oNE SPRING AFTERNOON IN 1994, DONATELLA STOOD AT THE center of a huge loftlike photography set in downtown Manhattan. Next to her was Richard Avedon, the legendary fashion photographer, hunched behind a large camera under enormous umbrella lights. An array of assistants stood behind the pair, gaping at the spectacle unfolding before them. The subject of their attention was a male model, buck-naked and gyrating wildly to music blasting over the sound system. The man, who had an Atlas-like physique and curly dark hair, was in fact a stripper whom Donatella had spotted in a dance club in Miami. She thought he would be perfect for one of Gianni’s ad campaigns and had flown him to New York.

As Donatella stared, the stripper turned the show up a notch and began sliding a silk Versace scarf between his legs. Next to her, Avedon, his face a mask of concentrated tension, clicked away. “Oh, my God!” Donatella said, laughing at the scene. “Gianni is going to love this!” The final photo showed the man with his head lolling back, an orgasmic look on his face.

By then, even as Gianni shirked much of the cosmopolitan, sexually charged lifestyle his clothes had come to represent, his sister was fully embracing the Versace mystique—and nowhere more so than on the Versace ad shoots. Indeed, as Gianni rose, so did Donatella. As the family business became an international success, she would be the lead player in the grand opera that was the Versace brand in the 1990s. By then, Donatella’s natural theatricality served the company well, if expensively. Gianni had begun entrusting Donatella with the advertising campaigns in the 1980s, and a decade later, they were productions worthy of Hollywood films. Under Donatella’s direction, Versace shoots had become notorious for their extravagance, their brazen sexiness, and their illicit fun.

From the birth of his house, Gianni had always demanded the most extravagant ads he could afford. When he launched his first ad campaign in 1978, he spent his entire budget to hire Richard Avedon, who since the 1940s had been the world’s premier fashion photographer. Working with the top fashion magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, Avedon helped develop an image of women that reflected the times—freer and more flamboyant—with pictures full of drama and spontaneity. In 1955, for example, he shot Dovima at the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris. Avedon positioned the ephemeral American model in front of two elephants. It became one of the most famous fashion photographs of all time.

Avedon’s collaboration with Versace would be nearly as iconic as his innovative early work. His theatrical style made Gianni’s clothes come alive. But after initially working with Avedon in one campaign, Gianni had to deputize Donatella to deal with the famous photographer, because Avedon didn’t want the pressure of having the star designer hovering over him. Donatella could channel Gianni’s wishes with a lighter touch.

“Gianni came once, but he made such havoc,” Donatella said. “It was hard for him to pull back from his clothes and see how a photographer interprets them. He used to say, ‘No, you have to do it this way or that way.’ Finally, Avedon said, ‘You can’t come anymore. Send your sister.’”1

Over the next twenty years, Avedon, a legendary perfectionist, staged elaborate shots of the Versace female models—for example, falling through the air or riding on the backs of naked men. For one shot showcasing Gianni’s 1996 home furnishings line, Avedon had a dozen massive mattresses made, covered them in bright Versace prints, piled them high, and slid the models in between them, to create a huge princess-and-the-pea effect, with Naomi Campbell and Kristen McMenamy perched on top. In another shoot, he hired a choreographer from Twyla Tharp’s dance troupe to give a jolt of drama and theater to the girls’ movements.

The shoots, with Donatella orchestrating, involved dozens of people and lasted up to ten days. Avedon often photographed a large group of supermodels at a time, sprinkling in a couple of hunky men for the full sexual charge. The whole collection for the upcoming season hung on a battalion of clothing racks alongside long tables overflowing with shoes, bags, and jewelry. Some seasons, it took three assistants just to lay out the clothes. Avedon’s own Manhattan studio was far too small to accommodate the shoots, so he sometimes rented Silvercup Studios, a sound set in Queens nearly the size of half a city block, where The Sopranos was later shot.

