I. St Petersburg, Lucy and the Urals’ Natural Wealth

THOMAS WITLAM ATKINSON arrived in St Petersburg in the first half of 1846. He would have found Russia’s capital much as we know it today, with its great buildings and the needle spire of St Peter and Paul’s cathedral dominating the north side of the Neva. Across the river was the spire of the massive Admiralty from which begins the Nevsky Prospect, the city’s main street, dead straight for most of its 5-km length; next to the Admiralty, facing the river, was the long façade of the Winter Palace and the Hermitage.

He would have come up the Neva, passing the fashionable English Embankment, so called from the wealthy English merchants who had built their houses along it in the mid-eighteenth century. Peter the Great had recruited Europeans to develop his new capital and by 1846 the number of British had grown into a large colony, with not only its Embankment but the English Church, seating 500, and the English Club, not to mention an English Park, Palace, Shop, Bookseller, Subscription Library and even a boarding school for girls.1 As to the purpose of his visit, there is no evidence of any architectural project, and perhaps his objective from the start was to travel and sketch. At all events he had the luck at some stage to meet Admiral Peter Rikord (1776–1855) – spelt by Thomas in his subsequent book as ‘Rickhardt’ – who had been governor of Kamchatka, Russia’s remote peninsula, 1,200 km long, on the North Pacific coast, and was able to give the prospective traveller much information about the route east (as Thomas acknowledges on the very first page of his future book).2

But it may have been Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), the great Prussian scientist and explorer,3 internationally famous in his lifetime, who inspired Thomas’s travels in the Russian Empire. Humboldt had preceded Thomas to Russia, and as a celebrity who had originally studied mining and been a chief mining inspector, he had been invited by Tsar Nicholas I for a six-month summer expedition in 1829 at the Tsar’s expense to study mining and geology in the Urals. Thomas would have known of this eighteen years later, particularly because Humboldt gave him a letter (probably of introduction) to take to the Russian Admiral Lütke, co-founder member with Admiral Rikord of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society.4 It is strange that he did not record his thanks to either Humboldt or Lütke along with other grand names in his first book, although it seems an obvious inspiration.

Why did he, at the age of forty-seven, set out on these ambitious travels, which (he could not know) were to last for seven years? ‘My sole object’, he wrote on his return, ‘was to sketch the scenery of Siberia – scarcely at all known to Europeans.’ Ultimately he produced 560 sketches, and in the preface to his first book he highly praised the ‘moist colours’ (by which he means watercolours in tubes) of Winsor and Newton’s paints, invaluable in huge variations of temperature ranging from (he claims) 62ºC ‘on the sandy plains of Central Asia’ to –54°C in the Siberian winter when they were ‘frozen as solid as a mass of iron. With cake colours [i.e. the small blocks of colour in paintboxes] all my efforts would have been useless.’

When Thomas arrived, Nicholas I had been on the throne for twenty-one years. His reign had begun with the Decembrist conspiracy, an abortive rising by young aristocratic army officers which he reluctantly crushed with cannon fire and followed with the execution of five of the ringleaders, life imprisonment with hard labour in Siberia for thirty-one and 253 shorter sentences.5 Thereafter he ruled with severity and tight control – establishing the ‘Third Section’, a secret police force abolished only in 1880. Physically, Nicholas was ‘a perfect colossus, combining grace and beauty … his countenance severe, his eye like an eagle’s and his smile like the sun breaking through a thundercloud’.6 His reputation as an anglophile as well as his interest in art and architecture may have encouraged Thomas to write to him in August 1846 in appropriately deferential language (via the British chargé d’affaires, Andrew Buchanan,7 in the Ambassador’s absence). Thomas turned to the Emperor as he had learnt that the Russian authorities would give a passport only from one town to another, which would present a truly formidable obstacle to his hopes of extensive travel.

Buchanan evidently forwarded the letter on to Count Karl Nesselrode, Russia’s Baltic German Foreign Minister.8 Three days later9 Nesselrode wrote to Buchanan, saying that he had shown the Tsar the letter and ‘His Imperial Majesty has deigned to grant his agreement’ to Thomas’s request for ‘un voyage artistique aux Monts Oural et Altai’.

The same day Nesselrode’s office wrote to Vronchin, Minister of Finances, informing him both of the Emperor’s permission and Nesselrode’s order to the Urals’ extensive mining administration to help the prospective traveller. Vronchin conveyed the Emperor’s ‘gracious approval’ to the general director of the Corps of Mining Engineers, so that the latter could give the necessary orders and request the governors of the relevant gubernias (provinces) to be of service, and another four days later Nesselrode was informed that the heads of both the Urals and Altai mining operations had already been instructed to provide ‘all possible cooperation’.

A little over a month later an all-important document reached Thomas to which was attached a large red seal:

Palace Square, view from the arch of the army headquarters, St Petersburg

Beyond the great Palace Square lies the long façade of the Winter Palace, the eighteenth-century imperial palace, designed by the Italian architect Rastrelli. In the centre stands the Alexander Column, commemorating the reign of Alexander I. Colour lithograph after Louis Jules Arnout. Giclée print, c. 1840, by Lemercier, Paris.

LAISSEZ PASSER

By decree of His Majesty the Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich, Autocrat of All The Russias & etc., & etc., & etc.

The bearer of this [pass], a British citizen, the painter Atkinson with the supreme permission of the Emperor, is authorised to proceed to the Ural and Altai mountain ranges to produce views of local scenes. In consequence, the Town and Rural police departments of those provinces to which the painter Atkinson is heading, as well as those through which he may pass, are instructed to render him assistance where possible for his passage and the successful attainment of his journey’s aim.

This pass signed by me and stamped with my coat of arms in St. Petersburg September the 21st day of the year 1846.

(Signed) Perovsky10

(Signed) Director of the Executive Police Department: Rzhevskii (STAMP)

In the preface to Thomas’s first book he said: ‘Without his [i.e. the Emperor’s] passport I should have been stopped at every government, and insurmountable difficulties would have been thrown in my way. This slip of paper proved a talisman wherever presented in his dominions, and swept down every obstacle raised to bar my progress.’

Oddly, the English geologist with whom Thomas hoped to travel was scarcely referred to in all this high-level correspondence, and never by name. One must assume he was given a separate laissez passer. Charles Edward Austin (1819–1893) was twenty years younger than Thomas and far more of an engineer than a geologist as he had been described to the Tsar. He had started his career as a pupil of Brunel’s chief assistant on the Great Western Railway and worked on it till its completion in 1841. Moving to St Petersburg, he had studied navigation on the Volga and its improvement by steam and published a ‘valuable treatise’ on its river traffic and management. He was to set off with Thomas, who only mentions him very occasionally in his journals/diaries in his first year of travels (1847), and never once in his two subsequent books, and it is impossible to know just how much they travelled together.11 We do know that Austin was back in St Petersburg in January 1848 to marry an Adele Carlquist.12

On 4 October Thomas wrote to thank Buchanan and, through him, Nesselrode ‘for his extreme kindness’ in procuring the Emperor’s ‘most gracious permission and for obtaining the valuable papers and letters so necessary for our [italics added] journey’. Having received through Nesselrode the Emperor’s permission to submit a selection of his work, he sent off forty-nine folio watercolours, particularly of North Wales (a popular subject for English artists at that time), a few of England, southern Italy and Sicily, and a very few of Greece, Egypt and India.13 And he added, in his second letter to the Emperor:

Having had the honour of painting some pictures for her Majesty the Queen of England and some of my works having been selected by Her Majesty the Queen of Prussia [we have no record of these]14 permit me to solicit the patronage of your Imperial Majesty with the hope that your Majesty will condescend to make a selection from my works.

The perfection to which water-colour painting is at present brought in England [he may have been thinking of Turner, Cozens and Girtin] will perhaps be an excuse for my suggestion to Your Imperial Majesty that some of my works might be of great value as studies for the students in the Academy.

The funds which arise from the sale of my pictures I propose to expend on my journey through Siberia (for which your Imperial Majesty has graciously accorded me permission) …

With sentiments of Profound respect for your Imperial Majesty I subscribe myself

Sire,

Your Imperial Majesty’s most devoted and most faithful servant.

Unfortunately, the Hermitage, to which the Foreign Ministry sent on the drawings as arranged, pronounced them to be ‘lacking the quality which one must expect from English artists in the area of watercolours’. And (somewhat contradictorily) ‘although this significant collection of drawings by one artist is remarkable for uniformity [of style], it deserves nonetheless some attention.’ When the Emperor learned the opinion of the Hermitage, he ‘did not express His Supreme wish to acquire any’.

But Nesselrode nonetheless advised Buchanan that the Minister of the Interior had been invited ‘à faire les dispositions nécessaires’ so that on his distant voyage Mr Atkinson would meet on the part of the administrative authorities all the assistance and facilities that he could need. That must have been wonderful news to the prospective traveller.

