The carpenter’s sleeping hand did not fumble, floating over his frail dreaming wife, without disturbance, to smother the almost waking clock: with the certainty of an auctioneer. Four-thirty in the morning. Nothing yet moves in the street outside. It is past death’s last visit and before the shudder of birds. He gains balance and slides out from his side of the bed. Reinforced by a board beneath it, intended to straighten his back, the bed is as hard and as stiff as his liver. In advance of a broken hip and in retrospect of a fractured heart.

So this is how the day begins. Quietly moving in the bedroom and kitchen. Carrying his shoes to the street door, steadying the tilt of furled sleep with a tot of rum, before leaving. The weight of the drink’s thick darkness inverting the hourglass of this new day.

The house is set in a long road of homes, each one alike, each painted to be different. It is north of the centre, so he follows gravity, down, to his work. But that is hours away; first he must establish his territory and his communion, turning the mechanisms of unseeing into his favour. He must begin the outward process of being seen by choice, seen by his workmates and overseers, even when he is not there. He must be unseen by ghosts. The inward chemical part is the exchange of blood for alcohol. This frost-covered morning was not the beginning of something, but just a moment in the continuous cycle, in which he kept absence in balance by dissolving identity.

London is a city that sleeps too much. This is the mould of its quality. A magnetic contract: to reinvent itself on the other side of dream, each day. And such dreams, smouldering against the tidal spine of the river, telling and retelling the tales that must be told to manifest a city’s bones. Whispering the night architecture back into stone. Millions agree to follow the sun’s pendulum, until their unconsciousness coalesces to a pure pulse that shadows the Thames. On a clear cold empty time like this youcan hear them all sleeping. The cold has drawn a membrane and a cone to collect their occulted labours, focused to a splinter of ice that inscribes submerged voices on hissing tracks, invisible but firmly held to certain known places, especially bridges.

There is no fake continuity here, no driven constant enforced by an over-stoked engine; nothing runs on fear-shifts terrified of pause. It is structured by memories and the little fluids that trickle between them. There is none of that adolescent pretence of younger cities; those that ‘never sleep’. Trying to convince the night that it is transparent to human desire, undreaming, matter of fact and ultimately tired. A braggart of awareness speckled with the lint of its cot. The blunt will of continuance believing it is cheating night, avoiding its depths and charging the city with power – when, in fact, the opposite is true. Drained and singing loudly to deafen out the faint but perpetual scratching at its virgin seams. The night workers in this city stay concealed. Hidden in locked buildings or toiling underground. Separate beings made more invisible when they leave their hidden labours.

The carpenter moves quickly for one so unfocused. The surrounding streets are no more than cardboard; disinterested sets painted in uniform colours. He never looks into the identities of the passing places, he never sees their unchanging – but feels it with an unspoken agreement of veracities. His crossings are no more than the elaborate fake journeys of his best-remembered childhood. Where, at Christmas, on a long-awaited visit to Santa Claus in one of the city’s vast department stores, he was bought a ticket to a dream voyage. He would sit with six or seven other children in a wooden box, while a painted landscape on a canvas roll was wound past the windows and the box gentle-rattled in a pretence of motion. Something of the wonder of these shabby exciting illusions stayed with him. Something of their obvious artificiality was convincing and drove a wedge between himself and the agreed painted roll of reality, for ever. So that now, in the bleakest of streets, the act of movement was liberating and modestly audacious. He enjoyed his grim ritual, which would soon be rewarded by the warm sweet doze of oblivion. All drunks understand the righteousness of compensation, and the satisfaction of its achievement.

It was only the few doubtful others he met on his way that jilted his momentum; only the ones that met the gaze he was not giving. Those we would become, trying to cup the moisture of recognition from his passing eyes.

His relationship with ghosts paralleled his attitude to work; the balance of labour and freedom, individual choice and purchased employment, their time and his. The ancient craft of skiving. Of being there when youare not, or being elsewhere all of the time. Clocking into a system that was so common that it was not there at all. The art of detachment, liberty taken in small, irregular gasps. Powered by cunning and agreement. Tiny wilful fractures in the daily chain of earning.

The carpenter worked in the Law Courts. A village system of jurisprudence at the heart of the city. A microcosm hungrily copied throughout the world: antique, venerable, formal, layered and conservative. An intricate hierarchy structured on class and attainment, position and power – with the dignity, pomp and fairness of the armed forces, Oxbridge colleges and other efficient and unquestioning treadmills.

The courts were divided into various houses, halls and chambers. In them, the higher echelons of law workers performed their daily tasks, breeding and dividing conflict with razor-sharp pens. A regiment of administrators controlled the buildings, the flow of paper and other eddies of communication. Making sure that daily trivia did not impinge on the sacred motors. Below them were the crafts-men, messengers, butlers, maids, kitchen staff, cleaners and other general foragers and carriers and sweepers that kept everything turning and stable. They lived in the arteries that duplicated the corridors and halls. A lymphatic shadow system that scurried unseen and close to the blood. Many of the workshops and storerooms were underground or hidden in tightly folded courtyards; appendices that most never found or knew to exist.

The whole edifice was riddled with ghosts. So much friction of emotion braced into control and rubbed hard on the membrane of corporality. To which is added the concentration of meaning: for many of these termite workers, the Inns were their only life. A trusted existence safe from the outside world. Which always proved to be unstable, female and slippery. The constant solidity of the Inns gave a firm ground and a clear horizon. Uncluttered by the uninitiated flapping of families and other random systems. The binding principle was the regular and unspoken flow of alcohol. It drained, fountained and circulated through the entire village, from the Lords to the Boot Boys, giving a common wavering anatomy to all of them. Omnipotence that lifted and divided time. Brightening the middle and the end of each day – and, for some, the beginnings too.

The carpenter drank to suppress ghosts, to blind them from his day and the concealed part of his thoughts, which most assumed he never had. Sensibilities that over the years had become inconvenient or a source of argument. He was now without sexual drive, ambition or what is usually described as ‘imagination’. These things had wilted, their pains and innocence soothed closed by the distant saintly smirk of drink, comforting and reducing the nagging sugars of humanity. This was part of the price of his conversion to transparency. The complex hungers of rich emotions sit heavily in the whilsting frame, that part of us that walks between flesh and spirit. That part of him that allowed the sanctum of hollowness.

