How exactly do we define what makes a house a home? Four walls, some doors and maybe some windows, a roof over head—is that a home? Is a tent made of cured buffalo hide a home? What about a rented room with only a curtain separating your family from the other family sleeping only a few feet away—can we call that a home?

At some point in the 1800s, Americans of all kinds called each one of these living arrangements “home.” Americans were in transition in the 1800s. They were moving from one way of life to another, and as they changed, so did their houses and their ideas of home.

For one thing, the purpose of a house changed a lot between the years 1800 and 1900. In 1800, most houses were the center of production as well as family life. The purpose of a farmhouse or even a townhouse was to produce goods that sustained life. Farmhouses produced crops and other food products such as cheese and bread. In townhouses, families often lived above a store or a shop for a blacksmith, tanner, or cobbler, and they might produce in their living apartments shirts and socks, or jarred fruits and vegetables for the winter. Most activity in the house was focused primarily on supporting life. People made what they needed to survive in or near their homes.

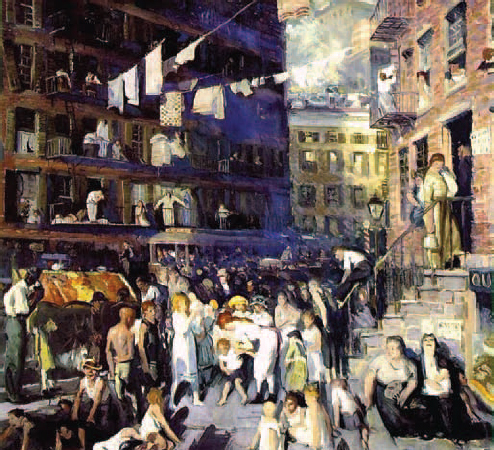

But through the course of the 1800s, this began to change. As the Industrial Revolution took hold in America, for the first time there were more jobs outside of the house than in it. Men and women alike took to the cities looking for a job, a way to make more money and improve their way of life. The financial or economic use of the house no longer existed. The house was now a place where goods and services were consumed, not created.

At the beginning of the 1800s, the home was the place where the production of food and clothing took place. This re-creation of a nineteenth-century home in the Appalachian Mountains shows a woman spinning yarn.

By the end of the 1800s, the home had become a place where goods were consumed, especially for the wealthy, and houses started filling up with THINGS.

The Household Players: Men, Women, Children, Servants

The role of men and women in the house changed a lot in those years. When the house was the center of production, women had been partners in providing life to the family. On the frontier, where life continued to be centered around the house and not around a workplace outside the house, women continued to be partners in production.

Although this partnership was by no means perfect or without flaws, it was generally accepted that a family needed both a man and a woman to provide for all the needs of the household. The “Little House” books, written by Mary Ingalls Wilder in the 1900s, were based on her real-life experiences with her family on the American frontier in the 1800s. They show us how important both “Ma” and “Pa” are to the household. Both are constantly at work—Pa doing his chores, Ma sewing, cooking, cleaning, washing, and all the while, educating her children.

During much of the nineteenth century, both men and women helped with farm work.

Ellen Bromley tells of growing up in Illinois in the mid-1800s, revealing a world where women worked hard, cooking, planting trees—and where women also got lonely.

We lived near Warner’s while we were farming. We were four miles from James Glenn’s. . . . Mother said the Glenns were so hospitable. Mother was very lonesome and homesick on the farm and Mrs. Glenn had her come over and stay a week with them just to make her contented. Mrs. Glenn doctored the neighbor women and was always helpful. She would keep her Bible in the kitchen and read it while making her biscuit. One time someone came along and asked, “Why are you planting apple trees when you never will live to eat from them?” She answered, “I reckon if I don’t some one else will.” I guess she did live to eat apples from those trees herself.