There was, however, another very important development for Thomas in (or perhaps near) St Petersburg. He had met a young Englishwoman, Lucy Sherrard Finley, then twenty-nine, eighteen years younger than himself. For eight years she had been governess to Sofia, the only daughter of a Russian general; she was also from the North of England, in her case County Durham. According to the Protestant Dissenters’ Registry, implying that her parents were either Baptists, Congregationalists or Presbyterians, she had been born on 15 April 1817 in Vine Street, Sunderland, a shipbuilding port to which the family had moved from London, and was the eldest daughter (and third child of ten) of Matthew Finley, a schoolmaster originally from London, and his wife Mary Anne Yorke, daughter of a London perfumer, William Yorke. They had married in 1810.15

The 1841 census finds the family – with Lucy already in Russia – back from the north and living in Stepney, in the East End. ‘Being one of a large family’, Lucy was later to write, ‘it became my duty, at an early period of life to seek support by my own exertions’ and at twenty-two, if not earlier, she was ‘a dealer in toys and jewellery’ in the East End, probably with her own shop, thanks to a £500 legacy from a great-uncle. Then Russia beckoned, not really a surprising destination for her at that time: English, Irish and Scottish governesses were very popular there from the end of the Napoleonic Wars right up to the 1917 Revolution, their pay and social status distinctly better than in England, and ‘their total numbers must be reckoned in thousands rather than hundreds … a familiar institution in upper-class Russian society’.16

Lucy’s Russian family was by no means an ordinary one. Her employer, General Mikhail Nikolaevich Muravyov, came from a large and distinguished family, one of the oldest in Russia. Both his father and grandfather had been generals and high officials, and two elder brothers were also, or became, generals: one of them, Alexander, one of the Decembrist conspirators, was in Siberian exile but was later pardoned and made both general and governor.17 Lucy’s employer became close friends for a time with the future Decembrists and therefore had been implicated in the rising and imprisoned in the St Peter and Paul Fortress for nine months, but had cleared himself and been exonerated.18 He had married Pelageya Vasilyevna Sheremetyeva, of an immensely wealthy family, by the end of the eighteenth century ‘the biggest landowning family in the world’, ‘almost twice as rich as any other Russian noble family excluding the Romanovs’,19 and she was the sister-in-law of another Decembrist, I.D. Yakushkin.20 After three sons, a daughter, Sofia, was born in Grodno, now in Belarus, where her father was governor of the province for a few years, then governor of Kursk, after which the family returned to St Petersburg. And there in 1839 Lucy began her eight years as governess to the six-year-old, fair-haired Sofia (1833–1880), who had a ‘peaceful and comfortable’ childhood.21

Of Lucy’s appearance we know very little, except that she was petite and dark-haired and must have been a delightful young woman, judging from her own memoirs written many years later. And Thomas fell in love with her. But he was surely in a quandary, torn between Lucy and the travels on which he had determined and for which he had effectively received the Tsar’s authorisation. Perhaps Lucy encouraged him to choose the latter, agreeing to marry him after his return, possibly with the promise of future travels together.22

Meanwhile, Buchanan, as British chargé d’affaires, wrote on 30 October about Thomas to Lord Palmerston, then Britain’s Foreign Secretary. It seems that the ambitious traveller was beholden to the 11th Earl of Westmorland, a soldier and diplomat, then British Minister Plenipotentiary to Prussia (perhaps Thomas had originally met him in Berlin). It was Westmorland who had requested Buchanan to intercede with Nesselrode for the Emperor’s permission and had recommended Thomas ‘to the protection of Her Majesty’s Legation’. Buchanan also mentions Austin in his letter to Palmerston, though not by name, as an Englishman for some time resident in Russia, notes that the two intended to penetrate ‘as far as possible into China’ and therefore called Thomas’s attention to ‘several points of political and commercial interest on which Her Majesty’s Government might be glad to receive information, and he has promised to bear this in mind and report upon them … on his return to St Petersburgh’. Was he therefore to be a spy? We shall see.

His open passport from high level was to prove an enormous blessing. Not only did it mean that he did not need a new passport for every stage of the journey but that he was assured of immediate relays of horses at the post-stations en route (every fifteen to twenty-five miles apart). Post-stations existed not only to deal with postal matters but to provide horses, sledges or carriages for travellers. To hire a horse a traveller was required to produce his podorozhnaya or government pass. Thomas probably had a ‘crown’ podorozhnaya, given to government officials and privileged individuals, requiring no payment,23 and a government order could reserve horses in advance for important travellers.24 He was to find that as a rule post-stations provided only hot water and no food, so he had to take it with him. Everything was to be a new experience.

He left St Petersburg by sledge, travelling south to Moscow in mid-February 1847, and found the road very bad. The amount of traffic had cut such deep holes that his sledge descended ‘every few minutes with a fearful shock’. Three days later he reached Moscow in a great snowstorm, and on 5 March, after fifteen days there, set off east at 4pm (the diaries he began to keep are full of precise timings of arrival and departure).25 ‘The Minister’ in St Petersburg had arranged for a postilion from the Moscow post office to go with him as far as Ekaterinburg in the Urals, and he sat with the driver. Thomas himself travelled with a deerhound (for reasons unspecified) and presumably with Austin in a vozok, essentially a long, windowed box mounted on a sledge, but too big for the horses to drag it over the ridges so that, writes Thomas, it descended ‘with a tremendous bump which sends the head of the unfortunate inmate against the top with terrible force. In fact after a second day’s travelling, I came to the conclusion that my head was well-nigh bullet-proof.’

He took with him a small gilt-edged gazetteer, three inches by almost five, printed in London at Temple Bar. Its leather cover, with a strap to fit into a slot, is now in bad condition with many worm or insect holes, but the back cover’s gilt-stamped four-inch and comparative ten-centimetre rule are well preserved, as is the inside. It contains an astonishing amount of printed information of use doubtless to many British citizens but hardly to him. Then come twenty-four blank pages covered first with Thomas’s itinerary, and after them, with tiny pencil-writing filling each page, basically a journal of the following year, 1848. Confusingly, he heads many of those entries ‘1847’, probably having left blank pages for 1847 entries which he never inserted. After this follows seven-eighths of the book: ‘Literary and Scientific Register, and a COMPENDIUM OF FACTS’: 228 pages in all; and of course a detailed index, at the end of which the last entry reads: ‘Witnesses, Rate of Allowance to’. Although most of this information would have been irrelevant to Thomas, the practical sections such as antidotes to poison, and astronomy when he was lost, could have been invaluable.

He started his journal entries with only one line of either departure or arrival per day, extending them gradually through the year to complete sentences or paragraphs of some twenty or so lines, basically descriptions of the scenery – albeit with idiosyncratic grammar, scarcely any full stops or commas, and misspellings (‘ordered’, for instance, is always ‘ordred’). Russian proper names of people and places inevitably gave him trouble, and he transliterated as best he could. This first journal, in faint pencil, suggests that he must have had very good eyesight, particularly if he was writing by the light of a candle or camp fire. What is surprising is that he could write in his two books years later long descriptions based on such relatively short notes, although the later journal entries are certainly very much longer.

He set off east along the Vladimir Highway, known colloquially as the Vladimirka, a wide track through a vast open landscape. Nearly 200 km long, it had been in use since the Middle Ages. As Siberia became a place of exile the Vladimirka began to be somewhat synonymous with the passage of prisoners on their long way east, often entirely on foot.

He reached Vladimir with its five-domed cathedral and nearly two dozen churches ‘at 9 oclock’ the day after leaving Moscow but, with –15º C of frost, sketching was impossible, so the horses galloped on to reach Nizhny Novgorod on the Volga, 230 km and twenty-four hours later. He was shown into a sort of inn on the steep riverbank, hardly a pleasant foretaste of what was to come. Upstairs several large rooms were divided by wooden boards into ‘pens or private boxes in a filthy condition’ with hardly any furniture and no mattress, pillows or sheets provided for the bare wooden bedstead. Undaunted, Thomas rolled himself up in his fur and fell asleep, despite the angry and audible voices on one side. Next morning he paid his respects to the Governor, Prince Yurusov, and was invited to return to a dinner party. Thomas wanted to travel without delay, but the Prince insisted on the invitation and at least Thomas, with virtually no Russian, had the good fortune to find the Princess spoke excellent English.

Kazan, the capital of the Tatar khanate until Ivan the Terrible’s conquest in 1552, was the next stop about 360 versts east along the frozen Volga. Four horses pulled the vozok at a furious pace along the ice. At one point they got stuck on the high steep riverbank and had to be rescued by a long caravan of sledges which unyoked three of their horses to help. A few versts further on the driver pulled the horses round sharply to avoid some tree stumps but they were on the brink of the bank, which was hidden beneath deep snow. Down they all plunged with a fearful crash that broke all the vozok’s windows, and Thomas hit his shoulder so hard that he thought it was dislocated. Neither the driver nor the postilion was to be seen but, struggling to the other side of the vozok, Thomas found a pair of legs sticking out of the snow, pulled out the postilion and then unearthed the driver – fortunately unhurt among his horses in the deep snowdrift. The horses were laboriously extricated but the vozok was virtually wrecked, although a good length of rope enabled them to proceed haltingly to the next station and a four-hour repair. Thomas was in despair to find his two mountain barometers26 were broken and other things damaged – a bad beginning.

