ONE DAY IN 1849 Lucy wrote to a friend from Kopal, ‘We are now about to wander in the stupendous mountain-chains which I have been looking at for months from my windows.’ She meant the 400 km-long Dzhungarian Alatau,1 only 15 km or so from Kopal, running north-east between the Tien Shan range and the Altai, which demarcate the border with China’s far-western province of Xinjiang. They are considered by some as the northernmost spur of the great Tien Shan, with its thirty peaks above 6,000 m compared to the Dzhungarian Alatau’s highest, at 4,622 m.2

Nonetheless, the Dzhungarian Alatau have their own majestic snow-clad peaks, permafrost and glaciers, the largest 11 km long, as well as earthquakes (it is a major seismic area) which ‘often cause major rock avalanches and bring whole mountains tumbling down’.3 The Atkinsons were to witness huge amounts of fallen rock and not only mountains and Alpine meadow but, on their further travels, steppe and semi-desert. And they were to find many narrow valleys in these mountains – indeed, dramatic ravines – due to the intense erosion of the northern side of the range by swift rivers in the annual thaw of snow and ice.

It was impossible to reach the highest mountains before May, so Thomas and Lucy – and sometimes Alatau too – would meanwhile make short excursions from Kopal into the nearer and lower heights. In early May, for instance,4 the three Atkinsons made up a party to the Arasan, a warm medicinal spring in the foothills, supposedly known for 3,000 years and resorted to for many centuries not only by the Kazakhs,5 who regarded it as holy ground (according to Thomas’s journal), but by Kalmyks, Tatars and Chinese too. A yurt had been sent ahead to the furthest point horses could reach ‘with all the necessaries for a tea party’ and the group followed on horseback for some two hours along the river bank, ‘very picturesque in many parts’.6

The View from this place [Thomas’s journal records on their arrival] was exceedingly beautiful; on each side Large Masses of rock rose up to a great Hight. Between these was seen some of the High peaks of the Alatou partly covered with snow while around us the Vegetation and the Flowers were most luxuriant. The rocks at this place are yellow and purple marble [also] exceedingly beautiful.

They found the Arasan spring in a small ravine 300 or 400 feet above the river Kopal. A large bath of rough stones 23 feet long had been built here by the Kalmyks, and nearby were the foundations of a Kalmyk temple. Thomas noted that the spring, which emerged as a small jet of water, was a constant 36°C winter and summer (although Lucy claimed it ranged between 68 and 74°C) and contained much sulphur and ‘carbonic gas’ bubbling up, so that ten baths would, Thomas was told, cure scurvy and ‘eruptions’. (It is now known to be slightly radioactive.)7 They bathed the four-month-old Alatau in it – the air very cold for him as he left the warm water – and, interestingly, a roughness on his skin from birth soon disappeared.8

After the inevitable tea they started back for Kopal but had not gone far when a storm threatened and, despite riding as fast as possible, they were caught a few versts from the fort and got soaked for the umpteenth time. Soon after their return home the lightning flashed dramatically and the thunder roared, all ‘followed by a great Bouran’. And the next day was stormy, so Thomas could not go out to sketch but worked on his views of Altin-Kul, which they had visited the previous July and the pictures of which he had worked on back in December.9

Another expedition was to the picturesque spot at the foot of the Alatau after which they had called their son: Tamchiboulac, Kirgiz (i.e. Kazakh) for ‘a dropping well’. Half-way up a great convex cliff face, wrote Thomas,

The water comes trickling out of the rocks in thousands of little streams that shine like showers of diamonds; while the rocks, which are greatly varied in colour, from a bright yellow to a deep red, give to some parts the appearance of innumerable drops of liquid fire … the water drops into a large basin, which runs over fallen masses of stone in a considerable stream [and on to the Kopal river].

Large plants (unidentified) grew at the top, some hanging over in picturesque masses; Lucy found it ‘an enchanting spot’ and Thomas thought it ‘magnificent’ but regretted that the lithograph in his first book ‘gives but a faint representation of its beauty’. The large watercolour of the scene is, alas, one of his many paintings to be lost.

Another time, higher in the mountains, on the edge of a great precipice they found a ‘perpendicular face of snow, not less than a thousand feet high’. Almost perpendicular perhaps, but Lucy hastens to defend her statement: ‘As travellers are generally accused of exaggeration … [I should] tell you that nothing of the kind shall enter into the account of our journey.’10

On 12 May they began to travel in earnest with Baron Wrangel, leaving Kopal south-west along the foot of the mountains for the valley of the Karatal, one of the many rivers of Semirechye (‘Seven rivers’) which all flow north and north-west from the Dzhungarian Alatau’s parallel mountain ridges into Lake Balkhash. They had often come this way before, but this time Thomas observed ‘that the ground was now covered with beautifull yellow tulips – and some other Flowers quite new to me’.11 After four hours they reached the aul of Sultan Souk, ‘a deep old Scoundrel’, Thomas considered, but nonetheless there they spent the night.

A waterfall in the Dzhungarian Alatau (?)

Waterfalls were one of Thomas’s recurring motifs, particularly in mountain areas, and this is believed to be a scene in the Dzhungarian Alatau range in Kazakhstan, with its snow-capped mountain peaks in the distance. Once again he uses foreground rocks – often the same colour – to lead the eye into the picture.

‘Tamchi-Boulac, or dropping spring, Chinese Tartary’

At the foot of the Dzhungarian Alatau the Atkinsons found this ‘dropping spring’, and Thomas felt that his lithograph did not do it justice. The Atkinsons were so entranced that they called their son after it.

Next morning they travelled over a high table-land covered with fine grass on which thousands of cattle would soon be feeding, as the Kazakhs were leaving the steppe for the mountains. At the river Balikty, which cuts through it in a deep gorge, were a great many trees including birch and aspen but, particularly, tall poplars, and Thomas, more interested in nature than Lucy, noted a great variety of birds, ‘some with beautiful green Plumage on the Neck and Breast shaded into a brown on the Back and Tail, others with black heads a fine crimson on the neck the rest a dark grey’,12 besides very many pigeons. They passed that day a large barrow of stones some 25 feet high on which Kazakhs had placed horsetails, manes, hair, rags and other offerings as the tomb was held ‘most sacred and in great Esteem’. According to Kazakh tradition this was the grave of a mighty Kalmyk chief, ‘who ruled over his followers with so much justice that He still watches over those who inhabit his Kingdom’.13

Once Thomas had sketched the view towards the Alatau they continued their ride over undulating hills and soon came in sight of the mountains near the Karatal river. Two hours’ sharp riding brought them down to its wide river plain, where a great number of large barrows proved it had once been thickly peopled, concluded Thomas, but Lucy claimed it was the scene of numerous past battles where many huge tombs testified to perhaps hundreds of victims – a ‘matter for much speculation’, she thought. Perhaps they were chiefs’ burials? Now there were only a few Kazakhs tending their flocks. They rode on a few versts to the river Terekty, where yurts had been prepared for them, and found an invitation from a Tatar merchant to drink tea; next morning he sent Thomas a present of trout (a rare mention of fish).

On a hill to the west ‘a great lama’ had once lived, and shapeless masses of stone marked what had been his temple and dwelling. They crossed (or possibly re-crossed) the Karatal to join an old mullah (Islam had overtaken Buddhism) whom they had met in Kopal; he spoke tolerable Russian and gave them tea and fruit, treating them most hospitably. Thomas recorded in his journal:

This man possesses more influence in his Horde than the Archbishop of Canterbury in his Diocese. His Ideas of our religion are very curious. He says all our Clergy are impostors, and the doctrine they preach humbuggery – everything they do is for gain and not for the love of God – whom he says they reduce to the State of Man when they tell you He Made the World in Six days and was then so tired that he slept the seventh. He says God can create in a moment nor does it require any number of days or even hours for the Almighty to attend his labours.14

Again Lucy writes almost identically, quoting the mullah’s words that God ‘has not to work like a cobbler for ten or twelve hours a day. What would our divines say to this?’

The next morning Thomas made a sketch of the Karatal river, valley and the lama’s hill including many barrows; then they began to ride up the valley towards the mountain river Kora and two other tributaries of the Karatal, and found magnificent views on the way. They passed many auls and great numbers of Kazakhs cultivating the land for grain, some sowing (it took place twice a year) and others repairing irrigation channels which produced a crop ‘one Hundredfold and often more’.

