I

ON 16 JUNE 1850 they left Barnaul,1 stayed in Tomsk for three days, inundated with invitations, and started into East Siberia – ‘a frightful journey over roads fearfully cut up’ after a month’s continuous rain. On reaching the town of Krasnoyarsk on the Yenisei they were lucky to find, on a visit from his base in Irkutsk, the enlightened and reformist Governor-General of East Siberia Nikolai Nikolaevich Muravyov (a relative of Lucy’s previous employer in St Petersburg) and his French wife. The next day both Thomas and Lucy had a long interview with him and, knowing no one else in the town, according to Lucy they dined with the Muravyovs every day for a week – a little odd, unless they were merely two of many guests. But Thomas’s journal records: ‘He offered to aid me in every thing that he could and gave me a paper to Travel in the Governements of Yenissea and Irkoutsk [Yeniseisk and Irkutsk] – ordering every thing to be open to me’ and ‘desired’ the Atkinsons to reach Irkutsk by mid-August as he would be leaving for St Petersburg on 1 September. ‘The General’, Thomas added, ‘was greatly delighted with my pictures of the Altin Kool.’2

While still in Krasnoyarsk the Atkinsons called on the Davydovs, Vasili Lvovich and his wife Alexandra Ivanovna, another Decembrist exile family. The two were later joined by their daughters, who had been cared for by relatives.

As regards to Exiles I presume you would like me just to tell how I found them [Lucy was to write to her future publisher, John Murray]. You must know I was received by them all as a sister. I having lived in the Mouravioff family during eight years: when I entered the house of Mouravioff and Jakoushkin [both Decembrist exiles] and mentioned my maiden name [Finley], I was immediately recognised as I was always considered part of the family. Others of the Exiles with whom I had no acquaintance received me with open arms so soon as I said where I had been living. The name acted as Talisman. You must understand my General Mouravioff is brother to the Hero of Kars and cousin to Sérge Mouravioff who was hanged in Petersburg – he was likewise himself implicated in the affair of 1825 – he was nine months as prisoner in the Fortress.3

When her husband appeared on the scene he told the Atkinsons:

It was always a source of regret to me that we were betrayed by an Englishman: whether we were right or wrong is not the question; but that Englishman pushed himself into our society, feigning to be our friend, whereas he was acting the ignoble part of a spy and a traitor.

He was referring to John Sherwood, son of a mechanic from Kent who came to St Petersburg with his family in 1800 and joined the Russian Imperial Army. While serving in the south of Russia he came across some of the conspirators and wrote a letter exposing the organisation to the Tsar’s Scottish doctor, Sir James Wylie, to be passed on to the Tsar himself (Alexander I).

They returned west to Achinsk by perekladnoi, ‘a post-carriage changed at every station’ – nearly 200 versts without springs – and had never been over such bad roads. Lucy found:

It was impossible to sit, stand, or lie; and what made it worse for me was that I held the child in my arms, so that when the shock came he might not feel it. It was dreadful, not an instant of rest the whole way. How my poor neck ached! indeed, I ached in every part of me… [Why didn’t Thomas help, one wonders?]

Further south, at Minusinsk, the police master invited them to stay; this ‘most gentlemanly man’ had been exiled on a political charge and later pardoned but still not allowed back to St Petersburg. He was a clever man with ‘a vast amount of information’, but his wife (a very kind, good-hearted woman) ‘could not even read’. They had adopted two children, having none of their own – one of whom, now a young lady of seventeen, they had found lying in the forest; both were well educated by local Decembrist exiles (three of them living in Minusinsk at the time). ‘It was painful to witness the desire they had to return’ to the capital and ‘appeared weary of … existence’.

They took a 50 km detour from Minusinsk to the village of Shushenskoye4 to see another Decembrist exile, Peter Fahlenberg. He had previously lived in Minusinsk where, to earn a living, he had begun a successful school until the authorities forbade it. Now an old man, he had moved to the village to grow tobacco ‘for his support’. ‘There was no mistaking the noble gentleman, in spite of his costume and all that encompassed him.’ He was pleased to see the visitors and shook hands warmly. But, to quote Lucy again,

I do not know anything more painful than to find a talented man with a highly cultivated mind placed in such a position as that in which we found Mr Fahlenberg. He owned to the justice of his banishment, but deprecated in no measured terms the severity with which he had been treated. ‘I wished for nothing more’, he exclaimed, ‘than to gain an honest livelihood, whereas they have forced me to do this,’ and with bitterness opened his window, and showed the field of tobacco he was cultivating. ‘This,’ said he, ‘is the noble work on which I am obliged to employ the few remaining years of my existence; surely the punishment we have already undergone is more than adequate to the crime we committed. Even my wife,’ he continued, ‘was persuaded by her friends that I was dead, so remarried; but she would never have done so had she believed I still existed; of necessity I had no means of acquainting her to the contrary.’

A few years earlier, Fahlenberg had himself married again – ‘a very good and really a superior’ daughter of a Cossack – in order to have someone to care for him in old age. They had two children – a seven-year-old boy, ‘as rough and wild as any peasant’, and ‘a beautiful fairy-like’ girl of eight or nine whom Fahlenberg spent much time in teaching and who now spoke French well. Her parents very much hoped to get permission to send her to Irkutsk to continue her education, but Lucy doubted if it would be as good as her father’s tuition. Fahlenberg told the Atkinsons that ‘his great enjoyment’ was visits for a few days from his fellow exiles. But, when they left, he said, ‘I am once more left to my solitude, which for awhile is almost unbearable,’ for his young children and Cossack wife were not adequate companions for this highly intelligent and well-educated man.

Now in the heart of Eastern or Oriental Siberia, as Thomas was to entitle his first book, they rode along the banks of the Yenisei, one of the great rivers of northern Asia,5 draining a basin of 2.5 million square km (nearly a million square miles) north into the Arctic Ocean – a graphic example of Siberia’s enormous size. The Atkinsons found ‘pretty scenery’ along the river and camped in ‘most lovely spots’. They saw the distant Taskill mountains, part of the West Sayan range, ‘bedecked with a crest of snow, reminding us once more of our dear old friend in the Alatau’. They reached the village of Tashtyp where their Cossack escort at the time had been born – but had not visited for years – ‘every step of the road’ brought back some pleasant memories for him and yet more talk. He was very keen to see his adoptive parents: ‘Such good old creatures,’ he said, but as he had not heard from them for a year or more, he thought they might be dead. ‘Though I am not their real son’, he explained to Lucy, his eyes full of tears, ‘I love them equally the same.’

They were indeed alive and begged Lucy to approach the Governor for their adoptive son’s liberty so he could return to them and his childhood home ‘at least till he had closed their eyes’. ‘The Russians,’ noted Lucy, ‘especially the lower classes, have an extraordinary love for children, and even when they are not their own they still show love and regard for them.’ When they left Tashtyp in a boat for the Abakan river, which flows into the Yenisei at Abakan, the old parents escorted them along the bank as far as possible.

They then bade us adieu, and, taking an affectionate leave of their son, blessed all; and, commending us to the care of the Giver of all good, knelt down as we pushed into the stream, and remained kneeling till a bend in the river hid us from their view.

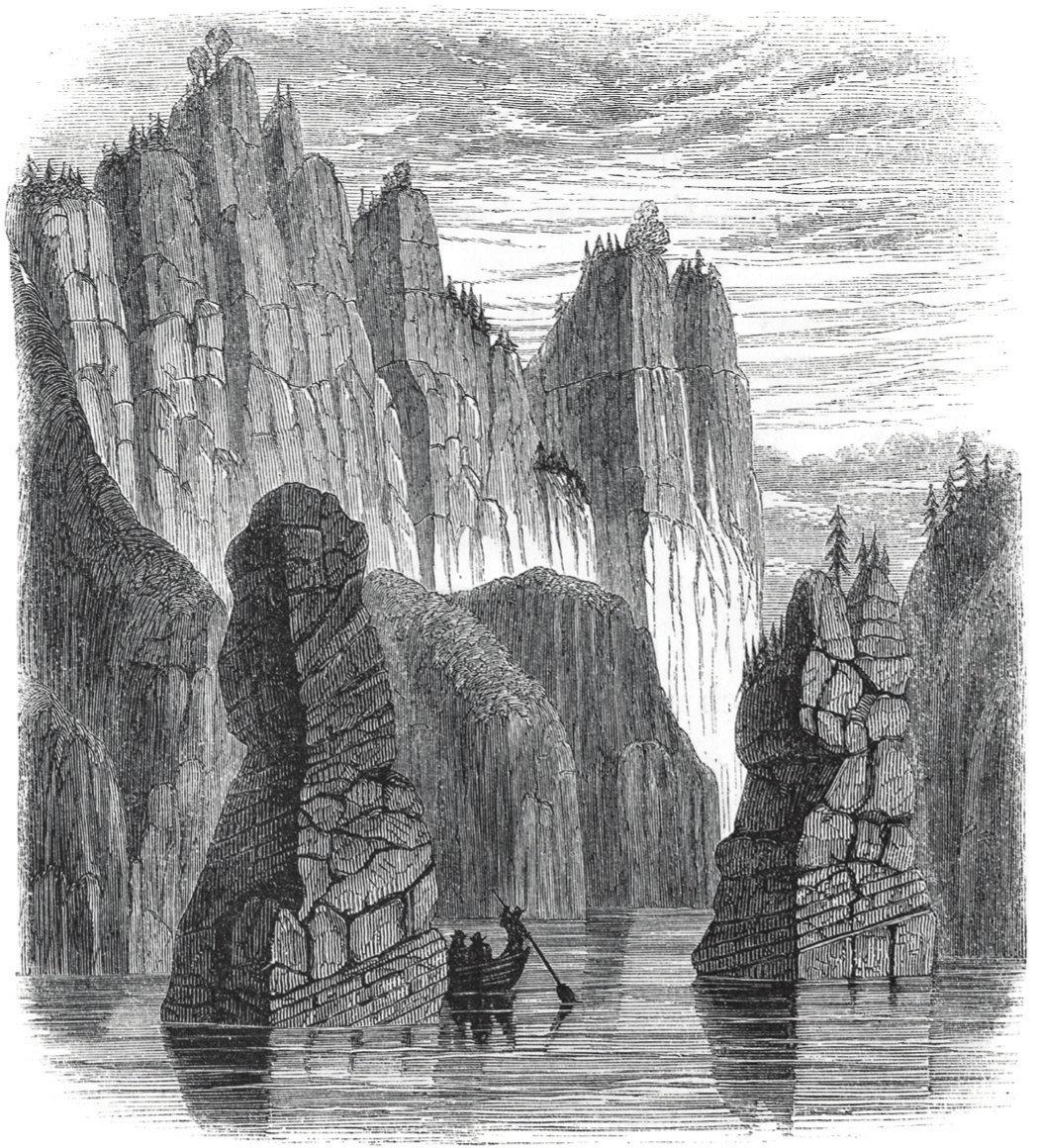

‘Singular formation’

Parts of the Abakan reminded Lucy very much of the Altin-Kul ‘with the same lovely scenery’, and every night they slept on its shores in a balagan. She wrote: ‘I know nothing more agreeable than the falling asleep where not a sound is heard save the rippling of the stream close by, or the rustling of the leaves in the branches above us.’

