II

Excursions

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away . . .

—Emily Dickinson

He is seated comfortably at a desk on the West Side of Manhattan.We need not know whose Georgian desk, whose handsome wall of books behind. A woman with a zip cut brushes down his gray hair, attempts to powder his forehead, which gleams under the lights. He is quite the gent in a tweed jacket and green turtleneck that brings out the green in his eyes, a good-looking man, mid-sixties, perfection of uncle.

“Use him in a pharmaceutical ad.” This crack, Director to Print Journalist, serious men making their documentary, segment of a series on wars of the century soon coming to an end. Father Murphy toys with a paperweight while the cameraman screens out the flickering light from Riverside Drive. He’s curious about the pictures on the faded walls—paintings of fruits and flowers, Italian street scenes, photos of grandchildren, must be, for the entry and this room, the study—so called by the Director—are old fashioned, somewhat lifeless. All personal items removed from the desk, just the paperweight and a student lamp with a green glass shade—pleasing, authentic. He has been told this is a pilot, low-budget, the apartment on loan.

The opening line of the Journalist: “You were hooded by the Nacionales?”

“Blindfolded.”

“Subjected, as many prisoners were, to sensory deprivation?”

“No, I heard the guns and at times the grenades. They shut me in the stable behind the chapel.There was the smell of dead animals.They senselessly killed the mules.”

“You were taken prisoner in March of ’79. A political prisoner.”

“No, they just left me. I was not important.”

“Can you give us your perspective on how the war played out in El Salvador, Father, as a man of God?”

“I would not use that expression. As a servant, I was afraid they would come back and kill me, but I was not useful to them.You want to speak with Father Jerez if he is still alive. He was responsible for any political”—the paperweight cradled—“political agenda, no more than a village getting in touch with grass-roots democracy.We were labeled as Marxists, anarchists. Jesuits empowering the poor, throwing our moral weight against the imperial history of the country.”

The Print Journalist with the recognizable name looks to the Director. The lights shut down.The Priest has been prepped.What they want is the personal story. Father Murphy is told to relax, tap into his feelings. How did he feel when chosen for Salvador? What were his sympathies working with the people? His emotions looking back on that time? The makeup girl has her way with the powder. He is brushed again, anxiously cups the paperweight until the lights go on.

“I felt blessed to be sent to the liberation. It was often a question of who’s saving who. The peasants or the priests. Under the blindfold, I thought of my father in the War to End All Wars, wounded, battle of the Marne, 1918. I was no hero, and they might as well kill me. Be a patriot. Kill a priest.That was one of their mottos.The stable stank of mule dung.You see, I should have called up Bethlehem, the Holy Child settled on straw, not the comforts of our little house in Rhode Island. Jesuits had been central to the colonial enterprise, now we were giving the people back their culture, the land they once owned. Aguileres saved me, the best assignment I ever had. I’m telling it like a soldier come home from the excitement of military engagement. Call it the time of my life, the church militant. The uniforms of the Nacionales were made in the U.S. So were their bullets.”

The Director is pleased.The Journalist flips through the pages on his clipboard.

The Priest laughs when he recalls being tagged a Marxist and goes into the details of torture, not his, the peasants’. “They only kicked me in the kidneys, bloodied my nose.”

“Let’s take that again about the Marxist.”

“Marxist, Leninist? Who were they kidding? We were talking together—priests, nuns, campesinos. Such talk is not cheap. Our work to free the poor from their silence, to give them letters and numbers to fight for land distribution. Let me tell you about Loyola, the Saint who started out as a soldier, found the pen mightier than the sword.”

“And the massacre?”

“There were two.” He begins with 1932, the Matanza, low estimate thirty thousand killed.

“The massacre, El Mazote?”

“I wasn’t there.” Goes on to 1980, those good Sisters murdered, came to Salvador from Detroit, martyrs. There was a cover-up, then their graves found. Our Ambassador to the UN put them down as political activists.They were victims of policy, the last gasp of the Cold War.”

But they are after his feelings, rage and sorrow, words that sound stale to Father Murphy. When the Director adjusts the little microphone clipped to his lapel and asks him to say it again, like a song, he thinks, take it from the top, rage and sorrow at the rape and murder of those good Sisters. For a split second the paperweight feels like a weapon in his hand. He knows he will be edited, his voice spliced in with the voices of others. From the top: “Martyrs, feeding and nursing the poor. Our woman at the UN called it a regrettable incident in the course of normal police activity.”

“Thank you, Father.”

It’s in the contract, his words will be reviewed, a release from the diocese.

“It is the diocese?”

And because he is a priest, they look respectful, the makeup girl and the Journalist with his clipboard, the Director and cameraman helping him over the cables. A car waits for Father Murphy at the door.

The next week he is walking round the courtyards of the Cloisters. The mixed bag of twelfth-century monasteries looks nothing like the Spanish-colonial cloisters of El Salvador. New York City schoolchildren, transported to the museum for a cultural outing, are fascinated by the cameras and arc lights brightening the day, the slow progress of filming. The Director has asked the Priest to wear a black soutane. He has refused. It was never the costume worn in Aguileres, or in San Salvador at the Jesuit High School. The black suit, the white turn-around collar will have to do.The camera tracks him on a path of lavender in bloom, head bowed in contemplation. Schoolchildren hushed, bees busy at the flowering thyme. He has been directed to turn at a bench so old the public may not sit on it.The Director has been granted a dispensation. Father Murphy sits, blinks the light out of his eyes.

“When you were hooded by the Nacionales . . .”

“Blindfolded.”

The kids are in the Buick, the car Isabel Murphy won for a dollar. She took a chance. To her husband, chances were a questionable way to the pot. “Gambling for Holy Name!”

Bel held the winning ticket in her hand. “First Methodist raffled a set of bone china.”

“Everyone’s doing it . . . ,” a maxim he need not finish. “The Buick dealer, a piece of work. How the hell does he come up with a four-door sedan idling on his lot?” 1943. Chrysler turning out tanks and bombers, Tim Murphy scolding his wife, but what the hell, swiping her cheek with a kiss. Talk was, the Buick dealer lived apart from his wife, kept a floozy up in Providence. “You better believe he wants more than a blessing from the Monsignor. Angling for an annulment from Holy Mother church.”

The pity of it, Bel couldn’t claim her prize. “It’s yours for the asking.”

“I’ll stick with the Ford.” A company car.

Tim, hot under the collar, inched the big shiny Buick off its blocks, where it had been displayed in front of the rectory. That Spring it sat in the lane, square in front of the Murphys’ house. After supper Bel took her driving lesson, the only time the children remembered their father blowing his top.

“You’ll kill us all.”

On Good Friday she lamed the Pinchots’ cat, which brought the lessons to a halt for a week, but Bel was determined, her body thrust forward like a figurehead on the prow of a ship until one day she sailed off, tooting at Meg Dunn on her tricycle, not stripping the gears. Hell of a year to win a car, gas rationed, so where, Tim asks, might she go beyond the school yard and her errands downtown, the few miles she walked each day before she took full possession of her prize? “The salt air will pit it.” But when Tim called Phil Dunn to build a garage, never mind lumber was scarce, the fellow was off to basic training at Fort Dix.

“And where would we have put a garage?” Bel asked. The cottage hedged in on one side, on the other a chain link fence, Property of the State, the lane ending in a steep drop to the stony breakwater enclosing the bay from the sea. So the garage was a failed phantom of protection, and best Tim could do was insure the occupants of the Buick and the green elephant itself for all it was worth. It was worth a good deal to watch his wife practice a perilous U-turn, till Bel, fully licensed, drove off on her own, clutching the steering wheel for dear life.

On her own was how he saw it, reminding Tim Murphy of Bel’s departure when she headed out west, of her letter from Chicago, which he read at night, lying on his bed in his parents’ house, plain people who had sharp words for Miss High and Mighty but came, along with the fans and Photoplay, to love Isabel Maher in the movies. The star, imagine that, who almost married their son, coming to terms with Tim’s devaluation. On sleepless nights, he unfolded the letter and read it by the overhead light, the bright sterility of his room fitted out with pulleys and weights to develop his good arm, make it do the work of two.

I am not leaving you. I am off [blot on the page] selfish dream, never certain, [blot] testing my worth. . . .