Thomas recorded in his journal that the Kazakhs

keep breaking up fresh land that has been pastures for centuries. These people have a fine country producing everything they require with vast herds of Horses, Camels, Oxen, Cows, Sheep and Goats, all of which are pastured without one fraction of rent. They have game in abundance with wild Fruit in great variety and of excellent quality but unfortunately the Men are idle, the work having to be done by the Women … while the men visit each other and drink cumis, their favourite beverage.15 Walk they will not even for a short distance perhaps it is difficult to do so with their high heeled boots.… [He considered that their days were] spent in sleeply indolence, or planing barantes on their distant Countrymen whom they often plunder, carrying off at one time from one to Two Thousand Horses Five or six hundred Camels, and often Ten Thousand Sheep with their Women and Children, Yourts and all they possess; In these [barantes] it often happens that many are killed. After a successful robbery of this Sort they have great feasting until some stronger party commit a robbery in return.16

‘Night attack on the aoul of Mahomed’

Once the Atkinsons stayed with Mahomed, an elderly Kazakh chief, in his aul where one night a mounted band of thieves attacked to steal about 100 horses. Mahomed’s tribesmen leapt on to their own horses, battleaxes ready, the Cossacks seized their muskets and Thomas fired his rifle while the women and children panicked and the horses galloped round. All was confusion, but Lucy was determined not to miss it.

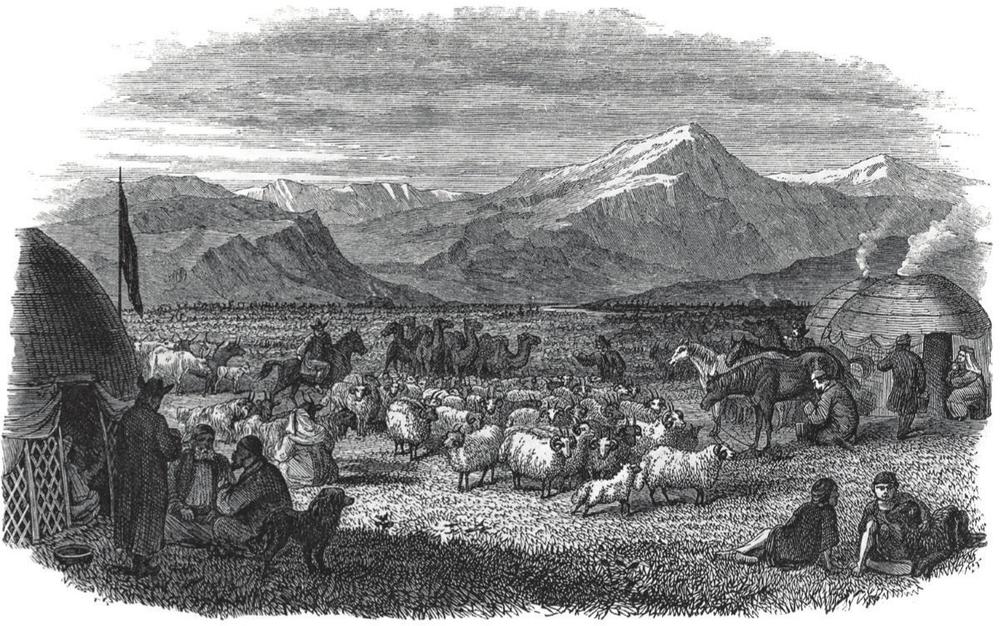

‘A Kirghiz encampment – flocks and herds returning at sunset’

They crossed the Kora and after only half an hour reached the Chadzha, where they had yurts erected in an attractive spot by the river. Thomas ‘found some excellent points to sketch where the river had cut a great gorge through a high granite mountain’, and made their way through to ‘a fine view of the snow Mountains towering many Thousand feet above’, too steep and rocky to ascend. ‘In the lower part there are many Tigers seen17 and [I] should have been glad to try my wintofka [rifle] on them.’

A beautiful morning gave Thomas the prospect of sketching in the higher mountains to which he was determined to ascend. From one summit he sketched ‘a splendid view’ of the plain and the rivers below with the mountains behind, then rode along the ridge and well above the line of perpetual snow to another fine view and a great variety of flowers including many new to him.

To the East the mountains rose in long succession, their white crests cutting against a deep blue sky, so intense that on looking up it appeared almost black. Turning to the West I had a View over the Steppe as far as the Balkash Lake which was like a plate of Polished Silver in the blue and misty distance.18

On the same day, having finished one sketch he rode for three hours to ‘a most rapid and roaring torrent … passing Rocks chiefly of slate and in some parts porphyry – Bushes and flowering shrubs grew in the small ravines while the ground [was] covered with flowers up to the Snow line, and beyond it a white crocus grew in many places’. He returned to the yurt only at 7 o’clock ‘somewhat tired after so long a ride to say nothing of being very hungry’. That evening

A cossack arrived from Omsk with dispatches for the Baron. Their contents had an extraordinary effect upon him. If I had not previously known that he was a little wrong in his upper story His conduct this evening would have shewn it. He told me he must return to Kapal in the Morning as the paper[s?] must be answerd by Saturday Post. It appears from what he said [that] the Prince [i.e. the Governor-General of Western Siberia in Omsk] had written a very severe letter during the night. He [Baron Wrangel] was raving about his [own] capability of conducting a campain [probably a diplomatic campaign] against Bokara and Tashkent without the advice of the Fools in Omsk – with many other matters on which he believes that he alone understands.19

That night there was much rain and the next morning on reaching the Kora, tributary of the Karatal, they found it very difficult to cross. Here the Baron left for Kopal and Thomas started up the river valley.20 ‘Its outlet into the plain is truly grand’, he wrote, ‘it has cut through a mighty Mountain chain – the Rocks rising up for several Thousand feet.’

I determined to go up as far as I could before sketching and then take any views I thought good on my return. We left our Horses at the mouth of the Chasm as it is impossible to ride further. Track here is none…. In other parts bushes and plants were growing in Tropical Luxuriance. A little more than a verst from the entrance was the farthest point I could reach. Here the rocks were quite perpendicular from the boiling flood … no man has ever placed his foot beyond this place, nor can this torrent ever be ascended in spring or Summer, and in Winter the Chasm is so deep in Snow … that it can never be attempted with success at that time. Thus the grand and wild scenes on this stream are ever closed to man – here the Tiger has his den undisturbed, the Bear his Lair, while the Maral and Wild Deer range the wooded parts unmolested. A very Large eagle is also found amongst these crags.21

After waiting an hour for a storm to pass, Thomas and his guides descended this gorge and he made another sketch, then they set off to the next river, the Balikty, where Wrangel had ordered a yurt for Thomas for the night. They rode hard but found the yurt only after three hours on a great mountain plateau covered with fine grass pasture for the Kazakh flocks that would soon arrive. It was then the middle of May.

‘Source of the Teric-sou, Chinese Tartary’

In the Teric-sou valley, rich in grass, Thomas found a large tribe of Kazakhs with their herds of horses, camels and cattle. He found also many tumuli, venerated by the inhabitants and testifying to a once much larger population. This was one of two watercolours bought at Christie’s by Sir Roderick Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society. He bequeathed them to his nephew, who gave them in turn to the Society; they hang there today in the Tea Room.

We arrived [a]bout 5 oclock tired and Hungry – shortly the clouds cleared off and gave me a most splendid view of the Actou [Aktau, White Mountains] which run up towards the Ilia [Ili river], the snowy peaks shining like Rubies in the Setting Sun, while all below them was blue and purple with the shades of evening creeping over the lower range. In the Foreground was my yourt with the Kazakhs cooking the sheep in a large cauldron over a wood fire while the camels and horses were lying and standing around the yourt. I could not resist sketching this scene which will ever be impressed on my memory – as well as the splendid sun-set over the steppe.22

Thomas woke the next morning to find it was raining hard and that the day would be wet and stormy. A long ride lay ahead and he wanted to make sketches of the nearby Balikty, so he started at 5 o’clock, reaching the river’s rocky gorge, but the rain forbade any sketches. Climbing back to the plateau, the Kazakhs pointed to the clouds descending fast from the mountains and the storm soon drenched them thoroughly. A ride of five hours brought them to the mountains near Kopal, where there had been no rain and ‘Another hour landed me at home. Lucy and Alatau were both delighted to see me’ (a rare and affectionate comment on wife and child).23

Two days later he was off again, sketching this time a large Kalmyk barrow or kurgan about seven versts from Kopal, one of a vast number of barrows spread across the plain. This one was ‘at least 300 feet in diameter & 30 feet high … [and] a trench all round it five feet deep and 12 feet wide. On the Top of the Barrow … [was] a circular hollow about 10 feet deep … beneath this no doubt Body or Bodies buried’ and he concluded that it had never been disturbed. On the west side he found

four Masses of large Stones standing in circles. These I suppose to have been the Altars on which the Victims have been sacrificed to the Manes [souls] of the dead. But to whom these belong or when thrown up is a matter wrapped in the deepest obscurity which will never be unravelled.24

But following many excavations in Kazakhstan these kurgans are now attributed to Sak or Saka tribes of the fifth to third centuries BC of whom Herodotus wrote, probably a branch of the Scythians, and to the later Sarmatian tribes of the first and second centuries AD. In these tombs of chiefs has been found ‘a staggering amount of golden jewellery [and ornaments], appliqués and horse trappings … in Scythian-Siberian style, including a skeleton in elaborate golden mail (“the Golden Man”)’.25 But of this the Atkinsons knew nothing and ‘a ride over this plain’, wrote Thomas, ‘Makes one feel Melancholy to look at such numbers of graves. West from the Large one there are some Hundreds. In fact Kapal is built on a city of the dead.’26

In early May Thomas made a significant note in his journal:

Fortunately we had a change in the weather this Morning Air felt soft and Mild and the snow melted fast in the Mountains. This I soon saw by the quantity of water in the Kopal [river]. I have now watched for a favourable change with great anxiety wishing to turn my back on Kopal at the earliest moment. Both Lucy and I are heartly sick of the place and people. We shall hail the day with joy when we can say adieu to all.