They reached Kazan in the early morning two days after leaving Nizhny Novgorod. Again Thomas had letters to the Governor, General Bariatinsky, and now to his lady as well, and was ‘very kindly received’. The town was dominated by its picturesque Kremlin and churches and minarets above the Volga. He spent two days ‘most advantageously’ with several of the university’s professors. Advised not to delay as he would find no snow further on, he set off again, soon to find signs of a rapid thaw. The road became so bad that progress was very slow. Six horses now tried to drag the sledge forward and when they found snow in the woods they were able to gallop on. But then came another breakdown and once again the sledge had to be roped together. A German-speaking officer at the scene invited this English traveller to dinner at his father’s house in the next town and oversaw his baggage transferred to a kibitka (covered wagon). After midnight the horses were once more galloping along a frozen road, and then they were blessed with two days of heavy snow.

Three mornings later he was in Perm, at last in the Urals region. In an hour, having changed horses, they went off again and, despite pouring rain and a night as dark as pitch, covered the next twenty-five versts in only an hour and a half. (Times of departure, arrival and the length between them are constantly cited by Thomas. He seemed obsessed by speed, presumably because he was aware of the great distances. A hundred years earlier, the average was about 35 km a day.)27 With the rain still heavy, he was advised at the next station to change to a ‘post-carriage on wheels’. However, after a long dispute enlivened by a heavy whip, six horses were harnessed to the sledge, and ‘with the rain still pouring down and every hour making the road worse … in many places it was with great difficulty that the horses could drag us along’.

At midday they reached Kungur, ‘celebrated for tanneries and its thieves’, one of ‘several [post-] stations along this part of the road notoriously bad, demanding unceasing vigilance from the traveller’. A number of men gathered round Thomas’s sledge, his deerhound jumped out and the postilion gave it some water. The dog quickly disappeared. The men standing around all swore that they had never seen it but Thomas noticed two men near a ramshackle building and, taking a pistol from his sledge, he put it in his pocket and followed them into a stable-yard, where he found a third man. He gave a whistle to which came an answering whine, then a bark through a door, but as Thomas advanced towards it the three ‘black-looking scoundrels’ moved to block his way. Two barrels were quickly pointed at them, and, as Thomas opened the door, the deerhound rushed out, growling loudly at the three thieves who put up no more resistance.

At last, after thirteen days’ journey from Moscow, he (and probably Austin) reached Ekaterinburg at Easter time, 1847, at ‘10 oclock at night’28 through thick fog and heavy rain. After a good night’s sleep in this, the largest town in the Urals then and now, named after Catherine (Ekaterina) I, he delivered his letter from the Minister of Finance to the ‘Chief of the Oural’ (his spelling throughout, a direct transliteration of the Russian name for Urals) who received him cordially and placed him in the care of a fellow Briton in Russian service for ten years with an ‘amiable little wife’. Thomas thus felt at home, able to speak his own language, and was invited by ‘the general-in-chief’ to ‘dine and see the ceremony of kissing’, a tradition at Easter, which some fifty officers attended. He was to stay in the town for three weeks ‘among kind and hospitable people, acquiring much useful information’ for his future travels in the region.

The town appealed to him with its beautiful large lake overlooked by big mansions set on a high hill.29 Wealthy merchants and mine owners had ‘built themselves mansions equal to any found in the best European towns’, decorated and comfortably (if not luxuriously) furnished with excellent taste, with usually large conservatories containing fine collections of tropical plants and flowers, surprising for this part of the world. One mansion, ‘of enormous dimensions’, was built by an immensely wealthy man who had started as a peasant and made a huge fortune from gold mines. Thomas found that its large and well laid-out gardens were open to the public in summer and made for a ‘pleasant promenade’. There had been an excellent collection of plants in its greenhouses and hothouses, but they had been neglected for many years, since the two sons-in-law who had inherited had been banished to Finland for having flogged some of their employees to death.

He was to be met with much kindness through the Urals and he records his grateful thanks in his first book. Interestingly, he found little difference between the wealthy class of England and that of the Urals: here ‘the ladies handsomely clad in dresses made from the best products of the looms of France and England; and [a traveller from Europe] would be welcomed … on all occasions, with a generous hospitality seldom met with elsewhere. If asked to dinner … [the repast] would not disgrace the best hotels of the same countries’, and he found fish and game ‘most abundant’ and luxuries from far distant countries not wanting, while the finest wines were ever present, ‘the only drawback … being the quantity of champagne the traveller is obliged to drink’. A far cry from his own background, yet he seems to have carried it off very well. Where did he learn how to behave? Probably from observation and his native intelligence. Perhaps he was a ‘born gentleman’.

He found the balls elegant ‘and conducted with great propriety, and they dance well’, while the older generation spent a lot of time at cards, thereby ‘risking much money’, and he greatly regretted that the young men were also much addicted; while he was there, indeed, one young officer shot himself because of his losses. The ladies also spent much time at the card table. Thomas was once assured that, while in England there were the daily papers, monthly periodicals and unrivalled literature as well as perfect freedom of speech, ‘if we had such things to occupy our minds, we should not care for cards’.

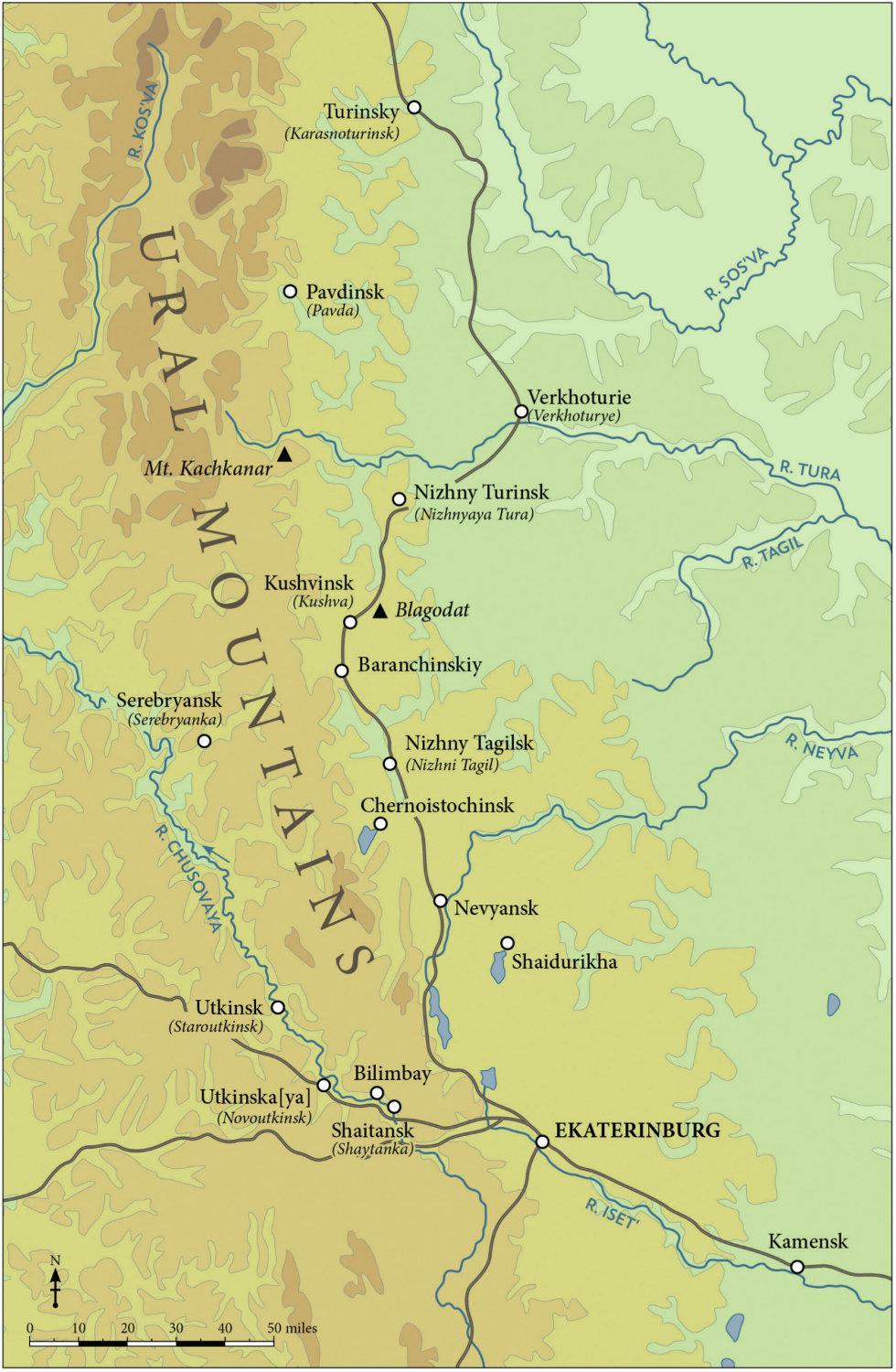

Map of the Ural Mountains

Although he was to write nine chapters about his time in the Urals (more than he gives anywhere else in his first book), he describes the many parts he visited but never gives an overall picture of that mountain chain which, since the time of Herodotus, has been regarded as the obvious boundary between Europe and Asia: the only north–south geographical feature (other than the Ob-Irtysh river system some 500 km further east) to bisect the world’s largest plain, embracing all Europe and Western Siberia; it drops gently to the west and sharply to the east. Even then the Urals are not so much a mountain chain as a series of parallel north–south ridges.30 Known in the Middle Ages as Cingulus mundi (‘the belt of the world’) – the word ‘Ural’ comes from the Tatar language meaning ‘stone belt’ – they form a range up to 150 km wide stretching over 2,000 km from Arctic tundra to arid Kirgiz or Kazakh steppe, but with an average height of only 400–500 m and individual heights of less than 2,000 m, so that today’s travellers through the southern Urals (where the Trans-Siberian railway now runs), like Thomas before them, are disappointed to find only undulating hills.31

