The term “Victorian” comes from an era in late 1800s England when Queen Victoria of Great Britain ruled over a period of relative peace and prosperity. During this period, the middle class grew in both England and America, where industrialization was changing the way people lived in and outside of the home.

The middle and upper classes who could afford to embrace “Victorian” ideals did so by introducing some changes to their houses. The Victorian house was designed to be a center of culture and refinement. Work was to be kept out of sight. Whenever possible, servants did the cooking, cleaning, and washing away from the family and their guests.

A scullery maid hard at work, out of sight of the family who lived in the home.

The scullery was the Victorian solution to keeping housework out of sight. Usually built near the back of the house, behind the kitchen, the scullery was where laundry and other cleaning was done. It was kept near the back of the house so that dirty water and other waste could be thrown out the back door. If a house could afford it, the scullery was outfitted with many of the laundry devices of the day. A copper bowl sat atop a fire for boiling linens. A “mangle” was used to push wet clothes through weighted wooden rollers to remove excess water.

A mangle, used for squeezing the water from laundered clothes.

A nineteenth-century “washing machine” and a trough for laying down the wet clothes.

The parlor was the one room that really represented the changes in a Victorian house. Usually situated somewhere near the front of the house, the parlor was used as a formal sitting room for entertaining guests. It was often closed during the week and opened only on weekends. The word parlor comes from the French word parler, which means “to speak,” but the parlor was used for much more than just talking. It usually contained a family’s best furniture, works of art, and other proud possessions.

The parlor would have a card table for games, a piano for entertaining guests, various paintings on the wall, and a fireplace for keeping everyone warm, usually with an ornate mantel around it and a mirror above it. Parlor pastimes included card games such as euchre, bridge, seven-up, and board games such as dominoes, checkers, and chess. Young ladies and their mothers might sit in the parlor to practice their needlework or to read a novel. In the late 1800s, thousands of pianos were sold to middle-and upper-class families, and they usually found their place in the parlor. Men, women, children, and guests would gather around a piano to sing or listen to one of the family members perform (usually a daughter). Also, photography was becoming very popular in America at this time, and the parlor was often just the place for a family photograph.

Today, the parlor has become what we know as the living room. Couches or sofas replaced fancy chairs, and televisions replaced pianos, artwork, and card-tables.

The women of the family enjoyed “genteel” pastimes in the parlor.

Most middle-class homes had very few bedrooms: one for the wife and husband, and another one for all the children. It was common to put two beds in a child’s room, and to have more than one child sleep in a bed. Beds in lower-class homes were usually made of wood, but the upper classes preferred metal, brass, and iron, since these materials were less likely to provide hiding places for insects. Mattresses were made of feathers, if possible. Although feather bedding was expensive, a good night’s sleep was highly valued, and many Americans considered the bed a symbol of a family’s future happiness.

A typical children’s bedroom in the 1800s.

In general, the bedroom was a dreary room. It was considered the most private place in a house. No one but family members entered, and so it was rarely decorated or well-lit. Usually, a jug and bowl were placed in the room for people to wash their hands and faces before bed. Wardrobes were used instead of closets, which didn’t exist at the time.

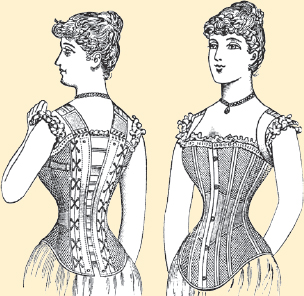

No one in the 1800s needed a closet, since most middle-class Americans at that time had no more than three outfits! Because laundry was such a chore, clothes were rarely washed and usually made of tough materials in dull colors that hid dirt. Underwear included corsets and underskirts called petticoats for women, and woolen long-john underwear for men. Corsets were tightly laced tops that pinched the waist and pushed up the breasts. They were usually painful and sometimes even a health risk, as they could make breathing difficult. Beauty standards for women in that time made most clothing uncomfortable. Men of privilege had less to worry about—their standard of dress was a three-piece suit.

EXTRA! EXTRA!

Ferris Good Sense Corset Waist

Faultless form, delightful comfort, perfect health and grace—every breath a free one, every move an easy one—the invariable result of living in the Ferris Good Sense Corset Waist. The favorite of all women who wish to dress and feel well. Made in styles to suit every figure—long or short waist, high or low bust.

Affordable for every family, children’s corset waists cost from 25 cents to 50 cents, misses’ from 50 cents to 1 dollar, and ladies’ from one dollar to two dollars. For sale by all retailers in the New York Area.

In the 1800s, just to have a bathroom in one’s house was a privilege. Bathrooms were for taking baths, not for using the toilet, which wouldn’t arrive until indoor plumbing in the next century. Hygiene was difficult for Americans, who didn’t fully understand the health benefits, and didn’t have access to indoor plumbing. Even so, many wealthy families began to recognize the benefits of a daily bath.