Surprising, perhaps, but they had been cooped up with the same handful of people all winter and indeed for eight months.27 And the next day he began to prepare for their departure. But their one great difficulty was the lack of flour: ‘without bread it was almost impossible to exist. We applied everywhere but none could be got. At last the Baron got us two poods from a Tartar, all that could be obtained’, although another pood was given them by one of the officers who could ill afford to part with it and, though not well off, would accept nothing except some candles that had been sent to Thomas and Lucy. (Before they received them Lucy noted that they ‘had been obliged to follow the example of the birds, that is to go to roost at dusk’.) They had the flour made into rusks, but certainly not enough for the three months’ journey that was to lie ahead.28

In the next fortnight of preparations Thomas’s journal is totally blank. And their last night at Kopal they chose to spend at the Arasan mineral spring once again, accompanied by Wrangel, Abakumov, ‘Madam & Mr Serabrikoff [Serebryakov], Madam & Mr Vishigin’ and, oddly, Timothy John – another Britisher? (the sole reference to these names by Thomas and never by Lucy). They cast their last look on the place with its numerous surrounding tumuli on 24 May and turned their steps to the east. Their other friends came to see them off, the men on horseback, the ladies ‘on a miserable machine which had been made purposely for their accommodation … in the form of a char-a-banc’. The usually intrepid Lucy sat with them ‘in great fear [for once], expecting every moment to be jolted off; beside which, a number of screaming women were clutching hold of me at every instant’.

The party passed the foot of one mountain sacred to the Kazakhs, atop which, traditionally, the beneficent daughter of a king had been buried. Her spirit was believed to wander abroad doing good and where she trod grass grew; certainly the summit remained green and luxuriant through the entire year, a surprising contrast in winter to the surrounding snow-clad peaks. That evening they arrived at the Arasan spring to spend the ‘lovely [moonlit] night, undisturbed by even a breath of wind’ and ‘until bed-time right merrily did the hours roll on’ in ‘dancing, singing, bathing, &c.’ When ‘a Cossack began playing on his balalaika … quickly dispelling the gloom all had felt [at the parting] … in a few minutes we were dancing Cossack dances on the turf to his wild music’. Chinese brandy from Kuldzha enlivened the occasion further, ‘and no ball given in polite society ever passed off with more true enjoyment’. Surprisingly, Lucy says, none of the party had brought anything for the night other than ‘night caps; neither combs, brushes, nor towels’ (this last a particularly strange omission in view of the bathing).

Next morning the Atkinsons said goodbye to all their friends except Abakumov, who rode with them until they began to descend a pass to the steppe. Their Cossack Pavil (Pavel), of about twenty, who had been their faithful attendant for so many months,

really sobbed again as he kissed Alatau for the last time. Poor fellow! – he had become quite attached to the child, having, I might almost say, nursed him from his birth, taking far more care of him than any woman would have done; and, besides, they were excellent friends.… Often has he stood by me, talking of his home and his mother whom he had left, and how much he wished to see her. He appeared pleased to find one who was a willing listener to his tales of home…. We, too, felt sorrow on bidding farewell to Pavil.

Now setting off [once more almost certainly with a Cossack guide] I shall not fail in my promise of giving you29 an account of any little incident that may take place, that is, if I am not made prisoner by some of the tribes we may meet with. I may be taken for a Kazakh, stolen from some distant aoul and disguised in, I will not say European, but an unknown costume. I look as scraggy and almost as haggard as any of their own beauties; I am nothing but skin and bone: scarcely a pound of flesh left on me, nor is my husband one whit better.

The three Atkinsons now began a wandering lifestyle (often in bad weather), staying with Kazakhs and sometimes travelling with them, impressed by their vast herds of cattle – and struck by seeing sheep with four horns, evidently quite common. Climbing one pass to the higher mountain ranges, they were enveloped in such thick fog that they could not see even ten paces ahead and, soaked to the skin, were led safely to an aul only by the barking of dogs. The fog had compelled Kazakhs to pitch camp there on the way to their high summer pastures: an unsuitable place, for next morning the Atkinsons found they were close to the brink of a precipice with the steppe 5,000 feet below. ‘It was like a map,’ wrote Lucy, copying Thomas’s journal entry exactly; ‘we saw the rivers Sarcand, Bascan, and Acsou [Aksu, meaning White Water] … shining like threads of silver until they were lost in the haze towards the [lake] Balkhash [nearly 100 miles to the north]. The higher summits near us were still capped in the clouds.’

Thomas noted that ‘The Plants and Flowers have a Tropical growth; when you ride amongst them you find they are far above your head.’ Lucy picked many of the yellow roses that grew here en masse and pressed them with great care, but all were spoiled in crossing the rivers. There was also a large, yellow, sweet-scented poppy, a peony, acres of dense cowslips, a mass of pink primroses and many other flowers – besides flowering shrubs ‘of every colour: how I envied my husband his knowledge of botany’ (although Thomas’s journal, from which she copies that list, admitted to ‘a great variety of other Flowers’ that he did not know). Lucy continues, ‘I was only able to admire, and I did admire, the surrounding beauty, and almost envied those who dwelt in such lovely places.’ Wild fruit, too, grew here in profusion: peaches, strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, black and red currants, apples and other fruits that Lucy did not know. Yet, they found, the Kazakhs never ate them. ‘Vegetables and fruit are for birds and beasts; they are made for the animals’, one explained to Thomas, ‘and the animals for men’.

Nearing the summit of one pass dense clouds thoroughly drenched them, but they found an aul with snow just below it so ‘got water for Tea. Had a good fire made and passed a tolerable night’. Next morning they ‘Turned out early’ as usual, ‘found the grass frozen’ (this in June) and began a difficult descent into one valley, the cloud-covered summits above them. After four and a half hours they ‘came upon a most frightfull chasm in which [the] River Terekta runs near the Brink…. It was no easy matter – even to walk down.’

They were particularly impressed by the sight from one mountainside, wrote Thomas:

Looking over the step … there was seen a long line of Kazakhs with their Camels, Horses, Oxen, sheep and their yourts. On reaching the Pass we soon found it was filled with Kazakhs and their Flocks all marching towards their summer quarters in the Alatou mountains. We First came upon a flock of sheep several of which had four horns [which he was told were numerous]…. All together this was the most interesting scene there [were] Hundreds of camels … in line loaded with the household goods. We could not have passed less than a Thousand or 1,200. Oxen and cows … [with] many Women and children on their backs [and on one camel’s back was] the chair of state [probably a ceremonial chair used by the head of a particular horde or tribal union] adorned with Peacocks feathers. There were also many Thousands of Horses loose as well as … [a] great multitude of sheep and Lambs giving us an idea of the march of the Jews. Thus the people are a wild looking race more like roving Bandits than peacable men.30

Riding ever north-east, they came to the long canyon of the ‘small but turbulent’31 Aksu river and rode up it as far as the horses could go: a place of more perpendicular rocks and a roaring torrent with large trees snapped asunder in their passage downriver. It was fearful to stand and contemplate such places, thought Lucy. They reached the next river, the Sarkand, on 2 June and pitched their tent, intending to cross the next morning. But the bridge the Kazakhs had constructed consisted only of a few trees laid across the river from a rock near its centre, and the Atkinsons feared that the water, which was rising, could sweep it away overnight, so Thomas resolved to proceed at once. Did Lucy object, thinking of her own or her child’s safety? We do not know, but it is surely unlikely, bearing in mind that Thomas was always very much in command and took the decisions (‘I ordred’ is a very common phrase in his journal) and Lucy certainly had a determined and adventurous streak. She wrote mildly,

The crossing [that followed] was not agreeable, seeing the raging torrent under our horses’ feet. One false step and all would have been finished. The noise of the stones being brought down, and the roar of the torrent, was so deafening, that we were obliged to go close up to each other to hear a word that was spoken. At last it became really painful; the head appeared full to bursting. I walked away some distance to try to get a little relief, but it was useless; a verst from the river the roar was still painfully heard. This din, coupled with the thunder, was awful … fearfully grand, there being a short heavy growl in the distance, as if the spirits of the storm were crushing huge mountains together, and grinding them to powder; and the lightning descended in thick streams.

