III

Dog Days

Let faith oust fact; let fancy oust memory;

I look deep down and do believe.

—Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

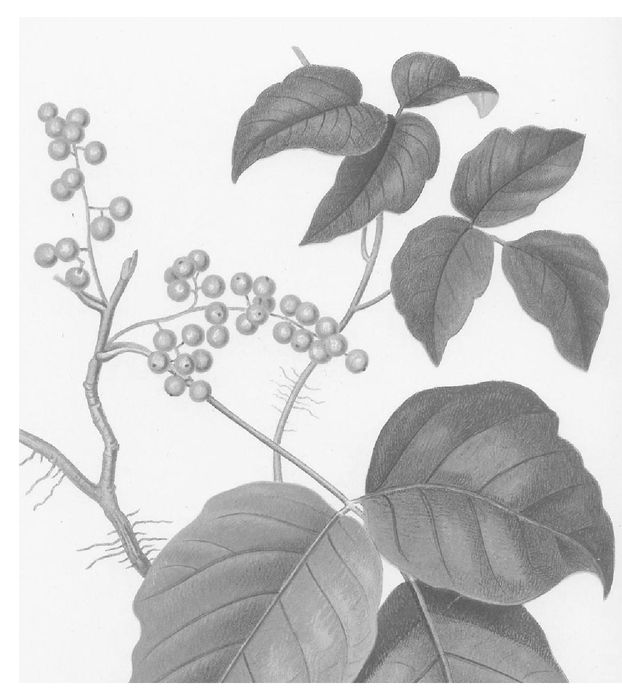

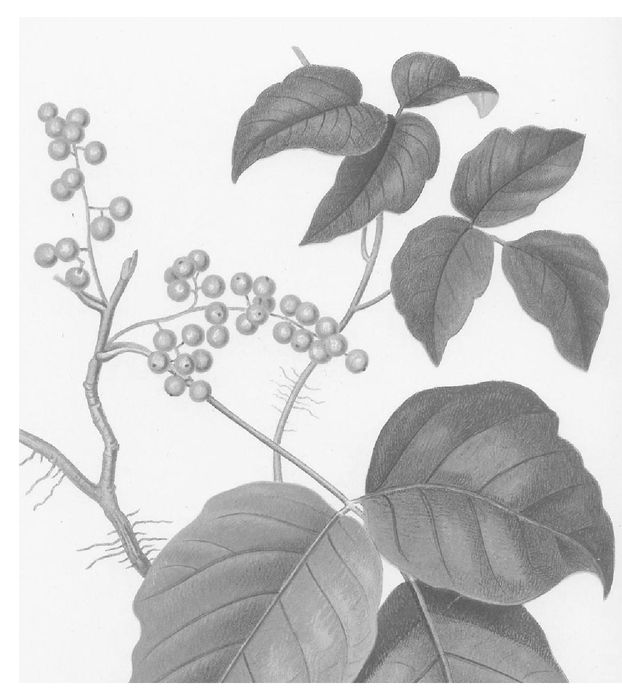

Rhus Toxicodendron

Tomatoes hang heavy in Gemma Riccardi’s garden, hard and warm to the touch, still green as she stakes them. Perhaps planted too late to ripen. She takes their hard pale skin as a sign that she will fail again, this time as a gardener, though the basil is coming on bushy, the lettuce perfect as the tender leaves you might buy at a farmer’s market. It’s hotter than she remembers this town on the bay. The Wakowskis have said she must water early or late, not in the heat of the day, so she’s in the muddy compost with a hose, seven-thirty, not every morning.

Overwater and your crop will have no taste.

What crop? Who’s she kidding? When she turns to the house, she sees the empty eyes of the windows upstairs and the shade pulled in the back bedroom. On the day that Joe Murphy left, she did the strangest thing, pushed Dunphy’s bed and dresser aside, moved her equipment in, pulled the shade, never in her life felt so lonely. It’s hotter than hell in there, and the heat speeds up the developing bath, prints with no depth, no contrast. The expense of an air conditioner means nothing to Riccardi, it’s as though she’s bound to stick it out for more than a few leaves of lettuce and hard green tomatoes, for control over the photos she’s taking of life on Cotrell Street, once her home.