There followed the encouraging words of a love letter, which he believed until it was folded away, placed in a cigar box with his honorable discharge. He could not imagine Bel’s worth until, not to be caught sulking in the back row of the Bijou, he drove to New Haven to see her at Loew’s and bought a ticket to watch her eyes flood with false tears as a cruel old father in wedding regalia, tails and striped pants, begged his Bel to marry the wrong man. The screen lost the amber flecks in her eyes, the wry twist of her smile. Her wayward black curls were pasted to her head in a glossy helmet. No feeling stirred beyond the numb desire to watch her, as though the shrapnel embedded in his left arm traveled to his heart, testing himself with her prancing in the frivolous one-reelers, with her melodramatic gestures in cranked-out serials. Watching the chill silence of Isabel Maher in the romance that made her a star, he chose to remember the warmth of her voice leading schoolchildren in carols, breathless as Juliet of the Ansonia Terpsichordians, the firm delivery of her responses at Mass. For three years he told himself he did not want this woman on the screen, and when she returned her few words overwhelmed him with pleasure, like a first gulp of Otto Sauer’s beer, that’s how Tim Murphy described his elation. She laughed at that one, Prohibition still in place, and all she’d said, dialing Murph’s familiar number in the Brass City: You there,Tim? I’m home!

So the Buick sitting in the lane, despite the sure thing of two kids and no mortgage on the shingle cottage, presented a ghost of a problem to Tim Murphy. Where might his wife be off to? It was a brisk day at the end of April, the wind whipping the forsythia by the door. Joe and Rita already in the car when Gemma came panting down the lane, the Riccardi girl, all knees and elbows, wrists dangling from a coat too small.

“An excursion,” Bel said, “back in time for supper.”

Rita complaining. After school it was Homemakers’ Club, she’d cook meatless macaroni with the simple girls she called her friends. Joe missing baseball practice.

“Not a lark.” Bel pulled a stern face. “An educational journey.”

Tim watched them drive off, Joe up front with his mother. When he turned back to the house he found the map on the kitchen table, her route marked in ink, and worried she would not find the way. Bel had left him behind. He soaked the oatmeal pot, cleared the table, homemaker’s tasks, and thought how very sad, his daughter preferring instruction in meatless macaroni to her mother’s adventure.

Low on gas, Bel stopped at the Esso pumps before heading out of town, gave over her ration stamps and, seeing the strapping young man was taken with her smile, begged for a gallon or two on the sly, wondering, until he tried to make change, that he was not off to the war.

Isabel Murphy reads. That is why her children and Gemma Riccardi are truants: each morning, when Joe and Rita go off to school, she settles in a chair by the front window with a book. After the early clatter of the milkman and the alarming radio news, after she sees Tim out the door with his assurance and persuasions, after the beds are made and the breakfast dishes stacked in the drainer, Bel reads in the quiet of late morning. She is a woman without friends, strange to say. Oh, the neighbors are kind, and there’s Tim’s partner at Prudential, the partner’s gabby, good-natured wife, but Bel Murphy is content with her children, her husband and now and again that needy Gemma, who helps her in the garden, though the girl has no touch with living things at all.

Bel has been reading all sorts of novels from the Public Library, reading with pleasure as she did in Chatterbox days, as she did in the Hollywood bungalow when Lotte Grauber went off to endless parties. In Summer there is the garden. The rest of the year there are stories. What can be the harm of these stolen hours? Should she be at the hospital with the women rolling bandages for the wounded, or torturing herself with a tourniquet, learning first aid? These questions occur to Bel as she turns to the page marked with a shoelace where she left off when life began again—washing, ironing, meatloaf for supper. Bel settles in her reading chair, the Hoover plugged in, at the ready.

That Winter, confidence growing at the wheel of the Buick, Bel renewed one book at the library. Moby-Dick, last read with her eighth grade class in the Maplewood School, an abridged version watering the story down to Good and Evil, no wild flights in the language, a simple sea chase approved by the State Board of Education. Miss Maher had a flop on her hands—girls yawning, boys blubbering in the back of the class—and returned with a sigh of relief to the adverbial clause and the Paragraph that must contain the Topic Sentence. Picking Melville’s novel off the library shelf, she felt the heft of it and remembered teaching the lightweight fake. Each school day she sat by the front window and opened her book, marked by the brown shoelace that had lost its mate. There was the next page with its many allusions, arguments and arabesques, the writer teaching her how to read it, though at times a passage was so odd she lay the book aside, looked out at an even tempered bay shimmering in cold sunlight, Bel Murphy cast away in the comforts of the living room, clinging for dear life to the worn arm of her chair. This is where she has landed, safe as the rinky-dink plane set on the studio floor, no monkey to challenge her performance. And it seemed once again that her round trip across the country was more about leaving than arriving, setting off like the sailor Ishmael, who survived to tell the story, while she must be silent or tell only the fraudulent version. What might she call her Hollywood days—a dumb show, false start?

When the kids came down with heavy colds, seriatim, Moby-Dick sat like a brick in its brown library cover by her chair. She missed figuring the urgent sentences and her own melancholy thoughts in the winter light. In truth: there were days when Bel stumbled on the writer’s puns and fancies, the big book open on her lap while she gave herself to the gentle whitecaps decorating the bay and to sighting the boats that patrolled the shore. PT boats, Tim could name them. He’d brought Joe a chart that identified battleships and carriers, drawn circles round the ships that plied Rhode Island waters. On the chart they looked like gray toys, less dangerous than the billowing sails and creaking masts of the Pequod in Melville’s story, which would end badly, all seamen and mad Ahab dead; only the writer left to set the record straight, which was partly about commerce, wasn’t it? Whale oil. Getting and spending. She knew Melville had spent himself on this work. Bel wanted to mark this thought on a page, but it wasn’t her property, a wild book that nobody read, last borrowed seven years ago, D. Littlejohn, signature of the reader next to the date of return in the back of the book. Littlejohn, like a hearty fellow in Robin Hood’s forest, had returned Moby-Dick in two days, perhaps finding the whaling yarn overburdened with facts. Bel drifted in the pages, waiting for the kill. The phrase she committed to memory, like a line in a script, was the warning of the ship’s master before Ishmael signed on for the dangerous voyage: . . . before you bind yourself to it, past backing out.

She wondered if she was bound to finish this book. She’d never bound herself to the movies, counted herself a failure in the whirling spin of projection. A hard Winter of earaches and sore throats, measles. Moby-Dick was overdue when, one day, Bel lost her voice. The kids taunted her gently, their mother’s silence awarding them liberties, no homework, Mallomars and Cokes. That night she wandered down to her reading chair while her family slept above. The distant wail of a siren, the sky streaked with beacons of light searching out enemy planes. Making it up, she thought, Hollywood. She pulled down the blackout shades, turned on the lamp but did not read, hearing her mother’s voice pleading with her, how Maeve’s spirit had possessed her so she could not cross over to sound, would never be heard by millions worshiping her in the dark. Now she had no voice at all. She gave her passing infirmity a few tears with a little choking sound, the book open on her lap to yet another flight of fancy, the whiteness of the whale. She heard the creek of the stair tread, “Tim?”—whispering to herself as though rehearsing.

But when she turned to the shadow in the hall it was her son, tall as his father.

“Mom?” Not calling her Bel, the name she assigned herself, backing out of plain Mom. She rose from her reading chair speechless, gave him a broad smile, hand at her throat. With a theatrical gesture she swept all worry away in the middle of the night, turned off the lamp, snapped up the blackout shades. Searchlights were skimming Orion’s belt from the sky, tracking phantoms in the sea while the town slept. Her son took the book from her, laid it aside, steered her toward the stairs in the dark. She thought: Children do not want to see us troubled, wandering at night. She thought to say: It’s the war. Look what war did to your father. But of course she said nothing. Then planes swooped like gulls, followed by a muffled, watery blast. She felt her son’s arm around her shoulder, his pitching arm, strong for a boy of thirteen. Together they skip over the squeaking stair, Fred and Ginger gliding to a hesitation at the landing. Bel thinks, I will never love anyone as much as this son, partner in a midnight dance. And then: But this is not the movies.

During the night a German U-boat is chased out of the waters of the bay in view of the Murphys’ living room window. The news is on the radio as Bel sets out jam and margarine for breakfast. “Christ,” Tim says, “that’s the front yard.”

Bel’s got back a raspy voice. “And we slept through it.” She looks to her son, who says nothing.

