VI

Shadowbrook

’Tis an inevitable chance—All must die.

—Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

How glad you’ll be that I waked you. —James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

He is on the defensive, black king cut off in the back rank. White threatens mate, at which point the Murph loses concentration. Flynn taps the board, calls him to attention. His opponent has wandered. It’s been this way since they drove up in the van meant to transport soccer, football, debating teams—their kids at Loyola. They are in the vicinity of their old haunt in the Berkshires, seminary days. They share a room in a frilled and quilted B&B, Flynn’s chessboard on a lace tablecloth.

Paul takes the game. “Sorry about that.”

Joe’s the one who should be sorry, drifting away. They have one day left of this jaunt before heading back to orientation spiels and opening classes. But, then, Father Murphy has already been away, alarming those who love him, his sister and Flynn fearing the old ticker giving out, his body awaiting identification at Bellevue. He left all certification of himself in the top drawer of his dresser, under the broken pieces of a teapot he meant to have mended, imagining Rita’s cry of disbelief if the shards were discovered, the fate of their mother’s teapot compounding the tragedy of his death. Or disappearance. One blistering morning, having recalled his matins with precision as though he said them each day, he takes the bus on Lexington Avenue. Just boards a bus, what’s the crime? To be truthful, that’s where he’s at in the examination of conscience. To be truthful, he was in control, stealing away.

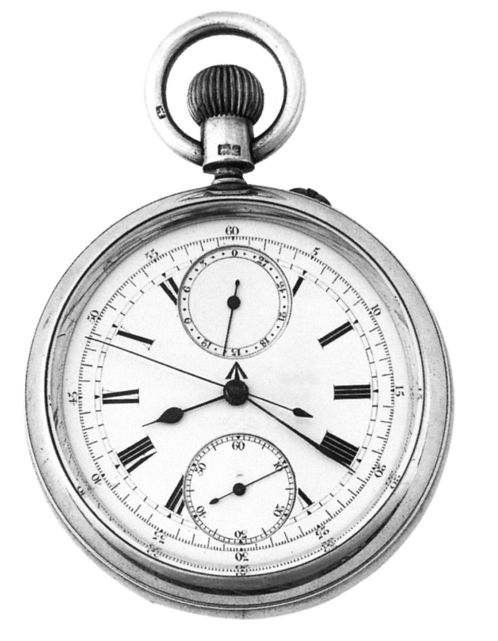

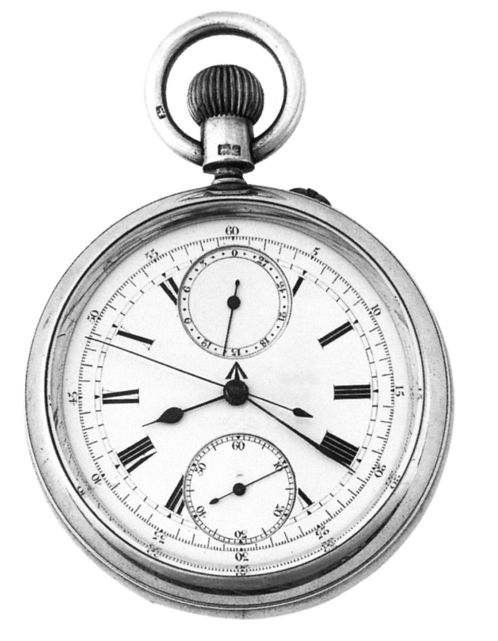

Not away: back, retracing his steps to the old schoolhouse downtown. The scarred oak door no longer bears the artistic sign with a rippling banner proclaiming Anima Mundi, the door open in the insecure city with guards at every turn, even at Loyola. The entrance hall much the same, in that urban poverty, when blessed, has a sameness in cement floors scrubbed, ammonia masking cabbage, in a dead quiet not to intrude on the city’s hum of prosperity and well-being. Wandering the large schoolrooms, he recalls how cramped the shacks in Aguileres, their airless hush, chipped plates and battered implements. Very early, though his grandfather’s watch is no longer accurate, he sits on the back steps leading to the rooms above where the inmates sleep. Inmates, joke of a word from back then. No one to listen, elegy of a sort, scars of love and war.