Pet (Elizabeth Strumm) stands in a tangle of poison ivy at the break in the old lady’s hedge. The shingle cottage is gone. From the picture window of her rented house, she has watched its roof and walls being carted away in Dumpsters, hunks of plaster with strips of wallpaper flapping, sinks and toilets disemboweled, battered doors rent from their hinges. The place cleaned out by Goodwill before the demolition, the trophy of a stuffed panda tied to the hood of the yellow van. Pet knows she should pack up and leave, but stays on, punishing herself with a glimpse of the black convertible, Forché at the wheel in baseball cap, Carlo greased for the sun. Now they have departed. Why has she come to the old lady’s garden in this heat without shelter? She lives alone with bits of wicker furniture, a lumpy sofa, like Goldilocks tries out each ill-fitting bed. The mismatched plates and spoons, totally grungy, belong to no one, summer rental stuff. Pet, who is not a reader, thumbs through the discarded best sellers and guide to the sights of Rhode Island. A picture book of Ferraris, Maseratis with the name Ricky Pinchot in a sloppy boy’s hand, and a Fannie Farmer Cookbook stained with chocolate and translucent splotches of butter, seem to Pet totally sad.

Her red MG sits in the driveway. Surely he must have seen it. In town she buys Doodles and Fritos, frozen enchiladas, Häagen-Dazs Cookies ’n Cream and a fifth of Stoli. As she gobbles forbidden goodies, Liz Strumm of Springfield, Illinois, suspects this life day by day without will is called maybe Clinical Depression. It’s an effort to slip in a CD, someone’s Motown or bebop or Schumann, an effort to turn off the hours of daytime TV. Time melts in this heat like that sick watch of Dalí’s. Her thighs bulge in Comme Des Garçons jeans, breasts pop her Armani jacket. In the mirror she sees herself like, exactly like in the high school yearbook, corn fed, ripe for the picking; a robust American girl no prize for the runway or the cruel lens of Damien Forché. The house is sticky, stifling. Not to hear the noise of destruction, she shuts the windows tight till the wreckers finish their day. At night she sleeps a drenched sleep without drugs. In her gear, a model’s vast store of expensive creams, paints and dyes, Pet that was has a supply of candy that might make her happy—Zoloft, Prozac. To pop one, just one, would be an act of will, a step in some direction. The trucks grind past her window, heavy with rubble at the end of the day.

Then it is quiet. A day of rest, Sunday? TV says that the temperature throughout Southern New England is ten degrees above normal. Flipping along in flipflops, Liz walks down the lane in the blast of midday. Far below she sees the beach is crowded, little ant people stirring up the water, scrambling in the sand. This is healthy, walking as she did to the old lady, walking with Joe, who listened to her sob story, that’s what it was, total girl-grief. The silence of the day has calmed if not cured her. She stands in the break in the hedge, viewing the empty half-acre lot. There is nothing, not a tree or flower, not a shingle or splinter of glass, a hole in the ground where once a cellar. Liz does not trespass, just looks on as though this scene of devastation is framed, picture of war zone. But there is a cement wound in the earth, long and narrow, with stones placed round it like graves where the bodies are buried.

As she turns to run away, her flipflops come off in the thicket of poison ivy. “Leaflets three, let it be,” Liz remembers from Girl Scouts, and runs barefoot back up Land’s End. In the bathroom of her rented house she scours her ankles and feet with an ancient cake of laundry soap, a comforting self-flagellation, then anoints the scraped flesh with the dregs of the bottle of Stoli. That should do it, but driving through the night, when she is more than halfway to Springfield, the prickle begins, the rash flames. How long had she looked on at that desolate scene in Rhode Island? Time enough for the oils of Rhus toxicodendron to bond with her skin. She draws off the interstate at Columbus, tries to sleep by the side of the road. In an all-night drugstore in Dayton she buys peanut-butter cups, calamine and Vogue, the September issue, out early as always, with Pet (no last name) on the cover, wearing a glen-plaid bustier, Queen of Scots as classy rocker. One blond tress hangs to the meager mound of her right breast, wind fans the rest of her ironed hair to the sky. It had taken all day to get that shot, one of maybe hundreds. Hands on hips, pelvis tilted to right, to left, center forward, a pose he discarded. Her left hand idles at the lacing of the plaid contraption, itchy under the studio lights, while the right arm, sporting a Celtic bracelet, is flung aloft: daring, free spirit. Pet flaunts her chill touch-me-not smile on a million and a half Vogues. She buys three, cleans out the store. At this checkout counter no one will see her. The lens capped, end of a grueling session, the shuttered look of his eyes. It was like he’d stolen her soul with the camera. Dawn in the shopping plaza. A man with a jug of milk, a jumbo pack of diapers takes off in his SUV. Liz Strumm plunks herself down on a dewy island with struggling petunias, screws the top off the calamine, dabs at her raw feet and ankles. The blisters are weeping.