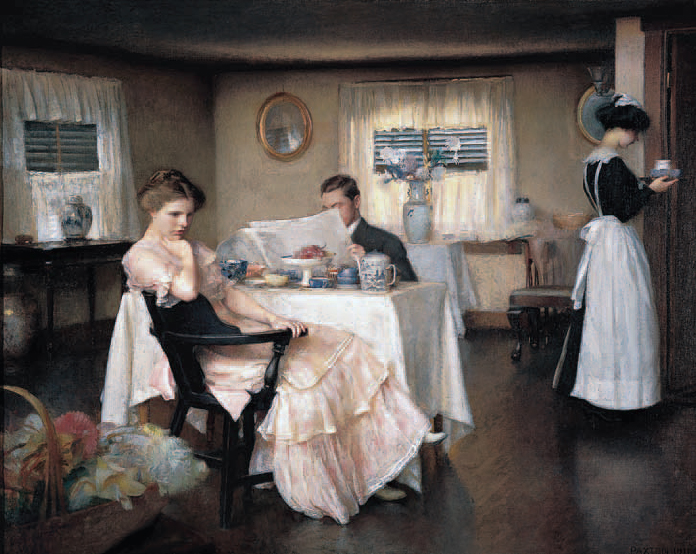

This painting shows a young family that has just moved into a new home during the nineteenth-century. It will be the wife’s job now to be a “homemaker,” while the husband’s job will be to earn the money she needs to make their home.

Things changed for women when men started leaving the house to work, and bringing home the goods a house needed. No longer were women partners in production. No longer was the house a place of production. The house was now a retreat, a center for leisure and comfort, a comfortable place to come home to after work was completed. Women became the keepers of this place and this idea. Increasingly, women were encouraged to make themselves and their houses a “protected” place, away from the dirt and grime of the industrial, working world. The house became a place to renew one’s spirit and one’s morals, to learn to appreciate culture and beauty; and the woman was responsible for carrying out this effect.

A whole genre of “advice literature” sprang up in women’s magazines in the late 1800s, coaching women on how to be perfect wives and mothers. An example from one advice book, called Hill’s Manual of Social and Business Forms, reads like this:

Whatever have been the cares of the day, greet your husband with a smile when he returns. Make your personal appearance just as beautiful as possible. Let him enter rooms so attractive and sunny that all the recollections of his home, when away from the same, shall attract him back.

Another advice magazine, called The Household, said it was the wife’s responsibility to provide her husband “a happy home . . . the single spot of rest which a man has upon this earth for the cultivation of his noblest sensibilities.”

How adults viewed children changed in the 1800s. At the beginning of the century, children were more likely to be seen as miniature adults. Farm families valued children for the work they could do, and big families were considered a blessing. Because they were expected to work alongside their parents, both in and outside the house, children were given more “adult” privileges in rural and working class families. This continued to be true throughout the 1800s in both rural and poor urban houses. Wherever children were expected to work, they were generally also expected to reach adulthood more quickly.

In upper-class homes in the late 1800s, children were expected to live their lives separated from the adults in their families. They spent their time in different parts of the house, supervised by servants.

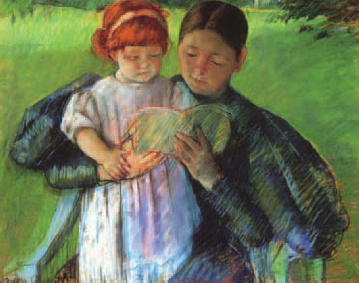

Mothers in the middle and upper classes of the later nineteenth century were responsible for teaching their children manners (such as the proper way to drink tea, as shown here) and morals.

In the late 1800s, however, things changed as the middle class grew in America. Servants in the home and advances in technology made housework unnecessary for middle-class children. Moral and cultural upbringing was almost entirely the responsibility of the mother.

In the more rural, pre-industrial society of the early 1800s, servants were often unpaid young relatives or neighbors of the wife or head woman in a household. They helped the woman of the house with her many tasks and in exchange they learned skills from her, skills such as weaving, spinning, cooking, and cleaning.

Then two things happened. First, the Industrial Revolution attracted many working-class women away from home and into factory positions. And second, the changing idea of home required that a woman take over the cultural and spiritual leadership of a household as her fulltime job—and hire Irish or black servants to do the other jobs of the house. What was once more of a “team” mentality of women working alongside one another became an employer-employee relationship. Servants of this second type were less likely to be seen as part of an “extended family.” Although they often slept in the house where they worked, they rarely ate at the same table with the family. They were hired to do specific tasks that the lady of the house didn’t want to do. They did not share the same work.