A clatter in the kitchen, morning smell of coffee. He remembers the back stairs with the broken fireboxes, the way to sneak behind the scenes, scenes of children tended to by the collection of mothers and fathers. Scenes of feeding the hungry, clothing the naked come in from the Bowery and Tompkins Square, of a collection of souls seated at long refectory tables, some residents, some travelers with their bedding and bundles. The back way to sneak upstairs, but he sits on the steps and they pass him by, the new people, some like social workers with clipboards and cell phones, one young woman in a sari, fair and plump, could be from back then. Her boy with knapsack wears a Catholic-school uniform. Oatmeal, the glutinous mess dealt out to welcome the day, a memory whiff from the few mornings he did not make it up to Fordham to teach his classes.

“What the hell, Murph!” What the hell was he up to, going off without his meds. He looked a wreck upon his return, dumb-struck in the doorway of Flynn’s room. When Flynn finished dressing him down: “Call your sister.”

His sister has surfaced out of the murky protection of her marriage. At the end of a preposterous story, Flynn said, “The worst you can say, she set the dog up for the kill. You know it’s the sort of thing they go for.”

They were the television people with time to fill. Eager for any curiosity, they had blown Rita’s cover. Then she was free to call, but Joe, Joey, had taken himself down to the old Mundi in the seersucker suit gone ragged at the cuffs, worn thin in the butt. A foolish game of hide-and-seek, rook to king’s closing, hiding out on the back steps leading up to the iron cots of poverty, while his sister choked back her sobs. Sampling the preferential options for the poor, while Rita and Flynn feared for his life.

Flynn dialed the number, handed him the phone.

“This about the dog?” Rita’s husband with the raspy voice of a crook, that’s unfair, the phlegm of a man jolted from deep sleep.

“Joe Murphy.”

“Sweetheart, it’s the holy father.”

Rita’s weepy refrain, “Joey, where have you been?”

He’s on the defensive. “Downtown, Rita, good works.”

Listening to dog stories, to the confusion of a lost daughter found, not his sister. Oddly enough, they don’t speak of their mother.

Where has he been? Another goose chase: fear of impending death, a case of angor animi. How he does talk since he went off to the seminary. After many phone calls Thanksgiving is agreed on. Rita will come to New York. He learns that Rita is stretching and bending, connecting to the temple of her body.

“I get down on the mat, Joe, when my husband,” a whisper here, “when Manny plays golf.”

Two old priests in the Berkshire Hills with a purpose. Flynn’s to accomplish another stretch of the Trail he’s been piecing together for years, a dotted line slashing the Appalachians, his secular pilgrimage. Murph has suggested the climb to Assisi, a trek to holy sites in Ireland. Isn’t Flynn Beantown Irish? All rejected for the final destination not yet accomplished, a mountain peak in Maine climbed in a state of Protestant ecstasy by Thoreau, who never made it to the top, got lost in the clouds. In Flynn’s book, the wilderness holds off the fumes of life, clears the head for loss of self. Joe Murphy, ordering a cappuccino in a tourist café, thinks Paul’s quest is the flip side of his sister’s healing self-discovery of muscles and joints. Could be the same fix, who knows? Not Murphy, S.J., who fears life slipping away. Well, he did not find the cure at Mundi, waiting for the day to begin with the glob of oatmeal in his bowl, or for the flesh-and-blood apparition of the girl beside him in bed, or in some patient traveler listening to him come clean about back then. How kind they were to take him in, suspecting he was not a flophouse bum, letting him work on their newspaper, which was much the same, caritas, pacifist manifestos, blasting the present war taking place in the desert. Time not moving on for the poor: this was the miracle then, that it all worked, even the black and white television in the community room with the old rabbit ears, the evening count of missing and dead. They took him in for ten days without question, as they had the let’s-pretend-poor girl—Fiona O’Connor. Joe Murphy—let him write the short, encouraging bits.

“Were you a teacher?”

“I was.” Not revealing high school math at Loyola.

“Nice piece.” A short take on Ignatius giving up his dagger and sword at Montserrat.

Not telling he’d written no more than pleasing letters home and graduate-student papers so long ago, studies celebrating the poets of contemplation, their lines now scattered in his head. Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back. He had asked too much of language. She put a finger to his lips. And there at this old Mundi, so out of this world, he was silenced again. No one to listen, busy with their worthy pursuits, in any case no survivor to look back to the first day he came to this schoolhouse in civvies. No authority sent him, all on his own, for some grail beyond belief in sonnets or the course set by Isabel Maher in a shingled house in Rhode Island, her boy would wear a black soutane. Back then, he had taken the Broadway Local downtown for clarity of conviction, found more than he bargained for. Rebellion of a sort, followed by the reward of Aguileres. The knowing eyes of the campesinos before the display of his gringo fear as he traded blessings with their women. Salvador was the hard place to go, too far, a world away from the girl’s gift of a saffron T-shirt, from the purity of comforting manifestos. About love he was always certain. He’d simply gone missing, as always taking the easy path. Sure it’s your choice? This time the Lexington line returns Murph, Padre, Prêtre uptown to his post. A blistering Summer day. Teetering on the curb, he waits for the light to change, makes it across Park Avenue to the far shore of Loyola.