Years later Joseph Murphy, S.J., will wonder why his mother lied. In a dark hut in Salvador, hidden under a blanket infested with rat droppings, he will think about the safe enclosure of the living room, that distant war. Across the dirt floor the campesino that brought him to this refuge is dying. He hears the butt of a rifle against a scrap of corrugated metal, poor excuse for a door, then a soldier is in the shanty, ready to kill the American priest. The soldier is a kid in a paramilitary outfit many sizes too large, the sleeves of his jacket turned up, cap slipped down on his ears. The priest thinks to shed his cover, take the M-16 away from the boy in a paternal gesture. The boy sees only a lump of filthy blanket, or maybe he is just scared. For a full minute he crouches in the dark as though playing hide-and-seek, before the distant sputter of machine-gun fire, then silence, then an urgent voice calls him away. Now the campesino is beyond the last rites. He is not of this village. The priest can’t distinguish his face from the many weathered faces of the workers who travel from plantation to plantation during the harvest. When he lifts the man’s head he notes the parched mouth of dehydration. Father Murphy remembers N. on the printed page of the rites for the dead, N. where the name of the Lord’s servant was to be inserted. The man unknown to him; this is the home of a woman he’s with for the season. The campesino had led him safely into the darkness. If the priest had guts he would have asked the dying man to make his peace with God before he hid under the blanket. Through a hole in the thatched roof, Joe Murphy looks on a bright constellation of stars and remembers his mother’s lie. Bel had not slept through the night but wandered downstairs to confront some personal demon—not Germans, not the page of the big book that he closed, took from her. He is shamed by this memory of a blip in the tranquil beat of family life. White lies, secrets at the breakfast table do not belong in this country of mass graves, of coffee-bean / sugar-cane culture feeding pickers a starving wage. The campesino has a string around his neck dangling a scapular of ragged cloth with the picture of a dove, symbol of his confradías. Lately the bishops encourage these confraternities of men mixing native beliefs with the laws of Rome. Espíritu Santo, Joe whispers to N., administering the last rites, anointing him with the oil of his sweaty brow. He takes off the dead man’s clothes, covers the body with the blanket, discards the peasant outfit Bishop Grande has dealt his priests urging them to be one with the workers as too obvious, too gringo. He will wear the bloodstained shirt, the trousers of the dead man still damp with urine, and go safely on his way.

Or not safely.

In the first light of day a woman of the village comes in with her silent children. She is wearing a long, flowered skirt, the costume of an Indian worn in defiance of Ladinos and landlords. Her silence is terrible. They might all be deaf and dumb, the inhabitants of this tin-and-cardboard hut. The children, there are four, never speak, though Father José knows the oldest, a girl he has taught to count up to twenty centavos, to add and subtract with beans. The woman uncovers the dead man and begins to dress him in the priest’s proper peasant outfit. When the man is laid out for burial, the woman goes to a crock set beside a broken water jar and ladles out cane whiskey. She brings the tin cup to Joe Murphy, raises it to his lips. For a moment he will not take it, then gulps the raw stuff, which brings tears to his eyes. Only then does she ask the American for his blessing. Together they lift the light body, carry it to a patch of dirt that served as a small communal garden, now a cemetery. When they are done, they cover the fresh grave with straw. I have witnessed the affliction, he begins, hears that he is speaking English, what matter, the affliction of my people, then words clot in his mouth. A few women stand at the doors of their huts as he makes his way through the village.

He is taken by the next wave of soldiers, blindfolded, locked in a stable, where the padre of this place once kept his mules, their bodies decomposing on the path to the desecrated chapel. At times it is deadly silent. At times machine-gun flak or the pop of a grenade. Again he thinks of the black shades in the living room in Rhode Island. His father brought them home from the hardware store, hung them in each of the windows, not to alert the enemy. This memory is an aberration. Or a sin, call it sin, to comfort oneself with the anecdote of how the Germans were chased away, how it was on the radio and in the Providence Journal, even naming the Murphys’ lane that looked down on the bay. Stargazing with his mother in her flannel nightgown, he had watched the Coast Guard scour the heavens, then the depths of the sea, heard the torpedo blast. In the morning Bel lied, a secret with her son, their pact of concealment.

When he is out of this—that is, after the soldiers in the uniforms stamped USA mess the Jesuit up with a kick to the kidneys, bloody his mouth, break his nose, abandon him in the stable, after the archbishop ships him back to San Salvador—Father Murphy will write to his mother that he is enjoying some weeks of R&R. No need to say more when her letter that has followed him miraculously to the Jesuit High School tells him that his father is dead, gone with no warning. Your father’s heart gave out. I buried Murph from the house.We do not rent a commercial parlor.

Bel was right. After her death, he mourns in the rooms of the house with the couch on which his father died and the double bed of her silent departure. Each empty room is haunted by the dead, though when at last he cries it’s for the living, for Rita. When had they set her aside? The little sister at the edge of their story. Rita grown large yet not counted, now bound to her criminal. And the best he could do was scold her, belittle her connection to this Manny, though he knew nothing of love, not for years. Find fault, make fun of her holiday costumes, play the role of sententious brother. Or of the celibate, even now thinking of his useless body, not hers. Why, of all the human wonders we are granted, is it not possible for his sister to lie down with her nameless lover in carnal bliss? The way you talk, Father Joe, since you went off to the seminary. Her big golden boobs in that T-shirt, the smooth, round face twisted with her store of resentment. He stands in the doorway of his sister’s bedroom, a girlish place with a harmless menagerie, the big panda staring him down. I was a child and she was a child, / In this kingdom by the sea, one of Bel’s lines drifts into his head, a poem about love and death by a tortured man. In their innocence they heard only their mother’s way with the rhyme, the swell of her voice passed lightly over the poet’s meaning. Suffer Bel’s little children. Not Rita Murphy. Suffer the old and infirm. When did she leave? Not a day or two ago. More likely she departed the confinements of this house when she was fully accredited to manipulate the bodies of her patients, prop them with canes and crutches—that working life all her own. When had he loved her, if ever, the tag-along sister? Snapping the comic book out of her hands to read out the savvy lines of Dick Tracy. Posing with a cod he fished out of the bay while she tangled her line.

Murph—who’s that? Who’s we who do not rent a commercial parlor? The Murphys of Land’s End. The perfect family of four constructed by Isabel Maher and the patient man who loved her, who heard his wife steal out of bed on winter nights to read. She was a reader way back when she taught at the Maplewood School, and as a girl with her mother, the woman from Ireland who subscribed to The Chatterbox, Christmas books still up in the attic with their old fashioned stories, Bel padding downstairs in her nightgown. Tim setting the thermostat high for her prowling, but would she pull down the blackout shades? On a night when the sirens went off, that was the question kept him tossing until he looked out to the searchlights plowing the sky, heard the squeal of the stair tread, then Joe following her, sensing the night trials of his mother. Those two who read each other without benefit of a book, love their conspiracy. He never wanted his son to be a man neutered by the black cassock. Lost to his mother’s wishes, the boy’s hand dealt. Wasn’t Joe already shepherding one of the faithful back to bed? Only his placid, plump daughter slept through the lights and the siren wailing.

You will be happy to know he died watching the Red Sox.The casket was strewn with flowers Rita picked from my garden. It was a perfect summer day like the day you pitched the no-hitter. He never pitched a no-hitter, only came close. She wrote that her garden was no consolation. He tried to imagine Rita clipping flowers for the bier. His sister disliked their mother’s attention to the garden, Bel’s exasperating care of her roses. Pacing the courtyard of the cathedral in San Salvador, black book in hand, he mourned Tim Murphy, the insurance salesman and perfect father, the good man who rescued Isabel Maher. Wasn’t I the lucky girl? His mother’s lighthearted version, if she spoke of her days in the movies at all. When his calling was determined, his father had asked, Sure it’s your choice? Never saying that his son was about to give over his life, ante up for his mother.

We do not rent.We of the safe haven, Land’s End. Each day for his hour of contemplation in the Spanish colonial courtyard, he turns to Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises. I will call to mind all the sins of my life . . . first to remember the place and house where I lived. They were on the front stoop, Tim Murphy and his son, who had wanted to sign up for the navy. The war was over. The town was building a promenade to run along the shore with a refreshment stand and pavilion. The whole thing will be wiped out in a storm, his father said.

To please him I said, They had better insure it. The little house where we lived was weathered shingle. We sat on the front stoop, which my father made when he brought Bel down from Ansonia, ripping out rotten wood steps with his strong arm, pouring the cement himself in a mold of his making. On the beach below we heard the pylons slapped down and the tires of the lumber truck spinning in the sand. My father said: If their pleasure palace isn’t washed away, our cottage will increase in value for the girls. The girls—my mother and Rita, figuring his daughter would never marry, never move away, and knowing that he would be gone. Next to contemplate your relationship with others. With my father I can remember only this one talk, man to man, his probing to see if I had the spiritual go-ahead for the seminary. His embarrassment, the way he shifted on the stoop to take out a pack of Camels, offer one to me, flip the matchbook, strike the light with one hand like Bogart did in the movies. Sure it’s your choice?