In late July they returned to Minusinsk, again staying with the police-master. The weather was extremely hot and the rooms ‘felt oppressive’, particularly because they were kept dark due to the heat. When a servant announced lunch they did find a little light in the dining room and Lucy vaguely made out that the table was ‘one black mass … every particle was densely covered with flies. Not a pin’s head of the cloth to be seen.’ Their host made light of the matter, explaining that every house was like this in summer and it would be impossible if they did not keep the doors and windows shut to keep out the heat. Lucy says nothing of any after-effect of that meal.

They then travelled north with three Cossacks along the east bank of the Yenisei, and a few days later began to ascend the Abakan river. Thomas made several sketches on the river – ‘very like parts of the Altin Kool’ – before they returned to Minusinsk.

Surprisingly, they bought a large boat there (with what money? one might well ask), had it altered for their accommodation – a whole day’s work but no details given – and all their friends came to take ‘a most affectionate leave’ of them on 23 July, each with a message to a friend in exile. But Fahlenberg said that the Atkinsons’ visit had done him no good – he had forgotten his sorrows only temporarily and would try to forget their visit.

They went on some 300 km further north down the Yenisei towards Krasnoyarsk, ‘a delightful voyage’, thought Lucy, with pretty scenery, and stopped from time to time for Thomas ‘to sketch some lovely view’. At night they bivouacked in the woods or at some village. At one such village the chief man entered their room, standing bolt upright at the door but, courteously received by Thomas, he relaxed and welcomed them to the village and, on being handed their ‘road papers’, gave them a very low bow. Having looked at them, he asked if they were Russians. No, they said. After a pause, he bowed low again and asked, smiling, if they were Germans. No, they said again. ‘The poor fellow took a long breath, apparently at his wits’ end’ and for some ten minutes looked first at Thomas then at Lucy but still none the wiser. (At that time ‘nemtsy’ or Germans meant all Europeans, so they should have answered yes. No wonder he was at a loss!) ‘At length he cleared his throat, scratched his head and, smiling very sweetly, once more bowed to the ground and inquired if we were Groogians (meaning Georgians).’ At their third no, Lucy says, the poor man’s hair

appeared positively to stand on end; he looked at us quite aghast, and wildly exclaimed, ‘Is it possible that you are Chinese?’ and, throwing down the papers, rushed headlong out of the room, whither no persuasions could induce him to return.… All the inhabitants of the little village kept a respectful distance; ordinarily they crowded round us to have a sight of the wild animals.

When they reached Krasnoyarsk – founded in 1628 as a Russian border fort on the Yenisei6 – they drove to the Governor of the province, Vasily Kirillovich Padalka, and his wife Elizaveta, daughter of a previous Governor-General of Eastern Siberia. Padalka was known – or was to become known – for developing the area’s gold resources, and the Atkinsons remained with them till 5 o’clock and the next morning resumed their journey, receiving en route ‘a most pressing invitation’ to a priisk or goldmine further north, so Padalka’s dinner talk could have proved most useful.

Ahead of them almost immediately, however, lay the great and dangerous rapids on the Yenisei, and it was very difficult to find boatmen who would take them. At the river station nearest to the rapids their old steersman summoned the two rowers to a prayer.

They instantly dropped their oars and stood up in the boat while the old man breathed forth a prayer for our safety over the coming danger. Lucy and I joined our prayers…. [Thomas’s journal, copied word for word in Lucy’s book.] Our men then plied their Oars and soon took us into the Middle of this mighty Stream … about 8 versts distant from the Rapids we could hear the Roaring of the Water and … [soon] we looked upon the Boiling flood. Three minutes carried us like a shot on a line with the first Rocks. At this moment the scene was truly grand. Our little boat was tossed like a feather and carried on at a fearful speed. We soon reached a place awful to look upon. The water recoiled from some sunken rocks and was tossed up in waves which looked as if they would swallow our little craft – there was not a heart on board that did not quail at this site. A few moments carried us over this into the boiling current and on we shot.

By 16 August7 they had reached the confluence of the Yenisei with its tributary, the Angara, ‘a fine river’, thought Thomas, as ‘clear as crystals’, and the waters of the two rivers could be seen side by side ‘for a great distance’. Oddly, both Thomas and Lucy mistakenly but consistently write of ‘the Tunguska river’ instead of the Angara, perhaps simply confused, maybe indeed deliberately, as the Russians would not have wanted an uncontrolled Siberian gold rush. Thomas was very keen to visit the priisks to which they had been invited, and 50 km up the river they left their boat at the village of Motygino and travelled on perekladnoi, changing carriages or horses at post-stations with their luggage, passing through miles of burnt-out taiga: all ‘blackened and charred stumps of trees … scattered in all directions, some still smouldering’, Lucy noted. The fire had been burning for two weeks across an enormous area and was put out only by some heavy rain. Lucy saw that fire in the taiga was not uncommon since everywhere was ‘so dry that the least spark will set them burning, and the Cossacks and hunters are exceedingly careless’.

They found that the gold-mining area was one of ‘low hills covered with dense forest of larch and picta’, with rocks of slate difficult to drive through, ‘while along the vallies is a deep Morass impossible to traverse without the wooden roads [made of logs or planks] which had been constructed’. In this remote province gold had been found in 1832 and then in many small rivers through the 1830s. It was unsurprising that the Atkinsons’ gold-mining friends were wealthy: the most profitable river (the Small Kalami)[Kalmanka?] produced 1,704 poods (about 28 tonnes) of gold in the years 1842–66.8 According to the Atkinsons, the gold was found in slate ‘washed down from the hills, covered by a bed of earth about 3 feet thick.’9 An astonishing workforce of 9,000 men – all convicts – was washing and digging for the precious metal. All of them had been deported from European Russia and were guarded by only eighty Cossacks – enough, it proved. In rain their work was ‘really frightful’, wrote Thomas, but the men were well fed and given vodka on some feast days.

Mr Vassilievsky, the mining area’s senior police officer,10 took the Atkinsons to his house at Peskino, on a small river,11 where he had invited an English couple, Mr and Mrs Bishop, to meet them – ‘most agreeable people’ (presumably the husband was working at the priisk). They felt very at home, passing ‘a most delightful evening’, and next day had ‘a good English dinner of Roast Beef’. Thomas made a sketch of Peskino, its priisk and two others and had himself and Lucy weighed on a scale doubtless used for the gold. In five weeks she had gained 2 lbs, and was now 2 poods 27 lbs, while Thomas had lost 7 lbs and now weighed 4 poods 7 lbs.12

While at the priisks Alatau, now nearly two, was ill for five days. For once Thomas mentions him in his journal. Alatau was very unwell: ‘a good deal of fever caused I fear by his remaining so long [in] the river bathing’, and Lucy agreed – ‘once three quarters of an hour, when the water was not very warm’; ‘he was so passionately fond of bathing’ that it was difficult to keep him out of the Yenisei.13 Lucy was proud that her young son had learned to walk at the age of nine and a half months without being taught, but contrarily he was late to talk – his parents were afraid he might be dumb – and then began talking in whole sentences, probably confused by the English in which his parents (particularly his father) spoke, whereas strangers spoke in Russian. He had grown tall and, Lucy says, ‘was as wild as a young colt; never quiet but when he has a book, then he sits for hours and talks to the pictures. Toys he has none, nor did he ever have any.’ ‘And his hardy conduct’ won him admiration from all sides, preceding his arrival in Irkutsk, where Governor-General Muravyov, whom they had already met, told Princess Volkonskaya (of whom more anon) that ‘he should like to steal him. I [Lucy] can tell you I am mightily puffed up at all the praise he receives.’

After visiting several priisks they stayed at Motygino, where they had left their boat with one of their two owner friends, the wealthy Astashev of Tomsk. He was there with his wife, and Lucy found that their ‘little expedition’ was made ‘most agreeable [by] the presence of two or three ladies who had accompanied their husbands for the summer’. But it sometimes stopped the ever-interested and ever-observant Lucy seeing all she might have done ‘as without them I might have wandered about everywhere, and now I was obliged to associate with my sex’.

Astashev himself, she continued, was

a most gentlemanly man … who received us with all the kindness imaginable. Alatau so won on the affections of himself and his wife during the two days we stopped with them, that, having no children of their own, they wished to adopt him, said he should inherit all they had (and they were rich), and endeavoured to show how much happier the child would be, settled quietly down, than leading such a roaming life as we are doing; but, as you may suppose, it was of no avail.

The first night there Lucy bathed him and put him to bed, then Astashev asked to sit with him ‘till he fell asleep’. Lucy heard him telling Alatau not to wake her when he woke next day but to collect his clothes and leave the room, and Lucy was to find the director ‘had himself bathed and dressed the child, who was comfortably seated on his knees, perfectly happy, and as though they were old friends. And the night following, on going into the room, I found the child asleep with his hand lying in that of this great man.’ On the Atkinsons’ departure, the Astashevs took them part of the way ‘and I verily believe it was to have the pleasure of carrying Alatau; they would not permit me to touch him, or to do the least thing for him, and when we bade adieu tears stood in the eyes of the director’.

Their carriage had meanwhile been forwarded nearly 200 km east of Krasnoyarsk to Kansk and they were lent another one to get them there, from which they went directly on to Irkutsk, capital of East Siberia. They arrived on 11 September 1850,14 obviously intending to stay for some time – surely so that Thomas could transform his sketches into finished watercolours – as they rented (for 45 silver roubles a month) from a merchant’s widow, Madame Sinitsyn, a house pleasantly situated on the bank of the Angara river, with the Governor-General’s official (and grandly porticoed) residence a couple of hundred yards along the embankment, designed by Catherine the Great’s famous Italian architect Quarenghi and now known as the White House.15 For the first time in all their travels the Atkinsons now had a house to themselves: four nice rooms with a kitchen and its own entrance across a yard from the main dwelling house.