Care must be taken where proximity grows. And yet he chose to wend his difficult path, leaving and returning through some of the most infested parts of the city. The old tenting grounds where markets grew before homes and businesses. He mapped his stagger between their haunted industry of passing, their saturated history of exchange. Markets that trade before first light, running meat, fruit, fish, flowers and grain to the core, while the rest of the city sleeps. Each market has its own pub or inn, bolted down to a different time, cutting no slack for this moment. Forever enacting the past in the future with little consideration for the present. Under the muscle of need, licensing laws and drinking times are barged aside, reverting to earlier frames, holding the ghosts that curl and bristle among the fog silhouettes of blur-men carrying grain, potatoes and oxen, or seriously drinking themselves towards midday.

St Bartholomew’s is his first call. The market pub is swollen full of men, the temperature steams out against the cold breath of morning. A red boot bar where coffee and rum lace the tobacco smoke and the newly mowed smell of open carcasses. Although the conversation is loud and active, some drinkers just stare into the surface of their shimmering beer. All are regulars, all are known and some are not alive. Occasionally there are eddies of smaller tighter men, finishing shifts from the hospital across the square. Smithfield Market and St Bartholomew’s Hospital have shared this tilted field for hundreds of years. The conjoined sewers beneath them are congealed with the blood of men and beasts. This swollen acre was once a festive home for execution, music, butchery, medical vision and debauchery; the wild joy of each element humped together, formally, in the ancient ruse of a three-day fair. The echoes of which can still be heard in voiceless shivers.

There is never conversation among the professional drinkers. Nods and minor gestures waft at shaggy recognition. By some reflex twitch of nerve, a drink is ferried from one drinker to another, by a barman who is more absent than any of them; it will be returned later on another calling. Other markets are shuffled into the carpenter’s circuits. Leadenhall, Spitalfields, Covent Garden, Billingsgate sometimes distort his daily track. Today it is the Garden; the wet sun is lamely sucking at the colours of the bundled flowers and the earth smell of vegetables. Stems and leaves are slippery underfoot and he tiptoes carefully into the public bar, its heavy doors loud and levering against the day.

He is beginning to find equilibrium as he walks on, into the fiercely treed enclosure of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Smoke is rising from the burning cardboard homes. A daily ritual, the homeless destroying their previous night’s shelter. Some of these constructions are elaborate, ingeniously crafted against the wind and frost. A collection of insulations and buffers: Adam’s House in Paradise.

He walks through the empty bandstand, its positive structure giving sound to his presence. He does this every day – and, at the same point in the circular stage, a memory uncoils and flickers in the enclosed darkness of his skull: like a whisper of a spring set in a quivering pulse; a tiny wire maquette of a galaxy stretching one of its spiral arms. The memory is of the ocean, swollen, vast and disconnected. Something like water and wood fusing in a death or a blessing.

In one of his lunchtime sessions, in his usual corner of a pub in Chancery Lane (long since gone, having, over centuries, transformed from coffee house to pub, and now back into coffee house again), he overhears a conversation about cork. The pithy cuttings that seal valuable fluids. He recognized the speaker, having once or twice attempted communication with him, as a regular who was always talking. A person normally to be avoided or seen through. But now, for no reason at all, he was becoming hooked and entangled with the words. The talker was conjuring the impossible in a thick Polish accent. He speaks of the object: a model of a tomb crafted in cork, weighing nothing, its maker unknown.

The carpenter follows the talker across the square to the Soane Museum. It is one of three secret spaces that hide in the lofty houses that fringe the park. He knew of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. He sometimes drank with one of the porters. He had seen its delicacies of pathology, its twisted stumps of folk, its malign cradles of glass and alcohol. He had seen the book bound in human skin and the Sicilian dwarf scurrying under the shadow of the Irish giant. But mostly he has seen the Evelyn tables. Four vertical slabs of wood saturated in a dark treacle of varnish, encrusting the root like tracery that is forever glued to its surface. Remains of men. Nerve trees and arterial ladders pinned down for inspection, the rest of the carcass cut away, its density of purpose disposed. These whittled human drawings chilled and excited him in a way that he could never explain. When once being questioned, after staying with them too long, he gave the easy answer: ‘I am a carpenter.’

And now, in balance, another wooden artefact had stolen his attention.

The cork models sit in the sunken darkness of the museum’s subconscious, near an over-tanked sarcophagus, at the far end of the underground room. They are scaled constructions of Punic burial chambers. Boxed worlds. Bone dry and unreasonably tight. The carpenter’s last rind of imagination was used up by these things. Conjuring the sea, the shipwreck and the raft he would have lashed together from the Evelyn tables, to save himself and the cork tombs. This is the memory that floods to him, every morning under the smoke-filled trees.

The empty bandstand, just before work, will be forgotten in seconds.

The daily round of work and hiding has begun with the first ritual of clocking in, punching time holes out of his named label. He knew where the uncomfortable places were. Most of the broken furniture came from there. His repairs kept him locked in association with a catalogue of invisible incidents. Sometimes, while concentrating on a splintered chair or a cracked window, he would realize he was no longer alone. He was sharing the room with a displacement that wrote its contours of nothing in human form.

Yesterday upon the stair, I saw a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today. I wish that he would go away.

Sometimes they crept through the carefully layered protective skins of drink. Insinuating themselves against his whilsting frame, as if invited, as if kindred, as if warming their distance on his translucence. Everything in the rooms and corridors was complacent and eloquently engaged in the act of being still. Not breathing in this vulgar time. One of the rituals was rewarded by a tiny yearly stipend. The daily winding of an ancient clock, nested on a high dark shelf, and accessible only by a perilous ladder. This was to be his undoing. The mournful walnut-and-brass cluck counted the moments away, reeling the accident in: face to face. But for now he is safe and the day gently spills towards evening. A couple of drinks to rectify freedom and prepare for the journey back. Which will remain unbroken until the Oakdale. This is a bad time between drinks and sanctum, the way home is not level. The ragged shadows are hungry and struggling against weak gravity.