My choice. In Loyola’s discussion of the sin of words, he finds slander, lying, but it’s idle words that best suit Father Murphy’s reply to his father. Idle will do, or unfelt, which the Saint never mentions. He reads the letter from his mother announcing his father’s death when he is assigned to teach in the high school attached to the university in San Salvador, teach English to privileged kids whose parents did not trust Jesuits who might very well be commies, still dealing the best education for their boys. Many will go off to colleges in the States. It is expected that Father José will write stellar recommendations to Georgetown and Notre Dame for the student, son of one of the Fourteen Families who own this country, its land and its people. The boy brings him French brandy from his father’s cellar. Such is his need. It is profitable to make vigorous changes in ourselves against the desolation.

He is back in New York, about to be assigned to a teaching post at Loyola.

“You’re good at math, Father Murphy.”

“My work was in literature, with the poets. . . .” He knows his superior doesn’t give squat for the poets or contemplation.

“That was a while back. What we need at the school . . .”

“I was at Fordham. . . .”

“It’s the youngsters who need us, Father. Our ranks are thin. Math shows up as excellent on your record.”

What record? Scores from the novitiate? GSATs? So math came easy, but he knew the record was the embarrassing politics (not Salvador), the ashram-cum-commune confused in his superior’s programmed head with Woodstock, LSD in the desert and the nights he dropped out, slept over at Anima Mundi, his lapse, his love for Fiona O’Connor, who disappeared, took herself out of his story, for the booze and a widow of sixteen, his house girl who lived with him in Aguileres, who bore a child, not his, out of wedlock. The superior knows perfectly well that many children in Salvador are born without benefit of matrimony—the sacrament of matrimony, this curried man would say, a real gent in his blazer and headmaster rep tie. Father Murphy is now fifty years old. He has been recalled to New York after the murder of Archbishop Romero. On a sunny morning, he went with a group of priests and nuns to the chapel in the hospital where Romero celebrated a Mass for his mother, dead just two days. The murderers wore dark business suits, not their military regalia. Three of them approaching the altar, three shots and Romero was dead. Only one man fired the gun. Later it was said that the mayor, Bobby D’Aubisson, staged a lottery and the lucky man drew the long straw for the privilege of killing the priest who spoke for his landless, impoverished people.

In the wake of this martyrdom, Joseph Murphy, S.J., finds himself reassigned to the province of New York, reclaimed like lost baggage. Best not think he’s unjustly demoted, get into the martyr game. He’s had the love of a beautiful girl and a war, what more does a man need, a cynical thought to put aside. Better to believe that he is perceived as spiritually untalented, like his mother he’s returned to what is granted day by day by day. Math shows up on his record. For a season he is tutored by a young woman with sleek black hair that reminds him of Bel’s in The Silver Screen, a movie magazine hidden in the dark recesses of his mother’s closet. Unlike the sweetheart of the silents, his teacher is awkward, prim at their worktable, an uptight girl in Brooks Brothers suits, floppy foulard ties. A tax lawyer, she comes to an empty schoolroom of Loyola two evenings a week, puts him through his paces. As it turns out, she’s a member of the congregation. Father Murphy is her pro bono. He perseveres in his assignments, testing his obedience, accepts the cloak of humility. One evening, his tutor’s hair is frizzed, uncontrolled. She wears jeans and a sparkler, third finger left hand. He offers his congratulations, and when she smiles—twittery teen—she’s radiant, his mathematician. He holds her hand while she reveals that the lucky man, a litigator, has made junior partner. Then it’s back to algebraic operations, 5x + 6 = 3x + 12, variables and constants, then on to the mystery of negative numbers, but when, as the weeks go by, she moves on to the two-pancake problem, there exists a linear knife bisecting two pancakes:

“It’s simple geometry.”

“Yes, only high school.”

“Easy, but take three pancakes, one knife, unless the centers are collinear.” Her playful hypothesis leaves him behind. “See, there’s no proof.”

“Take the pancakes on faith?”

“Not exactly!”

Her advice when their course is over: “Stick to the books.”

That very summer he begins his work of the next twenty years, his first students repeating courses they’ve failed. He visits his mother and Rita bringing a bottle of sweet non-alcoholic wine. Bel gets the message. Each morning Father Joe walks down the lane before breakfast. His mother leaves him be, steals about the house as though not to interrupt his thoughts. He reads the crumbling pages of Ovid, amuses himself with The Sultan of Swat. In the evening, when they assemble in the dining room no less, with the fuss of gold-rimmed plates and heavy linen napkins, Joe edits his stories of El Salvador, adjusting the horror to network news. Going her rounds each day to the sick and dying, Rita asks how many died in his village. Her throat a bleating red, waiting for his answer and his praise, the chance to say that she too has administered mercy. For the first time he sees the pit of resentment seated in the soft bulk of his sister’s flesh as he gives an estimate of the dead and the missing. It becomes all one on these visits: the body count of nuns and priests, of villagers at El Mazote, Rita’s delicious apple pie. His mother is past seventy, though he believes she fibs about her age, a rearrangement of time dating back to her Hollywood days, acting the girl, a showgirl when she’d grown to a woman, taught school. She asks after his poets as though Donne and Herbert were school chums, inquires into his readings in theology, now that your missionary work is over. He lets her play that game, even while he marks up exams, writes encouraging comments on student papers. Back at Loyola, he speaks of this deception to Father Flynn, his chess-playing buddy, who sets up the board. “Oh, the Jesuit mothers! True believers, you bet.” Flynn sacrifices a pawn to gain some advantage. Joe Murphy contemplates his next move, never speaks of home again.

The books by Bel’s chair are now paperback thrillers, mysteries. The Summer visit—he admires her garden, blue iris by an unconvincing cement pond of his father’s design, roses and peonies blooming. What she has made of a half-acre, her solitary Eden. Land had been taken from the peasants in Salvador for the vast plantations. They were dealt small plots that would not feed a family, yet at times carnations grew in the rich volcanic ash, stray flowers valued for their beauty. Bougainvillea spilled over the wall of the Spanish courtyard of the cathedral where he contemplated the sorry state of his soul, the scarlet blossoms of hibiscus too much for his eyes. Lovely, he says as his mother dusts poison on a delicate rose, genuinely glad that she has this pastime or passion. Bel drives a Chevy, bought cheap from a patient of Rita’s, deceased. There is nothing sad about her, nothing defeated. She drives him to Providence to catch the train back to his classes and walks in Central Park, dinners with an aging, dwindling cast of priests—Flynn, Collins, Massinio, Burns—the occasional treat of steak frite at the bistros newly arrived on Carnegie Hill. So many have left the priesthood since Humanae Vitae, the encyclical carving birth control in Vatican stone, though the Council had voted to revise the church’s position. Still he does not leave the order, though he thinks of the children in shantytowns of Aguileres—sores on their mouths, swollen bellies of malnutrition, their lethargy as they drew the letters of the alphabet in the dust—and of swayback women swollen with the next child and the next. He does not leave because this is what life had in store for him. For a while he believes he will work from within, go up against the Curia, against authority handed down, but that’s all talk with Paul Flynn. He’s check-mated by conservative bishops and cardinals, unable, as his father might have said, to put the money where your mouth is. What money? He is silent, plotting the next clever move though so often defeated by Flynn’s wild gambits that pay off. For a short season he takes up squash, then heart fibrillations kick in, the flutter he will live with for the rest of his life.

He is invited to a screening of the documentary, not yet funded, on the ravages of many wars. Salvador is sandwiched between Vietnam and Iraq’s invasion of Iran. He hears that as a political prisoner he had been hooded by the Nacionales; he sees himself looking hot under the Roman collar, strolling in the Cloisters as though a branch of the Metropolitan Museum with a busload of schoolchildren looking on, was a fit place to bare his soul. The possibility of a communist agenda? As a man of God, the journalist asks. No need for embarrassment, the documentary is never funded. He is more comfortable responding to scholars unraveling the American involvement in Salvador. They are infinitely more knowledgeable about the final offensive, the power of the President to fabricate details of approaching danger, of the State Department’s covert machinations; and as he attempts to answer their questions, he senses the black cloth of the blindfold across his mind. He will tell all that he knows about the alliance of peasants and priests, of the popular struggle and the preference for the poor, but not about the man he should have shriven, or the frail girl, already a widow, who took lovers in his house. He will tell what may be only a story—D’Aubisson having his men draw lots to kill Archbishop Romero, and the anecdote of how the soldiers picked him up wearing the campesino’s rags but he forgot to take off his shoes.