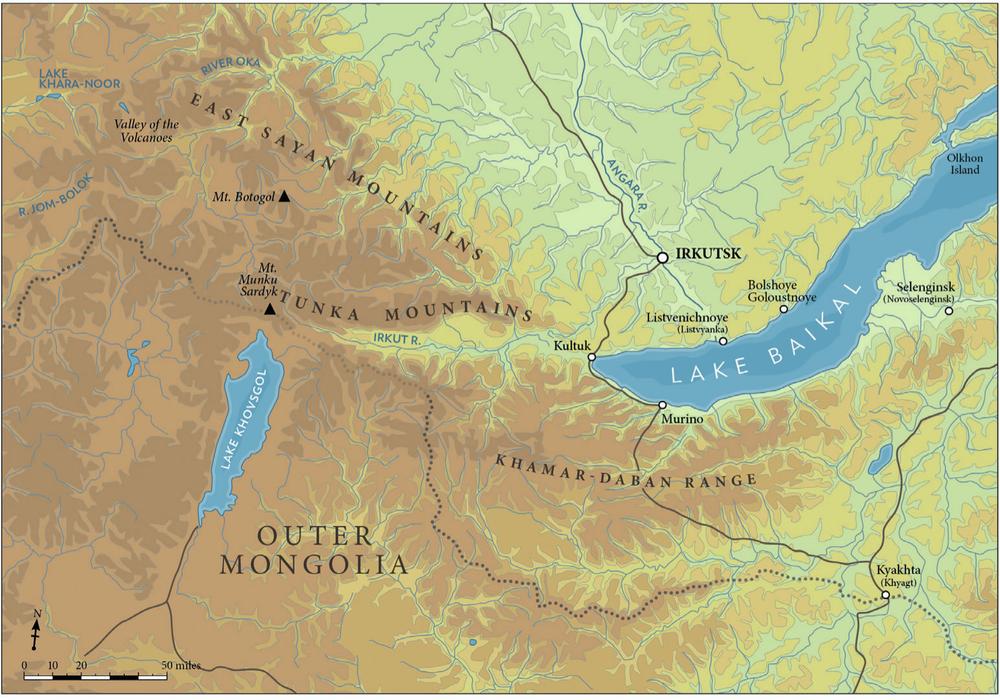

Lake Baikal and surrounding region

A few days later they woke to find the ground covered with snow, and the snow continued to fall. Thomas found it ‘most Strange to see the Swallows flying about seeking their food on such a Wintery Morning’.16 He spent three days working on a watercolour of the Altin-Kul for Mr Vassilievsky, their friend of the Peskino priisk. The first day he sketched it, the second day he ‘Began colouring’ it and the third day he finished his ‘drawing’ and thought ‘It makes a most beautiful picture’. And the next day he was ‘At work on my view number 158 of the Altin Kool. There is much labour in this Picture but the general effect will be grand.’17 After another three days’ work he finished it ‘and a splendid picture it is. Prince Troubitskoi [one of the leading Decembrists] and Mr Taskin18 thought it a great work’.19 The following day he was ‘Working at the Waterfall number 149’, his third watercolour (at least) of the Altin-Kul – ‘I expect to produce a fine Effect with the Trees that are tumbled down the Rocks.’

That day had begun with ‘A fine Frosty morning with a fog rising from the Angara. The poor swallows are still here altho the snow is laying on the ground. How anxious the[y] seem to be to get into the sun – they sit on our window shivering with cold’:20 one of Thomas’s occasional sympathetic comments on the animal kingdom. He obviously loved dogs, but he and Lucy must have tired out many horses, with only one or two acknowledgements of them in his journal, and he empathised with certain humans – although not all.

Lucy meanwhile ‘had to go through the usual round of visits necessary for strangers to make on their first arrival’. Madame Muravyova, the Governor-General’s wife, whom the Atkinsons had got to know in Krasnoyarsk, kindly invited Princess Trubetskaya, the Prince’s wife, to meet them (probably leading to the visit by her husband), and she provided for them a list of ‘the persons to whom it is considered indispensable for us to introduce ourselves’. They had, too, letters of introduction to Princess Volkonskaya, the leading Decembrist wife, known as ‘the Princess of Siberia’ and widely loved in Irkutsk for her good work in the local schools, hospital, new theatre and concert hall and ‘her benevolent influence on Governor Muravyov, … [to her] ‘the most loyal, kind, and gifted man on this earth’.21 And it was these three ladies whom the Atkinsons tended to visit most. In the Trubetskoy and Volkonsky houses they ‘generally meet their companions in misfortune and some of Russia’s cleverest men grown old in exile’. But besides the Decembrists there were many other exiles in Irkutsk who had settled down well, some in ‘very handsome houses’.22

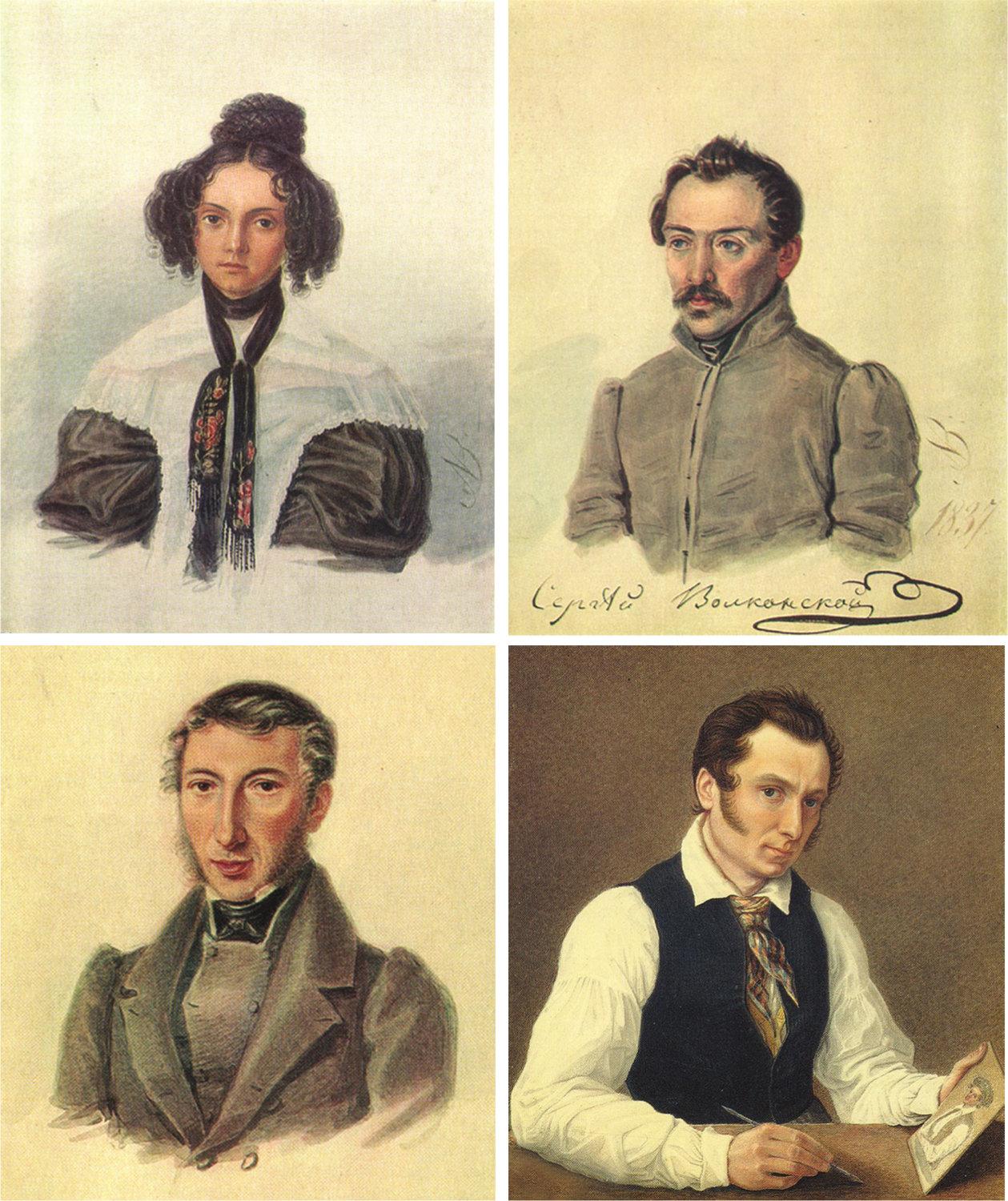

The Decembrists: Maria and Sergei Volkonsky, Sergei Trubetskoy and Nikolai Bestuzhev

The Atkinsons visited many Decembrists in Siberia including, in Irkutsk, the Volkonskys and Trubetskoys, whom they got to know well. (Prince Sergei Trubetskoy had been one of the organisers of the Decembrist movement.) In both cases their wives had joined them; all were stripped of their titles and great wealth. Southeast of Baikal the Atkinsons visited Nikolai Bestuzhev, a talented artist farming with his brother (and sisters), who painted himself and many of his fellow Decembrists. Volkonsky was one of only nineteen of the 121 exiled Decembrists to return to Russia in 1856, broken in health but still true to his beliefs. He died in 1865, two years after Maria.

Lucy found that Princess Volkonskaya23 (who, incidentally, had had an English governess) was ‘a clever woman’ but had ‘lived to regret her voluntary banishment’. She had chosen to join her husband – ‘whatever your fate I will share it’24 – after only one year of marriage, aged only twenty-one, leaving her new-born son behind with her mother-in-law, and probably did not realise she would never see him again. Travelling some 4,500 miles by sledge in the freezing winter with only a maid to accompany her, she found her husband shackled in the dark, underground in the silver mines of Nerchinsk far east of Irkutsk, and ‘knelt on the filthy floor and kissed the chains’.25 Altogether she and ten other Decembrist wives or fiancées had followed their menfolk to Siberia26 and only in 1835 was Prince Volkonsky freed from hard labour, replaced by lifetime banishment. And not for another ten years were the Volkonskys and Trubetskoys allowed to settle in Irkutsk, East Siberia’s cultural centre. Volkonsky told Lucy he had been an impetuous youth who visited France, England and Germany and, as she went on, ‘then returned to my own country, where I unfortunately found that the effect of those travels [the exposure to democracy] was to lead to Siberia and the mines’ [i.e. Nerchinsk]’,27 along with his fellow plotters for about a year before being transferred to Chita.

Decembrists’ house in Irkutsk

In this house, now a Decembrist museum, lived Princess Maria Volkonskaya, wife of the Decembrist Prince Sergei Volkonsky, who chose to live across the courtyard.

But despite her sacrifice and dedication, the Volkonsky marriage did not prove ideal. He, Sergei, spent much of his time on the acres he had been allotted near Baikal, and when in Irkutsk lived in a hut in the courtyard of the large house where Maria lived with her later children. The Atkinsons found him ‘simple and unostentatious’ and, according to Lucy, he was well known to all the peasants in the market where early each morning he would buy his family’s necessities for the day – after haggling and hearing the latest news from his many peasant friends. Then

you might see him wending his way home with geese or turkeys, or something or other, under his arm, and wearing an old cap and coat which would be almost rejected by the poorest peasant, but with a mien dignified and noble, and a countenance that it would do your heart good to see.