Now Joe Murphy has this day with the shops in Lenox, little connection to their wares—silver jewelry, pottery, scarves of earthy colors, ski gear for the winter season. Glossy covers in the book-shop window promoting food, gardens, politics and the many paths to renewal hold no interest. He enters a store with expensive games and toys, buys a wooden chessboard for Flynn, the meticulous work of a craftsman inlaid with dark maple and pale ash, a purchase not in his plan for the day. He’s free till the hour when he must pick up the hiker, top of Mount Greylock. In the van he heads out of town to find Shadowbrook, a rich man’s extravagant cottage, where, as putty in his professor’s hands, he was instructed in theology. When the order bought the mansion to house seminarians and their teachers, they did not change the name. It burnt to the ground in the Sixties, was rebuilt in industrial brick, the era of Jesuit grandiosity over. Loyola’s followers dwindling, it was sold to a fraudulent guru. That act cleaned up, Shadowbrook is an upscale center for yoga, many in the community celibate. An amusing history to Murph, not to Flynn, who is after the transcendental experience, attempting this day an easy climb to the pinnacle of Mount Greylock. Flynn wants the panoramic view from the heights, the Civil War Monument lording it over the Housatonic River, not the backward view of personal history.

Women on the lawn of Shadowbrook sway and extend. Their bodies, hefty and slim, follow the supple movements of their leader. The priest waits by the van, looking out over the sloping expanse of green that leads to the tall pines and larches he remembers. Can that be? The same trees, chosen by a famous landscape artist whose name he once knew, arrested in their growth? And the glistening Lake Macinac, which he compared unfavorably to the bay in Rhode Island, every day finding it untroubled and dinky as he looked out from his cell in the mansion with marble floors, with ceilings embossed in white plaster, with a chapel where St. Ignatius, done up in mosaic, held aloft a golden cross. When the women end their session, their class—what to call it?—and trail into the puritanical pleasures of Kripalu, that is the true name of this spa, he discovers the path he once walked in contemplation, sees the spot where he made a pass at Loyola’s exercises but never saw Christ conjuring wine at the wedding feast, multiplying loaves and fishes. Light plays through the dark cast by the branches above. He sits on a bench, heart having its protest at a small incline as it had at old Mundi when he climbed the back stairs.

If he were to walk down to the lake, then hike back up to the van, he might bring on his death, choose both time and place. He’s been thinking about that, about a poet, one of his, who wrote a treatise claiming suicide not a sin, though noting the hands of a suicide are often cut off, buried separate from the body. Those severed hands may have been scare tactic, only a story—still?

He figures what Flynn will say, “It’s against your religion, Joe. Play golf.”

“Ride the little cart to redemption?”

The shadows of the trees stretch across the lawn, reaching toward September. An old maple early consumed in flames . . . Summer ends now, now barbarous in beauty. Shuffling, unsteady on his way back to the van. Hawthorne named this place while writing his first Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys: its play of light and shade enough this day to keep an old man among the living. Before driving on to the next lap of his planned excursion, sitting up high in the van, Joe Murphy closes his eyes against memorializing the view of his spiritual failure. Awkward with the key in the ignition, he feels the shade of his father’s good hand, its swift moves with a clutch. The dead arm, swung with grace into position, holds the wheel steady, and they’re off down the lane in the black Ford, property of Prudential. A supernatural event witnessed every day as a boy.

At Melville’s house, he waits for the tour with a couple from Brooklyn. This day only the three of them will pass through the house where the great book was written. The wife, worn notebook in hand, asks if he is a Pequod Person.

“It’s a Web site,” the husband says, clearly proud. “They know it all, the binnacles, halyards.”

“It’s that you look like a scholar.” The wife is girlish, excited as she grazes the gift shop items, whales on coffee mugs, T-shirts; prints of blubber being hauled on deck. “We’ve got that one.” The one with the great splashing tail, little men cast into the consuming sea.