“You see, the peasants had no shoes.”

When he reads what the scholars have written, he can’t recognize himself, denies their account of his heroics. The history of those years passes into the books, truth-telling studies with documented revelations of that prolonged war. Reading of the injury to himself, he thinks of his father wearing a suit on sweltering days so the dead hand tucked easily into a pocket, and of the one-armed stroke he taught his children to swim in the bay, and of Tim Murphy pitching a baseball off balance, yet never telling the story of his wound as an honor or disability, just getting on with life, never marching with the Veterans of Foreign Wars, selling them insurance on their lives, never trading war stories at their picnics.

When he is sixty-five, his mother sends him the watch his grandfather made. A bit testy, he thinks Bel should have given this treasure to him when he was a boy. Now he must screw up his eyes to see the spidery numerals, hold the watch to his ear, a new quirk of Father Joe’s. Its metal case weights down the pocket of the cardigan he wears to class. Though there is a clock on the wall above his desk that sounds the end of each period, he places the watch on his desk to see the hour passing. It is a token of a forgotten time when a man, Patrick Maher at the foundry in Connecticut, figured from scratch the works of wheels and springs, made this useful timepiece with his hands. He listens to its gentle alarm go off at the same moment as the school clock’s liberating raspberry. His watch recalls to him lines by one of his poets, and from the closet with the old books of theology he takes down Thomas Campion’s On a Portable Clock.

Time-teller wrought into a little round

Which count’st the days and nights with watchful sound;

How (when once fixed) with busy wheels dost thou

The twice twelve useful hours drive on and show.

And where I go, go’st with me without strife,

The monitor and ease of fleeting life.

He thinks to send this verse to his mother, then thinks not. It will only encourage her talk of his promise way back when he paraded the love of his contemplative poets, when he had a fastball, fast for high school, when, as a scholastic in the novitiate, he jumped the meaningless hurdle of a standardized test in math. And Bel never reads the likes of Campion. There was her Melville season of memory, the borrowed book by her chair made famous by an excursion to a point of interest—the tired phrase given life by the expectation in her voice.

As they drove out of town in Bel’s gleaming new Buick, she sang. Now, this was news to her kids and Gemma Riccardi. “Toot, Toot, Tootsie (Goodbye)” in a cheery soprano that swung into a series of old popular songs as she tooled down the state highway, which was no more than a two-lane road with a shoulder. Button up your overcoat when the wind is free. Clusters of houses made up small towns with a few stores, then back to farmers’ fields, billboards for Pond’s Lotion and War Bonds, Wheatena, Ivory, everyday fare. Cotrell & Sons, a brick factory by the Pawcatuck, “Take note, Gemma, those wonderful machines print your magazines, Harper’s, McClure’s.” Then, perhaps thinking not your magazines: “Mr. Murphy’s Life, my McCall’s. There are never enough stories!” By the sea, by the sea, by the beautiful sea.

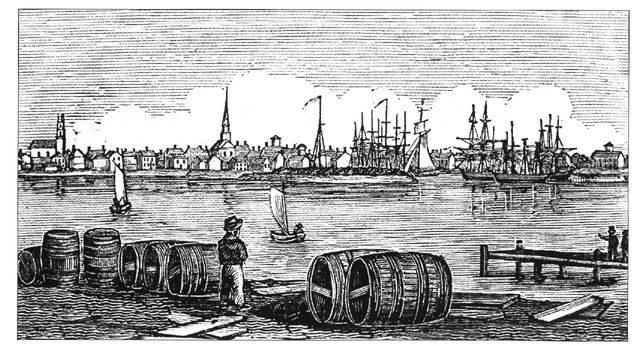

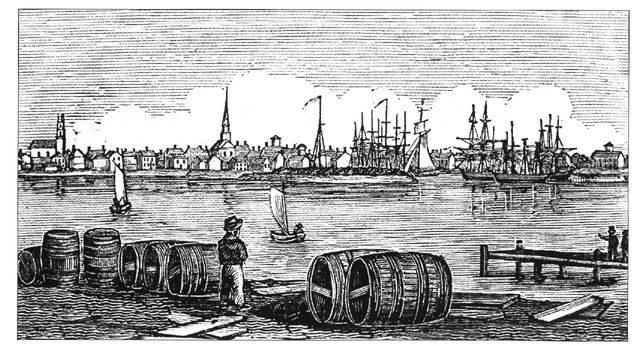

Really going somewhere, they had been prepped, going to visit the chapel in Melville’s book where sailors prayed before they headed off to dangers on the high seas (only Bel has read that adventure), to a site so near, so famous, though how was it famous when Tim Murphy never heard the likes of visiting New Bedford, a sleepy small city on the shore.

“Massachusetts!” Declaring his alarm, as though Bel was heading off with his children to Hindustan, Gay Paree.

“Not the end of the earth,” Bel said, “I’ve mapped the miles.” The map left once again on the kitchen table, so she stopped a state policeman on Route 1, did her charming bit about losing the way, Officer. A big bull-neck man striding over to the Buick from his motorcycle, gleaming black boots, and, don’t you know, pleased to escort the lady with her kids to the Seamen’s Bethel. His hand on the pistol in a leather holster—that was the excitement of the day. The rest, well the rest was finding a small white building in need of paint, the door bolted, then a caretaker come to their aid, a weathered man with a sickle hacking a rim of weeds brought on by the sudden warm weather. He spoke a strange language, which Bel said was Portuguese, but understood this lady wanted to enter the chapel, a cold, musty place with smudged windows, nothing as nice as Holy Name with its stained-glass saints and crucifixion. Rita put a hankie to her nose, the air heavy with mold, but Gemma, reading the plaques with the names of dead sailors—never enough stories—thrilled to any project of Mrs. Murphy’s invention. There was the pulpit like the prow of a ship, and the engraved testimony to the deaths of so many who did not prevail against the perils of the sea.

This is what Joe Murphy will remember when, at last, he reads Moby-Dick: He is a bright scholastic, crackerjack at Latin and rhetoric. He is being schooled to teach, but before he will be allowed total devotion to his poets (he knows his superiors know, that spiritually speaking, Joe Murphy is a borderline case) there’s the whole ten yards of Lit. before he gets to a dissertation—Beowulf to home-grown American classics, and one term it’s Hawthorne’s dark stories and Moby revived. After years of obscurity, admiring scholars are all over Melville and his masterpiece with analogues and sources. All he can think of is Bel, the big book his mother was not reading, the black shades drawn against the enemy, not reading the book that launched the excursions, that season beyond fixed limits. When he is called to prayer he sees not the paneled walls, the high arched windows of Shadowbrook, not Loyola brandishing the cross in the chapel, but the dank Protestant place of no account to Bel’s children, sees her disappointment in Rita thumbing through McCall’s, the homey magazine she’s brought from the car, sees her hope in Gemma Riccardi with her box camera—though what picture worth taking in the dim chapel, after all? Joe sees the spot not as instructed in the first exercise of Loyola to visualize Christ scolding the moneylenders or healing the leper, never gets to the jangle of coins in the temple or suppurating sores—sees the chill Protestant walls, hears his mother’s voice cracking as she reads Melville out loud in New Bedford, then her repeat of a line, a quick recovery. She’s a trouper, script in hand, reading from the book renewed again and again from the library. She tells her children and Gemma, Never fear when you don’t understand, confesses she once lost interest in the difficult work, then read she does, skipping about, but there are no dull parts. He experiences his first flush of discomfort, then awe sets in as words spill at him, as they settle to her performance while the Portuguese custodian stands by the side of the pulpit with his scythe, a grim reaper. Better to see the page—Bel threw aside a green felt hat with a bill that shaded her eyes—better to play to the children, her voice inflated with Melville’s words, Methinks my body is but the lees of my better being. . . . Lees? Yes, the world’s a ship on its passage out and so forth, a disturbing show. They did not want to know this about her, that she seemed, well, kind of nuts reading from a famous book for three kids in a row who could not meet her expectation of an audience. Had she brought them to this musty place hung with names of the dead to show them her cap and trench coat were not up to the performance? Many years later, her son reading Melville, would recall his mother exposing herself as an actress, her desperation as she slapped the book closed. Pricked with reality, she came down, down, down, put on her hat and shrugged, “Well?” Begging their review. Her costume, her delivery?