After six days in the Sarkand area they started for the Baskan, the next river east. Nearing it they were greeted by yet another violent thunderstorm which had evidently scared a fawn (a young maral),32 so much that it had descended from the higher mountains and came near the Kazakh yurts. The Kazakhs immediately gave chase with much shouting, and the Cossacks galloped after them up the Baskan gorge. They soon returned with the maral alive and uninjured and presented ‘the beautiful creature’, a female, to Lucy. Once Alatau was in bed, she went into the Cossacks’ tent to see the captive. They were trying to feed her on milk but she would not take it. When Lucy caressed her she tried to take some but could not, so Lucy asked the Cossacks to free her as being too young to be taken from her mother. They would do so, they said, when they had caught the mother; she would come down in the night and start crying for her infant, and they would soon catch her as she would never leave as long as she knew her young was there and would be sure to answer. Lucy’s heart ‘bled for the mother’; she was one herself, and she felt there was nothing the mother would not do for the sake of her young; and what indeed would the fawn do without her? She begged the Cossacks again to set the animal free, which they agreed to do once the storm was over – and meanwhile the mother might be caught.

Lucy found some light blue ribbons which she tied round the young maral’s neck, much to the amusement of the Kazakhs: ‘the colour contrasted beautifully with her coat’. As she did so, the animal raised her large soft eyes so piteously to Lucy’s face that Lucy embraced her and at the same time loosened the rope with which she was tied. Hardly had Lucy left the tent when she heard shouts and saw to her delight the graceful animal bounding up the mountainside. Cossacks and Kazakhs rode off in pursuit but failed to capture her again, and high up the mountainside the mother’s voice could be heard calling to her young. Months later, Lucy had cause to rejoice, for she learned that her little beribboned protégée was taken for a sacred animal. Though many Kazakhs had seen her both with her mother and later without her, they forbore shooting her, and ‘the tale of the sacred animal was always related with great gravity. When told by the Cossacks that I had tied the ribbon round her, they would not believe it, declaring she had been born so.’

When on the Baskan river Lucy was given a second maral deer. This one had been caught when young and was completely tame. ‘I used to leave him at times with the different tribes we met with, and take him up on our return from the rambles; sometimes he trotted by us, and at others his feet were tied together, and he was seated before one of the men. He was a beautiful creature, with large expressive eyes.’ Lucy was much attached to Bascan, as they called him (with their usual wayward spelling), and thought his love for Alatau remarkable. If in the evening Thomas took Alatau in his arms when they were setting up camp and Lucy was busy with domestic matters, Bascan always followed Alatau. Thomas told Lucy that Bascan’s apparent affection was due to her lively imagination and, putting Alatau down, said, ‘Now see, Bascan will follow me.’ But Bascan never moved and lay down with Alatau. Thomas took up the child again and immediately Bascan followed, but this had to be repeated several times before Thomas was convinced.

Bascan also disdained any yurt other than the Atkinsons’. One evening Thomas had gone for a stroll and Lucy was doing some sewing, sitting on the grass outside their yurt to prevent Bascan entering as Alatau was in bed (oddly, Lucy once again calls him ‘the boy’ rather than ‘Alatau’). But Bascan was not to be put off and Lucy had to jump up every few minutes to stop him. She therefore found some rope and tied it zigzag across the doorway as high as she could reach. This halted Bascan for the moment, but he kept wandering round the yurt and each time he neared the door he checked his speed and cast longing glances at it. Suddenly he took a leap and cleared the ropes. Lucy was instantly on her feet and darted into the tent to thrust him out when she saw a sight that arrested her attention.

The creature had bounded to the child, and lying down gracefully beside him, was reclining his chin on the bed, close to the little fellow’s face. My heart would not allow me to touch him, he seemed to watch over him as though he wished to protect the boy, so I left him in peace, innocence beside innocence; after this Bascan was a privileged creature, coming in and going out at pleasure – but, alas, for poor Bascan, his fate was a sad one. [He died of heat-stroke.]

Thomas’s flute, which the Kalmyks had much admired in the Altai, was admired by the Kazakhs too. One of the sultans with whom the Atkinsons had been staying on their journey had been so struck by it that he travelled for two days with a few of his followers to hear it played once more and then asked permission to play it himself. After many attempts he handed it back, saying he would have nothing more to do with it: it was Shaitan and Thomas must have had dealings with him, otherwise why did the flute not answer him when he whispered to it? Thomas played on it again and once more offered it to the sultan but now he absolutely declined to touch it.

Far up in the mountains the Atkinsons came across many Kazakhs (probably moving to their summer pastures) whom they had met earlier on their original journey south into the steppe. All were delighted to see the foreigners again and particularly pleased to meet Alatau, now seven months old. Lucy reflected:

How lucky it is that he is a boy, and not a girl; the latter are most insignificant articles of barter. I am scarcely ever looked at excepting by the poor women, but the boy is somebody. The sultans wished to keep him: they declared he belonged to them; he was born in their territories, had been fed by their sheep and wild animals, ridden their horses, and had received their name; therefore he belonged to them, and ought to be left in their country to become a great chief. The presents the child received whilst amongst them were marvellous: pieces of silk (which, by the way, I mean to appropriate to myself), pieces of Bokharian material for dressing gowns, lambs [Lucy’s italics] without end, goats to ride upon, and on which they seat him and trot him round the yourts; one woman holding him, whilst another led the animal. And one sultan said, if I would leave him, he would give him a stud of horses and attendants; but I have vanity enough to suppose my child is destined to act a nobler rôle on this world’s stage than the planning of Barantas, or living more like a beast than a man, and passing his days in sleepy indolence. Still he is to be envied, lucky boy! Why was I not born a boy instead of a girl? – still, had it been so, I should not have been the fortunate mortal I am now – that is, the wife of my husband and the mother of my boy.

Some of the tribes the travellers came across had never seen a European woman; and, Lucy continued,

these believed I was not a woman, and that, I being a man, we were curiosities of nature; that Allah was to be praised for his wonderful works – two men to have a baby! One of our Cossacks I thought would have dropped from his horse with laughter. I was obliged to doff my hat, unfasten my hair, and let it stream around me, to try and convince them; but this did not at first satisfy them, still I believe at last I left them under a conviction that I was not the wonderful being they had first imagined me to be.

One day a Kazakh woman took Lucy to see her baby of only a month old but so big that Lucy thought it must be a year old. Kazakh babies, she found, were strapped to boards naked but wrapped in fur until old enough to crawl and never washed from the hour of birth (unless drenched with rain) until old enough to run into a stream and take care of themselves. Lucy learned that when a birth was imminent, the mother was thought to be possessed by the devil and was lightly struck with sticks to drive him away. As the moment approached, they would call on the evil spirit to leave her.

Poor woman! Her lot in a future existence, it is to be hoped, will be an easier one, as here she is a true slave to man, contributing to his pleasure in every way, supplying all his wants, attending to his cattle, saddling his horse, fixing the tents, and I have seen the women helping these ‘lords of creation’ into the saddle.

Thomas mischievously told Lucy that the Kazakhs had opened his eyes to what was due to husbands and that he was half inclined to profit from the lesson. He even thought of starting an institution to teach husbands how to manage their wives which he thought would be profitable and was ‘much required in England’. Lucy lamented that the Kazakhs considered even a dog superior to a woman; when a favourite dog was about to have pups, carpets and cushions were given her to lie on and she was stroked, caressed and fed upon the very best. ‘Women alone must toil, and they do so very patiently.’ Once a Kazakh man, seeing Lucy busy sewing, making a coat for her husband, became so captivated by her fingers ‘that he asked Mr Atkinson whether he would be willing to sell me; he decidedly did not know the animal, or he would not have attempted to make the bargain. With me amongst them, there would shortly have been a rebellion in camp.’

On one occasion Thomas was suddenly taken ill after sketching for a long time in the sun. The Cossacks, ‘really good creatures’, were greatly concerned, dug a hole in the ground, placed stones over it and wood beneath which they lit so the stones became red-hot, then covered the lot with a low voilok, and crept in beneath to throw cold water over the stones, ‘making a tremendous steam’. Thomas made a small drawing in his journal. He was laid in this and given ‘a proper stewing … for which he felt all the better, walking back quite briskly’. She and Alatau, however, kept in perfect health on their travels by ‘constant bathing in cold water; the ice had often and often to be broken [in winter] to allow us to plunge in’, but it did not suit Thomas.

Lucy did not think that she ever saw anything more picturesque or pastoral than the Kazakhs with their cattle in what they called a granite crater ‘like an immense portal’: the sheep and goats wandering together as always: to hear the tinkling of the goat bells ‘in the silence of this marvellous spot was striking’ just as it was to watch the goats ascend the precipices, seeming to bound and leap from crag to rock and ‘almost like flies … cling to the face of them’. Above them on what appeared to be the summit nearly fifty gazelles stood quietly looking down on the humans far below, knowing they were safe at that distance from any gun. After some ten minutes they ‘scampered off like lightning’, disturbed by an enormous wild sheep with ‘splendid curled horns;33 a grand fellow to look at’.

At the crater the Atkinsons saw a magnificent sunset over the steppe ‘spread out like a map, the rivers looking like threads of silver, while towards the great Lake Balkhash lay a boundless, dreary waste’ and in the sky shone golden tints. ‘Those who have not visited these regions can form no conception of the splendour of an evening scene over the steppe,’ wrote Lucy.