She drives out of Eastern Standard Time at the Illinois state line and on through Urbana-Champaign, where she should have learned her lesson. She has gained an hour, may be home in time for supper.

Paul Flynn opens the chessboard, sets out the men. He is on the roof of the lower school, fitted out with a jungle gym and swings. The city is trapped in a heat wave, a brownout sucks the cool from the air-conditioned buildings of Loyola. The long summer daylight exposes the priest to his neighbors. Waiting for dark, he’s brought vigil lights up from the chapel, cold beers and cans of Pepsi in a bucket. Waiting for Joe Murphy, who said he was up for a game, but said little else about the death of his mother. The silence of their play is always punctuated by groans at a stupid move, yelps of triumph. Perhaps there will be a moment to ask after the sister left alone in Rhode Island or the details of the burial. Joe has been away for more than a visit, and their only conversation was that blip on the phone, nonsense about leaving the order. He’s sorry he made light of his friend’s despair—retire, play golf. Weeks left of the Summer, he will propose they do a stretch of the Appalachian Trail. Perhaps one he’s hiked before, the easy stretch in the Berkshires short of Mount Greylock. By his count, Paul Flynn has done a good half of the A.T., has plans for the Blue Ridge to Harpers Ferry where the Shenandoah and the Potomac cross, worth a voyage across the Atlantic—Jefferson, quoted to his class, who fake interest in Whistling Gap, Big Bald, Devil’s Pulpit, the friendly shelters of the Trail, midges, cow pies. He’ll stick the Summer out with Murph, stop short of Greylock, the mountain too high for Joe’s trick heart. Below, the clever babble of hip-hop at the light on 89th. His students pretend they belong to that angry world. He attempts to instruct them in the false freedom, drugs and money, the commercial depths of the music business. Given the choice, they would rather listen to him on the slaughter at Antietam or the Thru Hikers who make it to Maine. The light changes, dead silence. The city can’t get its breath. He lights the vigils. Then the thud of the metal fire door shoved open, and Murphy comes toward his little altar of skill and deception. Paul Flynn takes the first game with a crafty rook ending.

Joe twists the top off a beer. “What harm?”

“None at all, a hot night.”

“Otto Sauer”—Joe gulps from the bottle—“he was a neighbor made his own in the cellar. That was back in the town my parents came from. Prohibition. My father said it was the best, better than Guinness in the field hospital before they shipped him home from the war. But he drank Bud when I was a boy. It was cheap. He was barely making it till the next war came round. Did I say he sold insurance?”

“Murph, you never said a thing. Except you came clean about Salvador.”

“Not so clean, but I was raised with these stories, just a few of them packed when they left Ansonia, Connecticut. The beer and the watch, the heavy one I carry, made by my grandfather on the kitchen table, and the teapot from Ireland. Did I show you the teapot I brought with me from home?”

“You did not.” Paul Flynn is laying out the rank and file of their men. His friend has never spoken of his family beyond a mother and sister who dote, which was to be expected. There is something near sacred about this night, with the heat pressing down, and their lofty position in the playground with the sticky rubber surface so the children will come to no harm, the pilfered candles flickering. A beer-drinking vigil. “No teapot,” Flynn says.

“Well, every family has one—a pot, a plate, a spoon—the memory totem with a story that tells you where you come from, though not one of us ever got back to Ireland.” He puts the beer aside, not the solution. “Though many families do not have the revered item, nothing to show if the shanty is torched and the men mostly missing. But I have this goddamn teapot.”