“Well?” A question never answered—not by Joe when he put on the amice, recalling the blindfold soldiers tied over Christ’s eyes, performing the proper rituals until he ended up at Anima Mundi, where that communal life chucked the trappings of authority for their priest done up as a Buddhist in a saffron T-shirt—not in the humble costume prescribed by Archbishop Grande to be one with his people; not answered at his mother’s funeral in the chasuble chosen as though out of wardrobe, penitent purple for the theater of the moment in an empty church. Well? Perhaps answered by Gemma—given to piracy and flamboyant disguises, nothing so modest as a perky green hat or seductive as pearls falling on the breast of a star in a silver gown. Well? Answered at last by Rita, her tart replies to Joe after a lifetime of silence, her pluck driving off to points unknown in the costume of a clown. Well, Father Joe, what do you think of my show?

No answer, but on the day of Bel’s theatrics in the Seamen’s Bethel, there was only the stunned look of three kids at a middle-aged woman carrying on as though on the stage of a Bijou, their wondering faces seen, really seen by her son, who goes back to his cell eager to get at Moby-Dick; or The Whale, but distracted by the memory of his mother’s excursion, Spring 1943. Sharp recall of Gemma’s murky photos. One, a carved wooden plaque:

In Memory of

Jorge Montera lost at sea

Steward of the Whaler Ambrosia

In the North Atlantic, October, 1933

The other, his mother lolling against the lucky Buick, though the day had its misfortunes. They must wait by the side of the road, Yes, we have no bananas, while a convoy of jeeps and open trucks passed them by, personnel being moved to a port of debarkation, waiting impatiently with the lure of Howard Johnson’s frankforts and twenty-eight flavors on the other side of the King’s Highway, the convoy trailing on and on, so only time for a pit stop, popcorn and soda, It’s only a paper moon, the dark coming on, the gas gauge wavering toward empty when Bel let Gemma off at her house on Cotrell Street, “Thanks for the ride.”

But home in time for supper, Tim Murphy discarding the evening paper, embracing his family as though they’d been where? Timbuktu, not New Bedford. As his son, in the discomfort of his student chair, finally opened Moby-Dick, burning the midnight oil in the Berkshires, he could do as Loyola bid, visualize the rewards for their pilgrimage, cube steaks, Rita’s favorite Franco-American spaghetti, and recall from the dregs of his being the betrayal, wasn’t that part of the deal? Hearing Bel proclaim Melville’s fierce sentences, he had prayed, Let her stop the dramatics. Dear God, let my mother be ordinary. Why, as the Saint asked, has the earth not opened up and swallowed me?

The Murphys’ house and its contents sold to Damien Forché, the fashion photographer. Father Joe’s heart thumps into its arrhythmia as he waits at the kitchen table reading once again the arrangements. For the signing of papers, he wears the seersucker suit and a narrow knit tie, a straggler in his father’s empty closet. His canvas sports bag zipped to go. It has been less than a week since his mother’s death. He has wandered the small rooms, slept in his boyhood bed, walked down the lane as of old, breviary in hand. The girl who came to Bel’s funeral runs out to meet him each morning modestly dressed, what a back number to think that, the sweet thing scrubbed clean, her face brown from the sun, generic pretty, blond, blue-eyed, the twitch of her uncertain smile.

“Joe,” she calls, told to discard Father first day.

“Pet?” Her name, Pet, and she is that, a golden pup of a girl nipping at his contemplation. Not seeking the role, he has become her confessor. Pet, a model, celebrated, though he has never seen her on the cover of Elle or Vogue. Pet, strangely alone in her summer rental.

“She was like kind,” Pet says. “We talked, you know, it was only a few days. I mean, your mother, I didn’t know she was gonna die.”

What was like kind those few days? Bel listening to the girl’s story, how Pet had come to this newly discovered town with a purpose, how she had rented down the lane and found Mrs. Murphy still sleeping in a rocker when her house had been sold to Damien Forché. Before it is portioned out, he gets hold of her story, that the man had been her lover, how Damien wasn’t into real estate and how she had this arrangement with him, you know, casting her eyes down, an arrangement, how Damien was swift, made her like famous—her face, her body. How they traveled together. Latvia, Kenya, a shoot on the Isle of Man.

“Rome?” she asked. “Ever seen Rome?”

No, though the week before she died his mother told Pet he would be sent to the Eternal City for his studies. Grant Bel her shopworn dream, for after all, she listened to the pathetic tale of this girl, whose limbs had been sanded, painted, primed, whatever they did to her breasts, thighs and that sweet face for the camera.

“It was like Mrs. Murphy knew I was celeb. Like you said in church, from her time in old movies.”

He did not believe it was like. Under her bronze skin Pet looked washed out, celeb glossed with cosmetic health. How easily she cried and tried not to. As they walked together to the end of the lane, the serial of her sad love story was interrupted with news of the Mangiones’ house, in which a popular novelist now lived, of the Dunns’ renovated by an anchorman, NBC. He had not noticed, as blind to the stunning renovations of Safe Haven, Done Roamin’ as he was to fashion on Madison Avenue. So—they were both waiting for this Damien Forché to claim his prize, the shingle cottage. Each morning Father Joe spoke to Pet of the vagaries of the human heart, the power of love to forge connection. How you talk, Father Joe, since you went off to the seminary. His sister’s admonition in mind as he worked at his pastoral role. And where was Rita now? Registering in a false name, a motel stop on her way to a husband with a deleted history? Or had she already arrived at address unknown?

“Where you from, Pet?”

“Springfield, Illinois.”

After the morning consolation of this lovesick child, he walks through the rooms of the house—Were they always this small?—dazed by the passing of this fragile family life so carefully constructed. He wants nothing, not his catcher’s mitt or the Gallic Wars, certainly not the sanitized letters written to his parents, then to his widowed mother from Salvador. He riffles through Bel’s closet for the movie magazine with her picture, always stashed beneath a moth-eaten shawl Maeve Maher brought from Ireland. The forbidden text gone, but there’s a puzzling tin skeleton rusted at the joints, and the road map with the inked route of each excursion, the blue veins of his mother’s enrichment program. No longer her bright boy, yet he recalls the grand staircase of Mark Twain’s house in Hartford, the mahogany porch, the fancy furnishings of a boy from Hannibal, the mother of all pool tables and Twain’s failed typesetter inhabiting a lofty upper room. She never came close to the Melville performance, just said how they should read the adventures of Huck if they hadn’t, and wasn’t it something that he wrote about the Mississippi right here in Hartford, so close to home. That was her theme, close to home, the Greek Revival arcade in Providence, with its quaint shops under glass—so Parisian; the mansions of Newport—the Corinthian columns of Marble House, the Great Hall of The Breakers—Do you think the Vanderbilts had fun? Bel driving off with her crew, leaving home for the Pier at Narragansett, closed for the duration of the war, a bucket of fried clams to stave off disappointment. Dipping into the ketchup, her son, missing school and baseball practice, wondered, What’s wrong with staying home? The blowout at a railroad crossing after the carousel at Watch Hill—for kiddies, what was Bel thinking?—bumping across the track on the rim, shredding the tire. There’s a long, long trail a-winding, her plaintive song while he rolled out the spare. He was thirteen years old, jacking up the Buick, the work of a man.

Not home in time for supper. “You’re lucky to be alive.” Tim Murphy pounded the kitchen table. A cup spun to the floor, shattered, one of Maeve’s teacups from Ansonia. Where to place the blame? It was referred to as the accident, soon forgotten, or maybe it was Spring, daffodils fading, baseball in earnest—the excursions came to an end. Bel sacrificed a plot of roses to grow tomatoes, squash, peppers, settled into a Victory Garden. Father Murphy, deed to the house in hand, figures that was it, the season of discontent passed. His mother settled.

“You’re the prêtre.” Damien Forché, come in the front door, found him dreaming. Forché in black—silk and leather—top to toe. Shaved head gleaming above a clever face, nose and mouth sharp-edged, eyes scanning the location, retro American kitchen—Formica, metal dish rack, leatherette chairs, Aunt Jemima cookie jar. “Wow!” Moving about the set, taking possession, a touch to Rita’s embroidered dishtowel, the frayed cord of the pop-up toaster. “The prêtre. Well, hellooo, Father!”

To Joe Murphy it rings like the refrain of one of his mother’s favorite musicals, cheery and false.

“Hell of a situation, view of the bay. Prime. You travel the East Coast, how many, I mean, shorefront properties aren’t crapped up with condos?”

“Not many, I suppose.”

“You got it. Now, this is Carlo.” Carrying in the equipment, Carlo. “Vintage Hasselblad, Stereo Realist in there you wouldn’t want to leave in the car.”

“The lane has always been safe.”

“Always isn’t now. Nothing in the car, Carlo.”