Leaving one Cossack behind with the baggage, they took the other two with them together with a night or so’s necessities, climbed the mountain – very difficult for the horses and camels – and on their ascent came across ‘huge piles of granite, all piled up in confusion … like the remains of some gigantic statues … [or] the ruins of some mighty city’. At last they reached the summit, and saw towering above them the Aktau, formed from white gypsum crystals,34 their ‘peaks shining like burnished silver’. Here they spent the night in a yurt as a violent thunderstorm erupted with rain and hail, and next morning they found (in early June) that six inches of snow had fallen. At breakfast a Cossack told them that a camel had just fallen on to rocks and had been killed outright, ‘an event which reconciled us to some delay’. Later in the day, while eating a hasty dinner in order to leave the brink of a ‘fearsome gulf’, they heard the sound of wailing: a man had just brought the news that eight horses had fallen down the mountain to their deaths, three of them mares in foal. ‘It was quite painful’, wrote Lucy, ‘to listen to these poor creatures, to whom one was unable to offer even the slightest comfort. We now determined to await the morrow, fearing to meet with a like disaster.’

‘Argali’

Fortunately, the next morning was bright and sunny, giving them hopes of leaving their ‘rocky prison’. The Kazakhs now recommended placing their baggage on ‘bulls’ (i.e. oxen) rather than camels for the precarious descent, and while they and a Cossack were getting this done, the three Atkinsons set off on horseback to the spot from which they had first seen a verdigris-coloured lake far below. They had first to ascend slowly up slippery rocks and only then descend, but this proved impossible on horseback, so they continued on foot, Thomas taking Alatau and the Cossack helping Lucy. In a couple of hours they reached a small plateau where they were astonished to find about eight yurts, previously hidden from view – astonished, as everyone had told them this mountainside was impossible to descend, but, wrote Lucy, ‘my husband does not permit impossibilities, without proving them to be so himself’: a fitting motto for Thomas Witlam Atkinson.

They were greeted as usual with the barking of dogs and Lucy, innocently, found it a ‘most enchanting spot, – a perfect little Paradise’. She was in ecstasies and, taking Alatau with her, sat down recklessly on the edge of a precipice. ‘It was a fearful sight to cast the eye below. The head seemed to grow giddy, and the heart throbbed quickly, at the frightful depth; where I was sitting, it was as near perpendicular down to the [verdigris] lake.’ After standing for some time contemplating the scene, Thomas put his gun down by Lucy and walked off to choose a place for their yurt. Lucy continued to gaze in wonder at the sublimity of the prospect, finer than anything she had ever seen, she considered.

At length, turning to see why Thomas was taking so long, she was ‘fearfully startled’: their Cossack was surrounded by several Kazakh men with yurt poles, broken at their leader’s command ‘to knock our brains out with’, Thomas was hastening to the Cossack’s aid, other Kazakhs were seizing further poles to join in, and their womenfolk, arms moving wildly, were hurrying to the scene. But not a sound reached Lucy; she was too far away and all noise was drowned by a waterfall. Her heart beat rapidly and she concentrated hard on what to do as she knew Thomas and their Cossack had only their whips to defend themselves.

At first I thought of putting the child down, and running with the gun, and then I reflected he might roll over the brink before my return. If I took him with me, and the Kazakhs saw me first, they might rush forward and seize the weapon; as with the two in my arms I should have no chance of outstripping my foes, although alone I should soon have done so. In this dilemma, I concluded it would be safer to trust in Providence, and sit perfectly still.

Lucy watched the men brandishing their sticks while Thomas and the Cossack slowly retreated, facing their foes, who – especially the women – were following ‘like demons’. At that moment the Atkinsons’ other Cossack, who had been left with the bulls, appeared round a mass of rock above and, looking below, saw what was happening. ‘Without a moment’s hesitation, he rode straight down; how he was not dashed to pieces, is to me at this moment [years later] marvelous.’ As soon as the Kazakhs saw him start to descend, they closed round Thomas and the first Cossack. The latter struggled both with the attackers’ leader and a woman clinging on to him from behind but, being small, he could not extricate himself from her grasp so managed to give her a tremendous blow which knocked her down, and two of her number carried her off. Meanwhile two men had seized Thomas and tried to pinion his arms behind him but ‘they scarcely knew what a powerful man they had to deal with’ and he quickly flung them off.

Just at that moment the second Cossack arrived on the scene with Thomas’s rifle on his shoulder. He pointed it at the enemy to no effect, but the Atkinsons’ Kazakh, leading the horses down, appeared at this point and Thomas backed towards his horse, quickly removed his pistols from their holsters and cocked and pointed them. Faced with four muzzles, their attackers dropped their poles ‘and doffed their caps in submission’. Seeing that her small party were now ‘masters of the field’, Lucy picked up Alatau and hastened to the scene of battle with a double-barrelled gun.

What a sight was there! On approaching, I heard the howling of the women, and on getting nearer I saw several with blood on their faces. Our little Cossack was pale, and breathless with the exertions he had used; blood was on his face, and his clothes were torn; but both he and the Kazakh had hold of, and had managed to bind with thongs, the leader, who proved to be master of the aoul. A more horrible sight I never witnessed; the man was actually foaming from the mouth. I could scarcely endure to look at him.

The Kazakh women brought him water but the two Cossacks would not let them approach, so Lucy benevolently gave him the water and learned what had happened. The ringleader, ‘a very bad fellow’, had taken possession of this place and, determined that no one should approach, had called his people together, urging them to kill the strangers, throw them into the lake far below – nobody would know what had become of them – and take their arms and possessions.

The ringleader ‘now became penitent, and promised not to interfere with us’. Thomas ordered that he be unbound, but the Cossacks were most reluctant, saying he was a mad robber and would make another attempt on their lives. Thomas insisted, however, and when the visitors had retired to their yurt they saw him with several of his followers seated on a rock at the edge of the precipice, haranguing them loudly and continually pointing down to the lake. One of the Cossacks told the Atkinsons that the man was still bent on mischief, urging his men to kill the intruders.

Lucy urged a quick departure, but while they were drinking tea, their ‘discourteous host’ entered the yurt and sat down. Surprisingly the Cossacks had already offered him tea which he had declined. Lucy now also offered him tea which again he refused, looking round at the Atkinsons’ possessions and starting to finger them; ‘the guns and pistols especially had charms for him’, and much to the surprise of Lucy and their Cossack, Thomas allowed him to handle them.

Unperturbed, Thomas prepared his sketching materials in order to descend to the lake and asked their antagonist for two men from his aul to accompany him. This was readily agreed but Lucy insisted on him taking a Cossack as well. However, ‘no persuasions of mine could induce him to do so’ – Thomas was always in charge – and he left ‘our own Kazakhs’ to guard Lucy and Alatau, agreeing at least to keep his guides in front of him on his way down to the lake.

The descent began and Lucy watched from the edge of the precipice until she could no longer distinguish them, then looked through her opera-glasses. (Perhaps she had used them in St Petersburg.) The master of the aul, observing her, began making signs which she could not understand and approached her. She rose from her seat and, determined to show no fear, ‘stood perfectly still, merely placing my hand in my pocket and grasping my pistol’. Lucy was suspicious of one of the Kazakhs going back and forth to the chief yurt, and then a Kazakh woman tried to persuade Lucy to go there too which she stoutly refused to do, believing that she and Alatau would be made prisoners.

However, the master of the aul gestured for the opera-glasses which obviously intrigued him. Lucy handed them to him and he returned to his rock and soon seemed thunderstruck looking at the distant travellers, then looked with the naked eye and again with the glasses, ‘his face all this time undergoing a variety of changes which it was amusing to see’. He then passed them to his followers, who all looked though them, each steadily more amazed. At last he returned them to Lucy, saying many times ‘Yak-she’ (good).

Lucy could no longer see her husband through the opera-glasses but only the horses, no bigger than ants, and even then could distinguish them solely because they were moving. Then she lost sight of them altogether as they descended even lower. Amid this dramatic mountain scenery she ‘seemed to conceive a more vivid idea of the power and presence of the Deity’ and felt that the Creator ‘did not neglect to watch and guard even the least of His creatures.… What care had been bestowed upon us this very day! We had been three opposed to upward of twenty, besides women, and my heart swelled with gratitude for our deliverance.’

Lucy’s reflections, however, were disturbed when she noticed the men leaving the rock for the Atkinsons’ yurt, and soon a woman, perhaps a wife of the ‘host’, advanced towards her. Lucy grasped her pistol, but the woman brought with her a Chinese silk handkerchief with mother-of-pearl decoration which she presented to Alatau. After the woman had gone, Lucy sent one of the Cossacks with Alatau’s red hat, which she had made in Kopal, as a present for one of the Kazakh children; it gave enormous pleasure. (Alatau now had a felt hat which Lucy had bought from a Tatar, far more useful, but certainly not as fine.)