They have been regarded as some of the oldest mountains on earth, far older than the Alps, Andes, Rockies and Himalayas. And the Southern Urals particularly have yielded an astounding treasure house of minerals. ‘Nature has been most bountiful’, wrote Thomas, ‘with seemingly inexhaustible iron and copper ore, gold and silver … masses of malachite as well as platinum, porphyry, jasper and coloured marbles plus 10,000 versts of thick forest’ which provided the huge amount of charcoal necessary to smelt the iron ore. Omitted from his list were emeralds (first discovered by some children), amethysts, topaz and other stones of the Urals which he was to see being cut beautifully. And there were diamonds too.32

The modern history of the Urals really begins in 1558 when Ivan the Terrible leased to the spectacularly successful Stroganov family, trading in salt and furs, nearly ten million acres along the Volga’s main tributary, the Kama, up to one of its own main tributaries, the Chusovaya, which rises in the eastern Urals. A decade later, Ivan more than doubled that lease by adding the lands along the Chusovaya itself so that the Stroganovs became ‘the richest private landholders in Russia’.33 In 1581 they sent a Cossack band under its chief Yermak, originally a pirate on the Volga, up the Chusovaya, the shortest route across the range, into Siberia to begin the Russian conquest of that huge landmass to the Pacific.

The Urals’ next leap forward was in Peter the Great’s reign when the son of a peasant blacksmith, Nikita Demidov (1656–1725), set up Russia’s first good smelter in Tula, south of Moscow. It became the Russian army’s main supplier with contracts for 20,000 flintlock muskets, producing arms and munitions twice as fast and twice as cheaply as its competitors, and in 1702 therefore Peter gave Demidov a foundry at Nevyansk in the eastern Urals, the foundation of a great iron empire of 10,000 square miles, using the Chusovaya river to carry ‘barge loads of iron and munitions into the heart of European Russia’.34 It could be said that both the Russian–Swedish war and the Second World War were won in no small measure thanks to the Urals’ iron ore.

By his death twenty-three years later (now Prince) Nikita Demidov had become an armaments tycoon, employing thousands of workers.35 ‘Because there were few noble estates in Siberia (in 1830 only sixty-five in Western Siberia), mostly round the Urals, there were consequently very few serfs, the majority of peasants being “state peasants” living on land owned by the state and paying dues to it.’36 Many of Demidov’s workers were sent abroad for training so that there were serf-engineers ‘in highly skilled and managerial positions’,37 becoming ‘some of Russia’s best foundry masters, metal workers and gunsmiths in the eighteenth century’ (if not in the nineteenth century too).38 The scale was extraordinary: by the end of the eighteenth century, the Demidov industrial empire included fifty-five plants and factories producing 40% of Russia’s total iron and cast iron, and the Demidov dynasty was the wealthiest family in Russia after the Tsar,39 in Thomas’s time owning just over 3 million mineral-rich acres (12,200 sq. km), more than the size of his native Yorkshire.

Nikita’s equally able and industrious son Akinfiy added eight new steel works and arms factories and began to mine in the Urals and West Siberia (finding rich deposits of silver and malachite in the Altai mountains) for which Peter granted him and his brothers hereditary nobility. Akinfiy’s son, Prokofiy, now the third generation, turned on his inheritance at fifteen from being a reckless squanderer to a capable manager, modernising his plants, marrying the heiress of the Stroganovs’ Siberian fortune, and giving lavishly to good causes (including four bridges in St Petersburg). His Moscow mansion is now occupied by Russia’s Academy of Sciences. Through this remarkable dynasty Russia became the leading producer of pig iron (smelted iron ore) in continental Europe, producing as much as the rest of Europe combined.

With such extraordinary mineral wealth, particularly iron ore, it is not surprising that here developed one of the world’s oldest industrial regions and the most important industrial area of the Russian Empire. Ekaterinburg was its administrative centre, headed by a general of artillery. Thomas found the Berg inspector or chief Director of Mines (to whom an official letter had been sent from St Petersburg enlisting his help) ‘one of the most intelligent mining engineers in the empire’, and to him and to his ‘amiable wife’ he was ‘indebted for many acts of kindness, as well as for some of the most agreeable days he was to spend in the Altai’. He was to visit many of the zavods in order to sketch them, but not one image of them appears in his books nor is any watercolour known.

Nonetheless he was obviously greatly interested in – and impressed by – the Urals’ natural wealth and its exploitation, and he wrote in very positive terms of the area’s metallurgical industry. He found the government’s ‘mechanical works’ were on a huge scale and ‘fitted up with machinery and tools from the best makers in England’, all superintended by a ‘good practical English mechanic’ for the past fifteen years. This man was credited with the machinery of the Mint which coined much copper money sent every year to European Russia, while the gold and other precious metals of the Urals were smelted in another building and sent to St Petersburg as bars. And close by in a ‘factory’ owned by the Crown the semi-precious stones of the region were turned by skilled peasants into pedestals, vases and columns of the highest quality. But wages were paltry in the extreme: one man inlaying foliage into jasper vases in a style ‘not excelled anywhere in Europe’ was earning ‘three shillings and eightpence per month’ (Thomas’s italics) plus two poods of rye flour to bake as bread. To be fair, however, the cost of living was extremely low.40

II. Travels in the Urals

Thomas was by no means the first British citizen to visit the Urals. ‘English mechanics have been employed in the Oural’, he wrote, ‘from a very early period of its mining operations’, and one or two became well known for their eccentricity, not just in their own generation. Later, in 1853, the Atkinsons found there were several English mechanics in Ekaterinburg, and Lucy noted that they struggled to outdo each other in splendour: ‘One has his carriage and his tiger, therefore does not deign to associate with his countrymen who have not. The General [Glinka] patronises this family, and it is whispered, on account of the good fare he gets.’

Thomas tells a story about a British citizen in the Urals, who was very stout and loved a good dinner. His job was to inspect the works and machinery at the government zavods. On one particularly hot day he was travelling in the southern Urals and had dined very well. His tarantas (a four-wheeled light carriage) had stood all day in the blazing sun and was now like an oven. As he liked his comfort, it had a well-stocked compartment for food and wine which could be adapted into a comfortable bed. That night, the inspector found it impossible to sleep in the heat and so took off all his clothes and covered himself with a sheet. The carriage set off and with daylight they reached a post-station where the horses were changed while he slept on. The servant and yamshchik, seeing he was happily asleep, decided to have a glass of tea in the station, but while they were there something frightened the horses and off they galloped.

The inspector, tossed from side to side on the rough road, woke to find himself alone, pulled at frightening speed by four unstoppable horses abreast. It was impossible to jump out. The speed slackened when they reached a steep hill but he knew that on the other side an even steeper hill downward awaited him, four versts long. He sprang out near the top – fortunately surviving without injury. The horses went on at full gallop, leaving him alone in the forest with no shoes or stockings and no clothes except ‘one scanty linen garment’ (presumably some sort of pantaloons), surrounded by a horde of thirsty, humming mosquitoes. Fortunately, a peasant woman on horseback came near but stopped, shocked at seeing the strange figure.

‘Come here, matushka [little mother]’, he said. She summoned up enough courage to ask what he wanted. ‘Your petticoat’, he replied. ‘I have only one’, was her faint reply, ‘take it and spare me’, and she dismounted and handed it over. Putting it on, he walked along the road and soon his servant and the yamshchik arrived at full gallop, relieved to find him safe, but, wrote Thomas, ‘could scarcely contain their gravity at sight of his extraordinary costume’.

A Tarantas

On the great post-roads the Atkinsons travelled thousands of miles either by tarantas (their luggage piled beneath and behind them) or, in winter, covered sledge, by far the quickest way – particularly at night when the snow was crisper and their bell would alert other travellers. The four-wheeled, hooded, springless carriage was usually pulled by three horses – the troika – but occasionally up to seven.

After several days in Ekaterinburg, Thomas began his travels in the Urals. He resolved to journey down part of the 600 km-long Chusovaya river. Remote as it is, this river is important in Russian history, not only as Yermak’s route across the Urals in 1581–2 with his band of Cossacks to begin Russia’s occupation of northern Asia, but because it also provided a heaven-sent route downriver to Perm on the Kama – where Thomas had had an overnight stop on his way east – and on to the Volga for the products of the Urals’ seemingly inexhaustible mines.

The first river-port on the Chusovaya was built in 1703 on Peter the Great’s orders to exploit the Urals’ ores, and already by Thomas’s time an immense amount of iron, often cast into ingots, had been transported by experienced bargees downriver to Perm on great wooden barges, each carrying as much as 200 tons. It was particularly in the spring floods (mid-April to mid-June), when the water level was four to five metres higher, that the barges (sometimes whole caravans) set off, but the fast, winding river was nonetheless very dangerous. Some 200 sheer limestone rocks, many with individual names, rise separately – and scenically – from the river banks in its middle reaches, some over 100 metres high. This was naturally the stretch that Thomas wanted to visit and to paint. Picturesque perhaps, but these cliffs were a major hazard to navigation. All too often barges crashed into them.