Carlo, a choirboy, soft cheeks, rosy mouth. Joe Murphy, prêtre, sees him in a white surplice, the apple of many a priest’s eye. Underage, still in that category? Carlo this year’s celeb? There’s a good deal of touchy-feely butt tagging while Carlo stows the equipment in the pantry. Yes, there is a pantry with the last jars of Rita’s apple butter, strawberry jam.

“Cute,” Carlo says, “is very cute.”

The Murphy house with all the old furniture is to be photographed black and white.

“Before and Aft. Documentation. Print to the family.”

“I am the family.” Joe holds out the papers to be signed.

“So when we do the story. Stick around. Take. Take whatever.”

“After you shoot?”

“You got it. Stick around. I mean, no hurry. Sorry about the noise, they start drilling for the pool. Carlo likes a lap pool. Stay in shape. You got that wasteland out back.”

“The garden?”

Damien Forché is not limited to fashion ops. “Scotland, Louisville, Provence, maybe fifty gardens.” He has produced maybe fifty gardens, cut the ultraviolet light, filter the haze. “A pool you get the flora droppings. Bluestone the grass. This whole garden thing’s had its run, twenty years—lilies, lavender, bugloss. Parterre. Japonaise. Basta hosta. Bluestone to the garage.”

“There is no room for a garage.” Joe speaking as to a child.

Before and Aft. The cottage overlooking the bay is a tear-down, an expression new to a prêtre not into real estate. Neither is Damien Forché into it. He’s on the road, click-a-dee-click, but with a keen eye for a growth investment. In place of the cottage, a tower, three stories, get the prime view, lots of glass. Shingle, stick with the vernacular. The garage goes urban, underground, bike rack, mini-gym, stay in shape.

“Leave the hedge, totally Hamptons.” Forché unrolls the architect’s plan, weights it with the Belleek teapot so light it skims across the table. Joe clasps it to his breast. It is the only thing he means to take with him, the teapot from Ireland, and, yes, the cigar box with his father’s honorable discharge and the letter with tear blots in his mother’s hand. He holds out the agreement, the last page to be signed, relinquishing furniture and personal possessions.

“If you will be so kind.”

“Finalize, you bet. Where’s the notary?”

The notary? He’s been living out of the world too many years. A trip to town in the open Corvette, Carlo shouting at the low brick and clapboard buildings on Main Street, “Cool, is so . . . ,” cool erased by sea breeze. When all was signed and sealed in the Pawtucket Bank & Trust, Joseph Murphy having affixed S.J. to his name, legal or not, thought to leave on the next train. He has his sports bag with Tim’s cigar box, Bel’s teapot rolled in his black suit, but feels beholden to Pet, his pastoral duty. He turns down a ride on the pretense he has some business in town. A digital display over the bank reads July 9, 12:00, 95°F. 35°C. Forché sucking up the heat.

Presuming these are his parting words to the fashion photographer, Joe says, “Consider light-colored garments.”

“Padre Simpatico, you know who grew up in this town? Riccardi, that’s who.”

“Gemma. We graduated from high school together.”

“That is totally amazing. Know where she lived?”

“I have no idea.”

Riccardi is essential, grand duchess. Her series of the clapboard two-family house she grew up in. Wow, fifty years ago, secondhand Leica M4-2, is totally sad, totally beautiful. Move in close with the rangefinder, you gotta be a genius. The great late period: absence of material content, totally void. If Damien Forché had that talent and so forth, fuck commercial. A disciple of Riccardi, Queen of Tarts. 12:05. Joe Murphy enduring a lecture in the parking lot of Pawtucket Trust, loosens his father’s tie. Padre, prêtre, feels the steamy pavement through his shoes. He will walk back to the lane, as he did each time he came on his visits. The town has smartened up, it’s true. Espresso and T-shirts silk-screened with pictures of the pier, antiques shops, Brandle’s soda fountain done up as Café Venezia. The trek home, not home, in the heat is exhausting—past the New England granite of Holy Name, past the rectory, its squat tower aspiring heavenward, past the yellow brick grammar school, sites which seem fixed, if not immortal. When he arrives at the lane looking over the bay, he knocks on the Pinchots’ door. Mrs. Pinchot delivered him on a hot Summer day, helped him out of his mother’s womb, that was the bloody story. Pet comes to the door. Empty of tears, her waxen prettiness dissolved, sallow flesh melts under blank eyes. Lifeless straw hair. Yes, she saw him drive by with Carlo. He was like speeding to get to the house now so totally his. Her nameless tormentor. She knows Carlo from the Armani ads, the Versace runway in Milan. From the bus posters, Calvin Klein. Like androgynous. She’d been a fool and run after them, ran round the high hedge, he (Forché) swiveling away from her, his swift backward smile dismissing her as he dismissed his models at the end of a shoot.

The priest has come to tell her she must leave this place.

“The old lady, that’s what she said. She said go home. That’s what I did, only home was Connecticut, not Illinois.”

Cotrell Street runs off the end of Pleasant, the end that runs into Price Chopper Plaza, with the dollar store, a Laundromat, Mc-Donald’s. Cotrell is a distance from the lane overlooking the bay. Gemma Riccardi ran it in ten minutes when she was a girl, ran to the Murphys’. It takes Father Joe a half hour by the workman’s watch, stopping to rest in the heat on the steps of Holy Name and again on a bench fixed to the sidewalk in front of Handmaiden, its shopwindow displaying a three-masted ship in a bottle, ceramics and baskets by local artists. Cotrell is two-family houses built in the Twenties, respectable rents afforded by millworkers, mostly new immigrants. He had thought to call ahead, but Pet, reduced to tears, could not find a local telephone book. He has no notion if Gemma will be at that house on Cotrell but thinks there’s a chance, while there’s little hope of finding Rita, thinks how odd that he’s tracking down women, first the sorry girl, now the icon, totally genius, that Gemma. Odd, but what’s off the game board is his firm decision to stay in town, not slink back to his summer course at Loyola. At long last, the mule not choosing the way. Dizzy with the heat, it occurs to Joe now, or was it when leaving the lane for the last time, that his superior will recommend psychological counseling given his bereavement. He knows the doctor on 96th Street who will not cite him for disloyalty to the order, will not remind him of his vows. Depressed, deranged, perhaps the many deaths witnessed in Salvador never dealt with, and now? Now he reaches for a handkerchief to mop his brow, finds the skeleton in his pocket.

Now my mother has gone to her heavenly rest, her reward.

He knows the doctor, confessor to priests who damage little boys, a worldly man who quotes Augustine’s confessions easy as accessing Freud.

I am less certain of my calling.

Only less certain? Not exactly a revelation on the road to Damascus, this long festering of doubt. He will not mention Rita, not give her away. He must be at liberty to find her. Reparation is now his calling.

We all live with uncertainty.

Let’s not argue the point. This heroic retort plays well as he heads down Cotrell, what may still be Gemma’s street.

Dunphy inscribed on a tarnished nameplate. He remembers about the Dunphys, not much. Memory calls up a fussy small-boned woman in the shadow of her daughter. Who really cared about the parents of classmates in the self-enclosure of adolescence? He knows this from the kids at Loyola—doctor, lawyer, merchant chief, custodian. Dunphy, a bookkeeper at the mill?

But here’s Gemma, larger than life.

“Joe, you’re a shambles.”

“What’s left of me.”

What’s left of Joe Murphy is a backroom boarder sort of man, a quiet fellow coming and going through the cluttered rooms of Gemma Riccardi’s house. He has moved beyond less certain, is much occupied with the first anxious step to leave the priesthood. They will not keep him on, a teacher of math at Loyola. He has never sought work in the world. Can he live without privilege? That’s what it’s been—the boy, the man set apart, in no need of intimacy, not with family or his fellows, Bishop Grande plotting his ministry in Salvador, Paul Flynn allowing himself a second beer over his next move, always the chessboard between them, their talk guarded. Padre, granting absolution for the campesinos’ sins, spirited away from their shanties to the safety of the classroom. His birthday passing without notice, he is now seventy-two years old, a man with a fragile teapot, cigar box, tin skeleton, workman’s watch.

Flynn is called in this moment of crisis. “It has a name, Joe, accidie, a sort of spiritual melancholy, loss of grace. A little too late to quit, Joe. Take early retirement. Play golf. Permanent retreat.”

“Be taken care of?”