It was nearly dusk when Thomas returned (perhaps too unconcerned), and their host (for so indeed he now proved to be) had had a sheep killed so that, after the previous conflict, all could ‘make merry’. The man who had intended that the Atkinsons should be his victims went forward to meet Thomas and shook both his hands. He entered their yurt, accepted Lucy’s offer of a glass of tea and ‘hardly knew how to be friendly enough’. Nonetheless, the Atkinsons took precautions in case of a night attack, and Lucy placed matches and her last piece of tallow candle by her side. Woken in the night by a noise, she was sure someone was in the yurt. She sat up and listened, heard their sentinel walking to and fro outside and supposed it was her imagination. Still, she determined to strike a light, but her candle had gone. She was now startled in earnest. Someone had certainly entered. She got up and looked for her one small piece of stearin (the chief ingredient of tallow) and then lay down with it and the matches in her hand, but in the morning, with no further incidents, she and Thomas laughed heartily as they realised it must have been the hungry dogs that had slipped in during the night and stolen the candle, and the disturbed voilok proved it.

On their departure that day their former would-be murderer accompanied them some way to (ironically) ensure a safe route, and ‘as the sun was setting’ they ‘arrived at a lovely spot on the granite mountain’ where a small stream ran between grassy banks and under more great blocks of fallen rock. Seven days after leaving one of their Cossacks on the Lepsy to look after their baggage, they returned and found him greatly relieved, as he had begun to fear for their safety.

They now began to descend to the steppe and all along the Lepsy’s banks found Kazakhs encamped, gradually returning at the beginning of July from the mountains. Many were old acquaintances, and there were numerous invitations to stop and feast. But after the usual salutations the travellers felt they must continue on their way. One old friend they had often met at Kopal was Sultan Boulania, one of the leading Kazakhs of the steppe; with him, however, they felt compelled to dismount and take tea. He told them it would now (2 July) be unbearable on the steppe, but they had made up their minds to go.

However, their progress down to the plain was often steep and difficult. ‘The heat became greater at every step, and then there were millions of mosquitoes, who bit us without mercy; and where we stopped, we had to fill the yourt with smoke, to drive out the enemy.’ As they proceeded, they got glimpses of the country below, which resembled a sea of yellow sand (it was probably the Saryesk-Atyrau desert) with a stripe of green along the banks of the Lepsy winding away to the horizon.

Entering one of the ravines on their descent, they found, was like going into an oven. The blast of hot air was fearful, but it was even worse on reaching the plain. ‘The sun, and the heat reflected from the arid rocks, positively boiled us,’ wrote Lucy. The temperature, she said, ranged between 69 and 75°C.35 ‘While the yurt was being fixed my husband laid his gun on the sand, but when he went to pick it up, it burnt his hand, and the blister remained for several days.’ On going into the yurt Lucy thought she would be suffocated, and to add to their discomfort they were forced to have a fire to keep off the mosquitoes. Having water poured over the sand, however, cooled the atmosphere a little. But, she went on,

Poor Alatau was in a sad state; he was one mass of bites. No one could have recognised him. I was not much better. I placed the little fellow in bed, perfectly naked, and covered [him] with a piece of muslin, which we contrived to prop up but still the brutes succeeded in getting in.

Lucy was delighted, however, by their ride along the valley of the Lepsy. The easternmost of the river’s branches meandered so peacefully through fine woods and a whole carpet of flowers, producing such a contrast to their previous dramatic scenery, that they named it ‘the Happy Valley’. And high above them the Aktau’s ‘white crests rose far into the clear blue sky’. Three days later, when Thomas had finished his tasks (presumably sketches), they rose well before dawn for their return to the mountains. Lucy had a dip in the Lepsy despite the dark and the rain – and from its banks witnessed the dawn, ‘a most lovely sight’, the first time she had seen it over the steppe. For a few moments she thought it was a fire and that the rosy tints were caused by flames. Willingly she would have stayed to watch, she wrote, but there was no time to be lost as they had to be on their way by sunrise, it being quite impossible to travel in the intense heat of the day.

It is a wonder that Alatau, still only a baby, survived all these circumstances, but his parents did all they could for him. At each small stream they dismounted, took off his ‘little dress’ and poured water over him from a cup. It took only a few minutes and his parents had the satisfaction of knowing he was refreshed ‘at the cost of a short gallop over the burning waste’, as Lucy put it. And whenever they started early, Lucy would always let Alatau rest until the yurt was about to be dismantled, and then

I aroused the little sleeper, to bathe, dress, and feed him. His toilette was soon completed, as it consisted of nothing more than one loose dress which I had made from some Bokharian material. This he wore with a belt round his waist. He never had shoes or stockings on his feet till [their return to Barnaul] … even now [writing from Barnaul later] I have difficulty in getting him to wear them. I very often find them on my table. He takes them off, and runs about without them; but this is quite common amongst Russian children and is considered very healthy … grown-up persons do the same, and delightful, I can tell you, it is, especially on the sand.

One day, while still travelling among the Kazakhs, they had an intimation of ‘civilised’ society and an invitation to it: ‘If Mr and Madame would be so good as to dine with me in the first hour, I will beg of them to bring a pair of silver spoons and a pair of forks, and nothing more will be wanting’ (Lucy’s italics). The Atkinsons found the idea ‘too delicious to refuse’, but whether they actually possessed silver spoons and forks, let alone travelled with them, we do not know. Their host-to-be on this occasion, Philonka, was a Russian merchant whom they had met both in Kopal and on the mountains. He had sent the Kazakh to find them and take them to his aul in a fine spot near the river Tentek (‘wild’ or ‘savage’). There he had prepared for them a very pleasant little yurt, ‘fitted up exquisitely’. The voilok was raised slightly all round so that a gentle breeze passed through on a sultry day. Their host’s Kazakh wife and children came to make them tea, ‘undoubtedly the best we had ever tasted’, and brought Lucy cushions on which to repose until dinner.

A sumptuous one awaited them, but no details are given. Before leaving, their host presented Alatau with a tiny drinking bowl (he had sent him an even smaller one when a week old), and Lucy called at his yurt to say goodbye to his wife.

After sitting with her for a while, she took me to a compartment separated by curtains, in which was their only son. He made me shudder to look at him. The child was about eight or ten years of age; his disease was the ‘king’s evil’36 which I was told made frightful ravages among these people; his head was swollen to a dreadful size, and in an awful state. The father entered; we spoke of the little fellow, and he said, if we could only cure the child, he would give us half his flocks. I was glad to get away – it was too painful to look upon; and for two years he had been in this state.

One of the Atkinsons’ Cossacks, whom they called Columbus, had a particularly enquiring mind. When they camped for the night or Thomas was sketching, he would squat down beside Lucy with questions. The first was always ‘Have you seen the Emperor?’ (Perhaps he did not want to take no for an answer.) He wanted to learn about England and its army, was particularly interested in geography and, after Lucy had shown him different countries on maps, borrowed them to show them to his companions, only to return with more questions after evident discussions. One day he said to Lucy, ‘I hope I do not trouble you by putting so many questions.’ She replied that she was very pleased to answer any that she could. She quotes his reply: ‘“Ah!” said he, “it is very different with you from what it is with our gentlefolks; whenever we put a question to them, they are sure to cheat us in their answers, so we never ask now for information. I am so much obliged to you for all you have taught me; in two years I am going home, and I shall have so many things to tell them.”’

Riding on to Lake Alakol (or Ala Kul, meaning ‘White Lake’), east of Balkhash and once part of that great lake,37 the lower they descended the more intense became the heat. Lucy wore no petticoat but even her cotton dress was too much for her. Contrarily, the hotter the day the more clothing the Kazakhs would wear, keeping out the greatest heat with long shubas. Thomas could not wear gloves while sketching, so the backs of his hands were soon badly blistered by the intense sun. And despite the Atkinsons’ hats, their faces became ‘a nice mahogany colour’.

One evening they reached a Kazakh aul at sunset and heard much sobbing but were too occupied to pay any attention. The next morning the sounds resumed, only more protracted. They turned out to be prayers for the dead being chanted in a yurt, outside which stood a long pole with a piece of black silk at the top, denoting death.38 Lucy was assured it would not be untoward to enter, and found inside two women, the wives of the deceased, kneeling before a pile of baggage, saddles and other items, moving their bodies to and fro and chanting together. It was evidently verse, and at the end of each verse they would bend forward, stop and sigh deeply. Lucy found they kept time extremely well and ‘the notes were so exceedingly musical, and so expressive of sorrow, that the tears flowed from my eyes. It made me so sad that my husband would not allow me to stay.’ She learned that, although the deceased had been dead for some months, it was the custom to offer up prayers for an hour at sunrise and sunset for a whole year.