Thomas left Ekaterinburg the morning after the ice on the Chusovaya broke up, along bad roads, sometimes almost impassable. ‘Even with five horses yoked to a very light carriage, we were five hours travelling twenty versts.’ Their immediate destination was the iron-works of Count Stroganov where they were entertained ‘most sumptuously’ and he slept on the same sofa where the Emperor Alexander had rested the evening of his own visit twenty-four years before. The next morning they were taken to the nearby pristan where many workmen were busy loading nearly forty barges with bar and sheet iron for the great annual fair at Nizhny Novgorod on the Volga. They then ‘descended the river rapidly’ – thirty versts in two hours – to the pristan of Utkinsk, where most of these possibly unique barges (Thomas calls them barks or barques) were built.

It was now a scene of great activity, there being four thousand men in this small village, brought from various places (some from villages 500 and 600 versts distant), all diligently engaged in loading the vessels with guns of large dimensions … also with shot, shell and other munitions of war … destined for Sevastopol and the forts on the Black Sea. These munitions of war are made with great care and accuracy under the superintendence of very intelligent artillery-officers.

The barks are built on the bank of the Tchoussowaia [Chusovaya] … flat-bottomed … with straight sides 125 feet long … a breadth of twenty-five feet, and … eight to nine feet deep; … [with] the ribs of birch-trees … and the planking of deal; … entirely put together with wooden pins … The decks are … not fastened to the barque … as they are often sunk in deep water after striking the rocks. When this happens, the deck floats, by which the men are saved. Each barque, whose cargo has a weight of 9,000 poods, requires thirty-five men to direct it; and one with a cargo of 10,000 poods has a crew of forty men. Oars, usually of forty-five to fifty feet long, with strong and broad blades, guide it at the head and stern; and a man stands upon a raised platform in the middle to look out and direct its course.

It was now mid-April: the weather changed dramatically, and rain and a strong wind produced a great flood which swept large masses of ice down the river at speed, endangering the barges. Seven belonging to a merchant from Ekaterinburg were already laden with tallow, ready to descend the river; two of them were badly damaged by the ice. Thomas was invited to see the priest bless the undamaged barges before their voyage, a ceremony on board marked with much solemnity. A feast was then provided by the merchant, and in an hour vodka had obliterated the memory of hard work and the company ‘were embracing each other with the fervour of brothers after twenty years’ separation’.

Next morning the storm and flood had subsided, the sun shone, Thomas’s friends at the pristan provisioned him well (adding some bottles of rum and Madeira) and he and his crew set off down the Chusovaya, propelled by the current ‘at a great speed’ with the helmsman offering up a prayer for their safe voyage ‘down this rocky and rapid river’. One side was flat, uninhabited meadowland with occasional clumps of pine and birch, the other all hills and almost impassable pine forest and morass, particularly so with all the streams then in furious spate. Some parts were very pretty, Thomas thought, but he regretted seeing no bear or elk, which he had been told were numerous here.

With his stonemason career behind him, he noted (as he was often to do) the rocks he saw: here in some places the once-horizontal limestone strata had been forced upwards by tectonic action into extraordinary forms, with other rocks pushed through them. After nine hours covering thirty-five versts on the river, it was dark and snowing, but a light from an iron-works furnace led them to the director’s three-roomed house (with a tiny front door only four feet high and two and a half feet wide). Thomas showed the director his papers ‘which at once procured me every attention’. The same procedure was to become axiomatic throughout his travels. A horse and cart brought his luggage up to the house, and a boy brought him hot tea and preserved fruit. He put on a dry pair of boots (perhaps he always travelled with two pairs) but could not change his clothes as the lady of the house was continually in and out of the room. And through a doorway he noticed six or seven pairs of inquisitive young eyes, ‘wondering no doubt what sort of animal had invaded their quiet abode’. When their mother, whom he wanted to win over, re-entered the room with her youngest son, Thomas (a father himself) proceeded to toss him in the air, to the family’s astonishment and the mother’s pleasure.

‘Curious rocks on the Tchoussowaia’

In his first year of travels Thomas spent many days on the picturesque Chusovaya river, flowing from the southern Urals and dominated by high cliffs of very individual shapes. He produced twenty-eight sketches and would present Nicholas I with ten small watercolours of the river, which are now in the Hermitage.

What followed was a foretaste of Uralian hospitality. No conversation was possible (so Austin cannot have been with him), and he had to resort to his Russian-and-English dictionary, but all was good-humoured. At supper Thomas was placed at the head of the table with his host at one side, and he expected the wife to sit down opposite him, instead of which she sat down at the far end of the room. Thomas ‘declined to partake of their hospitality’ unless she sat with them – and won. His hosts urged him to eat and drink, with several wines on the table. He was introduced to nalivka (a strong, vodka-based liqueur) which he claimed every good Siberian housewife made from the local abundance of berries or fruit. He tried a glass, ‘the colour of claret, but the flavour vastly superior’, and sampled four more – ‘most delicious’. His host produced a bottle of champagne and two, not three, glasses on a tray, for the two men. Their guest, however, presented his filled glass to the wife, much to her surprise and pleasure, and when a third glass was brought, the three of them emptied the bottle together. His hostess produced various Siberian (sic) liquors, all of which she insisted he tasted (à la russe, i.e. draining each glass). Finally his host appeared with more champagne. Only then was he provided with a sofa to sleep on: he does not say with what degree of sobriety.

At seven o’clock next day he was brought tea and bread, then shown round the iron-works by his host (a lot of bar iron was being made and sent by barge to the Kama) and returned to a breakfast ‘of [once again] Siberian fare: fish-pasty, meat, several sorts of game, and tarts made of preserved wild strawberries, with plenty of their excellent nalivka; and it finished with a bottle of champagne’. Thomas presented the eldest child with ‘one of my illustrated English books’, writing his name inside so that it would be ‘preserved with great care, and most probably handed down to the next generation’ – and who knows, still remains in this remote place.

They all sat down for two or three minutes of calm or silent prayer, a custom which continues today, then kisses were exchanged and he resumed his journey. His host indicated that he and a friend wanted to go down the river, and Thomas was glad to give them a lift. After only two versts his host told the boy of the crew to fetch a bottle and glasses and once more the champagne flowed. His host’s sledge was waiting for him on the riverbank – he had come only to show yet more hospitality.

On one side of the river soon appeared very high and craggy rocks, and once two large caverns, a hundred feet above the water. Thomas told the boatmen to stop and was put ashore, but after several falls he was compelled to stop climbing. He had hoped to find something in them worth drawing. Nonetheless his first book contains an engraving of the entrance to one cavern: two tiny figures dwarfed at its mouth, one seated sketching, show the scale, which must surely be greatly exaggerated. Again he noticed the strata’s contortions, some curved, some triangular, some almost perpendicular, ‘giving great variety and picturesque beauty to these wild gorges’.

They arrived at Shaitansk pristan after a snowstorm of some hours and a very cold and unpleasant voyage. Three hours earlier ‘six poor men were drowned’ when trying to cross the Chusovaya in a small boat, and although several hundred people saw what was happening they could do nothing. And soon after Thomas’s arrival another accident occurred downriver: the church bell sounded the alarm and people ran off fast with small poles. A large barque, loaded with iron, had struck a rock and sank immediately except for the deck, so the crew was saved.

Thomas and his own crew were ready to depart at eight o’clock the following morning, but a great snowstorm blew for some hours. He took shelter in the nearest building, a ‘respectable cottage’, where two kind women, understanding his plight, sat him down and brought him some preserved fruit and cedar nuts ‘much liked here’41 until the snowstorm lessened. Next day he walked up the bank, telling the men to follow him with the boat, sketched three views (which he considered would be ‘exceedingly beautiful’ in June and July when the many different shrubs and flowers would be in bloom), and, on reaching the next pristan, was greeted by his hospitable host of Utkinsk, who easily persuaded him to return to his home, promising to send him back in a boat. They set off in his tarantas: ‘to make it more comfortable, a quantity of straw was put into the bottom, covered with a rug, and several pillows were placed at the back’. Six horses pulled the vehicle, four only yoked. They drove through increasing dusk and then night through a ‘wild and gloomy’ forest with magnificent pine trees, ‘giants of the forest’, hundreds of dead trees shattered by lightning and many saplings, and only after midnight were given a warm welcome.

Next morning, as promised, he was rowed back to Shaitansk through sunshine; then heavy rain and sleet almost blinded them all and he arrived ‘completely drenched, and almost frozen with sitting eight hours in an open boat’. Early next day he set off with a local hunter towards the riverside village of Ilimsk, assured of ‘some magnificent scenery’: ‘a deep and narrow gorge’ with dramatic dolomite peaks and ‘some remarkable rocky scenes’ with limestone rocks broken and twisted, some into vertical jagged strata. He showed his coloured sketches to a new overnight host, continued downriver through a spectacular limestone gorge, explored two big caverns with pine torches, ‘wrote up my journal42 by the light of our blazing fire’, and wrapped himself up in his cloak for his first night’s sleep in the open air. Nearing Utkinsk-Demidov pristan where the whole output of the Demidov mines, having been sledged here, was put on board for Nizhny Novgorod and St Petersburg, the river’s rugged character gave way to a forest and the river widened from two versts to three. Sheltered by high hills, green meadowland lay on one bank, ‘a fine crop of rye’ was springing up on the other and birch trees were ‘bursting into life’.