Servants who cared for young children allowed upper-class mothers time and energy to focus on morals, religion, and manners.

The nursemaids and nannies who took care of nineteenth-century children were often black women or Irish immigrants.

Hired servants in middle- and upper-class households in the later 1800s allowed “ladies” time to focus their energy on domesticity, piety, purity, and submissiveness (four traits of the “true woman” in the late nineteenth century).

Wealthy women in the 1800s were allowed lives of leisure because servants took care of daily household chores such as preparing and serving meals, housecleaning, and laundry.

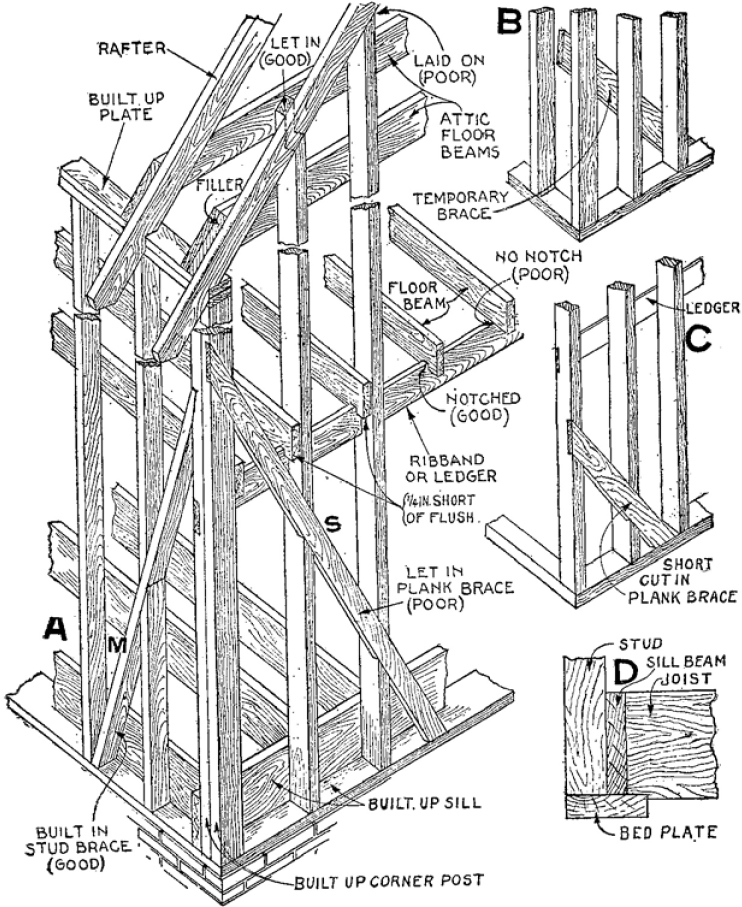

In the 1800s, European houses were generally made from brick or stone, as forests were less abundant there. But America had vast stretches of untouched forests and a thriving iron industry for making cheap iron nails. These two resources combined—iron nails and cheap wood—led to the construction of a new type of home in America called “the balloon frame.” The term was originally used in mockery, as many skeptics thought the new homes would blow away like a balloon at the first strong gust of wind.

Balloon frame homes were made from many strips of wood, much like the two-by-four boards of today. Also called “light frame” construction, the method looked like building a basket from wood, and then attaching coverings to the inside and outside. Instead of hiring expensive carpenters and masons to build their homes, many Americans hired a few friends, or they built their homes entirely on their own. The new method used lots of wood and lots of nails, but it didn’t take much professional knowledge, which meant it was cheap.

Balloon frames like this were cheap and easy to build.

And it was fast too: hundreds of homes sprung up in new communities, usually made from whatever wood was available in that region. The balloon frame was stronger than it looked. It held up, and its popularity grew, especially on the frontier where people had little money but lots of ambition. Today many homes in the Midwest (the frontier of the 1800s) still have homes built by balloon-frame construction.

At first, people thought balloon-frame houses would not last—but more than a hundred years later, houses like this one are still standing.