Returning is a different matter, its form distorted by a saline of time. It is not the reverse or opposite of setting out, but an entirely other ritual. The carpenter’s way back to his wife and numbered house was drenched in mishap. The balance of humours slewed, swilling him into bait. Even worse, his crooked path was trespassed by an unkindness of sleep. A purple-black undercurrent that is beyond conscious control and knows its place of attack with uncompromising bilious guile. For this solitary man, it was lived underground: waiting in the shuddering echo of the Piccadilly Line. It should have been the sleep of fatigue that, in its innocent stage, offers the collapsing of time as a gift, letting the homecomer doze away the lagging boredom, scooping a chunk of dismal event out of its trapped sequence. But this was an angry and vindictive other, gnawing with contempt for any citizen who had spilled or wasted its benediction. A worse cruelty was the absence of dreams. So he rattles in a little smudged light of the worming train, speeding under the vast city. There is no rest. His gummy doze is full of chiselling joints, shudders that pretend to be falls, slips from the edge of sentience. The other passengers don’t notice his eyes holding on to consciousness, between heavy-lidded blackouts.

He leaves the train at Manor House, one of the deepest stations in London, and walks the final yards, past his front door, looking down, towards the next street and the Oakdale Arms. It is eight-thirty in the evening and he will drink here for another hour. Rotating his mood into a woollen jubilance, blotting out the day, the journey and tomorrow; but worst, the embarrassment of having to spend a short blurry time with his wife. His dinner has been in the oven warming since seven o’clock. The time at which he should have arrived home. By ten the food will be soldered to the plate, desert hot. This tragic sadness occurs every day and is the only act of exchange between man and wife. It is another clocking in, a silent treaty of failure. The ultimate emotional manifestation of invisibility.

The morning and the alarm clock wait. The other clock at the Inns of Court will watch for three more years, before he falls. When he is taken to hospital, his routine is snapped. The staff are on strike and he is becoming delirious as the pain and the DTs chew into him. He becomes simultaneously transparent and solid. The carefully preserved balance wheeling into overspill. The ghosts find him. His family stare through an absence. He is caged in a cribbed bed, high sides restrain him. The dropped food and broken plates are swept under his bed. Domestic and nursing staff are protesting in the streets.

He gibbers, rages and swoons. The cot is shaking apart, while his family, catatonically locked in obligation, are sitting close by, unable to see the man in the creature that dissolves before them. The vigil lasted a week, until he was no longer there and the room was filled with a smouldering gas of shadows.

Many of the places, acts and histories have gone since his time. Some have changed beyond recognition. But the layers that describe and bind us are still permeable. Those that are here have a duty to those that are almost here, and those that have been, and especially to those in between. The carpenter can finally be found, downing the invisible, gradually sobering towards yesterday, in and between: the Blue Anchor, the Seven Stars, the George IV, the Ship, the Fox & Anchor, the Wicked Wolf, the Bishop’s Finger, the Sutton Arms and the Oakdale and all those others that pretend to be gone.

[Brian Catling]

How unmeaning a sound was opium at that time! what solemn chords does it now strike upon my heart! what heartquaking vibrations of sad and happy remembrances! Reverting for a moment to these, I feel a mystic importance attached to the minutest circumstances connected with the place, and the time, and the man (if man he was), that first laid open to me the paradise of Opium Eaters. It was a Sunday afternoon, wet and cheerless; and a duller spectacle this earth of ours has not to show than a rainy Sunday in London. My road homewards lay through Oxford Street; and near ‘the stately Pantheon’ (as Mr Wordsworth has obligingly called it) I saw a druggist’s shop. The druggist (unconscious minister of celestial pleasures!), as if in sympathy with the rainy Sunday, looked dull and stupid, just as any mortal druggist might be expected to look on a rainy London Sunday; and, when I asked for the tincture of opium, he gave it to me as any other man might do; and, furthermore, out of my shilling returned to me what seemed to be a real copper halfpence, taken out of a real wooden drawer. Nevertheless, and notwithstanding all such indications of humanity, he has ever since figured in my mind as a beatific vision of an immortal druggist, sent down to earth on a special mission to myself. And it confirms me in this way of considering him that, when I next came up to London, I sought him near the stately Pantheon, and found him not; and thus to me, who knew not his name (if, indeed, he had one), he seemed rather to have vanished from Oxford Street than to have flitted into any other locality, or (which some abominable man suggested) to have absconded from the rent. The reader may choose to think of him as, possibly, no more than a sublunary druggist; it may be so, but my faith is better. I believe him to have evanesced. So unwillingly would I connect any mortal remembrances with that hour, and place, and creature that first brought me acquainted with the celestial drug.

[Thomas De Quincey]

In 1831, the obscure region of Bethnal Green known as Nova Scotia Gardens had notoriety thrust upon it, when body-snatchers John Bishop, thirty-three, and Thomas Williams, twenty-six, moved in; alas, they did not restrict themselves to snatching corpses from graves, having found an ingenious way of ensuring that the human flesh they delivered to London’s surgeons was as fresh as it could possibly be.

Nova Scotia Gardens has never appeared on any map. It never will. No one has used the name since the late 1850s. While it lived, the acreage it occupied was marked on maps as ‘Garden Grounds’ or ‘The Gardens’, if it was named at all; often, it is shown as empty space, dotted with a few cartographic icons of trees and a scattering of dwelling houses.

It lay not far to the north of St Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch High Street, and was bordered to the west and north by the curve of Hackney Road and to the south by Crabtree Row (today’s Columbia Road). It was overlooked by the Birdcage pub, which is still to be found at the spot where Columbia Road makes a sudden jerk to the left.

The level of the Gardens’ ground was slightly below that of the surrounding streets, and so some locals also referred to the place as the Hackney Road Hollow. Another early name for the territory was Milkhouse Bridge – probably/possibly in connection with a farmhouse constructed on the spot during the Restoration period. At the start of the eighteenth century, the Gardens were ‘Goodwell Garden’; by 1746 – the year of the publication of John Rocque’s famous map of London – they appear to be largely unbuilt-upon fields, on the fringes of the Huguenot settlement of Spitalfields, to the south. It is unlikely, but not impossible, that the punctilious Rocque would have failed to indicate that housing occupied the site; but Stow’s Survey of London (1603) refers to some houses recently built just to the north of St Leonard’s Church upon ‘the common soil – for it was a leystall’ (dunghill), and if this is a reference to the Gardens, it would indicate that the development was Jacobean in origin.