‘He is never to be seen among the gentry’ of the town, Lucy wrote, only the peasantry, and he explained he always liked ‘to keep his place’, having been stripped of all his ranks and noble title. On one of his many visits to the Atkinsons, he brought ‘a companion in exile [Borisov] who has a great taste in drawing’ by which he was able to maintain both himself and his brother, ‘unfortunately deranged’ through grief. The artist’s flowers and birds, painted ‘in most exquisite style’, had unfortunately faded away badly after a few years as his watercolour paints were bad, so Thomas presented him with a box of Winsor and Newton watercolours which Borisov greatly admired. He in turn presented Lucy with six ‘superb’ drawings of Siberia’s birds, fruit and flowers ‘made expressly for her album’, which she greatly appreciated.28

Lucy mentions an interesting belief in the domovoi or house spirit: goodwill offerings are ‘daily made to him’, and if the occupants move, they tell him they will take him with them and offer him a broom to travel on.

Their first week in Irkutsk Lucy asked their landlady if a banya (traditional steam bathhouse) could be heated and arranged so that Thomas could go first, as she found the great heat ‘insupportable’. When all was ready she asked if Madame Sinitsyn’s coachman could go with him (customary in many places) and looked aghast at the idea of Lucy not going – ‘the very idea set me off into a fit of laughing, which highly offended the good creature’ who maintained that every good wife should wash her husband.

One day Lucy heard the story of a woman she saw in the bazaar. Past her prime ‘but still good-looking’, she had been lost and won at cards. Married young – ‘a Siberian beauty’ – to a rich but carefree man, ‘a great gambler’ as so often in Siberia, in a few years he ran through the greater part of a large fortune. His wife knew nothing of this; but her eyes were opened when one day ‘a gentleman arrived at their home … and claimed her for his property’. All through the previous night and well into the morning the two men had played, and the formerly rich husband was now ruined, having lost every kopek as well as ‘land, house, furniture, horses, and even wife; she was his last stake’. Yet, against all the odds, she had now ‘lived with her victor for twenty years, leading a most happy and exemplary life’.

Having arrived in Irkutsk in mid-September 1850, Thomas wrote to Nicholas I the next month explaining that, when four years earlier he had petitioned His Imperial Majesty’s permission to visit the Ural and Altai Mountains29 to sketch their scenery, he believed the Altai chains extended from the river Irtysh (tributary of the Ob) to the sea of Okhotsk (on Russia’s far eastern coast), but was now informed that the Altai did not extend beyond Lake Baikal (indeed it ends some 800 versts short of the lake) and that he could not proceed further without his Imperial Majesty’s gracious permission. He continued, ‘Having now devoted four summers in sketching the scenery of this great Mountains System’ in which he had made dozens of views (according to the lists in his diaries) of scenes never before attempted, he now humbly solicited the Tsar’s most gracious permission to continue his journey ‘and sketch, in the provinces of the Grand Baikal, Nertchinsk, the Yablonoi [Yablonovy Range], and Stanovoi Mountains, also the Volcanic Region of Kamchatka, as this would enable me to complete my views of this great Mountains System’. And he ends as before with his usual deference as: ‘Your Imperial Majesty’s most devoted and most faithful servant, T.W. Atkinson.’

This is a curious letter for several reasons: he would surely have known before setting off from St Petersburg that the Altai (probably considered more than one chain then) stopped well before Baikal and the Sea of Okhotsk and that the huge area he mentions is hardly one great mountain system but several; and he perhaps tactically omits the Kazakh steppe and mountains for which he only had permission from the Governor-General of West Siberia. It is possible, of course, that Governor-General Muravyov may have told him to try his luck with the Emperor. In the event permission was not forthcoming. It is also quite remarkable that he wanted to continue their epic and lengthy travels – for perhaps another three or four years.

Thomas ended his journal for 1850 the next day after his letter to the Tsar, following it with a ‘Catalogue of Sketches made in 1850’ (in fact only between 9 July and 15 August), basically of the Yenisei and Abakan, numbering and dating each: a total of twenty-eight, sometimes two in a day and quite obviously sketches only, perhaps simply pencil in view of his statement about adding colour. He resumed his journal only in June 1851, the day they left Irkutsk, nearly seven and a half months later. We do not know what he was doing all this time but we must assume he was painting up some of his many sketches while waiting for the Tsar’s permission, which never came.

Towards the end of March 1851, the Angara thawed and the Atkinsons had to shut all their doors and windows as in winter the town’s refuse was dumped on the river banks in an attempt to stabilise them, so that the sun produced ‘anything but a perfume of roses’ which led to much mortality, particularly among children. This worried Lucy, as Alatau had suddenly been taken ill and she was ‘forced to walk about continually with him’, which was difficult as he was getting heavier and would not allow his nurse (more expense!) to come near. His parents too were affected by the fetid air and resolved to leave the town early.

Lucy, doubtless remembering the useless young doctor at Kopal, would not hear of consulting a doctor but wanted to leave it to nature, where at least there would be a chance of survival, she felt. Alatau had become a great favourite of the Trubetskoy family and the Princess called to see him, knowing he was ill. She felt his looks had greatly improved since their arrival seven months before and Lucy, caring mother as she was, told her that she and Thomas had been horrified by his appearance when new-born: ‘anyone more atrociously ugly I never beheld’ although ‘the most good-natured brave little fellow’. The Princess consoled Lucy by saying he would grow up ‘a very handsome man, all ugly babies do, and instanced her own children’. ‘Not that Alatau is so ugly now’, Lucy considered, adding, ‘At least, there is a satisfaction in knowing that it is not his looks that gains him so many friends.’

But she was increasingly concerned about Alatau’s health. He ‘became very ill indeed, daily growing worse’, and everyone urged them to put off the journey they had planned to Lake Baikal. Instead, they decided to leave Irkutsk early in order to take him to a hot mineral spring. So in early June30 they left Irkutsk for what was to be four months. Thomas made two lists of the items they deposited with the mayor, Mr Basnin, and it is intriguing to see how much they had accumulated. His first, short, list was of his watercolours, which he calls either views or pictures: one of the Altin-Kul framed and in glass, eleven other views, two of them unfinished. (His previous sketches of the Urals, Altai and Kazakhstan must have been left in Barnaul to pick up on their way west again.) His larger list includes three large black boxes with shubas, clothing, books etc., a ‘Large Tin Colour Box, Medcine chest, Pistole case, candle box and Bonnet box’. How they thought they could stow all these on to a sledge back to Moscow is a moot point.

They set off to the spring, sleeping at Kultuk on Baikal’s south-west lakeside where they found Alatau worse, unable to walk, and Lucy began to reproach herself for leaving Irkutsk despite all their friends’ advice. Thomas believed that if the spring did not help they should return to Irkutsk. The next evening they reached the mineral spring they sought, one of an astonishing 300 in the Baikal area, many of them hot (up to 75°C) and with medicinal properties. Lucy was very anxious till she had immersed Alatau briefly in the bath into which the spring ran, then put him to bed, where he fell asleep so quickly and soundly that the Atkinsons went for a stroll, leaving a Cossack with orders to send for Lucy if the boy woke.

Six years before, the Archbishop of Irkutsk had built here ‘a small but pretty church’ and a tiny monastery among the trees where pilgrims and visitors could stay. Lucy found it a beautiful place: ‘so calm and quiet; and shut out from the noise of the busy world, with no other sound save the murmuring and rippling of the water as it flowed over the stones’, and Thomas was to produce here one of his best paintings.

While there they encountered a priest who told them they must avoid bathing Alatau in the spring,

‘A natural arch on Nouk-a-Daban, Oriental Siberia’

A mountain in the East Sayan range. Thomas included this (exaggerated?) arch among the lithographs in his first book. The river at right is possibly the Oka which, in another location, threatened the Atkinsons’ lives with its rapid and unparalleled rise one night.

‘for,’ said he ‘if you do, you will kill him certainly. Many,’ he continued, ‘come here thinking to cure themselves by these waters; but all die who bathe in them, not one survives; and I always warn them, but they will not be persuaded; we had a man died here about a month since, who came imagining this place would do him good.’ You may suppose [wrote Lucy] that every word he uttered went like a dagger to my heart, for I had been similarly advised in Irkutsk, but would listen to no one.

The priest entered our room, where he sat chatting a long time. I never watched for the departure of a guest with such anxiety as I watched for his; at length he took his leave, when I gave vent to my pent-up feelings in showers of tears. I had not courage to tell him that I had already bathed the child; and, with a heart over-flowing with grief, had been obliged to be gay and talk, the poor priest little guessing what anguish he had caused me.

Lucy cried herself to sleep and was woken ‘by a little voice calling out “I am hungry”’ – not surprising, as Alatau had eaten nothing since leaving Irkutsk three days before and was not strong enough to stand. Lucy found it was 5 o’clock and before breakfast she ‘plunged him in [to the bath] again, and from that hour dated his recovery’. The spring in fact improved him so much that his parents decided to stay on for a couple of days, after which he was very much better and able to walk again. ‘It seemed almost miraculous’ that such a change could have been produced in such a short time. But Lucy was very cautious about leaving him too long in the bath – ‘in the morning a single plunge’ and in the evening just a wash. Amazingly, this was almost the only time that Alatau was ill in that extraordinary childhood.

With him recovered they rode through the area looking for good views for sketches; a few days later, after a three-hour ride entailed crossing the Irkut river, a meandering tributary of the Angara that had given its name to the town, they rested on the bank ‘for two hours to give our jaded horses the means of getting a dinner’: one of the rare acknowledgements of care for their horses on which a lot of the seven-year journey depended.

Ahead of them now lay the mountains round Baikal, and Lucy writes of the ‘scenes of winter and summer’ they passed over, sometimes a night spent on ‘a carpet of flowers’, another on bearskins spread on the snow. In some places nothing had started to grow, in others flowers were in full bloom, and once they rode over a bed of ice from which emerged trees in bud. They rode on through thick woods with some views of the 3,000 m Tunka Alps, a branch of the Eastern Sayan range, 1,000 km long. Thomas found one of the summits ‘the most singular place’ he ever saw – a ‘Labrinth of Rocks and Lakes’, and rode back to his party camping in a beautiful valley. ‘I found Lucy had tea and a large blazing fire both of which I enjoyed.’31 Next day ‘a large assemblage of Bouriats’32 gathered. They had come to look at ‘such strange animals who had come from so distant a land’.33 Lucy found the men were more industrious than the Kazakhs ‘though not so gentlemanly-looking; whereas the women, some of them, were really pretty … probably owing to their not being so hard worked’. The night was very cold. Alatau called for water about midnight which proved full of ice – in June – and the next day snow ‘began to fall fast and soon covered everything’.