He showed his papers to prospective hosts along the way – hospitality was always granted – and on one occasion given glass after glass of tea, which enabled his host and his host’s friend to ask ‘a series of questions, few of which I could understand. They talked very fast … [I said] Yes! or No! in Russian, as the case appeared to require. At length I got tired of this, and began an oration in English, speaking as fast as I could which stopped them immediately’. But the moment he stopped they began again, and only by reciting poetry (probably remembered from school) could he silence them.

About 10 o’clock supper was announced and three women of Amazonian proportions, wearing very short shifts with red handkerchiefs on their heads, produced a large, evidently communal, bowl of soup. He could, he writes, ‘endure hunger for a long time … eat black bread and salt without difficulty, but take broth … from the same soup-bowl I could not’. However, he ‘managed to make a good supper out of the next course’ – ‘a great number of boiled eggs’ – and found a wooden bench to sleep on but, now used to hard fare and hard beds, would ‘be content with whatever turned up’.

He rose the next morning at half past four, ever the early riser, and after one cup of tea was on the river again. Later he found on the bank a simple stone cross on three steps marking the site of the birth of Nikita Akinfeyevich Demidov, the third generation of that impressive dynasty. Having sketched this scene, he was brought by the steersman ‘a piece of black bread with a little salt, and a bottle of sap [tapped from the nearby birch trees] … a sweeter morsel or a better draught, I thought I had never tasted’.

After finishing the last of his twenty-eight sketches along the Chusovaya43 – ‘isolated masses of rock standing in the bed of the river’ – Thomas continued downstream to an iron-works belonging to Count Stroganov (it had once been Yermak’s base), where he found excellent quarters and spent ‘a most agreeable evening’ with his German-speaking host. Next morning the water level had risen by three feet due to a sudden thaw, and Thomas was persuaded to remain and visit the works, which produced both bar iron and a great deal of superior-quality wire which would fetch a high price at the Nizhny Novgorod fair, 800 km west. He returned to his night’s abode and ‘an excellent dinner, well cooked and well served’: many varieties of game accompanied by ‘English porter, Scotch ale, and champagne, with several sorts of Ouralian wine; of the last I tasted one kind for the first time, made from cedar-nuts – it equalled the best Maraschino’.

The weather changed again, to –6ºC, and a strong wind made it bitterly cold. Very soon they were enveloped in another snowstorm for nine hours. All that time he and his little crew sat in the open boat – his last day and night on the river, unsurprisingly ‘cold and unpleasant’ – reaching their final destination, Oslansk, only at 2 a.m. His men were now obliged to return home and Thomas ‘parted with them on excellent terms; a few roubles had rendered them happy, and, kissing my hand, they all declared they would go anywhere with me’. On parting, he headed for comfortable quarters in the house of the director of a Crown zavod on the Serebryanka river, a tributary of the Chusovaya. Of this area Thomas’s fellow countryman, the geologist (later Sir) Roderick Murchison, wrote of his own expedition six years earlier: ‘We … got into the forest, not having seen a house or hut for fifty miles. The dense wilderness of the scene, the jungle and intricacy of a Russian forest, can never be forgotten. We had to cross fallen trees and branches, and to force through underwood up to our necks.’44

Murchison, who enters the story much later, had preceded Thomas to the Urals in 1841 and, as a result, named the last of the Palaeozoic eras ‘Permian’ after the region’s ancient kingdom of Permia. Like Thomas, he was greatly impressed by the Urals’ scenery, and in one stretch on the Chusovaya he found ‘scenes even surpassing in beauty those higher up the stream, and to sketch it would require the pencil of a professional artist to do it justice’. Thomas, who quoted that in his first book, had the grace not to say that the artist had now been found.45

While on the Chusovaya he had fallen among rocks and cut his knee badly – he thought he would keep the scar all his life – and now on his way east across the Urals he began to suffer considerably both from his knee and a bad cold caught in the last heavy snowstorm. When he reached his next zavod, Kushvinsk (now Kushva), he was afraid it would develop into a fever, and the director immediately sent for a doctor who ‘ordred’ him to bed while a Russian bath was prepared for him to which two sturdy Cossacks carried him. Having been divested of all his clothes, he was placed

on the top shelf of the bathroom within an inch of the furnace – if I may so call it – and there steamed … until I thought my individuality well-nigh gone. After about forty minutes of drubbing and flogging with a bundle of birch-twigs, leaf and all, till I had attained the true colour of a well-done craw-fish, I was taken out, and treated to a pail of cold water, dashed over me from head to foot, that fairly electrified me. I found myself quite exhausted and helpless, in which condition I was carried back to bed. I had scarcely lain down ten minutes, when a Cossack entered with a bottle of physic of some kind or other, large enough apparently to supply a regiment. The doctor followed … and instantly gave me a dose. Seeing that I survived the experiment, he ordered the man in attendance to repeat it every two hours during the night. Thanks to the Russian bath, and possibly the quantity of medicine I had to swallow, the fever was forced, after a struggle of eight days, to beat a retreat.

Although still very weak, he was keen to resume his travels and was given a lift north towards the Kachkanar massif, the second highest point in the Central Urals and the furthest north he ever reached. He stopped for a few days at the Crown zavod of Nizhnyaya Tura while arrangements for his visit to Kachkanar were being made, and produced several sketches, particularly of the large lake formed for the iron-works’ water power: ‘continuous clouds of black smoke, through which tongues of flame and a long line of sparks shot up high into the pure air; these and the heavy rolling of the forge-hammers that now broke upon our ears, are truly characteristic of this igneous region’.

Such descriptions in his book are rare but he writes up at length many different landscapes and colours that he sees through his artist’s eye. On this journey, for instance:

One most splendid evening, the sun went down below the Oural Mountains tinging everything with his golden hues. From one part of the road we had a view of the Katchkanar, and some other mountain-summits to the north, clearly defined against the deep yellow sky in a blue grey misty tone; a nearer range of hills was purple as seen through a misty vapour rising from the valleys; while nearer to us rose some thickly-wooded hills, their outlines broken by rocky masses of a deep purple colour. From these to the lake in the valley there is a dense forest partially lost in the deep shadow.

Ahead of him and his two local companions on this occasion, guided by a veteran hunter, lay a tedious eleven-hour ride through dense forest, fallen trees, rocks and mud sometimes almost up to the saddle-flaps and the dreaded hum of ‘The mosquitoes … here in millions – this compelled us to make a fire and a great smoke to keep them at a distance. The poor horses stood with their heads in the smoke also, as a protection against these pests.…’

Further on, he climbed up some rocks to see

the jagged top of Kachkanar … towering far above into the deep blue vault of heaven; the rocks and snow … tinged by the setting sun; while lower down stood crags overtopping pine and cedartrees; and lower still, a thick forest sloped along till lost in gloom and vapour.

He and his companions all had rifles in case of bears. In fact, he never seems to have encountered one, but they could be very dangerous. He tells the story of two small children who wandered away from haymakers to pick fruit until they came on a bear lying on the ground and approached him, totally undaunted. For his part the bear

looked at them steadily, without moving; at length they began playing with him, and mounted upon his back, which he submitted to with perfect good humour. In short, both seemed inclined to be pleased with each other; indeed the children were delighted with their new play-fellow. The parents, missing the truants, became alarmed, and followed on their track. They were not long in searching out the spot, when, to their dismay, they beheld one child sitting on the bear’s back, and the other feeding him with fruit!

When their amazed but anxious parents called, the children ran to them and the bear disappeared into the forest. Once Thomas came across a ‘strong and active’ woman, Anna Petrovna, widely known as ‘the bear hunter’. ‘Her countenance was soft and pleasing,’ and nothing indicated her ‘extraordinary intrepidity’, yet by the age of thirty-two she had already killed sixteen bears.

Surprisingly, Thomas makes no mention of sables or other fur-bearers, but there was the perennial nuisance of mosquitoes. Once at Kachkanar he and his companions encamped but moved upward to a constant breeze in order to escape the ‘cursed pests’ and there, ‘where a breeze kept fanning us, not a mosquito dared show his proboscis’. But in the Urals forests he was often tormented by them in hordes and must have found it difficult to sketch with his bare hands under attack. He ‘tried various means to keep them at a distance – in vain’. He finally tried a device ‘much used by the woodmen’: hot charcoal in the bottom of a small sheet-iron box punched with holes, slung over the shoulder. The cloud of smoke produced might drive off the voracious insects successfully but, Thomas writes, ‘the continuous smoke affected my eyes to such a degree, that I could not see to sketch – many of the woodmen suffer from the same cause’. So he gave it up ‘at the risk of being devoured’ and was glad to find breezes to keep them off.