Donatella spent days assembling the outfits with several assistants, while seamstresses from the Manhattan Versace shop fitted the clothes. Each day of the shoot, hair and makeup artists spent at least six hours dolling up the girls in a mirror image of what was, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Donatella’s own look: strong eye makeup, ultratanned skin, and only a hint of beige lipstick, simulating the style of rich 1960s movie stars. Makeup assistants spent hours covering the models with full-body makeup, a gooey blend of several shades, before fixing it with a powder to keep it from rubbing off on the clothes. They put three or four pairs of false eyelashes on each woman. Donatella herself wore up to five pairs; to her delight, a makeup artist once found 1960s-era lashes made of real mink for her.

“She was a maximalist,” said François Nars, a top makeup artist who worked on the Avedon shoots. “And the girls ended up looking like her. The more the better.”2

During the long preparations, Donatella would float off the set to go shopping in New York, often coming back with gifts for the models and her assistants. One season she discovered a new skin cream made with animal placenta and brought back a jar for each one. Other times, she arrived with pricier baubles for herself.

“If she was thinking of buying a diamond and emerald ring, she would come in and show it to everyone,” recalled Norma Stevens, Avedon’s business partner. “She was wild, with that blond hair and the tight clothes and her figure.”3

Donatella made sure the opulence and theater of the sets spilled over backstage. Gianni was using the same supermodels season after season, and the atmosphere was like a family reunion. Waiters refreshed buffet tables of food all day. (Once, on a Los Angeles beach set with another photographer, Donatella hired famed chef Nobu Matsuhisa to bring sushi for everyone.) She booked masseuses for the models and blasted music to keep the energy high. Sometimes the female models’ boyfriends stopped by; one year, Johnny Depp hung out to watch his girlfriend Kate Moss be photographed. With all the high-drama clothes, gorgeous women and men, and creative frisson, the set was red hot.

After each carefully arranged shot, an assistant would hand Avedon an oversized photo, and he and Donatella would huddle over it. The photographer would mark up the shot with a black marker, pointing out where the line of the models’ elbows or the flow of the dress broke the harmony. “My role was to tell him which outfits we wanted him to shoot and how,” Donatella said. “He showed me these huge Polaroids and I would say yes or no. It was scary.”4

Avedon was so exacting that he approved only one or two shots each day. (Today, with digital photos and computer retouching, photographers take scores of images daily, and shoots last no more than three days.) The shoots cost a fortune. “We had a so-called budget,” Donatella said. “But Avedon used to work with the top models, the best set designers, the best hairdressers—all of whom cost a fortune. We just tallied it all up afterward.”5

As the Versace mystique mounted, Donatella was leading a life of such operatic excess that one imagined she had hired an art director to conjure it all up. Her physical appearance morphed into a gilded Jan-from-the-Muppets look. She was rarely the most beautiful woman in the room—much to her chagrin—but she acquired a sort of mysterious charisma that made her the constant center of attention. Her high-voltage, Vegas-meets—St. Tropez style featured skintight, side-zipped tops in Crayola colors, neon orange nail varnish, chartreuse bikinis, and platform shoes with five-inch heels. She wore lots of sleeveless shift dresses in a variety of colors—but never red, which was Valentino’s color—that showed off arms that were as thin as wands. She chucked her wardrobe at the end of each season and bought all new clothes.

In interviews with journalists, Donatella maintained her camp goddess persona, claiming to wear lace and silk lingerie around the house and diamonds to the gym. (When she answered questions, she blithely mangled the English language, often resorting to her favorite words, “modern” and “fabulous.”) She knew which was her better side and insisted on being photographed standing up, lest she look thick in the waist. “I don’t mind not being tall,” she once told a Vanity Fair journalist defiantly. “I think tall.”6

While Gianni took himself seriously, Donatella had a sense of irony and wry humor about herself and the grandiose life she and her siblings had created. Privately, she was utterly candid, frank, and hugely fun, possessing a comedian’s sense of timing. “When I die, I want to be buried in a glass coffin like Snow White,” she often quipped. In the atelier, her vampy image belied a more homey character. She traded diet tips with her female assistants and invited favored employees to eat lunch with her in the family kitchen. She listened to the personal travails of the people working with her, inquiring after their pets and babies with genuine interest. If the team had to work late, she ordered pizza for everyone and let the mothers on her staff bring their kids to do their homework in the atelier. She was unstintingly generous with loyal assistants. Once, she sent a stylist a bouquet of flowers the size of a coffee table—interlaced with chocolates and bananas, his diet during the long ad shoots they did together.