Every house was different. Southern plantation houses built at the beginning of the century were far more elaborate than the longhouses built by Native Americans in the Northeast. The longhouse was like a long tunnel in which many fires were kept and multiple families lived. Meanwhile, the slaves who lived on Southern plantations generally lived in one-room houses separate from their master’s home. The slaves’ houses were usually out of sight from the main house, and were like a small village with pigs or chickens roaming around and a small garden.

In the Northeast and South, middle-and lower-class families were likely to live in simple “foursquare” homes—four rooms around a single staircase that led upstairs to bedrooms and an attic above that. They usually had a cellar near the kitchen, where many foods were kept.

At the beginning of the 1800s, the houses of wealthy plantation owners in the South were large and luxurious. After the Civil War, however, many Southerners no longer had the wealth to maintain their huge homes.

Meanwhile, slaves lived in very different conditions in small houses behind the “big house.”

This nineteenth-century painting portrays the private lives of blacks, hidden behind the more luxurious white-people’s world. The white “mistress” is shown here peeking into the rich culture that lies behind her home.

In the Northeastern Native tribes, many families would make their homes within a longhouse like this, sleeping in the beds along the side of the walls and cooking their meals at a fire in the center. Although there was a hole in the roof, the air inside would be smoky from the fire.

Kimball, Nebraska Daily News

August 1887

We hear tell that sod houses can be comfortable. But the popularity of this little ditty being sung tells us another story!

Soon we landed in Nebraska where they had much land to spare,

But most ever since we’ve been here, we’ve been mad enough to swear,

First we built for us a sod house and we tried to raise some trees,

But the land was full of Coyotes and our sod house full of fleas.

The family shown here with their sod house would have had to put up with dirt and insects falling on their faces while they slept and muddy floors when the weather was rainy. The house would have kept cool in summer and warm during the winter, but the interior would have been cramped and musty.

Life was different for settlers moving West than it was for people living in the more established East during the same period. On the frontier, sod houses (or “soddies”), log cabins, and shanties were the three houses of choice for pioneers. Soddies were made from thick slabs of thickly-rooted prairie grass called sod. They were not ideal homes by any stretch of the imagination. Because they were essentially made of dirt, many bugs, rodents, and other pests dropped into the house. After a hard rain, water leaking through the roof could turn the dirt floor of a sod home into a muddy mess. Some pioneers added boards and metal sheets to their sod homes in an attempt to keep water out and present a more “civilized” appearance. But most of these homes were eventually abandoned.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT

A woman named Mattie Oblinger wrote to a friend about her experience living in a Nebraska sod house in the late 1800s:

At Home in our own house, and a sod at that! . . . We moved in to our house last Wednesday (Uriah’s birthday). I suppose you would like to see us in our sod house. It is not quite so convenient as a nice frame, but I would as soon live in it as the cabins I have lived in. And then we are at home which makes it more comfortable. I ripped our Wagon sheet in two [in order to] have it around two sides. . . . The only objection I have we have no floor yet. [It] will be better this fall.

The log cabin was by far the most popular on the frontier. It kept out wind and rain better than sod, and it lasted longer too. Log cabins were caked with mud, leaf, and twig mixtures to keep drafts from blowing through spaces in the logs, a process called “chinking.” Both log cabins and sod houses were equipped with a chimney pipe or gap in the roof to allow for a fireplace or stove. Log cabins often had stone fireplaces built into them, or sometimes a chimney made from sticks and mud.

The shanty was the result of the Homestead Act passed by the U.S. Congress in the late 1800s. The act encouraged Americans to settle the West quickly by promising free land. Like the log cabin and sod house, the shanty was a quick way to build a home and lay claim to a plot of land. The Homestead Act required settlers to “prove up”—meaning they had to prove they were living permanently on the land. This meant they had to have a house of a certain size built by the time the government inspector came around. Shanties were built directly into the ground, with a dirt floor and no foundation. They consisted of a few boards nailed together and stuck into the ground, usually covered with tar paper to keep out wind and water. The shanties were less comfortable than log cabins, but about as comfortable as sod houses, and more portable than both. If an inspector came to look at a large plot of land claimed by one family, the shanty could be quickly moved from spot to spot. Americans were creative when it came to claiming their new land!

A log cabin’s interior shows how simple these homes were. There was very little privacy for family members!