The husband is entertained by his wife’s obsession, by her notebook packed with Melvillian knowledge. Joe thinks how very nice, the mild man in love with her love of a book. He tells Joe of the six thousand fans logged on as Pequod Persons, his wife a second mate, like Stubb. “She knows it all, the rigging, the mess, what Herman ate for breakfast.” This is their third visit to Arrowhead, Melville’s farm. They have been to the Seamen’s Bethel, New Bedford, maybe ten times.

“I know it,” Joe says. He pays up for the tour, buys a postcard to send to his sister.

And they’re off to the Chimney Room of the farmhouse, trailing a chattering docent who’s corrected at every dish, spoon, cradle, and daguerreotype by the second mate from Brooklyn. Here’s what Joe wishes, to be alone, a boy’s wish to be in his bed with a book, Ovid, the Gallic Wars, no—Moby. No teacher, no guide, just the neat story. He lingers behind in the parlor with the family portraits, the cupboard with fancy cups and saucers Bel might not have loved, never cherishing more than the Irish teapot. Loud and clear, the Pequod Person tells all, the year the writer, then famous, purchased this house, bossy mother-in-law moving in, social scene with well-to-do neighbors. In the Melvilles’ bedroom, she identifies the child’s cot as Malcolm’s, the son who would shoot himself to death.

“On East 26th Street, not the Berkshires.”

Finally, the upper room, the study with volumes (inauthentic, not the master’s according to the second mate) of Milton and Shakespeare, Sterne, Montaigne, Chaucer, the writer coming on bookish, the desk, pewter inkwell, pen, tiny glasses, facsimile manuscript pages of Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Joe lingers, lets the tour retreat to embroidery and scrimshaw downstairs, stays on for the great hump of Mount Greylock swelling into the bright ocean of sky, Melville’s view each day as he chased the thrashing enormity of his subject.

The book failed: Joe remembers from way back, the obligatory class in American Lit., duty for a doctorate never awarded. The writer failed, went mad for a bit, then lived out the time allotted. Joe sits in the forbidden chair where Melville put his bible together, chapter and verse, his eye on the Leviathan fractured into six-over-six colonial panes. The constriction in his chest familiar, almost a friend. What was that fancy word he tossed at his sister, meaning fear of impending death? He is calm, piecing together Mount Greylock with his mother reading a book never finished, wonderfully calm. Why always day trips? Why had they not come to this upper room, the site of creation? Why home in time for supper? Bel lay Moby aside, a doorstop in an ugly library cover, though one day in the Spring . . . never enough stories. Dissolves to the Buick, sitting up front with his mother, girls in the back, Rita and tag-along Gemma.

Hair escaping the green cap, just a tendril, as though plotted by wardrobe or makeup, a cap military yet rakish, home-front fashion for the duration. Coat slung over her shoulders, epaulettes, brass buttons. Three children seated before her. A show, a game? A beam of light shines upon her through a dusty window. A dark, cold chapel. The girl with the chipmunk cheeks looks down at her magazine. Close-up of a housewife cutting an apple pie. Pages flip to chocolate pudding, 6¢ a serving: enjoy the Niblets, save the can; to a sweet woman embracing a soldier, From This Day Forward, a complete novel in this issue. The girl coughs, coughs again in this damp place, as though to forestall what’s coming, her mother pressing open the book, reading to herself, then out loud.Too loud.

On one side of the chubby girl, who wears a navy Spring coat with velvet collar, childish hat with turn-up brim, the boy in long pants, older, takes baseball cards out of his pocket, eyes cast down on words he knows by heart. 1941,Ted Williams bats 400 until the last game.Takes the risk, goes six for nine. The boy looks up at the reader, then shuffles the cards till he comes up with the Yankee Clipper, fifty-six slams in a streak, reading stats, not flipping his cards for the picture.

The woman reading whips off the green hat, unclear if it shades her eyes or the page in her book, throws it toward the children, then shrugs off her coat. Now her voice rises, you must listen to this.You must listen. Alone in this performance, not a game. Her words, the words from the book, bounce about the empty chapel where men prayed before sailing off on the ships. Cut back to that scene in the Buick, attention of the children on the road, all three listening to her go on—whalers and fishermen, the sea with its dangers.

“Ask your father. Get him going on Lloyd’s of London, marine insurance.”

The billboards and towns flashing by. Lowlands by a river.