By the early 1800s the older horticultural and food-related names of the surrounding lanes and roads (Crabtree Row, Birdcage Walk, Orange Street, Cock Lane, Bacon Street, Sweet Apple Court) were being joined by the martial, naval and colonial references of the brick-built terraces springing up in the vicinity. The Gardens had become Nova Scotia Gardens, and near by was Virginia Row, Nelson Street, Gibraltar Walk and Wellington Street.

The Gardens comprised a number of cottages which by 1831 were noticeably quaint; they were interconnected by narrow, zigzagging pathways. In July 1830, John Bishop, a prolific body-snatcher, or Resurrection Man [see ‘Resurrection Men’, p. 152], had rented No. 3 Nova Scotia Gardens from its owner, Sarah Trueby, living there with his wife and three small children; one year later, Trueby rented No. 2 to a young man just out of Millbank Penitentiary – Thomas Williams had served four years of a seven-year sentence for stealing a copper pot.

Nos. 2 and 3 formed a semi-detached unit and were not in among the labyrinth of Nova Scotia Gardens, but close by Crabtree Row and near to the main entrance into the Gardens. John Bishop’s house, No. 3, had a side gate, opening on to a path known locally as The Private Way, and the house was entered by a back door, close to a coal-hole. No. 2 opened directly on to the largest path, connecting the Gardens to Crabtree Row. A four-inch brick wall separated the dwellings.

Each cottage consisted of two upstairs rooms, a downstairs parlour, eight foot by seven, a smaller room from which the staircase rose, and a small wash-house extension. The downstairs window overlooked the back garden. The roof of Nos. 2 and 3 sloped sharply down from the front of the building to the back, and this may indicate that the cottages were built – like so much housing in Bethnal Green, Shoreditch and Spitalfields – as homes for weavers: the lack of an overhanging front gable would allow light to pour into the upper rooms, which may once have contained hand-looms.

Each cottage had a thirty-foot-long, ten-foot-wide garden, divided from its neighbour by three-foot-high wooden palings, in which was a small gate. At the end of each garden was a privy. In the garden of No. 3 was a well to be shared by Nos. 1, 2 and 3, though in fact the residents of many of the cottages could have reached it easily; it was halfway down the garden and comprised a wooden barrel, one and a half foot in diameter, sunk into the soil. The generous size of these back gardens, together with the fact that mulberry trees appear to have been growing there, may reflect an earlier use as tenter grounds, to stretch and dry silk; silkworms lived on mulberry leaves [see ‘Silkworms’, p. 274].

The ground on which the cottages perched was described by one 1831 commentator as ‘former waste – slag and rubbish’, and it is possible the cottages had been built on the site of a brickfield, of which there had been a great many in Bethnal Green in the eighteenth century, supplying the fabric of the ever-expanding capital city. The earth would be torn up and baked into bricks in kilns built on site. Another theory is that the Gardens had once been allotments, and that the cottages had developed from a colony of gardeners’ huts or summer-houses.

The Gardens and their surrounds had, during the 1664/5 plague visitation, seen some of the highest mortality figures in the capital. In 1831, its old reputation for poverty and despair was returning. Letters from Londoners concerned about conditions in this part of the East End – unpaved, undrained, unlit – were starting to appear in the newspapers. The Morning Advertiser printed a complaint about the filth outside the violin-string workshop in Princes Street, just south of Nova Scotia Gardens – a mess (mainly comprising offal) that was five foot wide and one foot deep; while ‘An Observer’ wrote to the same paper to report the level of filth in nearby Castle Street.

But the most calamitous era for Nova Scotia Gardens was still to come. When John Bishop and Thomas Williams were arrested, on 7 November 1831, after delivering a suspiciously fresh corpse to King’s College Anatomy School in the Strand, Police Superintendent Joseph Sadler Thomas searched Nos. 2 and 3 for evidence that would back his hypothesis that Bishop and Williams had advanced from grave-robbery to ‘Burking’ (after Edinburgh’s infamous murderers-for-dissection Burke & Hare), in their bid to supply the surgeons. Superintendent Thomas would later say that he had found Nova Scotia Gardens ‘remarkable’; that there was not a street lamp within a quarter of a mile of the place; and that he considered No. 3 itself to be ‘in a ruinous condition’.

The examining magistrate asked Superintendent Thomas whether it was true, as he had heard, that Bishop’s house lay ‘in a very lonely situation’, the sort of place where evil deeds could be committed unseen. Thomas had had to reply that in fact the Gardens was ‘a colony of cottages’, and that one had only to step over the small palings in order to have access to at least thirty other dwellings.

In Bishop’s cottage, Thomas had come across two chisel-like iron implements, each with one end bent into a hook; a bradawl with dried blood on it; a thick metal file; and a rope tied into a noose. They looked incriminating, but the police officer knew that they were simply the paraphernalia required by a Resurrection Man. He knew that a court would recognize them as such, too.

No. 3 had contained surprisingly little else: a rickety old cupboard, the marital bed, a large pile of dirty clothes in one corner of the parlour, a child-sized chair, a few household bits and bobs.

Thomas decided to search the well in Bishop’s garden; it was covered over by planks of wood, on to which someone had scattered a pile of grass cuttings. From the bottom of the well he fished out an object that proved to be a shawl wrapped around a large stone.

Thomas had found nothing of note in Williams’s cottage, No. 2, but from the bottom of its privy in the garden he retrieved a bundle: unwrapped, it comprised a woman’s black cloak which fastened to one side with black ribbon, a plaid dress that had been patched in places with printed cotton, a chemise, an old, ragged flannel petticoat, a pair of stays that had been patched with striped ‘jean’ (a heavy, twilled cotton) and a pair of black worsted stockings, all of which appeared to have been violently torn or cut from their wearer. There was also a muslin handkerchief, a red pin-cushion, a blue ‘pocket’ (a poor woman’s equivalent of a purse, or small, everyday bag) and a pair of women’s black, high-heeled, twilled-silk shoes. The dress and chemise had been ripped up the front, as had the petticoat, which also had two large patches of blood on it. The stays had been cut off in a zigzag manner.

