences, is the presence upon it of the peculiar growth that country people call witches’ brooms. This appearance is actually caused by a kind of fungus, which has the effect of stimulating certain branches of the tree into unnaturally thick growth, dense and bushy like a broom. The broom-like cluster of branches also tends to come into leaf before the rest of the tree. A tree that had the sign of the witches’ broom upon it was certain to have something strange and magical about it, in old country lore.