In the chapel, all three restless in the hard wooden pew, half listening to the writer’s reflection on the dead; squirming kids, the boy turning to the girl in a coat too small, her big hands caressing a box camera, then cupping the lens. She smiles at the boy, the sly what-are-we-into grimace of adolescent superiority.The dead, Bel reads on, nose in the book, then chin tilted toward her audience, which might as well be the cranky apparatus of silent movies.There is something terrible in her stumbling over an urgent sentence, then hitting her pace.

“Yes, the dead, that they tell no tales, though containing more secrets . . . Why the Life Insurance Companies pay forfeitures upon immortals.” Skipping about, having lost her place on the page in the half-light of the chapel, beginning again, “Methinks that in looking at things spiritual, we are too much like oysters.” Then, slamming the book closed, giving it up. Out in the sun, leaning against the fender for a photo, waving at the children, hers and the intense girl with the camera, waving, dusting it off, a bad show.

Stubb, husband and guide block the view already blocked in Joe’s reverie, alarmed that he is sitting in the master’s chair, though kind to the faltering, the old. Sorry, Joe Murphy is ever so sorry, lost in admiration for the sacred room, though he doesn’t think he has the necessary devotion to become a Pequod Person.

Flynn is waiting at Greylock, happy and hungry, piece by piece achieving his earthly goal. If not the world at his blistered feet, at least the Housatonic Valley. After prime ribs and a bottle of Merlot, they repair to the B&B, set up the craftsman’s chessboard. We do not have to ask who wins or why they turn from each other to pray or not pray, each man to his quilted bed. Father Murphy sits upright in too much softness, too many pillows, breath coming heavy and slow. A porch light from below is switched off, giving the stars their chance. What had she wanted them to learn, a lesson to each excursion? The lesson that day in New Bedford, sixty years ago? Displaying the frail show of her immortality, she had failed to entertain them, closed the book. Failed, like Melville. The last day trip, Bel’s final performance. And on, she went on, Isabel Maher outliving, as we all must, our myth.

Never enough stories. That semester, while Father Joe dwells on his death, he is given, depending how you look at it, a chore or reward. He is given Annie Pappas, a skin and bones girl with a strong mind. Preparing for SATs, she’s far ahead of the pack, an irritant to her fellow students slogging through practice tests.

“I’ve got the math gene,” she says upon their first meeting. “Can’t help it.”

“I won’t ask you to help it, but I doubt I can help you. I only know what’s in the books, the problems they explain.”

“That’s OK,” Annie says, taking charge. “I’ll just come and we’ll talk, get me out of their way. I mean, I could sit at the back of the class and doodle.”

“Come along. I’ve time on my hands.” He thinks, a Greek nymph or naiad, she’d be pretty with flesh on those delicate bones, but maybe doesn’t want to be pretty. They sit in his empty classroom with problems before them, problems she can solve, show him the theorem, display the proof. When Annie gets into fuzzy nominals, he knows she’s overreaching. Finished with her instruction, they talk. How her father wants pre-med or business, even teaching, God help us, not risk her life tripping to Mars, as though that’s where her smarts are heading.

“It’s not the unfemme thing, math and girls. Nick Pappas was poor, really. Cut high school, bagged groceries. So—how to live?” Speaking of her father’s grit and good fortune, Annie mimes nausea, quotes the Times. “The café luxe . . . flawless cuisine. Not to mention Papa’s em-por-ium with globs of fab food.” Apparently she will not be nourished by this abundance. On Fridays a car picks her up, drives her out to the Pappas farm in Connecticut, where she has horses, a mare and her filly.

“Your friends?” Father Joe has given up on algorithms and negative numbers.

“Draw a blank.”

He thinks that his role must be pastoral, that the head of the department, a stiff young man given to regulations, has thrown Annie his way, unable to deal with her solitary ways, her extraordinary talent, then thinks, naturally, of his failure with Elizabeth Strumm, the model still starved for attention, Pet, this very week celeb, staring him down in the stationery store, cover of Elle. Annie wants no one, but comes to their sessions, knowing it’s a joke.

Or not a joke. At their third meeting she gets him talking, Father José in Salvador, a country where I spent some time, dealing out beans to his pupils, fashioning an abacus of sticks and twigs, how he should have taught Spanish or English, how he once had a gift for math that backfired, so to speak, a twist of fate his job in this classroom, how he has finally mastered Calculus for Dummies, this said to get Annie’s smile. What she wants, to be left alone with her head for numbers, lead her life. Annie wants early admission at Yale. New Haven, she’ll be near her horses.