On Thursday 24 November, nearly three weeks after the arrests, two admission booths were set up outside Bishop’s House of Murder, as No. 3 Nova Scotia Gardens was now known. The police had asked Sarah Trueby, owner of Nos. 1, 2 and 3, if some arrangement could be made whereby visitors could enter the House of Murder, five or six at a time, paying a minimum entrance fee of five shillings – a move officers hoped would prevent the house being rushed by the hundreds who were thronging the narrow pathways of the Gardens and straining to get as close to the seat of the horror as possible. Sarah Trueby’s grown-up son told the police that he was concerned about his family’s property sustaining damage and asked the officers if they could weed out the rougher element in the crowd. Somehow, some kind of pretence of decorum was achieved, and it was reported that ‘only the genteel were admitted to the tour’. Nevertheless, the two small trees that stood in the Bishops’ garden were reduced to stumps as sightseers made off with bark and branches as mementoes – ditto the gooseberry bushes, the palings, the few items of worn-out furniture found in the upstairs rooms, while the floorboards were hacked about for souvenir splinters. An elegantly dressed woman was seen to stoop down and scoop up water from the well in which the macabre find had been made, in order to taste it. Local lads were reported to have already stolen many of the Bishops’ household items, and around Hackney Road and Crabtree Row a shilling could buy the scrubbing brush or bottle of blacking or coffee pot from the House of Murder.

*

Bishop and Williams died for their crimes, and their bodies then suffered the fate of executed murderers: they were anatomized by London’s surgeons. The ‘Case of the London Burkers’, as it became known, brought Nova Scotia Gardens another, unflattering, name: for the remainder of its life it would be known as Burkers’ Hole, and a myth arose that the cottages communicated with each other via a warren of cellars and subterranean passages – a vivid image of how London’s criminal fraternity were felt to be able to move around unseen along secret pathways of their own making.

In the late 1830s and 1840s Nova Scotia Gardens was one of the slums traversed by such sanitary reformers as George Godwin (founding editor of the Builder magazine); Dr Southwood Smith (who took the Earl of Shaftesbury to see how the cottages regularly flooded because they were so low-lying); Henry Austin (Charles Dickens’s brother-in-law); and Dr Hector Gavin (author of the compendium of East End fever haunts Sanitary Ramblings, 1848). By the late 1840s a refuse collector was using Nova Scotia Gardens as his official tip, accumulating a vast mound of waste – all manner of metropolitan rubbish, including human and animal dung – from which the still destitute residents of that part of Bethnal Green came to salvage some sort of living. Godwin decided that ‘an artistic traveller, looking at the huge mountain of refuse which had been collected, might have fancied that Arthur’s Seat at Edinburgh, or some other monster picturesque crag, had suddenly come into view, and the dense smell which hung over the “gardens” would have aided in bringing “auld reekie” strongly to the memory. At the time of our visit, the summit of the mount was thronged with various figures, which were seen in strong relief against the sky; and boys and girls were amusing themselves by running down and toiling up the least precipitous side of it. Near the base, a number of women were arranged in a row, sifting and sorting the various materials placed before them. [See ‘Fairies’, p. 178.] The tenements were in a miserable condition. Typhus fever, we learned from a medical officer, was a frequent visitor all round the spot.’

‘Refuse’ was Godwin’s euphemism for human faeces; Dr Hector Gavin described the same scene as ‘a table mountain of manure’ and ‘excrementitious matter’, which towered over ‘a lake of more liquid dung’. Gavin complained that the Gardens had become ‘a resort for all the reprobate characters in the vicinity on Sundays, who there gamble, fight, and indulge in all kinds of indecencies and immoralities. The passersby on Sundays are always sure to be subjected to outrage in their feelings, and often in their persons.’

Half a century later a nostalgia column, ‘Chapters of Old Shoreditch’, in the local newspaper, the Hackney Express & Shoreditch Observer, featured an aged local resident’s eyewitness memory of ‘the fearful hovels…once so famous in the days of Burking – a row of dilapidated old houses standing back from the line of front-age and in a hollow, with a strip of waste land in front, on which was laid out for sale flowers, greengrocery and old rubbish of all kinds’.

Royalty came to gawp at the natives too, and discovered that nature always finds a way: Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck – granddaughter of George III and mother-in-law to the future George V – recalled of the Gardens: ‘There was a large piece of waste ground covered in places with foul, slimy-looking pools, amid which crowds of half-naked, barefooted, ragged children chased one another. From the centre arose a great black mound…the stench continually issuing from the enormous mass of decaying matter was unendurable.’

But the most important visitor to these foetid regions was Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), millionairess, philanthropist, baroness (from 1871) and, for two decades, close friend of Charles Dickens. Together, the baroness and the novelist would take long night-walks to some of the ‘vilest dens of London’ during the 1840s and 1850s; and from time to time the ‘Ruins’ (yet another local name for Nova Scotia Gardens) featured on their East End itinerary; to Burdett-Coutts it was ‘the resort of murderers, thieves, the disreputable and abandoned’. In 1852, she bought Nova Scotia Gardens for £8,700. She intended to raze the cottages and in their place build salubrious homes that would lead to the moral, spiritual and physical improvement of the dwellers of Burkers’ Hole. But she had not been informed that the refuse collector was legally entitled to stay on the land – no matter who owned it – and to use it as he saw fit until 1859. It was only in that year that she was able to set about her grand project. She employed architect Henry Darbishire to create Columbia Square, a magnificent five-storey block of one-, two- and three-room apartments, housing 180 families who paid between 2s 6d and 5s a week in rent; there were shared washing facilities and WCs on each floor, and a library, club room and play areas. Every summer, Burdett-Coutts chartered two steam trains to take the entire estate to a garden party at her Highgate villa, Holly Lodge. A waiting list of families keen to move into the flats quickly grew.

Columbia Square was an odd amalgam of industrial-dwellings-style tenements on to which were grafted the pinnacles and pointed arches of Gothic; plain yellow stock bricks were dressed with Port-land stone and terracotta mouldings. What followed next was even more exotic: Columbia Market, built just to the west of the Square between 1863 and 1869, was a Castle Perilous extravaganza that included 36 shops and 400 market stalls for local traders and coster-mongers. The costermongers were specifically catered for in Columbia Market; where previous philanthropic housing ventures had created no room or facilities for the costers’ donkeys, Burdett-Coutts built stables for the animals, and sheds for the barrows they pulled. She helped to found a sort of union, the Costermonger Club, which presented her with a small silver donkey in thanks; this would remain one of her most treasured possessions.

Columbia Market looked like a miniaturized cathedral and came complete with pieties painted on the walls, such as ‘Speak everyman truth unto his neighbour’, and orders forbidding swearing, drunkenness and Sunday trading. It went bust within six months.