The Black Irkut

The Black and White Irkut rivers, south-west of Lake Baikal, join to form the Irkut, from which the city of Irkutsk takes its name. Thomas found ‘several striking scenes’ to sketch in the Black Irkut valley as well as precipices of limestone and beautiful white and yellow marble of the highest quality. At one point the ravine was filled with snow and ice, the tops of large poplars protruding – and in full leaf.

After several days they reached ‘Nouk-a-daban’, ‘a mountain up which it is possible to ride’ – but in their case only with difficulty because of the heavy rain and melting snow – and once more the horses sank ‘above their saddle-flaps’ in a morass. They were then enveloped by fog, dangerous because of the ‘tremendous precipices’ in the area, but when the fog lifted ‘a bright sunny morning with a clear blue sky … afforded a fine view of the Eastern Sayan’s highest peak’, Munku Sardyk (3,491 m, meaning ‘eternal snow and ice’, spelt Monko-Seran-Xardick by Thomas), which straddled the Russian–Chinese border. They descended by a pass and then a ravine where Thomas found a spectacular natural arch of limestone, which he depicted graphically in his first book.34 He had nearly finished his sketch when he was ‘startled by a rushing noise far above’ which lasted for two minutes, then suddenly stopped, succeeded a few moments later by ‘a terrible crash’: a great avalanche had plunged down the side of Munku Sardyk into a gorge.35

They spent the night at the mouth of the White Irkut – a mountain torrent ‘always white and foaming’ – and next morning Thomas and three men (perhaps Cossacks and a Buryat) began to ascend the Black Irkut, which joined it – ‘black as Erebus’ (considered Lucy); he sketched two fine views including picturesque shapes of the river, slate and limestone rocks and then walked up the bed of the White Irkut (impossible to ride up), impressed by the water rushing through a narrow chasm with perpendicular rocks up to a thousand feet overhead.

They descended into the valley of the Oka, northward-flowing tributary of the Angara, when the rain began cascading down, which made them glad to stop, but in their canvas dwelling ‘with the rain pouring in torrents outside’ (how often have we heard of those torrents already?) they were, however, not ‘the most miserable beings in existence’. With a frail shelter, Lucy tells us, from

a raging storm; with a cheerful blaze in front, appreciated the more on account of the difficulty we had in raising it; – and with a glass of hot tea, we thought ourselves superlatively happy, especially after what we had passed through: even the boy crept close to us, and looked with a pleased smile on the crackling logs.

Their destination now was the summit of a remote mountain top, 2,000 m or more high, in the Eastern Sayan west of Irkutsk. They knew that here atop Mount Botogol was an astonishingly rich deposit of pure graphite being developed by a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Alibert, who had been looking for gold in the area. He had not discovered this deposit himself but bought the rights three years earlier from a local Russian who had been told of it by a Buryat hunter.36 The Atkinsons ascended the dome-shaped mountain above the Oka river past a series of lakes and a deep morass (again) ‘where we were floundering in mud and water at every step we took’, but they ‘had crossed worse places; and we rather astounded our host [Alibert] when we told him’. The eighth child of a draper, Alibert had worked ‘from the age of fourteen in a London furriers’ which sent him at seventeen to Russia to hunt fox and ermine until gold-prospecting in Siberia took over.

Surprisingly, the visitors found all necessities in this inaccessible spot. Alibert had made a road down to the river and started a farm ten versts away to supply his workforce – followed later by a church and even hippodrome – so he had butter, cream and vegetables supplied daily (Lucy ‘never thought to have even a potato’). All this, considered Thomas, was ‘a work of great labour and expense and proves that He is no mean Engineer’.37 And ‘All the works which he has executed are far superior to anything I have seen in Siberia. Considering the work people he has to employ, I am greatly astonished to find all his plans so well carried out.’ Lucy indeed considered that they found everything they could desire except cleanliness, ‘the black lead [graphite] penetrating everything’. At least Alibert ‘had wisely built a bath, a very necessary precaution’, thought Lucy.

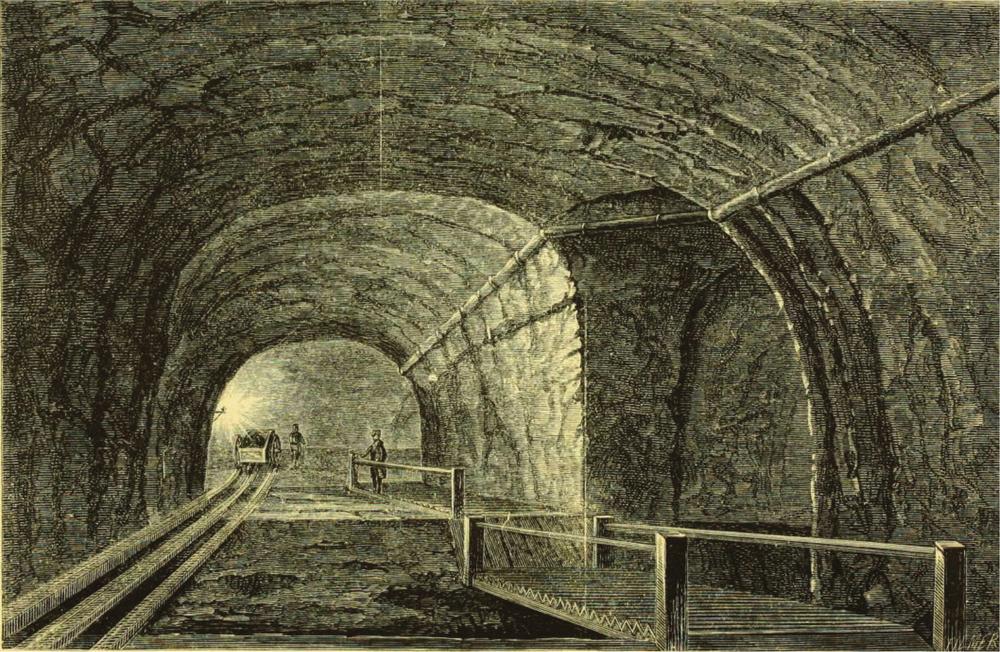

‘Principal gallery in the Alibert graphite mine’

Next morning it was ‘raining tremendously … every mountain was covered with clouds’ and three hours’ ride took them to the mine on the summit. Alibert took Thomas in but it was ‘so covered in ice that it was impossible to distinguish one mineral from another’. He showed Thomas ‘some beautiful specimens of Black Lead which as far as he could judge were quite pure’ and not as hard as Brookman’s pencils. (Thomas does not tell us what he was using himself.) Thomas was very impressed: everything had been done in the best way with no expense spared, plans ‘well considered and most scientifically executed’. He had, his journal records, ‘seen no Zavod or Priesk inside Siberia’ to equal it – or to equal his workmen, better fed and clothed than anywhere else he had seen. So, Thomas wrote, he hoped Alibert ‘will be successful and obtain a large return for the capital and time expended’.38 ‘Should this lead prove of a good quality … He may supply the pencils for the whole world for ages to come.’ It was only in his seventh year that Alibert had found graphite of even better quality than that of England’s Borrowdale, until then the best in the world, and he was to sign an exclusive contract with the German firm of Faber (now Faber Castell) which saw his pencils sold all over the planet.39

Alatau found it very difficult to move in the nearby morass, so Lucy says they ‘invested a little money’ in a pair of reindeer which they bought from apparently the only Samoyed family in the region – one of the Uralic-speaking peoples of Siberia – in this case probably the now extinct Sayan Samoyedes, living in conical, skin-covered tents.40 It was, however, a failure: after the very first day the saddle kept on getting twisted, and when ‘our man’ said it was difficult even for an adult to be comfortable on one, Alatau was thenceforth strapped on to a horse which he ‘rode very comfortably’, although he often got tired after riding too long and would fall asleep, when his parents took turns to carry him.

They rode on north-west through the East Sayan mountains to Okinskoi Karaul,41 a Russian border post on the Oka river. Thomas spent several days sketching in the river valley, ‘a most romantic spot’, he thought,42 and he produced a striking watercolour of the small Jom-Bolok river, tributary of the Oka, where it falls vertically over an ‘immense’ bed of lava apparently 86 ft thick with a large cavern behind the falling water. ‘It is dark, – almost black: indeed, the eye cannot penetrate its shade and depth.… The scene had a dreary aspect, but the colouring was exquisitely beautiful.’

Thomas was fascinated by the lava and determined to find the source, which he thought was somewhere in the Jom-Bolok river valley. He set off with two Cossacks and three Buryats, the latter doubtless with the greatest reluctance as Buryats dreaded the valley, avoiding it at all costs, badly scared of Shaitan’s (Satan’s) presence. Thomas was not surprised, as ‘a more savage and supernatural valley I never saw’, although Lucy found it ‘beautiful but singular’.

Next morning they found that the Jom-Bolok at times disappeared for ten or fifteen versts beneath the lava and then rushed out again. Sometimes they rode at the foot of high precipices along the edge of the lava, sometimes on its surface, but those deep fissures required great care. Lucy, however, insisted she had been trained in a rough school ‘and nothing would daunt me now’.

They dined in a beautiful spot with a waterfall and ‘our carpet was soon spread in a garden of roses and other flowers, and Alatau was quickly in among them gathering nosegays, for flowers are his delight; our hats and horses’ heads were always decked with fresh flowers when we were in their region’.

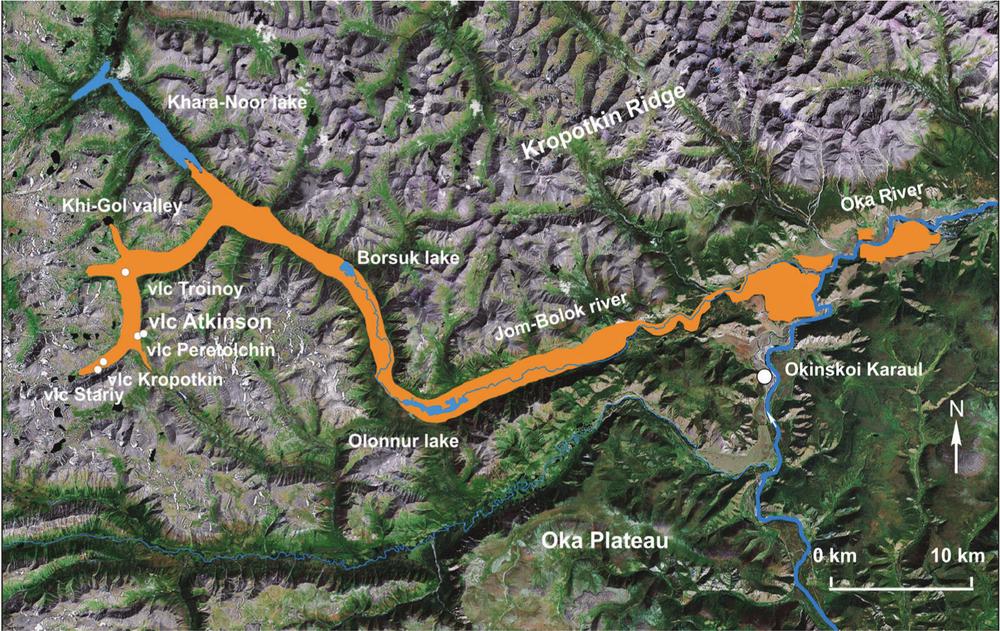

‘River Djem-a-louk [Jom-Bolok], Oriental Siberia’

Exploring the East Sayan mountains, south-west of Lake Baikal, the Atkinsons came across this river, whose course had been intermittently blocked by lava for some 70km. Here it flowed over the deep bed of lava originating from the volcanoes nearby, one of them now called the ‘Atkinson Volcano’, since he discovered it.