But as her brother grew more successful and celebrated, she gradually became the emperor’s wife. For instance, at the Ritz in Paris, Gianni was enormously popular because he remembered hotel staff members’ names and stopped to chat when he came down to raid the shop for newspapers and magazines. By contrast, Donatella breezed past when she came and went, wearing dark sunglasses and trailed by a couple of bodyguards. When she stayed at the Ritz, she often flew in her own florist from Milan, deeming the hotel’s florist inadequate.

She outdid Gianni in her grandiosity. When the siblings stayed at the Ritz, Gianni opted for a normal suite, not one of the “name” accommodations, such as the Imperial Suite. Once, however, he asked to see one of the top suites. “Perhaps you would like to stay here instead?” the manager asked Gianni, after showing him the opulent rooms and telling him the price. “No, it’s too expensive,” he decreed. “Give it to my sister. She likes grand things.”

Donatella spent money as if she were a spoiled teenager. She constantly overdrew her salary and the allowances Santo gave her, but her brothers always covered her debts.

“I’m so depressed today,” she sometimes told an assistant, flopping in a chair. To cheer herself up, she went down to Cartier on Via Montenapoleone—her favorite jeweler, along with Harry Winston in New York—to pick up a new bracelet or ring. She traveled by Concorde or private jet and stayed in the best suites at the Dorchester Hotel in London, the Waldorf Towers in New York, and the bungalows at the Beverly Hills Hotel. She stayed so often at the Dorchester that they started to prep the room with a floral perfume that she loved. Once, she rented an enormous villa in St. Tropez that belonged to French rock star Johnny Hallyday. She loved the house—but not his furnishings, which ran to Native American taste. “Johnny, I love you, but I’m bringing my own furniture,” she told the celebrity.7

In Milan, her apartment was a pleasure palace. The twenty-one-room home had two kitchens, always fully stocked so that she could throw impromptu dinner parties, and several dressing rooms, with vast closets. She had two stereo systems installed, on two different floors, with different music playing to suit her moods. Her bathroom—dubbed the eighth wonder of the world by one friend—contained python-covered chairs, intricate tile work depicting massive Magritte-like pink and red lips, and wide custom-made shelves holding a vast array of creams, potions, and bath salts. (Whenever she liked a product, she bought three bottles of it.) Every evening, she took a soak in a magnificent marble tub.8

With his enormous workload, Gianni typically went to bed early, leaving it to Donatella to create the high-life image that the Versace brand projected. Everyone in fashion and show business knew that, after Gianni went to bed, Donatella turned up the volume—supermodels, A-list celebrities, and über-hip photographers, all in a swirl of coke, champagne, and loud music. Donatella became Gianni’s roving evangelist, spreading the gospel of Versace. With her partying, ad shoots, and celebrity friends, Donatella absorbed what was hot and new and, back in Milan, transmitted that to Gianni.

“I moved in this world that didn’t really exist in Milan,” said Donatella. “I was great friends with the models, the photographers. I hung out with rock stars and went to places he didn’t go that often. I came back and gave him information he wouldn’t have had if it weren’t for my lifestyle. I would tell him how people are dressing or that a certain trend was over or that young people were looking for this. I was his eyes.”9

During the week before a show, Gianni put enormous pressure on Donatella. She had to be at his side constantly. Yet Gianni did not make it easy for her. Most designers decide what looks they want to show and then have the samples made up, but Gianni did the opposite. He had a huge number of samples made, and then spent more than a week painstakingly mixing and matching until he distilled the looks he wanted. His color palette was far more vast than that of most designers, so he had skirts, jackets, leggings, and dresses made up in a rainbow of colors. He had as many as five hundred pairs of shoes made, each in five sizes. Between the clothes and the accessories, there could be up to two thousand pieces for Gianni to choose from—and seek Donatella’s advice about.

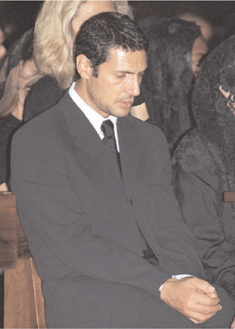

Even as Gianni’s boyfriend, Antonio D’Amico, grieved at the funeral in Milan, his relationship with Donatella was disintegrating.