The baroness’s housing, however, continued to be popular for nearly 100 years, but Columbia Square was finally condemned as unfit for human habitation in the 1950s; the Market died alongside it (Britain’s heritage bodies having not yet realized their lobbying skills), and Henry Darbishire’s masterpieces fell to the demolition ball in 1960.

Today, the Dorset Estate (named after the Tolpuddle Martyrs) is Nova Scotia Gardens’ latest incarnation, though, like all the others, it’s not a name that’s likely to stick. Its architect, Berthold Lubetkin, is probably most famous in this, his adopted nation (he fled the Soviet Union, arriving in Britain in 1931), for the Penguin House at London Zoo. On the site of Bishop and Williams’s depredations, the staircase that soars through the nineteen floors of Sivill House (completed in 1966) has distinct echoes of the penguins’ Modernist home.

There are sadder, nastier echoes: in 2002/3 four people were murdered at Sivill House within a nine-month span. Psychogeography? I think not. Isolated tragedies, with poverty playing at the very least a walk-on part.

Time has written some very odd features on to the face of the Gardens: the zigzags of the colony of tiny, quaint cottages; the mid nineteenth-century hillock of shit; the philanthropic towers of Angela Burdett-Coutts; and, now, the stark geometry of post-war high-density housing and Lubetkin’s monoliths.

[Sarah Wise]

In those times, nearly every shop, warehouse or commercial establishment was marked by its particular sign. In many instances, these signs were emblematical representations of the trades carried on in the houses…But there were also many cases in which the signs were not symbolical of special trades, and were merely used as distinctive characteristics of various commercial establishments. Thus representations of bears, lions, dogs, crowns, bee-hives, wheat-sheaves, &c, were hung up as signs; and the progress of luxury introduced a refinement even into this department – so that the streets of London at the period of which we are writing were filled with green dragons, golden elephants, blue bears, red lions, yellow dolphins, and such like incongruous inventions.

[George W. M. Reynolds, 1849]

FAIRIES

A disappeared trade: a London-wide community of women who made a living sifting the city’s rubbish dumps, given the Cockney ironic name of ‘Fairies’. Described by a London City Mission welfare worker in 1905 as ‘strong, coarse women…knee-deep in dust. That which passes through the sieve goes to help make bricks, while that which remains in the sieve goes to burn the bricks. The pots, pans, kettles and dead animals are picked out and placed on one side.’ The Fairies worked alongside ‘Bobblers’ – men who shovelled the rubbish into their sieves. If she rose to the top of the profession, a Fairy was said to have become a ‘Queen’; the job often passed from mother to daughter.

[Sarah Wise]

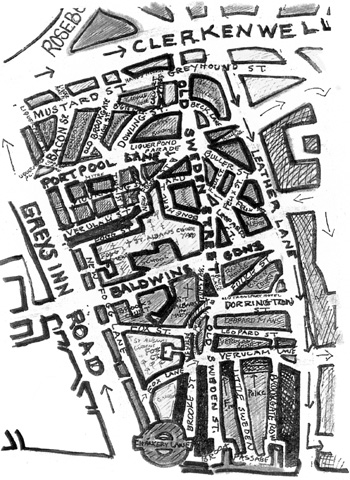

HOCKLEY IN THE HOLE, ECI

A district removed during the ‘Clerkenwell Improvements’ of the mid 1850s. The Hole (at the lowest part of today’s Ray Street) was a tiny valley into which the nearby Fleet regularly flooded; ‘hock’ meant miry. From the seventeenth century Hockley was famous for its bear gardens and small amphitheatre, in which cock- and dog-fighting spectacles took place, and bears, bulls and donkeys would be baited and tormented – sometimes by having fireworks tied to them.

[Sarah Wise]

LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS SHANTY TOWN, WC2

In 1988, as rough-sleeping in the UK increased dramatically, hundreds of homeless people put up their tents and cardboard-box ‘bashes’ in the gardens of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. This metropolitan shanty town was forcibly cleared and its inhabitants dispersed in March 1993.

[Sarah Wise]

GRESHAM CLUB, E4

The Gresham was a gentleman’s luncheon club, established in the nineteenth century, and functioning in 1969 in much the same way as a hundred years before. Meg and I, dedicated Marxists, reluctantly abandoned our miniskirts for waitresses’ black and white, and set about trying to undermine the false consciousness of the permanent staff, to little effect. The gentlemen, city types and assorted worthies, undoubtedly shaping the fate of smaller nations, sat in their dull dark suits at refectory tables. ‘Miss,’ one would cry, ‘my napkin ring is missing.’ And we sifted through the engraved silver christening rings and tortoiseshell and probably whalebone and meteorite, because gentlemen could not be expected to eat without their own napkin ring before them. The food was predictable, public-school dinners: veal, ham-and-egg pie, steak-and-kidney pudding, spotted dick. I stopped by a balding man with glasses, my order-pad at the ready. ‘My usual.’ He went on with his conversation. ‘It’s my first day; perhaps you could tell me what your usual is?’ ‘I am Lord Carrington,’ he said. ‘Find out.’

[Ruth Valentine]

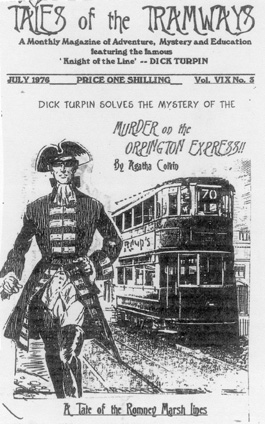

LIVESY WALK, BROOKGATE, ECI

Running between Leather Lane and Brookgate Market, Livesy Walk is best known for its eighteenth-century inn, the Three Jolly Dragoons – where, legend has it, Dick Turpin and Tom King held court during the Golden Age of the Tobeymen (mounted highway-robbers whose exploits were finally brought to an end by the introduction of the electric tram). A few tobeymen continued to waylay trams run by the London Universal Transport Co., though the famous cry of ‘Throw down your lever’ was a myth propagated in such boys’ papers as Thrilling Tramway Yarns and The Dick Turpin Library. Livesy Walk was later the residence of Edward Holmes, Desmond Reid and a number of authors, all of whom worked for the Amalgamated Press, which was situated near by. Between 1910 and 1914, the Walk was the fictitious address of the ‘office boy’s Sherlock Holmes’, Sexton Blake. Arnold Bennett lived here for a short time, after his return from France in 1912.