“It’s like getting a divorce,” Gemma says, having twice signed on that dotted line. Riccardi professes to live in the present, cooks hearty meals, tends to the small plot of lettuce, herbs, the tomatoes Bel advised. It’s pleasant having a boarder, though Joe is often glum. Stuck in the past, his talk sounds to her like faulty translation, or jacket copy spilling the beans without the full story. Or the hidden details of a negative. In fact, she finds him undeveloped. This man with the full head of gray hair and set jaw is scared to death of his shadow, scared there might be someone still there. He once loved a girl—well my goodness! And solaced himself with the bottle. Cowardly lion, while she’s in need of a heart, hers numb as the tough nut of her ambition. And there is the missing child, Rita, sullen in the back of the Buick studying her lady magazines, the chubbette lurking in her bedroom while she turned the earth in Bel’s garden. Rita is somewhere baking pies for her husband—granite counters, Cuisinart, no trace of the dumpy kitchen on the lane. Working in the darkroom of the Riccardi-Dunphy kitchen, Gemma invents the rewards of Rita’s disappearance. She develops the film shot during the day when she prowls the neighborhood in a caftan, gift of the Minister of Tourism, Morocco. (National Geographic—sand ripples, camels, mounds of dates and figs in the bazaar—Kodak color Land 55). The days come on hot and humid, so she wears the caftan with gold braid to the amusement of her neighbors, the Wakowskis. She writes down their names, Sue and Henry. They sit on the front porch for their picture with Sandy, mixed breed. And the kids running naked in the spray of a fountain and the grizzled vet with the track marks running up to the dragon tattoo of his outfit in Nam and the pierced poet chalking the sidewalk with verses. And Joe, she takes him in a moment when he looks up from his papers, startled as an animal new to the zoo, then he smiles to please her and she snaps him again.

She will not go near Land’s End to report on the demolition. “Spare me the kudos of Damien Forché.” Riccardi taking her pictures, her gift or limitation. Hometown, nothing fancy, nothing new, which after all is her signature. The plot of earth with the first picking of basil, the hard green tomatoes keep her in one place for the season. Who would have thought it would be the Murphy girl got away? Not a question to put to Joe, heavy with this loss when he should be mourning his mother. He’s launched himself into a detective story to track Rita, married to a squealer, imagine! A shotgun wedding, that Rita unable to testify against her husband, the lucky couple packed away. Gemma never asks her boarder how long he will stay or what he’s up to in Phil Dunphy’s bedroom. She doesn’t expect a little brown envelope with the weekly payment. In the evening, she sets their places at the kitchen table with the oddments left behind by renters she never set eyes on. Her glass of wine, his iced tea. The upper floor is now empty, and she thinks to settle Joe in a place of his own. He has never been on his own, passed from his mother to Mother Church. In Salvador there were poor women to wash and cook for the gringo sent to save them. Then again, she likes to come in from taking her pictures, from weeding the garden to find him writing whatever he writes to the authorities that run his life, and to the office of the U.S. Attorney begging for news of Rita. Plea bargaining, she calls it.

What he’s up to: writing on Gemma’s laptop to his Provincial in New York, that’s one project, a letter of his departure from the Society rewritten each day, which will be sent, he vows it. Writing to the U.S. Attorney in Providence, he uses S.J., Rita always in mind, the wife of Manuel Salgado, the union boss who ratted on his partners in crime. Somewhere in the fifty states, Rita is monitored by a U.S. marshal to assure she has contact with family in the eventuality of crisis or death. When he arrives at the State House, he is shown into the upper reaches, which look over a city all new to him, an impressive mall, the river buttressed by a highway, in the distance the gilded dome of the Old Stone Bank. Bel had parked right in front, and they’d watched students in sculls racing down-river, then crossed the bridge and found the Arcade with sad little shops—tobacco store, shoe repair, millinery. His mother had made them climb to the top. There was no view, just a dirty glass ceiling. Nevertheless, an excursion. He takes his workman’s watch out of his pocket, black suit today, wonders if it is part of the game, keeping him waiting, time to consider he’s an old fool.

“We took a chance, you know.” This from the assigned contact, an assistant state’s attorney who looks twelve to Father Murphy, flustered going up against a priest. “A chance letting the wife stay behind. We understand the crisis is over, that is . . .” At a loss for words.

“The death of our mother?”

“Well, yes.”

“So I must wait for another crisis?”

“A medical event, it would have to be major. In a federal case, we get reports from the marshal. Of course, they could come out of the program, the Salgados. It happens if a party can’t adjust to the situation.”

“What sort of gamble would that be, reverting to Rita, to Salgado?”

The attorney offers no answer, contemplates the mall, swirling letters—Lord & Taylor, Sears. “Could be the climate, the change. Times, they’re lonely.”

Joe endures a long moment of silence, then asks, “The charges? What do you have on this Manny?”

“It’s not nice.”

“Beyond fraud, extortion?”

“Nothing to tell you. Forgive me, Father.”

“No need. It’s your job. We are in the same confidence game.”

He finds the Salgado children. No problem for the contact giving those names, though the son has been legally Brett for some years. He grants the priest an appointment, not his office, his home on Saturday, gives directions to a gated community on the Connecticut shore. Joe Murphy last drove a VW bus in Aguileres, before its tires were stolen. He fears death from a semi tailing him on I-95. He scoots out of control drawing up to Brett’s mega house, sets off an alarm. Manny’s son steps onto the circular drive to speak with this old party rutting his perfect lawn, prying.

A trim middle-aged man, wound tight, small as a jockey, Mr. Brett is scrappy, “It’s actually none of your business. Have you ever lived with a fuckup for a father? A turncoat?”

Joe can’t say that he has, but notes turncoat and the Boston College sweatshirt. Brett is an educated man, his harangue of sharp words carefully chosen to address this priest who might have taught him. It’s good riddance to Manny wherever he is. “I’m not without sympathy for your situation. If you’d like a second opinion, call my sister.”

He leaves Father Murphy in the scalding sun of the driveway, returns with the telephone number written on his card—

Anthony Brett INVESTMENTS •REAL ESTATE •INSURANCE

A curious Mrs. Brett now stands in the enormous double doors of her house, doors fit for a church on a New England green. She is wrapped in a towel, still dripping from the pool. Stays in shape, Joe thinks, wiry body, a sharp nose sniffing out fear. A vagrant, a beggar come to her door, seedy old man unsteady on his feet, a threat to their comfortable life, to their disconnect from Manny. As he pulls away in Gemma’s rental, he gets Brett in the rearview mirror, stroking the ground, healing the tire tracks in his lawn. The interview has taken less than five minutes, Joe checking his watch against the clock on the dashboard set for another lease, another season.

He calls Mimi Salgado at Bon Soir, in Boca Raton. Two phones: one for the boutique, one unlisted. When the phone rings, the one she dreads, she leaves a good customer trying on satin sailor pants that won’t zip. She hangs up on the man who’s calling. When she answers again, Mimi whispers, “Father who?”

“Murphy. It’s about Rita, my sister.”

“I don’t know any Rita.”

“The woman who married your father.”

“That slut? Killed my mother.”

She slaps down the phone. Pooch yaps in his little bassinette made for a doll. He knows when his mistress is upset, but does not stir from his nest. Visibly shaken, Mimi prays, Jesus, protect the dear one, smooths the Yorkie’s topknot, goes back to her business with a woman from Venezuela whose husband got the money out in time. Mimi suggests ghetto jeans that are fashionably baggy, parachute silk in an 8, vanity sizing.

When the phone rings again, she lets it ring, dear Jesus, finally answers.

“Killed?” The man’s voice unsteady, choking back sobs, “Killed, killed?”

Mimi hisses into the mouthpiece, “I meant with the goddamn massage, the manipulation. I don’t care the doctor sent Rita. Leave her in peace.”

“The massage?”

“Leave my mother in peace. She was dying.”

Pooch is licking her hand, soft laps of love, holy Jesus.

The customer is thirty years too old for the parachute jeans. Very expensive, half the thrill of the sale. Not today. Today Mimi turns CLOSED on the door of Bon Soir, calls her brother.

“He’s nothing,” Tony says.

“So you gave him my number!”

“A sick old priest. It’s a pathetic situation.”

Not pathetic, she takes no comfort in her brother’s cool consolation. Tragic’s the word, always the men waiting for her father. Cops circling the block. Little Manny with his buddies. When they were kids, they knew those guys were protection. Let them be blotted out of the book of the living. The neighbors knew, and her mother. Her father was a neat small man, dressy, that’s where she gets the style, not from her mother, who married a fisherman wanting a simple life, not brick facing, three car garage, mink and the Elsa Perreti. Her mother prayed for Tony to go into the law, to have law on her side. That didn’t work out; after BC with the priests, he threw in with his father.

“How’s the pooch?” Tony asks. They have little to say to each other.

“She’s the best.” The best little doggie, her gift from God, with little wet nose sniffing her tearstained cheek.