All bathtubs were free standing, not built into walls as they are today. Tubs had to be filled with hot water heated on the stove and carried upstairs. Since heating the huge quantities of water required to fill a tub took a long time, the same water was used for every member of the family. By the fourth or fifth bath, it was usually cold and filthy. Soap was made of animal fat and vegetable oils. Some truly strange things were used as shampoos, including cow fat and perfume or eggs and lemons.

As gross as it may seem today, a bath in cold water with vegetable oil for soap was better than nothing. Those who couldn’t afford a tub bathed even more infrequently. They smelled bad and were more likely to get sick. As the English novelist Somerset Maugham wrote, the morning bath “divides the classes more effectively than birth, wealth or education.”

Bathrooms had other purposes besides bathing. For one, medicine cabinets became popular in the 1800s and were often kept in bathrooms. Medicine cabinets contained many drugs, including narcotics that are illegal by today’s standards, such as cocaine, opium, and heroin. Medical knowledge was still limited and the addictive quality of these drugs wasn’t fully understood. Americans used powerful powders and elixirs to numb pain while the body attempted to heal itself.

Pear’s was one of the first commercially made soaps in the United States.

If you were a woman who worried that you weren’t fashionably plump, you might have kept this in your medicine cabinet!

The toilet as we know it today didn’t exist in the 1800s. In fact, doing one’s business inside the house was still a relatively new idea! For centuries, the outhouse remained the only option for Americans. An outhouse was basically a wooden structure built atop a hole in the ground. Despite many attempts to make them more comfortable—different-sized holes for adults and children, padded seats—at the end of the day, the design remained the same. One can imagine the discomforts. Outhouses were cold, and often built far from the house to keep unwanted smells away.

An outhouse was a small building set back from the main house. Going out to do “your duty” could be a cold, lonely business.

Corn cobs were often used instead of toilet paper during the 1800s.

The 1800s was a time of experimentation with new ideas for indoor toilets. The wealthy had access to some of the earlier experiments, such as the “earth closet.” The earth closet would look to us like a small set of cabinets with a hole built into the top. It was built without access to indoor plumbing, with the idea that the person using it would heap a small shovel-full of dirt onto the waste.

Almost every Victorian home of the late 1800s had a “chamber pot” in each bedroom. The chamber pot was usually stored beneath the bed, and removed and emptied by servants. The chamber pot existed since the Middle Ages, and it remained in use even with the invention of other indoor toilets. For Americans in the late 1800s, the chamber pot was an easy means of relieving oneself before bed, during the night, or first thing in morning.

The indoor water toilet had many names that persist today—the “water closet,” the “privy,” and others. The idea of flushing one’s waste away with water was actually an old one, but it wasn’t until the Victorian era that it became widely available. Both English and American inventors raced to invent the most efficient, pleasant toilet possible. By the late 1800s, people began to understand how disease was linked to waste. The old system of simply tossing chamber pots out open windows and into backyards was coming to an end. City planners wanted to develop a centralized sewer system that would allow city-dwellers to get rid of waste in a sanitary way.

A version of the “earth closet” developed in the 1880s.

On a cold winter night, a chamber pot like this was a good alternative to making a trip to the outhouse. In the morning, it would be emptied and cleaned for the following night.

The following is from a poem written as an ode to the outhouse, called “The Passing of the Outhouse” by James Whitcomb Riley:

When summer bloom began to fade

And winter to carouse,

We banked the little building

With a heap of hemlock boughs.

But when the crust was on the snow

And the sullen skies were gray,

In sooth the building was no place

Where one could wish to stay.

We did our duties promptly;

There one purpose swayed the mind.

We tarried not nor lingered long

On what we left behind.

The torture of that icy seat

Would made a Spartan sob,

For needs must scrape the gooseflesh

With a lacerating cob.

That from a frost-encrusted nail

Was suspended by a string –

My father was a frugal man

And wasted not a thing.

When grandpa had to “go out back”

And make his morning call,

We’d bundled up the dear old man

With a muffler and a shawl.

I knew the hole on which he sat

’Twas padded all around,

And once I dared to sit there;

’Twas all too wide, I found.

My loins were all too little

And I jack-knifed there to stay;

They had to come and get me out

Or I’d have passed away.

In the early 1800s, John Howard Payne wrote a poem, which was set to music as a song that expressed the way Americans felt about their homes. During the dark days of the Civil War, when men were forced to leave their homes behind, the song was sung around both Northern and Southern campfires. President Lincoln and his wife claimed it as one of their favorite songs. Women embroidered its words on samplers and hung them in their parlors.

Today, its words are still familiar to us. Our homes have changed somewhat since the nineteenth century, but we still agree with the song’s sentiments—there’s just no place like home!

’Mid pleasures and palaces though we may roam,

Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home;

A charm from the sky seems to hallow us there,

Which, seek through the world, is ne’er met with elsewhere.

Home, home, sweet, sweet home!

There’s no place like home, oh, there’s no place like home!