It is really to Lucy rather than Thomas that we owe so much information about the Kazakhs in the mid-nineteenth century.39 He was far more concerned with the topography and their actual travels, although Kazakh customs intrigued them both, particularly her, not least the practice of breast-feeding boys till the age of ten or even eleven. Another curious custom Lucy describes was for a sultan to place pieces of meat in the mouth of a favourite follower, who would stand with his hands behind his back. Sometimes the pieces were so large ‘that a man has been known to die’ but to let them fall from the mouth or touch them with the hands would have been an act of such rudeness that apparently the favourite preferred to choke instead. Once Lucy saw a Kazakh given a whole ball of meat: ‘How the mouth got stretched to the size was inconceivable, and I verily believed the poor creature would expire, but he did not.’ She was astonished also to find that the Kazakhs could go without food for two or even three days and then eat an enormous amount, and was actually told that a man could eat a whole sheep; ‘one of them offered to treat me with the sight if I would pay for it, but I declined witnessing the disgusting feat’.

Travelling on to Lake Alakol, they rode in a storm down a rugged and gloomy pass with frowning masses high above them and the lake on its plain far below. Halfway down, the wind rushed through the ravine with such fury that they were really afraid of being blown over. All quickly dismounted and crouched down by the side of their horses, which tottered about. Despite so many burans, never had Thomas or Lucy encountered such a wind, and she wrote, ‘Had the men not seized hold of my dress, I should doubtless have been blown away; I had no more power than if I had been a leaf.’

Lucy was not exaggerating. She must have been referring to the ibe, a notoriously fierce and frequent winter wind that can reach hurricane force and last several days. It roars from the east, funnelled through the 46-mile-long Dzhungarian Gates on China’s border, some six miles wide at the narrowest, connecting the Kazakh steppe and Xinjiang between two spurs of the Alatau range. Through these historically important ‘gates’ came nomadic peoples from the east to settle, and indeed through them in the thirteenth century came the all-conquering hordes of Genghis Khan. A rift valley, it has been called ‘the one and only gateway in the mountain-wall which stretches from Manchuria to Afghanistan, over a distance of three thousand miles’.40 However, finding that the foot of the ravine they were descending was blocked with fallen rocks (earthquakes again, perhaps), the Atkinsons were compelled to climb again and ride along a very difficult ridge before a five-hour descent. Then they were once more on the steppe, travelling at the foot of the mountains on sand so that the heat was really intense and, wrote Lucy, ‘To tell you all I suffered from the heat is impossible. Suffice that at times I thought the poor horses would sink’, and their dogs (to whom there are very few references apart from Lucy’s engaging description of their behaviour) were howling piteously.

They pitched their tent at the foot of the mountains opposite Lake Alakol – even though dwarfed by Balkhash it is still 104 km long and 54 km wide, too far to see to the other side – and ordered a watch to be kept during the night as they knew that escaped convicts from a Chinese penal settlement were nearby. As the Atkinsons’ escort had no tent and the night was stormy, they kept their arms dry in the Atkinsons’ yurt. In the middle of the night Lucy woke to hear footsteps in their tent and gently woke Thomas to whisper to him. The intruder turned out to be Columbus, their Cossack escort. When Lucy asked him what he wanted, he said, ‘Our arms. There are people about.’ The Atkinsons jumped up at once. The admirable Lucy always put everything at night where she could lay her hands on it instantly.

Placing my husband’s pistols and gun into his hands, he started, bidding me lie down and keep quiet, but such was not my nature. If we were to be captured I was determined to see how it was managed, so put on my dressing gown and slippers, and out I went, with my single pistol in my hand; the other had been stolen. It appeared there were about six or eight men; they had come within fifty yards of our tent, but, observing the sentinels, had retreated across a little glen, and rode under the dark shade of a small mountain in front of us.

Thomas and the Cossack and Kazakh escort mounted their horses in pursuit, but the intruders had gone. What had seemed a vast and level plain proved to be undulating and intersected with gullies where riders could easily hide. If the miscreants had stolen the party’s horses as obviously intended, it would have been impossible for the Atkinson party to climb up the deep ravine on foot, and the intense sun, coupled with the burning sand of the steppe and lack of water, would soon have killed them all. And Lake Alakol’s water was to prove salty and bitter.

Riding up a great ravine from the lake, they passed from a morning of intense heat to a night in snow-clad mountains. At the top of the pass Thomas shot a large black eagle, much to the delight of their Kazakh companions; Lucy regarded these birds with the greatest dread, ‘in constant fear of them flying off with Alatau. They frequently carry off lambs, but I had not the slightest desire that Alatau should visit one of their eyries, to serve as a meal for their eaglets.’

On 26 July after further travels they returned to their old quarters on Alakol, getting up before sunrise for an early departure. The dogs had been very uneasy during the night, but although the Atkinsons were up many times to investigate, nothing untoward was seen. Then, just as they were to start off, one of their three Cossacks (whom they called Falstaff) noticed four men prowling about. Thomas ordered both Cossacks and a Kazakh to ride towards them and mounted his own horse to follow, leaving Columbus with Lucy, but she successfully entreated Thomas not to leave her and Alatau, knowing that he was a better shot than the three Cossacks put together. As soon as the four marauders saw they were to be pursued they rode off fast towards the head of the lake, ‘our men’ following at a furious speed.

‘The chase was an interesting one’, Lucy noted coolly. For a full twenty versts she and Thomas were able to watch it almost entirely. But they all became so small that ‘even with the glass we could not distinguish them’. Suddenly those left behind noticed four men creeping towards them but, seeing they were observed, they disappeared and soon rode off, perhaps a ruse to draw everyone away from the camp – if so, unsuccessful. After some two hours the pursuers returned leading a camel, and George, their third Cossack, carrying a long lance. It appeared that they had caught up with the marauders, who attacked the Cossacks with the lance but missed, and George wheeled his horse round suddenly and grabbed it, at which the miscreant shouted furiously, ‘We have tracked you for the last fifteen days, but you shall not escape us; we will take you yet.’ After further skirmishes they rode off. The Atkinson party reloaded their pistols and followed them for some time, then decided it was safer to return to their camp.

In these journeys in Semirechye the Atkinsons had to cross many streams and rivers, not a few of them rapid. On the front flyleaf of Thomas’s ‘Rough Notes from my Journal’ for the year 1849 he lists some of them: nine to cross and re-cross ‘after leaving Philonka’s aul on our way to the Ala-Kool’ and another six ‘between Bek Sultan and the Tarbogatie’. Some rivers the group had to ride into together to support each other, and Alatau was always on a parent’s saddle. How he survived seems a miracle. The Kazakhs always made sure that Lucy was in the middle and held on to her dress to keep her safe. When there were deep and broad streams to cross,

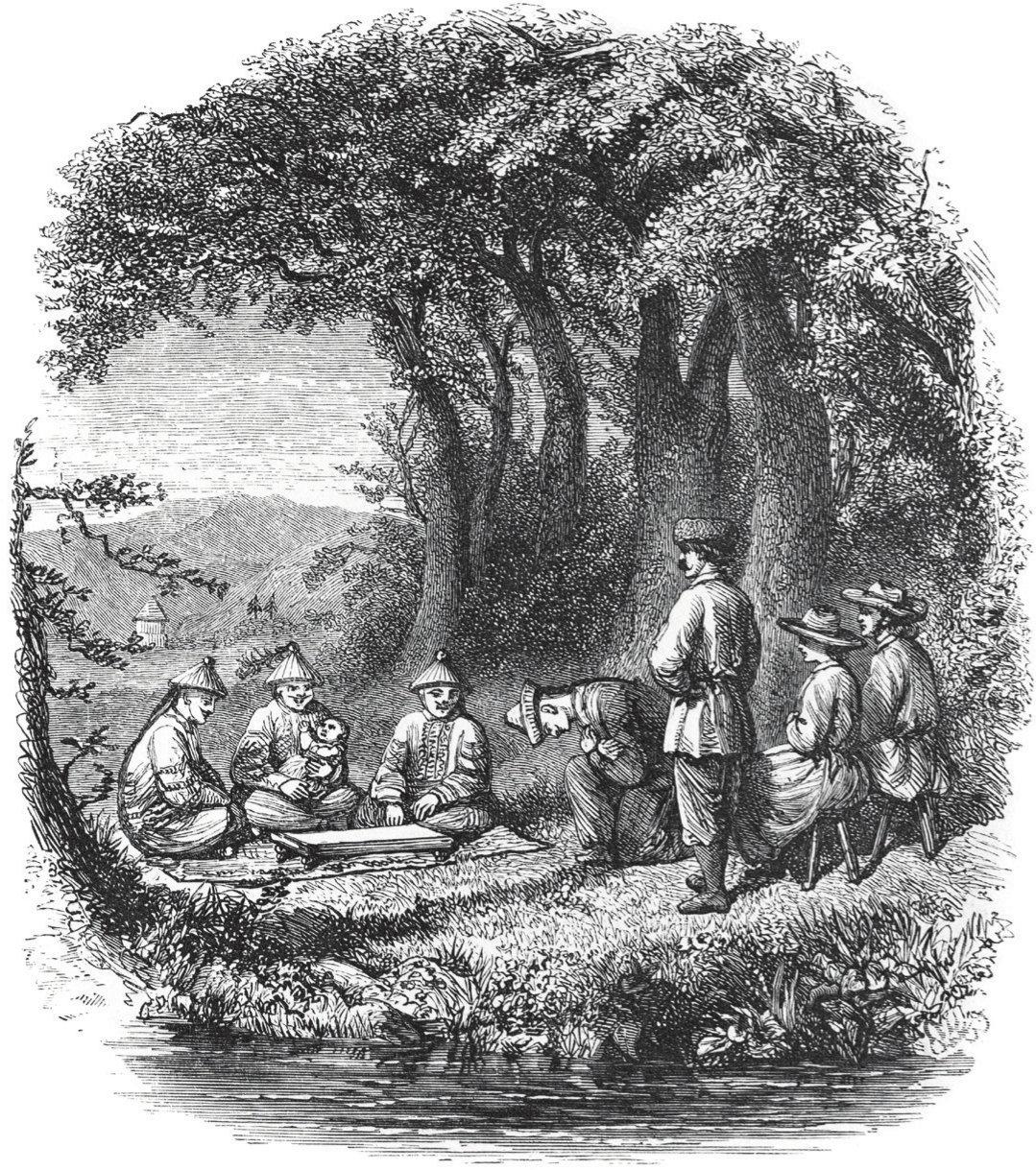

‘Sultan Bek and family’