Still in the forest, they came on a ‘most wild and rugged scene; huge rocks … hurled on to the bed of lava from the precipice above’. When riding was impossible thanks to the deep chasms, Thomas set off on foot with some of the men, leaving the others with Lucy and ‘the boy’. They began to cross the lava – a difficult hour’s walk – ‘our boots being cut at every step to say nothing of the pain caused by the sharp points of the Lava’.43 (When they finally returned after four days their boots were cut to pieces.)

The lava had evidently flowed at a great speed as it was sometimes in mounds 50 or 60 feet high, over which they had to climb. It continued through the adjoining Khi-Gol valley along which they proceeded:

On turning a point of some high rocks I saw to my infinite delight a cone … we stood on its apex and looked down into its deep abiss … nothing but ashes and a redish pumis stone … so steep and the ashes so loose that if once at the bottom it would be almost impossible to ascend. I made a sketch from the summit looking south to another cone at about two versts distance [and] … we took up our quarters under some large masses of Lava one of which formed my bed on which to rest but not to sleep, as that was impossible.44

The Jom-Bolok river

The river (marked blue) is dammed intermittently for some 70km by the lava (marked orange) from the extinct volcanoes, including the Atkinson Volcano in the Khi-Gol valley. (After Arzhannikov et al., 2016, with minor modifications)

Thomas is officially credited in Russia today for having discovered this extinct volcano, which indeed is now called ‘Atkinson sopka’ (‘volcano’). He found two other cones that day, but it is now known that there are altogether ten in the area (of much interest to vulcanologists), which is today called the Valley of Volcanoes or the East Sayan Volcanic Field. The lava flow was extraordinary: it proved to be 70 km long, up to 4 m wide, and 150 m deep (five times Thomas’s estimate), with an astounding volume of 7.9 cubic km. It is now thought that Atkinson’s extinct volcano probably erupted twice, some time between 5,000 and 7,000 BC and then between AD 682 and 792, when Mongolian chronicles 400 years before the birth of Genghis Khan suggest that the Mongols witnessed an eruption and fled the area. His rather confusing watercolour of the crater (but not the cone) appears in his first book, and the Illustrated London News after his return to England published an impressive whole-page engraving of it; he produced a striking watercolour of the Khara-Noor lake, which almost certainly had formed when the lava had dammed the Jom-Bolok.

After their tiring but triumphant expedition, they returned to their base ‘quite exhausted by the intense heat which is refracted from the Black Lava’. On the way Thomas saw a sable for (surprisingly) the first time and soon despatched it. (What happened to the valuable fur, one wonders?) Their tent was scarcely up that night when ‘the Thunder began to bellow in the Mountains’ and the rain began to pour ‘down in Torrents which continued all night’.45 The following morning they rode off ‘in very heavy rain – all the small streams we had passed before … were now quite Torrents’ and they took shelter in a tent.46

After further exploration, they started back to the Oka, glad to find shelter in a Cossack home which, however, they agreed was worse than the storm because of the number of ‘screaming tiresome children’ and their terrible noise.

When the rain abated a little Thomas sought out a good place for their tent on the bank of the river, the level of which had risen greatly since they had crossed it only a few days earlier, and ‘there had been so much rain … that the Water was now most unusually high. I watched the rising of the Water with considerable interest … mark after mark was covered so quickly’ that they consulted the Cossacks and the oldest inhabitant who all thought it would not reach them as it had never been so high before.

It was however thought prudent to have a Watchman…. Soon after dark we turned into bed and I felt convinced we should have to move ere morning [and] one of our cossacks fixed upon a place higher on the Bank for our Tent should we have to Move in the Night. It is no pleasant feeling laying down to sleep near such a roaring Flood as this was now. I was kept long awake by its noise.47

At three oclock the Bouriat called me and ran to tell the Cossacks the water was now at the Mark we had fixed and was rising fast…. Lucy was up with Alatou [fast asleep in her arms in the still pouring rain] and our canvass home was removed to a much higher point than the one selected last night…. At 7 oclock I found the Water had risen three feet and all the little islands were now covered. All chance of our crossing the River was now at an end untill the Water subsided. There was no help for us, only to wait with patience, but when we should be able was extremely doubtfull…. About 3 oclock I saw one of the two Boats carried away by the flood, and the other was tied fast to a Larch tree [formerly on the bank] which stood now near the centre of the River, with no means of getting at it as all would be swept away that attempted [it]. The water had now reached the place selected for our Tent. Fortunately I had decided to be higher up on the Bank.48

To Lucy ‘what was most remarkable was the incredible number of large trees that were swept past … I never saw such a sight’. Later they came across some grief-stricken Buryats: the flood had ‘swept away two of their dwellings, women, children, and all; it was heartrending to hear them wailing for them’. No one ‘remembered such a flood’. On waking the third day, they found a clear, bright sky and the water level had fallen a lot. The goats and lambs frisked about and greatly delighted Alatau, who loved all animals. He much amused the Cossacks and Buryats by filling his pockets, unnoticed, with bark (used for lighting fires) and producing it when required.

On 24 July they prepared to cross the river, a slow process as only one person at a time could be paddled across. Before they left Lucy wanted to thank a Cossack’s wife who had done the Atkinsons several kindnesses, including making bread for them. Lucy tried hard to offer her some money, but in vain, and after some hesitation she told Lucy ‘the greatest kindness’ she could do her, ‘if she dared’ ask it, would be to give her a tumbler so that when the priest visited them (which he did a few times a year) she would be able to offer him tea – and he was expected soon. Lucy acceded, adding a few other items, and ‘left her the happiest woman in the place’ with its only tumbler.

They slept that night in a Buryat aul, finding in one yurt ‘a very pretty black-eyed young woman, with cheeks like roses … of a delicate tint … in a closely fitting black velvet jacket, which became her amazingly’, and her head ornamented. The Atkinsons were intrigued to find in the yurt ‘a picture of their [lamaist] deity, very nicely painted on silk’ and in all yurts an altar bearing several brass cups filled with offerings: ‘butter, tea, coffee, milk and sugar’ and ‘a strong spirit made from milk’ which they drank a lot.

Reaching the Oka again, they found it too flooded and rapid to cross and realised they had to take a mountain route, which was both difficult and dangerous because of the rain. At the summit there was only a morass ‘which was positively frightful; the men had several times to get off their horses to drag them out of the deep mire’ through which they had to wade for hours and they were forced to encamp after a tiring ten-hour ride on the only dry spot they could find – blocks of granite on the side of a steep hill with ‘not a single level spot’ – so Lucy found it very difficult to spread their bearskins. She looked forward to a bed of down to compensate for all that her ‘poor bones’ had endured; ‘at times they are really sore, as if I had been beaten’. (In the next town, she regarded her bed, ‘nothing but the bare boards of a bedstead covered with my bearskins, as a perfect luxury’.)

‘Bouriat temple and Lake Ikeougoune’

The Buryat people who settled around Lake Baikal built this small Buddhist temple by the edge of Lake Ikeogun, held in great reverence by the Kalkas. Here they would sacrifice milk, butter and animal fat, which they burned on small altars.

Their next hazard was sand hills near another river, and Lucy thought it would be impossible to keep her seat. One of the Buryats fell, making the others laugh. But in the only place possible to climb the far river bank was ‘a deep hole filled with mud, sand, [and] water’ into which the horses’ hind legs sank ‘deep and they plunged awfully’, spattering them all with mud. Lucy was ‘highly flattered when Thomas said, “However you keep your saddle I cannot understand”. It would never have done to have been unhorsed after this.’

Their track onwards was along the now ‘very pleasing’ Oka valley, and one night they stayed again in a Buryat aul, of which Lucy wrote, ‘You should see my son amongst them, dancing Bouriat dances; he has also learned one of their native songs, which he and a Cossack sing together, to the great delight of the Bouriats.’ They dreaded crossing the mountain of Nuhu-Daban as it seemed ‘almost impassable’ after the long downpour. But ‘Providence … guided our steps; otherwise it might have been our last ride’ as they were in a dense fog and could not see a yard ahead.

Further on they stopped at a Buryat temple filled with offerings of coloured silks hanging from the ceiling and banners hanging from grotesque heads. They greatly regretted not seeing any service and would have liked to hear the chanting and the cymbals, trumpets, bells and ‘immense sliding trumpet’, but the principal Lama ‘was so drunk [Lucy’s italics] that he could not officiate’.

They rode on to Lake Baikal by

another atrocious road … a sea of mud … the floods had made great ravages all over the country. Not a bridge was left standing and the Roads near the River have been swept away … we found people engaged seeking Lapis Lazule which is often brought by a flood. One Woman told Lucy she and her husband had found 12 lb. which they sell to the Bouriats for seven roubles per lb.49

They had to wait two days at Kultuk on Baikal’s south-west coast while a boat was prepared for them. The first night, in the house of the village headman, Lucy could not close her eyes as it was a repeat of the night spent plagued by a mass of insects in the Altai. Next morning when the headman asked about their night Lucy ‘complained bitterly to him about the insects’ and said she would now sleep in the boat, but he advised them to sleep ‘in the flour magazine’ which they did the next night and, having missed so much sleep, slept soundly till dawn. When their host now enquired how they had slept, he said he hoped the rats had not disturbed them unduly and Lucy ‘almost shrieked’ and asked if there really were rats. ‘Oh yes,’ he said, and told them that he sometimes slept there in the summer as being cool and ‘they annoy me very much, but I thought perhaps you would not mind it.’