“My father,” he says, “went to Yale for a bit.” A fact of Tim Murphy’s life he’d forgotten.

“Didn’t finish?”

“There was a war.”

The next week the old priest brings Annie his grandfather’s watch, the watch Joe the Murph famously places on his desk during class, checking to see if it hits the hour same time as the schoolroom digital.

“I can’t.”

“Oh, you must, to please me.” There’s just time enough at the end of their hour to tell her the story of Patrick Maher, a man who fashioned every wheel and cog, who figured every half-second to the minute. “An old watch, old system, but you might enjoy it.”

Tears mist the girl’s eyes, not so tough after all, “Well, thanks.”

“Now, then,” says Father Murphy to lighten things up, “ever hear of the pancake problem?”

“Oh, that.” Laughing, sniffling. “The knife bisecting the pancakes, that’s dumb. It works with two, easy.”

“Not with three? I never got hold of that one.”

“You’re not supposed to. A classroom game, unprovable theorem.” And she’s on to factoring polynomials while the Murph fights sleep.

That night, he begs off the evening news and chess. Father Joe at his desk correcting papers. When he has finished his work, he registers each grade in his grade book, to be transferred to his computer file next day. No student has flunked, no student has triumphed. He has no fear of impending death, though he seldom returns to the doctor who prescribes his medications, letting chance take its way. Watching his heart on the screen, its blip and wayward flap of aorta, the doctor pronounced: Years of wear and tear. To Father Murphy, a poetic diagnosis. He lives with his affliction, as he has learned to live without the higher calling.

He stands at the window to watch rain brighten the sidewalks, torrential rain transforming the city street. A man walking his dog against the wind gusting from Central Park is soaked, puddle jumping in the circle of lamplight, drenched, though he looks to be laughing. What a set, Bel said, singin’ and dancin’ in the rain.What a movie! The magic always got her, though she knew the spectacular effects of the business. Lights, camera, action—nothing to bother us with, to set curious children dreaming, leaving us in shadowland. Some lesson there. On one of his visits home, they’d watched Gene Kelly swing round a lamppost. After Salvador surely, just the two of them sitting through the credits. The gutters on 88th Street are flooded. The storm theatrical, foreboding, but tonight he has no fear of dying. He plans, or prays, to slip away without notice, in the family tradition. Forgetful, he feels for his workman’s watch.

Rita begs to be left alone. Paul Flynn closes the door to Joe’s room. She watches the cars make their way round the school buses waiting for the students of Loyola. It has been the longest day, not yet over. The funeral Mass, the lunch, so much talk from Joe’s colleagues, all praise. A saint, one old fellow said, but Flynn laughed. She was glad of it, of her friend’s closeness to her brother, his perspective. Rita wears the blue suit bought for her trial. She did not think Joe would want black. He was so cross about the black veil she wore to Bel’s funeral. In a while she will call Manny. He’ll be waiting by the phone. You never met him, she’d said. I’ll go alone. Nina and Ash will look in. . . .

Manny not listening. Babe? Babe?

Perhaps she will have to pay for her slight, for wanting to be alone with her brother laid out in a black robe. Once Joe called her a cow, then took it back, but she never forgave him. She had gone moody and silent, not up for his kidding, some story he had been reading.

She sits on the bed, springs squealing under her weight. Can Joey have slept each night through this punishing music? His desk. His fat reading chair spilling its guts, books above in the closet. Paul has taken away the clothes. He has made a packet of photos and the remains of Joe’s life: a tin skeleton, pieces of teapot, cigar box with Lieutenant Murphy’s honorable discharge 1918, a letter from Bel begging forgiveness, a postcard of a rambling old house addressed to Rita Salgado, 63C La Cumbra Terrace, Tarzana. No stamp, no Zip Code, no message.

Rita sits on the bed with these things, all these things in her lap. Daddy’s Tontine, the prize goes to the last man standing. Fumbling, attempting through tears the printed words on the postcard, Rita’s voice in the silence, soft as if for a Chatterbox story, I have been building , as if testing words in a dank seamen’s chapel, testing—then strong and clear, reaching angels and clouds on the flaking ceiling of the Bijou—I have been building some shanties of houses (connected with the old one) and likewise some shanties of chapters & essays. I have been ploughing & sowing & raising & printing & praying.

—Herman Melville to Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1851

A bit of a stretch, dear girl. Take it down.

The sun, whose rays

Are all ablaze

With every-living glory,

Does not deny

His majesty—

Comfortable in this register. We do not play to an empty house.