At the Kachkanar massif they found a ‘confused mass of rocks thrown about in the wildest disorder’, some of huge size, and scrambled over it to a small valley carpeted with plants about to flower or already blooming: iris, geraniums, roses and peonies, ‘amidst scenes of the wildest grandeur’, among ‘clumps of magnificent pines and Siberian cedars’. By the former he must mean the Siberian pine Pinus sibirica (as distinct from the far more common and widespread so-called Scots pine Pinus sylvestris) which grows slowly but can reach a great height and age: one in West Siberia’s Altai mountains was measured in 1998 at 48 m tall and 350 cm in girth, and the oldest known, in Mongolia, had a cross-dated age of 629 years in 2006.46

Across a valley they began the actual climb (Murchison had been here before him), his ‘sketching traps’ across his back, up ‘a chaotic mass of large loose rocks … under huge blocks … and further up large patches of snow’, and at last reached the summit with its extraordinary jagged crest of hundred-foot irregular columns of rock: interspersed with up to four-inch strata of pure magnetic iron ore and, projecting from the sides, cubes of iron, three to four inches square. He saw it as ‘a mountain in ruins … the softer parts having been removed or torn away by the hand of Time’.47

He climbed one of the highest crags with great difficulty – and risk – taking only a small sketchbook with him and, with his feet dangling over the edge, wrote a note to a friend (Lucy perhaps?). He found

the view to the east, looking into Siberia, …was uninterrupted for hundreds of versts, until all is lost in fine blue vapour. There is something truly grand in looking over these black and apparently interminable forests, in which no trace of a human habitation, not even a wreath of smoke, can be seen to assure us that man is there.

Summit of Kachkanar

On the way down again, scrambling over fallen rocks on an intensely hot day, they stopped for a rudimentary lunch, and Thomas filled a glass almost full of hard frozen snow on which he poured some strawberry nalivka to produce a ‘delicious’ dessert for himself and his companions, tired, hungry and thirsty.

At one zavod (Kushvinsk), south of Kachkanar, he found the officers from all the zavods around had arrived for a dance on someone’s name day, and it proved to be a jolly affair with dancing until half past two followed by supper. The next day everyone was off to a great festival at another zavod nearby. Thomas accepted an invitation to dine there, made two sketches on his ride, and was interested to observe such festivities, which included wrestling and swings. Girls with linked hands, dressed in bright colours, sang beautiful but plaintive songs. These ‘rural pastimes’, he wrote, ‘reminded me of sports on the village green in the days of my childhood’ – a far cry from his Yorkshire village of Cawthorne.

What turned out to be an unexpectedly dramatic expedition was to Blagodat, a few miles further south, a great hill still famous today for its high-quality iron ore48 and known to contain magnetite.49 On its summit was a small wooden chapel and tomb to the memory of a Vogul chief50 who was killed and his body burnt here by his people for having betrayed the iron ore to the Russians. Thomas found that, although the Urals were visible from the top, the whole view was otherwise of flat, dense pine forest. The day was fine, but he noticed a storm gathering far off, and when big drops of rain started to fall, he sought shelter for himself and his sketches ‘and colours’51 in the chapel at the summit. By now the Urals were obscured

in a thick black mass of clouds, tinged with red from which the lightning leapt forth in wrathful flashes.… For a few minutes a great dread came over me, knowing I was standing alone on a huge mass of magnetic iron, far above the surrounding country. The thunder echoed among the distant hills until at length it became one continued roll, every few minutes. I could … hear the wind roaring over the forest; then came a blast which forced me to cling fast to the monument … and made the little chapel tremble to its base. The cold gust of wind was instantly followed by a terrific flash of lightning, which struck the rock below me and tinged everything in red; at the same moment a crash of thunder … burst into a tremendous roar, which shook the rocks beneath my feet. The rain now rushed down in torrents, from which even the little chapel did not afford me protection – for through its roof the water poured in streams. This was a truly sublime and awful scene – the lightning and thunder were incessant, indeed I saw the rocks struck several times. The storm undoubtedly revolved round the mountain, no unfit accompaniment to the dreadful sacrifice once offered up on its summit.

It was astonishing that he himself was not struck by lightning.

These journeys in the Urals were seldom easy, but Thomas was always game for more. Determination and ambition drove him on. There may have been on occasion a good track or a grassy flower-bedecked valley, but all too often he had to negotiate dense and ‘interminable’ forest, low branches and fallen trees, rocks and great boulders sometimes with trees growing round them, dangerous scree and mire in which the horses sank, leaving the riders wet and covered in mud; and often the rain poured down. Sometimes the ‘roads’ were corrugated, i.e. made of tree trunks, and this had surprisingly little effect on the telegas (baggage carts), ‘made without either nail or bolt … put together with wooden pins and withes – this permits them to twist about in every way – and to suit any road, rough or smooth; but not the traveller, who is almost shaken to pieces by the jolting’. And sometimes a snowstorm stopped all progress. Yet he seems to have enjoyed it all (except for fatigue, saturation and mosquitoes – and that illness), particularly the views from the heights which sent him into raptures, above all at sunset or dawn. And he appreciated the silence of the forest ‘undisturbed by any sound except the shrill voice of the large red-crested woodpecker’, as well as the great hospitality of the zavod directors who ‘received me most kindly, freely giving me, as usual, every possible accommodation, and treating me with the greatest liberality’.

He and ‘my men’ then rode east across the Urals, visiting platinum mines near the crest, descended the east side, much steeper than the west, and proceeded to Nizhny (or Lower) Tagilsk to ‘the hospitable house appointed for strangers’, where he received from the zavod director ‘the greatest kindness and attention’ – even more so than usual – with every facility to sketch, men and horses when required, and a man who had lived several years in England assigned to accompany him wherever he wanted to go. At the time this was a town of some 25,000, and Thomas was very impressed by its many fine buildings of brick or stone (unlike the wood so often found elsewhere). He extolled the church, the splendid administrative building, the large schools, great warehouses, ‘spacious houses for the directors and chief managers [and good hospitals] and very comfortable dwellings for the workmen and their families’.52 He wrote that ‘The smelting furnaces, forges, rolling mills … are on a magnificent scale and the machines and tools of the best quality, some indeed from England’, and others made under the supervision of a very clever local engineer who had spent several years in a top Lancashire works. And he considered that ‘The manner in which these works are conducted, reflects the highest credit on the Director and his assistants in every department’.

In fact, Anatoliy Demidov, fourth generation of the dynasty,53 who had employed leading scientists from Europe to survey his territory, spared no expense in sending several talented young locals from his zavods to France and England, allowing them both generous time and finance and giving some their freedom from serfdom. Many of his workforce had indeed become wealthy men – not surprising in view of the ‘inexhaustible supply’ of magnetic iron ore nearby in an open quarry about 80 feet thick and 400 feet long – ‘material for ages yet to come’. Close by were copper mines with 300-foot shafts, and a few years before Thomas’s visit an ‘enormous mass of malachite’ had been discovered. Murchison had seen this ‘wonder of nature’ and calculated it as 84 feet long by 7 feet wide, up to 15,000 poods in weight or nearly half a million pounds of malachite. Even then, Murchison tells us, ‘it was traced downwards to 280 feet’.54 The geological interest to Murchison, however, was not so much the size but that it indicated that malachite is formed by copper solutions trickling down through porous mass to form a stalagmite within a rock cavity.

Thomas and a small party then set off on an overnight excursion to the scenic Belaya Gora (White Mountain), visiting on the way another Demidov zavod, Chernoistochinsk, busy making bar iron (bar-shaped wrought iron), ‘considered the best in the Urals’, according to Thomas known in Britain as ‘old sable-iron’ from the Demidovs’ sable mark and turned into the best British steel. They reached the foot of Belaya Gora through ‘rich, park-like scenery’ with great Siberian ‘cedars’, enormous pines (some 150 feet tall) and ‘clumps of peony in full bloom’. After another hour they arrived at the ‘beautifully sheltered spot’ (no mention of mosquitoes) already selected for the night, where ‘a huge fire was burning’, a balagan or shelter was in place and ‘carpets and a table-cloth were spread on the grass’. The hungry party was soon enjoying what had been prepared for them, not least Thomas, who found that ‘both the dinner and wines were excellent, and the London porter as fresh and foaming as the most tired traveller would wish to have it’.

Dinner over, the party ‘inclined to sleep (a universal custom after dinner in these regions, indeed throughout Russia)’ but Thomas set off with his rifle and a man to carry his ‘sketching materials’ of watercolours and brushes, water, sketchbook and bag, and sat down with a picturesque view before him of rocks and trees and distant mountains of blue and purple. Here he sketched and contemplated, becoming totally convinced that the whole range of the Urals would have once been much higher and that the original peaks were now ‘shattered, broken, and tumbled about in every direction’ under the elemental force of water which would have torn up ‘everything in its course’. This explained, he thought, what he had seen, even the enormous rocks; he had measured some and found the average 8 feet thick and one 12 feet by an enormous 43 feet.