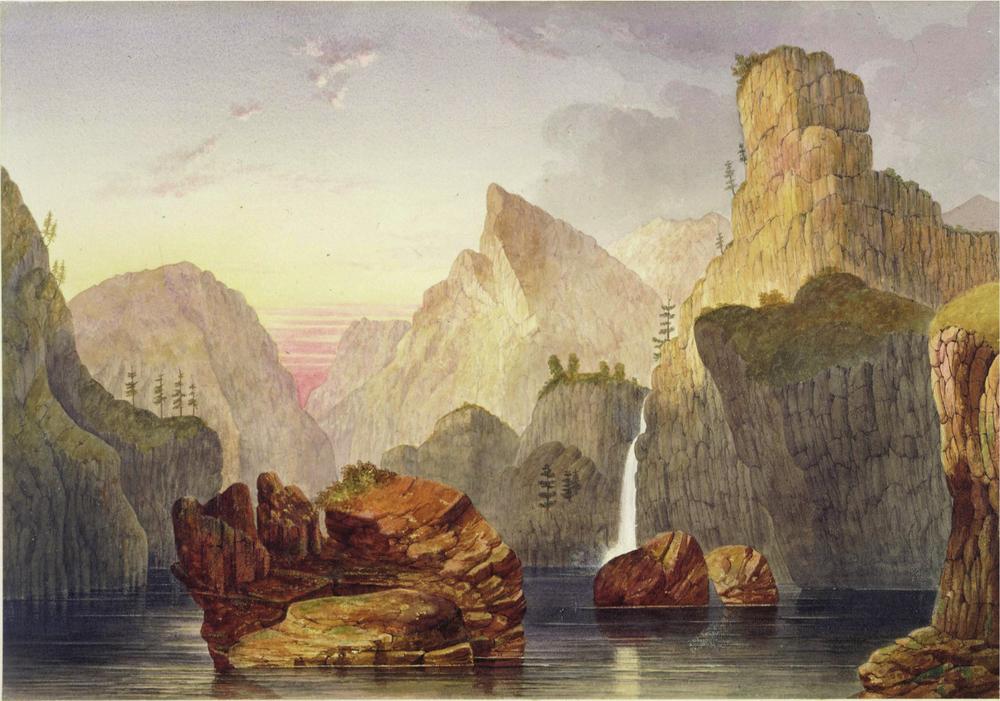

‘A natural arch on the Baikal’

Thomas claimed that there was little to paint at Lake Baikal, although he produced several sketches including this one which he published in his first book. This arch was apparently much smaller in reality, here exaggerated. Lucy is portrayed sitting on the rock in the hat that appears in other paintings, so if Thomas omits her from print, he appreciates her at least in paint.

As for Baikal, by far the deepest and oldest lake50 in the world (though this was not known at the time), the Atkinsons were both disappointed, Thomas ‘greatly’ so, according to his journal where he stated that there was nothing either grand or picturesque on the shores. But that verdict was after only one day and one sketch.51 Lucy however thought Baikal was certainly well worth seeing, although not for an artist unless visited before Altin-Kul. Thomas relegated only the last two and a half pages of his 598-page first book to Baikal even though, he says, he spent twenty-eight days on it.52 And his second book gives it less than a chapter, although he concedes that ‘a picture of extraordinary beauty and grandeur’ was provided by the four-mile rapids past the great, sacred – and supposedly miraculous – Shaman rock: the Angara’s outflow on the west coast from Baikal, the only river flowing out of the lake compared to the 300 and more flowing in.53

But if the great lake did not appeal, the storms did. Heaven knows the Atkinsons had experienced enough already, but Lucy thought the storms on Baikal were ‘very fine’ and that it ‘was magnificent to remark the changes that came over the lake.’54 At one moment, Lucy writes, the Atkinsons

would be looking at it when it was as clear as crystal, and revealing everything within; the rocks at the bottom discernable at a great depth, and on them at times even the little fish lying dead; when suddenly a storm would rise, entirely changing its aspect, heaving it into billows, and hiding everything from view.

They embarked along the lake with four rowers and a helmsman, stopped for the night – to be almost eaten by mosquitoes – and next day ‘turned out at dawn’ (as so often) along the coast of ‘the same Monotonous character’, thought Thomas, mostly cliffs. ‘At 8 oclock we got to Listvenitza [then Listvenichnoye but now Listvyanka, a village on the west coast]’, just beyond the Angara, ‘our men completely done up’ – not surprisingly if they had been rowing all day, and next day ‘our old men would go no further’.55

Because of the many violent storms on the lake, which sank many boats, two steamers (or at least their engines, boilers and machinery) made in St Petersburg had arrived by land in the 1840s for the important west–east crossing, with the hulls built at Baikal by peasants under supervision. The Atkinsons hoped that the ships’ ‘director’ could give them new rowers, but as he would not return till late at night they settled into the steamboat house. ‘A Strong gale sprang up and tossed the Baikal into waves like a sea – we sat on the Shore and enjoyed a scene which called to mind the scenes of our youth,’56 although Thomas’s childhood was spent far from the sea.

Next morning the smaller steamer of the two was at the pier, and it was agreed that if the Atkinsons could wait for two days it could take them to Goloustnoye, a village further up the west coast, ‘as it would only be ten versts out of her course’. They drank tea with the director of the little pier and his mother – ‘I cannot say much either in favour of their Manners or Hospitality’ (underlining by Thomas).57 ‘Again we had a strong gale with rain in the Evening’ and ‘in the night the rain poured down in torrents. What a country for wind, rain, and fog’ and the director (who now turned out to be very civil and was to give them a free passage) told them that ‘in June and July the fogs are so great that you cannot see 20 paces’.58

They ‘turned out’ at 4 o’clock next morning – even earlier than usual – and sailed at 8.30. The captain, they found, was an elderly Swede who, to mutual delight, spoke English, having served in the Royal Navy. He had been eight years on the lake, ‘sometimes as smooth as glass, at other times in fearful storms’, and told them that when one particular wind blew from the mountains (he must have meant through the Sarma valley on to the lake, Baikal’s strongest wind) he said the lake was ‘then very savage’ (underlining by Thomas) and navigation very difficult. Baikal’s great depth was unknown at that time, but the captain found some parts very shallow and others unfathomable, finding no bottom with 200 fathoms of cable.

‘Baikal, Oriental Siberia’

After the captain dropped them off they were rowed up the coast and round a headland and that night slept under a large boat they found on the shore.59 Next day Thomas, up with the dawn, found ‘the effect of the coming day was exceedingly beautiful.… From this point Eastward nothing but water is seen, and the Sun rose up like a great Ball of fire quite red by the Haze from the Water.’ They set off again by boat and after twelve hours reached ‘a very pretty bit of rock scenery’ which he sketched and had just finished when a dense fog materialised, making everything invisible beyond twenty paces (as they had already been warned) and, though it cleared a little later, ‘the waves rolled in with great fury’.60 There followed several days of bad weather – calm interspersed with violent gales – which made it dangerous to continue their voyage.

Fortunately, Saturday morning before daybreak at least was ‘nearly calm’. They returned to their boat, and soon a strong breeze blew up which drove them on to rocks twice – the second time ‘truly dangerous and I expected every moment the boat would be dashed to pieces…. At last we succeeded in getting the boat off’61 and the Buryat boatmen kept the boat upright but almost drove Lucy crazy with their singing. However, ‘they seemed so perfectly happy that I had not courage to ask them to cease their Baa-a-a-a-a!’

Two hours later the Kultuk wind began to blow – fortunately in their favour – and they began again despite the rough sea and ‘a great deal of water … pouring in, but we could keep it under by baling’. Having made five further sketches that day and the next, one of them of Baikal’s largest island Olkhon, Thomas confirmed his first impression: ‘there is really no fine scenery on this lake. There are some fine Rocks but such a sameness’,62 although he believes that some parts ‘would be highly interesting to the Geologist’, and his journal for 1851 ends here, although confusingly he uses some of the blank pages for his travels in the following year (1852) and after that a list of his 1851 sketches.63

That last night at Baikal they slept at a widow’s cottage in Listvenitza on the west coast, and heard that her husband had been a fisherman who had drowned in a storm. His colleagues had spotted him in the astonishingly clear water lying at the bottom of the lake – granted not a deep section – as if asleep. Several times the Atkinsons ‘had a chance of lying at the bottom themselves, especially when the wind suddenly rushes down the valleys, when it catches the frail boat, and nearly capsizes it’, as Lucy wrote.

Back to Irkutsk and then they made ‘a little journey’ (by their standards: only some 500 km) on to the river ‘Hook’ (perhaps Uk) near Verkhneudinsk for Thomas to sketch a waterfall for an Irkutsk resident. He and the archbishop considered this fall ‘finer than the Falls of Niagara’ but Lucy dismissed it as ‘a trumpery thing’ which Alatau could have jumped over when a little bigger. They slept several nights in their carriage on the way and they and their Cossack coachman were asleep after a change of horses when Lucy was woken ‘by a heavy hand’ on her face. She said to Thomas ‘Your hand hurts me’, and dozed off again. At the next station she found that her bag had gone. It contained both copper and silver coins and she always kept it behind her head as she was ‘paymaster’ and could find it immediately. The bag was ‘a sad loss’, as apart from the two bags of money there were a lot of other things: Thomas’s telescope, earrings and beads as presents, Alatau’s socks and shoes, a tiny pocket bible (given to Lucy), bags of dried fruit for ‘the child’ and a host of other items. They informed the police but heard nothing from them ‘nor ever will’, thought Lucy, who learned that there were many robberies at that station – even from the Governor’s carriage. But Lucy noted that all this was nothing compared to Thomas ‘having taken cold, and being confined to his bed for fifteen days’. Another bout of illness for him, but why fifteen days for a cold? Was his health deteriorating?

On their way to the waterfall at Verkhneudinsk, they stopped at a salt zavod where there seemed to be no security, although all the workers were convicts. And the room where Lucy slept had no bolt or lock despite the fact that the maid relegated to her and sleeping in the next room had murdered her master (Lucy’s italics) and the children’s maid had poisoned her mistress. Their hostess told her that when she arrived years earlier she was really scared of being murdered, but now she maintained ‘they are the best servants she ever had; she prefers them to any other’ and most of them ‘had been driven to commit crime by the brutal conduct of their masters’. But Lucy stresses that all this was by no means typical in Russia, although some crimes were certainly extreme, and once the Atkinsons went to see one convict in chains guarded by Cossacks who had confessed to seventy (her italics) murders, had escaped and was awaiting trial with, surprisingly, ‘an exceedingly pleasing and mild face’.

They returned to Irkutsk where in November Alatau celebrated his third birthday with a ball to which

all his little companions were invited … right merrily have they enjoyed themselves: such romps, and dancing too; the musician being a musical box. I gave them a surprise at supper, viz. a Christmas pudding. How the little eyes were dilated when they saw it come flaming into the room! … the first plum-pudding ever made in Irkoutsk.