Back in his room, Paul Flynn stands at the open window watching Con Ed work a pit, the men stripped to the waist. Wearing their safety helmets, they carry their lamps with them to the underworld. A connection has frayed or blown right at the doorstep of the school. On this extraordinary night, he has witnessed something like a confession. So out of practice with the sacraments, he did not say go in peace at the end of Joe’s story, or drama, that was it—a drama to break your heart, like a movie that brings you to tears and you’re ashamed when you go out into the night. The shame that he bears at open emotion, as a man of his time, as a priest. Lying in his room with the power outage weighing on the city, he figures they are of an age, an age that kept the family secrets, Murph’s self-effacement presumed to be the mark of a humble man, almost holy. And all the while he was part of this extraordinary family with a movie actress mother, his sister gone to the bad, the heroic father. Insurance, the man sold insurance against the demons—a bent fender, disability, death. Tim Murphy seemed like the father in a family movie pitched high. He suggested as much—Dana Andrews, Jimmy Stewart?

“You’ve got the wrong war,” Joe said. “You’re the historian.”

True, but the Murphys’ epic skimmed time, like the links his students get on the Net, doughboy to U-boats to militant Jesuits, Mack Sennett’s Bathing Beauties to the tearjerkers of post-World War II, Melville to Manny, a Portuguese fisherman after all. He’s a throwback, warning his kids the links are too easy, back to the books, the whole story. Upon the roof they had played lightning chess, swift careless moves played so badly Flynn folded the board. The night was thick, noiseless. Joe walked to the roof’s edge as though he needed a breather before going on with The Murphys of Land’s End, the last bit: how he botched his mother’s wake, laughed and sang as if to please her, in his eulogy had carried on about day trips to keep her truant spirit alive. Flynn wanted to say, Why did you come back? But said, “Take more time.”

“That’s what they all say. I’ve had my time. More than allotted for the yearly visit.”

They were standing at the door of Murphy’s room, that bare cell he chose to live in. In the flicker of a vigil light, he held the teapot up for view, cream china with little shamrocks. “Our mother feedeth thus our little life, / That we in turn may feed her with our death. A fragment, not one of my poets.” But he’s never told Flynn about his poets of contemplation. His pal with the chess set in hand now had the burden of his incomplete story. He had left out Fiona.

At dawn the air conditioning kicks in, a blast of cold air stirs the papers on Joe’s desk. His copy of the notarized agreement with the flourish of Damien Forché’s signature, letters with Loyola’s crest in the hopes that you will take counsel. . . . The psychiatrist on 96th Street to be considered, and a note in Gemma’s bold hand. They had been laughing at excursions, the fancy word Bel used. When a boy, he had looked it up in the big dictionary at school. Escape from confinement; progression beyond fixed limits. And the treats—twenty-eight flavors, fried clams and franks. They had been laughing at Bel declaiming Moby. Gemma handing him her scribbled note: Pick up Ball Park Mustard.

“Yes, home in time for supper.”

Dead letters, still, he must deal with a note from the young attorney who patiently explains once again what constitutes a crisis under the Witness Protection Program. Terminal illness permits the bedside farewell, or death by natural or unnatural cause. Joe Murphy’s heart flutters with something like joy at the prospect that he must give his life to spring Rita. Then considers the chance it may work the other way round. Place your bets: the route is not perfectly clear, not inked on a map of Rhode Island.

BON SOIR

“I opened with nighties, lingerie. When I went into casuals, I’m thinking, Night and Day, but by then I had what you call a following.”

Mimi Salgado talking to Preacher—holy, you can see by his eyes, dark orbs of wisdom. Lean as a saint who prays in the desert, though pale as an angel of the Lord. The miracle moment. Mimi is early, alone in the Tabernacle with Pooch at her side, and Preacher is just there in a white Nehru jacket, just there, placing Bibles on each chair. She is stunned by his humility. How many pilgrims would gladly assist.

“Soir is fitting.” His voice has that blessed conviction, just gabbing with Mimi. “Night is good. When the day’s work is done, night is the Lord’s blessing.”