[Michael Moorcock]

COVENEY’S YARD, EC3

Although the Elizabethan courtyard has now disappeared, the name is still attached to the Brookgate flats (built in 1990). Until the early years of the twentieth century the Yard was best known for Coveney & Child’s Medical Supply Stores – the chief importers of opium and morphine, suppliers to London society (including many theatrical celebrities). George Grossmith refers to ‘Coveney

The final issue of Tales of the Tramways. ‘A kind of popular fiction unique to London’ – Cyril Connelly. Hugely popular in the 1920s and 1930s, Tales had by 1970 become primarily a comic book.

the Younger, the Happiness Monger’ in one of his comic songs. De Quincey mentions ‘Coveney’s Comfort’ in a footnote to his second revision of Confessions of an English Opium Eater. For a short time, in the 1870s, Coveney & Child enjoyed the prestige of a royal warrant.

[Michael Moorcock]

THE OLD MOON & STARS, FOXES ROW, E3

Named for Sir John Moustiere, the first Huguenot judge in London, the Old Moon & Stars was originally a coffee shop. It is mentioned by Goldsmith in an essay published in the Monthly Review (1758). (The New Moon & Stars is located in Dykes Street, Smithfield, and is notable for its ‘blood worms’ – the black sausages that are still sold, on request, in the teeth of Euro regulations.)

The Old Moon & Stars became a public house during the middle part of the nineteenth century and was noticed by Dickens in several articles for Once a Week. The association with Master Humphrey’s Clock is recalled in dubious memorabilia. A framed document claims that in the first draft of the tale Dickens portrays Adjutant Slate holding court in the pub.

The house sustained some damage during the Blitz but was restored in 1965. The proprietor, Tommy Mendes, had a reputation in the East End as a bare-knuckle boxer. He can still be brought downstairs to talk to customers who are making a disturbance. In recent years, thanks to a relaxation in the licensing laws, fifty kinds of absinthe have been made available – including the famous ‘Red and Yellow’ (95 p.c. proof).

[Michael Moorcock]

The last sewer I was working at

was the sewer at Blackfriars-bridge that

played the deuce with me that did

we pulled up an old sewer had

been down upwards of 100 years &

under this a burying-ground we dug

up I should think one day about

seven skulls & as to leg-bones

oh a tremendous lot of leg-bones

to be sure I don’t think men

has got such leg-bones now the

stench was dreadful we knocked off day-

work & was put on to night-

work to hide it after that bout

I was ill at home for a week

we nails our lanterns up

to the crown of the

sewer when the slide is

lifted up the rush is

very great & takes all

before it roars away like

a wild beast we’re obligated

to put our heads fast

up against the crown &

bear on our shovels so

not to be carried away

& taken bang into the

Thames there’s nothing for us

to lay hold on if

taken off our legs there’s

a heavy fall about three

feet just before you comes to the mouth if we

was to get there the

water is so rapid nothing

could save us

Great black

rats as

would frighten

a lady into

asterisks to

see

of a sudden

[John Seed/Henry Mayhew]

‘A DESERT IN THE HEART OF LONDON’

The extensive and complicated network of lanes, courts and alleys covering the area bounded east and west by Bell Yard and Clement’s Inn, north by Carey Street, and south by the Strand and Fleet Street, lately containing a population more numerous than that of many Parliamentary boroughs, is being fast deserted. A few of the winding thoroughfares are not yet disturbed, but several of old and worse than equivocal notoriety – and in which, a few weeks ago, passage was rendered somewhat difficult by the human swarms whose modes of existence are among the unsolved social mysteries – are now almost uninhabited, only a house or two remaining, in exceptional cases, where a brief extension of term has been granted. Massive padlocks guard every door. The glass on the first and second floors has been smashed in by unforbidden missiles discharged as parting salutes by the more juvenile emigrants, and the grimy, stooping, unwholesome buildings wear an aspect of weird gloom, contrasting strangely with their recent animation, when every doorway and window arrested passing attention with grotesque and sordid samples of human nature. The ground taken by the authorities intrusted with the arrangements for the new ‘Palace of Justice’, or, in plain English, the new law courts and offices, includes nearly thirty lanes and passages, the names of some of which will be familiar to all who have made acquaintance with the topography of London. Among them is Clement’s Lane, the south part of which, nearly up to King’s College Hospital, comes down. Here still stand some old houses, the very peculiar, perhaps unique, character of whose construction is worthy of a visit. One of them is remarkable as the scene of one of those Royal intrigues and misdeeds which figure in the Méemoires pour Servir of Charles II and his Court. Then there is Bell Yard, the seat of newsvendors, law booksellers and printers…Next come Middle and Upper Serles Place, with Lower Serles Place, formerly Shire Lane; Ship Yard, mentioned more than once in the chronicles of seventeenth-century roysterings; Crown Court, a dilapidated passage…with its noisy and dangerous neighbour, Newcastle Court.

The main frontages to come down are, northwardly, nearly the whole of the south side of Carey Street, and, southwardly, the eastern and western extremities respectively, the north side of the Strand and Fleet Street, crossing Temple Bar. The pulling down of the south frontage will probably be deferred until some way has been made in the removal of the passages to the rear. By the displacement of so many hundreds of poor families, the unhealthy courts about Drury Lane, Bedfordbury, the Seven Dials and other localities, already reeking and noisome with excess of numbers, have become more overcrowded than ever. The rents of the most miserable rooms have materially risen, and another entanglement is added to the difficult problem, ‘How and where are the poor to find suitable dwellings?’

[The Times, 12 November 1866]

‘LOST GRAVE OF WILLIAM BLAKE FOUND IN LONDON’

The keeper, the Irishman, was unusual. He was there when youneeded him, but otherwise invisible. When Bunhill Fields was the subject, this man was always mentioned by initiates. Some said he was an artist, a painter. They didn’t know his name, had never set eyes on his work. There was a distance, certainly, between the person who stood, so obligingly, before you, and whoever came, by accident or whim, to the old Nonconformist burial ground on the edge of the City. The unlucky Cromwells, he had those on tap. He would unlock a low gate and lead youto the relevant memorial, the chipped or erased tomb. He had the stories, without the compulsion to inflict them on you. And he did his job, quietly and efficiently: the gardening, sweeping, toilet cleaning. The brewing of regular mugs of tea.