The next day many people came for a taste (Lucy’s italics) ‘and all regretted they had not seen the grand sight’.64

According to Lucy, Alatau had cost her nothing for clothes except for one piece of silk bought in Kopal. All she needed to buy were shoes and socks from St Petersburg. In Barnaul she was ‘loaded with material for dresses’, some in Russian peasant style, and a friend, S. from St Petersburg (probably Sofia, her previous charge), sent many more dresses, while another was a present from the wife of the civil governor’s wife, Madame Zarina, of ‘most beautiful’ thick pink Chinese silk trimmed with silver lace and buttons which the boy wore with a black velvet cap (also a present), being ‘greatly complimented on his appearance.… My son is a most fashionable young gentleman.’

At the beginning of 1852 there was ‘no end of balls and evening parties’, but the far weightier matter was the possible amnesty for the Decembrist exiles, who had been ‘in a great state of excitement’ for the two previous months. They fervently hoped, indeed believed, that the twenty-fifth anniversary of Nicholas I’s accession would mark ‘their liberation from exile’. But the day of accession came and went and then a fortnight passed which could have brought a courier from St Petersburg. ‘They were forced to abandon the last hope.’65

Then a mounted Cossack arrived in haste – at last! – but no, he had come because of the escape of a young Polish exile whom the Atkinsons knew – ‘no more than twenty years and of noble extraction’. He had not reported as he should have done from the village he had legitimately visited and had somehow procured a merchant’s passport, knowing that the Tsar’s pardon was not forthcoming. Cossacks were sent in all directions, but it was the postal officials who stopped him and he was imprisoned in Omsk. His fellow exiles all declared, Lucy noted, that if they had considered escaping they ‘would never have been taken alive’ as punishment would start with ‘public flagellation in the town from whence he had fled, and then banishment to the mines for life, with no hope of release’.

But, against all expectations, it proved to be true that he had escaped from prison and, it was thought, would have tried to reach the Kazakh steppe but, if the Kazakhs took him prisoner, the Atkinsons knew they would sell him as a slave or, like a Russian prisoner of the Kazakhs they had once seen, insert a horsehair into his heel, which would lame him for life and turn him into a cow-herd.

Thomas and Lucy were looking forward to their visit to Kyakhta, south-east of Baikal on the border of Outer Mongolia, then part of the Chinese Empire. Lucy was glad to leave before the carnival time of Maslenitsa as she was tired by the number of balls in Irkutsk, particularly the preparation for them. She was going to one ball in a dress she had worn before when two young friends – and Thomas in support – ‘made such a fuss … that I was forced to go out and buy a new one’, and ‘scarcely a week passes without a ball or an evening party’, not to mention plays. When the Atkinsons took a box for the opening play of the season Alatau ‘made his début’ among the audience; the only child there, ‘he was in ecstasies, and applauded as loudly as he could’. His appearance set a fashion, for the next time Lucy went it ‘was crowded with children’.

Almost every Sunday in Irkutsk the Atkinsons would dine with the mayor of Irkutsk, Mr Basnin (with whom they had left their belongings temporarily), a very clever merchant with a collection of ‘valuable Chinese ornaments … a splendid library, besides extensive hot houses’ on which he spent great sums buying plants, yet knew nothing about them, and none of his family had ‘any real love for flowers’. But he enjoyed simply walking through his hothouses after dinner, smoking his cigar. Fortunately he had a friend with not much money who did love plants and was only too pleased to be in charge of them, and it amused Lucy and Thomas to see the mayor ‘asking permission to cut his own flowers, or even to gather a strawberry’.

The Atkinsons set off for Kyakhta in early February: ‘a visit of pleasure’, considered Lucy. They started at 2 a.m. in order to cross Lake Baikal by day. The fifty-five versts took them four hours to complete in a keen wind and temperature well below freezing. Fortunately General Muravyov had lent them his warm and comfortable sledge, but despite being wrapped in furs Lucy found it difficult to keep warm and had to have her feet rubbed often. Yet Alatau was so warm, he claimed, that he ‘threw off his furs and sat for a while with his arms naked’ even though ‘the poor horses were bleeding at the nose’, and the yamshchik had often to rub them with snow and sometimes run alongside to keep from freezing himself. The view was ‘one dreary snow-white waste’ with waves of ice frozen as they rose.

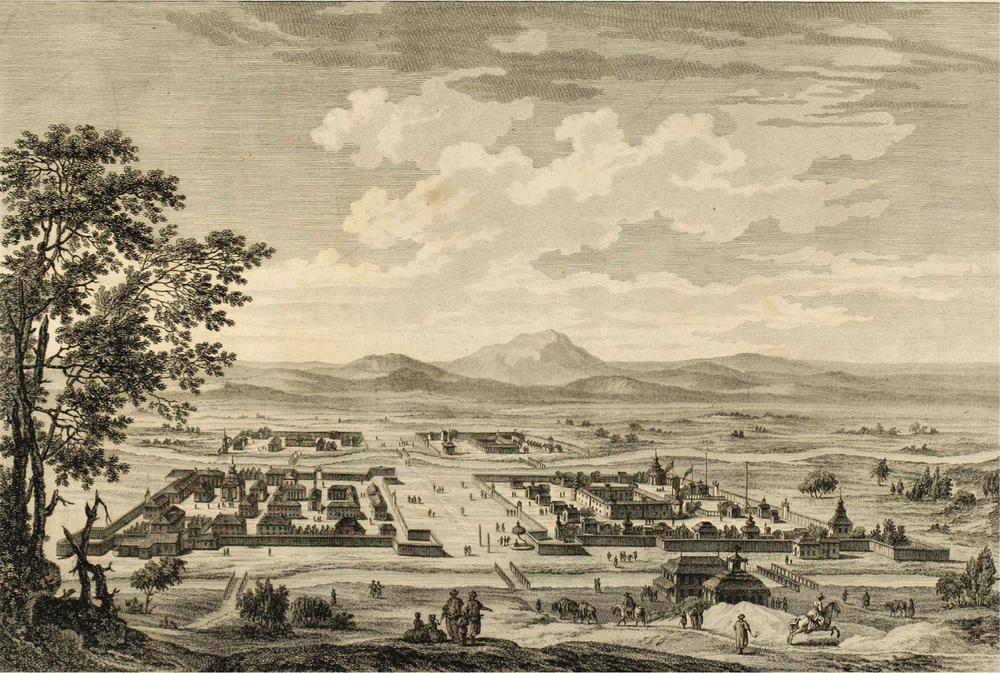

Kyakhta, Russian and Chinese trading towns, separated by neutral ground

On the Siberian–Mongolian border between the Russian and Chinese Empires, Kyakhta was the most important trading post between the two, dealing in huge quantities of, above all, tea and cottons from China and furs from Russia. Town view, printed in Paris, 1783.

Once across the lake they continued through the beautiful scenery along the Selenga, Baikal’s greatest tributary of all 300 or so. The hoar-frosted trees sparkled ‘like diamonds and rubies’ and they stopped four versts before the important Russian–Chinese trading centre of Kyakhta at Troitska, short for Troitskosavsk, its administrative centre, where they were to stay with the Director of Customs.

Cross-border trade here had begun in 1727, and a few hundred yards south of Kyakhta just across the border was the complementary Chinese trading town of Maimachen (meaning ‘buy–sell town’, today Altanbulag). Its dzarguchei or governor gave the visitors a hearty welcome and they dined with him one day and supped with him another (and asked for chopsticks). They ate off plates the size of saucers with a choice of twenty dishes – the first course boiled, the second stewed, the third roast and finally a choice of ‘delicious’ soups. One Chinese meanwhile looked after Alatau and before the end of the meal the dzarguchei ‘politely excused himself, and went to have a game with the child … rolling about on the sofa, he quite as delighted as the boy’.

The Atkinsons found Maimachen a town with a temple, a court of justice and a small theatre with very narrow streets where small one-storeyed wooden houses were set round courtyards. Flags and coloured lanterns ‘stretched across the streets’ in the evenings. The shops – where no goods were displayed but all kept in cupboards – seemed spotlessly clean and tidy (though no Chinese women were allowed). Dealings, still by barter, between the two towns took place only between sunrise and sunset when Maimachen’s gates were locked with a ‘ponderous’ key. Basically only the merchants trading with China were allowed to stay in Kyakhta, some of them very rich agents for Russian concerns. All others, including the Atkinsons, had to stay at Troitska, both the administrative headquarters and the site of the customs house where all Russian and Chinese goods had to be deposited before being bartered (although money was starting to take over). By now Maimachen was ‘the only town whence Russia has obtained her tea’, as Thomas says.

The Chinese goods arrived by camel caravan across the Gobi desert and the Mongol steppes: cottons, silk, 300,000 lbs a year of dried rhubarb,66 but above all tea – ‘much in the form of hand-packed bricks … which even served for a time as units of currency’ in Kyakhta. Half a century before (in 1800) the better-quality loose tea arriving through Kyakhta had already risen to nearly 700 tons a year (compared to 567 tons of brick tea), nearly 2 million roubles’ worth. (The tea the Atkinsons had been drinking had probably all come from Kyakhta.) In return Russia was sending to China millions of good-quality fur pelts, particularly Siberian squirrel (the sable had already been decimated) and began to turn to the beaver of North-West America which reached Kyakhta in its tens of thousands. It was no wonder that this small town became known as ‘the village of millionaires’ and could boast a stone cathedral as well as a museum.

Count Nikolai Muravyov-Amursky

A relative of both Lucy’s former employer in St Petersburg and of the exiled Muravyov Decembrist, this General Muravyov was the incorruptible Governor-General of East Siberia based in Irkutsk and lent the Atkinsons a warm sledge to cross Baikal in winter.

On their way back to Irkutsk the three Atkinsons stopped at the settlement of Selenginsk on the Selenga river (now known as Novoselenginsk), where three British missionaries had tried (unsuccessfully) to convert the Buryats to Christianity earlier that century. The Bestuzhev family lived here, with whom Lucy was ‘perfectly charmed’. The two brothers, Nikolai and Alexander, who had both served in the British Navy, were Decembrist exiles and had been joined by their three sisters, who were not allowed to return, the eldest of whom reigned like a benevolent major-domo, treating her siblings like children. Indeed, she called her younger twin sisters ‘the children’.

She took Lucy to see the farm her brothers had started, showing her ‘the cow-house, fowl-yard, stables and coach house’. Her younger brother, Alexander, had indeed taken up coach-building, of which she was very proud. She told Lucy she wanted him to marry and wished she would give him some advice. Lucy was then shown the ice-cellar with an adjoining room as a dairy, and then in this sister’s ‘private apartment’ heard the sad story of their mother, who had applied several times to the Tsar for permission to join her sons. Her hopes rose and fell over time and at last permission was granted. They immediately sold their ‘house, furniture, horses and carriages’, said goodbye to their friends and set off to Moscow only to find there an ukaz or official order cancelling the permission, with no reasons given. The greatly shocked and saddened mother appealed to the Tsar again, but ‘after weary waiting’ her longing to see ‘her beloved sons’ affected her so much that she died just as permission was finally received a second time.