Mimi now distributes the Bibles while this Messenger of the Gospels lights the candles for prayer. Helpers in blue robes come to test the mike, set up the system. She can’t believe she has mentioned nighties to this chosen man who fasts, cleanses his body for Jesus. Pooch trails Mimi chair to chair, nipping at her heels, just as helpful. Sweet thing must stay in her bag with Bow Wow Biscuits when prayer and study begin. Only now does Mimi notice the ribbon marking the page in each Bible. Matthew 6, though how was she to tell which verse, her eye running down the page settles at 6:19—Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal. Perhaps that is this day’s text, and if not it is a sign. She has missed the last meeting, fighting with her landlord who won’t ante up for hurricane insurance. Costs a pile! So? It’s his mini-mall, right in the swank heart of Boca. Her father could handle that bastard, one visit from Manny Salgado would cook that slime’s meat. She fears water damage, moth in this season devouring cashmere, shoplifters, spiraling winds, the vacant eye of the storm. There are four named hurricanes swirling in the Caribbean. Settling Pooch in her bag as the flock straggles in, Mimi repents: she would never seek the aid of her father.

Preacher, wand of the mike in hand, marches the length of the stage, flips the page: Matthew 7:6—Do not give dogs what is holy; and do not throw your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under foot and turn to attack you. Now, that is a lesson hard to figure. Pooch has occasionally nibbled at her toes. Bow Wows are little treats, not manna from heaven. She prays for understanding. Jesus meant beasts, not Yorkies. Preacher now raising the mike to heaven, His grace to descend.

“Someone give me a hallelujah.” In a mighty chorus, men and women, old and young, cry out the response. Preacher urging his flock to recall how generous they have been to a son or daughter, to a neighbor or husband. “Pearls before swine. And were you not trampled. Did they not turn to attack you. . . .”

One side of Mimi, a woman’s face is washed in tears; the other, a boy trembles, his whole frail body shaking with the truth of the Messenger’s words. She sees Rita Murphy by the side of her mother’s bed, Carlotta smiling sweetly, asking her daughter to bring the nurse, calling the intruder nurse, a cup of tea as the heavy woman lit into the ruined flesh that fell away from her mother’s bones.

“Maybe tea’s not her thing,” Manny said. He did not even know the pounder’s name.

When Mimi returned, the woman had flipped the patient on her side, so her mother could not see her daughter rejected with the porcelain cup and saucer, sugar and cream.

“I like coffee, I like tea. I like the boys and the boys like me.”

Her father turning from the window, where he watched for the thugs, laughed for the first time in months. “Maybe coffee?”

“Coffee, you guessed it.”

Which began their mornings of feeble jokes and the stout woman’s muffins, coffee cake, feasting while Carlotta wasted.

If she had known then that sickness was not of God. There is only one Great Physician, Jesus. If she were granted another moment with Pastor calling for a Moral Crusade—“Give God a hand!”—she would tell how she came to Boca, trampled by her father, then by her husband, who lived with a whore in her Tudor, paid off to get out of the way like she was still standing there with the tea set. How Tony Brett, that bullshit name, her brother said get out, get out long before the investigation. If another miracle moment was granted with Preacher, Mimi would tell how she built the business, how at Bon Soir she discovered her gift, advising concealment or exposure, seeing each body in her boutique with its soul.

That night the tides rise with Hurricane Edith. Pooch whimpers as Mimi tapes the plate glass windows of Bon Soir. The lights flicker, go out. In the dark she touches the fine linens and silks on their hangers, lace nighties, cashmere sweaters and shawls in their Frenchified cupboards, every garment so fragile, defenseless. She sits on the Yorkie’s little chaise longue. If the shop goes with its goods and her precious girl, Dear Jesus, let them go together. By candlelight she reads in Matthew: houses built on stone which withstand the storm, or houses built on sand, and the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell; and great was that fall.

Edith falters, blows up the coast. The storm is played out by the time it hits Rhode Island, flapping the awnings in town, watering Gemma Riccardi’s basil and tomatoes, wetting the fresh concrete in the lap pool that runs at a stylish angle in the sandy earth at the end of the Murphys’ lane.