A slight figure in baseball cap and overalls, you may have noticed him ghosting through television films, local-interest documentaries. The man solved one of the mysteries of the place. Who, I wanted to know, left flowers on the grave of William and Catherine Blake? There was no such tribute for Daniel Defoe or John Bunyan. Pass through as early as you like, they were there, in a jam jar; fresh, modest. A splash of colour against the grey. ‘That’s me,’ he confessed. But I think the coins which have recently made an appearance are not him. Brown. Leaving a stain when they are lifted – so that new tributes can be placed, next morning, in exactly the same position. Three groups of coins on the rim of the thick slab: five at each end and seven on the highest part, the curve. I’d have made something of that once.

The keeper rubbed his nose with a knuckle and confirmed what I’d read in The Times (16 April 2005), Blake wasn’t here. The much-loved memorial was just that, a prompt marking nothing, marking absence. Two ‘amateur sleuths’ – Carol Garrido, a landscape gardener, and her husband, Luis, a law graduate – had ‘used records from Bunhill Fields Burying Ground Order Book to find the grave’s coordinates’.

The present memorial had been set up in 1960, an episode of civil pride, to smooth over minor bomb damage, after the Blitz. Fading newspaper photographs of moustache-and-black-hat dignitaries, taped to the window of the keeper’s hut, made it absolutely clear: the dedication ceremony happened elsewhere.

We looked at mute grass and away to the west, beyond the line of trees, to the obelisk of St Luke’s, Old Street. Not a trace. Not one degree of the original heat. A communal grave: even in death, a shared tenement for the Lambeth poet. I read out the list of names, co-tenants of this Clerkenwell pit: Margaret Jones (37), Rees Thomas (53), Edward Sherwood (53), William Blake (69), Mary Hilton (62), James Greenfield (38), Magdalen Collin (81) of Bethnal Green Road, Rose Davis (58).

The Necropolis Company took a million-pound contract to clear the slumbering dead, in strong green bags, from beneath St Luke’s. Winter rains turned earth to muddy soup. Kosovans were employed – willing, active workers – to feel, blind, for bones, scraps of cloth, coffin wood. And then the logged remains, details entered in an antique ledger, were taken out to the suburbs and bulldozed into a mass grave. Which was soon returfed and rolled.

‘They’re everywhere,’ said the man who made the film. ‘London is a great mound of bones. We are walking on the faces of the dead.’ Before Brookwood, the funeral trains out of Waterloo, and the suburbanization of death, our immediate forefathers were much closer to the surface. Hands reached out of the ground, literally: Hoxton urchins were challenged for wearing small fists of signet rings. Respectable matrons, walking nervously through churchyards, skidded on human skin, mortality’s leather.

Blake was put to earth with a charabanc of East Enders, recent immigrants from the Celtic fringe. No alcove in St Paul’s, no effigy in winding sheet. No heritage plate (like a royal-blue satellite dish), not then. And better so. Beyond the reach of vulgar curiosity. A stone postcard in the shade of a fig tree. And the company of other distinguished absentees. All under the patronage, the casual and affectionate custodianship, of this Irishman, my guide. His daily jam jar of garage flowers.

[I. S.]

THE VEGETATIVE BUNYAN

After completing our three-and-a-half-day hike, Epping Forest to Glinton, in pursuit of the ‘peasant poet’ John Clare, I returned to London and Bunhill Fields. My companion, Renchi Bicknell, had broken away from a solitary expedition he was undertaking, as a way of restoring his sense of place, after a period spent in India: he was walking, in a kind of disembodied reverie, from Boston (on the Wash) to Abbotsbury in Dorset. A raw-food diet left him floating several inches above the ancient flags. To keep himself grounded, he looked for difficulty and filled his pockets with the relevant stones.

That triangulation, Blake-Defoe-Bunyan, covers it. Everything in old London, in England, moves out from here. A shaded enclosure, a green passageway: beyond the City walls the melancholy susurration of the nonconforming dead.

The relief panel on Bunyan’s generous monument is what we are both after, what we have been doing all these years: the Pilgrim, his back horseshoed by a grotesque burden, leans on a staff. It’s what Jeff Kwinter, the rag-trade magus, said to me, years ago: ‘You’re always schlepping something across town. That’s your karma.’ Books, cameras, unwieldy kit. Blake’s version of the Pilgrim, stooping under a maggoty chrysalis rucksack, reading as he walks, was the frontispiece of my first London book, Lud Heat.

The sleeping figure of Bunyan, face to the rising sun, has been groomed. He is no longer the vegetative god, the albino sacrifice: lichen for nose hair, black fur to emphasize the cheekbones. White plaster crumbles as the traveller, the tinker, breaks out of his mummy case. The cracked skull leaks light. It dissipates, quietly, noticed only by the scholarly Irish custodian, keeper of the stones. It drains across the darkening burial ground; over lesser Cromwells and other forgotten exiles; over Milton’s death chamber, the small markets and lost theatres of metatemporal London.

Bunyan is the emblem of transformation. Another floater: kept in place by the anvil-weight of his sepulchre. His eyes are pads of emerald moss. Wavelets of chalk hair flow back into the empty tank. Accidents of dust and corruption sculpt a white mask, a flash into negative. Anorak groups are brought here to witness a continuing absence. They confirm it with cameras.

Gerda Norvig, in an account of Blake’s illustrations to The Pilgrim’s Progress, sees this image of Christian with his burden as a form of entrapment: the man peering short-sightedly at the book is himself captured within the pages of another book, at which we, tentative readers, also peer. This gaze is not easily broken. Bunyan’s carapace disintegrates, a memento to the passage of time – but the panel with the Pilgrim is fresh and bright. The author’s death dream realized: framed.

‘A storm is brewing,’ Norvig tells us. ‘The man is bent double with wakeful pain and anguish, he wears ragged trousers and a torn shirt, and his limbs show extreme muscular exertion as if he were straining upwards against the equal and opposite downward force of his burden.’ No escape. We have come to a place that describes, flawlessly, the place to which we have come. So: disappear into the image, the stone mirror. Or stand here for ever, confirmed in your ignorance.

[I. S.]