This little black dress not only shot Elizabeth Hurley to fame, but exemplified Gianni’s newfound love affair with the stars.

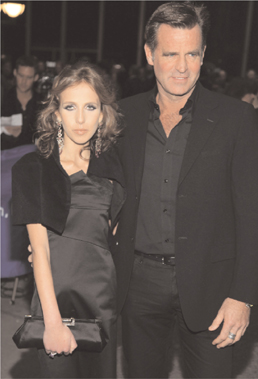

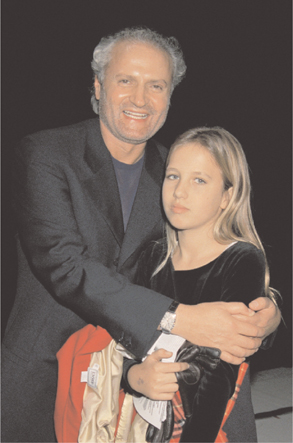

The future of Gianni’s house now sits on the shoulders of Allegra (shown with her father, Paul, who is separated from Donatella).

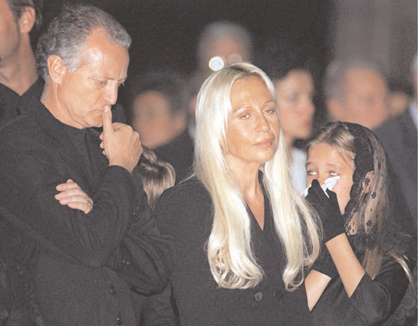

Together Santo and Donatella, with Allegra at her side, grieve their brother in Milan’s magnificent Duomo. But the siblings would soon be at war over Gianni’s legacy.

For Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace represented a deadly obsession.

The fierce rivalry between Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace lit up the fashion world for two decades.

Gianni and Donatella put on a united front at a red-carpet event in London in 1995. But behind the scenes, tensions between the siblings were quickly rising.

Gianni with his niece Allegra at a ballet in Paris just months before his death. In one rash decision, he bestowed an enormous burden on his beloved principessa.

Elton John, comforted by his boyfriend, David Furnish, grieves Gianni’s death with Princess Diana. It would be one of the princess’s last public appearances before her death just a month later.

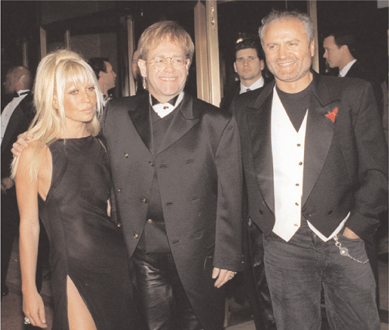

Donatella, Elton John, and Gianni arrive at a fashion awards gala in New York. Soon after, Elton would inform Gianni of Donatella’s heavy drug use.

Donatella at a men’s fashion show in 2008. Gianni’s kid sister has prevailed over her drug habit and the near collapse of her brother’s house only to face the worst recession to hit the fashion industry in decades.

Casa Casuarina, Gianni’s fabulous Miami mansion, became a symbol of South Beach’s 1990s decadence—and an exclamation point on Donatella’s life of excess. But it also made Gianni the target of a killer.

Gianni spent millions renovating Casa Casuarina, sparking tensions with his brother, Santo. Gianni’s extravagance would lead to a fight between the brothers that changed the fate of the house of Versace.

Because Gianni’s shows were so complicated to stage, he held full dress rehearsals—after which he might reshuffle the models and even demand a new garment be made. The shows themselves were very long, lasting up to fifty minutes and featuring more than one hundred outfits. (Today, Versace shows last less than twenty minutes, with a third of the looks.)

Donatella was a living spark for Gianni’s last-minute creativity. For instance, in 1990, Gianni made a dress that was a virtuoso display of his stagecraft and dressmaking skills. From the front, it was a prim black jersey dress, with a high neckline, long sleeves, and ankle-length skirt. But in the back it plunged to the base of the spine, while a slit ran all the way up the leg. The dress was held together precariously at the hip. Originally, Gianni had decided to show the dress with embroidered stockings and to have a black model wear it. But when Donatella saw it on the model, she understood that the tights and the woman drained the dress of its high drama. “Gianni, those stockings are going to kill it,” she told him. “That dress will be nothing unless you show it without stockings.”