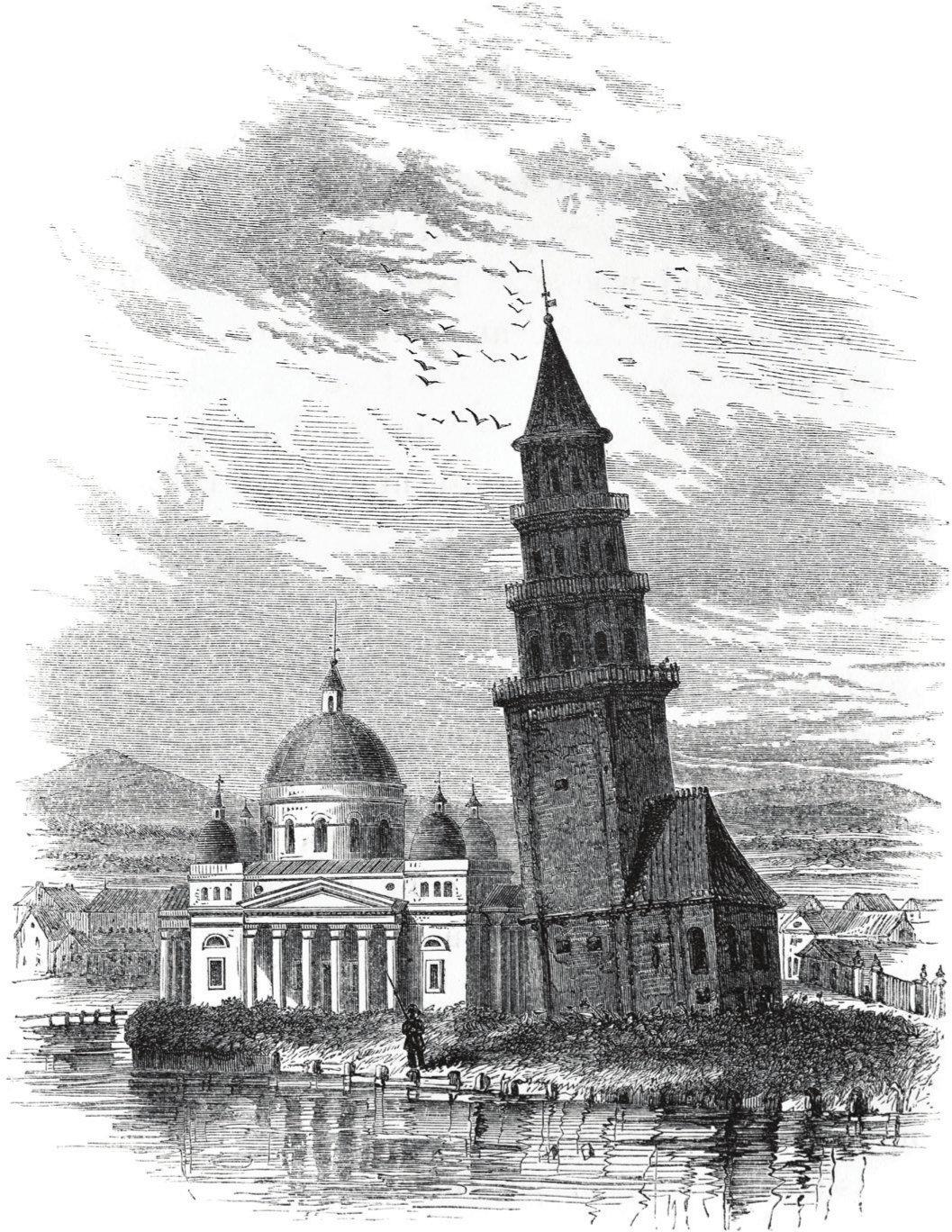

His next visit was through continuous forest to Nevyansk, north-west of Ekaterinburg, the Demidovs’ first Urals zavod. Its population had grown to nearly 18,000 and he was given a room in the castle, a ‘magnificent’ Demidov mansion where no members of the family still lived but all was provided free for travellers, welcome day or night, including ‘excellent fare and delicious wines – port, sherry, Rhine wines and champagne’. Thomas sketched the little town’s early eighteenth-century leaning tower of brick, its most famous feature, which surprisingly boasts the world’s first reinforced concrete, cast-iron cupola and lightning conductor as well as a seventeenth-century clock with clockwork bells made by Richard Phelps, the master of London’s Whitechapel Bell Foundry, known for his large bell, ‘Great Tom’, in the steeple of St Paul’s Cathedral (though none of this does Thomas mention).

The zavod here produced painted iron-ware and different items that circulated through the whole of Siberia via the great February fair at Irbit, east of the Urals, including iron-bound wooden boxes, usually painted blue or red, found in almost every peasant home. It also produced a huge number of rifles which, although they looked rough, were extremely accurate, and two were made specially for Thomas at the director’s request, one small, the other large-bore, which cost him £4 15s for the two.

He travelled on south, nearly parallel to the Urals chain, through what had once been dense forest, felled for the neighbouring zavods to smelt the ores beneath them, but now growing up again, and in the southern Urals some fifty versts south of Ekaterinburg he visited a Crown zavod and an iron-works which stood in a pretty, well-sheltered wooded valley of the Syssert river. The whole place with its church, hospitals, furnaces and warehouses had ‘a very imposing appearance’ with ‘well laid out streets’, the cottages in ‘a much better style’ than usual in the Urals and the town clean and ‘evidently under the eye of a master’. Mr Salemerskoi, the owner, lived here himself in a very large house where, being a keen horticulturist, ‘cherries, plums and peaches … [grew] in great perfection’, while his large orangery was full of lemon and orange trees, some ‘in full fruit’, despite the outside climate. The extensive greenhouses and hothouses with their differing temperatures grew ‘splendid’ flowers and tropical plants. In one, Thomas writes, were 200 species of calceolaria, almost all in flower. Thomas ‘never saw anything more gorgeous – the colours were perfectly dazzling … in all shades from the deepest purple, crimson, scarlet, and orange, to a pale yellow’. All this apart, Mr. Salemerskoi was ‘a man of good taste … [who possessed] valuable works of art’, in addition a good musician – and had some fine English horses which he bred. So much for the unsophisticated Urals countryside 150 years ago!

‘Leaning tower, Neviansk’ (Nevyansk)

After two days sketching the Syssertsky iron-works Thomas continued south to Zlataust, ‘the Birmingham and Sheffield of Eastern Russia’ as Murchison called it, during a big spring festival where the women and girls were dressed ‘as usual, in very gay colours’. Thanks to the power derived from a dam, a large blast-furnace here smelted the ore and forging mills hammered the pig-iron into steel bars. In an enormous three-storeyed workshop swords and sabres were being made, some of them etched and ornamented ‘most exquisitely’, and Thomas wrote that he had not seen in either Birmingham or Sheffield any establishment that could compare with them. This workshop had been designed, built and managed by ‘one of the most skilful and ingenious metallurgists of the age’, General Pavel Petrovich Anosov, who had been in charge of the entire operation for many years, had in the past investigated painstakingly ‘the ancient art of damascening’ swords and so on (inlaying or etching patterns into them) which had been long forgotten in Europe, and succeeded not only in ‘rescuing the long lost art from oblivion’ but reaching an unmatched peak of perfection.55

Thomas continued south over wooded, undulating country, past good fields of rye and ‘fine pastures’ for cattle, typical of the southern Urals, to the sheltered Miass river valley,56 with its birch, poplar and willow – so unlike the country further north. Here grass grew in some places up to his shoulders, providing abundant hay in winter for the cattle, and ‘every family in this region possesses horses, cows, pigs and often poultry and they always have good milk and cream’, although they did not know how to make good butter. But they certainly grew ‘every kind of vegetable’ and there was ‘plenty of wild fruit on the hills … all … delicious’: strawberries, raspberries, blackcurrants. In the mountains there was game, in the streams many grayling and in the lakes pike, so they were living in a very unusual land of plenty. For Thomas this rural economy must have come as a welcome change after all those zavods and a salutary reminder that good earth is ultimately more important in what it can provide than what lies beneath.

He had been in the Urals for two months and had travelled some 300 km along the chain, apart from his journey down the Chusovaya; it was now time to depart. Before he left Ekaterinburg finally, his friends advised him, much against his wishes, to hire a servant, stressing that he had scarcely a word of Russian and an illness or accident in a remote place was always possible. He took on a twenty-four-year-old natural son of the Urals’ chief medical officer who spoke fluent German, which Thomas knew slightly, and the authorities ‘most cheerfully’ produced the necessary papers for him. Almost nothing more is heard of this man. ‘In spite of every effort’, Thomas wrote on his departure, ‘a feeling of deep sadness crept over me when I took my last look at the high crest forming the boundary of Europe.… But the die was cast; I gave the word, “Forward!” … the horses dashed off, and we were galloping onward into Asia’ – by which he meant Siberia.

III. Western Siberia and South into the Steppe

He proceeded south-east by boat and tarantas, with his portfolio of sketches ever growing. The horses would gallop through the night, the bells attached to a wooden bow – above the central horse’s head if a troika – making a ‘tremendous clangor: sometimes … a most melancholy sound … in the dark forest of Siberia’. The forest was set on the great West Siberian Plain, through immense wetlands, a ‘place of Torment … [breeding] millions of mosquitos, apparently more blood-thirsty than any I had before encountered’.

‘View looking down upon the lake’

This was Thomas’s caption to the woodcut in his first book. Perhaps he never knew the lake’s name – Borovoye. The strange peak at the left is Okzhetpes (‘Unreachable for arrows’). A growing resort area today, Borovoye lies roughly in the centre of northern Kazakhstan, which the two Atkinsons did not visit, so this must have been on his first, solo visit.