The largest and wealthiest Kazakh in the steppes, according to Thomas, with 10,000 horses, and camels, oxen and sheep in proportion. In Thomas’s sketch he is posing with his family and berkut (an Asian golden eagle, wingspan average 2.21 m), with which he loved to hunt deer: a Kazakh tradition that continues to this day.

I used to retire behind the reeds or rocks, as the case might be, and, stripping, put on my bathing gown, with my belt round my waist; and tying my clothing into a bundle, boots and all, I jumped on to my horse – merely holding tight on to him with my legs, there being no saddle – and swam him across in the company of a Kirghis, he gallantly carrying my bundle for me; when I would again retire with my bundle, to re-equip myself. These are the sort of things we have to do in travelling. At first I used to feel [I will not say timid, but] my heart beat quicker; now I think nothing of it. I am vastly altered since leaving Petersburg.

Another hazard was the wild horses the party sometimes had to ride, caught fresh from the herd, some perhaps never broken in – or even mounted before. Once Lucy was badly alarmed when she had Alatau on her saddle and her horse began to shy. Luckily she was able to quieten him. Another time, fortunately without Alatau, she had thrown her cloak round herself in a storm and when it cleared she asked Columbus, riding nearby, to take the cloak and roll it up, since her own horse was rather wild. But his horse was also rather wild and he found it difficult to approach her. The cloak fell from Lucy’s shoulders, making her horse shy very badly. Columbus tried to ride up but this made Lucy’s horse worse and he galloped off across the plain at full speed. ‘No efforts of mine could stop him, so, sticking to him like a leech, I waited patiently till he should either tire himself or be caught,’ as Columbus was now galloping after her. A Kazakh now joined in the chase and began hallooing as loudly as he could, but this only made matters worse and Lucy’s horse sped on even faster. Only later did Lucy understand that the Kazakh was shouting for Columbus to stop his pursuit, and when he did so and Lucy’s horse no longer heard galloping behind him, he gradually slackened his pace and slowed to a walk.

Lucy was afraid to turn him till he became quieter, so looked round and saw the Kazakh far off, walking beside his horse towards her, while Columbus approached carefully and seized her bridle, making Lucy fear the horse would throw her. But Columbus stroked him and was able to calm him. When the Kazakh arrived on the scene he patted Lucy on the back and indicated how proud he was of her,

and then showed me what a Kazakh woman would have done under similar circumstances. First, he commenced screaming, and almost set my horse into another fright, and concluded by falling from his horse. He remounted and again patted me with evident delight…. We had several miles to ride back, and I did not at all thank my animal for giving me a run for nothing. On reaching our party, I received so many congratulations at my safe return, as also for my bravery that I verily believe if we had stopped longer in the steppe, a woman would not have been looked upon as such a contemptible being as they consider her to be; for the men now began to notice me, a thing they had scarcely deigned to do before.

Crossing the steppe between the large and small lakes of Alakol with the sun sinking fast, they pitched camp near the small sweet-water lake as far from its reeds as possible on clean white sand. All was still, ‘but night came on like a racehorse, and then we heard a most unwelcome sound amongst the reeds … our old tormentors the mosquitoes commencing their music’. With an extraordinary degree of optimism, Lucy crept quickly into bed, ‘hoping they might not find us’. For long they could not sleep because of both the vivid lightning and the heat from the ground, and when they did sleep they were soon woken by ‘the blood-thirsty creatures. There were, I am sure, millions in our tent; they positively maddened me, and I became alarmed lest they should devour the boy.’ Thomas rose and went outside to see what, if anything, he could do to keep them out, ‘but his exit was not so rapid as his retreat back into the tent; he had not gone ten paces, before the horrible things seized upon him with such energy, that he was glad to array himself in his chimbar and boots’. Lucy prayed that a breeze would spring up to bring some relief, and her prayers were more than answered. It soon began to blow and indeed increased to a gale. The Atkinsons’ yurt collapsed over them, and their escort, summoned urgently, propped it up so that the three trapped inside could breathe, and secured the outside with weights. But at least the gale ‘entirely cleared us of the enemy’.

When they had gone to bed that night the lake had been like a mirror. Now in the night it began to break on the shore with a tremendous noise, and the wind whistled shrilly. At daybreak, with black clouds gathering, the party packed up the camp quickly and set off without breakfast. The rain soon caught them, however, turning the sand beneath them, so hard and dry on their arrival, into a quicksand into which they kept sinking, while on the lake the waves reached a frightening height.

They continued north-east and arrived in early August at a picket on the Chinese border near the town of Chougachac (Chuguchak). Their Cossack, Falstaff, tried to dissuade them from continuing, as a Tatar had told him that the Chinese would make them prisoners. But Lucy laughed at his cowardice, and when he saw that the visitors were determined to proceed, he ‘pleaded indisposition’, took over from Columbus near the camels and dropped well behind at the first sign of the border. As they approached the picket, the distant town and its minarets came into view – this was Xinjiang, a Uyghur41 and therefore Moslem area, which the Atkinsons very much hoped for permission to visit. The picket was their first sight of Chinese (the border officials were probably Chinese rather than Uyghur) and Lucy was struck by their costume: their boots of black satin with high heels and thick soles, while their jackets, silk or satin for the superiors and blue cotton for the servants, pleased Lucy ‘amazingly, and were really pretty’.

A ceremonial now began. One Chinese servant ran forward to announce their arrival, gesturing for the Atkinsons to remain where they were. He soon returned and conducted them into a courtyard where the visitors were astonished to find the officer in charge playing with a goose. He stood up and Lucy was ‘completely wonderstruck at his height, Mr Atkinson [who was tall – 5ft 11ins] appearing quite a small man in comparison’. He received the arrivals with great courtesy, ushering them into his room, bare of furniture except for a raised platform (his bed), on which he seated them, and soon the place was filled with curious Chinese. Why did they wish to visit China, the officer enquired? Thomas explained that, being so near, he would like to pay his respects to the governor and visit the nearby town of Chougachac (as Lucy spells it). The officer thereupon invited them to pitch camp and promised to send a despatch to the governor with a response likely that same evening.

The Atkinsons retired to their yurt and were joined for tea by their ‘new friend’ with his secretary and interpreter, who were intrigued by all they saw, ‘examining everything most minutely’, and Lucy was not sure whether she was not the greatest curiosity. They had, they said, been stationed at this picket for three years and, with another year to serve until they could rejoin their families, complained bitterly about the long separation from their wives.

Next morning two officers and three soldiers rode up to the Atkinsons’ yurt, with short stirrup-straps like the Kazakhs’, sitting their horses elegantly and slung with bows and arrows (although one carried a lance). All were tall, perhaps selected in order to see over the reeds and the approaches. The officers dismounted and went into the yurt but, having brought no interpreter, Thomas and Lucy could not understand a word. Judging from the officers’ faces, however, they were delighted to meet strangers and accepted the offer of tea. But before Lucy had poured it out, the soldiers entered and said something. At once the officers got up, shook the Atkinsons warmly by the hand, shot out of the tent and galloped away fast.

It seemed that they had arrived from another picket to have a look at the, doubtless rare, strangers, and the Atkinsons soon saw why they had fled so fast: they had seen their superior officers and retinue on the road from Chuguchak. Two hours or so later their first Chinese friend came to announce the arrival of three officers from the town who, he said, would be very pleased to see them. Lucy put on her hat – decorum must be observed – and asked Columbus to take care of Alatau (she calls him again ‘the child’) in her absence. Their Chinese friend was really shocked to see that the Atkinsons meant to walk: far too undignified; so they ordered their horses. And when he realised they intended to leave Alatau behind, he was very concerned and insisted on him coming too, so Lucy put his hat on and told Columbus to bring him.