Gianni refused. So in the backstage chaos before the show, Donatella instructed one of the dressers to put the dress on Christy Turlington—without stockings. “He’s going to kill me when he sees this,” she whispered to an assistant. As Christy made her way down the runway, the audience at first saw a prim black dress. But when the model made her turn at the end, showing the vertiginous gown on her long, bare legs, lean back, and perfect bottom, a roar went up from the audience.

“When she walked back up the runway, you sat there holding your breath because you thought you were going to see her backside at any moment,” remembered Joan Kaner, fashion director of Neiman Marcus. “It was breathtaking.”10 Gianni was thrilled.

Later, in 1992, Gianni and Donatella were fitting Trudie Styler for the ornate dress she would wear for her wedding to Sting. Versace seamstresses had spent weeks embroidering the sleeves on the ensemble’s gold jacket. In the atelier, Donatella paced furiously, looking at the gown, while Gianni stood nearby, his brow furrowed.

“What do you think?” he asked her in Italian, as Styler stood by, struggling to understand what they were saying.

“It’s the sleeves,” she said. “They’re all wrong. They have to go.” Gianni looked at her, glanced back at the dress, grabbed a pair of scissors, and snipped off the sleeves, leaving them to plop to the floor. The two seamstresses who had done the intricate work stood aghast. Styler’s eyes widened in horror.

“Brava, Donatella! Brava!” Gianni told his sister, his eyes lighting up. “Now it’s perfect.” At Styler’s wedding a few weeks later, she made a grand entrance on horseback, the train of the dress spread behind her.11

The strain of working closely with Gianni was tough on Donatella, who sought refuge from her brother’s relentlessness in her long trips abroad. “He sucked her in,” recalled an assistant. “He never let her in peace. He was always saying, ‘Ask Donatella about this or that.’ But Donatella wasn’t as wholly devoted to work as Gianni was. She got up later. She had her hair appointments, her shopping, her children. So she escaped by traveling a lot.” She frequently kept people waiting and made her assistants work late into the evening because her schedule ran hours behind. Gianni, so punctual and demanding of his team, often seethed at his sister’s lax work habits.

Although Donatella inspired Gianni, she wasn’t one to summon ideas on her own. Her role, while priceless, was a sideline to Gianni’s talent. She was a catalyst or instigator, a brutally honest sounding board that pushed Gianni to distill his best work.

“The creative genius was Gianni,” one assistant said. “Donatella was someone of whom you asked an opinion, but not ideas. She never came in saying, ‘I’ve got this idea.’ Their roles were very separate. Gianni needed advice on things like, ‘Do we shorten it or lengthen it? Do we make it tighter or looser? Do we use more blue?’”

Donatella didn’t have nearly the stamina or tremendous focus that Gianni had. Her attention span was like the beam from a lighthouse, shining on problems in short, sharp bursts before waning. “Donatella had the ability to take Gianni’s designs to the extreme,” said another longtime assistant. “If Gianni was the cake, she was the one who could put the icing and the cherry on it. But without him, there was no cake.”

One day around 1994, Elton John told Gianni he needed to speak to him about something important. For some time, Elton had heard rumors about Donatella, but recently they had become embarrassing enough to push him to call his friend. “Listen, Gianni, people are laughing at Donatella in America,” he told him over the telephone. “She goes to all of these parties and she’s always running out of the room. When she comes back, everyone can see that she’s stoned.”12

Gianni was furious. Years earlier, Donatella had told him that she used cocaine, but he thought it was a youthful indulgence that had long ceased. In reality, Donatella had become a heavy user over the years. The first time she tried coke, she was unimpressed; she simply felt more awake. But during the 1980s, she became a hard partyer, running with an über-cool crowd of models, rock stars, celebrity hairdressers, and hot photographers. As a result, she found herself more and more often in clubs where people openly used drugs. At a party in New York, she was shocked to find people snorting cocaine on the dance floor.13

In a world of fragile, creative egos, many designers used cocaine to paper over their insecurities and cope with the relentless pressures of the fashion cycle. Some designers kept employees on their payroll because they had good drug connections. By the late 1980s, drugs had long since lost any scandalous sting backstage at fashion shows, with hairdressers and makeup artists especially avid users. Teenage fashion models, loath to drink alcohol because of the calories and seeking a boost to endure six weeks of dawn-to-midnight runway shows and rehearsals, snorted coke from “bullets” in the shape of lipstick holders stashed in their purses. Insiders knew that “Do I smell Chanel?” was code for “Is there any coke?”14

Initially, Donatella tried to confine her drug use to her long trips to the United States, far from the scrutiny of her two brothers. She used only cocaine and drank very little, with the exception of a flute of champagne. The photography shoots for Versace ads were a favorite escape for her. The ten-day events, with their high energy and sexed-up air, were heady fun, which Donatella upped with bumps of cocaine. She often drafted a friend or an assistant to join her, and they ducked into the nearest bathroom, the only private space on the sprawling sets.

“Donatella always had the best quality coke,” recalled a friend who did it with her on the sets. “Donatella would pull it out and I would say, ‘Oh, I really shouldn’t.’ She would just laugh. She used to do it almost every day, in the afternoon. It was like a cocktail.”

Donatella would flip her long hair back over her shoulder and bend over, using whatever utensil she could find to scoop the powder into her nose. Afterward, she pulled back, with a satisfied, catlike look on her face. “We used to use the caps of Bic pens or rolled-up dollar bills,” the friend recalled with a laugh. “We were like ghetto queens.”

Once, Donatella was so high that she didn’t even bother to turn up on the set. Normally, Gianni called her a dozen times a day when she was on a shoot. That particular day, as everyone looked for her, Gianni finally got her on the phone and asked, “How are the pictures?”

“Fabulous, Gianni,” she replied. “Just fabulous.”15

“I didn’t regret at all not showing up at the shoot,” she reflected years later. “I had so much fun. I had the best time of my life.”16

When Elton called Gianni to tell him that people were sniggering about Donatella’s drug use, Gianni, who had never touched drugs and barely drank, had no sympathy for his sister’s habits. In part, he was worried that Donatella would damage her health. Moreover, he was afraid that Donatella’s habit would cause problems for the company. He had indulged and spoiled his little sister their entire lives, but he couldn’t fathom her fondness for drugs. He was also angry that Donatella’s personal habits could make him—and his work—look bad.

“Gianni knew that, when you’re on top, you’re in everyone’s sights, and you can’t put a foot wrong,” said Antonio D’Amico. “The idea that people were speaking badly about the company [because of Donatella’s habit] hurt him.”17

Gianni knew, however, that his sister wouldn’t stop. Indeed, as he soon recognized, her drug use was interfering more and more often with her work in Milan. At Via Gesù, the seamstresses tittered when she ducked into their bathroom with an assistant, both giggling loudly before emerging with a glazed look on their faces. She didn’t even refrain during fashion week, when Gianni, already a bag of nerves before a show, counted on her help the most. “Where the hell is my sister?” Gianni would scream, sending his team scrambling to look for her.

“You can imagine how hard that was, given her problem,” said one assistant. “Every five minutes, she was running out, and we had to go find her.”

On one occasion, she went too far. A group of friends had just flown into Milan for the show, and Donatella was restless to party. She and her friends stayed up all night, bingeing on cocaine. The next day, she slept until the afternoon, rolling up to Via Gesù feeling and looking awful. Gianni and his team had been waiting impatiently for her since the first thing that morning. When he saw her, he exploded. “It doesn’t matter what you do, but you have to know how to do it and when to do it!” he screamed at her. Feeling guilty, she slunk away.18

As her drug habit deepened, Donatella became less predictable in the atelier, routinely turning up to work at noon. She kept associates waiting for hours, and her schedule ran late into the evening. Gianni demanded that his staff give him their all, and his sister’s wayward habits drove him to distraction. “Gianni used to call her in the morning, and you could hear that she was still in this haze, with this croaky voice,” Antonio said. “She wouldn’t get to work until late, and when she did, she was in pieces.”19